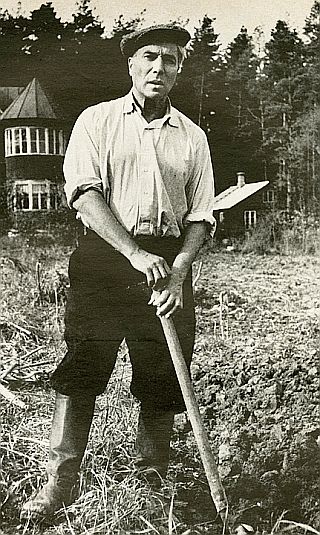

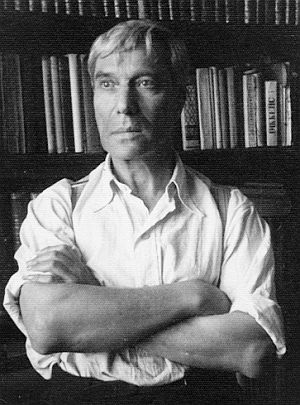

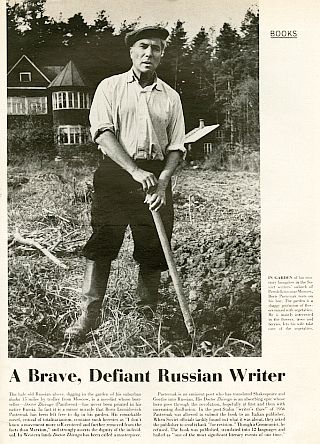

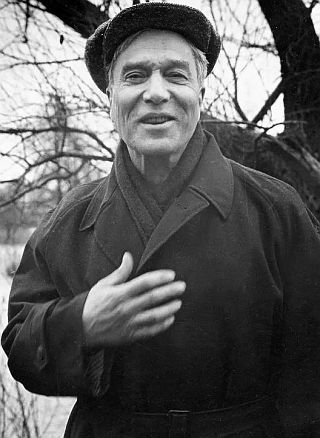

Sept 1958. Boris Pasternak, at his home in Peredelkino, Russia, working in his garden, as photographed by American, Jerry Cook for Life magazine, shortly before his Nobel Prize nomination.

Doctor Zhivago was published in 1957, but not in Russia, where it was banned for 30 years. It’s first publication in the West was not without considerable travail and courage on Pasternak’s part, given the book’s pro-individual and anti-totalitarian sentiments.

Pasternak loved his country dearly, but what he lived through and witnessed in his homeland by way of revolts, revolution, war, famine, collectivization, soviet purges, censorship, and dictatorial rule over half a century made him a staunch and unrelenting voice for freedom and the individual. And this eventually marked him as an enemy of the state, especially after his recognition in the West.

His Doctor Zhivago novel, first published in Italy and Europe, and then America, came some years after his earlier work as a poet and translator. But with its circulation and best-seller reception outside of Russia, it soon created its very own firestorm. First, some biography and background.

Boris Pasternak was born in Moscow in 1890 into a wealthy Jewish family. His father, Leonid Pasternak, was a Post-Impressionist painter and professor at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture. Some of Leonid’s illustrations appeared in Tolstoy’s 1899 novel, Resurrection. Pasternak’s mother, Rosa Kaufman, was a concert pianist and the daughter of an Odessa industrialist. Pasternak had a younger brother and two sisters, and his younger years appear to have been a good and fruitful time.

1908 - Boris Pasternak, school photo.

Pasternak, under early influence of his mother and Russian composer and pianist, Alexander Scriabin, considered a career in music, and was briefly a student at the Moscow Conservatory. However, in 1910, at the age of 20, he abruptly left for the German University of Marburg, where he would study philosophy.

In his early love life, he first fell for his cousin, Olga Freidenberg, who he’d grown up with. The two reunited in 1910, but they were never lovers. They did share a lifetime of letters, however, later published in a 1982 book. In 1912, he met Ida Wissotzkaya, from a wealthy Moscow Jewish family who then owned the world’s largest tea company. Pasternak had proposed marriage to Ida, but her family thought Pasternak a young man of poor prospects, persuading her to turn him down. A later poem, “Marburg,” recounted the rejection. But the thought of Ida would stay with him for years.

1989 edition of Boris Pasternak’s “My Sister-Life” (1922), regarded as “one of the world’s great love poems.” Univ of Minnesota Press, 103 pp. Click for recent edition at Amazon.

During World War I, he was physically disqualified for military service, having been injured in a horseback-riding accident. But during the war, at age 23, he worked for a time at a chemical factory in the Urals near Perm, Russia, during which he began gathering material he would later use in Doctor Zhivago.

In 1917, another failed love would help inspire one of Pasternak’s first popular books of poetry, My Sister, Life, which he wrote that summer but published later.

After the October Revolution of 1917, unlike his family and many of his closest friends, Pasternak chose not to leave Russia. In fact, he stayed in Moscow, and by doing so, according to one account, “was able to see the deprivations and hardships that ordinary people had to suffer under the new Red Terror.”

Max Hayward, British lecturer and famous translator of Russian literature, including Pasternak’s Zhivago, described Pasternak during those post-Revolution years as follows:

Pasternak remained in Moscow throughout the Civil War (1918–1920), making no attempt to escape abroad or to the White-occupied south, as a number of other Russian writers did at the time. No doubt, like Yuri Zhivago, he was momentarily impressed by the “splendid surgery” of the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917, but – again to judge by the evidence of the novel, and despite a personal admiration for Vladimir Lenin, whom he saw at the 9th Congress of Soviets in 1921 – he soon began to harbor profound doubts about the claims and credentials of the regime,“…[L]ike Yuri Zhivago, he was momentarily impress-ed by the ‘splendid surgery’ of the Bolshevik sei-zure of power in 1917, but… he soon began to harbor profound doubts about the claims and credentials of the regime, not to mention its style of rule…” not to mention its style of rule. The terrible shortages of food and fuel, and the depredations of the Red Terror, made life very precarious in those years, particularly for the “bourgeois” intelligentsia ….

In a letter written to Pasternak from abroad in the twenties, Marina Tsvetayeva reminded him of how she had run into him in the street in 1919 as he was on the way to sell some valuable books from his library in order to buy bread. He continued to write original work and to translate, but after about the middle of 1918 it became almost impossible to publish. The only way to make one’s work known was to declaim it in the several ‘literary’ cafes which then sprang up, or – anticipating samizdat [underground publication] – to circulate it in manuscript. It was in this way that My Sister, Life first became available to a wider audience.

By 1918, Russia’s involvement in WWI ended, and its internal civil war had begun. In July that year, Czar Nicolas II and his family were assassinated. The Russian famine of 1921-22, which came with the disruptions of the Russian Revolution and Civil War, killed an estimated 5 million people, with some reports of cannibalism.

Later photo of Pasternak with first wife, Evgenia, and son, Yvgeny.

Pasternak had also published other work by then, including his first prose work, The Childhood of Luvers, a depiction of a young girl on the threshold of womanhood, and Themes and Variations, in 1923.

In January 1924, Lenin died and Joseph Stalin assumed leadership over the country and would begin consolidating his power. The government by then controlled most publishing, and Pasternak was feeling increasing pressure to conform to Party ideals in his work. That year, however, he published Sublime Malady, which portrayed the earlier 1905 Russian revolt as he saw it.

1924. Boris Pasternak (second from left) with friends including Lilya Brik, Sergei Eisenstein (third from left) and Vladimir Mayakovsky (center). On the far left, Japanese writer Tomizi Tamiji Naito (1885-1965). From the Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1924

In 1925, Pasternak published Aerial Ways, a collection of four short stories. The earlier Russian Revolt of 1905 was again a subject of continuing interest to Pasternak, as he used it in two published poems in 1927 – Lieutenant Schmidt, a sorrowful treatment for the fate of Lieutenant Schmidt, the leader of a mutiny at Sevastopol, and The Year 1905, described by one account as “a powerful but diffuse poem” on events related to the 1905 revolt.

By 1927, Pasternak was at odds with the views of some his close friends, including Vladimir Mayakovsky, when they advocated the subordination of the arts to the needs of the Communist Party.

Later 1959 paperback edition of Pasternak’s 1931 work, “Safe Conduct,” autobiography with poems & short stories. Click for Amazon.

In the early 1930s, Pasternak was also purposely reshaping his style to make his works more accessible to the general public, printing in 1932, for example, a new collection of poems titled, The Second Birth.

In 1932, Pasternak fell in love with Zinaida Neuhaus, the wife of the Russian pianist Heinrich Neuhaus. They both then divorced their respective partners, married two years later, and would have a son, Leonid.

The Stalin Cult

Meanwhile, as Joseph Stalin rose in stature in the Soviet government, a personality cult emerged around him in Russian society (from 1929 through the rest of Stalin’s rule, the Soviet press presented Stalin as an all-powerful, all-knowing leader, with his name and image appearing everywhere), and some writers and poets initially praised him.

Pasternak, too, was initially supportive of Stalin, as the two entered into a bit of dialogue.

Pasternak wrote several letters to the Soviet leader, including a private letter in 1932 to offer his condolences at the death of Stalin’s second wife, Nadezhda Alliluyeva.

Joseph Stalin, official portrait, 1942.

On the night of May 14th 1934, Mandelstam was arrested at his home. Learning of the arrest, Pasternak then went to the offices of the Russian newspaper, Izvestia, and urged Nikolai Bukharin, a prominent politician, author, and party official, to intercede on Mandelstam’s behalf. Soon after his meeting with Bukharin, the telephone rang in Pasternak’s Moscow apartment, and at the other end of the line was Joseph Stalin himself, which caught Pasternak somewhat off guard, with Stalin asking him what was being said about Mandelstam’s arrest, and taunting Pasternak about his personal loyalty to a friend – with Stalin then hanging up.

In the fall of 1935, Pasternak would address another letter to Stalin, asking him to free the husband (Nikolai Punin) and son, (Lev Gumilyov) of famous Russian poet, Anna Akhmatova, who were accused of terrorist activities. Stalin released them at the time (although both would later spend many years in the Gulag, where Punin died), bringing a thank you letter from Pasternak along with a collection of Georgian poets’ translations he had made (Stalin had dabbled in poetry himself as a younger man).

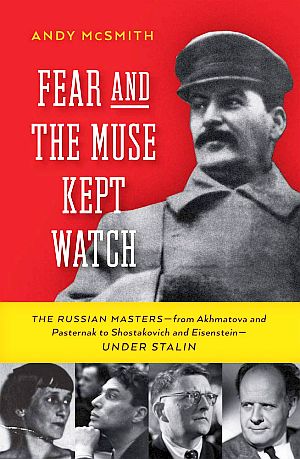

For more on Stalin & the arts see, Andy McSmith’s 2015 book, “Fear and the Muse Kept Watch: The Russian Masters from Akhmatova and Pasternak to Shostakovich and Eisenstein Under Stalin.” The New Press, 416 pp. Click for Amazon.

The Great Purge

During a 1937 Soviet “show trial” of two suspect military generals, the Union of Soviet Writers requested all of its members to add their names to a statement supporting the death penalty for the defendants. Pasternak refused to sign, even after Union leadership had visited and threatened him. Pasternak then appealed directly to Stalin, describing his family’s strong Tolstoyan (Christian) convictions, and that he could not stand as a self-appointed judge of life and death. And for this, Pasternak was certain he would be arrested. Instead, Stalin is said to have crossed Pasternak’s name off an execution list, reportedly declaring, “Do not touch this cloud dweller,” or, in another translation, “Leave that holy fool alone!”

The total estimate of deaths brought about by Soviet repression during the Great Purge (roughly 1936-1940) ranges from 950,000 to 1.2 million, which includes executions, deaths in detention and those who died shortly after being released from the Gulag,

As for Pasternak, little original poetry or prose was produced in the late 1930s, as he turned his attention to translations. In the press, meanwhile, Pasternak received increasing criticism.

World War II

1943. Pasternak, left, on a writers’ delegation to the Orel battlefield front during WWII with a war correspondent.

When Germany began bombing Moscow, Pasternak served as a fire warden on the roof of the writer’s building, and according to later accounts, repeatedly helped dispose of German bombs which fell there. Pasternak, family members, and some fellow writers, were later evacuated from Moscow.

Boris Pasternak in his study, early 1950s.

Of the war’s aftermath, Pasternak later said:

“If, in a bad dream, we had seen all the horrors in store for us after the war, we should not have been sorry to see Stalin fall, together with Hitler. Then, an end to the war in favor of our allies, civilized countries with democratic traditions, would have meant a hundred times less suffering for our people than that which Stalin again inflicted on it after his victory.”

By 1943 Pasternak and wife Zinaida had returned to Moscow. That year, Early Trains, a collection of earlier poems was published, and later, another collection in 1945. But during the mid-1940s, Pasternak was working mainly on Shakespeare translations – among them, “Antony & Cleopatra,” “Romeo & Juliet,” “1-2 Henry IV” and “Othello.”

Olga, Boris & Zhivago

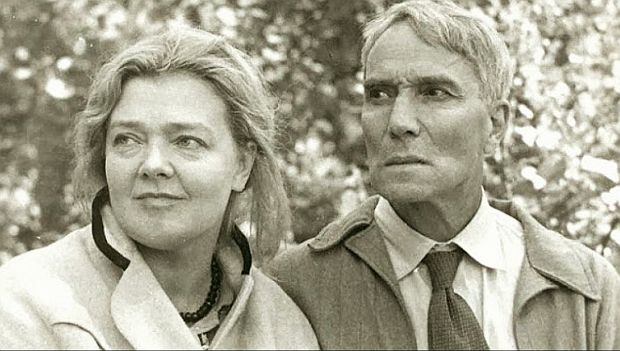

In 1946 Pasternak, then in his mid-50s, met and fell in love with Olga Ivinskaya, a 34 year-old single mother and editorial assistant for the Soviet monthly periodical, Novy Mir. They began an affair a year later in 1947. Ivinskaya is thought to be the inspiration for Lara in Doctor Zhivago. Pasternak had started work on Zhivago years earlier, but mostly in fragments.

Boris Pasternak with Olga Ivinskaya, who became his life-long lover in 1947, and is believed to have been the inspiration and model for the Lara character in his famous novel, “Doctor Zhivago.” Photo is believed to be from late 1950s.

Although his relationship with Olga Ivinskaya would last for the remainder of Pasternak’s life, he never formally left his second wife, Zinaida.

In Russia, meanwhile, by 1946 communist rule had moved to bring the arts more completely under Party control, and away from Western influence. That year, the Zhdanov Doctrine was put into effect, developed by Central Committee secretary, Andrei Zhdanov, whereby Soviet artists, writers and intelligentsia had to conform to the party line in their creative works. Artists who failed to do so risked persecution – termed “Zhdanov repression” by some. The policy remained in effect until the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953. But in 1946, Akhmatova ans Zoshchenko, a satirist, was accused of “bourgeois individualism” by the Central Committee of Communist Party, and Pasternak refused to condemn him. Pasternak was also named in a critical speech by Fadeyev, Secretary of Writers’ Union. However, Pasternak by this date was getting notice for his work abroad. Still, at home, during 1947-1949, Pasternak continued to be attacked by the Writer’s Union.

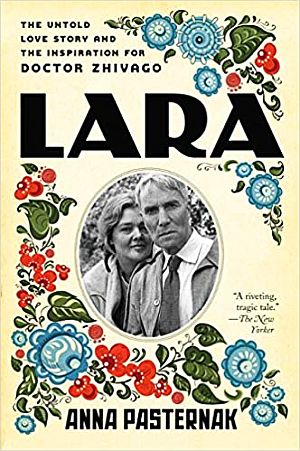

In 2017, Anna Pasternak, great niece of Boris, published “Lara,” which covers the affair between her uncle and Olga Ivinskaya, the inspiration for the Lara character in “Doctor Zhivago.” Click for copy.

Ivinskaya was sentenced to five years in prison in what was seen as an attempt by the government to pressure Pasternak to give up his writing critical of the Soviet system.

Pasternak, in a later correspondence to a friend, noted Olga’s sacrifice on his behalf: “She was put in jail on my account, as the person considered by the secret police to be closest to me, and they hoped that by means of a grueling interrogation and threats they could extract enough evidence from her to put me on trial. I owe my life, and the fact that they did not touch me in those years, to her heroism and endurance.”

Olga had refused to incriminate Pasternak, and when arrested, she was pregnant with his child, though miscarried while in prison.

Stalin died in 1953 at which time Olga Ivinskaya was still in a gulag while Pasternak remained in Moscow. She was released shortly after Stalin’s death and the relationship between she and Pasternak then continued.

In 1956, during Nikita Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization “thaw,” Pasternak submitted his manuscript of Doctor Zhivago to Novy Mir for publication, and it appeared the book was on track to be published in Russia. But at the time, Soviet party politics and philosophy were in flux, as Khrushchev had differences with Stalinism, and this, among other factors, caused the Russian version of Zhivago to be stopped. Novy Mir later rejected the manuscript, demanding extensive revision and cutting due to its “spirit. . .of non-acceptance of the socialist revolution,” as well as Pasternak’s criticisms of Stalinism, Collectivization, the Great Purge, and the Gulag. But in the interim, another opportunity had presented itself.

The Italian Option

Cover of November 1957 Italian version of “Doctor Zhivago” published by Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, the first to publish the book. Click for U.S. Pantheon edition w/similar cover.

Upon learning of Doctor Zhivago‘s existence, D’Angelo traveled to Peredelkino to meet with Pasternak and offered to submit Pasternak’s Zhivago novel to Feltrinelli for publishing in Italy. By one account, Pasternak was at first stunned by the offer, then emerged from his study with a copy of the manuscript for D’Angelo.

Pasternak knew he was taking a risk in doing so, reportedly saying to D’Angelo at the time, “You are hereby invited to watch me face the firing squad.” And with that, the Zhivago manuscript was then smuggled out of Russia to Italy.

In June 1956, Pasternak signed a contract with Feltrinelli for the Italian publication of Zhivago. In September, Novy Mir refused publication of Doctor Zhivago.

According to one account, the Soviet government then forced Pasternak to cable the Italian publisher to withdraw the manuscript, but Pasternak also sent separate, secret letters advising Feltrinelli to ignore the telegrams. Despite the Soviet objections, plus appeals to the Italian publisher by the Union of Soviet Writers to prevent its publication, Feltrinelli went ahead with his plans and published an Italian translation of Doctor Zhivago in November 1957 (and for this, he was ousted from the Italian Communist party). He also had obtained translation rights for 18 other languages. A French translation was published in June 1958. Then came English translations in September 1958. In the U.S., Pantheon Books in New York would publish Doctor Zhivago in hardback edition that fall.

Pasternak News

But in advance of the U.S. publication, there had been running New York Times stories and other news reporting on the perils that Boris Pasternak and his Doctor Zhivago novel were facing in Russia. These stories began appearing in late November 1957 and continued through Doctor Zhivago’s U.S. publication, Pasternak’s Nobel Prize nomination of October 1958, and the controversy that followed, as Soviet authorities moved to discredit the book and author.

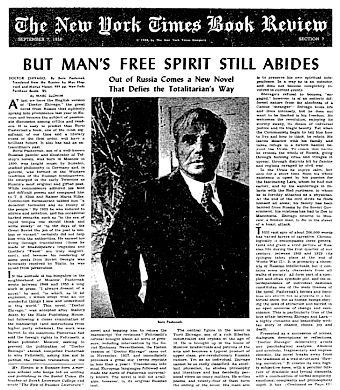

September 7th, 1958. The New York Times Book Review put the review of the first U.S. edition of “Doctor Zhivago” on its front page.

On November 21, 1957, the New York Times ran a story on page 15 with this headline: “New Soviet Novel Appears in West; Italy Publishing Pasternak Work That Moscow Tried to Hold Up for Revision.”

About a month later, on December 17, 1957, a Max Frankel story in the New York Times, based on an interview with Pasternak, ran on page 22 with this headline: “Russian Regrets Storm Over Book; Pasternak, Interview, Says Novel Barred by Moscow Reflects Trend of Times.”

Then in the following year, came the first reviews of the book’s publication in the U.S., which sent the Soviet establishment into a campaign to discredit the book and author.

On September 7, 1958, The New York Times Book Review featured a review of Doctor Zhivago on its front page along with a photo of Pasternak, using the headlines: “But Man’s Free Spirit Still Abides” and, “Out of Russian Comes A New Novel That Defies The Totalitarian’s Way.”

The review, by literary critic Marc Slonim, was highly praiseworthy, noting . “..It is easy to predict that Boris Pasternak’s book, one of the most significant of our time and a literary event of the first order, will have a brilliant future…”

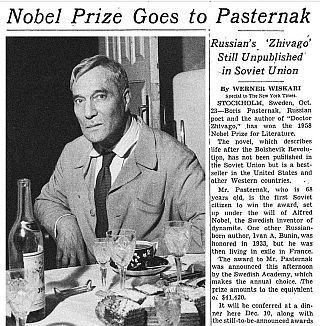

Oct 24 1958 New York Times front-page story: “Nobel Prize Goes to Pasternak; Russian's 'Zhivago' Still Unpublished in Soviet Union.”

On October 25th, 1958, Pasternak sent a telegram replying to the Swedish Academy: “Infinitely grateful, touched, proud, surprised, overwhelmed.”

But not long thereafter, Soviet authorities soon went into attack mode on Pasternak and his novel.

A day later, a New York Times front-page story used the headline, “Soviet Calls Nobel Award To Pasternak a Hostile Act,” while also noting the book had not been published in Russia.

An editorial in Pravda of October 25th, 1958 assailed Pasternak, calling him a “malevolent Philistine,” a “libeler” and “an extraneous smudge in our Socialist country.” In the same piece, his novel was dismissed as “malicious,” a “low-grade reactionary hackwork” and “political slander.”

The next day, other Soviet newspapers also began denouncing Pasternak, calling his book an “artistically squalid, malicious work replete with hatred of Socialism.”

Oct 27, 1958 story in Life magazine on Pasternak in front of his home with headline, “A Brave, Defiant Russian Writer.” Jerry Cook, photo. Filed before Nobel news.

The Life story noted, in part, “it is a minor miracle” that Pasternak “has been left free to dig in his garden,” as his “remarkable novel, critical of totalitarianism, contains such heresies as ‘I don’t know a movement more self-centered and further removed from the facts than Marxism’.”

Back in Russia, meanwhile, the attacks on Pasternak continued. By October 28th, 1958, the Soviet Writers Union had moved to expel Pasternak, calling him “a pawn in the Cold War.”

A day later Pasternak wrote to the Noble committee in Sweden saying he could not accept the Nobel Prize. In this second telegram to the Nobel Committee, he wrote: “In view of the meaning given the award by the society in which I live, I must renounce this undeserved distinction which has been conferred on me. Please do not take my voluntary renunciation amiss.”

A subsequent announcement by the Swedish Academy noted: “This refusal, of course, in no way alters the validity of the award. There remains only for the Academy, however, to announce with regret that the presentation of the Prize cannot take place.”

The Soviets interpreted the award as being given expressly for Doctor Zhivago, which by then, they had banned due to its “spirit. . . of non-acceptance of the socialist revolution.”

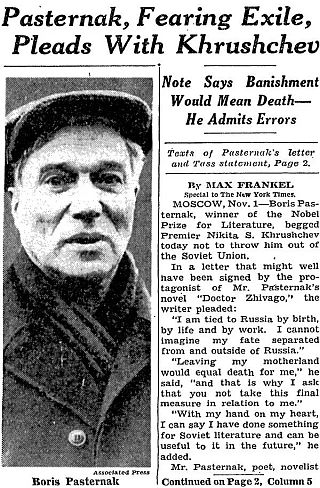

Front-page New York Times story of November 2, 1958 reporting on Pasternak’s letter to Nikita Khrushchev.

The Moscow section of the Soviet Union of Writers had then petitioned the Government to strip “the traitor Pasternak” of his citizenship and expel him from the country. This appeared to be part pf a determined campaign designed to drive Pasternak from his native land.

Pasternak, meanwhile, loved his country dearly and wanted to stay in his homeland. On November 1st, 1958 he wrote to Khrushchev seeking to remain in the Soviet Union, “Leaving the motherland will equal death for me,” he wrote. In his letter, he admitted that he had made errors, but….

Doctor Zhivago, meanwhile, reached No. 1 on the New York Times bestseller list in November 1958.

A few days later on November 3, 1958, it was reported that that Pasternak was ill, according to his wife, and that he needed to rest and be free of interviews.

However, on November 6, 1958, in a letter to Pravda that sounded like it was written by Soviet authorities, Pasternak issued a public apology saying that he erred in hailing the “political” Nobel Prize, regretted the effect his book was having, and had been “mistaken” in his earlier welcoming of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

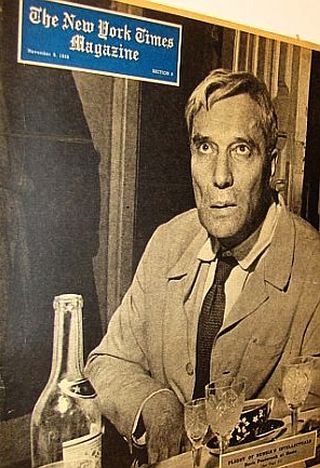

Nov 9, 1958. Boris Pasternak featured on the cover of New York Times Magazine for story, “Nikita Khrushchev and 'Doctor Zhivago’.”

More Notice

But in the West, largely because he had been singled out for the Nobel Prize, Pasternak and his book continued to receive high praise and visibility. And for sure, aside from Pasternak’s talents and deserved kudos, the whole affair was tangled up with Cold War politics.

The New York Times Magazine, of November 9th, 1958 featured Pasternak on its cover seated at a table at his home, with a feature story by historian, James Billington.

That story included the tagline: “Nikita Khrushchev and ‘Doctor Zhivago’. The Paster-nak Case Underlines Moscow’s Dilemma: To Give Intellectuals Freedom to Produce What the Regime Needs — And Yet to Keep Them on a Strong Leash.” In that piece, Billington would further explain:

…The current Soviet campaign to humiliate and defame Boris Pasternak is only the latest and most dramatic illustration of the continuing tension between the Soviet regime and its intellectuals. Whatever Khrushchev’s successes in material construction and foreign policy, he has not yet found a formula for dealing with this troublesome element in Soviet society….

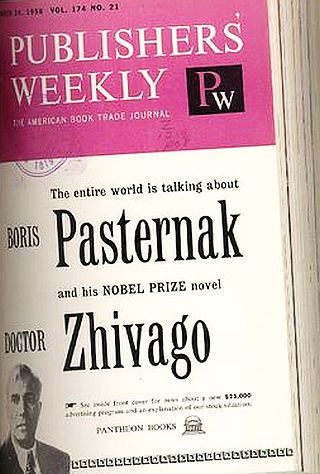

In the publishing trade press, meanwhile, Pasternak and Doctor Zhivago were featured on the November 24th, 1958 front cover of Publisher’s Weekly – a key player in the publishing world.

Nov 24, 1958. Front cover of Publisher’s Weekly features Pasternak & ‘Zhivago’ in pitch by publisher, Pantheon Books.

Kirkus Reviews, another trade publishing bellwether, in an earlier August 15th, 1958 review, called the book, “Absolutely a must for the literati.” And the Saturday Review of September 6th, 1958 spared no adjectives in its praiseworthy review: “Like all great works, ‘Doctor Zhivago’ stands alone, unique in concept, poetic in execution, devastating in power, suffused in delicately mystical philosophy, deeply tender in romance, nakedly surgical in its dissection of political folly, and honest in its conviction that man is a simple, if noble, figure in a complex cosmos.”

Notable literary critic and author, Edmund Wilson, in his November 1958 review of the book for The New Yorker, while noting some stylistic issues, nonetheless praised the novel as “one of the very great books of our time,” concluding: “Doctor Zhivago’ will, I believe, come to stand as one of the great events in man’s literary and moral history.”

In Sweden, meanwhile, on December 10th, 1958, at the Nobel Prize awards ceremony at Stockholm’s concert hall, Boris Pasternak, although absent, was honored nonetheless, along with seven other laureates who attended the ceremony, with officials reiterating that Pasternak’s award was still valid. As the New York Times reported: “Pasternak’s $41,420 award, his heavy gold medal and leather-bound scroll are being held in trust for him in case he may some day have a chance to accept them.”

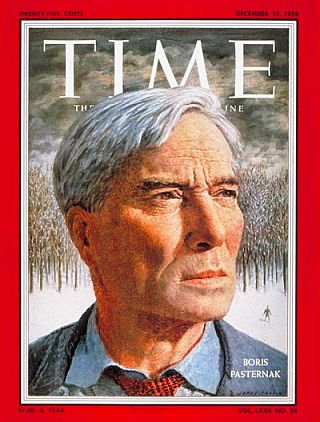

“Doctor Zhivago” author, Boris Pasternak, on Time’s cover, December 15, 1958.

… a historical novel of ‘Russia’s terrible years,’ bearing witness to the sufferings of the Russian people. It is also a novel of Christian humanism that opposes the materialism of both East and West, affirms the sanctity of every man’s soul under God. It is a novel in praise of the continuity of life, which for Pasternak means resurrection. It is, finally, a novel dedicated to the primacy of the individual and his private life in defiance of superstates, of groupthink, of social and ideological regimentation…

Pasternak’s novel, said Time, “flatly pits the individual against ‘adjustment to the group,’ the soul’s need against economic need, the organic against the mechanical.”

As for the novel’s construction, there were some shortcomings, according to Time, in both style and structure.

But “what raises Zhivago above technically better-made novels,” said Time, “is that it is charged with moral passion” And of Pasternak himself, Time concluded, his “undiminished confidence in the future of humanity is perhaps his greatest gift of all.”

Book sales, meanwhile, according to Publisher’s Weekly data as of December 29th, 1958, was one indication of Pasternak’s appeal. Doctor Zhivago in the preceding week was selling an average of 10,000 copies per day. The book had risen to No. 1 on the Publisher’s Weekly bestsellers chart as of November 24th, 1958. And it would stay there for next five months or more.

In 1959, Pasternak returned to his writing, publishing When the Weather Clears, and a second autobiographical work, titled, An Essay in Autobiography, published by Pantheon as, I Remember: Sketch for An Autobiography.However, on February 11th, 1959, a poem by Pasternak titled, “The Nobel Prize,” was published in London’s Daily Mail newspaper, which angered Soviet authorities. Shortly afterward, in a mid-February 1959 interview, Pasternak made some remarks about his novel, Doctor Zhivago, noting that he would not retract a single word of the best-selling book, and that he was “grateful in my heart that the world is reading it.” These views came from an interview he had at Peredelkino with Scripps-Howard reporter, Henry Taylor, and were printed in the New York World-Telegram & Sun. In that interview, Pasternak also explained: “Doctor Zhivago was not a political book. But in the eyes of the Soviet state, a nonpolitical book becomes negatively political. It is charged that the Nobel Committee made a political decision. But I honestly believe they were judging the work of a man’s life.”

A few weeks later, on March 14, 1959, Pasternak was interrogated by R. Rudenko, the Public Prosecutor of the Soviet Union, and was accused of crimes against the state.

Pasternak’s personal health by this time wasn’t the best. He had suffered a heart attack in October 1952, and was in the hospital for three months until January 1953. In March 1957 he was hospitalized again, and a third time during February-April 1958.

Journalists from the West, meanwhile, would occasionally set out for Peredelkino to interview Pasternak. Among those who managed to see him was Jahn Robbins, a journalist of the Quaker persuasion, who was surprised to land a four-hour session with Pasternak in September 1959, during which the author and poet held forth on religion, worker dignity, patriotism, and more. One comment Pasternak left with Robbins was the following observation about those reading his book:While Soviet authorities sought to ignore the death of Boris Pasternak and discouraged notice of his funeral, some 1,500 admirers still came to Peredelkino to pay their respects and read his poetry. “Do people buy Doctor Zhivago because it is a good book or only because they think it is anti-Communist?,” he asked, then adding quickly, “No one has understood Dr. Zhivago [the character]. He is a literary victim of the cold war. Every country, whether Communist or not communist, has its quota of Dr. Zhivagos.” Then he said, as if admonishing all those possibly missing that point, “Read it again and try to see it that way.”

In February 1960, Boris Pasternak celebrated his 70th birthday, with letters and congratulation from all over the world. However, in April that year, he became ill with cancer and died at his home in Peredelkino on May 30th, 1960.

Although announcement of his death was low-keyed by Soviet authorities, word got out about his funeral in Moscow’s underground press, and thousands showed up at Peredelkino for his funeral, where some in attendance read his poetry or otherwise made statements about the importance of his works.

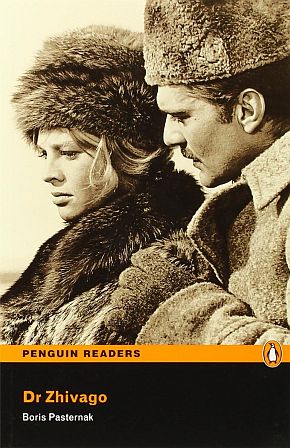

The scene at his funeral, in fact, was similar, in part, to that portrayed for Yuri Zhivago in the 1965 “Doctor Zhivago” Hollywood film — a scene in which long lines of admirers were shown filing past his gravesite. In fact, the Oscar- and award-winning “Doctor Zhivago” film – starring Omar Sharif and Julie Christie, directed by David Lean – in addition to being a worldwide box-office success, helped renew interest in both the Doctor Zhivago novel and Boris Pasternak through the 1960s and beyond (see Doctor Zhivago film story at this website for more on the film). The film also helped sell more Doctor Zhivago novels and other Pasternak works. Even through the early 2000s, paperback editions of the Doctor Zhivago novel used screen shots or poster art from the 1965 film as the book’s cover.

1972 Fontana paperback cover for Doctor Zhivago uses Moscow massacre scene from 1965 Zhivago film. |

2008 Penguin paperback cover for Doctor Zhivago uses Omar Sharif-Julie Christie scene from 1965 film. |

Continuing Story

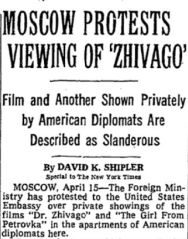

April 16th, 1977. New York Times.

In April 1977, for example, Russia’s Foreign Ministry lodged a protest with the U.S. Embassy in Moscow over private showings of the films “Dr. Zhivago” and “The Girl From Petrovka” in the apartments of American diplomats, which also included some Soviet citizens.

The film showings were described as “frankly provocative and not helpful to Soviet-American relations” in a protest note handed to William Brown, political counselor at the embassy. The Soviet Foreign Ministry charged that the films “crudely falsify Soviet history and represent the life of the Soviet people in a tendentious and slanderous manner.”

As of 1977, there were more than 5 million total copies of Doctor Zhivago sold throughout the world, though still not published in Russia. Nor was the 1965 “Doctor Zhivago” Hollywood film publicly shown in Russia, banned in theaters there until 1994.

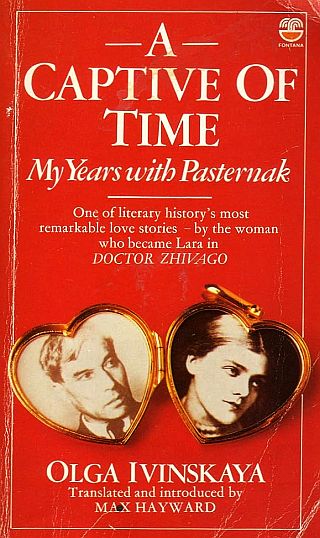

In early 1978, a major Pasternak-Zhivago story emerged with the memoir of Pasternak’s lover, Olga Ivinskaya, the model for Zhivago’s Lara.

Paperback edition of Olga Ivinskaya’s 1978 book, “A Captive of Time : My Years with Pasternak.” Click for Amazon.

Ivinskaya, in fact, had been arrested for a second time shortly after Pasternak’s death in 1960, her apartment ransacked, and her Pasternak letters and other materials confiscated.

This time, she was arrested on a trumped-up charge of currency speculation, sentenced in November 1960 to eight years in a Siberian labor camp, and treated harshly there.

Shortly before his death, Pasternak had arranged with the Italian publisher of Doctor Zhivago to send some of the book’s royalties to Ivinskaya to help with her support and that of her daughter, Irina.

Soviet authorities cited this transfer as a violation of law and sentenced both Ivinskaya and Irina, to prison. Ivinskaya’s health deteriorated during her time in the Gulag, and her imprisonment became a matter of protest in the West, with appeals from Eleanor Roosevelt, Nehru, Bertrand Russell and others – appeals unanswered by Soviet authorities.

However, some years later, in November 1964, Ivinskaya was released after serving four years of her sentence. Her daughter, Irina, released earlier, in June 1962, having served half of a three-year term.

Still, Ivinskaya would not be fully “rehabilitated” in Soviet terms, until Mikhail Gorbachev’s more liberal administration emerged in 1988

But for years after her release from the Gulag, Ivinskaya would continue to battle with Soviet authorities over her confiscated letters and papers. She would also be blocked in some of these fights by other Pasternak heirs, with some of those battles in protracted court proceedings. But her 1978 book, at least, helped tell her story — as well as revealing and/or corroborating details about Pasternak.

Ivinskaya began work on her book after release from the Gulag in the mid-1960s, completing it in 1972. It was published in London by Collins and Harvill Press in 1978 and also by Doubleday in the U.S..

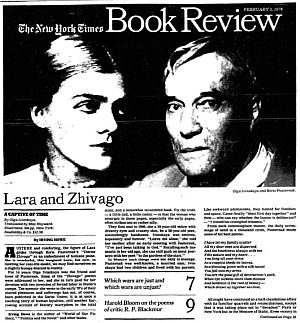

Olga Ivinskaya’s 1978 book, “A Captive in Time: My Years With Boris Pasternak,” NYT Book Review, p. 1.

And Ivinskaya was there for all of it – helping prepare the manuscript, dealing with publishers, the Soviet authorities, and the outside world, continuing through the Nobel Prize controversy and Pasternak’s death.

Her book received front-page treatment at The New York Times Book Review; featured on the cover of the February 5th, 1978 edition, with a long review titled “Lara and Zhivago” by noted author Irving Howe. Howe called the book, “at once a touching story of human loyalties, [and] still another harrowing account of literary martyrdom in the total state…” At the end of his review, which is also, in part, a review of the merits and flaws of Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, Howe says of Ivinskaya: “When he made this woman the model of Lara, Pasternak knew what he was doing, for he meant to celebrate the indestructibility of good feeling, of friendship and affection, as against the death-claw of the total state…”. In September 1995, Olga Ivinskaya died in Moscow at age 83.

The 1980s

October 1981. “Boris Pasternak: His Life and Art,” a biography by Guy de Mallac, University of Oklahoma Press, Click for copy.

According to the book’s publisher: “De Mallac has carefully pieced together a coherent narrative of the whole of Pasternak’s life, based on the internal evidence of his works, obscure published and unpublished materials, and the personal recollections of Pasternak’s surviving relatives and friends in Russia and the West.”

“…. For the scholar, this volume offers much new insights into Pasternak the man and artist; for the student of Russian literature, the most thoroughgoing critical examination available; and for the general reader, the panorama not only of Pasternak’s life but also of literary and historical twentieth century Russia…”

Another revealing book on the life and writing of Boris Pasternak appearing in the early 1980s came with the publication of The Correspondence of Boris Pasternak and Olga Freidenberg 1910-1954. Compiled and edited and translated by Elliott Mossman (with Margaret Wettlin) it was published in 1982 by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

1982, “The Correspondence of Boris Pasternak and Olga Freidenberg 1910-1954,” compiled and edited, by Elliott Mossman. Click for Amazon.

Their correspondence began in the spring of 1910, when they were 20, and continued for over 40 years, with their letters, “helping, encouraging and inspiring each other…”

In her June 1982 review of the book, which appeared on the front page of the New York Times Book Review, Helen Muchnic, professor emeritus of Russian literature at Smith College and author of From Gorky to Pasternak, called the collection, “a historical and literary document of the first importance.”

Like Pasternak, Olga Freidenberg became critical of the Russian government. “’In our country,” she would write at one point, “Marxism is neither a philosophy nor a scientific method. It is a bludgeon. It falls into the category of police power.” In her career, Freidenberg entered the University of St. Petersburg and became a scholar in the fields of semantics, folklore and Greek literature. By 1932 she organized the newly-formed Leningrad Institute of Philosophy, Language, Literature and History; obtained a doctoral degree, lectured, and had devoted students.

Gorbachev Reforms

In Russia, meanwhile, by 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev had become First Secretary of The Communist Party and a move toward a more liberal Soviet Union was soon to come, with new freedoms and greater openness in government affairs, the press, political debate, and Soviet culture – including, it turned out, for Boris Pasternak and Doctor Zhivago.

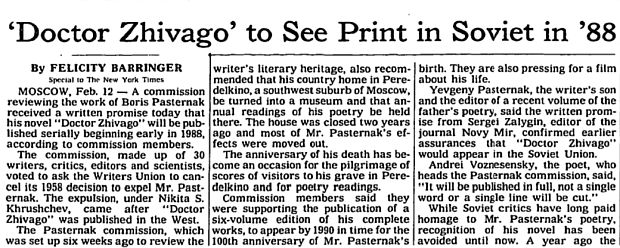

Part of a February 13, 1987 story in the New York Times on a “Pasternak commission” in the Soviet Union then working to reinstate Pasternak’s standing and works in his homeland, including the publication of “Doctor Zhivago” in Russia the following year, plus a proposal to establish a Pasternak museum at his former home at Peredelkino.

In 1987 the Union of Soviet Writers posthumously reinstated Boris Pasternak, a move that gave his works a legitimacy they had lacked in his homeland since his expulsion from the writers’ union in 1958. The reinstatement also made possible the first Soviet publication of Doctor Zhivago – initially serialized in Novyi Mir, the literary monthly. The first 102-page installment from the novel appeared in its January 1988 edition. Additionally, a six-volume edition of Pasternak’s complete works was also slated to appear by 1990 in time for the 100th anniversary of his birth year. Also arriving in 1990 were new biographies on Pasternak.

Evgeny Pasternak’s 1990 book on his father, “Boris Pasternak: The Tragic Years, 1930-60.” Click for copy.

Evgeny had begun work on his father’s literary estate in the 1960s, and since 1975, with an appointment as a Research Fellow at the Institute of World Literature in Moscow, he devoted himself full time to that work.

“…Drawing on previously unpublished correspondence and including a considerable number of unpublished poems and early drafts,” noted the book’s publisher, “Evgeny Pasternak’s memoir gives us a clear idea of how, and at what cost, Pasternak survived these tragic years.”

In one review, Pasternak scholar Christopher Barnes noted, “,,,Evgney Paster-nak’s meticulously documented account is remarkable for its sobriety and objective stance.”

Gordon McVay, in another review, added: “Evgeny Pasternak never conceals the awfulness of the era, and the signified heroism of his father’s quest to preserve personal, artistic, and spiritual integrity in a sea of mistrust, conformity and oppression.” The Pasternak poetry included in the book was translated by Ann Pasternak Slater and Craig Raine Pasternak.

Peter Levi’s 1991 book, “Boris Pasternak: A Biography,” among a number of books & commentaries appearing on Pasternak at centennial of his birth year. Click for copy.

In 1989, Christopher Barnes published Boris Pasternak: A Literary Biography, Volume I: 1890-1928 (Cambridge University Press, 507 pp).

In April 1990, Lazar Fleishman, a Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at Stanford University and long-time Pasternak scholar, published, Boris Pasternak: The Poet and His Politics (Harvard University Press, 359 pp).

And in early 1991, Peter Levi, a British poet, archaeologist, travel writer, biographer, reviewer and critic, and former professor of poetry at the University of Oxford, published, Boris Pasternak: A Biography (Hutchinson, 310 pp).

In early February 1990, Pasternak’s former home in Peredelkino, where he wrote some of his most famous works, was opened as a museum.

Also in 1990, came a 90-minute British-Soviet TV production titled “Pasternak,” by Russian-borne, New York writer and director, Andrei Nekrasov. Pasternak’s life is traced through archival films and dramatizations, using Soviet actors, combined with scenes from the 1965 “Doctor Zhivago” film. “Pasternak” aired on U.S. television in May 1990.

Soviet Archives

From the late 1990s through mid-2000s, there came new reports on Pasternak-related history from the Soviet archives and newly-released letters and memos from the Communist Party’s Central Committee.

William Taubman’s book, “Khrushchev, The Man and His Era.” Elsewhere, Khrushchev reportedly said in an audio diary he felt “sorry” that he didn’t support Pasternak. “I regret that I had a hand in banning his book and that I supported the hard-liners...” Click for Taubman book.

A Moscow newspaper had published extracts from a 1961 letter she supposedly wrote of her own volition to Nikita Khrushchev seeking her freedom, in which she recounted incidents of working with the Central Committee trying to delay publication of Doctor Zhivago in the West, writing statements for Pasternak in turning down the Nobel Prize, and dissuading him from leaving the Soviet Union.

Reportedly, it was quite common for prisoners in the gulag to write almost anything to gain their freedom, especially when tortured and/ or isolated while in prison.

And while there were those inclined to believe the reports of Ivinskaya’s alleged betrayal, others, such as Yvgeny Pasternak, son of Boris Pasternak and first wife, Evgenia Lurye, did not believe the allegations.

“It’s not true that she was disloyal,” Yvgeny said after the story broke. “If she wanted to betray him, she could have done it many times before, when Stalin was still alive, for instance. Many people wrote such letters…”

Other information that surfaced from Soviet-era documents in 2001 showed that even Pasternak’s unpublished manuscript for Zhivago in the mid-1950s had drawn fire from party officials. “Boris Pasternak’s novel is a malicious libel of the USSR,” wrote Soviet Foreign Minister Dmitry Shepilov in an August 1956 memo to members of the Central Committee. And one KGB memo on Pasternak;s writing noted, “a typical feature of his work is estrangement from Soviet life and a celebration of individualism.”

However, not all the revelations were negative. In late 2006, came reports that Nikita Khrushchev, who had secretly recorded his memoirs in an audio diary, had expressed remorse at the way he had treated Pasternak. “… I feel sorry that I didn’t support Pasternak,” he is alleged to have recorded in that diary. “I regret that I had a hand in banning his book and that I supported the hard-liners. We should have given the readers the opportunity to reach their own verdict. I am truly sorry for the way I behaved toward Pasternak. My only excuse is that I didn’t read the book.“

But then came the CIA revelations.

Cover used for early editions of “The Zhivago Affair: The Kremlin, The CIA, and the Battle Over a Forbidden Book,” by Peter Finn & Petra Couvée. Click for copy.

The CIA & Zhivago

In January 2007, Peter Finn of the Washington Post reported that a Russian historian – Ivan Tolstoy, grandson of an acclaimed Soviet-era novelist, Alexei Tolstoy – was about to publish a book with the title, “The Laundered Novel,” in which he would claim that in 1958 the CIA was a covert financier of a Russian-language edition of Doctor Zhivago, used, among other purposes, to help Pasternak secure the Nobel Prize that year (there would be no evidence of that, however). Tolstoy had previewed his book during a Moscow lecture, and it would be published in 2009.

Back in Washington, meanwhile, Peter Finn at the Washington Post began his own investigation into the alleged CIA connection to Doctor Zhivago, emerging some years later in 2014 with his own book, co-authored with Petra Couvée, a writer and translator who taught at Saint Petersburg State University in Russia. That book, published by Pantheon in July 2014 was titled, The Zhivago Affair: The Kremlin, The CIA, and The Battle Over a Forbidden Book.

As Finn and Couvée would later explain in reporting ahead of their book’s release, a secret package from British intelligence had arrived at CIA headquarters in January 1958 bearing two rolls of film. What the film bore were Russian-language pages of Doctor Zhivago, then banned by Soviet authorities. The Brits suggested the CIA might do some creative things with this novel behind the Iron Curtain. The CIA was soon “all in,” as they say – then no stranger to the use of literature in the propaganda wars. In fact, during the Cold War, as many as 10 million books and magazines – some contested and/or banned – were secretly distributed by the CIA behind the Iron Curtain as part of political warfare campaigns. But the Doctor Zhivago book would soon prove to be a special case.

“This book has great propaganda value,” an internal CIA memo explained, “not only for its intrinsic message and thought-provoking nature, but also for the circumstances of its publication: we have the opportunity to make Soviet citizens wonder what is wrong with their government, when a fine literary work by the man acknowledged to be the greatest living Russian writer is not even available in his own country in his own language for his own people to read.”

And with that, off went the CIA crew to do their nefarious deeds on behalf of the greater good – or rather, to simply make the powerful novel extolling life, liberty and personal freedoms available to Russian citizens to read in their own language, also absorbing its anti-Soviet sentiments.

Later paperback edition of “The Zhivago Affair: The Kremlin, The CIA, and The Battle Over a Forbidden Book” (368 pp), by Peter Finn and Petra Couvée, first published in 2014. Click for copy.

CIA officials believed there was “tremendous demand” for copies of the book among Russian students and intellectuals and authorized another venture. This time, an in-house printing of “miniature” pocket-size editions of Doctor Zhivago in Washington, D.C. was approved, also rendering the novel in thinner volume 1 and 2 versions, easier for reader smuggling into the homeland. These editions used a fictitious Paris printer on title pages.

“By July 1959,” reported Finn and Couvée, “at least 9,000 copies of a miniature edition of Doctor Zhivago had been printed in a one and two volume series.” As Finn and Couvée further explained:

…Two thousand copies of this edition were also set aside for dissemination to Soviet and Eastern European students at the 1959 World Festival of Youth and Students for Peace and Friendship, which was to be held in Vienna.

There was a significant effort to distribute books in Vienna — about 30,000 in 14 languages, including, 1984, Animal Farm, The God That Failed and Doctor Zhivago. Apart from a Russian edition, plans also called for Doctor Zhivago to be distributed in Polish, German, Czech, Hungarian and Chinese at the festival.

…When a Soviet convoy of buses arrived in sweltering Vienna, crowds of Russian emigres swarmed them and tossed copies of the CIA’s miniature edition through the open windows.

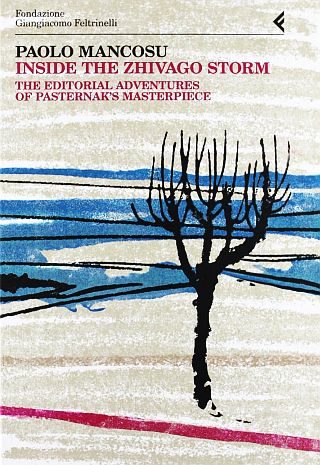

Paolo Mancosu’s October 2013 book, “Inside the Zhivago Storm. The Editorial Adventures of Pasternak's Masterpiece” (Feltrinelli, 416 pp). Click for copy.

In October 2013, Paolo Mancosu, a Professor of Philosophy at the University of California at Berkeley, then working with Italian publisher Feltrinelli, and accessing the publisher’s archive on the Doctor Zhivago novel, published, Inside the Zhivago Storm. The Editorial Adventures of Pasternak’s Masterpiece (an English and Italian edition, Feltrinelli, 416 pp.). This volume also delves into the hidden roles of the KGB and the CIA.

Mancosu would also publish two subsequent works on the Pasternak-Zhivago story.

In September 2016, Mancosu published, Zhivago’s Secret Journey: From Typescript to Book (Hoover Institution Press, 304 pp), which also uses declassified CIA documents in part of its story.

That volume was followed by another in March 2019 — Moscow Has Ears Every-where: New Investigations on Pasternak and Ivinskaya (Hoover Institution Press, 396 pp).

During the mid and late 2010s, there had also been other books on Pasternak, and at least one hour-long documentary BBC film titled, “The Real Doctor Zhivago,” focused on Pasternak’s career. That film aired on BBC in October 2017, was narrated by Stephen Smith, and also followed the making of Pasternak’s novel, including its use by the CIA during the Cold War.

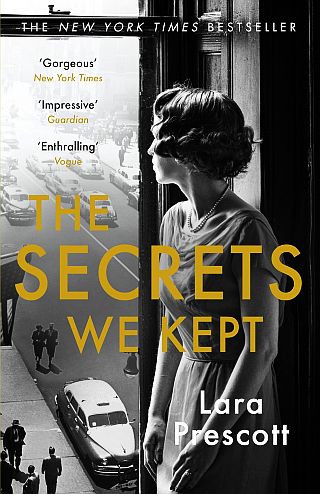

But in 2019, a new literary twist would arrive in the Pasternak-Zhivago publishing world in the form of a fictional treatment – and more on point, as a historical spy novel.

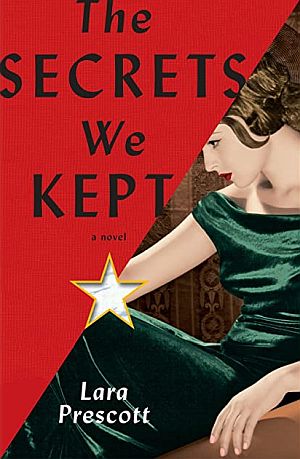

Original cover art for first edition of Lara Prescott’s “The Secrets We Kept,” 2019 Knopf hardback. Click for copy.

The Prescott Novel

Lara Prescott – who ironically was named Lara for her mother’s fondness for the Lara character in the 1965 Zhivago film – had been a young writer engaged in Washington, DC- based progressive politics, but gave that up to pursue and obtain a Masters in Fine Arts degree at the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas.

In 2014, her father sent her the Peter Finn / Petra Couvée Washington Post story noted above on the CIA’s use of the Doctor Zhivago novel in the propaganda wars. And soon, Prescott was consumed by the story, delving into the original CIA documents, and musing about the redacted portions. That’s when she began thinking about “filling in” those redactions with her own creations.

And before long, coupled with an interest in the history and female characters of the CIA’s secretarial pool following WWII, she would — after some fits and starts, revisions, and “sticking-to-it writing” – soon produce a spy novel revolving around the CIA’s Doctor Zhivago doings in Russia with its own unique internal love story.

By 2018, Prescott had an agent, a manuscript, and a plan to maybe land a $100,000 book deal, an amount, she then figured, that might provide enough income for about three years of full-time writing. But soon, more than a few publishers began calling, and the book went to auction. A bidding war ensued, with 20 publishers interested. In the end, Prescott settled on Alfred Knopf to publish her novel in a $2 million deal.

Prescott’s story puts women at the center of her novel, including Olga, the real-life mistress of Boris Pasternak, whose devotion to the married author sent her twice to the gulag.But the “stars” of the spycraft portion of Prescott’s novel are Irina Drozdova, a Russian immigrant recruited from the CIA typing pool, and Sally Forrester, a veteran who takes the novice under her wing and trains her. Their mission is to first smuggle Pasternak’s Zhivago out of the USSR in order to publish it, and then disseminate the banned book back into the Soviet Union for public consumption. Along the way there is intrigue, risk, and love.

Prescott’s book became a best seller in 2019, receiving rave reviews.

The Los Angeles Review of Books compared it to classic Russian literature, noting: “Lara Prescott’s debut follows in the footsteps of classic Russian novels by being an epic love story that is both brilliant and bleak, one that is wound into the fabric of tragic, true history…”

The New York Times called it a “gorgeous and romantic feast of a novel” and Vogue praised it “a stunning spycraft debut.”

Michael Thomas Barry in his review of the book for the New York Journal of Books noted: “The Secrets We Kept is a remarkable debut novel and Prescott’s fictionalized interpretation of the Soviet Union’s suppression and the CIA’s covert distribution of Doctor Zhivago is meticulously researched…”

In 2019, Prescott had a lawsuit filed against her by Anna Pasternak, niece of Boris Pasternak and author of the non-fiction book, Lara: The Untold Love Story and the Inspiration for Doctor Zhivago. She claimed The Secrets We Kept had infringed on her book and that Prescott had copied material from her book. But in 2022, Anna Pasternak lost that case, with the high court in London finding no grounds for the suit and that nothing had been copied from The Secrets We Kept.

Prescott’s book, meanwhile, has been printed in 30 countries and also had its film rights sold early on. A feature film was reported to be in production by the Ink Factory and producer Marc Platt, whose earlier films included La La Land, Bridge of Spies, and Legally Blonde.

October 1958. Russian writer and poet, Boris Pasternak, near his home in the countryside outside Moscow. Harold K. Milks / Associated Press

The intertwined Boris Pasternak/ Doctor Zhivago stories have had long shelf lives, now stretching well over a century from Pasternak’s 1890 birth year. These are classic and epic stories, burnished not only by government repression, Nobel Prize distinction, and political warfare, but also continued publishing, scholarly inquiry, and cultural embedding in film, music, and television.

Certainly contributing to the lasting effects of the Pasternak/Zhivago stories is the humanism, integrity, and true grit of the characters involved — fictional and otherwise — as well as the love stories. Russian writers since Tolstoy, it appears, have been especially good at capturing these elements, and new writers will likely emerge in that tradition as Russia continues to struggle with its identity and politics in present times, bringing new works of humanism that illuminate and offer hope for a better world.

See also at this website the companion “Doctor Zhivago” story on the classic 1965 Hollywood film starring Omar Sharif and Julie Christie. That story includes numerous screenshots from the film with running narrative, soundtrack samples, reviews, critic quotes, director and screenwriter comment, global box-office returns, awards received, and more. For additional stories on Publishing and/or Politics, see those respective category links. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing, and continued publication of this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle.

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 9 November 2023

Last Update: 9 November 2023

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/PopHistoryDig

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “The Pasternak Saga …and Zhivago Chronicles,”

PopHistoryDig.com, November 9, 2023.

____________________________________

Film Choices at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“Boris Pasternak – Biographical,” NobelPrize .org.

“Boris Pasternak,” Wikipedia.org.

“Doctor Zhivago (novel),” Wikipedia.org.

“Boris Pasternak, Chronology,” The Pasternak Trust, A Family Collection/Pasternak-Trust .org.

Arnaldo Cortesi, “New Soviet Novel Appears in West; Italy Publishing Pasternak Work That Moscow Tried to Hold Up for Revision,” New York Times, November 21, 1957, p. 15.

Max Frankel, “Russian Regrets Storm Over Book; Pasternak, Interview, Says Novel Barred by Moscow Reflects Trend of Times,” New York Times, December 17, 1957, p. 22.

Marc Slonim, “But Man’s Free Spirit Still Abides; Out of Russia Comes a New Novel That Defies the Totalitarian’s Way” (Review of Boris Pasternak’s “Doctor Zhivago,” Pantheon Books), New York Times Book Review, September 7, 1958, pp. 151, 191.

Werner Wiskari, “Nobel Prize Goes to Pasternak; Russian’s ‘Zhivago’ Still Unpublished in Soviet Union,” New York Times, October 24, 1958, pp. 1, 6.

Max Frankel, “Soviet Calls Nobel Award To Pasternak a Hostile Act; Moscow Assails Pasternak Prize,” New York Times, October 25, 1958, p. 1.

Max Frankel, “Dispatch Is Held Up; Report of Pasternak Interview Fails to Clear Moscow,” New York Times, October 25, 1958, pp. 1, 19.

Associated Press, “Pasternak Abused in Pravda Editorial,” New York Times, October 27, 1958, p. 2.

“A Brave, Defiant Russian Writer,” Life ( photographer, Jerry Cook), October 27, 1958, pp. 139-142.

Reuters, “Writers in Soviet Expel Pasternak; Nobel Prize Winner Scored as Pawn in Cold War,” New York Times, October 28, 1958, pp. 1, 3.

Werner Wiskari, “Author Tells Swedes He Cannot Accept Nobel Literature Award; Pasternak Says He Rejects Prize,” New York Times, October 30, 1958, pp. 1, 3.

Max Frankel, “Young Communist Head Insists Writer Go to ‘Capitalist Paradise’; Pasternak Urged to Leave Soviet,” New York Times, October 30, 1958, pp, 1, 2.

Max Frankel, “Clamor Grows in Moscow for Exiling of Pasternak; Russians Demand a Pasternak Ban,” New York Times, November 1, 1958, pp. 1, 6.

Max Frankel, “Pasternak, Fearing Exile, Pleads With Khrushchev; Note Says Banishment Would Mean Death – He Admits Errors,” New York Times, Sunday, November 2, 1958, pp. 1, 2.

United Press International, “Pasternak Is Ailing, His Wife Declares,” New York Times, November 3, 1958, p. 1, 5.

Reuters, “Pasternak Issues a Public Apology; Writes Pravda He Erred in Hailing ‘Political’ Prize — Regrets Effect of Book,” New York Times, November 6, 1958, p. 4.

James H. Billington, “Nikita Khrushchev and ‘Doctor Zhivago’.The Pasternak Case Underlines Moscow’s Dilemma: To Give Intellectuals Freedom to Produce What the Regime Needs — and Yet to Keep Them on a Strong Leash,” New York Times Magazine, November 9, 1958, pp. 290, 354-358

Associated Press, “Pasternak Cited at Nobel Session; Prize to Soviet Writer Still Valid, Official Declares at Presentation Ceremony 7 Winners Get Awards 3 U. S. Scientists, Briton, 3 Russians Honored Before 2,000 in Stockholm,” New York Times, December 11, 1958, p. 15.

“The Passion of Yuri Zhivago,” Time (cover story), Monday, December 15, 1958.

Harry Braverman, “The Case of Dr. Zhivago,” The American Socialist, December 1958, pp. 6-8.

Jules Chemetzky, “Boris Pasterak’s Epic Novel” (review), The American Socialist, December 1958, pp. 9–11..

“Pasternak, in New Poem, Sees ‘No Way Out’. But He Is Angered by a London Paper’s Disclosure of Verse,” New York Times, February 14, 1959, p. 1.

“Pasternak Stands on ‘Zhivago’ Views,” New York Times, February 19, 1959, p. 4.

“Legend and Symbol in Dr. Zhivago,” The Nation, April 25, 1959.

“The Book That Shook the Kremlin. Revealed, the Dramatic Story of a Communist Rebel’s Fight to Rescue Doctor Zhivago from Oblivion,” Coronet (magazine), 1959.

Associated Press, “Pasternak Is Dead, Wrote ‘Dr. Zhivago’ …Soviet Writer, 70,” New York Times, May 31, 1960, pp. 1, 29.

“Foreign News: Death of a Man,” Time, June 13, 1960.

Rosette C. Lamont, “‘As a Gift…’, Zhivago, the Poet,” PMLA (Journal of the Modern Language Association of America), Vol. 75, No. 5, Cambridge University Press, December 1960, pp. 621-633..

Jahn Robbins, “Boris Pasternak’s Last Message To The World,,” This Week Magazine (nationally-syndicated Sunday supplement), August 7, 1960, pp. 4-5, 12.

Harrison E. Salisbury, “Pasternak Letter, Citing Illness, Rebuts Charge Against Friend; 1959 Note to German Indicates Author, Sensing Early Death, Originated Idea of Sending Funds to Mme. Ivinskaya,” New York Times, February 4, 1961, p. 5.

Edwin McDowell, Publishing, “A Full-Scale Biography of Pasternak,” New York Times, November 6, 1981.

“In Soviet Literary Life The Hazards Endure,” New York Times Book Review, June 21, 1964, pp. 4-5, 22.

“Pasternak Aide Freed in Soviet,” New York Times, November 2, 1964.

David K. Shipler, “Moscow Protests Viewing of ‘Zhivago’; Film and Another Shown Privately by American Diplomats Are Described as Slanderous,” New York Times, April 16, 1977.

“The Unpublished Letters of Boris Pasternak”(edited and translated by Elliott Mossman), New York Times Magazine, January 1, 1978.

Irving Howe, “Lara and Zhivago” (Review, Olga Ivinskaya, A Captive of Time: My Years With Pasternak), New York Times Book Review, February 5, 1978, p. 1.

Helen Muchnic, “Two Lives Caught in History,” (Review: The Correspondence of Boris Pasternak and Olga Freidenberg 1910-1954), New York Times Book Review, June 27, 1982.

E. Wasiolek, Review, Boris Pasternak: His Life and Art, by Guy de Mallac, Modern Philology, Vol. 80, Nor 4, University of Chicago Press, May 1983.

Felicity Barringer, “‘Doctor Zhivago’ to See Print in Soviet in `88,” New York Times, February 13, 1987.

Associated Press, “’Zhivago’ [the book] Appears in Russia,” New York Times, January 14, 1988.

David Remnick, “The Pasternak Attack,” Washington Post, March 9, 1988.

John J. O’Connor, Review/Television, “Merging Zhivago With His Creator,” New York Times, May 31, 1990, p. C-20 (re: “Pasternak,” TV film by Director, Andrey Nekrasov).

Neil Cornwell, “Centennial Publications on Pasternak: A Review Article,” The Modern Language Review, Vol. 86, No. 3, July 1991, pp. 645-650.

“Olga Ivinskaya, 83, Pasternak Muse for ‘Zhivago’,” New York Times, September 13, 1995, p, B-8.

Jeanne Vronskaya, “Obituary: Olga Ivinskaya,” Independent.co.uk, September 13, 1995.

Alessandra Stanley, “Model for Dr. Zhivago’s Lara Betrayed Pasternak to K.G.B..” New York Times, November 27, 1997, p. 1.

Daniel Williams, “Pasternak’s ‘Lara’ Lives on in Court Case,” Washington Post, February 1, 1998.

“Olga Ivinskaya,” Wikipedia.org.

Denis Kozlov, “‘I Have Not Read, But I Will Say,’ Soviet Literary Audiences and Changing Ideas of Social Membership, 1958-66,” Kritika, Vol. 7, Issue 3, Summer 2006.

Rob Rand, “Pasternak’s Funeral: A Poetic Protest,” NPR.org/Weekend Edition, Sunday, November 5, 2006.

Peter Finn, “The Plot Thickens A New Book Promises an Intriguing ‘Twist to the Epic Tale of ‘Doctor Zhivago’,” Washington Post, January 26, 2007.

Peter Finn and Petra Couvée, “During Cold War, CIA Used ‘Doctor Zhivago’ as a Tool to Undermine Soviet Union,” WashingtonPost .com, April 5, 2014.

Jeffrey Brown, “Why ‘Doctor Zhivago’ Was Dangerous,” PBS.org/NewsHour, July 8, 2014.

Michael Kimmage. “How the CIA Stole ‘Dr. Zhivago’. The Novel Stood in Subtle Opposition to Much That Soviet Life Tried to Destroy,” The New Republic, June 21, 2014.

Beth Ann Reimel, “Pasternak, Boris: Doctor Zhivago,” 20th Century American Bestsellers, University of Virginia. (John Unsworth, Department of English), 2016.

“New BBC Documentary Explores the Fascinating Story Behind ‘Doctor Zhivago’,” BritishPeriodDramas.com, October 12, 2017.

Elizabeth Kiem, “The Other Zhivago Affair: Anna Pasternak Rights an Ancestral Wrong, But Can’t Help Playing Matchmaker . . .” (re: book, Lara), Medium.com, January 24, 2017.

Quintus Curtius, “A Phone Call With Stalin,” QCurtius.com, November 18, 2017.

Sam Tanenhaus “Three Blockbuster Novels From the 1950s, and Their Remarkable Afterlife,” NYTimes.com, September 12, 2018.

Tina Jordan, “The ‘Doctor Zhivago’ Nobel Dust-Up,” NYTimes.com, October 24, 2018.

Leah Greenblatt, “The Secrets We Kept Is a Crackling, Female-Centered Spy Thriller Rooted in Real Life,” EW.com /Entertain-ment Weekly, August 28, 2019.

Caryn James, “Reimagining the True-Life Intrigue Behind ‘Doctor Zhivago,’ In ‘The Secrets We Kept,’ First-time Novelist Lara Prescott Uses Fiction to Fill in the Blanks in Real-Life Events—Inspired by a Trove of CIA Documents,” Wall Street Journal, August 29, 2019.

Janet Maslin, “A Debut Novel Reimagines the C.I.A.’s Efforts to Promote ‘Doctor Zhivago’,” NYTimes.com, September 2, 2019.

Valeria Paikova, “How Major Russian Poets Tried to Communicate with Stalin,” Russia Beyond/RBTH.com, October 15, 2021.

Haroon Siddique, “Descendant of Doctor Zhivago Author Loses Copyright Court Case; Anna Pasternak Alleged Lara Prescott Copied Elements of Her Book about Her Great Uncle Boris’s Lover,” TheGuardian.com, October 25, 2022.

Rebecca Abrams, “A Dictator Calls — What Did Stalin Really Say on the Phone? Ismail Kadare Digs Deep into a Fabled Telephone Conversation That May Have Sealed the Fate of a Dissident Russian Poet,” (review of A Dictator Calls, by Ismail Kadare), Financial

Times, September 8, 2023.

__________________________________________________

Soviet History at Amazon.com…