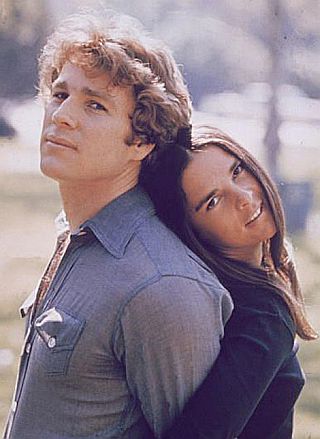

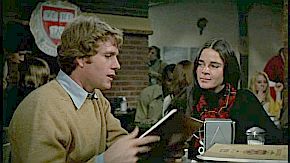

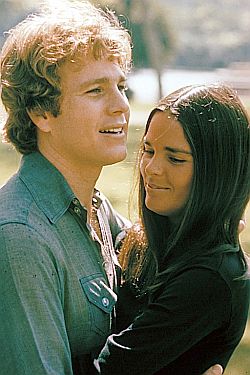

Ryan O’Neal and Ali MacGraw in 1970 studio photo: Harvard ice-hockey star & hot head meets wise-cracking Radcliffe beauty in popular novel & Hollywood film, “Love Story”. Click for film.

There, in the undergraduate idyll, these two beautiful people, full of promise and intelligence, fall in love and begin their storybook life together – or so it seems. But alas, the fates intercede in this too perfect union, providing a tragic and unhappy ending. Indeed, there are plenty of Kleenex moments in this film as the likeable and quick-witted Jenny is stricken with an unnamed cancer, eventually succumbing to the disease in a heart-wrenching hospital scene one cold winter’s night.

This story, however – rising first as a best-selling novel – became commercial gold. Though some would call it sappy by today’s standards, in the early 1970s both book and film were perfectly timed, and they permeated popular culture through and through. Millions succumbed to the Love Story spell, in print and on screen. Novel and film each made bundles of money. The story’s success marks one of those moments in popular culture when a simple love story sweeps through society as something of a gale force phenomenon, though sometimes, as in this case, to the disdain of more highbrow literary and film critics. What follows here is a recounting of the Love Story tale, novel and film, covering story recap, cultural and business impact, and some biographical follow-up on the principal players.

Erich Segal

Love Story began its journey with a somewhat unlikely creator – a Yale University classics professor named Erich Segal. Born in Brooklyn, New York, the son of a rabbi, Erich Segal studied Hebrew and other languages at an early age, becoming fluent in German, French, Latin, and Greek. He attended Brooklyn’s Midwood High School where Woody Allen was among his contemporaries.

At Harvard, Segal received a bachelor’s degree in 1958 and was both class poet and Latin salutatorian. Two more Harvard degrees followed: a master’s in classics in 1959 and a Ph.D in comparative literature in 1965.

Erich Segal became a scholar of Greek and Latin literature, publishing books on the Greek writer Euripides and the Roman playwright Plautus before writing Love Story.

Outside of his scholarship, Segal was also something of a long-distance runner. He first ran the Boston Marathon in 1955, and once finished in a respectable time of 2:56:30. By the 1960s, he was still running ten miles a day.

Professor Erich Segal, 1970s.

In the 1960s he became involved with screen writing. In fact, by 1967, he wrote the screenplay – adapted from a story by Lee Minoff – for the Beatles’ hit 1968 animated film, Yellow Submarine. He also collaborated on other screenplays through the late 1960s.

One of Segal’s own screenplays was about a romance between a Harvard University student and a Radcliffe College co-ed. Yet this story initially went nowhere. A William Morris literary agent, Lois Wallace, suggested to Segal that he turn the love story script into a novel – the novel that became Love Story.

Segal’s story was sold to Harper & Row publishers in New York, and it became a best-selling hardback in early 1970. It was quickly followed by a paperback, which by then was also being used to tout the forthcoming Paramount film which had been in production even before the hardback was issued. The film came out in mid-December 1970. More on Segal and the marketing of both book and film a bit later. First, an overview of the story, aided here by book-and-film storyline, plus screen shots from the film.

The Story

Nerdy librarian aide, Jenny Cavilleri, meets Harvard jock, “Ollie” Barrett IV in the Radcliffe library. |

Jenny succeeds in getting Ollie to take her for coffee. |

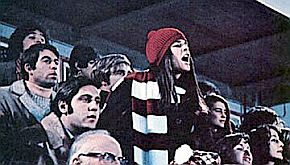

Love Story: Jenny Cavilleri at Harvard ice hockey game, cheering on new found friend, Ollie Barrett. |

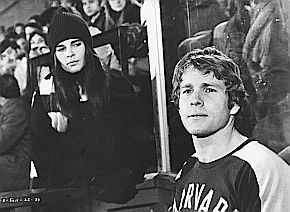

Jenny, inquiring about Ollie’s stay in the penalty box. |

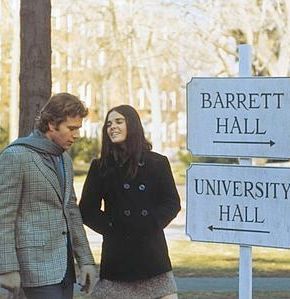

Ollie & Jenny on campus at Barrett Hall sign. |

Jenny & Ollie in more intense conversation. |

Ollie & Jenny becoming better acquainted. |

"Love Story" snow scene with Jenny & Ollie. |

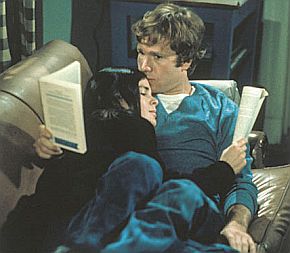

Love Story: Ollie & Jenny studying. |

Ollie & Jenny on the road to meet Ollie’s folks. |

Jenny Cavilleri meeting Oliver Barrett (Ray Milland). |

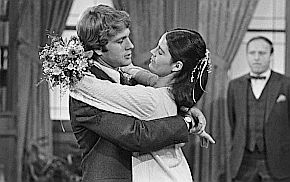

Despite his father’s disapproval, Ollie marries Jenny anyway. |

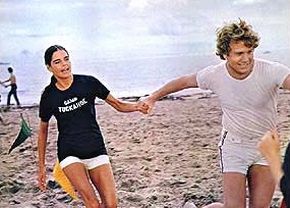

Ollie meets Jenny at her kids beach camp. |

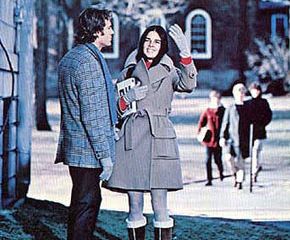

Ollie & Jenny talking at Jen's school. |

Love Story 1970: Jenny Cavilleri & her dad “Phil,” played by John Marley, attending Ollie’s graduation. |

Jenny congratulating her husband on his law degree. |

Ollie & Jenny facing Jen's prognosis. |

At Central Park skating rink cafe after their outing, |

Ollie & Jen crossing snow-covered park to hospital. |

Final screen shot of “Love Story” with a grieving Ollie (tiny figure just below “y”) staring into the deserted ice rink, where the story began with Ollie’s flashback. |

The featured romance in Love Story is that between Jenny Cavilleri, music major at Radcliffe College and Harvard ice hockey jock, Oliver “Ollie” Barrett, IV. It all begins in the Radcliffe library. That’s where the two first meet. Jenny works there to help pay her college tuition. Ollie Barrett has come to that library rather than Harvard’s because it’s quieter there and easier to find books. Ollie is a somewhat cocky kid who comes from a wealthy, old line, upper crust New England family – a well-respected family with its own history of Harvard alumni. Jenny is the only child of a widowed baker – a working-class Dad whom she calls “Phil”.

At the outset of the film Jenny appears somewhat nerdy and very much into her music. It’s Bach and Beethoven for her, music which is heard in the film’s score. And as we learn from the narrator’s opening line, Jenny also loves the Beatles.

The story is introduced in flashback mode by Ollie, who is shown in the film’s opening scene seated on a bench staring into a deserted New York city Central Park ice skating rink in a wintry, snow-covered setting. This scene comes full circle as the film’s closing sequence (more on this later).

Back at the Radcliffe library, meanwhile, it’s Jenny who makes the first move, displaying her snappy repartee with Ollie, who she labels “preppie” from the start. Ollie is on the hunt for a book he needs for an upcoming history exam, so he heads over to the reserve desk to inquire about the book. He opts for one of the two girls working there – the “bespectacled mouse type,” as he describes her – “Minnie Four-Eyes.” Here’s their exchange:

Ollie: “Do you have The Waning of the Middle Ages!”

Jenny: “Do you have your own library?” she asked.

Ollie: “Listen, Harvard is allowed to use the Radcliffe library.”

Jenny: “I’m not talking legality, Preppie, I’m talking ethics. You guys have five million books. We have a few lousy thousand.”

Ollie: [ to himself. Christ, a superior-being type! The kind who think since the ratio of Radcliffe to Harvard is five to one, the girls must be five times as smart. I normally cut these types to ribbons, but just then I badly needed that goddamn book.]

Ollie: “Listen, I need that goddamn book.”

Jenny: “Wouldja please watch your profanity, Preppie?”

Ollie: “What makes you so sure I went to prep school?”

Jenny: “You look stupid and rich,” she said, removing her glasses.

Ollie: “You’re wrong,” I protested. “I’m actually smart and poor.”

Jenny: “Oh, no, Preppie. I’m smart and poor.”

Ollie: [ in narration: She was staring straight at me. Her eyes were brown. Okay, maybe I look rich, but I wouldn’t let some ‘Cliffie—even one with pretty eyes—call me dumb.]

Ollie: “What the hell makes you so smart?”

Jenny: “I wouldn’t go for coffee with you.”

Ollie: “Listen—I wouldn’t ask you.”

Jenny: “That is what makes you stupid.”

Ollie does take her for coffee, where the two continue their sharp repartee with Ollie becoming frustrated with her barbs and the fact, that apparently, she does not know that he, Ollie, is “big-man-on-campus” Harvard ice hockey star.

Ollie: “Hey, don’t you know who I am?”

Jenny: “Yeah,” she answered with kind of disdain. “You’re the guy that owns Barrett Hall.”

Ollie: “I don’t own Barrett Hall. My great-grandfather happened to give it to Harvard.”

Jenny: “So his not-so-great grandson would be sure to get in!”

Ollie: “Jenny, if you’re so convinced I’m a loser, why did you bulldoze me into buying you coffee?” [ She looked me straight into the eyes and smiled.]

Jenny: “I like your body.”

After their initial get together over coffee, they soon begin their romance on the Harvard campus, she attending his hockey games, the two studying together, frolicking in the snow, and later, consummating their love.

In one scene they are walking across the Harvard campus, by then deep into their emotional tangle, taking measure of each other. They are talking about their relationship. Ollie has been more forthcoming at that point than Jenny, and he unloads on her for her smart-ass style:

Ollie: “Look, Cavilleri, I know your game, and I’m tired of playing it. You are the supreme Radcliffe smart-ass – the best – you can put down anything in pants. But verbal volleyball is not my idea of a relationship. And if that’s what you think it’s all about, why don’t you just go back to your music wonks, and good luck. See, I think you’re scared. You put up a big glass wall to keep from getting hurt. But it also keeps you from getting touched. It’s a risk, isn’t it, Jenny? At least I had the guts to admit what I felt. Someday, you’re gonna have to come up with the courage to admit you care.”

In that scene, they stop walking as she quietly replies, “I care,” leading to a kiss, then cut to Ollie’s dorm room and the couple making love. Shortly later in the film, in a wintry montage, they end up playing in the snow, throwing snowballs and tossing a football at each other, and wrestling in the snow together.

After several months together, Jenny tells Oliver that she has received a scholarship to study music in Paris the next year. Ollie, afraid of losing her, decides to propose marriage. Jenny after some thought, accepts the offer, and soon the couple is off to “meet the parents” — first, his.

Meet The Parents

On the drive to the Barrett family place, Jenny is somewhat taken aback as they approach the estate, with its giant mansion and extensive grounds. It is then she begins to realize just how truly wealthy the Barretts are.

The family gathering to meet the bride-to-be becomes a tense affair, as Ollie’s father does not react well to Jenny’s background. Father and son, already in a testy relationship, come to the brink when Ollie’s father tells him he will be disinherited if he marries Jenny.

The drive back to campus is not a happy one. Ollie later meets his father for dinner to try again, but this also ends badly as Ollie loses his temper. Ties between father and son from that point on are pretty much severed.

Jenny and Ollie continue to plan their wedding, traveling to Providence, Rhode Island to receive the blessing of Jenny’s Dad, “Phil.” Here too, they upset tradition, informing Phil they are not planning a traditional ceremony, with church and God. Phil is not entirely pleased, but he’s on their side in any case.

Upon graduation, Oillie and Jenny marry against the wishes of Ollie’s father. Ollie then plans to enter law school, while Jenny goes to work as a teacher. The couple struggles to pay Ollie’s way through Harvard Law School. They rent the top floor of a house near the law school. Ollie had applied for financial aid, but his Barrett Hall fame and family wealth disqualified him.

“Love Means…”

Along the way and in their marriage, the new couple have a few spats here and there, one coming after Ollie refuses to attend his father’s 60th birthday party. Jenny has been trying to move Ollie to speak to his father, but after Ollie explodes, she leaves their apartment in tears. Guilt getting the best of him, Ollie searches the Harvard campus for Jenny, visiting the all the music rooms and other places she might be. Then, having arrived back home, he finds her sobbing on their outside porch steps in the cold without her keys. As Ollie moves to apologize, Jenny stops him, delivering one of the film’s classic (and now much-parodied) lines: “Love means never having to say you’re sorry.”

Things get patched up, of course, and life goes on. Scenes of beach visits and boating flash by, and another in winter of Ollie selling Christmas trees on a city lot. Jenny and “Phil,” meanwhile, do what they can to bring the Barrett father and son back together, but the Barrett men remain at war. Ollie soon finishes his stint at Harvard Law, graduating third in his class. Phil and Jenny attend the ceremony, and life for the young couple begins to change.

Now a Harvard lawyer, Ollie takes a position at a respectable New York law firm, though one with at least part of its practice in civil liberties. The couple move to New York, and begin to plan for a family. The two twenty-somethings try to have a child, but fail. Jenny then has a series of tests.

Devastating News

One day, Ollie is called in to see Jenny’s doctor, who tells him that Jenny is dying. The tests have revealed that Jenny has a serious and deadly disease, assumed to be some kind of leukemia, though never stated. Jenny does not have long to live. Ollie is devastated, and is shown in the film taking a long and dazed walk through the city on his way home.

Reaching their apartment, he tries to act normal as he is greeted by an upbeat Jenny. Ollie tries to hide the truth from Jenny, attempting a normal life. At one point he buys two airline tickets to Paris to surprise Jenny. But Jenny soon discovers the truth about her disease, and has suspected for some time.

Somber and intimate scenes follow as the couple tries to deal with Jenny’s prognosis. She insists that he will be a “merry widower” and makes him promise that he will carry on in good form. As the disease weakens Jenny, the couple tries to spend some happy time together.

Central Park

At one point they have a brief outing in Central Park and stop at an outdoor public skating rink, where Ollie skates with the crowd as Jenny watches approvingly from the bleachers. After Ollie’s skating they stop briefly at a café near the rink where Jenny makes it known its time to go to the hospital.

From the outdoor café they make their way slowly to the hospital across the park in the snow. A weakened Jenny moves with halting steps in Ollie’s arms as they go. The Love Story piano theme rises in the background as the camera pulls back high above the couple, slowly trekking through the snowy, winter scene — a season once of happier and playful times for the couple on the Harvard quad.

Music Player

“Love Story Theme”-Francis Lai

With Jenny now in the hospital, Ollie makes a trip to Boston to see his father, asking him for $5,000 — money he needs to cover Jenny’s therapies. Ollie lies to his father saying he needs money for an affair which has led to a pregnancy. The father has no idea that Jenny is ill and in the hospital. Father and son still have their differences, but Ollie thanks his Dad for the check and heads back to New York.

Hospital Scenes

In a near-the-end deathbed scene at Mount Sinai Hospital, Jenny tells Ollie her illness “doesn’t hurt,” describing it “like falling off a cliff in slow-motion.” Jenny sees that Ollie is pained and tries to buck him up in her trademark sassy manner – “stop blaming yourself, you god-damn stupid preppie. It’s nobody’s fault. It’s not your fault… That’s the only thing I’m gonna ask you…”

Jenny also assures him that he really didn’t “take away” her trip to Paris or her music career — “and all that stuff you thought you stole from me….” But she does insist that he quit blaming himself or leave her bedside. She then asks him to hold her, beside her in bed, which he does. Jenny then slips away.

Afterwards in the hallway, Ollie speaks with Jenny’s father Phil briefly then leaves the hospital in a daze. On his way out, he meets his own father who has rushed down from Boston, learning the real reason why his son had asked him for money. “Why didn’t you tell me?,” says the father. “…I want to help.” Ollie simply replies: “Jenny’s dead.” His father begins to offer his condolences, saying “I’m sorry…,” at which point Ollie interrupts him, with tears in his eyes, quoting Jenny’s famous line: “Love means never having to say you’re sorry.” It is the last line of dialogue in the film.

As a devastated Ollie walks across the street to a snow-covered Central Park, the camera slowly pans out for a few minutes as the “Love Story” piano theme plays in the background. Ollie is left sitting on a bench staring into the ice rink contemplating life without Jenny as the story comes full circle back to the scene where the film began.

Love Story, however, also has an interesting publishing and box office history, as well as the twists and turns that befell its principle stars and creator, some of which follow below. First, the book.

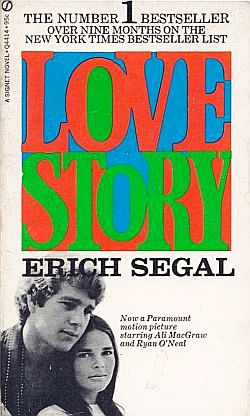

A paperback version of “Love Story,” with Ryan O’Neal & Ali MacGraw on the cover, was used to promote the film in 1970-71. Click for copy.

The Book

Love Story was first serialized in the Ladies Home Journal magazine in February of 1970. About the same time, Harper & Row published the book in a slim 131-page hardback edition, releasing it for sale on February 14, 1970, Valentine’s Day.

According to Mel Zerman, a former Harper & Row executive who was interviewed in 2006 for The American Legends website, “Harper didn’t realize exactly what they had.” The first printing was going to be in the low-to-normal range of 5,000-to-7,500 copies, which in retrospect, Zerman said, “was laughable.” Harper later bumped up the print run to 57,000 hardbacks. But even that wasn’t enough. Television soon helped create a giant demand for the book. According to Zerman:

“…The book burst on the scene one morning when Barbara Walters, who was a TV hostess, began her program by saying: ‘I was up most of the night reading a book I couldn’t put down, and when I finished it, I was sobbing. I cried and cried.’ That’s all the women of America had to hear. By the time bookstores were opening all over the United States they were getting calls for a book called Love Story by someone you never heard of named Erich Segal. Harper went crazy. We were out of stock within hours….”

By mid-May 1970, Love Story was No. 1 on the New York Times bestsellers list and by early 1971 there were 1 million hardbacks in print. A paperback edition came out in 1970 too, with more than 4.3 million copies printed by mid-November 1970, then the largest print order in publishing history. These copies sold so well that within a week another 600,000 were printed. A month after the paperback was released, the hardbacks were still selling at 2,000 copies a week. One 1971 Gallup poll found that Love Story was read by one out of every five Americans; it would eventually sell more than 21 million copies. Erich Segal would later say that he set out to make people cry with the book, adding that if he could get women to cry, he knew it would be a commercial success. As a New York Times No. 1 best- seller for most of 1970, Love Story became the year’s top-selling work of fiction in the U.S.

Then came the film, released by Paramount on December 16th, 1970, as the book was still being widely read. The film had the effect of selling more books and keeping Love Story on the bestsellers list. According to one 1971 Gallup poll, the book was read by one out of every five Americans. Love Story would eventually sell more than 21 million copies and was translated into more than 20 languages worldwide. But not everyone was smitten by Love Story, especially literary critics. When the book was up for the 1971 National Book Award, some judges threatened to resign from the award process unless Love Story was withdrawn from nomination. “It is a banal book which simply doesn’t qualify as literature,” said novelist William Styron, the head judge of the fiction panel. “Simply by being on the list it would have demeaned the other books.” So, Love Story was rejected.

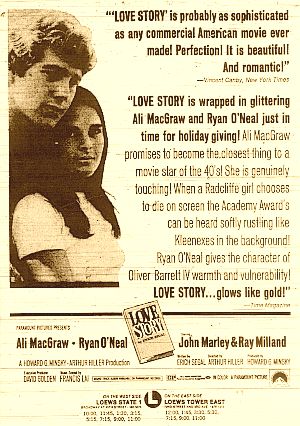

1970 newspaper ad for the 'Love Story' film features upbeat review quotes from Vincent Canby and Time magazine.

Still, in popular culture Love Story was a big hit, and it rode atop the bestseller list for more than year. In the process, Segal – already a rich man from 1968’s Yellow Submarine – was deluged with offers for movies, plays and more books. Segal told a Time magazine reporter he was no wunderkind, but had worked hard and learned from past failures.

Segal’s new-found success put the 32 year-old squarely in the celebrity firmament and he became a hot property for a time. But at the initial planning for the film – like the book’s uncertain publishing prospects – there were only modest expectations.

The Film

Segal’s screenplay, in fact, had been turned down by every studio in Hollywood. However, his agent, Howard Minsky of the William Morris agency, had faith in the story and really went to bat for Segal, convincing Paramount to take a chance on it. Segal also had another supporter in his corner: Ali MacGraw. She was a friend of Segal’s and was also then the wife of Paramount executive vice president, Robert Evans.

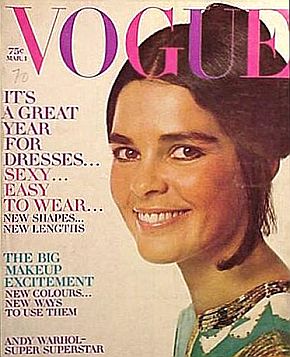

It was MacGraw who had discovered the Love Story screenplay, and even though several studios had turned it down, Evans agreed to produce it for his wife, casting her in the role as leading lady. Evans thought the story might prove to be a small profitable film that might just buck the rough sex-and-violence trend then prominent in film.

Still, there was no expectation the film would be a blockbuster hit. In later interviews, Arthur Hiller, the film’s director, also acknowledged that the film was not originally conceived as a high-profile property. It had a limited budget, and the producers had to use a number of existing locations as sets to save money. One early problem that confronted the film’s producers was finding the male lead to play Ollie. Initially, Ryan O’Neal had turned down the role, as did Robert Redford, Michael York, and Beau Bridges. At its film debut, Love Story received glowing reviews and set movie- house records all over the country. Eventually, O’Neal agreed to take the part. Other actors in the film included Ray Milland, who played O’Neal’s father, and John Marley, Jenny’s father. To prepare for their roles, O’Neal learned to ice skate and MacGraw took harpsichord lessons.

When the film was released on December 16, 1970, it wasn’t known exactly what would follow. The best-selling book had certainly set the stage. And as it turned out, there was little to worry about. The reviews that came in right before Christmas that year were quite flattering and enthusiastic. “Love Story is probably as sophisticated as any commercial American movie ever made!,” wrote Vincent Canby of The New York Times. “Perfection! It is beautiful! And romantic!” Time magazine’s review was a big booster, too:

“Love Story is wrapped in glittering Ali MacGraw and Ryan O’Neal just in time for holiday giving! Ali MacGraw promises to become the closest thing to a movie star of the 40’s! She is genuinely touching! When a Radcliffe girl chooses to die on screen the Academy Awards can be heard softly rustling like ‘Kleenexes in the background!’ Ryan O’Neal gives the character of Oliver Barrett IV warmth and vulnerability! Love Story…glows like gold!”

"Love Story" photo: Ryan O'Neal & Ali MacGraw at kids camp beach scene.

One Time magazine writer in January 1971 was quite taken with Ali MacGraw, and when she explained in one interview that she wasn’t quite “hungry enough” to be a star, or even a serious actress, he wrote:

“…She doesn’t have to be hungry or an actress. She just has to stand there, and people buy tickets. The clean-boned, finishing-school face, the large, liquid eyes that cannot express doubt, the barely upholstered model’s body, the metallic purr….In two pictures, she has managed to suggest the incarnate campus heroine, full of itchy, bitchy resolve. … In short, she is the kind of girl a boy would want to take home even if his parents were there, but especially if they were not.”

Time’s writer also suggested that MacGraw’s performance in Love Story might represent a return to something basic in the U.S. cinema: “To a fresh flowering of the romance and sentimentalism of the ’30s and ’40s. To a time when pictures told a story, when you could go to the movies and take the family, when you could lose yourself in fantasy, when you got chills at the final fadeout….” Movie critic, Roger Ebert, taking on those who felt the film a little too weepy, wrote:“…I would like to consider, however, the implications of Love Story as a three-, four-or five-handkerchief movie, a movie that wants viewers to cry at the end. Is this an unworthy purpose? Does the movie become unworthy, as Newsweek thought it did, simply because it has been mechanically contrived to tell us a beautiful, tragic tale? I don’t think so. There’s nothing contemptible about being moved to joy by a musical, to terror by a thriller, to excitement by a Western. Why shouldn’t we get a little misty during a story about young lovers separated by death?”

Love Story won an Oscar for best music and was nominated in six other categories. At the Golden Globe ceremony it took five awards, including Best Picture (drama), Best Director, and Best Screenplay for Segal. At the box office, the film grossed more than $48 million (roughly $263 million in today’s dollars)Love Story out-grossed other popular films that year, among them, Patton, MASH, Catch 22 and Woodstock.. Of U.S. film’s released in 1970, Love Story was No. 1 at the box office, out-grossing other films that year including: Airport (No. 2) with Burt Lancaster; MASH (No. 3) with Donald Sutherland and Eliott Gould; Patton (No. 4) with George C. Scott; Little Big Man (No. 7 ) with Dustin Hoffman and Faye Dunaway; Ryan’s Daughter (No. 8 ) with Robert Mitchum; and Catch 22 (No. 10) with Alan Arkin. Love Story’s gross was three times that of Warner Brothers’ Woodstock (No. 6), a popular film on the famous 1969 rock concert. At the Academy Awards that year, Patton won Best Picture and George C. Scott, Best Actor. Glenda Jackson won Best Actress for her role in Women in Love. Paramount studios, meanwhile, then on the brink financially, was “saved” by Love Story’s very profitable box office, enabling the studio to live another day and turn out several other winners that decade, including Chinatown, The Godfather, and others.

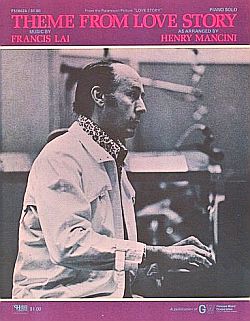

Love Story Music

Cover of sheet music for Francis Lai's piano version of the "Theme From Love Story," with photo of Henry Mancini. Click for Lai's soundtrack.

The Love Story soundtrack album also did well, and spent six weeks at No. 2 on the Billboard album chart. One of the tracks on the album, “Skating in Central Park,” which plays over a sequence of MacGraw and O’Neal romping in the snow and ice skating, was written by John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet. In fact, the Love Story soundtrack orchestra featured several jazz notables, including Milt Jackson (vibraphone), Percy Heath (bass), Connie Kay (drums), Bill Evans (piano) and Jim Hall (guitar).

Francis Lai’s simple melody for the Love Story piano theme, however, did not have lyrics, which was soon remedied after Carl Sigman, a lyricist, penned words for the song. That theme then became “Where Do I Begin?,” and with singer Andy Williams, the Love Story song took on a second life, as his version rose on the popular charts for several weeks in early 1971 – peaking at No. 9 on the Hot 100 and No. 1 on the Easy Listening chart. Since then, countless others have recorded cover versions of the song. Henry Mancini also had an instrumental version that did well on the music charts. For a time, in the wake of the film, the song seemed to be everywhere.

Erich Segal, shown speaking at a 1980 news conference in West Germany. Photo: AP/ M. Langsdorff.

Success & Loss

Professor Erich Segal, meanwhile, at the height of the Love Story run, continued to be well-received on the celebrity circuit. At one point, he appeared on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson four times in a single month. He also appeared on the Today Show and the Dick Cavett Show.

In the film world, he became a judge at the Cannes Film Festival. Segal, in fact, was making weekend trips to Paris and London while continuing to teach at Yale. His course there became quite popular, filling a 600-seat auditorium. “I’m kind of a folk hero there,” he told the Washington Post at one point in 1970 “– the closest thing they have to a Beatle.”

Segal also took a job as an ABC-TV commentator for the 1972 Olympic Games, using both his personal experience as a runner and his classical knowledge of ancient Greece in the broadcast booth. Back at Yale, however, his academic peers were not amused (or were jealous), and despite his scholarly publications and his doctorate earned at Harvard, Yale denied him tenure in 1972.

By about 1973, Segal and Love Story had receded into the cultural background. However, he would continue to receive mention in the press when he published his subsequent work.Segal had followed up after Love Story with other novels, including Jennifer on My Mind in 1971 and Fairy Tale in 1973. But it wasn’t until Oliver’s Story of 1977 — billed as “the book that begins where Love Story ends”– that another movie was attempted the following year. That film cast Ryan O’Neal as the struggling widower who meets a new lady, Candice Bergen. Although the book, Oliver’s Story made it to the bestsellers list, neither it nor the movie by the same name repeated the success of Love Story. In fact, many regarded the film as a flop.

Segal, meanwhile, continued writing through the 1980s and early 1990s, turning out more titles, among them: Man, Woman and Child (1980), A Change of Seasons (1981), The Class (1985), Doctors (1988), and Acts of Faith (1992).

Around the time of Segal’s publication of The Class in 1985, he was still being asked about Love Story, the harsh views of some critics, and that he lost tenure at Yale over it. “But am I really sorry I wrote ‘Love Story’?, he offered in reply to similar questions at People Weekly, “Bullshit. I’m overjoyed I did.” And many readers found his subsequent books to be quite good – a number of which also became bestsellers.

When the body of his popular works is looked at as a group, Segal is seen, in some ways, as the patriarch of a particular genre, which some call “bereavement fiction,” similar in content to contemporary novelists such as Nicholas Sparks, though Segal’s work is regarded as somewhat weightier.

In the 1980s Segal contracted Parkinson’s disease. He died of a heart attack in January 2010. He was 72 year old.

|

“Al, Tipper & Tommy Lee”  Al & Tipper Gore, wedding day, May 19, 1970, National Cathedral, Washington, D.C.  Tommy Lee Jones made his film debut in "Love Story" in a brief role.  Al & Tipper Gore, circa 1980s. In 1970, Segal said that the novel’s basic story came from one of his students, whose wife had died, and that the model for Jenny was a woman Segal had dated in his own student days at Harvard. And in fact, that part of the story surfaced in 1997 as well, when a woman named Janet Sussman told Maureen Dowd of the New York Times that she was the real life model for Jenny, and that Segal had written her love letters for years. Sussman also told her story to Oprah Winfrey in 2010. Segal’s daughter, Francesca Segal, later noted on an Amazon.com page for a 50th anniversary edition of Love Story, that when Segal first set out to write the story, he had learned that a former student of his from Harvard had lost his wife to cancer at age twenty-five. “My father, a few years older and still grieving the death of his own father, was consumed by the story.” |

O’Neal & MacGraw

Given the notices Ryan O’Neal and Ali MacGraw received in the aftermath of Love Story, there were great expectations for their respective careers. And O’Neal and MacGraw both had their successes, to be sure. In 1972, O’Neal starred with Barbra Streisand in the comedy, What’s Up, Doc? and in 1973 alongside his Oscar-winning ten-year old daughter, Tatum, in Paper Moon.In 1973, Ryan O’Neal was ranked No. 2 in the annual Top Ten Box Office Stars list, behind Clint Eastwood that year. Other subsequent films for O’Neal, included: Nickelodeon (1976, also with Tatum), Barry Lyndon (1975), A Bridge Too Far (1977), Oliver’s Story (1978), The Driver (1978), and Irreconcilable Differences (1984).

Twice previously married and divorced, O’Neal had a long-term on-and-off relationship with actress Farrah Fawcett until her death in June 2009. O’Neal had been diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia in 2001, which as of 2006, was in remission.

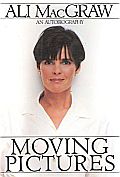

Ali MacGraw, before Love Story, had gained notice for her role as Radcliffe student Brenda Patimkin in the 1969 film Goodbye, Columbus. That year, she also married Paramount exec Robert Evans in 1969, who was something of a Hollywood wunderkind, having risen to head paramount in 1966 at the age of 34. In 1972, MacGraw co-starred in the action adventure film The Getaway with Steve McQueen, whom she married in 1973. She turned down subsequent film roles after promising McQueen that she would help take care of him during his “semi-retirement.” However, she and McQueen divorced in 1978. She then returned to film, appearing in Convoy (1978), Players (1979), and Just Tell Me What You Want (1980). In 1983 she appeared in television miniseries China Rose and The Winds of War, the latter with Robert Mitchum. Then came her role as Lady Ashley Mitchell in the prime-time ABC-TV soap opera hit Dynasty in 1984-85. In 1991, People magazine chose her as one of the “50 Most Beautiful People” in the World. MacGraw’s 1991 autobiography, Moving Pictures, revealed her struggles with alcohol and men. In her fifties, she became a Yoga devotee and in 1994 produced the video – Ali MacGraw Yoga, Mind and Body, which became a bestseller, credited with influencing yoga’s U.S. popularity in the 2000s.In October 2010, Oprah Winfrey arranged a “Love Story Reunion” on her popular TV show, marking the 40th anniversary of the film, reuniting MacGraw and O’Neal. On the show, the two discussed their roles in the movie and O’Neal admitted he had a crush on MacGraw throughout the film’s production, asking her to go away with him at one point even though both were then married. O’Neal and daughter Tatum also appeared in a 2011 Oprah Winfrey Network TV reality show.

Postscript

Love Story today, both book and film, are often parodied and seen as dated and sappy. Even in 1970-71, critics found weaknesses in the story and its context. There was little mention of politics or the concerns of the day in the storyline, which some found lacking, especially at a place like Harvard. As one blogger put it:

The title page for the 1970 book, "Love Story."

“…There’s no urban grit, no Nixonian paranoia, no disillusionment, no radical politics. No politics at all, actually! There are oblique references to the feminism and “the troops,” but it all happens in a fairly timeless vacuum, where the characters are totally unaffected by the tumult of the 1960s. Harvard was, like many American schools, a hotbed of radicalism and antiwar activity; there was a student strike in 1969 on campus when the movie was being filmed, and yet you’d never know such radicalism was afoot in these snowy, photogenic environs….”

In the late 1960s and early 1970s the U.S. was at war in Vietnam and the country was divided. Social values were being challenged at every turn. The country in late 1970 was less than two years removed from the tumultuous events of 1968, including the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy, and the bloody Democratic national presidential convention in Chicago.

But at the time, there was also a kind of “moral exhaustion” setting in; a bit of retreat from all the chaos and upheaval that had transpired; a lull on campus, if only temporary, and a turning inward, toward the personal. The popularity of heavy, social-awareness type books seemed to have slowed around that time as well. “I think black study books and women’s lib books have shot their wad,” remarked one Simon & Schuster advertising director to a Time magazine reporter in January 1971. “The kids want romance. They’re discovering again that going to college is a wonderful little world….”

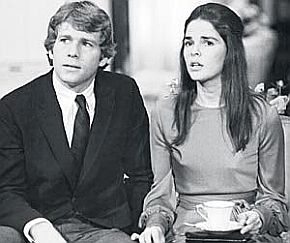

Ryan O’Neal & Ali MacGraw in “Love Story” photo, 1970.

Love Story, of course, never really promised politics or social context, or actually any depth beyond its central theme. Love Story was just what its title said it was, nothing more. And the public ate it up. “I think people were ready for it,” explained Love Story director Arthur Hiller in a 2001 interview looking back on that time. “Many moviegoers wanted a respite from the [rough] type of films… A change of pace. Love Story was just what the title indicated, just what we promised; Erich [Segal] called it ‘an affirmation of the human spirit.’ He was right, and at that particular moment in time we were all looking for that affirmation.”

In the U.K., “Love Story” made a run as a stage play in 2010.

Still, to this day, Love Story remains a popular film, at least in memory. As of June 2002, it was ranked No. 9 on the American Film Institute’s 100 greatest love stories in American cinema. Love Story also remains one of the most successful films in Hollywood history, among the top 40 in adjusted box office gross.

For a somewhat similar story at this website see, “Of Bridges & Lovers,” an account of the 1992 book and 1995 film, Bridges of Madison County. See also at this website, “Doctor Zhivago,” a detailed review of the classic, award-winning 1965 Hollywood film starring Omar Sharif and Julie Christie. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 29 June 2011

Last Update: 9 December 2023

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “The Love Story Saga, 1970-1977,”

PopHistoryDig.com, June 29, 2011.

____________________________________

Other Film Choices at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Love Story: Ollie Barrett & Jenny Cavilleri on campus. |

Jenny Cavilleri & Ollie Barrett in "Love Story." |

Ollie & Jenny arriving at the Barrett estate to “meet the parents.” |

Love Story: meeting the parents not going well. |

Ollie & Jenny beginning marriage ceremony. |

Love Story: Jenny & Ollie, beach camp scene photo. |

Love Story: Ollie taking break from Central Park ice skating, looking up at Jenny, sitting in bleachers. |

Jenny watching Ollie skate in Central Park from bleachers, shortly before they walk to the hospital. |

Ali MacGraw, Vogue cover girl, March 1970. |

“All This and Terence Too,” Time, May 18, 1970.

Vincent Canby, “Love Story (1970) – Screen: Perfection and a ‘Love Story’: Erich Segal’s Romantic Tale Begins Run,” New York Times, December 18, 1970.

Charles Champlin, ‘Love Story’ Tells It Like It Always Was,” Los Angeles Times, December 20, 1970, p. M-1.

Robert McG. Thomas, Jr., “Love (and Success) Story,” New York Times, December 20, 1970.

“Love Story,” New York Times, December 21, 1970, p. 51.

Erich Segal, Love Story, New York: Harper & Row, 1970.

Gary Arnold, “‘Love Story’,” Washington Post/ Times Herald, December 26, 1970, p. B-1.

Richard Corliss, “Who Says All the World Loves a ‘Love Story’?,” New York Times, January 10, 1971, p. D-11.

“Ali MacGraw: A Return to Basics,” Time (cover photo & story), Monday, January 11, 1971.

Henry Raymont, “Book Unit Rejects ‘Love Story’,” New York Times, January 22, 1971, p. 16.

“‘Not Literature’: ‘Love Story’ Bounced From Fiction Contest,” Los Angeles Times, January 23, 1971, p. A-12.

“Banal ‘Love Story’,” Washington Post/ Times Herald, January 25, 1971, p. D-7.

Wayne Warga, “‘Love Story’ Gets Seven,” Los Angeles Times, February 23, 1971, p. A-3.

Associated Press, “‘Airport,’ ‘Patton’ Top Oscar Entries, Win 10 Nominations Each; ‘Love Story’ Garners 7,” New York Times, February 23, 1971.

“Segal the Scholar,” Time, Monday, March 15, 1971.

Wayne Warga, “Why He’s in Love With ‘Love Story’,” Los Angeles Times, March 28, 1971, p. N-1.

Neil Amdur, “Erich Segal and the Boston Marathon: ‘Love Story’ of a Long-Distance Runner,” New York Times, April 4, 1971.

“‘Love Story’ Criticized; Vatican Weekly Criticizes Both Book and Film Versions…,” New York Times, April 22, 1971.

“Erich Segal Is on Riviera As Juror at Film Festival,” New York Times, May 8, 1971.

Cynthia Grenier, “Erich Segal, at Cannes, Links Press to Departure From Yale,” New York Times May 22, 1971.

“Erich Segal’s Identity Crisis,” New York Times, June 13, 1971.

Martin Arnold, “Erich Segal Denied Tenure as Yale Professor,” New York Times, April 12, 1972.

Charles T Powers, ” ‘Love Story’ Letdown; Erich Segal Untracked,” Los Angeles Times, April 11, 1973, p. H-1.

“Segal Resigns From Yale,” New York Times, November 5, 1973.

“Erich Segal,” Wikipedia.org.

“Love Story (novel),” Wikipedia.org.

Tim Dirks, “Love Story,” FilmSite.org.

“Love Story,” TCM.com.

“Love Story (film),” Wikipedia.org.

Melinda Henneberger, “Author of ‘Love Story’ Disputes a Gore Story,” New York Times, December 14, 1997.

“Gore Apologizes for Confusion Over ‘Love Story’,” Los Angeles Times, December 15, 1997, p. 31.

Maureen Dowd, “Liberties; Is Janet Jenny?,” New York Times, December 17, 1997.

“Meet the Real Jenny From Love Story”(video), Oprah.com, October 12, 2010.

Michael Kelly, “The Artful Dodger and the Good Son,” Washington Post, December 17, 1997, p. A-25.

Daniel S. Fettinger and Lisa Warner, “Film Rewind: Revisiting Love Story,” June 18, 2005

Roger Ebert, Movie Glossary, “Ali MacGraw’s Disease.” Movie illness in which the only symptom is that the sufferer grows more beautiful as death approaches. (This disease claimed many screen victims, often including Greta Garbo),” RogerEbert. SunTimes.com.

“Arthur Hiller, Artist Interview: Recalls the Inauspicious Beginnings of His Moment-Defining Love Story,” BarnesAndNoble.com, April 17, 2001.

“Behind the Scenes: Mel Zerman on The Marketing of Erich Segal’s Love Story,” American Legends.com.

“Ali MacGraw,” Wikipedia.org.

“Ryan O’Neal,” Wikipedia.org.

Meryl Gordon, “A Long-Lost Love: Ali MacGraw Comes out of Hiding to Appear on Broadway for the First Time,” New York Magazine, March 26, 2006.

Ty Burr, “Reel Boston,” Boston Globe, February 27, 2005.

Andy Sturdevant, “Love Story 1970, Grit-Free: 70s Cinema Without The 70s,” Tumblr.com.

Nick Owchar, Jacket Copy, “‘Love Story’ Author Erich Segal Dies at 72,” Los Angles Times, January 19, 2010.

James K. McAuley, ” ‘Love Story’ Author Erich Segal Dies at 72,” The Harvard Crimson, Wednesday, January 20, 2010.

Margalit Fox, “Erich Segal, ‘Love Story’ Author, Dies at 72,” New York Times, January 20, 2010.

Brian McCoy, “Forty Years Later, Recalling the Hidden Jazz of ‘Love Story’,” Examiner.com, December 14th, 2010.

Lou Lumenick, “Still in ‘Love’: 40 Years On, Here’s the True Story Behind ‘Story,” New York Post, December 16, 2010.

“Love Story (1970) – Official Trailer,” You Tube, (2:49 film synopsis along with Francis Lai piano theme).

The Kid Stays in the Picture, 1994 book and 2002 film on the life story of Hollywood producer and studio chief Robert Evans, former husband of Ali MacGraw. See Wikipedia.org.

“Love Story” as play in the U.K, 2010-2011.

Love Story @ Google Books.

Some folks still discovering the book in the 2000s; see for example: “Marginalia || Love Story, by Erich Segal,” Sasha & The Silverfish.

__________________