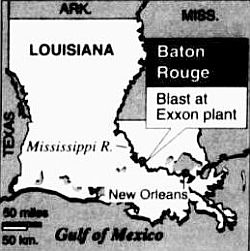

It was early afternoon on December 24th, 1989. Louisiana governor, Democrat Buddy Roemer, was at the Governor’s Mansion near the capitol building in Baton Rouge when the explosion occurred. “I heard this big blast,” he later recounted. “I was enjoying Christmas Eve with the family…” The blast didn’t break any glass, recalled the Governor, “but it blew open two big garage doors down in the basement, and those doors were locked.” In New Orleans, 75 miles away, a seismograph would record 3.2 on the Richter scale. On later newscasts at the scene, Roemer would be shown making statements about the blast, and that state officials were monitoring the surrounding area.

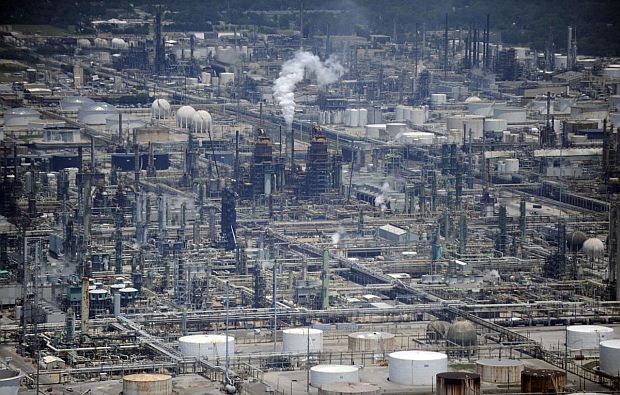

Dec 25th 1989: Exxon oil refinery in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, still smoking from a major Christmas Eve refinery explosion & fire that killed 2 and injured three, and caused property damage miles away. Photo, Sam Kittner.

The explosion had occurred at the big Exxon oil refinery just north of Baton Rouge. The giant complex was clearly visible from the upper floors of the tall state capitol building built by former Louisiana governor Huey P. Long. The explosion shattered windows in the 32-story building about 1 mile south of the refinery. The governor’s mansion is in the same area. The Exxon complex then, and still today, is huge and sprawling, located on 2,100 acres along the east shore of the Mississippi River.

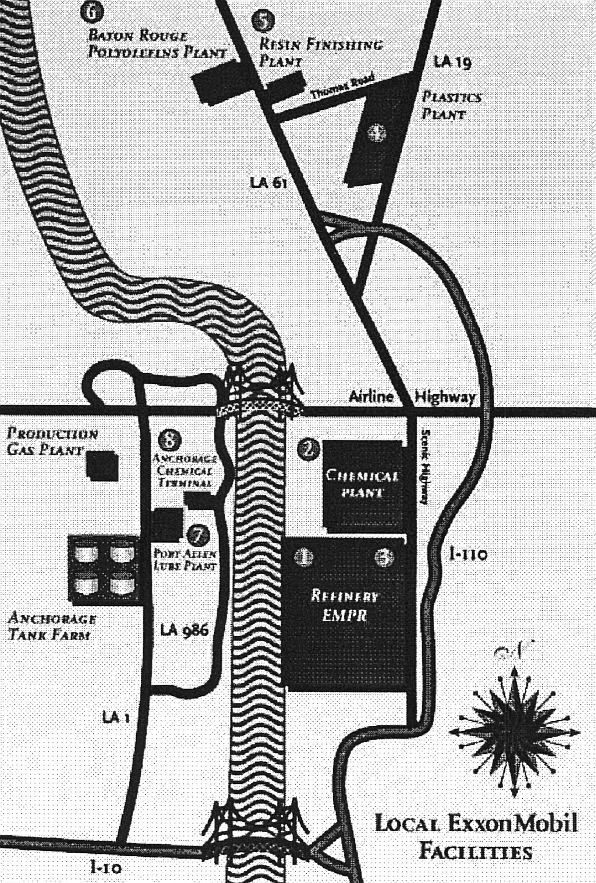

Exxon Baton Rouge, LA refinery location map.

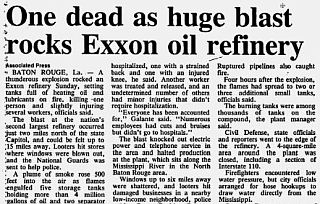

At the time of the 1989 explosion, the Exxon complex included an extensive tank farm, a web of pipelines, and a major chemical works. Following the Christmas Eve explosion, a major fire soon erupted throughout the complex. There were 16 giant oil storage tanks burning and also a score of ruptured pipelines feeding a spreading ground fire with crude, benzene, gasoline, LPG, and other flammable products.

The refinery at that time was the second largest in the U.S., producing 500,000 barrels-a-day, while the chemical plant produced 350,000 barrels-a-day of petrochemical products.

Running through the Exxon complex then, as a main supply artery, was a three-tiered pipe band carrying some 70 lines, most of them bringing product to and from the docks on the Mississippi River. One of the lines in the top tier of the pipe band delivered natural gas from a well located 57 miles south. These were among the lines that had erupted in the explosion, feeding the ground fire. In all, some 17 lines in the pipe rack were ruptured by the explosion.

A local TV news frame offers another perspective on the 1989 Christmas Eve explosion at Exxon’s refinery, where at one point, 16 oil storage tanks with crude, benzene, gasoline, and other products were ablaze.

Initial reports had at least one worker killed, with several others injured. A plume of smoke rose 500 feet into the air as the fire proceeded to engulf at least five of the big tanks holding more than 4 million gallons of oil. Four hours after the explosion, the flames had spread to additional small storage tanks. Two separator units at the refinery, which separate water from oil, were also burning. The explosion knocked out electric power and telephone service in the area. “I witnessed a 30-foot-tall, 40-foot-diameter slop tank blow completely off its foundation and land in the middle of a pipe band 500 feet away. I’d never seen a sight like that before.”

– Fire Chief, Jerry CraftWindows were shattered up to six miles away. Looters raided stores whose windows were blown out and Governor Roemer activated the National Guard to help police. A four-square-mile area around the plant was closed, as well as a section of Interstate 110, but no evacuations were ordered..

One of the fire chiefs at the scene, Jerry Craft, reported that the emergency was bigger than simply a problem at one refinery unit. “The heat load from all the tank fires and the ground fires was incredible,” he said. “I witnessed a 30-foot-tall, 40-foot-diameter slop tank blow completely off its foundation and land in the middle of a pipe band 500 feet away. I’d never seen a sight like that before.”

At one point, there were 16 storage tanks burning, a number of which were smaller tanks under 60 feet in diameter. Others were twice that size, each capable of holding more than 100,000 barrels of oil or petroleum product. Some of the tanks burned for four days, or until their fuel was exhausted.

1989 WAFB-9 TV news footage of roiling storage tank fires, shot from a helicopter, offering a closer view of part of the refinery inferno that raged following Christmas Eve 1989 blast at Exxon’s Baton Rouge, LA refinery.

Fire chief Jerry Craft and his fellow firefighters soon discovered one of the two fatalities at the scene: a contract worker trapped inside a burning pickup truck. Craft and another firefighter, in an effort to retrieve the driver, tried to open the truck’s doors, “but we couldn’t get him,” he said. “It was an extended cab Ranger and it just collapsed like an accordion. We almost burned the gloves off our hands trying to get him out.”

Governor At Scene

LA Governor, Buddy Roemer, speaking with the press after Dec 24, 1989 explosion at Exxon.

During the blaze, firefighters encountered low water pressure, but city officials arranged for hose hookups to draw water directly from the Mississippi River.

In Baton Rouge, the plate glass fronts of stores on the Riverside Mall, a half-mile street that extends to the state capitol grounds, were blown out.

Early Associated Press reporting on the 1989 explosion & fire at Exxon’s Baton Rouge refinery, where 2 workers would die |

Longer view of the Exxon Baton Rouge refinery and Louisiana state capitol building following December 1989 explosion. |

Governor Roemer, who had called up 50 National Guardsmen, surveyed the Baton Rouge area by helicopter and landed at the plant site. He told reporters there that state Department of Environ-mental Quality staff members were on the scene and had no evidence of toxic releases from the blast. State Police Hazardous Materials and Tactical units also were on duty inside and outside the plant.

The refinery burned some 15 hours before fire crews were finally able to put them out around 5 a.m. Christmas Day.

After an investigation a year later, it was determined that the explosion and fire were caused by corrosion of a pipeline. In neighborhoods along the southern and eastern boundaries of the refinery, homes were damaged by the explosion, and the incident would generate some 8,000 damage claims by residents.

A “30-years-later” look back at the Christmas Eve explosion by a local TV outlet, concluded in part, that Exxon had learned a great deal from the 1989 incident, and that it’s operations had improved. But during 1989 and early 1990, Exxon had troubles beyond its Baton Rouge explosion, suggesting a possible broader company-wide problem.

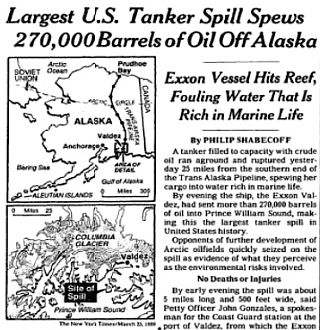

New York Times front-page story on the historic March 24th, 1989 Exxon Valdez oil tanker spill in Alaska’s Prince William Sound – then the largest oil spill in U.S. waters.

Exxon’s Bad Year

The year 1989 wasn’t exactly a high point for Exxon. On March 24th, 1989, the Exxon Valdez oil tanker, shipping out from Alaska and bound for Long Beach, California, struck Prince William Sound’s Bligh Reef at about midnight, spilling 10.8 million gallons of crude oil in Alaskan coastal waters over the next few days. The spill – one of the worst human-caused environmental disasters in U.S. history – would become the second largest in U.S. waters; after only BP’s May 2010 Deepwater Horizon blow-out in the Gulf of Mexico. The oil slick from the grounded tanker spread as far as 500 miles from the crash site and affected 1,300 miles of shoreline. In the years following the Valdez spill, Exxon became known as a no-holds-barred litigator, appealing endlessly to push back verdicts, reduce awards, and wriggle out of timely and meaningful accountability, though it would pay some fines and suffer reputational damage.

However, the same tenacity Exxon used in the courtroom, apparently did not appear to apply to how the company ran its facilities. Neither the Baton Rouge explosion, nor the Exxon Valdez oil spill, were the only incidents Exxon had in 1989. A few weeks before the Exxon Valdez ran aground, half a world away off Oahu, Hawaii, another Exxon tanker, the Exxon Houston,In 1989-90, Exxon also had big spills off Hawaii and at its giant Bayway refinery in New Jersey. after breaking away from its mooring, hit a coral reef on March 4, 1989, and ended up spilling 117,000 gallons of Alaskan crude and bunker fuel oil, forming a two-mile slick that washed up on some Hawaiian beaches.

And continuing into the next year, on January 1 and 2, 1990, an underwater pipeline at Exxon’s giant Bayway refinery in Linden, NJ spilled 567,000 gallons of fuel oil directly into the Arthur Kill, a saltwater channel between New Jersey and Staten Island. According to NOAA, the oil blanketed more than two thousand acres of fish and wildlife habitat, including open water, tidal marshes, and backwater creeks, and over 200 acres of tidal salt marsh on Staten Island and in New Jersey. The oiling also smothered fish, crabs, and clams, and caused massive losses of salt marsh cordgrass in some wetlands. The oil also directly killed an estimated 700 waterbirds. Later in February that year, a barge spilled 25,000 gallons of oil into the Kill Van Kull waterway during a transfer from Exxon’s Bayway refinery, some of which washed up on Fire Island. But was there more to these Exxon spills than just coincidence or bad luck?

Prop-Ups & Job Cuts

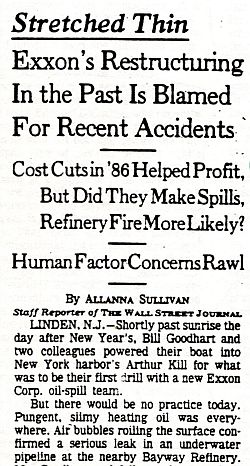

Part of a March 16, 1990 Wall Street Journal story on Exxon cost-cutting & incident risks.

By 1990, according to reporting at the time, Exxon had reduced its workforce by 28 percent, and was still cutting. But in the aftermath of its explosions and spills, some Wall Street analysts were beginning to wonder whether Exxon “may have restructured itself into trouble.”

A former Exxon employee, William Randol, told the Wall Street Journal, for example, “the system (at Exxon) is overworked and undermanned.” Other Exxon executives also confided that certain company operations were then (1990) at least 10 percent short on personnel. “We haven’t learned to play with the thinner bench,” said one.

Another Exxon refining executive, retracing the events surrounding the December 1989 Baton Rouge explosion, wondered what might have been: “If there had been enough manpower to walk those lines during the crisis (when unusual freezing temperatures hit), would the explosion have happened?” One employee in the company’s international group quit his post because he felt overworked, handling multiple jobs. “I couldn’t do my job well anymore, and that bothered me,” he explained. “I made more mistakes in the last two years than through my entire career at Exxon.”

“The heavy workloads stretch across all kinds of operations,” reported Allanna Sullivan of The Wall Street Journal in her 1990 reporting. “Some engineers assigned to maintain catalytic crackers…now tend two units rather than one. Some tankers that sailed with a crew of more than 30 before the 1986 are now sometimes manned by 21 seamen.” Exxon management claimed that gains in automation justified the personnel reductions. But others wondered if the cuts at Exxon and other oil companies may have made things worse when accidents came. By mid-1992, Exxon was among oil companies that had announced further job cuts or early retirements.

1993 Coker Blast

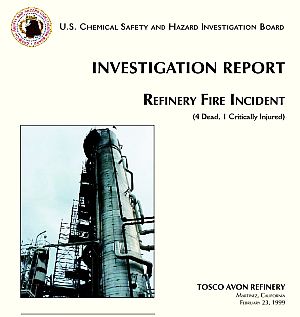

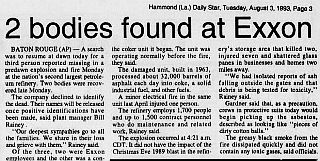

Back in Baton Rouge, meanwhile, the giant Exxon refinery and chemical complex would have additional accidents, chemical releases, and worker injuries. On August 2, 1993, at 4:21 a.m., an explosion and fire at one of the refinery’s coker units, rocked Baton Rouge again. This time, three workers were killed and the explosion and fire sent thick smoke, ash, asbestos particles and other debris into a nearby residential community.

WBRZ TV footage of 1993 fire burning at Exxon’s Baton Rouge refinery following explosion at the East Coker Unit, shown here, lower center-right with some flame visible, which sent heavy smoke & debris into residential area.

Describing the damage to the coker unit and the difficulty in locating the dead workers’ bodies following the explosion, Exxon spokesman, Walt Eldredge explained: “A lot of stuff fell or was deformed by the heat. Some of the normal access ways are not there anymore. There’s a lot of uncertain footing and it’s way up in the air.” Two of the bodies recovered were burned beyond recognition and dental records had to be used to make positive identification.

Early reporting from the Daily Star (Hammond, LA) on refinery explosions & fire at Baton Rouge on Aug 2nd, 1993, would kill 3 workers.

At the time of the explosion in 1993, this part of the Baton Rouge refinery was located directly across the street from a residential community. According to later-filed court documents, the incident’s off-site effects were described, in part, as follows: “During the two and a half hours the main fire burned, [it] produced a thick smoke plume, which moved in an easterly direction across the community adjacent to the facility… The explosion and fire also released ash and debris. The debris, including asbestos particles, was spewed from the East Coker Unit and scattered about the residential community located across the street from the refinery. The ash and debris landed on the people and property of the community.”

After the fire, Exxon crews in protective gear searched nearby neighborhood bordered by Scenic Highway [including Plank Road, Chippewa Street and Evangeline Street] for debris from the fire, some of which contained asbestos; a small amount of material was found in the area. Litigation following the 1993 explosion, brought by neighboring residents who claimed health effects, would drag out for nearly 30 years, as hearings on some claims continued at least through 2020.

1994 Associated Press story on another of Exxon’s Baton Rouge refinery explosions, this one at a chemical plant.

1994 Explosions

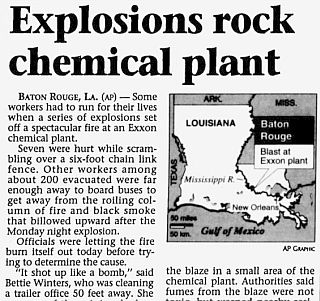

On August 8th, 1994, a three-day fire with a series of initial explosions occurred at an Exxon chemical plant located within the company’s Baton Rouge refinery site. Wit-nesses at the time reported hearing more than three explosions at the plant.

The explosions and resulting fire occurred at a steam-cracking unit where light hydrocarbons and heavy gas oils were converted into ethylene, propylene, and butadiene. An Associated Press news account noted “the explosions occurred in a furnace several stories tall when byproducts from crude oil are heated to extremely high temperatures…”

At the accident scene, the Associated Press also noted that “some workers had to run for their lives” and at least seven were injured while scrambling over a six-foot chain link fence. In all, some 200 people in the plant were evacuated from the area to get away from the fire. Some homes in a nearby residential area were then less than a half-mile from the plant. “It is a very large fire,” said spokeswoman Kay Calhoun at the time. “We have advised residents nearby to take ‘shelter in place’ by covering their windows and doors, and turning off their air conditioners.” A fire department spokeswoman at the time reported that burning petroleum products were “shooting flames into the sky,’’ causing the northbound lanes of Interstate 110 through Baton Rouge to be closed.

During the time the fire was burning, the wind carried the smoke plume to the southwest and across the Mississippi River. Exxon conducted air monitoring both inside and outside the facility, and in the surrounding community during the time of the fire. Hundreds of lawsuits were later filed alleging various health issues and other damages, but through subsequent court actions and appeals, Exxon appears to have prevailed in many of these actions, which were not resolved until about mid-2006.

As later determined, an inappropriate replacement of a failing valve with the wrong kind of valve resulted in increasing instability in the valve. The wrongly replaced valve ultimately failed, allowing hydrocarbon to spray from the tower and ignite.

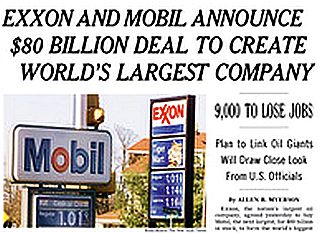

Dec 1998: Portion of New York Times front-page story on the announcement of the Exxon-Mobil merger.

Merger With Mobil

In December 1998, Exxon, then the world’s largest oil company, announced it would merge with Mobil, itself the second largest U.S. oil company.

The $82 billion deal was completed in late 1999. Exxon, in effect, was then acquiring Mobil. Their combined profits at the time were then about $12 billion annually on more than $203 billion in revenue.

Both companies were formerly part of John D, Rockefeller’s giant Standard Oil Trust, which ruled the oil business and beyond in the early 1900s until broken up in 1910 under anti-trust laws. Thereafter, Exxon and Mobil became sibling stand-alone companies for a time – Exxon, as the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey (and latter Esso), and Mobil, formerly the Standard Oil Company of New York, also known as SOCNY.

Credit card mock up showing respective company mascots – here, as if the Exxon Tiger is pursuing Mobil’s Pegasus.

The Exxon-Mobil merger, however, did not necessarily translate into safer or cleaner operations. Properties such as Mobil’s Torrance, California refinery, which had its own troubled history, would also have continued troubles as part of ExxonMobil, with a major February 2015 explosion there that would later result in the September 2015 sale of that refinery to PBF Energy. Back at Baton Rouge in subsequent years, more troubles would occur at the ExxonMobil refinery there as well.

|

2001 Overview The Baton Rouge Complex “Over the past century, ExxonMobil Baton Rouge has grown from a small refinery on 225 acres of former cotton fields to a complex of nine facilities in the Baton Rouge area,” wrote the company in 2001, describing “Who We Are” at its website. The description also included how each one of its nine parts came about, the year each was established, and the role each part played in the overall complex. The refinery, founded in 1909, is the largest component, growing to 2,100 acres on the East bank of the Mississippi River, turning out 500,000 bbls/day of crude then refined into gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, aviation fuel, lubricating oil, waxes, solvents, petroleum coke, liquified petroleum gas and chemical feedstocks. Also on the refinery grounds, founded in 1927, is the company’s Process Research Laboratories, which as of 2001, held 2,500 patents contributing to refining advances in fluid catalytic cracking, hydroprocessing, fluid coking, and catalytic reforming. The Chemical Plant, founded in 1940, and located just north of the refinery on 150 acres, turns out more than 10 billion pound of petrochemical products annually. This modern petrochemical complex uses petroleum feedstock from the refinery to make chemicals shipped out via truck, pipeline and barges to manufacturing customers that make an array of products such as paint, hoses, tires, diapers, and other products. A research center there, Intermediates Technology, was founded in 1976 Generalized Map  This somewhat simplified and generalized map shows a “wavy-lined” Mississippi River and some identified roadways running through the Baton Rouge, Louisiana ExxonMobil oil refining and petrochemical complex, along with some of its component refinery, chemical, plastics, finishing, and storage facilities as of 2001 or so. Source: ExxonMobil, “Who We Are,” and “Baton Rouge Complex on Scenic Highway,”2001. The ExxonMobil Plastic Plant, founded in 1968, is located on 60 acres near Sottlandville and Zachaery, a bit farther north of the refinery. Its production capacity is more than 900 million pounds annually, producing low density polyethylene and numerous specialty polymers, most of which is shipped out by rail. Not far away is the Baton Rouge Resins Finishing plant which “finishes” and packages resins received by pipeline from the chemical plant. As of 2001, more than 225 million pounds of “tackifying resins” were produced there each year. Also in the same area as the plastic and resins finishing plats is the Polyolefins Plant, opened in 1995 with a 1.6 billion-pound capacity, turning out high density polyethylene (HDPE). A 600-million-pound s-per-year polypropylene plant was added there some years later. Across the Mississippi, on the west bank, is the Port Allen Lubricants Plant, where 80 million gallons annually of engine oil, industrial lubricants, basestocks, process oils, grease and solvents are blended, packaged and shipped annually. Lubricant base oils, for example, are received from the refinery via pipeline, and other operations there – blending, packaging, inventory and scheduling – are coordinated by computer management systems. Also on the west bank is the Anchorage Chemical Terminal, in operation since 1972. This site provides for transportation and storage for other ExxonMobil sites. A river docking system there is designed to load ships of up to 18,000 tons with a 16-slot loading rack, allowing for the transport and storage of propylene and refined and crude butadiene. There is also the Production Gas Plant nearby and the Anchorage Tank Farm. Also part of the complex as of 2001 were: SeaRiver Maritime, a wholly owned affiliate that provides maritime transport of ExxonMobil products, and ExxonMobil Pipeline that operates in the Baton Rouge area. Source: ExxonMobil, “Who We Are,” and “Baton Rouge Complex on Scenic Highway,”2001. |

2000’s-2020’s

Recent History

What follows below are some findings and reports from government agencies such as EPA at the federal level and the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality Louisiana (LDEQ), as well as those from Louisiana environmental and community groups, the United Steelworkers union, and general news sources, on incidents that have occurred at the ExxonMobil Baton Rouge refinery and related infrastructure in more recent years.

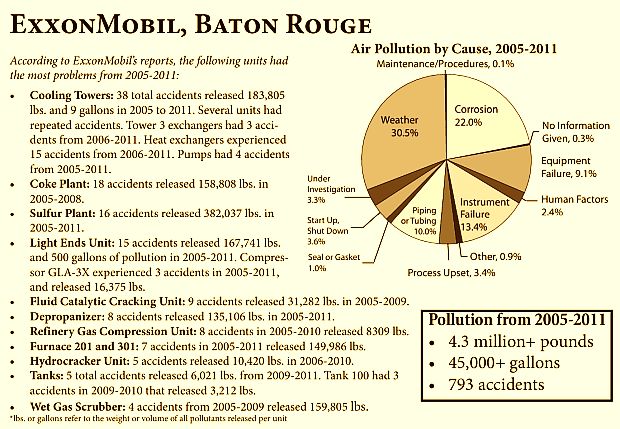

2005-2014: Accidents. The Louisiana Bucket Brigade, a public interest group based in New Orleans, has complied a 2005-2014 Louisiana Refinery Accident Database using state data for all 17 Louisiana oil refineries, consisting of accidents and pollution by year, with all reported incidents from 2005-2013, plus partial data for 2014. In that compilation, the ExxonMobil refinery at Baton Rouge topped the list with 890 total incidents occurring at that refinery during the 2005-2014 period.

“Common Ground IV” report, by Bucket Brigade & United Steelworkers, using Louisiana DEQ data, shows ExxonMobil Baton Rouge accidents & pollution during 2005-2011, both by cause & refinery unit or function. Click for report.

2010: Pipeline Leak. ExxonMobil’s Baton Rouge refinery had eight accidents in 2010 related to leaks from underground pipelines. In January 2010, ExxonMobil discovered a pipe leak of volatile chemicals to the air caused by corrosion. Further investigation determined that the pipe had actually been leaking for more than three months (since October 2009), resulting in more than 5 million pounds of volatile toxic air emissions being released – including flammable gas, propylene and volatile organic compounds. The LDEQ report for this accident indicated that the releases were classified as preventable.

2010: Flash Fire. On April 14, 2010, three workers were injured, one seriously, in a fire at the Baton Rouge refinery. One union worker, at a gas compressor, received second and third degree burns to his face, neck, hands, forearms and upper chest. Two contractors were also injured. All three were admitted to the Baton Rouge General Hospital burn unit. The cause of the incident was not initially reported. There was also a secondary explosion that occurred during a gas test on the equipment at issue, with one worker knocked off his feet, but not injured. Union officials sent a health and safety investigator to look into the incident and OSHA also began a preliminary investigation. The Steelworkers union charged that ExxonMobil, instead of focusing on process safety, based its health and safety program on a behavior-based approach called the Loss Prevention System. This approach, charged the union at the time, shifted attention away from unsafe equipment and hazardous conditions, to a focus on working safely around the hazards. No information was given regarding the root cause of the fire. This was the second of five fires that would occur at the Baton Rouge complex in 2010.

2008-2011: Air Pollution. According to data obtained from the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality through a public records request and analyzed and reported by National Public Radio in May 2013, because of accidents and leaks, from 2008 to 2011, the Exxon Mobil Baton Rouge complex released nearly 4 million additional pounds of volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, beyond allowable pollutant levels. VOCs can contribute to the formation of ground-level ozone or smog, which causes respiratory problems such as asthma attacks.

Photo of the ExxonMobil Baton Rouge, LA refinery, looking west over Mississippi River and showing portions of Standard Heights residential area in the foreground, increasingly part of a greenbelt program that Exxon initiated to buy out nearby neighbors. Photo, David Hanson, “Neighbors of the Fence,” BitterSoutherner.com, January 19, 2016.

2011: Accidents & Pollution. According to the Louisiana Bucket Brigade and United Steelworkers report on Louisiana refineries in 2011 – Common Ground IV – ExxonMobil reported the most accidents that year: 138 total accidents were reported from Exxon’s refineries at Baton Rouge (98) and Chalmette (40), resulting in a combined 428,000 pounds of pollutants released to air and over 1,274,000 gallons of pollution released to land and water.

2012: Oil Pipeline Spill. In April 2012, a major 22-inch Exxon crude oil pipeline that supplies the Baton Rouge Refinery burst, with initial reports indicting that at least 1,900 barrels of oil (80,000 gallons) had been spilled into watery tributaries in Point Coupee Parish, Louisiana. The North Line crude oil pipeline, owned by Exxon and first built in 1956, has a capacity of 160,000 barrel-per-day and originates in St. James Parish southeast of Baton Rouge. The pipeline provides shippers with access to oil from the giant Louisiana Offshore Oil Port and crude from offshore platforms. It carries crude north to Baton Rouge and a few other plants. Following the spill, clean-up operations commenced and regulators opened an investigation in response to the spill. A 17-foot rupture in the pipeline was discovered in the line about 27 miles west of Baton Rouge, near Torbert, LA, with crude spilling into the surrounding area and into a tributary connected to Bayou Cholpe. Two year later, in August 2014, the U.S. Justice Department and EPA announced that the ExxonMobil Pipeline Company agreed to pay a civil penalty for alleged violation of the Clean Water Act for the spill. Under a consent decree, ExxonMobil agreed to pay $1.4 million to resolve the government’s claim. The federal complaint also reported the spill was at least 2,800 barrels, not 1,900 as originally reported.

2014. Large storage tank at Baton Rouge refinery with painted message: “ExxonMobil and Baton Rouge - Growing Together, Working Together.” Photo, Monique Verdin, Louisiana Weekly / Louisiana Bucket Brigade.

2012: Benzene Leak. On June 14, 2012, a bleeder plug on a tank in the Baton Rouge refinery failed and began leaking naphtha, a substance composed of many chemicals including benzene. After the spill, people living in neighboring communities reported adverse health impacts such as severe headaches and respiratory difficulties. ExxonMobil originally reported to LDEQ that 1,364 pounds of material had leaked. However, several days later, on June 18th, Baton Rouge refinery representatives told the LDEQ that ExxonMobil’s chemical team determined the spill was actually “a level 2 incident,” which means a significant response to the leak was required.

A 2012 edition of Exxon's internal magazine, "The Lamp," offering a story profiling the Baton Rouge refinery.

July 2012

EPA Inspection

In July 2012, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) made a surprise inspection of the Baton Rouge refinery to see if the company was complying with the risk management prevention program required under the Clean Air Act. During four days of inspection and photographing, from July 16-July 20, 2012, EPA found some surprising failures and negligence in maintenance and safety procedures. The inspection revealed that Exxon had not examined more than 1,000 underground pipes at the refinery for five years. EPA also reported that emergency and shutdown procedures at the refinery failed to provide needed details for operators. A report on the inspection issued by EPA, later made public under a Freedom of Information Act disclosure, revealed the refinery had heavily corroded pipes and ruptured pipelines; pipes and other equipment that were overdue for internal inspection; and inadequate documentation for emergency and shutdown procedures at the refinery. Exxon’s spokesperson, Charlotte Huffaker, later told the Reuters news agency in an email that Exxon contested the violations, and that EPA withdrew all but two of its findings, which Exxon was said to have resolved.

2011 photo of a portion of the sprawling ExxonMobil complex at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where an extensive complex of pipes, tanks, and stacks need regular maintenance and inspection attention for wear-and-tear.

Still, photos from EPA’s inspection (click here for photos) showed external rust on pipes, tanks and related equipment. The United Steelworkers, reacting to the EPA report at Baton Rouge, issued a February 2013 statement noting that the EPA discoveries there were typical of others it had noted for years at other refineries and chemical plants, but also singled out ExxonMobil at Baton Rouge:

…ExxonMobil’s failure to take appropriate action on items they [EPA] identified as a concern disturbs us. Unfortunately, this is not an isolated issue but an industry-wide problem. When equipment is identified as being outside a safe operating range, it should be replaced or mitigated as soon as possible. To ignore these items should be a criminal offense because the company is knowingly placing workers and the community at risk.

Bob Landry, formerly president of United Steelworkers Local 13-12 and a 36-year employee of the company at Baton Rouge, also found that EPA’s findings were on the mark. Landry, then retired when he spoke with the Huffington Post in July 2013, commented on EPA’s findings of pipeline corrosion. “What’s more important,” he said, “is internal corrosion… “The refinery cut a lot of operations jobs in the 1990s. We thought they cut too many. The plant hasn’t had enough people since….” – Bob Landry, 2013.It’s hard to quantify the extent to which pipes at the Baton Rouge refinery are corroded and thin.”

Landry also noted Exxon job cuts as part of the safety problem. “The refinery cut a lot of operations jobs in the 1990s,” he said, during his 2013 interview. “We thought they cut too many. The plant hasn’t had enough people since. Operations are lean so ExxonMobil can save money.” Landry explained at that time that more contract workers were being hired at the Barton Rouge refinery rather that union workers – workers who are paid less than union workers and are not always as experienced or well-trained as union workers. He also pointed to an earlier May 2011 inspection at the Baton Rouge plant by the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) that had also found the refinery didn’t have enough workers for an emergency shutdown, but that “ExxonMobil appealed and OSHA dropped the charge.”

2014: LDEQ Action. A 2014 settlement agreement with Louisiana DEQ called for ExxonMobil to pay more than $2.3 million to resolve alleged permit violations over chemical releases and spills at four of its Louisiana facilities. The company agreed to pay a $300,000 civil penalty, fund more than $1 million in “beneficial environmental projects,” and spend at least $1 million on projects designed to prevent and control spills at its Baton Rouge facility. A statement issued by LDEQ said the settlement also addressed a string of alleged violations since 2008 at the Exxon Mobil refinery, a resin finishing plant, and a tank farm in West Baton Rouge Parish.

2016: LEAN Sues. In early November 2016, Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN) filed a lawsuit against ExxonMobil, claiming the chemical plant at the Baton Rouge complex continued to violate the federal Clean Air Act despite a 2014 settlement with the state. The suit alleged that pollution from the plant jeopardized the health of nearby residents of a predominantly black, low-income area. LEAN alleged the Baton Rouge refinery had violated the Clean Air Act by emitting “thousands of pounds of harmful and hazardous air pollutants above permitted limits,” while also failing to properly notify LDEQ.

November 2016

Isobutane Fire

On November 22nd, 2016, an isobutane release that ignited into a giant fireball occurred in the sulfuric acid alkylation unit at ExxonMobil’s Baton Rouge refinery. The incident occurred during minor maintenance on a flammable isobutane line which had failed. During removal of an inoperable gearbox on a plug valve, a worker removed critical bolts securing the pressure-retaining component of the valve known as the top-cap. When the worker then attempted to open the plug valve with a pipe wrench, the valve came apart and released isobutane into the unit, forming a flammable vapor cloud. The isobutane reached an ignition source within 30 seconds of the release, causing a giant fireball, severely burning four workers unable to exit the vapor cloud before it ignited.

Nov 22, 2016. Exxon Mobil Baton Rouge refinery security video captured the isobutane release and subsequent fire, shown here after about 35 seconds into the incident. Four workers there were seriously burned. Source: CSB.

Isobutane, the vapor which ignited, is a colorless liquefied petroleum gas created during oil refining and is extremely flammable. The unit where the incident occurred normally mixes isobutane with olefins and a sulfuric acid catalyst to make alkylate, a component for high octane gasoline.

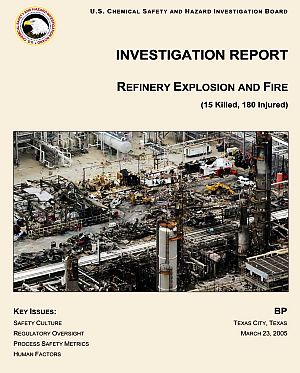

Shortly following the incident, a three-person team from the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board, commonly known as the Chemical Safety Board, or CSB, was sent to the Baton Rouge refinery to investigate the incident. The CSB is an independent, non-regulatory federal agency charged with investigating industrial chemical accidents. The agency’s board members are nominated by the president and confirmed by the U.S. Senate. CSB investigations examine all aspects of chemical accidents, including physical causes such as equipment failure or inadequacies in regulations, industry standards, and safety management systems. It does not issue citations or fines, but makes safety recommendations to companies, industry organizations, labor groups, and regulatory agencies such as OSHA and EPA. Since its creation in 1998, the CSB has consistently turned out reports known for their thoroughness and high quality. In recent years, the agency has also produced excellent video material that cover the details and causes of the accidents it investigates, such as the one below on the ExxonMobil incident at Baton Rouge:

Some months later, in September 2017, the CSB published their final report on the ExxonMobil isobutane release and fire at Baton Rouge. Among their findings were the following:

…The CSB learned that there were long-standing reliability issues with gearboxes used to operate plug valves in the refinery’s alkylation unit….

…..The CSB also learned that 15 (approximately three percent) of the roughly 500 plug valves with manually operated gearboxes in the refinery’s alkylation unit were an older design that… created the potential for incorrect removal of the gearbox, which can have catastrophic consequences…

Cover of the CSB report & safety bulletin on the ExxonMobil Baton Rouge refinery isobutane release & fire. Click for PDF.

Among “deficiencies” CSB noted in its report on the Baton Rouge incident were: “failure to identify and address the older model plug valve design and gearbox reliability; no written procedures detailing the steps needed to remove different models of gearboxes from plug valves to manually open or close the valve safely; not training workers to safely remove the various plug valve gearbox models in the alkylation unit and the hazards associated with this type of work; and, an organizational culture that accepted operators removing malfunctioning plug valve gearboxes despite the lack of detailed procedures and training for safe removal.”

The CSB’s public report on the ExxonMobil incident at Baton Rouge, was also a safety bulletin, meant to alert the industry of the equipment/technology vulnerability found with the older gearbox technologies.

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administra-tion (OSHA) also investigated the isobutane incident, and in May 2017 issued ExxonMobil nine citations over safety lapses at the plant along with proposed fines totaling $165,000. Exxon was penalized $12,675 for each serious citation, as well as $63,000 for failing to carry out external visual and ultrasonic inspections of piping. As of July 2017, TheAdvocate.com of Baton Rouge was reporting that ExxonMobil was in the process of contesting the OSHA citations.

Other Incidents. During 2017 and 2018 there were also other reported fires, chemical releases, and enforcement actions involving the ExxonMobil Baton Rouge complex. In an October 31, 2017 settlement with the U.S. EPA and Justice Department, ExxonMobil agreed to pay $2.5 million in fines for flaring gases at 8 plants along the Gulf Coast in Texas and Louisiana, including its Baton Rouge plant, and also spend $300 million to upgrade its eight petrochemical plants. Some critics felt the fine and settlement agreement was inadequate given the number of plants involved and the frequency of the flaring. ExxonMobil had reported a week earlier that it had earned $11.3 billion in the first nine months of 2017, an 84 percent increase over the same period in the prior year. Other reported incidents included a November 1st, 2017 fire that sent large plume of smoke over Baton Rouge, and another reported on August 23rd, 2018 that was contained by plant emergency workers. The day after that fire, a hydrogen chloride release occurred and workers were told to shelter-in-place.

|

Decades-Long Litigation 25 Years in Court In 2019, an old, ongoing legal battle between Exxon and Baton Rouge residents over alleged health and community damages from the 1993 Baton Rouge refinery explosion (described earlier above ), took on new life more than 25 years later after a series of appeals and a state Supreme Court ruling that allowed lower-court decisions against Exxon to stand. Following the 1993 coker explosion and fire that killed three workers and sent heavy smoke and debris into a neighboring community, litigation on behalf of thousands of nearby residents claiming damages was begun. At the time of the explosion, residents were ordered to “shelter in place” and refrain from touching any debris that might have landed on their property. First responders wearing white protective gear came into their communities to conduct testing and retrieve debris, court records indicate. In all, nearly 8,500 residents would initially sue Exxon, contending they suffered damages, claiming “personal injury, past and future pain and suffering, past and future medical expenses, mental anguish and emotional distress, damage to their homes and structures, diminution in the value of their property, other economic damages, loss of society and quality of life, loss of community, and other damages.” Initially, however, the courts dismissed the residents claims, but appeals and other legal avenues would follow. Exxon, meanwhile, had tried to shift liability for the explosion to the maker of the East Coker unit that had exploded — the Foster Wheeler Corporation. Exxon sought to recover in excess of $50 million in direct damages as well as the costs of cleaning up, rebuilding the East Coker unit, lost profits during cleanup, and loss of business opportunity due to diminished production capacity.  1990s photo of Exxon Baton Rouge refinery with 3 coker units, the size of which – for perspective – can be roughly compared to the small white truck / ambulance in the lower left foreground. Source, The Advocate newspaper. Foster Wheeler had delivered the East Coker unit to Exxon in 1963, whereupon Exxon became its owner and operator. Coker units, it turns out, are no small piece of industrial engineering, as Exxon described in its court papers. Cokers, in fact, can run to more than 300 feet in height, or about 30 stories. The East Coker Unit, for example, was one of three such units at the Baton Rouge facility. It was a typical four-drum coker unit, which contains approximately forty-one miles of pipe and tubing, and approximately ten thousand connecting elbows. The specific issue Exxon raised with the Foster Wheeler-made coker unit, however, had come down to one piece of piping made of the wrong material – a section of elbow piping. The elbow at issue was made of carbon steel instead of steel containing chromium and molybdenum, which resists corrosion from sulfur in heavy crude. It was the non-resistant carbon-steel elbow that had ruptured, causing the 1993 explosion. Therefore, Exxon believed, and argued in court, that Foster Wheeler installed the lower-grade elbow that ruptured, and should be the liable party. However, Exxon’s claim did not hold up in court, in part, because more than ten years had passed since the pipe was installed, so the designer was no longer legally liable. In court, Judge Yvette Alexander in Baton Rouge City Court ruled that Exxon accepted the East Coker Unit without inspection and placed it in operation. “From the testimony of the witnesses and experts used by Exxon and the Plaintiffs, Exxon was aware of their vulnerability as to the carbon steel elbow piping having been installed by the contractor, Foster Wheeler,” she wrote. “Exxon never corrected the serious weakness in the system nor did they require Foster Wheeler to correct it.” And later on appeal, in December 2018, the state 1st Circuit Court of Appeal also noted, that as owner of the East Coker Unit for more than 30 years, Exxon retained “ultimate responsibility” for maintaining the unit and keeping it in a reasonably safe condition. “Despite this,” the appellate court wrote, “Exxon failed to make inspections, repairs, or replacements in a reasonably prudent manner.” Meanwhile, as the initial lawsuits for damages brought by residents had failed or languished in state and federal courts, the plaintiffs turned to Baton Rouge City Court, which handles small claims. In that court, by 2014, Judge Yvette Alexander in one case, initially awarded damages to six plaintiffs – $7,500 apiece to five of the residents and $4,000 to another. Exxon then appealed. But state District Court affirmed Alexander’s decision and the awards in 2015. On further appeal, the state Supreme Court then sent the case back to the 1st Circuit that same year, and the appeals court returned it to Alexander in 2016 for, among other things, reconsideration of damage amounts. Damage amounts were then reduced in 2017 to $2,500 each for five of the plaintiffs and $1,250 for the sixth plaintiff. Exxon again appealed.As of 2020 or so, it appeared that potentially thousands of residents suing Exxon over the 1993 explosion would still have to come into court, “one by one… and plead their case before a judge and Exxon’s attorneys”… But the 1st Circuit allowed Alexander’s decision to stand, Exxon appealed again, and this time, the state Supreme Court denied Exxon’s appeal. Baton Rouge attorney, Lewis Unglesby, who represented some of the plaintiffs, would say in 2019 that the case had “gone on for too long,” and was then one of the longest civil cases ever in Baton Rouge. ”We’ve won everywhere,” he would say, citing the list of appeals in the higher courts, “and Exxon ought to be good neighbors and accept their responsibility and resolve this.” Yet, still, as of early 2020, even with the favorable ruling, it appeared that those now suing Exxon over the 1993 explosion would still have to come into the court, “one by one… and plead their case before a judge and Exxon’s attorneys,” according to Unglesby. At that rate, he believed, with potentially thousands still seeking damages, the 25 year-old case would likely drag on for many more years. ExxonMobil, meanwhile, released a January 2020 statement regarding the lawsuit, which explained in part: “ExxonMobil respectfully disagrees with the Louisiana Supreme Court’s decision not to allocate liability to another entity or require that damages be in line with prior precedent. This decision gives finality to the 6 plaintiffs whose cases were tried. Any claims of the remaining plaintiffs in the lawsuit remain to be decided upon….” |

2020

February Fire

On February 11th, 2020 just before midnight, at approximately 11:30 p.m., an explosion inside ExxonMobil’s Baton Rouge refinery turned the night sky a shade of orange and sent a large plume of smoke into the air. The fire burned for about 7 hours, until approximately 6:40 a.m. the following day.

News accounts and images of the blaze were reported by Baton Rouge WAFB-TV, CNN, CBS, as well as other regional TV reporting and various social media video posts. “The images overnight were unbelievable as fire lit up the night sky at the refinery,” said WAFB-TV news reporter, Scottie Hunter, in a February 12, 2020 report. “The massive flames and thick blanket of smoke set off panic across the Capital City. The frightening images were only outdone by the sounds those who live nearby say they heard [one resident noted hearing a series of explosions]… Despite how scary the intense flames looked, nobody was hurt and there was no immediate off-site impact.”

TV news broadcast screen-shot of ExxonMobil Baton Rouge complex ablaze during Feburary11-12, 2020 incident that shook up the city for some 7 hours before it was quelled. While tens of thousands of pounds of chemicals & vapors were released during the fire, ExxonMobil would later report that 98 percent were consumed by the fire.

ExxonMobil later stated that although tens of thousands of pounds of chemicals were released in the fire, 98 percent were consumed in the blaze. Among the chemicals released, which ExxonMobil reported to LDEQ, were the following: 62,093 pounds of flammable vapor (i.e., natural gas, which helped fuel the blaze); 35,290 pounds liquid sulfuric acid; 13,000 pounds of sulfur dioxide; 2,681 pounds of 1,3 butadiene; 33 pounds of benzene (benzene and 1,3 butadiene are known human carcinogens for long-term, chronic exposure and are also highly flammable); and five barrels of oil. All these amounts exceeded the reportable quantity threshold, but ExxonMobil said none of the 126 readings it took detected material escaping the plant. The incident also involved the release of hydrogen sulfide, but that release did not exceed the 100-pound reportable quantity threshold. Later, in restoring the unit where the fire occurred, flaring was necessitated by the “unit upset,” and that resulted in releases of sulfur dioxide that exceeded 500 pounds.

About a week after the fire, Louisiana state Senator, Cleo Fields (D-Baton Rouge), held a community meeting at Star of Bethlehem Baptist Church in Baton Rouge to discuss the February fire. Fields said he was then considering possible legislation “to ensure the safety of the state’s citizens.” During public comment at the meeting, with about 300 in attendance, some residents vented their anger and frustration with Exxon Mobil, pent up for years, over emissions, flares, fires, and safety.

February 2020. Louisiana state Senator, Cleo Fields (D-Baton Rouge), center right, at community meeting he organized at Star of Bethlehem Baptist Church in Baton Rouge to discuss the February fire at the complex. Photo, Julie Dermansky.

Although ExxonMobil had used the company’s automated dialer notification system during the incident, when approximately 1,900 calls went out to the community, some had complained of no notification. Others said they needed more detail about what was happening, and were left with little direction about what to do. The immediate panic of seeing the sky turn orange, said one resident, left many people worrying about whether they needed to get their children or elderly grandparents to safety. “Even if it’s only a possibility that releases will be made into our community,” he offered “then allow us to make a decision.”

ExxonMobil had also reported that chemicals released during the fire had been consumed in the blaze, though a number of community residents disputed that. There were also some reports that ExxonMobil workers at the meeting had been “coached” to say that chemicals had not reached residential areas. Wilma Subra, a scientist and technical consultant to LEAN, and a former MacArthur Fellow who has also served on state and federal advisory bodies, offered testimony during the meeting on chemicals that had migrated into the residential areas, reporting directly from ExxonMobil documents sent to LDEQ.

February 2020. Wilma Subra, a technical advisor to the Louisiana Environmental Action Network, reporting at the community meeting on ExxonMobil data sent to LDEQ on chemical releases from the February fire. Photo, Julie Dermansky.

One ExxonMobil Baton Rouge worker who grew up in the area and whose mother lived near the refinery, said residents needed to know the company was earnestly working for their safety. More critical was a well-known environmental advocate in the region, retired Army Lt. Gen. Russel Honoré, who was cheered for his calls for improved response time, better air monitoring, and legislative help on safety – though stressing the need “to work cooperatively” with the company.

On April 13, 2020, ExxonMobil reported that the February blaze was caused by air getting into a hydrocarbon line in a pipe rack and igniting. The resulting fire caused the pipe to leak, and that leak then affected other lines in the pipe rack. A statement at the time indicated the company would ensure the valves associated with the air getting into the line were locked in a closed position to prevent it from happening again.

Though not initially revealed, the February 2020 fire had been a serious blow to the refinery’s output, as a large crude distillation unit and a coker had been impacted. The source of the fire was a natural gas pipeline near the distillation unit. According to Reuters news reports, the fire ended up idling most of the production units at the refinery – three out of four on site.

The Ongoing Externalities

The foregoing profile of selected incidents at the ExxonMobil Baton Rouge refinery and petrochemical complex over the 1989-2020 period offers only a partial glimpse of this facility and this company’s operations and its periodic troubles. The Baton Rouge complex, of course, is only one of many ExxonMobil operations, and ExxonMobil, one part of the larger oil/petrochemical industry globally. ExxonMobil, however, is not the exception in terms of mishaps and pollution, as other oil/ petrochemical companies have similar records. And while, in recent years, the fossil fuel industry’s role in climate change has become a central concern, the “routine,” ongoing, and cumulative worker, community and environmental costs of this industry — that is, its “total incidents profile,” or “externalities” as economists call them — is considerable and mounting. From well blow-outs and tanker spills, pipeline leaks and refinery explosions, tanker truck accidents and gas station leaks, to fracking impacts and even the biological intrusions of microplastics — all are part of this industry’s external-costs ledger; costs too often borne by societies everywhere.

Back at Baton Rouge, meanwhile, ExxonMobil in 2023 completed a $230 million refinery upgrade that will, in part, enable it to use a wider range of crude oil, and also began a $500 million expansion of its chemical operations that will double production of polypropylene to 900,000 metric tons per year, aimed at meeting the growing demand for durable, high-performance plastics.

See also at this website, for example, “125 Significant Incidents,” a story profiling oil refinery performance in one year, 2012, as highlighted by the U.S. Chemical Safety Board. Also at this website, the “Environmental History” topics page includes additional story choices profiling oil and/or chemical company environmental and/or public safety history.

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing, and continued publication of this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: March 23, 2024

Last Update: March 25, 2024

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/PopHistoryDig

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Exxon At Baton Rouge: 1989-2020s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, March 23, 2024.

____________________________________

Exxon Books at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Associated Press, “One Dead As Huge Blast Rocks Exxon Oil Refinery,” The Boca Raton News (FL), December 25, 1989, p. 6-A.

Associated Press, “Blast Rocks Refinery; 1 Killed,” Chicago Tribune, December 25, 1989.

Royal Brightbill (UPI, Baton Rouge), “Exxon Storage Tanks Explode,” UPI Archives / UPI.com, December 24, 1989.

WBRZ Eyewitness TV News at 10 (ABC Baton Rouge, LA affiliate), “Exxon’s Baton Rouge, LA Refinery Explosion, December 24, 1989,” YouTube.com, Posted by jacky9br.

“Blast, Fires Wrack No. 2 U.S. Refinery,” Washington Post, December 25, 1989.

“Baton Rouge Refinery,” Wikipedia.org.

Royal Brightbill (UPI, Baton Rouge), “Worker Dies in Exxon Tanks Explosion,” UPI Archives / UPI.com, December. 25, 1989.

Associated Press, “One Worker Killed and Several Hurt in Blast at Louisiana Refinery,” New York Times, December 25, 1989.

Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN), News Archive, LeanWeb.org.

Associated Press, “Probe Begins Following La. Refinery Explosion That Burned 15 Hours,” APNewsArchive.com, December 25, 1989.

Occupational Safety and Health Adminis-tration (OSHA), U.S. Department of Labor, “Inspection Detail / Inspection: 101477560 – Exxon Company, USA / Report ID: 0625700 / Date Opened: December 26, 1989 / OSHA.gov.

Mercury News Wire Services, “2nd Body Found at Explosion Site in Baton Rouge,” San Jose Mercury News (CA), December 27, 1989, p.11-A,

“Bad Santa – Christmas 1989 Fire Hits Baton Rouge Refinery,” Industrial Fire World, Article Archives, FireWorld.com.

“Events of 1989: December 24th,” Process SafetyIntegrity.com.

Lorraine Iannello, “Exxon Puts Loss at $20 Million or less in Blast,” Journal of Commerce, December 27, 1989.

Anton Riecher and David White, “Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Dec. 24, 1989,” Industrial Fire World.com, May 4, 2020.

Chronicle Wire Services, “Tanker Hits Reef Off Oahu — 117,000 Gallons of Oil Spilled,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 4, 1989, p. A-3.

“Tanker Spills Oil Off Hawaiian Coast,” New York Times, March 4, 1989, p. 6.

Associated Press, “Oil From Grounded Tanker Hits Oahu Beaches,” Los Angeles Times, March 4, 1989.

AP, “Supreme Court — Justices Reject Exxon’s Suit, Blame It For Tanker Grounding,” Archive.SeattleTimes.com, June 10, 1996.

“Exxon Bayway: Oil Spill, Linden, New Jersey, January 1990,” NOAA.gov.

Allanna Sullivan, “Exxon’s Restructuring In the Past Is Blamed For Recent Accidents,” Wall Street Journal, March 16, 1990, p. 1.

Patrick Lee, “Exxon Trying, But Safety Record Still Weak,” The Bulletin(Oregon and L.A. Times), March 23, 1990.

Craig Wolff, “Exxon Admits a Year of Breakdowns in S.I. [Staten Island] Oil Spill,” New York Times, January 10, 1990, p. A-1.

Allan R. Gold, “Damage Seen From January Oil Spill,” New York Times, June 10, 1990, p. 32

Keith Schneider, “Chemical Plants Buy Up Neighbors for Safety Zone,” New York Times, November 28, 1990, p. 1.

“Year Later, Pipe Corrosion Cited in Blast at Exxon,” The Advocate, December 21, 1990.

“Exxon to Idle Bayway Plant Following Spills; Three Accidents Involving Spills Have Pummeled New York Area Barging Operations and Probably Will Result in Shutdown of a Refinery,” Oil & Gas Journal /OGJ.com, March 12, 1990.

Cutter Information Corp., “International Spill Statistics, 1989-1990,” Oil Spill Intelligence Report, March 28, 1991, p. 3.

Associated Press, “Three Missing in Fire,” The Day (New London, CT), August 3, 1993.

“Exxon Accidents in The Baton Rouge Area” (graphic), Baton Rouge Advocate, August 4, 1993.

Melissa Moore, “Pipe Fitting of Wrong Material Cited in Exxon Deaths,” The Advocate (Baton Rouge, LA), September 16, 1993, p. 8-B.

“Exxon Sued Over Fire,” The Oil Daily, August 4, 1994.

UPI Archives, “Chemical Plant Explodes in Louisiana,” UPI.com, August 9, 1994.

Susan Ainsworth, “Petrochemical Explosion; Exxon Blast Further Tightens Ethylene Market,” Chemical & Engineering News, August 15, 1994.

Joe Gyan, Jr., “ExxonMobil 100 Percent at Fault for Deadly 1993 Baton Rouge Refinery Fire, State High Court Says,” TheAdvocate .com, March 20, 2019.

Chris Nakamoto and Erin McWilliams, “Thousands Still Awaiting Payouts after 1993 Exxon Fire,” WBRZ.com, January 22, 2020.

“Exxon Chemical Plant 1994 Explosion,” YouTube.com (series of 1994 newscasts from WAFB-TV), posted by Louisiana Environ-mental Action Network (8:23 minutes).

“Fire at BR Exxon Plant – 1994,” YouTube .com (1994 newscast from Baton Rouge -TV, Eyewitness News, Ch. 2), posted by Louisiana Environmental Action Network (7:32 minutes).

“In re: 1994 Exxon Chemical Fire,” CaseText .com.

Anton Riecher, “Hired Gun Shootout – Louisiana Emergency Resources Supply Network Sets Nozzle Record,” Industrial Fire World, January-February 1998;

Louisiana Bucket Brigade (New Orleans, LA), “Louisiana Refinery Accident Database, 2005-2014.”

United Steelworkers, “ExxonMobil Process Safety Events, 2009-2012,” USW.org (oil bargaining / Baytown, TX), 25pp.

“Three Hurt in Baton Rouge Refinery Fire: Exxon,” Reuters.com, April 14, 2010.

Associated Press, “Refinery Fire Injures Three in Louisiana,” April 15, 2010.

United Steelworkers, Pittsburgh, PA, “Another Serious Refinery Fire Prompts USW to Renew Call for Better Process Safety,” PR Newswire, April 16, 2010.

Molly Szymanski, Anne Rolfes, Anna Hrybyk, Common Ground III: Why Cooperation to Reduce Accidents at Louisiana Refineries Is Needed Now, Louisiana Bucket Brigade (New Orleans, LA), 2010.

Region 6 News Release, “US Department of Labor’s OSHA Cites ExxonMobil Refinery in Baton Rouge, La., for Exposing Workers to Possible Fires and Explosions, Other Violations,” OSHA.gov, September 13, 2011.

“Exxon Mobil Shuts Louisiana Oil Pipeline After Leak,” Reuters.com, April 30, 2012.

Amber Stegall, “80,000 gal. Oil Spill Cleanup Continues in Pt. Coupee Parish,” WAFB.com, May. 2, 2012

Janet McGurty, “Exxon Needs U.S. Approval to Restart North Line Pipeline,” Reuters.com, May 9, 2012.

Baton Rouge Refinery Facility (BRRF), CAA §112(r) CEI Photo Log (PDF of EPA photos taken at Baton Rouge Refinery complex, July 19, 2012).

Amy Wold, “LA. DEQ Demands Timeline on Spill from ExxonMobil,” TheAdvocate.com, July 24, 2012.

J. Derek Reese, ExxonMobil Chemical Company, Baton Rouge, LA, “Unauthorized Discharge Report to the Louisiana Depart-ment of Environmental Quality (LAC 1:3925),” filed August 14, 2012, 46 pp. w/attachments.

Louisiana Bucket Brigade & United Steelworkers, Common Ground IV (Louisiana Refineries, 2005-2011), December 2012.

Sue Sturgis, “Pollution from Oil Refinery Accidents on the Rise in Louisiana,” FacingSouth.org, December 3, 2012.

Lauren McGaughy, “ExxonMobil Baton Rouge Plant Inspection Report Raises Concerns; Activists Request Full Accounting of June Benzene Spill,” NOLA.com, December 20, 2012.

“USW Says Problems EPA Found at ExxonMobil’s Baton Rouge, Louisiana Refinery are Prevalent Throughout Refining Sector,” USW.org/News (United Steelworkers, Pittsburgh, PA), February 28, 2013.

“ExxonMobil Baton Rouge Refinery Did Not Disclose Accident …,” NOLA.com, February 21, 2013.

“Plant Neighbors Complain of Ailments,” The Advocate, May 1, 2013.

“La. DEQ Demands Timeline on Spill from ExxonMobil,” The Advocate, May 2, 2013.

“DEQ Investigates Spill,” The Advocate, May 2, 2013.

Kristen Lombardi & Andrea Fuller, “’Upsets’: Chemical Releases Disrupt Lives but Rarely Result in Punishment,” NBCNews.com, May 21, 2013.

Elizabeth Shogren and Robert Benincasa, “Baton Rouge’s Corroded, Overpolluting Neighbor: Exxon Mobil,” WBUR.org/NPR, May 30, 2013.

“Criticism of ExxonMobil,” Wikipedia.org.

Susan Buchanan, “ExxonMobil is Scrutinized in Baton Rouge After Past Leaks,” HuffPost .com / Huffington Post, July 15, 2013.

Susan Buchanan, Contributor, “ExxonMobil Baton Rouge Veers Away from Unions, United Steel Workers Say,” HuffPost.com / Huffing-ton Post, July 22, 2013, (also published at The Louisiana Weekly, July 22, 2013).

“ExxonMobil Agrees to $2,329,000 Settle-ment,” DEQ.Louisiana.gov, January 10, 2014.

Press Release, Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of Justice, “ExxonMobil Pipeline Company to Pay Civil Penalty Under Proposed Settlement for Torbert, Louisiana, Oil Spill; Settlement Resolves Clean Water Act Violation Stemming from 2012 Spill,” Justice.gov, August 26, 2014.

Nick Green, “ExxonMobil Sells Torrance Refinery for More Than $530 Million,” DailyBreeze.com/The Daily Breeze (Tor-rance, CA), September 30, 2015.

David Hanson (story, photos & audio), “Neighbors of the Fence,” BitterSoutherner .com, January 19, 2016.

“LEAN sues ExxonMobil, Claiming Violations of Clean Air Act; Plant Official Claims Problems Have Been Addressed,” The Advocate, March 4, 2016.

“CSB Investigators Deploying to Fire at ExxonMobil Refinery in Baton Rouge, LA,” CSB.gov, Washington DC, November 23, 2016.

Erwin Seba, Reuters, “Louisiana Environ-mental Group Accuses Exxon-Mobil of Running ‘Poorly Maintained’ Refinery,” BusinessInsider.com, November 29, 2016.

Erwin Seba, “Exxon Mobil Fined for Louisiana Refinery Explosion That Injured Four Workers,” Reuters.com, July 13, 2017.

Bryn Stole, “ExxonMobil Fighting Citations, $165\K Fine Over Explosion That Injured 4 Workers,” TheAdvocate.com, July 18, 2017.

“CSB Releases Final Report into 2016 Refinery Fire that Seriously Injured Four Workers,” CSB.gov, September 18, 2017.

U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (CSB), Safety Bulletin, “Key Lessons from the ExxonMobil Baton Rouge Refinery Isobutane Release and Fire,” Incident Date: November 22, 2016, 4 Workers Injured, Report date, September1, 2017, 32 pp.

Lisa Friedman, “Exxon Will Pay $2.5 Million for Pollution at Gulf Coast Plants,” NYTimes.com, October 31, 2017.

“Fire Breaks Out at ExxonMobil Refinery in Baton Rouge,” CBSNews.com, November 1, 2017.

Julie Dermansky, “Exxon Refinery Catches Fire Day After Government Settles Over Pollution From Other Gulf Plants,” DeSmog.com, November 1, 2017.

“A Disaster In The Making, A New Report Documents How People Have Been Left in Harm’s Way, as the Trump Administration Attempts to Block the Chemical Disaster Rule,” EarthJustice.org, April 27, 2018.

In re: 1993 Exxon Coker Fire / M.D. Louisiana / July 17, 2008.

Karen Kidd, “ExxonMobil Remains 100 Percent Liable for Damages in 1993 East Coker Unit Fire, State Appeals Court Says,” LouisianaRecord.com, Jan 8, 2019.

Takesha Thomas, “Appeals Court Affirms Ruling Ordering ExxonMobil to Pay Residents for Damages Related to 1993 Refinery Fire,” LouisianaRecord.com, January 30, 2019.

Mark Armstrong, “ExxonMobil Denied Appeal in Explosion Lawsuit,” WBRZ.com (WBRZ TV-2 / Baton Rouge, LA), March 19, 2019.

Joe Gyan Jr. “ExxonMobil 100 Percent at Fault for Deadly 1993 Baton Rouge Refinery Fire, State High Court Says,” TheAdvocate .com, March 20, 2019.

WAFB TV-9 Staff, “Exxon Found at Fault for 1993 Deadly Explosion,” WAFB.com (Baton Rouge, LA), March 20, 2019.

David Gibson, Fixed Equipment Specialist, Sarah Whitaker, Resid Conversion Specialist, “Coke Bed Combustion Incident,” ExxonMobil Baton Rouge Refinery, May 1, 2019, PDF file.

“A Look Back: 30 Years Since Exxon Explosion in Baton Rouge,” WAFB.com (Baton Rouge, TV station), December 24, 2019.

Chris Nakamoto and Erin McWilliams, “Thousands Still Awaiting Payouts after 1993 Exxon Fire,” WBRZ.com (Baton Rouge, WBRZ-TV-2), January 22, 2020.

“Offsite Piping Fire at Exxon Baton Rouge, La. Refinery Being Contained,” Reuters.com, February 12, 2020.

Scottie Hunter, “The Investigators: Data Reveals ExxonMobil Refinery Has Faced Nearly a Dozen Documented Violations in Past Two Decades,” WAFB.com, updated: February 12, 2020.

“Explosion Rocks Oil Refinery in Baton Rouge,” WREG.com (WREG-TV, Memphis, TN), February 12, 2020.

Chris Dyer (for Dailymail.com and Reuters), “Huge Fireball Erupts over Exxon Oil Refinery in Baton Rouge, Louisiana after Explosion Sends Flames Shooting into the Night Sky,” DailyMail.com (with series of photos posted to social media), February 12, 2020.

ExxonMobil, Corporate statement, “Exxon Mobil Baton Rouge Refinery Fire Response – February 2020,” updated, February 14, 2020, 2pp.

David J. Mitchell, “ExxonMobil Fire Released Carcinogenic Chemicals, Report Says, But Monitoring Found No Local Risk,” TheAdvocate.com, February 13, 2020.

David J. Mitchell, “ExxonMobil Details Release of Chemicals in Fire but Says 98% Burned Up, Did Not Reach Community,” TheAdvocate.com, February 18, 2020.

Jacqueline Derobertis, “Community Decries ExxonMobil Safety Notification Efforts, De-mands Action and Legislation,” TheAdvocate .com, February 19, 2020.

Kristen Mosbrucker, “Notice Flaring at ExxonMobil? Baton Rouge Refinery to Restore Operations after Fire,” TheAdvocate.com, February 24, 2020.

Julie Dermansky, “Momentum Builds to Monitor Cancer Alley Air Pollution in Real Time After Exxon Refinery Fire in Louisiana,” DeSmog.com, February 24, 2020.

Ellyn Couvillion, “ExxonMobil Says Air in Line Was Cause of February Fire, Steps Taken to Prevent a Repeat,” TheAdvocate.com, April 13, 2020.

WAFB Staff, “ExxonMobil Releases Cause of Fire at Baton Rouge Refinery in February,” WAFB.com (Baton Rouge, LA, TV-9), April 13, 2020.

Jon Skolnik, “ExxonMobil Has Poured Millions into Communities It’s Accused of Poisoning. Now There’s Blowback; the Oil Giant Has Channeled Large Sums to Texas and Louisiana Refinery Towns. Activists Say That’s Not Good Enough,” Salon.com, August 25, 2021.

_______________________________________