Doctor Zhivago is the name of a famous Russian novel and an equally famous Hollywood film based on it — an epic love story cast in a time of war and upheaval during World War I and the Russian Revolution. The novel was completed in 1957 by Noble Prize-winning Russian author and poet, Boris Pasternak. While immensely popular in the West, the politically-sensitive book was banned in the Soviet Union for decades, smuggled out of Russia in 1957 and first published in Italian, followed by English editions in 1958. It became an international best seller and is ranked among the greatest works of fiction of all time.

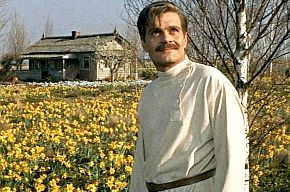

Boris Pasternak (1890-1960), in a 1958 photo at Peredelkino, Russia, where he lived southwest of Moscow. |

Pasternak and Doctor Zhivago became caught up in Cold War politics. He was announced winner of the 1958 Nobel Prize for Literature in late October 1958, but did not officially accept the award for fear of Soviet reprisals (decades later, in 1989, Pasternak’s son, Yevgeny, accepted the award on behalf of his father). Pasternak’s story, wrapped up in Cold War intrigue (including CIA doings and years of repression at home), is itself the subject of separate books, along with his interesting career, love life, and one long-standing love affair that fueled Doctor Zhivago and more. He remains lauded as a seminal Russian writer, poet and national hero. Doctor Zhivago, meanwhile, in 2003, became part of Russian school curriculum.

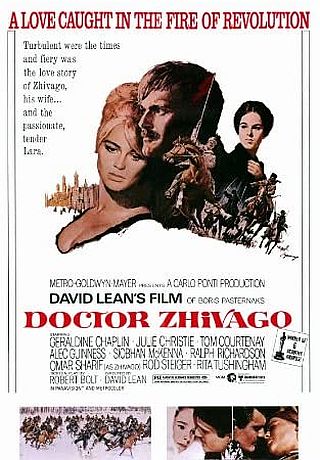

1965 film poster for Doctor Zhivago - “A Love Caught in the Fire of Revolution” – showing Zhivago with lover Lara, and over his shoulder, his wife, Tonya. Click for Amazon poster page.

The film was nominated for ten Oscars, wining in five categories: Best Screenplay, Best Original Score, Best Cinematography, Best Art Direction and Best Costume Design. Also nominated for Best Picture and Best Director, Zhivago lost out in those categories that year to The Sound of Music.

At the Golden Globe Awards, however, Zhivago took five awards, including Best Picture and Best Actor for Omar Sharif.

At its release in 1965, Doctor Zhivago became the second highest grossing film that year. And into the 2010s, when adjusted for inflation, Doctor Zhivago remains among the top grossing films of all time in the U.S. and worldwide, accounting respectively, for $1.1 billion and $2.1 billion in ticket sales. It is also ranked among the most popular and /or highest grossing films in Australia, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, and the UK.

What follows here is primarily a recounting of the film story, offered with the aid of screenshots from the film.

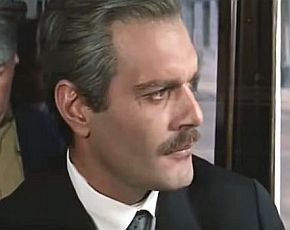

The film and story are set in Russia during 1913–1922, including a turbulent time of upheaval and change, from the period prior to World War I when Czars still ruled, and spanning the Russian Revolution of 1917 and civil war that followed when White and Red Russian partisans clashed for power. But Doctor Zhivago, at its core, is a love story told against this epic background. The politics are secondary and backdrop, though do receive a few pointed barbs here and there. The story centers on the life of surgeon-poet, Yuri Zhivago, played memorably by Omar Sharif.

Orphaned as a young boy, Yuri is raised in Moscow and becomes a doctor, though he also becomes a successful poet, which is his passion. As a young doctor, he marries Tonya (Geraldine Chaplin), an upper class girl he has known since childhood and who he dutifully loves. But as war and political upheaval begin, the life of Zhivago and his adopted family is upended. He is drafted by the Army to attend wounded soldiers at the front. In this service, he is assisted by a beautiful nurse, Lara (Julie Christie), who he has seen briefly a couple of times earlier in Moscow. More on those later.

Album cover for “Doctor Zhivago” soundtrack, showing Zhivago with wife Tonya at left, and lover Lara, at right. Click for copy.

Music Player

Doctor Zhivago Soundtrack

“Main Title” – 1965

Powerfully complimenting the film throughout is the award-winning soundtrack by Maurice Jarre (sample “Main Title” above), and the especially evocative “Lara’s Theme,” a recurring motif of possibility, longing, and reunion that is heard throughout the film, often in fragments, but signals the love and struggles of Zhivago and Lara.

David Lean’s film, meanwhile, captures much of the drama – and the expansive and humbling Russian landscape – often through the eyes of Zhivago. But at the outset, the film uses flashback framing to set the story, via Zhivago’s half-brother, Yevgraf Zhivago (Alec Guinness). Yevgraf becomes a Communist Party regular in the course of the story, but he periodically advises and helps Yuri to stay on the right side of party expectations …Poetry, you see, has fallen out of favor, among other things.

In an early scene setting up the flash back for the Zhivago story, half brother Yevgraf shows suspected daughter of Yuri and Lara a copy of Yuri’s book, “Poems for Lara.”

It is here that the movie’s central story begins as Yevgraf starts to tell the young women the tale of her father, Doctor Zhivago.

That story then opens with an expansive view of the Russian countryside, during a funeral scene, as Yuri Zhivago, then a young boy, has lost his mother. Against a backdrop of looming snow-covered mountains and an expansive plain, a distant, barely-visible crowd of people is seen, until the camera cuts to a close-up revealing a group of mourners in a funeral procession.

With the hulking backdrop of snow-covered mountains, a barely visible funeral procession (tiny black figures, lower left), makes its way across an expansive plain to a cemetery where the mother of young Yuri Zhivago will be buried.

At the cemetery, young Yuri Zhivago is holding a bouquet of blue flowers as his mother’s casket is nailed shut and lowered into the grave. A mournful Russian dirge is backing the scene, as wintry winds howl, and young Yuri Zhivago takes in the scene. It is one of the first such scenes where viewers experience Yuri’s sensitivity to the natural world, with the camera serving as Yuri’s eyes, pans to a nearby tree, its leaves whipped by the wind, suggesting the poet-in-the-boy is stirring even then.

Young Yuri Zhivago, with flowers at left, at the grave site of his mother as services are performed.

The orphaned Yuri will be taken in by friends of his mother, the Gromekos, an upper class family with a home in Moscow and a country estate near the Ural Mountains. The Gromekos have a daughter, Tonya, who is the same age as Yuri, and who he will later marry. They have all attended the funeral and will stay at the Monastery that evening.

Tonya, at left, with her parents, the Gromekos, putting Yuri to bed, still at the funeral site, before heading back to their home in Moscow where Yuri will live with them – here presenting Yuri with his mother’s balalaika.

The night of funeral, as Yuri is put to bed, he is told by Mrs. Gromyko that his mother was a very good player of the balalaika, a three-string, guitar-like Russian instrument with a triangular wooden base used in Russian folk and dance music. Yuri is given his mother’s instrument, as the sound of the balalaika is heard repeatedly throughout the film. Yuri will live with the Gromekos in Moscow.

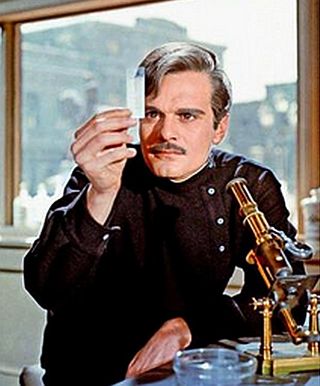

Young medical doctor, Yuri Zhivago in Moscow, examining a slide specimen at a medical bench with microscope. |

Tonya Gromeko (Geraldine Chaplin), who has grown up with Zhivago, has become a beautiful woman and will become engaged to him after schooling in Paris. |

Victor Komarovsky (Rod Steiger), a well-off aristocrat, is something of a lout, and becomes a nemesis to Lara and Zhivago. |

Lara Antipov (Julie Christie), 17, at her mother’s dress shop in Moscow. |

Early in the film, Yuri Zhivago (left), runs from his lab to catch a trolley, taking a seat behind Lara, who he has not yet met – their paths crossing anonymously, an irony emerging later. |

Upon leaving the trolley, Lara finds boyfriend Pasha passing out political leaflets, to her dismay. |

Victor’s lover, Amelia, Lara’s mother, is ill, unable to keep a dinner date with him, urging him to take Lara in her place. |

Victor Komarovsky begins his affair with young Lara after taking her out for dinner and dancing. |

The Czar’s cavalry run down and slaughter street protestors, as Zhivago happens to witness the horror from a balcony. |

Pasha, with his face sliced, has come to Lara after the protest carnage on the Moscow streets. |

Yuri Zhivago, entering the Moscow town home of the Gromekos where he grew up, meeting Anna Gromeko, who has mail for him. |

The Gromekos and Zhivago greet Tonya who has arrived in Moscow by train from Paris. |

Tonya shares rave reviews of Zhivago's poetry from Paris. |

Komarovsky, in his secret affair with Lara, dresses her in clothes of his liking, takes her dancing, and plies her with food and drink. |

Zhivago and his medical mentor, help save Lara’s mother, Amelia, after suicide attempt. |

At restaurant meeting with Victor, Pasha asserts himself as capable of marriage to Lara, while Victor does not then confront him. |

Later, at dress shop, Victor & Lara argue over Pasha, slapping each other, with Victor then forcing himself on Lara. |

Tonya and Zhivago at the Christmas party in Moscow where an announcement of their engagement is expected. |

Lara, with gun, shoots at Komarovsky during Christmas party as he is playing cards in the rear of the hall. |

Victor, rising from his card game, discovering he has been shot, but only slightly wounded. |

As Zhivago is dressing Komarovsky’s arm wound, the two have a somewhat testy exchange about Lara. |

Fast forward some years later, and Yuri is now about to become a young doctor, being urged by his mentor at medical school to pursue research. He is also a nationally recognized and published poet at this time.

In this scene, Zhivago’s medical professor engages Yuri in conversation as he is peering into a microscope, marveling at all the “pretty things” he is seeing:

Professor: “What will you do next year, Zhivago?”

Zhivago: “I thought of General Practice.”

Professor: “Well think of doing pure research. It’s exciting. Important. Can be beautiful.”

Zhivago: “General Practice.”

Professor: “Life… He wants to see life…. Well, you’ll find that pretty creatures [like those Zhivago marvels at under the microscope] do ugly things to people.”

Zhivago’s childhood companion, Tonya, is off in Paris at a private school, and has become a beautiful young woman. She is expected to return to Moscow after her schooling.

Also in Moscow is teenager Lara Antipova, daughter of dressmaker and single mother, Amelia. Lara works as a seamstress at her mother’s dress shop, where she will confront some difficult days ahead.

Her mother’s lover and business advisor is Victor Komarovsky, played by Rod Steiger. Komarovsky, a well-off aristocrat, is something of a lout, who can be ruthless in his dealings. In fact, Komarovsky has some history with the Zhivagos, it seems, having had a hand in cheating Yuri out of an inheritance.

Komarovsky also becomes interested in young Lara. More on that in a moment.

Lara’s boyfriend and future husband is “Pasha,” a young political idealist and revolutionary, played by Tom Courtenay.

Early on in the film, there is a scene that opens with Yuri Zhivago boarding a Moscow trolley and coincidentally taking a seat behind Lara, who is then unknown to him. A few stops later, as Lara moves to exit the trolley, she brushes by Zhivago.

Lara & Pasha

After her exit from the trolley, and walking a few blocks, she discovers her boyfriend, Pasha, passing out political leaflets to passers-by. As police move in to arrest him, Lara intercedes, calling him her brother and taking him away.

As they walk some distance away toward Lara’s destination, Pasha pulls out some more leaflets from his pockets and continues to hand them out to the throng of passers-by coming home from work. She scolds Pasha for his activism, worried for his safety:

Lara: Pasha, please.

Pasha: It’s got to be done.

Lara: Pasha, why has it got to be done?

Pasha: For them. For the Revolution.

Lara: Pasha, they don’t want a revolution.

Pasha: They do. They don’t know it yet,

but that’s what they want.

Passer By: Give me some of those, comrade [re: leaflets].

Lara: Pasha? Are you a Bolshevik?

Pasha: No, the Bolsheviks don’t like me,

and I don’t like them.

Pasha: They don’t know right from wrong.

Lara: Pasha Antipov, you’re an awful prig – a self-righteously moralistic person who behaves as if superior to others.

Lara: People gossip round here.

Pasha: It’s the system, Lara.

Pasha later tells Lara that people will be different after the Revolution. And he asks Lara if she will come to an evening march planned by Pasha and his activists. No, she won’t attend, she explains, saying she must focus on her school work “I’ve got exams to take, Pasha. I’ve got to get my scholarship.”

Victor & Lara

Some nights later, Victor Komarovsky, comes to Amelia’s dress shop expecting to take Amelia out for night of dinner and dancing, However, Amelia is ill, running a fever, and she urges Victor to take young Lara in her place, which he does.

At the restaurant, Victor is recognized by the patrons, as he and young Lara are shown to their table. They order their meal and Victor then takes Lara to the dance floor.

A bit later there, a commotion is caused by some demonstrators in the street, to which Victor scoffs at and exclaims: “No doubt they’ll sing in tune after the revolution” — which brings laughter from those in the restaurant as the evening’s activities resume.

Later that night, traveling by horse-drawn sleigh across the city, Victor takes Lara to his home and seduces her before returning her to her mother’s home.

Street Slaughter

Meanwhile, that same night, the group of socialist demonstrators that Victor had scoffed at in the restaurant, had assembled on the streets to continue their rally. With a band and banners in protest of the Czarist regime, they continued their march trough the streets of Moscow. However, at the opposite end of one street, was the Czar’s cavalry laying in wait.

As the protestors, led by Lara’s boyfriend, Pasha, made their way down the street, the Cossacks on horseback came charging full bore through the crowd, swinging their sabres at will. The protestors are slaughtered by the dozens, leaving pools of blood in the snow as the Cossacks conclude their handiwork.

Zhivago Shaken

Yuri Zhivago, who happened to have come to the street-side balcony of his home when he heard the demonstrators’ music, witnesses the entire event, and is visibly shaken by the killing and mayhem.

He then goes down into the street and begins to care for the wounded. As soldiers are loading bodies into wooden wagons, Zhivago is told by a soldier on horseback he should get off the street and go back to his home. But Yuri is boiling mad with barely-contained anger and is saved from a confrontation by his uncle Gromeko (Ralph Richardson) who takes him off the street, reminding him that Tonya will be arriving the next day from Paris.

Pasha Wounded

Lara’s boyfriend, Pasha has been wounded in the street battle, his face sliced on one side by a Cossack sabre. He has come to Lara after the battle, and she says he should go to the hospital, but Pasha is afraid to go there, fearing arrest. He asks for iodine and treats the wound himself.

“There were women and children,” he explains to Lara, “and they rode them down. Starving women, asking for bread.”

Pasha had also picked up a dropped hand gun off the street during the battle. He asks Lara to hide the gun and keep it for him. Lara is horrified but hides the gun away in a drawer.

Some days later, on the other side of town, Yuri Zhivago is nearing the end of his medical studies.

Russian Comfort

Although the seeds of Russian discontent are stirring as Pasha and the demonstrators make plain, it is still a few years before World War I and the Russian Revolution at this point.

Life for the upper classes in Czarist Russia is quite good and comfortable – as it has been for the Gromekos in Moscow and Yuri Zhivago growing up there.

One scene from the film has Zhivago arriving at the Gromeko’s fashionable town home in Moscow where he has lived, meeting Anna Gromeko. That afternoon, she has a letter for him from Tonya, then in Paris, but soon to be back in Moscow.

When Tonya arrives to return to the Gromeko household from Paris, she is met at the rail station by her parents, Alexander and Anna Gromeko, along with Zhivago. It is 1913.

Tonya and Zhivago are excited to see one another, as they are expected to marry. Tonya tells Yuri that his poetry is famous in Paris, and has brought him a publication with the news on his work.

The affair between Victor Komarovsky and Lara, meanwhile, continues in secret. Victor has Lara coming to private rooms where they meet. He insists she wear clothing he buys for her, and plies her with food and drink. But Lara feels trapped.

Suicide Call

The following winter, as Zhivago and Tonya attend a music recital, Yuri’s medical school mentor and doctor, also at the recital, is summoned on a medical emergency to treat a woman who has attempted suicide. Zhivago goes with him to assist.

Turns out the victim is Lara’s mother, Amelia, who has learned of her daughter’s affair with Komarovsky. The senior doctor is a friend of Komarovsky’s.

Komarovsky, cad that he is, does not want to loose Amelia to suicide over his affair with Lara. The two doctors manage to save her.

But it is here where Zhivago first sees Lara, as he wanders through the house, and through a window to another room, observes she and Komarovsky having a conversation about her mother’s condition and that she has learned of their affair.

Victor Meets Pasha

Lara, however, is trying to free herself from Komarovsky, and has asked him to meet with she and Pasha at a local restaurant, and hear of their plans to marry.

The meeting is tense with Pasha asserting himself and his experience. He is 26, and believes himself capable of marriage.

Komarovsky does not argue with Pasha at the restaurant, but later, at the dress shop, attempts to dissuade Lara from marrying Pasha:

Komarovsky: Lara, I am determined to save you from a dreadful error. There are two kinds of men, and only two, and that young man is one kind. He is high-minded. He is pure. He is the kind of man that the world pretends to look up to and in fact despises. He is the kind of man who breeds unhappiness; particularly in women. Now, do you understand?

Lara: No.

Komarovsky: I think you do. There’s another kind. Not high-minded. Not pure. But alive. Now that your taste at this time should incline towards the juvenile is understandable. But for you to marry that boy would be a disaster. Because there’s two kinds of women… [Lara covers her ears, but he forces her arms down]

Komarovsky: There are two kinds of women and you – as we well know – are not the first kind. [Lara slaps him, and he slaps her back].

Komarovsky: You, my dear, are a slut.

Lara: I am not!

Komarovsky: We’ll see.

Komarovsky: Who are you to refuse my sugar? Who are you to refuse me anything?

…And Victor then proceeds to rape her.

Revenge Plan

Humiliated, Lara plans to take revenge on Victor. At first, she plans to take the gun Pasha asked her to keep for him and use it to shoot Victor at his home.

One cold winter evening, she sets out to do the deed, heading to Victor’s residence, only to discover Victor has gone to a Christmas party that evening, where she goes next.

Along the way, Pasha sees Lara on the street and insists on knowing where she is going, but Lara tells him he should read the letter she has left for him, which explains the whole story, including her affair with Komarovsky.

But Lara continues to make her way to the Christmas party, despite Pasha’s queries, though Pasha lingers on the street suspecting something.

At the party, there is much frivolity, with Christmas-tree candle-lighting, music, and dancing. The engagement announcement of Zhivago and Tonya is also expected that evening.

Shooting Victor

Having entered the elegant gathering, Lara makes her way through the crowd of party goers, moving toward the back of the hall where a card game is in progress. Komarovsky is there with cigar and drink in hand. Lara moves closer, draws the gun and aims at Komarovsky, and shoots. All the festivity stops instantly with the sound of the gunshot, amid some screams. Lara’s shot, however, has only slightly wounded Victor, hitting his arm.

Zhivago and Tonya witness the incident, as Zhivago is privately quite taken with Lara’s courage. Some in the crowd call for the police, but Komarovsky insists no action be taken against Lara.

At about that time, Pasha, who followed Lara to the party, comes into the hall. As he moves to retrieve Lara from the scene, the crowd makes way for him, then escorting Lara out of the hall.

Komarovsky, meanwhile, is treated for his wound by Zhivago, during which the two have this exchange:

Zhivago: What happens to a girl like that, when a man like you is finished with her?

Komarovsky: You interested?

Zhivago: [abruptly removing the cigar from Victor’s mouth, tossing it into the toilet]. You shouldn’t smoke. You’ve had a shock.

Komarovsky: I give her to you, Yuri Andreevich. Wedding present.

Few Years Later

Flash forward a few years later. Yuri and Tonya are married in Moscow and have a young son. Pasha and Lara have left Moscow for the countryside. Although devastated by Lara’s admission of her affair with Komarovsky, Pasha married Lara, and they have a daughter, Katya. Pasha soon enlists to fight for the Russian Army, but later is said to be missing in action or possibly dead. Lara enlists as a nurse to treat soldiers in an attempt to find Pasha.

Lara and Pasha, now married, are shown here with their daughter, living in the country. On one visit to town, shown here, Pasha meets with a recruiter and joins the army. However, later, he would go missing in action.

In 1914, World War I erupts and Yuri is posted to a field unit of the Russian Army near Ukraine After one bloody insurrection and roadside battle scene, with dead and wounded strewn about, he happens to find Lara at the scene and recruits her to assist him in treating the wounded. Together, they then help run a field hospital for six months.

On the back of their hospital wagon, on a makeshift operating surface, Zhivago is at work on a wounded soldier as nurse Lara assists in dabbing the wound with swab.

Dr. Zhivago and nurse Lara on their hospital wagon.

But Yuri also adds that the young man who escorted her out of the hall that night, her future husband, Pasha, now missing in action, had shown “a lot of courage. He made the rest of us look very feeble. As a matter of fact, I thought you both did.”

Of Komarovsky, Yuri says, “good man to shoot at.”

World War I for the Russians had begun to wind down in 1916. But by the summer of 1917, the October Russian Revolution has begun, changing the entire political landscape. Yuri and Lara, meanwhile, continued their medical work by order of the Provisional Government.

One day at the field hospital, news circulars report that Lenin has arrived in Moscow, the Tsar is in prison, and that civil war – the Revolution – has begun. “No more Tsars!...Only workers in a workers state!,” says one soldier.

World War I for the Russians had begun to wind down in 1916. But by the summer of 1917, the October Russian Revolution has begun, changing the entire political landscape. Yuri and Lara, meanwhile, continued their medical work by order of the Provisional Government

Having worked together for six months in an old country estate converted to a hospital, Yuri and Lara are the last to leave the now empty facility. They are clearly in love with each other, but have managed to keep their passions suppressed.

As the fighting winds down, and the field hospital empties of its wounded, Yuri and Lara talk of their respective departures, as Lara resists Yuri pressing her about their, so far, repressed love for each other.

Yuri in one scene, as Lara works on some ironing, presses Lara for what has grown between them, Lara is set to rejoin her young daughter in the town of Gradov, where she and Pasha had initially settled. Yuri worries about who will take care of Lara, but says he would be jealous of any caretaker. Zhivago then moves closer to Lara, but she resists, telling Yuri they have done nothing that would violate his marriage to Tonya, and so should remain that way…

Lara: “…Zhivago, don’t…My dear, don’t – please (as she burns her ironing)….Now, look what you’ve made me do. Yuri, we’ve been together six months on the road, in here, and we haven’t done anything you have to lie about to Tonya. I don’t want you to have to lie about me. You understand that, Yuri? You understand everything…”

Closing of film scene after Lara has left Zhivago and the field hospital.

Music Player

“Lara Leaves Yuri”

Doctor Zhivago Soundtrack

In the moment, Yuri’s eyes fill, and “Lara’s Theme” is heard in the film score, as the scene fades into the back rooms of the now empty hospital, passing a vase of wilting sunflowers Lara had set.

Back to Moscow

Back in Moscow, Yuri’s wife, Tonya has been living in the family home with their young son and her father, Alexander Gromeko. The letters home from Yuri were not always regular, and she is now looking forward to their reunion, having received word of his return. In the film, she is shown in one scene on the balcony of their home looking out over the Moscow streets, as Yuri approaches from afar. During his time away, however, radical change has occurred throughout Russia — including at the family home in Moscow — as Yuri soon discovers.

Tonya, anticipating Yuri’s homecoming after the war, looks out from the balcony of her home over the streets of Moscow, and she will soon become excited seeing Yuri approaching in the distance.

When Yuri arrives at the once-elegant home in Moscow where he was raised, Tonya introduces him to “Comrade Yelkin, our local delegate. He lives here.” In fact, 13 families now live there. Next is “Comrade Kaprugina is the Chairman of the Residents’ Committee,” who asks for Yuri’s discharge papers. He learns his former hospital, Holy Cross, has been renamed, “The Second Reformed Hospital.” Yuri quips: “Good. It needed reforming.” In the course of conversation about his return to medical work, he notes there’s typhus in the city, to which one comrade replies, “You’ve been listening to rumormongers. There is no typhus in our city.”

As Yuri enters the once-elegant Gromeko home in Moscow where he was raised, he is introduced to local party officials and learns from Tonya that the home is now divided into units for 13 families.

Collectivization has begun, but Moscow is in trouble, with virtually no food supplies or heating fuel, as an unforgiving Russian winter approaches. One night, in fact, Yuri is driven to steal some fence boards for needed fuel at home, but is observed in the theft by Yevgraf, his half brother, who is now a party official. Yevgraf does not arrest Yuri, but follows him home, where the two connect and reunite as family.

Half-brother Yevgraf with Yuri at home after fence-wood pilfering, arranges for Yuri & family to leave Moscow.

Yevgraf urges Yuri to leave Moscow, and secures fake papers for the family to leave for the Gromeko country home, Varykino, in the Ural Mountains. A long train ride in a very crowded and dirty box car ensues with a few armed guards and one unhappy prisoner.

Along the way, as the train slows through a burned-out village, with dead cattle strewn about, a woman with child in her arms runs along side the slowed train and hands her infant to Yuri and others standing at the box car’s door, but the child is dead. Yuri and others manage to pull the woman onto the moving train, and she later explains that the local devastation is the handiwork of one ruthless Bolshevik commander known as Strelnikov, who has unfairly punished the entire village for alleged crimes.

Train w/Yuri & family slows through one village attacked by partisans; villagers seeking help. |

One woman runs along side of the slowed train, handing an infant to Yuri, later pulled aboard. |

Later in the trip, their train stops due to civil war activity in the area. Yuri hears the sound a waterfall in the distance and wanders off into the woods and away from his train, as strains of “Lara’s Theme” are heard. Then he suddenly comes to a cut in the terrain and there, on another rail siding, is Strelnikov’s hulking armored train. He is apprehended by guards who suspect him an assassin. They take him to Strelnikov’s private car to be interrogated.

As his own train has stopped on another siding, Yuri Zhivago has wandered off through the woods hearing a waterfall, then stumbles upon an opening where Bolshevik commander Strelnikov’s armored train is parked, and is apprehended by guards suspecting him an assassin,

Bolshevik Commander General Strelnikov (a.k.a. Pasha), amid some flying snowflakes.

In his commander’s car, Strelnikov dismisses his guards, and begins a conversation with Zhivago, having inspected his personal papers. He asks if he is the poet Zhivago, which Yuri acknowledges he is. At first, Strelnikov compliments Yuri on his poetry of old, then lectures him: “I used to admire your poetry…. I shouldn’t admire it now. I should find it absurdly personal. Don’t you agree? Feelings, insights, affections. It’s suddenly trivial, now. …You don’t agree. …You’re wrong. The personal life is dead in Russia. History has killed it.”

They soon discover they have seen each other before, six years earlier at the Christmas Eve party where Komarovsky was shot by Lara and Pasha escorted her from the hall.

Zhivago explains that he and Lara were recently a medical team on the war front. “If she’s with you, I’m sure she’d vouch for me,” Zhivago says. But Strelnikov explains he hasn’t seen his wife since the war. He says she is now in Yuriatin, to Yuri’s surprise, as Strelnikov adds, with seeming indifference to his marriage to Lara: “The private life is dead… for a man with any manhood.” Yuri then quips, “We saw a sample of your manhood on the way, a place called Mink.” [i.e., the burned village].

Yuri Zhivago is questioned by Bolshevik Commander Strelnikov in his private rail car, and he realizes Zhivago has seen him before, and charges that poetry and affections are now trivial and that the “personal life” is dead in Russia.

Strelnikov: They’d been selling horses to the Whites.

Zhivago: No. It seems you burnt the wrong village.

Strelnikov: They always say that, and what does it matter? A village betrays us, a village is burnt. The point made.

Zhivago: Your point, their village.

Suspicions that Yuri was an assassin or spy are dismissed by Strelnikov, and he releases Yuri, who runs back to his own train that has nearly left without him. As their journey proceeds, they soon arrive at Yuriatin, and then by horse-drawn carriage, to the Gromeko summer home at Varyikino

Varykino

When they arrive at the family summer house at Varykino it is late winter/ early spring. The main house, they find, is locked and boarded up; under seal of the local communist authorities. Alexander Gromeko, the owner, is angry and about to break down the door. Occupying it, however, would be a crime and would risk their arrest. But also on the estate is a small gardener’s cottage nearby, and they make their way there to see if it’s open.

Finding Varykino boarded up and under communist seal, Yuri, Tonya, their son Sasha, and Alexander Gromeko, with porter, make their way to caretakers’ cottage, also on the estate.

After a quick inspection of the cottage, they find it open and livable and settle in for what is expected to be a multi-year stay, later managing a vegetable garden there for food. Their squatter’s residence at this location is nearly invisible. That summer, however, they learn of news that the Czar and his family have been executed. The family remains in the cottage through that winter and into the spring.

Yuri Zhivago and his extended family, settle in at the gardener’s cottage at Verykino, later shown here with Tonya tending a vegetable garden.

Life in their rural hideaway is simple and calm – perhaps too calm for Yuri, although he is shown time and again discovering meaning and purpose in the everyday world around him, as in one scene where he is taken with the formation of ice crystals on a window pane.

At Varykino, in winter’s doldrums, Yuri finds wonder in a window pane’s ice crystals. |

...But soon, the rising biology of spring at Varykino stirs the soul of Yuri Zhivago... |

But one day, moved by his restlessness, and the encouragement of Tonya, he rides by horseback into the town of Yuriatin with plans to visit the library there that his step-father, Alexander Gromeko, has recommended. In Yuriatin, Zhivago finds Lara working in the library, who is quite astonished to see him. “Zhivago! What are you doing here?” The two then take a long walk through the war-scarred town as he explains the trip he and family have made from Moscow, that they are living at Varykino, and that he has also met Strelnikov.

On his trip to Yuriatin, Zhivago finds Lara at the local library, where she is surprised to see him, as the two reunite, walk through town, and catch-up on their respective lives.

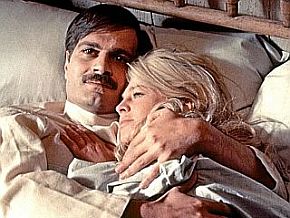

Lara has lived in Yuriatin for about a year, having returned there in search of her husband, Pasha, now known as Strelnikov. As their walk through town continued, they end up at Lara’s apartment where Yuri appreciatively takes in Lara’s living space and her domestic touches. She lives there alone with her young daughter, Katya, who Lara says is currently in school. Whereupon, the two embrace, kiss passionately, and move to Lara’s bedroom to consummate their long-delayed love affair as “Lara’s Theme” permeates the scene.

Zhivago and Lara, arrive at Lara’s apartment in Yuriatin, where they soon embrace... |

... and move to Lara’s bedroom where they begin their long-delayed love affair. |

Yuri Zhivago then begins something of a double life for some months, trying to be true to both his loves, periodically leaving Tonya and his home life back in Varykino to visit Lara in Yuriatin. But with Tonya pregnant, Yuri struggles with his infidelity.

Back at Varykino, with Tonya pregnant, Zhivago struggles with his infidelity.

Guilt soon gets the better of Zhivago, and he vows to himself that he must end his affair with Lara. On his next visit to Yuriatin, and at Lara’s apartment, there is tortured scene, with Lara crying as Yuri tells her their affair must end, and this will be the last time they will see each other. On the horseback ride back to Tonya and Varykino after leaving Lara, Zhivago slows his horse down to a near stop on a dirt road in the middle of a forest, rethinking what he has just done with Lara, feeling sad and torn between his two loves.

On the road back to Varykino, as he has slowed his horse in thoughts of Lara, Yuri is surrounded by soldiers. |

Captured by Red Army partisans, he is told that he is now conscripted to serve as their doctor. |

And just then, on a this remote forest road, he is surrounded by local partisans on horseback who take him prisoner, with their commander explaining they have been watching him and know all about his affair in Yuriatin and his residence at Varykino. They are in need of a doctor, he is told, and so, they are conscripting him for involuntary service in their cause. For the next two years, Zhivago rides with these partisans, attends to their wounded, and once again, witnesses the horrors of war close up.

Sometime later, after his capture, on one of the army’s long and weary treks, Yuri slowly but deliberately drifts away from the unit on horseback, and then escapes ( at that point, he is regarded as a deserter by the Red Army). He later loses his horse, but continues his trek on foot over the unforgiving snow-covered landscape, following old roads and telegraph lines trying to get back to Varykino and Yuriatin.

After escaping the Red Partisans, Zhivago loses his horse makes a long journey on foot back to Yuriatin. |

Yuri eventually makes his way hundreds of miles back to Yuriatin. Arriving at Lara’s apartment alone after his ordeal, frostbitten and dehydrated, he is horrified at seeing himself ravaged and emaciated in a mirror there. |

On his way, through one blizzard, he begins hallucinating and believes he sees his family, Tonya and Sasha, ahead as distant figures. He starts following and calling to them, but upon reaching them, discovers it is another family, whom he has scared. He eventually makes his way back to Lara’s apartment in Yuriatin, remembering where she had hid the key. Inside, he sees himself in a mirror, and is horrified by his ravaged and emaciated appearance. Lara, hearing he was sighted in the area, had gone to Verykino looking for him, returns to her apartment to find him and begins nursing him back to health.

After his ordeal and arrival at Lara's apartment, she helps nurse him back to health.

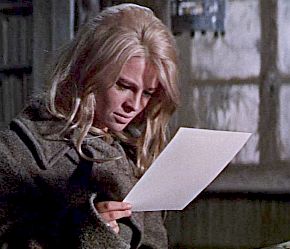

At Lara’s, with her care and feeding, there is a long period of recovery for Zhivago, having suffered from severe frostbite, as he slowly begins walking again. During his recovery, Lara has explained to him that Tonya had contacted her while searching for him, leaving his belongings with her. Tonya also sent Lara a sealed letter for Yuri, which Lara gives to Yuri during his recovery, then learning that Tonya had given birth to their daughter, and that she, her father, and the two children were now in Paris.

At Lara's apartment during his recovery, Zhivago reads the letter Tonya has sent him via Lara, then learning about his second child and his family now in Paris.

Zhivago and Lara, meanwhile, continue their relationship in Yuriatin until – above all unexpected intrusions – none other than Victor Komarovsky arrives at their door on a cold snowy night.

None other than Victor Komarovsky arrives at Lara's apartment door one cold winter night to tell then they are in danger and to make the couple an offer of safety in the East.

Komarovsky explains that they are in danger, and that he has come to offer them help and a safe haven in the east. Cheka agents have been watching them due to Lara’s marriage to Strelnikov, Yuri’s desertion from his Red Army captors, and his counter-revolutionary poetry.

Komarovsky: Yuri Andreyevich, you spent two years with the Partisan’s 5th Division. You have no discharge, so you are a deserter. Your family in Paris is involved in a dangerous émigré organization. Now, all these are technicalities. But your style of life…everything you say, your published writings, are all flagrantly subversive. Your days are numbered…unless I help you. Do you want my help?

Zhivago: No.

Komarovsky continues to explain that he has been appointed as an official to the Far Eastern Republic, and offers to take them with him. “…You come with me as far as the Pacific Coast. From there you can go where you like. To Paris, or not….” They decline his offer again. But Komarovsky persists, angering Zhivago who proceeds to throw him out of the apartment, down the steps, and into the snow. Komarovsky yells recriminations back at Zhivago in an angry tirade: “I came to you in good faith….Stay here then, and get your desserts! Your desserts, do you hear me? Do you think you’re immaculate? You’re not immaculate!…I know you! Do you hear me?! We’re all made of the same clay, you know! Clay! Clay!…”

Realizing they are in danger now – and as Komarovsky has said, their days are numbered – they know if they attempt to flee by train they will be instantly arrested. So they opt, instead, to hide out at Varykino, together, with young Katya.

Lara, Zhivago and Katya arriving by horse-drawn sleigh at snow-covered Gromeko house at Varykino to hide out from the Red Army for as long as they can.

Even if they stay at Varykino for only a short time before they are found, Lara and Zhivago believe the time spent together will be worth it. So they make their way there by horse-drawn sleigh and occupy a small portion of the old great house – which now, in the dead of winter, has the look of a frozen ice palace inside and out. They stay there through most of the remaining winter.

Lara and Zhivago entering the frozen interior of the Gromeko home at Varykino, which has taken on the look of a winter-wonderland ice palace.

During their stay at Varykino, Zhivago sometimes works on his poetry at night, amid howling wolves, which frighten Lara. But Zhivago does complete one set of poems – these dedicated to and about Lara – which she finds one morning; poems, when published, will become famous for Zhivago, though banned by the party as subversive.

Yuri Zhivago, working on his poetry at night during his and Lara’s hide out at Varykino. |

Lara discovering a poem from Zhivago about her one morning at Varykino – of a later-to-be famous collection, |

Komarovsky, now the Minister of Justice, soon finds Lara and Zhivago at Varykino, arriving one day by horse-drawn sleigh with armed guards. He once again makes his offer of help – now to leave Russia with him on his special train at Yuriatin heading for Mongolia. But once again, they refuse. Komarovsky then takes Zhivago aside for a private conversation.

Komarovsky finds Lara and Zhivago at Varykino and offers them passage on his train East, but they resist, at which point Komarovsky takes Zhivago aside to detail the dangers that Lara & Katya now face if they stay.

Komarovsky explains that Strelnikov was captured only five miles from there, and during interrogation, “insisted they call him Pavel Antipov (i.e. Pasha)… and refused to answer to the name of ‘Strelnikov’ On his way to execution, he took a pistol from one of the guards and blew his own brains out.” Now, he says, they will be coming for Lara.

Komarovsky: …But don’t you see her position? She’s served her purpose (re: as lure for Strelnikov). These men who came today as an escort will come for her and the child tomorrow as a firing squad….But if you’re not coming with me, she’s not coming with me. So are you coming with me? Do you accept the protection of this ignoble Caliban on any terms he makes? Or is your delicacy so exorbitant…that you would sacrifice a woman and a child to it?

Yuri gives Lara his mother’s balalaika, as she prepares to depart on Komarovsky’s sleigh, suspecting Yuri’s plan.

Yuri also gives Lara his mother’s balalaika, a sign to Lara that Yuri may not be coming, as they exchange glances.

In the sleigh, there are only enough additional seats for Lara and Katya. Zhivago says he will follow later with their own sleigh, meeting them in Yuriatin where the train is waiting.

However, Zhivago cannot leave his homeland, and will not join them on the train waiting at Yuriatin.

As Komarovsky’s sleigh and armed guards pull away from Vayrykino with Lara & Katya aboard, Zhivago has promised to follow later with their sleigh – but Lara, looking back, already knows that Yuri is not coming.

As Komarovsky’s sleigh, with Lara and Katya aboard, pulls away, Zhivago waves goodbye, then quickly rushes to an upstairs window high atop Varykino, frantically rubbing off the window frost, then breaking out the glass, to get a final glimpse of Lara leaving as their sleigh disappears over the far horizon.

Yuri Zhivago is devastated as Lara pulls away from Varykino on Komarovsky’s sleigh, but knows it is the best option for the safety of Lara and Katya – though for himself, he cannot leave his homeland.

Lara and Komarovsky wait for Yuri on the train at the Yuriatin station, but he does not arrive, as Komarovsky quips to Lara: “Well, I’m afraid that’s it, my dear. Your young man’s not coming,” to which Lara replies: “You fool. Did you really think he would come with you?” The train leaves, and Lara also announces to Komarovsky that she is pregnant with Yuri’s child.

Eight Years Later

Yuri Zhivago, some time later, made his way back to Moscow, where he was found by his half brother Yevgraf in poor condition and without work. Yevgraf helps him get his old job back at the hospital, but he was not in the best of health. Then one day while riding on a streetcar, Yuri believes he sees Lara walking on the street just below his streetcar window.

Yuri Zhivago, 8 years later, riding on a Moscow streetcar, gazing out the window... |

...when he believes he sees Lara walking on the street, just outside the streetcar... |

He attempts to get her attention at the streetcar window, but failing that, desperately makes his way through the crowded car to exit, reaching the street not long after she has gone by, maybe 20-to-30 yards ahead of him.

Having exited the streetcar, Zhivago then tries to run after Lara, just ahead, attempting to catch up to her... |

But as he attempts to run and call after her, he grabs at his chest, has a heart attack, and falls dead on the street. |

But as he tries to call to her and run after her, not far away, he grasps at his chest and collapses on the street. Lara has seen none of this, continuing her walk and disappearing around the corner, as passer-bys on the street rush to help the fallen Zhivago, now dead of a heart attack.

At the cemetery, a steady line of mourners & admirers attend the burial service for Zhivago, surprising half-brother Yevgraf (standing at center red collar), not realizing the popular appeal of his brother’s poetry.

Later, at a graveyard memorial service for Zhivago, large numbers of people are shown filing past his gravesite where his half brother, Yevgraf, stands in silence. The large turn out of admirers surprises Yevgraf, not realizing the wide appeal of his brother’s poetry.

At Zhivago’s burial, Lara meets Zhivago’s half brother, Yevgraf, for the first time, seeking his help to find her missing daughter lost during the Far East civil war.

One of those who come to the graveyard memorial is Lara, who meets with Yevgraf and asks his help in trying to find her missing daughter, Tonya, who was lost somewhere near Mongolia during the far east civil war. Yevgraf and Lara then search Moscow’s orphanages, but Tonya is not found. Yevgraf loses contact with Lara, and assumes she “vanished…in one of the labor camps” or passed away.

Yevgfraf with Lara (far left) visiting one of the orphanages attempting to find her and Zhivago’s missing daughter. But their search is not successful.

Yevgraf concluding his session years later with the believed-to- be missing daughter of Lara and Zhivago.

Cover of 32-page MGM press booklet on “Doctor Zhivago” film, 1966. Cover shows scene from film of Russian partisans on horseback assembling in forest, early morning.

Reaction & Legacy

As noted at the beginning of this story, the 1965 MGM film, Doctor Zhivago, became one of the most popular and top grossing films of the 20th century ($2 billion & still counting). And it remains to this day, in the 2020s, a much loved film around the world. But at the time of its initial release, the film did have its critics – some unsparing in their views.

Bosley Crowther, for the New York Times, in a December 23, 1965 review, charged that “Mr. Bolt [screenwriter] reduced the vast upheaval of the Russian Revolution to the banalities of a doomed romance.” Brendan Gill of The New Yorker in January 1966 called the film “a grievous disappointment…” and lamenting what he found as a lack of movement, also cited it as, “one of the stillest motion pictures of all time….” Film critic David Thomson, wrote in The New Biographical Dictionary of Film: “Zhivago is a syrupy romance, without poetry or plausibility.” Pauline Kael also panned the film in April 1966 for McCall’s, writing at one point: “Neither the contemplative Zhivago nor the flux of events is intelligible, and what is worse, they seem unrelated to each other… It’s stately, respectable, and dead.” Another reviewer for The Monthly Film Bulletin noted in June 1966 “the spirit of the novel has been lost.”

But the film also brought solid praise in other early reviews. In December 1965, Time magazine called the film “literate, old- fashioned, soul-filling and thoroughly romantic.” Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times described the film “as throat-catchingly magnificent as the screen could be, the apotheosis of the cinema as art…” And Clifford Terry of the Chicago Tribune wrote that David Lean and screenwriter Robert Bolt “have fashioned out of a rambling book, a well controlled film highlighted by excellent acting and brilliant production.”

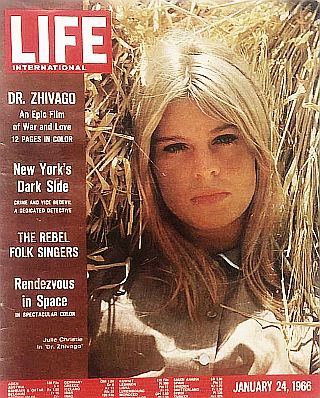

James Powers, writing for The Hollywood Reporter in December 1965, described the film this way: “Zhivago is a story about the clash between man and the state, the imperishable, resilient individual refusing to be patterned or flattened.” Life magazine’s film critic, Richard Schickel, had a detailed full-page review of the film in January 1966, calling it “a work of serious genuine art” (more on that review below).

January 1966. “Doctor Zhivago” received a generous 12-page photo spread in Life magazine editions, with Julie Christie featured on the cover of its international edition.

The review of the film by Richard Schickel at Life was also revealing of the film’s powerful cinematography and its messages:

The most important thing one carries away from David Lean’s movie version of Doctor Zhivago is a series of visual impressions – of the vastness of the Russian landscape, of the hugeness and, therefore, the uncontrollability of the forces necessary to effect revolutionary change within such a landscape, of the puniness of man when he measures himself against this scale, and finally, and most important, the nobility and the sadness of the luckless individual who would, contrary to Tolstoy’s advice, set himself in opposition to the gigantic historical pressures generated in this almost immeasurable caldron.

Schickel also addressed criticisms that the film gave short shrift to the Russian Revo-lution:

…It is true that his principal characters do not confront the great historical events of the period directly, but to have done so would have been to falsify Pasternak, who was similarly reticent;… The whole point is that in the revolutionary situation Pasternak’s characters must all remain on the margin, doomed by Marxist historical science – not to mention the raw psychology of revolution – to the junk heap of history. It is artistically essential that they be unable to participate in, shape or even fully understand the events that are transforming their lives. The compassion one comes to feel for them is based on their stubborn humanity. They accept their fate, they try to keep going, they even manage to be perversely cheerful on occasion, though it is becoming increasingly clear to them that what they are undergoing is not just a passing storm but a total and irrevocable change in the climate.

25 December 1965. Omar Sharif on the cover of “Saturday Review,” with story by film critic, Hollis Alpert.

And that’s OK – or it least it should be.

To show love and emotion and “the personal life” surviving in spite of repressive politics and the chaos of war and revolution is a good thing, no?

A world with a perfect politics made of a repressive ideological order without emotion and culture is not a world most of us would want to live in.

Again, as Robert Ebert put it: “‘Doctor Zhivago’ believes that history should have a lot of room for personal feelings – that the problems of its little people do amount to more than a hill of beans [paraphrasing Casablanca]- and that’s perhaps why the Russians [i.e, Soviet government] didn’t like Pasternak: He argued for the individual over the state, the heart over the mind.”

David Lean, in fact, had stated at the outset, that his intention in making the film was to craft Zhivago as an epic with a love story at its center. The plan was to minimize the role of the Russian Revolution and maximize the character of Lara. Lean by that time was already an Oscar winning director for other epic films, such as Bridge Over the River Kwai (1957) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962). Those films won 14 Academy Awards between them including Best Picture and Best Director for both. In Zhivago, Lean wanted to tell this story with a love affair at its core, something he hadn’t done in his earlier two epics.

Director David Lean, left, during film production with his leading actor, Omar Sharif, who played Dr. Yuri Zhivago in the 1965 award-winning film, “Doctor Zhivago.” Atlantic Monthly, August 1965.

As Lean explained in an August 1965 interview with The Atlantic Monthly while making the film:

Making movies is a kind of falling in love. It’s almost entirely emotional. For instance, when I read Zhivago my common sense told me that it [making a film about it] was a terribly difficult thing to undertake, but I was so moved by the book that I thought all this must make a marvelous movie. I’ve done two films now with no women in them [Lawrence of Arabia and Bridge on the River Kwai], and I like love stories very much. I found this a superb love story. God knows how I’m going to do it, but if we’re clever enough, it’ll come out.

And indeed, it did. Lean was quick to credit his screenwriter, Robert Bolt, as a key player in crafting the film, as Pasternak’s book provided intriguing but difficult terrain, often with incomplete information on character behavior. Bolt explained some of his work on the screenplay in the Atlantic Monthly of August 1965:

Screenwriter Robert Bolt had no small task, dealing with the lengthy & complicated Boris Pasternak novel from which the film was adapted. Atlantic Monthly, 1965.

…What fascinated me about Yuri [Zhivago] was that his actions are in fact very reprehensible. He has sins of omission and commission, mostly omission, and yet you feel not merely that he could do no other, but that in some way he was right and that the only thing under these circumstances that a man of his supcrcultivated sensibilities could have done was go with the tide wherever it took him. All the characters are peccable, and yet there is the strong feeling not merely that they could have done no other but that they reacted in these very ordinary and unheroic ways with a kind of special intensity. They were ordinary people raised several notches, and this, of course, is difficult to get across dramatically.

The way to make a man have stature dramatically is to make him do things which have great stature. The whole point about this book is that Yuri does nothing that has great stature except write poetry; and how to make the writing of a poem, particularly if the poems are like Pasternak’s, seem to a cinema audience a heroic justification of what looks like a rather useless sort of life was a very considerable problem.

We did it by calculating as carefully as we could the climax of his relationship with Lara. Everything is knotted together in the desperate situation at Varykino, where the revolution is closing in on them, where the natural conditions, the fearful cold, are closing in on them. What they are doing is in practical terms nonsense, if not indeed highly irresponsible. The only justification of it is the intensity of their love for each other. We hope we have shown by this time in the film that they are unusually mature people. We are hoping that the audience will now assume that this is a kind of Tristan and Iseult situation [famous 12th century love affair], a great grand passion. And then we have tried to arrange the actual sequence so that the climax of it shall be the writing of Zhivago’s poetry. And in that way we hope to make the poetry the crown of the film….

45th Anniversary Blu-ray edition of Doctor Zhivago released, May 2010 ( 3-disc set w/ book). Click for Amazon.

True, some of the Doctor Zhivago’s touches seem overdone by today’s standards – perhaps a little too much of “Lara’s Theme,” for example, as lovely as that tune is. Yet over time, the film has held up quite well, as later reviews seem to validate.

In one “30-years-later” Chicago Tribune review on the then-restored Zhivago film headlined, “`Doctor Zhivago’ Grows Grander With Time,” film critic Michael Wilmington described the film in glowing terms as: “a magnificent prolonged tease,” “lush and tempestuous,” “visually ravishing,” and “inimitable.” And nearly 20 years after that, film director Paul Greengrass (e.g., Jason Bourne film series, Bloody Sunday, Captain Phillips, United 93), then delivering the BAFTA David Lean Lecture in March 2014, called Zhivago “one of the great masterpieces of cinema.”

At Varykino, Lara asks Yuri: “Wouldn’t it have been lovely if we had met before?” -- and they almost did, years earlier on a streetcar. (see earlier photo near top).

See also at this website, a detailed companion story to this one at: “The Pasternak Saga…and Zhivago Chronicles,” which cover the life and career of Doctor Zhivago author, Boris Pasternak, including his battles with Soviet authorities over his writing, their refusal to publish Doctor Zhivago, his Nobel prize controversy, his love affair that inspired the Lara character in Doctor Zhivago, and the CIA’s involvement with the Zhivago novel as Cold War propaganda.

Additionally, other stories of interest a this website may include the following: “Linda & Jerry, 1971-1983,” on the respective careers of, and relationship between, California Governor Jerry Brown and rock star Linda Ronstadt; “The Love Story Saga, 1970-1977,” on the book and film of that era that became a publishing and box-office hit; and, “Of Bridges & Lovers,” an account of the 1992 book and the Clint Eastwood / Meryl Streep 1995 film, Bridges of Madison County. Other story choices on film-related topics can be found at the “Film & Hollywood” category page.

Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing and continued publication of this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

__________________________________

Date Posted: 7 October 2023

Last Update: 11 November 2023

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/PopHistoryDig

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Doctor Zhivago: 1950s-2010s,

PopHistoryDig.com, October 7, 2023.

__________________________________

Other Film Choices at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“Doctor Zhivago (novel),” Wikipedia.org.

“Doctor Zhivago (film),” Wikipedia.org.

R. S. Stewart, “Dr. Zhivago: The Making of a Movie,” The Atlantic Monthly, August 1965, pp, 58-64.

“David Lean,” Wikipedia.org.

Bosley Crowther “David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago Has Premiere; Adaptation of Pasternak Novel at the Capitol; Omar Sharif and Julie Christie in Leads,” New York Times, December 23, 1965, p. 21.

Hollis Alpert, “Omar Sharif As Dr. Zhivago,” The Saturday Review, December 25, 1965, p. 20.

MGM, David Lean’s Film of Doctor Zhivago, program booklet, 1965, 36 pp.

Robert Bolt, Doctor Zhivago: The Screenplay, 1965, Random House, 224 pp. Click for copy.

“Doctor Zhivago Film Script,” DailyScript .com.

James Powers, “Doctor Zhivago,” Hollywood Reporter, December 23, 1965.

Brendan Gill, “The Current Cinema,” The New Yorker, January 1, 1966. p. 46.

Bosley Crowther, “Gone With the Purga; Re ‘Dr. Zhivago’” [re:‘Zhivago’ vs. ‘Gone With The Wind’], New York Times, January 9, 1966, Section 2, p. 1.

Arthur Knight, “Lean Pickings” (Review, Doctor Zhivago), The Saturday Review, January 15, 1966, p. 43.

Richard Schickel, “Epic Beauty and Terror: David Lean Makes a Long and Magnificent Film of Dr. Zhivago;,” Life, January 21, 1966, p. 48 (12-page spread w/photos).

Richard Schickel, “A Work of Serious, Genuine Art,” Life, January 21, 1966, p. 62-A.

Pauline Kael, “At The Movies with Pauline Kael,” McCall’s, April 1966, p. 36.

“Film Chronicle,” Commentary, May 1966, pp. 73-76.

Francis Russell, “’Zhivago’ Reduced to an Epic” (Review, Doctor Zhivago), National Review, May 31, 1966, pp. 542-543.

Michael Wilmington, “`Doctor Zhivago’ Grows Grander with Time,” Chicago Tribune, April 7, 1995.

Roger Ebert, “Doctor Zhivago,” Chicago Sun-Times, April 17, 1995.

“Doctor Zhivago,” Plot Summary & Synopsis, IMDB.com.

Chris Hicks, “Film Review: Doctor Zhivago,” Deseret News, December 29, 1995.

Scott Rosenberg, “The Story of Love, History and the Doctor,” San Francisco Examiner /SFgate.com, April 7, 1995 / Updated: February 8, 2012.

“Doctor Zhivago Reviews: Top Critics,” RottenTomatoes.com.

“Doctor Zhivago Burial Scene,” YouTube.com, posted, August 14, 2014.

“Do People Improve With Age?” [Zhivago film clip], Turner Classic Movies, TCM.com.

Doctor Zhivago (1965): “Take Him Inside” [film clip, Yuri observes street slaughter], TCM.com.

Oscar Manheim,“ Lara Shoots Komarovsky, Doctor Zhivago 1965,” YouTube.com,June 29, 2016.

“Doctor Zhivago (1965): ‘An Extraordinary Girl’” [film clip, shoots Victor], TCM.com.

Jaewook Ahn, “Doctor Zhivago: Scene 7/17 Lara Leaves Zhivago In Field Hospital,” YouTube.com, May 24, 2019.

“Lara’s Theme,” Wikipedia.org.

Jaewook Ahn, “Doctor Zhivago: Scene 8/17 Returns Home,” YouTube.com, May 24, 2019.

“Doctor Zhivago (1965): Will There Be Wolves In The Forest?” [film clip], TCM.com.

Lillian KM, “Strelnikov and Zhivago,” YouTube .com, February 26, 2014.

“Dr Zhivago in Varykino [actually, Uriatan library], YouTube.com, January 14, 2012.

Rui Garcês, “Doctor Zhivago (1965) – Yuri and Lara (HD Tribute),” YouTube.com, September 2017.

Tim Dirks, “Greatest Film Scenes and Moments: Doctor Zhivago (1965),” FilmSite .org.

Frank Miller, “The Big Idea Behind Doctor Zhivago,” TCM.com, July 26, 2004.

“Paul Greengrass: David Lean Lecture,” BAFTA.com, March 18, 2014.

BFI, “Doctor Zhivago” (new trailer 2015), YouTube.com.

Peter Bradshaw, “Doctor Zhivago Review – Vehement Storytelling Still Conjures Great Romance; With Real Contemporary Relevance,” The Guardian.com, November 26, 2015.

Paul Batters, “Dr Zhivago (1965): David Lean’s Masterpiece Of Love And Tragedy,” Silver Screen Classics, July 22, 2018.

Roderick Heath. “Doctor Zhivago (1965),” FilmFreedonia.com, September 25, 2018.

“Doctor Zhivago,” American Film Institute (AFI Catalog), AFI.com.

“Doctor Zhivago (1965),” IMDB.com.

“Doctor Zhivago (1965),” Critic Reviews, IMDB.com

“Doctor Zhivago (1965-66),” PeterViney.com

Lily Rothman, “How Hollywood Turned the Epic Book Doctor Zhivago Into a Movie

Doctor Zhivago,” Time.com, December 22, 2015.

“Doctor Zhivago (TV series),” Wikipedia.org.

“Doctor Zhivago: Anniversary Edition DVD Review,” DVdizzy.com, 2010.

Alain Silver, “David Lean, Great Directors,” SensesOfCinema.com, Issue 30, February 2004.

__________________________________

More Film Choices at Amazon.com…