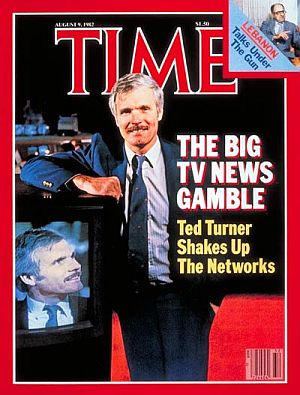

Ted Turner on cover of 9 August 1986 Time magazine, which said of his up-and-coming 24-hour news network: ‘...By any measure, CNN is in the big leagues of news.’

Yet by the early 1980s, Ted Turner was a bona fide success story and a man on the rise. In the 1980s-thru-1990s transformation of Big Media, Ted Turner became a central player; a maverick outsider taking on the Big Boys and holding his own, breaking new ground in the process.

Turner began his ascent from a family billboard business in Atlanta, Georgia, became a small cable TV operator, and then used satellite capability to make a local TV station a “superstation.” He rose quickly to become the near-equal of the major TV networks in less than a decade, coming from out of nowhere.

Turner’s key invention would become CNN — the Cable News Network — which not only touched off a revolution in the news business, but also helped show the enormous potential of cable television generally. Earlier than most, Ted Turner saw clearly all the pieces on the chessboard, and had a strategy in mind to make major change. Perhaps more than any other single individual, Turner was responsible for pushing cable TV into the mainstream — both in America and globally. Turner’s ventures also spurred a gold rush among his competitors, media moguls, and assorted entrepreneurs seeking to get in on the action. But earlier than most, Ted Turner saw clearly all the pieces on the chessboard, and had a strategy in mind to make major change. He envisioned how technology, public policy, and consumer interest might be aligned to capture a new kind of media synergy. But making that a reality was no cake walk for Turner. He faced naysayers and all manner of obstacles. But with tenacity and hard work — which Turner gave in full measure despite a not-always-deserved playboy and care-free image — he made his mark, changing the way much of the world would use television, especially television news. Part of his story begins in the early 1960s.

Billboards to Television

In 1963, at the age of 24, after his father committed suicide, Ted Turner found himself suddenly in charge of the family billboard business. Turner Advertising, a regional business based in Atlanta, Georgia, was built by his father. Young Ted, from about the age of 12, had worked in the family business, learning the ropes from the bottom up. “I started as a bill poster,” he said in one interview, “constructing billboards and painting them and maintaining the billboards. I did that for about five years. Then, when I got to be about 17 years old, I put on a coat and tie and went out with our sales manager to learn sales.” He learned the business well. Becoming head of the company in 1963, he wanted to do an especially good job in his father’s memory. Saddled with debt when he first took over, he dug in and worked hard. By the end of the decade, the business was profitable and he had made it the largest outdoor advertising business in the southeast U.S. But it was about then that Ted Turner began to see something more. His billboard advertising clients were spending more of their money on radio and TV ads, not outdoor advertising. So Turner began looking in that direction as well.

Ted Turner’s advisors worried when he used $2.5 million to buy a money-losing TV station in Atlanta, Georgia.

To the dismay of his financial advisors, Turner traded $2.5 million worth of his own company’s stock for title to the Atlanta UHF station. He also later bought another UHF station in Charlotte, North Carolina. Ted Turner was on his way in the television business. Still, UHF had it difficulties, was awkward for consumers to use, and wasn’t always the first choice of TV viewers. Turner by then had changed the name of his firm to Turner Communications Group, recasting his Atlanta TV station’s call letters to WTCG — also rumored to mean “watch this channel grow.” However, at first, Turner’s new UHF stations lost money. Undaunted, he kept buying up programming and broadcast rights to old movies and old TV re-runs to use on his stations.

|

WTCG: Music Video Turner’s first TV station appears to have had an eclectic mix of programming in the early, pre-satellite 1970s. The station had some rough days and rough edges. It was the only station in Atlanta that still broadcast in black-and-white. Turner had trouble paying the bills there too, resorting to an on-air telethon to raise money, much like PBS does today. A competitor UHF station in Atlanta, WATL, was also a problem for a time. But Turner’s WTCG prevailed, helped in part by stealing a popular WATL music video show called The Now Explosion, a pre-MTV-like show that ran music videos, some pretty bad, all weekend long. Turner’s WTCG also may have been ahead of its time with its John Daly-like comedic TV, if only by accident, as the FCC required a news broadcast. So WTCG produced some humorous, satirical early-a.m. newscasts. Its 17 Update Early in the Morning, for example, featured straight-faced reporters along with comedic sidelines, including “The Unknown Newsman,” a co-anchor wearing a brown paper bag over his head. But WTCG’s bread-and-butter programming soon included lots of Atlanta Braves baseball and Atlanta Hawks basketball, reruns of Star Trek, and Georgia Wrestling. And there were bigger and better things on the way. |

Turner was also paying attention to what was going on in the new cable TV business. Then in its infancy, the pieces of that industry were coming together in the early 1970s.

In 1972, the FCC ruled that cable TV operators could import distant signals. In New York, Time, Inc., the giant publishing company, had acquired a small Manhattan-based cable TV company which it later renamed Home Box Office. HBO thus became one of the first cable systems to transmit movies to subscribers over its cable network.

In 1975, RCA’s Satcom II satellite was launched and put into operation. Time-HBO was also the first to see the potential of linking satellite programming to its cable systems. But Ted Turner was also paying attention to these developments, as he later explained:

“I read the broadcasting magazines, and they wrote several stories about Home Box Office, and they planned to go on the satellite with their pay movie service and try and get cable systems to sign up…” A week after he read that, Turner headed up to New York to meet with RCA. Turner soon used the FCC distant signal rule and the RCA satellite capacity for his Atlanta station. “That’s how we were able to beam our Atlanta station to homes throughout the South,” he would later explain.

Still, even then, the established broadcast networks tried to squash Turner before he even started; they went to Congress stop him. But Turner fought back, lobbying Congress about the evils of network monopoly and he beat them. He also made what would prove to be an important programming purchase in January 1976: buying the Atlanta Braves professional baseball team for a price then estimated in $10-to-$12-million range. He would also buy the Atlanta Hawks basketball team the following year.

Meanwhile, Turner’s new satellite-enabled Atlanta TV station had a new patina; it was now more than just a local UHF station. In fact, Ted Turner had invented something quite new; something that was would be called a “superstation.”

“Superstation”

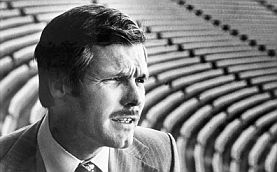

Ted Turner in Atlanta Stadium, February 1976, shortly after buying the Atlanta Braves baseball team.

At first, Turner’s station ran old movies and old situation comedies like The Andy Griffith Show and Green Acres. But then in 1976 Turner acquired the Atlanta Braves professional baseball team and he soon began sending out a full-season roster of Braves games over his new superstation. Baseball broadcasting then was still pretty restricted to locally-telecast games mostly in a few big markets that had professional teams. As Turner recalled in a later interview:

“…Most of America only got a Saturday afternoon game on NBC, and all of a sudden, here was a complete slate of 150 baseball games, most of them in prime time.“Nielsen wouldn’t give us the ratings for several years. I had to threaten to sue them to rate us.” So people in Nebraska and North Dakota and South Dakota, Hawaii and Alaska could have a team to cheer for that they never had before. No, it was good programming. We carried wrestling, and people liked that. Wrestling, baseball, basketball and movies and some other sporting events that we could get our hands on. We had a very, very viable, popular network there.

And it eventually started making money. It took a long time. I was so poor for a long time. Nielsen wouldn’t give us the ratings for several years. I had to threaten to sue them to rate us….”

An “All News” Network

In late September 1975, Time’s HBO, linking satellite capability to cable systems, broadcast the famous “Thrilla in Manila” heavyweight championship fight between Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali to its subscribers. It showcased the new global potential of television. In Atlanta, Ted Turner was also thinking about the power of cable’s new reach via satellite, and specifically about news. Recalls Turner:

“…In the 1970s, I became convinced that a 24-hour all-news network could make money, and perhaps even change the world. But when I invited two large media corporations to invest in the launch of CNN, they turned me down. I couldn’t believe it. Together we could have launched the network for a fraction of what it would have taken me alone; they had all the infrastructure, contacts, experience, knowledge. When no one would go in with me, I risked my personal wealth to start CNN.”

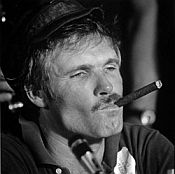

Ted Turner at launch of CNN, June 1980.

Turner himself would later say: “You know, it was a real good plan. It was a plan to conquer the world, but with ideas, not with weapons.” Adds New York writer Ken Auletta: “Turner wanted to shrink the world. He wanted Americans to understand the world, and not be isolationist, not be comfortable in our little cocoons.”

Turner was joined by some like-minded souls in his venture; people who wanted to be part of his fight. Among these was Bernard Shaw, a former ABC newsman who would become one of CNN’s first anchormen: “I wanted to twit the traditional networks. Those people at ABC, CBS, and NBC who said, this will not work, they are inept…. I wanted to join Ted, along with the other men and women at CNN, to prove those bastards wrong.”

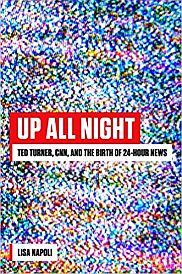

In June 1980, Turner’s CNN, the Cable News Network, was formally launched, becoming the first 24-hour, all-news network. But initially, it wasn’t at all clear the network would fly. “Soon after our launch in 1980, our expenses were twice what we had expected and revenues half what we had projected,” Turner later explained. “Our losses were so high that our loans were called in. I refinanced at 18 percent interest, up from 9, and stayed just a step ahead of the bankers.”

June 1980. Early Newsweek coverage of CNN's new venture.

CNN jumped in to cover all kinds of news events in its first year, from the 1980 Democratic and Republican presidential conventions just a few weeks after its launch, to the shooting death of the Beatles’ John Lennon that December. Not all of the coverage went smoothly, and some was disastrous, while CNN reporters and producers faced ridicule from news colleagues at other networks, some calling it the “Chicken Noodle Network.” Yet the value of CNN quickly became apparent, especially in breaking news. CNN was the first in March 1981 to report that President Reagan had in fact been hit during John Hinckley’s assassination attempt. It stayed on the air while ABC and CBS switched back to regular programming after telling their viewers, as was first believed, that the President was unhurt. CNN would go on to gain other firsts in breaking news, and their later gavel-to-gavel coverage of subsequent Republican and Democratic political conventions would also win them praise.

WTBS Makes Money

Changing look at the logo for Ted Turner’s WTBS Atlanta ‘superstation’ over the years, 1979-2004.

…Turner has shown that there is a substantial and eager audience for news all the time, not just in the confined hours at the beginning and end of the workday. In two years his 24-hour-a-day service has grown to …13.9 million households…. Editorially, it scoops the Big Three networks on a fair share of stories. By any measure, CNN is in the big leagues of news.

Each of the Big Three broadcast networks by this time — ABC, CBS and NBC — had started some kind of cable news unit, either late night or with other partners, acknowledging that Turner had shown there was an audience for round-the-clock news.“I was cable before cable was cool.”

– Ted Turner, May 1982. But these ventures were playing catch-up. Turner had the loyalty of many cable-system clients around the country, and even a healthy number of local broadcast stations who were affiliates of the Big Three. In May 1982, at the National Cable Television Association convention in Las Vegas, Turner held a big reception for the cable-system owners where he was warmly received. At this gathering, Turner also ran a bit of campaign to toot his own horn. A giant 3-D billboard of himself playing the guitar carried the tag line: “I was cable before cable was cool,” a line paraphrased from a country music song, also emblazoned on placards and buttons at the Las Vegas reception. But Ted Turner had more big plans to come.

August 1983: The New York Times reports on Turner’s rise in a Sunday, business section feature.

Turner and his new CNN were increasingly viewed as successful. By August 1983, the New York Times ran a front-page business-section story in a Sunday edition entitled, “Television’s ‘Bad Boy’ Makes Good,” reporting on CNN’s first profits. Ted Turner, however, was a man not easily defined; and in many ways, was a study in contradictions.

Ted Growing Up

Robert Edward “Ted” Turner III was born November 1938 in Cincinnati, Ohio. His family moved to Savannah, Georgia when he was nine, and young Ted was soon sent to the Georgia Military Academy. As a schoolboy, he did take well to football, basketball or baseball, though he tried them all. At home he was close to his father, a tough taskmaster who taught Ted business principles through living, even charging him rent during summer vacations. At graduation from his second military academy, the McCallie School in Chattanooga, Tenn., his father helped young Ted buy — partly with all of Ted’s hard-earned savings — a Lightning-class sailboat, a passion he had already picked up. Ted had dreams of the U.S. Naval Academy, but his father wanted an Ivy League education for his son. Turner had been scarred in his teens by the loss of his younger sister, Mary Jane, taken in a painful fight with a Lupus disease that causes the body to make antibodies against its own tissues. Unable to get into Harvard, Ted went to Brown and chose to study the Greek classics which outraged his father, “a practical man,” repulsed by Ted’s choice. A switch to an economics major soon followed. But Ted left Brown, suspended in 1960 for having a female in his room, a second infraction involving women. He then dropped out, went to Florida for a time, but soon returned to Georgia to join his father in the billboard business.

In his teens, Turner had been scarred by the loss of his younger sister, Mary Jane, stricken with a lupus disease that causes the body to make antibodies against its own tissues. Ted was about 15 at the time and his sister, three years younger. The disease tormented her, ravaging her nervous system to the point where, reportedly, carpenters were brought in to pad her room. She screamed, “God, let me die, let me die!” Turner later told Time: “She was sweet as a little button, she worshiped the ground I walked on, and I loved her. A horrible illness.” Then came his father’s death.

Ed Turner had become a millionaire by the time young Ted, then in his 20s, came home to work in the family billboard trade. But his father, unhappy with the business, signed an agreement to sell his company’s newly acquired Atlanta division. Then, at the age of 53, Ed Turner retreated to his South Carolina plantation in March 1963 and shot himself. Young Ted, then 24, immersed himself in the business, fighting ferociously to undo the deal his father had made to sell his company’s assets. Ted played hardball with the would-be owners. He threatened to “build billboards in front of theirs” among other tactics to get what he wanted. In a short time the business was his, and it became a huge success, which he later spun off as he dove into cable television.

Captain Courageous

During the 1970s, Turner also used his energies to pursue other interests, world-class sailing among them. He sailed in hundreds of races all over the globe and won the Americas Cup in 1977.Turner had grown up with sail boats, becoming known for taking risks on the water, dubbed “the capsize kid.” And he didn’t win, especially at first.

“In the first eight years that I raced sailboats, I never won,” Turner later explained. “I was sailing at Savannah Yacht Club in Savannah, Georgia, and I never won a club championship. I was second almost all the time, but I never won once in eight years. And then in my ninth year of racing, I went to college and started racing there, and all the work that I had done — because those first eight years, I wasn’t really losing. I was learning how to win…”

Turner entered the America’s Cup race in 1974 but lost. In 1977, he entered again with his yacht, Courageous. This yacht was older and less technically advanced than others in the race, but Turner defeated his competitors, earning the right to defend the cup against the world’s challengers. The final event was held in rough seas, but Turner prevailed.

1977 America's Cup victor.

Ted Turner in 1981 Cutty Sark ad.

Tenacious too, appeared to be doomed, swamped by high seas with 40-foot waves. But Turner and crew ran full out through the gale. Tenacious came in first of the 92 boats that completed the course. The 1979 Fastnet remains one of the deadliest ocean races in history, and Turner’s victory there has become legend.

The Association of Sailing Journalists named Turner Yachtsman of the Year three times, consecutively, a unique honor. And in 1981, whiskey maker Cutty-Sark featured Turner in sailing mode in one of its magazine ads (shown at right). “Here’s to Gut Feeling And Those Who Still Follow Them,” said the ad’s headline, also offering a short bio of Turner’s risk-taking accomplishments then to date. In 1979, Tuner published a highly-regarded book on sailing with Simon & Schuster, along with Gary Jobson, his tactician, titled, The Racing Edge: Sailing Techniques, Tactics and Philosophy of the America’s Cup Skipper and His Tactician (click for copy).

All Business

But it was Turner’s businesses that consumed most of his time, even to the neglect of his second marriage and two children from a previous marriage. As a young owner of the family billboard business, and as he began building his cable TV empire, Turner became a workaholic. In a 2007 interview he did with the Academy of American Achievement in Washington, Turner recounted a bit of his work habit:

“…[F]or 20 years, I lived at my office… I lived on a couch in my office for ten years, and then luckily, I got wealthy enough to build a little penthouse on the roof — 700 square feet — and I moved up there. It was a lot nicer. I just walked up the stairs one floor. …For 20 years, I lived at my office…

– Ted Turner on his work habit. My office was on the top floor, and I just walked up to go to bed, and that way, I had another hour to work every day, because when I walked downstairs, I was instantly in my office without having to fight traffic. So I was able to work an hour. I went to the games at night, and I’d get home at 11:00. I’d come back in the office, and I was right there: 7:00 when I woke up, to be at work at 8:00. I worked 18 hours a day, seven days a week. I liked it. I mean almost. Sometimes I’d go home to see my wife and family. I still live in my office. I live up above in a penthouse over my office building in Atlanta. The restaurant is down on the ground floor. So if I’m hungry, I just go down to the restaurant and eat and get a meal and then go back up, and I’m right there.”

1980s Expansion

Key assets for Turner in the 1980s were the MGM film & cartoon libraries he acquired, which helped provide programming for TNT & Cartoon networks.

However, in 1986, Turner scored big with the $1.5 billion purchase of the legendary but struggling Hollywood film studio MGM (plus United Aritists which had merged with MGM). He made that deal with investor Kirk Kerkorian.

Turner’s bankers, however, refused to back him concerned about an already heavy debt load at his companies. So he then sold much of the deal back to Kerkorian, with some important exceptions. Turner held onto MGM’s film library, the entire RKO library, and some United Artists television programs — entertainment assets that would help in Turner’s next ventures.

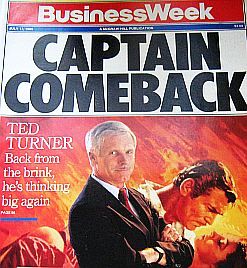

After his MGM deal, Business Week's cover of July 17, 1989 billed Turner as “Captain Comeback - Back From the Brink, He's Thinking Big Again”.

By 1987, more than 50 percent of U.S. households were wired for cable TV. In 1988, Turner founded TNT, the Turner Network Television channel. He introduced the channel with a special broadcast of Gone With the Wind. TNT, at least initially, was a vehicle for older movies and television shows, but slowly began to add original programming and newer reruns. TNT also used sports broadcasts and pro wrestling to attract a broader audience, and would later add NASCAR and NBA programming.

By the end of the 1980s, Ted Turner was the nation’s largest supplier of programming to cable systems, with sales climbing beyond $1 billion. CNN by then was reaching 53.8 million homes in the U.S. and another six million abroad. Turner himself was listed by Forbes magazine at No. 19 on its 1989 list of the “400 Richest Americans” with estimated wealth of $1.76 billion.

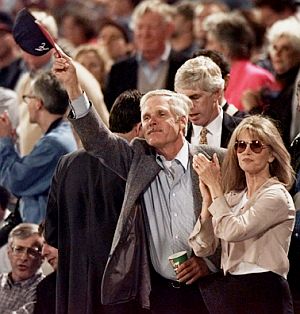

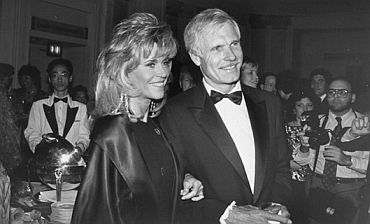

Ted Turner & Jane Fonda at baseball playoffs: Atlanta Braves vs. St. Louis Cardinals, National League Championship Series, Game 6, October 16, 1996. (Click for Jane Fonda story).

Although Turner still held 55 percent of Turner Broadcasting’s voting stock, the presence of TCI and Time-Warner on his board would have a tempering effect on Turner’s actions.

Still, through the early 1990s — in addition to marrying actress Jane Fonda in 1991 — Turner continued his business expansion, adding new cable channels.

In 1992, Turner’s MGM library, which included the cartoon libraries of Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies — plus the acquisition of another cartoon maker, Hanna-Barbera Productions — became the basis of the Cartoon Network.

In 1993, TBS merged with Castle Rock and New Line movie studios. Castle Rock had produced films such as: In the Line of Fire, A Few Good Men, City Slickers and When Harry Met Sally, as well as the popular Seinfeld television series. In 1994, the Turner Classic Movie (TCM) channel came next, primarily to broadcast the older Warner Brothers, RKO, and MGM libraries.

Cable News Network logo.

CNN, Big Time

CNN meanwhile was growing by leaps and bounds. CNN covered worldwide news as it unfolded, and by the late 1980s was a leader in covering events like Poland’s Solidarity movement, the Space Challenger disaster of 1986, China’s Tiananmen Square uprising in June 1989, the fall of the Berlin Wall in December 1989. But one of CNN’s biggest coups was its live, at-the-battlefront coverage of the first Gulf War in 1991. CNN was the only news outlet with the ability to communicate from inside Iraq during the initial hours of the American bombing campaign, with live reports from CNN’s Bernard Shaw, John Holliman, and Peter Arnett. Ted Turner later recounted his reaction to the coverage:

“… It was one of the most exciting moments of my life. I knew what was coming. We knew that the attack was coming imminently because we had been warned by the State Department. Even the President called the president of the network and strongly recommended that we get our people out of Baghdad, but I made the decision that — as long as they would volunteer to stay — that they could stay. “This is the greatest scoop in the history of journal- ism!”

-Ted Turner on Gulf War. We were freedom of the press, we were going to get the story. I was in Jane Fonda’s room. She was working, and I had the afternoon off, and it was, I don’t know, about 5:00 or 6 o’clock East Coast time and two o’clock West Coast, and I was watching CNN, and the war started. I flipped over to KCBS and Dan Rather was in the studio talking, and I flipped over to NBC and Tom Brokaw was in the studio talking, and I flipped over to ABC and Peter Jennings was in the studio talking, and I flipped over to CNN, and the tracer bullets were going and the rockets were getting shot down, and I said, ‘Yippee! This is the greatest scoop in the history of journalism!’ And it still is the greatest scoop, and one network had the start of the war from behind enemy lines…”

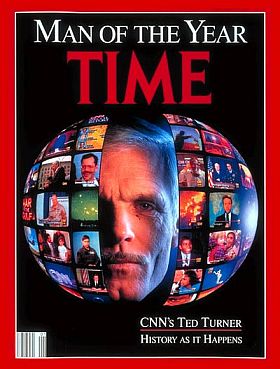

CNN, in fact, soon became a daily staple for most government leaders, and even became a go-between in some cases of diplomacy. Even the Pope’s counsels consulted the channel, reported Time magazine, “to know what to pray for.” In January 1992, a major recognition came for Turner when Time magazine placed him and his network on the cover of its “Man of the Year” issue. CNN’s global growth meanwhile, continued to climb. By 1995, it had 156 million subscribers in 140 countries.

Time magazine’s ‘Man of the Year’ edition, January 6, 1992, featuring Ted Turner & CNN – ‘History as it Happens’. Click for copy.

In the media business that summer, it was a crazy time. All the major players, it seemed, were sizing up each other; big deals were flying everywhere. Disney that August had become the world’s largest media company after it acquired Capital Cities/ABC for $19 billion. And soon thereafter, the ground shifted for Turner as well as the Big Media sights were turned on Turner Broadcasting.

Time-Warner Deal

Time Warner — the media giant that was itself created in the 1989 merger of Time, Inc. and Warner Communications — had been eyeing Turner Broadcasting for some time. Already holding a board seat at Turner Broadcasting, Time-Warner had blocked Turner from acquiring NBC. Gerald Levin, the CEO of Time-Warner, had been interested in owning Turner Broadcasting since the late 1980s. But after Disney upped the ante among big media players with its 1995 Cap Cities/ABC deal, Turner became even more attractive to Time-Warner.

Turner would become part of Time-Warner.

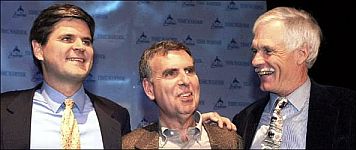

Sept 1995: Ted Turner with Time-Warner chairman Gerald Levin as the two men held a press conference in New York on their planned merger. Background panels display the logos of the various Turner and Time-Warner companies that would come together in the new media giant.

Still, some wondered why Ted Turner would make the deal, or that he would be comfortable as Vice-Chairman after years of being the guy in charge. Others, however, saw a less frenetic Turner and one with new interests. “Do not discount the influence of Jane Fonda,” explained a former Turner confidant to Time magazine in September 1995. “There is no question she has mellowed him. His blood pressure is down. He’s closer to his children than before. He dresses better. He leaves the running of the business to his team so he can do his projects: the women’s movement, the environment and raising buffalo. He spends only two or three days a month at TBS. Otherwise, he is out buying the West.” Turner by then had become a major U. S. landowner, with property in Montana, New Mexico and elsewhere. Yet the media business was still a major part of who he was. But some wondered if his reduced role at Time-Warner would be enough. For the next few years, Turner became an active player in the Time-Warner world — but no less controversial.

“Ted’s Excellent Idea”

Ted Tuner, an early advocate of the wealthy giving away their fortunes for good causes, appears on Newsweek’s cover of September 1997 for his $1 billion gift to the United Nations, with tagline: “I’m putting the rich on notice.” Click for copy.

Richard Hack’s book on battles between Ted Turner and Rupert Murdoch, 'Clash of the Titans'. Click for copy.

Meanwhile, back in the mid-1990s, from his new perch at Time-Warner, Ted Turner ignited a war of words with another media mogul — Rupert Murdoch, head of the up-and-coming Fox Network. At one point Turner boasted that Time-Warner would squash Murdoch in the media wars. By October 1996 Murdoch had invested more than $100 million in the Fox News Channel — much of it on cable operators to distribute the program to millions of homes. Time-Warner declined to carry the Fox channel on its New York City cable system, bringing the dispute to the fore in the New York media. Murdoch had long criticized CNN for its “liberal” news coverage. Back-and-forth news stories on the squabble continued through 1996 and 1997. At one point, Turner even challenged Murdoch to a Las Vegas boxing bout, in which the loser would have to leave the country. Murdoch declined. But in June 1997 Time-Warner agreed to carry Fox News on its cable system and provide Fox access to other Time-Warner systems as well. However, the Turner-Murdoch feud surfaced again in 1998 when Murdoch acquired the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team and Turner, a team owner, sought to block Murdoch. Murdoch’s New York Post meanwhile, in later stories covering CNN layoffs in 2000 and 2001, included illustrations that mocked CNN as the “Cheap News Network” and “Cruel News Network.” However, some years later, Murdock and Turner called a truce after Turner invited Murdock to lunch where they reportedly buried the hatchet. But in his business career, Ted Turner had other problems that came with the changing landscape of Big Media in the year 2000.

AOL Time-Warner Deal

January 2000: Steve Case, Gerald Levin and Ted Turner at announcement of the AOL/Time-Warner merger.

Ted Turner became an enthusiastic supporter of the merger when it first occurred. But soon, the long knives came out, and Ted Turner was sent to the sidelines.

Turner remained on the company’s board of directors and kept his title of vice chairman, but AOL Time Warner head Gerald Levin took away Turner’s control of Turner Broadcasting. That fall, Turner said, as later reported, “I never in my wildest dreams thought I would lose my job.”

|

Turner, The Enigma They didn’t call him the “mouth from the South” without basis. Fact is, Ted Turner’s gaffes would get him into trouble more than a few times. But “warts and all” is part of the Ted Turner package. Wrote Time reporter William A. Henry, III in 1982: “If Turner were a character from Shakespeare — and he has that kind of incandescence — he would be in equal parts the nobly ambitious Prince Hal, the impulsively belligerent Hotspur and the comically self-indulgent Falstaff.” Henry also noted that Turner “has a genuine love of risk and an abiding faith in the value of competition, win or lose. He trusts his own vision and scorns prudent measures like market research. He loves to cast himself as a hapless crusader or starry-eyed underdog, and revels in emerging as the triumphant idiot savant.” Turner’s gaffes and offensive blunders are typically followed by apologies. He can’t help himself, it seems. But even when he’s wounding someone it’s often unintentional, made more out of bluntness than malice. For there is a core decency in Ted Turner; he is a well-intentioned soul trying to make a difference and wanting approval for the effort. |

Yet in some ways, Ted Turner was his own worst enemy. Not everyone, it turns out, felt comfortable with him as a business associate, especially given his penchant for unguardedly speaking his mind. His occasional gaffes may have contributed to his being shunted aside in the aftermath of the AOL deal.

In March 2000, Turner attended a meeting with CNN staffers that included some Catholic employees who had ash marks on their foreheads in observance of Ash Wednesday. Turner at first thought the ash marks were dust and grime on those then covering the Seattle earthquake. But then he remembered it was Ash Wednesday and said, “I realize you’re just Jesus freaks.” Then he added, “shouldn’t you guys be working for Fox?,” in reference to the conservative Fox News Channel.

Turner later apologized for the remarks, but they were reported by the Fox News Channel and the front page of Rupert Murdoch’s New York Post. Some Catholic groups reacted angrily while AOL officials got their first dose of the free-swinging Ted Turner.

Earlier in his career at Time-Warner, Turner had also made remarks many considered offensive: calling Christianity “a religion for losers;” making a derogatory remark about Poles and the Pope; citing the 1997 Heaven’s Gate cult suicides of 39 people as “a way to get rid of a few nuts;” and calling opponents of abortion “bozos.”

Said one company official about Turner’s penchant for insult: “Look, with Ted you get a lot of great, big thoughts. You get a great spirit, and you get a really smart guy. But you also get somebody who from time to time says whatever he happens to be thinking at the moment. Whether he thinks it tomorrow isn’t necessarily the case, but that’s the whole package.”

Others had observed the contradictions before; finding a guy, especially in his early years, who could be vulgar and abusive to his colleagues, yet deeply loyal to them; a womanizer who once bragged about his photographs of nude women, yet deplored the decline of family values and nudity and sex on film and TV; a man who was sometimes careful and guarded, but then embarrassingly blunt or crassly to-the-point.

Moving On

Frustrated with his gradual loss of power at the new AOL Time-Warner and lack of a meaningful role, Ted Turner began looking for other ways to hedge his bets and use his still-creative energies. In June 2001, though still with AOL Time-Warner, he set up a new production company in Atlanta called Ted Turner Productions; a venture to produce feature-length films and documentaries.Turner later said that one of his biggest regrets was selling his empire to Time-Warner in 1996. In November that year, looking back on mistakes made, Turner told cable industry executives gathered in Anaheim, California that one of his biggest regrets was selling his empire to Time-Warner in 1996. Rather, he said, Turner Broadcasting should have acquired Time-Warner. Then, he said, “I could have fired Gerry Levin before he fired me.” Still, in late December 2001, Turner agreed to remain on the Time-Warner AOL board for a few more years. He was then the company’s largest individual stockholder, owning about 4 percent of its shares. As of August 2002, Turner held 138 million AOL Time-Warner shares. However, in the ensuing years he would lose billions of dollars in personal wealth during the high-tech bust as AOL Time-Warner deflated from its lofty values and unrealistic expectations.

Jane Fonda & Ted Turner in happier times; they separated in January 2000 and later divorced, though Turner still calls her the love of his life. Photo, Robin Platzer. Click for separate story on Jane Fonda.

He began raising bison on the some of the land, and in 2002, he co-founded Ted’s Montana Grill, a restaurant chain specializing in bison meat (50 restaurants now operating in more than 28 states).

He had also set up, and became actively engaged with, various philanthropies focused on endangered species, environmental issues, world peace, and the threat of nuclear weapons. In February 2006, he formally resigned from the AOL Time Warner board. In November 2008, a biography, Call Me Ted, was released, joining a number of others from earlier years (see Sources below).

Bragging Rights

Regardless of what some critics might say, Ted Turner has fair claim to some braggadocio, especially given what he’s accomplished and how far he’s come: “I started with virtually nothing,” he explained in a 2007 interview. “In 1970, which was my first year in the television business, we had 35 employees at the station in Atlanta, and we did $600,000 in business…. There was usually a higher purpose in what he was about; a well-intended end of some kind.When I merged with Time-Warner in 1995, which was 25 years later, we had 12,000 employees, and we did two-and-a-half billion dollars. Instead of losing a million dollars, which we did the first year, we made close to $250 million profit, and that was in 25 years.”

And despite his shortcomings in the social graces at times, Turner has, on balance, made the world a better place through both his philanthropy and his inventiveness in the news and entertainment business. There was usually a higher purpose in what he was about; a well-intended end of some kind. In July 1997, as he and CNN were being recognized for their accomplishments at the Liberty Medal award ceremony, Turner explained how he and CNN regarded their news gathering and reporting: “My idea was, we’re just going to give people the facts…We didn’t have to show liberty and democracy as good, and show socialism or totalitarianism as bad. If we just showed them both the way they were…clearly everybody’s going to choose liberty and democracy.”

When boycotts threatened the Olympic Games, Turner launched the Goodwill Games in 1986.

“…[W]hen I merged with Time-Warner it was partly because I was tired. Also, I didn’t think I had enough cards to win the game [emphasis added]. There was going to be, as we’ve seen with Viacom and Disney and NBC, more and more consolidation in the business, and either you were one of the big players or you were going to be marginalized. And I thought merging with Time Warner –our assets were very complementary. I thought that the merger made lots of sense, and it did. The stock price tripled. We all got rich on the Turner/Time-Warner merger. That was the best merger in history….”

But Ted Turner was never about the money, or the awards — of which there have been many, among them, 42 honorary degrees from places like Brown University, Morehouse College, and The Citadel. He also holds some 176 sailing trophies and his smiling face has appeared on the covers of more than 100 magazines over the years. But Ted Turner was really aiming at something else.

On A White Horse

A 1998 book written about Turner’s involvement with the Goodwill Games and some of his other causes is titled Riding a White Horse. That image perhaps best captures the vision Ted Turner had set for himself. Hoping one day to have become a giant media tycoon — parlaying his Turner Broadcasting empire into the entity that would have eaten and conquered CBS or some other colossus. And then, from that perch as top media mogul, with more wealth and influence than ever flowing his way, he, “Ted the Beneficent,” would then be positioned to help solve all manner of the world’s problems.

True, “the man on the white horse” fell short of that, but he has made his mark in generally good and lasting ways. He has given away a great deal of his wealth — proportionately well beyond what most others reaching those heights ever give. And he has set things in motion and provided models that will live long after he has passed on. Along the way, he also changed the business of news and entertainment, mostly for the better. He didn’t do it by himself, of course, as there were dozens of talented people around him. But he did supply the vision, the grit, and the determination to keep things moving forward. And for that and more — especially the constructive changes he brought to the business of news, information and entertainment, enabling millions to be informed in new and beneficial ways — the world owes Ted Turner a debt of thanks. …And he may not be finished yet.

For additional stories at this website on Business & Society, please see that category page, and for film history, the Film & Hollywood page. For story choices in the 1980s or 1990s, scroll to those respective decade options in the “Period Archive” in the upper right-hand corner of this page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

________________________

Date Posted: 29 November 2008

Last Update: 2 August 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Ted Turner & CNN, 1980s & 1990s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, November 29, 2008.

_____________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Ted Turner websites.

“Interview: Ted Turner, Founder, Cable News Network,” Academy of American Achievement, Washington, D.C., October 20, 2007.

PBS-Television, They Made America: “Rebels,” (Two 21st-century American media entrepreneurs, Ted Turner and Russell Simmons), TV series, WGBH, Boston, MA, 2004.

Charlie Rose.com interview with Ted Turner, and also, interview with Ken Auletta on Ted Turner.

“Ted Turner,” “CNN,”and “WPCH-TV,” Wikipedia.org.

“Yachtsman Turner Purchases Braves; Yachtsman Buys Braves For at Least $10 Million,” New York Times, Sports Section, Wednesday, January 7, 1976, p. 59.

“Turner Is Reported Set to Buy Hawks,” Washington Post, December 28, 1976, p. D-16.

Christian Williams, “Super Station’s Super Man,” Washington Post, February 11, 1979, p. M-1.

Christian Williams, “Horatio Alger by Way of Buck Rogers – Satellite Madness,” Washington Post, February 11, 1979, p. M-3.

“Ted Turner’s Nonstop Gamble: CNN Sets Sail,” Washington Post, June 2, 1980, p. D-1.

Associated Press, “Turner Wins Satellite Suit,” New York Times, Wednesday February 11, 1981, p. D-10.

Reginald Stuart, “He’s Getting Interference, 1970-1981,” New York Times, Sunday, September 13, 1981, Financial, p. 6.

Tony Schwartz, “CBS and Turner Differ on Talks,” New York Times, October 16, 1981.

Philip H. Dougherty, “Advertising; Cable TV Doing Well In Commercials,” New York Times, December 8, 1981.

Tony Schwartz, “Turner Opens 2nd Network in Cable-News War,” New York Times, Monday, January 4, 1982, p. C-17.

Associated Press, “Turner Broadcasting Reports $5.3 Million Loss in Quarter,” New York Times, May 16, 1982.

Philip H. Dougherty, “Advertising; ‘Nonstop News Machine’,” New York Times, June 18, 1982.

William A. Henry, III, “Shaking Up the Networks,” Time (cover story), Monday, August 9, 1982.

Tony Schwartz, “Cable TV Programmers Find Problems Amid Fast Growth,” New York Times, September 28, 1982, p.1 .

Sally Bedell, “Ted Turner Challenges TV Networks,” New York Times, October 17, 1982.

Merrill Brown, “Ted Turner’s TV Dream Edges Toward Profit – After Years in the Red, TBS Verges on Being Profitable,” Washington Post, April, 24, 1983, p. F-1.

Sandra Salmans, “Television’s ‘Bad Boy’ Makes Good,” August 14, 1983, New York Times, Business Section, p. 1.

Sally Bedell Smith, “Turner Buys Sole Rival in Cable News Market,” New York Times, October 13, 1983.

Maynard Good Stoddard, “Cable TV’s Ted Turner: Spirited Skipper of CNN,” Saturday Evening Post, March 1, 1984.

Merrill Brown, “Ted Turner Plans Bid For ESPN,” Washington Post, April 7, 1984, p. D-9.

David A. Vise, “Turner Discussed CBS Bid With Sen. Helms,” Washington Post, March 20, 1985, p. A-1.

David A. Vise, “Turner Reveals Offer for CBS, Initiates Suits,” Washington Post, April 19, 1985, p. A-1.

Eleanor Randolph, “Turner Built Empire Bucking Establishment — ‘He Shouldn’t Be Underestimated’,” Washington Post, April 19, 1985, p. F-1.

Daniel Schorr, “Ted Turner Is Crazy Like a Fox,” Sunday Outlook Section, Washington Post, April 21, 1985, p. K-1.

David A. Vise, “Ted Turner To Buy MGM/UA – 2 Movie Studios’ Assets to Be Split In $1.5 Billion Deal,” Washington Post, August 6, 1985, p. C-1.

David A. Vise, “Turner Drops Hostile Bid for CBS,” Washington Post, August 8, 1985, p. E-3.

Nell Henderson, “Turner Says No to NBC’s Bid for CNN,” Washington Post, November 22, 1985, p. D-8.

Michael Schrage and David A. Vise, “Murdoch, Turner Launch Era of Global Television — Deregulation, Technology Help in Reshaping Industry Relaxation Of Rules In Europe A Boon to Turner, Murdoch,” Washington Post, August 31, 1986, p. H-1.

David A. Vise and Michael Schrage, “Murdoch, Turner: A Study in Contrasts — Pursuit of Common Goal Elicits Different Styles; Both Men Willing To Take Colossal Risks,” Washington Post, September 7, 1986, p. H-1.

Andrew Rosenthal, “Washington Talk: The News Media; Watching Cable News Network Grow,” New York Times, December 16, 1987.

Milton Moskowitz, Robert Levering, and Michael Katz, “Turner Broadcasting,” Everybody’s Business: A Field Guide to the 400 Leading Companies in America, Doubleday: New York, 1990, pp. 354-355.

Jerry Adler, “Jane and Ted’s Excellent Adventure,” Esquire, February 1991.

William A. Henry III, Anne Constable, Michael Duffy, William Tynan, “History As It Happens,” Time, Monday, January 6, 1992.

Robin Berger, “Castle Rock Purchase Costs Turner Broadcasting System $100 Million,”Los Angeles Business Journal, August 23, 1993.

Porter Bibb, Ted Turner: It Ain’t As Easy As It Looks, New York: Crown Publishers, 1993.

Edmund L. Andrews, The Media Business; “Angry Turner Says He Wants NBC,” New York Times, September 28, 1994.

“Turner May Weigh CBS Bid, NBC Says,” New York Times, August 8, 1995.

Geraldine Fabrikant, “In Quest of CBS, Turner Meets Microsoft Chief,” New York Times, August 14, 1995.

Geraldine Fabrikant, “Microsoft Seen Weighing $1 Billion Turner Stake,” New York Times, August 23, 1995.

“Turner Can’t Get a Grip on CBS,” Business Week, September 4, 1995.

Richard Corliss, “Time Warner’s Head Turner,” Time, Monday, September 11, 1995.

Mark Landler, “Time Warner Sets $8.5 Billion Offer for Turner Cable,” New York Times, August 30, 1995.

Maureen Dowd, “Ted’s Excellent Idea,” New York Times, August 22, 1996.

Ted Turner Remarks, Liberty Medal Award Ceremony, July 4, 1997.

Althea Carlson, Riding a White Horse: Ted Turner’s Goodwill Games and Other Crusades, Episcopal Press, 1998, 272 pp.

Michael J. Wolf, The Entertainment Economy: How Mega-Media Forces Are Transforming Our Lives, New York: Times Books/Random House, 1999, pp.122-123.

Jim Rutenberg, “MediaTalk; AOL Sees a Different Side of Time Warner,” New York Times, March 19, 2001.

Jim Rutenberg and Alessandra Stanley, “At 63, Ted Turner May Yet Roar Again,” New York Times, December 16, 2001.

Ken Auletta, “Q. & A.: Journalists and Generals,”(Ted Turner interview), The New Yorker, March 31, 2003.

Richard Hack, Clash of the Titans: How the Unbridled Ambition of Ted Turner and Rupert Murdoch Has Created Global Empires that Control What We Read and Watch Each Day, 2003, New Millennium Press.

Reese Schonfeld, Me and Ted Against the World: The Unauthorized Story of the Founding of CNN, New York: HaperCollins, 2001, 432 pp.

Ted Turner, “My Beef With Big Media,”Washington Monthly, July/August 2004.

Gary Shapiro, “Tuning in to Ted Turner at the Y,” New York Sun (NYSun.com), September 30, 2004.

Ken Auletta, Media Man: Ted Turner’s Improbable Empire, Atlas Books, 2004.

Steve Hargreaves, “Ted Turner Exiting Time-Warner Board,” CNNMoney.com, February 24, 2006.

HachetteBookGroup.com, Website feature on 2008 Ted Turner biography, Call Me Ted, which included a slide show on Turner’s life and a short video of Turner with author, Bill Burke.

____________________________________