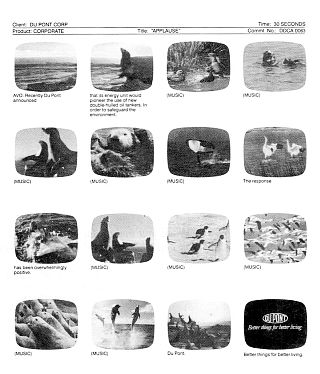

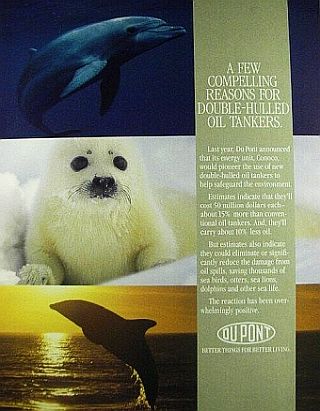

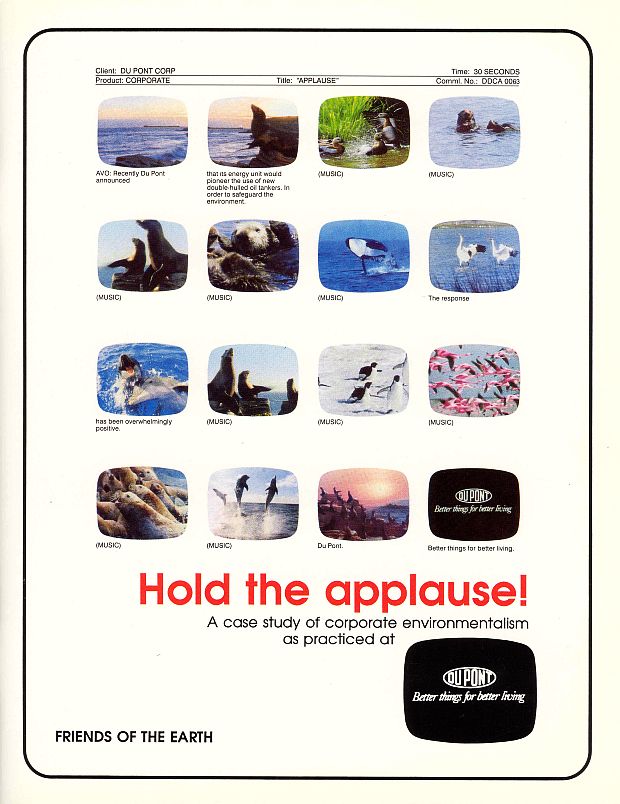

In 1990, Du Pont, one of the world’s largest chemical companies, began running a TV ad featuring a series of beautifully-photographed sea lions, otters, dolphins, penguins, and flamingoes choreographed to Beethoven’s Ode to Joy, all cast in natural settings. The ad, shown below, appeared to depict marine mammals and wildlife “celebrating” Du Pont’s news about its then proposed double-hulled oil tankers for its Conoco oil subsidiary. Titled “Applause,” the ad, with its flipper-clapping seals, jumping dolphins, and barking sea lions, offered seeming approval of Du Pont’s promised protection from oil spills. The ad ran repeatedly from 1990 through 1992, along with a similar print ad. But Du Pont’s ad came at a notable time in the nation’s environmental history and generated a bit of controversy, given the company’s history of pollution and chemical troubles.

In Washington, D.C,, meanwhile, Friends of the Earth, a national environmental group, was not amused, and decided to produce a critique of the ad and the company’s environmental record. More on that report and its media coverage a bit later. First, a quick recap of the ad’s message.

At its opening, the viewer is looking out over a coastal shoreline to the far horizon where ocean meets sky, and there, barely visible in the late afternoon light, is a distant sliver of an oil tanker on the water. “Recently,” begins the narrator as a lone sea lion on a rocky shore looks out on the ocean, “Du Pont announced that its energy unit, Conoco, would pioneer the use of new double-hulled oil tankers in order to safeguard the environment.”

Then comes the feel-good Beethoven score backing the sequence of frolicking water fowl and marine mammals – floating ducks flapping their wings, a sea otter swimming playfully on its back, sea lions clapping their flippers, etc. “The response…,” continues the narrator as a pair of Whopping Cranes join the celebration, “has been overwhelmingly positive.” Some approving dolphins then flash to view. Ode to Joy revs up once again behind more shots of sea lions, penguins, flamingos on the wing, and jumping dolphins.

A group of barking and “clapping” sea lions join in the celebration near the end of Du Pont’s “Applause” TV ad.

Save for this ending, the ad could almost pass for a piece by the Audubon Society or World Wildlife Fund. And that’s the point. Known in the ad trade as a “corporate” piece, Du Pont was trying to drape itself with environmental imagery; trying to create an environmentally-positive corporate image.

Du Pont by then, was a corporate colossus, a giant chemical and oil company, having acquired Conoco a decade earlier. Here’s some history on that deal and how Du Pont also began to shape a new environmental image for itself.

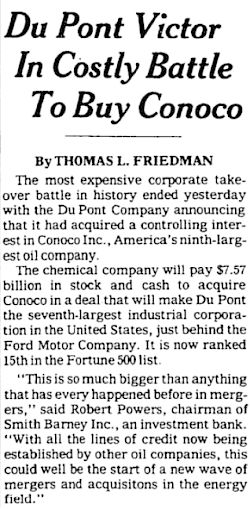

Aug 1981 front-page New York Times story on Du Pont acquisition of Conoco for .57 billion.

The 1980s

Du Pont-Conoco Deal

In August 1981, about a decade before Du Pont’s cleaver TV ad appeared, Du Pont had acquired the Conoco oil company – formerly known at the Continental Oil Company – for $7.57 billion. Conoco at the time was the nation’s ninth-largest oil company and its second-largest coal producer (having itself acquired Consolidated Coal Co. in 1966).

The Conoco deal made Du Pont the seventh- largest industrial corporation in the U.S., just behind Ford Motor Company. This deal occurred in the heady days of 1980s merger mania and corporate raiders, as Conoco was then besieged by other corporate giants– Seagram, Texaco, and Mobil, among them. Du Pont was seen as a friendlier potential partner, or in the parlance of the corporate takeover frenzy, a “White Knight”.

A silver lining for Du Pont was that it now had an in-house supply of oil, thought to be an advantage for a chemical maker whose products used hydrocarbons as their raw material. In any case, Du Pont was now a major oil company and a major chemical company. It now owned, oil wells, gas stations, oil refineries, and oil tankers.

Exxon Spill. But in the years that followed, operating oil tankers on the high seas came in for some intense scrutiny, especially after the Exxon Valdez supertanker ran aground in Alaska’s Prince William Sound on March 24, 1989, spilling 11 million gallons of crude, badly fouling Alaska’s environment, wildlife, and salmon fisheries. Eventually 1,300 miles of coastline were hit by the spill.

The Exxon spill was then the largest in U.S. history, and touched off a round of public outrage, renewed environmental fervor, and calls for tougher regulation. For weeks and weeks, the spill and its difficult clean-up was an ongoing news story, with indelible images of oil soaked sea otters, seals, and seabirds, while an army of yellow-clad workers did their best trying to clean up the oil along rugged Alaskan coastlines. The Exxon Valdez tanker was a single-hull vessel, and a U.S. Coast Guard study at the time had found the spillage would have been reduced 25-to- 60 percent if it had a double hull. Exxon, meanwhile, would become engaged in protracted litigation on a number of fronts; court battles that would go on for years.

1989. For weeks and weeks, following the Exxon Valdez supertanker spill, an army of workers clad in yellow and red protective gear, did their best trying to clean up the oil along rugged Alaskan coastlines.

But in 1989-90, especially given the spill and the upcoming 20th anniversary of Earth Day that April, oil and the environment were uppermost in the national mind. A group of investors and environmental leaders would soon form an alliance and put forward a corporate code of conduct called “The Valdez Principles,” challenging corporate leaders to commit to improved environmental performance (though not released until September 1989). Du Pont, it turned out, was already thinking along those lines – at least in part.

The Woolard Speeches

Corporate Environmentalism

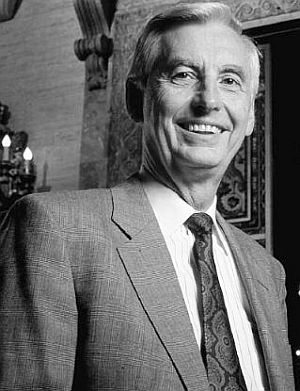

On the heels of the Exxon Valdez spill and the approaching Earth Day 1990 celebration, Du Pont began to attempt an environmental makeover – at least in principle. On May 4th, 1989, less than two months after the grounding of Exxon’s tanker, incoming Du Pont CEO, Edgar Woolard, delivered an address to the American Chamber of Commerce meeting in London. The topic of Woolard’s speech: “Corporate Environmentalism,” a concept he is credited with inventing.

Ed Woolard, Du Pont Chairman & CEO, circa early 1990s.

“Environmentalism is the mainstream,” he said. “…Our continued existence as a leading manufacturer requires that we excel in environmental performance and that we enjoy the non-objection –indeed even the support — of the people and governments in the societies where we operate….”

Du Pont and Woolard were trying to stake their claim to the moral high ground of environmental protection, stating that they would move in a progressive direction with pro-active, pro-environment policy. And through 1989 and 1990, Woolard would continue to deliver variations of his corporate environmentalist pledge. In December 1989, he spoke at the World Resources Institute in Washington, D.C. and in late January he addressed the National Wildlife Federation’s “Synergy ’90” conference, also in Washington.

At an October 8th, 1990 meeting of the Society of Chemical Industry in Monte Carlo, Woolard stated: “The future of the chemical industry will be directly shaped — and indeed may ultimately be determined — by environmental issues.” There, he also warned his business colleagues, noting that “society won’t tolerate” companies that “drag their heels indefinitely on environmental problems…” And at the Detroit Economic Club in November 1990, he advised his listeners that the environmental impact of their product or service – as it is produced, while it is used, and after its useful life is over – had to be “thought out before the first sale is even made.” Companies that do well addressing environmental problems with real commitment, he suggested, could also gain a competitive advantage. Elsewhere in Du Pont, its oil subsidiary, Conoco, was also touting the new environmental line.

Double-Hulled Ships

Pamphlet with April 1990 remarks of Conoco’s CEO outlining company’s environmental initiatives, including plan for double hulls on its oil tankers.

Conoco’s Tankers

In advance of Earth Day 1990 that April, Conoco CEO, Constantine Nicandros, was putting together a major speech to announce Conoco’s environmental policies, which would be much in line with Du Pont’s, of course, but would also include one special item on oil tankers.

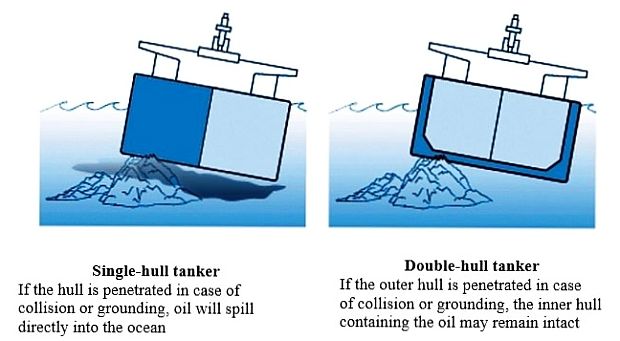

Conoco officials knew that a high percentage of tanker accidents involved side collisions or groundings — accidents in which double hulls could help reduce or prevent oil spillage. And given the fact that the public was then quite concerned about tanker safety in the aftermath of the Exxon spill, Conoco decided to investigate pricing and solicit bids for both double and single hull construction.

Conoco discovered that double-hull construction was only 15 percent more than single-hull construction. And as Robert Walker, Conoco’s Vice President for Supply and Transportation would put it, “anytime you can take care of 80 percent of a potential liability for 15 percent more cost, it’s well worth it… It didn’t make any sense for us not to do it.”

So, about a week before Earth Day, on April, 10th, 1990, Conoco announced it had placed orders for two of its crude oil tankers to be built with double hulls. The announcement came in the speech by CEO, Constantine Nicandros at a news conference in Houston, Texas. As he outlined a list of the company’s nine environmental initiatives, the third item on the list was to “construct only double-hulled tankers in the future,” noting the company had already placed orders for two such ships. The improved construction would give the tankers double sides and double bottoms — inner and outer steel plates, with a space in between them — a design that would absorb the impact of certain kinds of accidents and groundings and help prevent or limit oil spills.

Single-vs. Double-Hull Tankers

Conoco’s announcement, meanwhile, made big news. The New York Times ran its story of April 11, 1989 on its front page with the headline, “Breaking Oil Industry Ranks, Conoco Buys 2-Hulled Ships.” The Seattle Times also noted in its reporting on the Conoco announcement, that its U.S. Senator, Democrat Brock Adams, then pushing for a law requiring double hulls on all U.S. tankers, hailed the announcement as a major breakthrough. “This shows a break in the oil-company ranks,” Adams said on hearing the news. “Conoco is to be commended as a good corporate citizen.”

April 11, 1990, New York times front-page story on Conoco's double hull order.

The Conoco double-hull announcement also preceded a National Academy of Sciences study which planned to examine the economic cost/benefit of double hulls and double bottoms. Conoco’s tanker traffic was then running primarily in the Gulf of Mexico between its production fields in South America to its refinery in Lake Charles, Louisiana.

Genesis of The Ad

Back in Wilmington, meanwhile, Du Pont public relations people saw the media attention the double-hull decision was getting and soon set the wheels in motion for developing a Du Pont TV advertisement to tout the decision. They asked their New York ad agency, BBDO,– Batten Barton Durstine & Osborn – to work up some material for a possible Du Pont double-hull TV ad.

BBDO storyboard showing wildlife shots for proposed Du Pont ad.

Lee Tashjian, then Du Pont’s Vice President for Public Affairs, would recall that the moment he saw the wildlife version, he “knew it was the one we wanted.” Still, “Applause” was pre-tested at shopping malls in a number of cities across the country, along with another proposed spot on the company’s plastics recycling program.

In the testing, “Applause” scored very high in terms of the favorable attitude toward the company,” reported Lee Tashjian. Normally, when 50 percent of a test audience comes away with a “highly favorable” rating of a spot, that is considered very good. “Applause” brought the house down; three-quarters liked it; 25 percent liked it a lot, and only a few disliked it. More than half indicated the commercial improved their opinion of Du Pont, which was “quite outstanding,” according to Tashjian. In fact, some of the viewers indicated the ad made them “feel better about the company” — which is exactly what the public relations people were looking for.

One of the opening frames from Du Pont’s 1990 “Applause” TV ad, with a barely visible oil tanker on the horizon.

“Estimates indicate,” claims Du Pont in this 1991 print ad, that double-hulled oil tankers “could eliminate or significantly reduce oil sills, saving thousands of sea birds, otters, seal lions, dolphins and other sea life.”

The text in this ad, like the TV ad, first explains that Du Pont’s Conoco unit has announced it would “pioneer the use of new double-hulled tankers to help safeguard the environment.” Then it adds some economics about the new tankers: “Estimates indicate that they’ll cost 50 million dollars each – about 15% more than conventional oil tankers. And they’ll carry about 10% less oil.”

And finally, there is a generic claim about wildlife saved: “But estimates also indicate they could eliminate or significantly reduce the damage from oil spills, saving thousands of sea birds, otters, sea lions, dolphins and other sea life” (emphasis added). The ad’s conclusion – in this case, without the sound effects of the TV ad’s barking sea lions and the Beethoven score – “The response has been overwhelmingly positive.”

But for Friends of the Earth, the Du Pont advertising was viewed as both misleading and a major diversion from Du Pont’s actual environmental record — particularly on pollution, toxic waste, and stratospheric ozone damage. So the group soon decided to prepare a critique of the ad and company, including the Woolard speeches. At the time, Friends of Earth (which had recently merged with the Environmental Policy Institute and The Oceanic Society), was already engaged with Du Pont in the shareholder arena, working with an individual stockholder who agreed to propose a March 1991 shareholder resolution calling on Du Pont to adopt a 1995 phase-out of ozone-degrading CFCs. Du Pont was then the largest producer of those chemicals, and viewed as dragging their feet on a phase out. Du Pont fought the proposed resolution from shareholder Amelia Roosevelt. Friends of the Earth, supporting Roosevelt, backed litigation to have the resolution offered, but that issue then went to the courts.

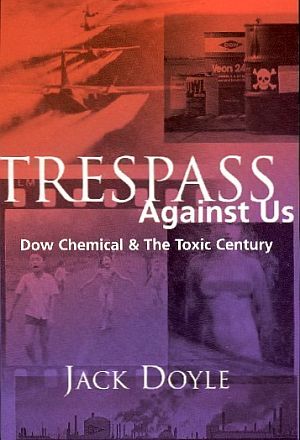

Meanwhile, in the late spring of 1991, with the backing of Friends of the Earth President, Mike Clark and VP’s Brent Blackwelder and Jim Lyon, work began on a report focused on the “Applause” TV ad and Du Pont’s environmental record. FOE’s corporate analyst, Jack Doyle, would research and write the report with the help of other staff experts, including, in particular, Liz Cook on ozone policy and Tom Bethell for editing and publishing. Doyle and Cook would also continue work on the shareholder resolution and later met with Du Pont officials on that issue.

Ad Critique & Report

Hold The Applause!

By mid-August 1991, a 112-page monograph titled, Hold the Applause! A Case Study of Corporate Environmentalism as Practiced at Du Pont, was prepared by Friends of the Earth, using the color version of the BBDO storyboard as the report’s cover. The carefully-written report — with 12 sections and nearly 250 endnotes — was released at a press conference held at the National Press Club in Washington on August 27th, 1991, where FOE’s Blackwelder and Doyle introduced the report, made opening statements, and took questions.

Friends of the Earth’s report on Du Pont by Jack Doyle, “Hold The Applause!”, a 112-page critique of the company's TV ad and environmental record. The report was released on August 27th, 1991 at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. Click for copy.

As introduction, the report gave a narrative description of the ad for readers, as well as the recent history of environmental speech-making by Du Pont’s Woolard. Then it took the company to task for what it said and did not say in the “Applause” TV ad.

None of Conoco’s oil tankers at the time the ad was running had double hulls. The two 95,000-ton tankers then ordered from South Korea’s Samsung Group would not be in the water for nearly two years (until March 1992 at the earliest). But the ad did not state that. Nor did the ad mention that Conoco’s “petroleum fleet” was then one of the smallest in the oil industry at a total of six vessels, especially when compared to Exxon’s 170 or Shell’s 150 tankers. The remaining four Conoco tankers were not then scheduled to be double hulled until the year 2000, then nearly a decade away.

“Clapping” sea lions from Du Pont's “Applause” TV ad of 1990-92, though not found in the Gulf of Mexico.

Du Pont also claimed that Conoco would “pioneer” the use of double hulls. However, putting double hulls on tankers wasn’t a new idea. In fact, double hulls had by that point been used on tankers transporting other hazardous chemicals for more than 20 years. In the U.S. maritime fleet of ships used to transport other chemicals, at least 40 of 150 tankers then had double hulls or double bottoms. In fact, even in the petroleum industry, there had been double-hull tankers in use for transporting oil prior to Conoco’s announcement. Conoco, however, claimed the first such “modern” tankers. Still, Conoco wasn’t “pioneering” the use of double-hull tankers.

Conoco also then owned and operated two “commercial trade” supertankers that transported oil for others under contract, but these were not double hulled, nor were they then part of Conoco’s plan for outfitting tankers with double hulls.

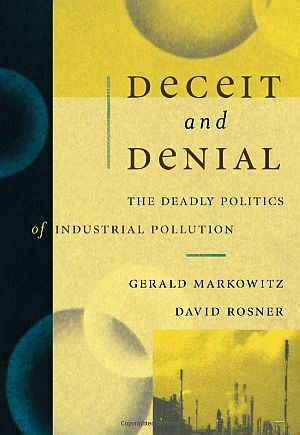

Du Pont’s Pollution

But perhaps the hardest hitting parts of the Friends of the Earth report were the sections that honed in on Du Pont’s pollution, ozone damage, and toxic wastes. Using the company’s then most recently reported air and water pollution data to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI), Du Pont in 1989, was the nation’s single largest corporate polluter. In that year, Du Pont and its subsidiaries reported 348 million pounds of pollutants discharged to land, air and water. And in 1989, Du Pont’s total discharge was approximately 10 million pounds more than it was in 1988.

|

Hold The Applause! Introduction 1. Cue The Seals |

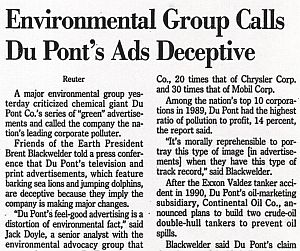

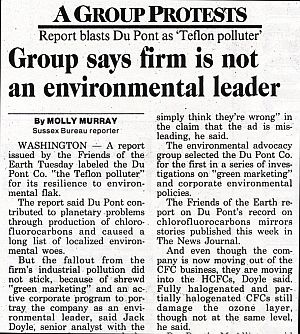

So, as the report was introduced at the National Press Club, FOE’s acting president, Brent Blackwelder and senor analyst Jack Doyle, contrasted Du Pont’s pollution numbers with the imagery put forward in the Applause ad. “The net effect of this ad,” said Blackwelder, “is to mislead the public about Du Pont’s role in the environment.” Doyle took it one step farther: “Using seal pups and dolphins to gloss over” the company’s pollution was “disingenuous and misleading.”

Du Pont’s toxic releases, in fact, totaled more than the combined releases of Allied Chemical, Ford Motor, and Union Carbide put together. Du Pont had 14 times more pollution and waste than Dow Chemical, 20 times that of Chrysler, and 30 times that of Mobil — companies that also ranked among 1989’s top U.S. polluters.

Hold the Applause! noted that Du Pont’s TRI data – large as it was – offered an incomplete picture of Du Pont’s pollution, since only 321 of the roughly 60,000 chemicals then in use were covered. Nor were Du Pont’s numbers independently audited.

In addition, Du Pont was then disposing its toxic pollutants and chemical wastes using somewhat less-visible deep-well injection and high-temperature incineration – techniques not as well understood or as strictly regulated as other methods of disposal. Du Pont operated 39 Class I hazardous waste wells in the U.S. receiving some 30 different kinds of chemicals – 254.9 million pounds in total – much of it acutely toxic. A Du Pont hazardous waste incinerator, not far from New Orleans, was then burning some 21.9 million pounds of wastes a year from 32 Du Pont facilities in 17 states and Puerto Rico.

But Du Pont’s pollution numbers in the Toxic Release Inventory, were only part of Friends of the Earth’s review of Du Pont’s environmental performance history.

1986 NY Times story on ozone degradation, first theorized in 1974, implicating CFCs & Du Pont.

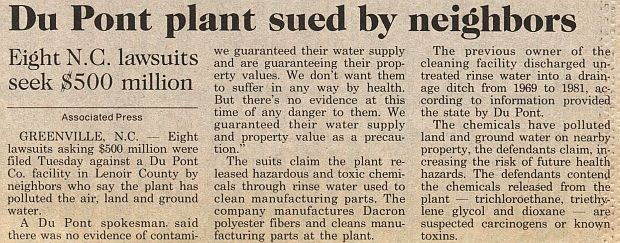

Data from EPA in the report also showed 50 toxic waste sites in 24 states in which Du Pont and/or Conoco were listed as a “potentially responsible parties” for Superfund clean-ups. Du Pont and/or Conoco facilities were also found polluting local communities — titanium tetrachloride releases from a Du Pont plant at DeLisle, Mississippi, and sulfur dioxide and sulfur trioxide from Conoco’s Westlake Refinery at Lake Charles, Louisiana.

Du Pont’s Atlantic Ocean dumping of iron acid wastes from titanium dioxide manufacturing for nearly 20 years (1968-1987) was also documented. Those wastes, which accumulate in sediment where bottom-feeding fish live, contained heavy metals which can cause reproductive problems in fish. Longwall mining by Du Pont’s Consolidation Coal unit in southwestern Pennsylvania was causing surface subsidence beneath farms, homes, parks, streams, roads, and at least one cemetery. Du Pont pesticides benomyl, cyanazine, and its versions of atrazine and synthetic pyrethroids, were then implicated in environmental, public health, and agricultural production problems. And in agricultural biotechnology, the report noted that since 1987, Du Pont had been field testing experimental crops that were genetically engineered to tolerate a new class of chemical herbicides known as the sulfonylureas, a development that Friends of the Earth believed would extend the pesticide era rather than end it.

The “Hot Spots” chapter in Hold The Applause! noted 15 locations – in 13 states plus Mexico and Ecuador – where Du Pont and/or Conoco then had ongoing environmental and/or legal issues, among them: charges of mismanagement and contamination at the Savannah River nuclear weapons complex in South Carolina that Du Pont managed for 30 years; leaking underground gasoline storage tanks at more than 25 Conoco locations in California; lawsuits in North Carolina alleging toxic air, land, and groundwater pollution from a Dacron polyester plant; Conoco oil refinery pollution at Ponca City, Oklahoma and Billings, Montana; and other issues at the Stevens landfill in Bedford, Michigan and dichloromethane emissions at a Towanda, Pennsylvania circuit board plant.

Sample headlines from a 1991 news story about lawsuits filed against Du Pont in North Carolina that alleged pollution from the company’s Dacron polyester plant in Lenoir County, NC. Source: The News-Journal, Wilmington, DE, May 8, 1991, p. D-3.

In the workplace, Du Pont was found to have concealed and withheld asbestos-related disease information during the 1960s for some workers at two of its New Jersey plants, while its Consolidated Coal subsidiary was among companies cited by the U.S. Labor Department for allegedly tampering with coal-dust samples used to protect miners from black-lung disease. And CFC-113, it was learned, posed possible dangers to workers in the electronics industry where the chemical was used as a solvent. Du Pont was also exporting lead additives at the time, containing tetraethyl lead, a known brain toxin to children, even though lead in gasoline was then being phased out in the U.S.

In its political and legislative battles, whether in Washington or various states, Hold The Applause! found Du Pont’s money and muscle at work blocking or weakening environmental laws — from lobbying to weaken the 1980 Superfund law to helping defeat California’s 1990 “Big Green” ballot initiative.

Hold the Applause! also noted that during a 28-month period between March 1989 and June 1991 – approximately the same period when Du Pont and Ed Woolard were touting the company’s new environmental commitments – Du Pont paid out an average of nearly $1 million a month in legal fines, penalties and lawsuit settlements for various environmental, public health and worker safety infractions.

An artist's illustration of some famous Du Pont synthetic fibers & tradenames.

“Green R&D?”

However, Hold The Applause! did recognize and acknowledge Du Pont’s prowess as a prolific inventor and economic power.

The company’s long parade of new wonder products and tradenames made it an economic powerhouse for decades – Nylon, Orlon, Dacron, Lycra, Mylar, Freon, Teflon, Kevlar, Tyvek and more – all “better things for better living.”

Yet some of these “wonder products” were only “wonderful” until the downsides were discovered, sometimes 30-to-40 years later.

For too many years and too many products, Du Pont’s inventive process was not always guided by precaution. The operative paradigm seemed to be “invent-first–and-ask-questions-later.” As Hold The Applause! offered in its final chapter:

…If Du Pont is to make a meaningful contribution toward ameliorating the world’s present polluted condition, it will do so by revolutionizing the research and development process…

One of the reasons why the planet is in trouble today is that when companies such as Du Pont began to put Freon to work, invented nylon, or moved polymer technology forward, there was no corollary environmental science process alongside the R & D effort. There was no institutional mechanism that put products and new manufacturing designs through a gauntlet of environmental checks and tests….

…Corporations such as Du Pont need to fully incorporate biological, public health, product life-cycle, and energy-cost screens into their R& D processes early on, making these considerations as contemporaneous and as important as the hardware, chemistry, and physics of innovation… The challenge to Du Pont and the chemical industry… is simple enough: Do no harm.

August 28, 1991 story appearing in the Washington Post on Friends of the Earth's Du Pont report, “Hold The Applause!”.

Press coverage on Hold The Applause! included stories that appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, Philadelphia Inquirer, Reuters, The News-Journal (Wilmington, DE), Congressional Quarterly, Washington Times, Advertising Age, and others.

The report also prompted at least one editorial, that from the Philadelphia Inquirer on August 30, 1991, noting in part:

“…We recognize that advertisers have a great deal of license to present themselves in the best possible light. But enlisting a host of lovable sea animals in the promotion of a company that remains one of the nation’s most prodigious producers of environmentally dangerous chemicals seems a bit much…”

August 28, 1991. Story appearing in the News Journal of Wilmington, DE on Friends of the Earth's Du Pont report.

Du Pont: “Unfair!”. Du Pont officials, for their part, believed they were being unfairly targeted by the Friends of the Earth report, and that what was revealed was nothing new. “I think the fact that we are a big company, that we are visible and we have tried to provide some leadership … I think that we become an easy target,” said Du Pont spokesman John McAllister in comments to the Philadelphia Inquirer upon the release of the report.

B. W. Karth, Du Pont VP for safety, health and the environment, said the report contained nothing new: “It seems to be a rehash of several of Du Pont’s most serious environmental challenges – all of which we are working diligently to resolve.” Karth also told the National Environmental Digest in September 2, 1991 that the report’s use of the “biggest polluter” tag was not a fair charge, because the largest part of Du Pont’s releases were “hazardous materials disposed of by EPA-approved underground injection,” comprising more than two thirds of Du Pont’s total reportable releases. Karth also claimed that total releases had been cut by 30 percent for the next reporting year, but a July 1991 Wall Street Journal story noted that sizeable reductions in some categories of Du Pont waste for that year were due to EPA reclassifications of certain wastes that didn’t have to be reported, rather than being actual reductions

A copy of Hold the Aplause! had been sent to Du Pont CEO Ed Woolard by Friends of the Earth’s Brent Blackwelder a few days prior to the release of the report at the National Press Club. In his letter to Woolard, Blackwelder noted, “…In the report, we have made 20 recommendations we believe will improve the environmental performance of the Du Pont Company, and we will be pleased to discuss these or any other aspects of the study with you or your staff.” Friends of the Earth also sent the report to major Du Pont shareholders — among them, large pension funds, several universities, and the Ford Foun-dation.

Du Pont officials, including Ed Woolard, would later meet with FOE staff on the ozone issue in early September 1992, but not on Hold The Applause! per se. FOE did receive a courtesy response from Du Pont on the report, but no detailed rebuttal or point-by-point response was received.

Friends of the Earth, meanwhile, would continue pushing Hold The Applause! to the media, its activist network, and selected Du Pont shareholders. A few weeks after the report was released at the National Press Club, Friends of the Earth sent the report to 17 major Du Pont institutional shareholders on September 6, 1991 – among them, major pension funds, several universities, and the Ford Foundation, urging them to back the report’s recommendations. At the time, these shareholders accounted for more than 190 million shares of Du Pont stock, or about 28 percent. Around this date as well, Friends of the Earth send another mailing on the availability of the report to its network of citizen activists, urging them to write to Congress and the Federal Trade Commission to investigate Du Pont’s advertising and environmental claims.

“Du Pont’s Ozone Hole?”

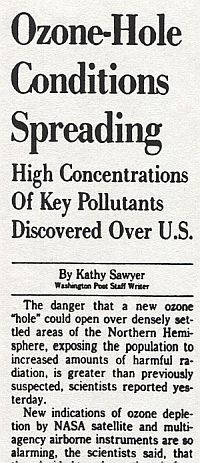

Front-page Washington Post ozone story, Feb 4, 1992.

The header on the FOE press release read: “Du Pont’s Ozone Hole? One Company’s Tactics in Prolonging Global Ozone Depletion.” On the ozone issue, in fact, the Friends of the Earth report, offered a pretty solid timeline and overview of Du Pont’s CFCs business history and its political maneuvering during the ozone policy debates from 1974 through 1991. A bit of that history follows here.

Du Pont began marketing CFCs in 1931 under the trade name Freon, and it soon became the world leader in fluorocarbon chemistry, producing hundreds of compounds used in aerosol spray canisters, insulating foams, solvent cleaning agents, industrial and commercial chillers, and automobile air conditioners. For more than 40 years, Du Pont enjoyed a near monopoly position on many CFC lines, accounting for half of the U.S. CFC market and, at times, more than a fourth of the global market.

All that began to change in 1974, after scientists first theorized that the chlorine in CFCs was destroying the ozone. Du Pont would soon tell Congress it would study the problem, but stated there was no evidence of an ozone hazard, and pledged to stop CFC production if evidence was found. During the regulatory and scientific debates that followed, Du Pont played a prominent role, routinely challenging scientific findings, arguing for “further study,” and orchestrating a political base to forestall regulation.

Du Pont’s “Freon-12” refrigerant (1980s), also known as “R-12” or”CFC-12”.

In 1979, when the National Academy of Sciences reported that continued use of CFCs would lead to 16.5 per cent ozone loss, Du Pont’s reaction was that “no ozone depletion has ever been detected” and that “all ozone depletion figures to date are based on a series of uncertain projections.”

In April 1980 EPA announced its intention to freeze U.S. CFC production at 1979 levels. Du Pont then, by the summer of 1980, used its business base of hundreds of small companies that purchased Du Pont fluorocarbons, to help form the Alliance for Responsible CFC Policy, a lobby that became an effective force against CFC regulation. Du Pont also began to push for an “international scientific consensus” on CFC regulation as a way to buy time and slow any new regulation.

In any case, by 1981, with the Reagan administration now in Washington, any unilateral U.S. regulatory action on CFCs was slowed to a crawl. And while Du Pont had previously begun research on CFC alternatives as a hedge against changing markets, after Reagan was elected, Du Pont’s alternatives research in the 1981-1985 nearly vanished completely. CFC markets, meanwhile – for refrigerants, cleaning agents, and foam insulation – continued to grow globally through the mid-1980s, helping to offset declines that had come with the 1978 aerosol ban.

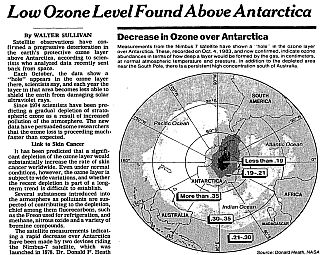

New York Times of November 7, 1985, first to use term “ozone hole” in reporting to describe Antarctica ozone damage..

These findings began to appear in the popular press, with first mention of an “ozone hole” appearing in a New York Times report of November 7th, 1985, accompanied by a black-and-white NASA image with data showing the losses.

Beyond the New York Times, later TV news broadcasts using the color version of the NASA data depicting the “ozone hole,” were seen by millions, bringing the issue fully into the mainstream. The argument that evidence was lacking could no longer stand.

Still, Du Pont in 1985 expanded its CFC production in Japan to reduce costs of exports from the U.S. The following year, EPA Administrator Lee Thomas stated that “empirical verification” of depletion was not a precondition for action to protect ozone. In 1986 Du Pont said it would support limits on CFC growth with global regulation and also resumed its research on CFC substitutes.

In May 1987, Du Pont told the U.S. Senate: “we believe that there is no imminent crisis that demands unilateral regulation,” though previously saying that any regulatory action on CFCs had to be international. At this date, 11 Du Pont plants were producing CFCs. By late 1987, as the international community began negotiations on what would become the Montreal Protocol to regulate CFCs, some Du Pont officials were saying: “We now see the ozone-CFC regulatory situation as a marketing opportunity for substitutes.”

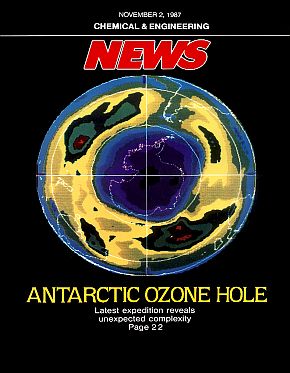

Magazine covers of NASA data & global image showing Antarctica “ozone hole” helped advance popular understanding and concern for protecting the ozone layer. 2 Nov 1987. |

Time magazine cover story of October 1987 -- “The Heat is On” -- featuring both the changing global climate and then worsening ozone depletion problem. |

Du Pont would support the Montreal Protocol, which called for global CFC production to be cut in half by mid-1999. But then, in March 1988– prompted in part by new scientific revelations that ozone depletion was worse than formerly believed, and coupled with a testy exchange of letters between Du Pont and three U.S. Senators that had received press attention — Du Pont stunned competitors and the environmental community by announcing it would stop producing CFCs. The announcement made front-page headlines and brought praise from all quarters.

But what was not generally known when Du Pont made its much-praised phaseout announcement, was that the company’s CFC business had been in decline, and was not producing the profits it once did. Shortly after it made its CFC phaseout announcement, Du Pont began moving quickly to develop and market CFC substitutes with emphasis on HCFCs and HFCs. And by September 1988 or so, Du Pont had filed for U.S. and other patents on many of its HCFC and HFC product lines.

By August 1990, Sharon Roan’s widely praised book, “Ozone Crisis: The 15-Year Evolution of a Sudden Global Emergency,” was published, and included an excellent timeline of events which also structured her narrative. Click for copy.

Du Pont was cited in the New York Times in January 1990 advocating the use of HCFCs and HFCs “until sometime between 2030 and 2050.” But other scientific and environmental interests, including Friends of the Earth and the Natural Resources Defense Council, had begun agitating for restrictions on the substitutes. Proposals for regulating and phasing out HCFCs were then put before both the U.S. Congress and the parties to the Montreal Protocol, but limitations would not take hold for years. For the time being, at least, Du Pont had essentially outflanked the opposition on regulating the new CFC substitutes by way of its own multi-million dollar production plant commitments to produce those substitutes plus major buyer contracts to purchase them.

The Montreal Protocol had actually worked to Du Pont’s advantage. First, it gave a boost to the declining CFC business by imposing production limits that pushed up prices for Du Pont’s and other CFCs. Second, the Protocol specifically approved the substitute HCFCs and HFCs that Du Pont had developed, giving them – at least initially – both environmental acceptability and a guaranteed market.

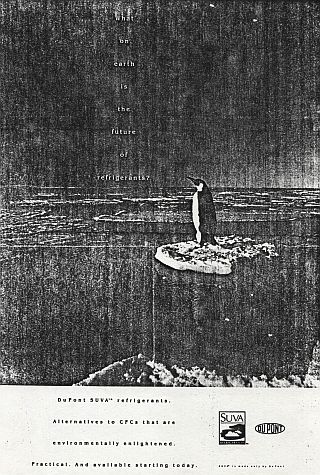

In the end, Du Pont’s dominant market position, its political activity, and its quick capitalization of the CFC substitutes kept it one step ahead of the regulatory process and well on top of the market. It had masterfully played the regulatory and public relations arenas, while simultaneously securing business support and contractual commitments to solidify its market position with the new HCFCs and HFCs. By early 1991, it would begin marketing some of its new CFC substitutes under the Suva trade name.

|

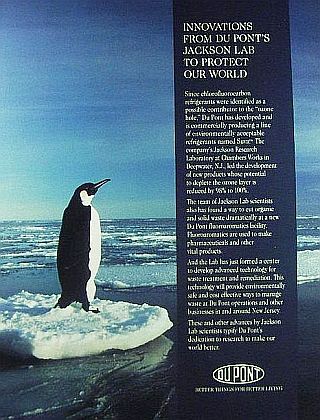

“The Penguin Ad”  Rough copy of January 22, 1991 full-page Du Pont ad in the Wall Street Journal touting its Suva refrigerants. On January 22, 1991, Du Pont began running a full-page advertisement in the Wall Street Journal and other publications featuring a lone penguin standing on a floating block of ice, looking a bit forlorn and peering off toward the open sky (rough copy at right). A brief tagline in the center of the ad, running vertically down the page asks the question: “What on earth is the future of refrigerants?” The answer, “Du Pont’s Suva refrigerants,” the company explains at the bottom of the ad. “Alternatives to CFCs that are environmentally enlightened. Practical. And available starting today.” The day before the ad appeared, on January 21st, at the Grand Hyatt Hotel in New York City, Du Pont’s Vice Chairman, E. P. Blanchard kicked off Du Pont’s the new line of commercially available refrigerants at a press conference, calling them “the fist commercially available family of environmentally acceptable refrigerants.” A similar 1991 print ad also mentioning the new Suva refrigerants would also use the penguin on the floating ice block, but this ad was used to tout the company’s research lab in New Jersey using the headline: “Innovations From Du Pont’s Jackson Lab to Protect Our World.” The message in that ad included the following:  A 1991 Du Pont magazine ad touting Suva refrigerants and environmental advances at Du Pont’s Jackson Labs. “The team of Jackson Lab scientists also has found a way to cut organic and solid waste dramatically at a new Du Pont flouromatics facility. Flouromatics are used to make pharmaceutical and other vital products. “And the lab has just formed a center to develop advanced technology for waste treatment and remediation. This technology will provide environmentally safe and cost effective ways to manage waste at Du Pont operations and others businesses in and around New Jersey. These and other advances by Jackson Lab scientists typify Du Pont’s dedication to research to make our wold better. / Du Pont. Better Things For Better Living.” In its description, and at its August 1991 New York City press conference, Du Pont used the phrase “environmentally acceptable refrigerants” to describe it new line of CFC replacements, not “environmentally safe.” The black and white penguin, meanwhile, would also appear on individual Suva products such as cans and canisters of the chemical, related product items, and promotional paraphernalia. |

Hold The Applause!, meanwhile, offered a snapshot of Du Pont in the early 1990s, and some of the problems and changes it was then experiencing, as well as the company’s proposed leadership philosophy (i.e. “corporate environmentalism”) and attempts to change the way it dealt with pollution and toxic waste. By 1999, Du Pont would sell off Conoco and exit the oil business, and no longer had to concern itself with oil tankers at sea. But it would be Du Pont’s chemistry that continued to haunt the company, as its odyssey with CFCs and ozone had shown in the mid-1970s-early 1990s.

In recent years, however, Du Pont has confronted another chemical legacy with environmental and public health liabilities so large they may be litigated for decades to come. That tale deserves some brief mention next.

1960s ad for “Happy Pan,” a cast iron skillet sealed with Du Pont’s Teflon (polytetrafluoroethylene).

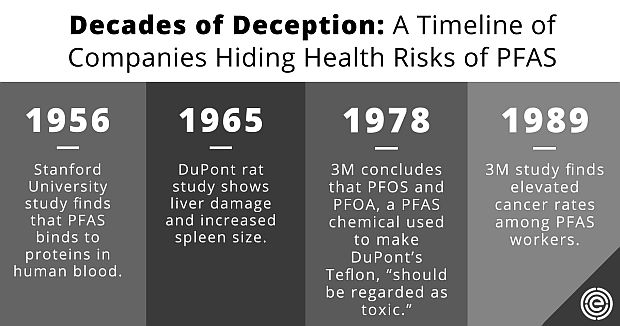

Since the 1950s, Du Pont has been involved with a group of chemicals known in various shorthand forms and chemical abbreviations as: PFOA, PFAS, PFOS, and C-8. PFOA – perfluorooctanoic acid – is one of many synthetic organofluorine compounds collectively known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). These chemicals have been used in industrial quantities since the 1940s to make a wide array of products and treatments. PFAS chemicals are found in consumer and household products, such as non-stick cookware, stain resistant furniture and carpets, wrinkle free and water repellant clothing, cosmetics, lubricants, paint, pizza boxes, popcorn bags, and many other products. PFAS chemicals are now ubiquitous in the environment, have been found in the blood of humans and wildlife everywhere, and with certain exposures, can pose serious health threats.

And it turns out, Du Pont in particular, for decades, withheld information about the chemicals’ health dangers to workers, nearby plant communities, and public health. An abbreviated timeline of some of the events surrounding the Du Pont PFAS saga follows.

In 1938, a DuPont scientist in New Jersey had accidentally discovered polytetrafluoroethylene, a PFAS chemical later named Teflon.

In 1947, the 3-M Company – formerly known as Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing — began producing PFOA for its Scotchguard product.

Map of the Mid-Ohio River Valley area, showing location of Du Pont's Washington Works plant near Parkersburg, WV. Source: WCBE 90.5 FM, Columbus, OH.

In 1951, DuPont began purchasing PFOA from 3M for use in the manufacturing of Teflon at its Washington Works plant. DuPont internally referred to PFOA as C-8.

In the early 1990s, Wilbur Tennant, a cattle farmer near Parkersburg, West Virginia, began recording ill effects in his cows, many dying and with gruesome effects on various internal organs. Tennant suspected the cause was related to an adjacent 66-acre Du Pont landfill, opened in the 1980s, where Du Pont PFOA factory wastes were dumped, infiltrating a local stream that flowed through Tennants’ farm and suspected of poisoning his cattle.

In 1998, Tennant brought his complaint to lawyer Robert Bilott, in Cincinnati, Ohio, who by the fall of 2000, won a court order forcing Du Pont to share all documents related to PFOA. This included some 110,000 pages of internal Du Pont documents, the contents of which soon stunned Bilott. What he found was an incredible story of confidential studies and reports by Du Pont scientists over decades, indicating chemical dangers, but never publicly revealed. It was largely through these findings that a decades-long series of court battles and regulatory change began, continuing to this day, exposing the toxic effects of PFAS chemicals. (See, for example: Nathaniel Rich, “The Lawyer Who Became DuPont’s Worst Nightmare,” New York Times Magazine, January 6, 2016).

Attorney Rob Bilott, in later 2016 New York Times Magazine story about his Du Pont investigation -- shown here on land owned by his client, Wilbur Tennant near Parkersburg, WV. Photo, Bryan Schutmaat for The New York Times. Click for story.

As later noted by the Environmental Working Group (EWG) of Washington D.C. (after Du Pont and 3-M data began to surface in news reports and litigation):

“As far back as 1950, studies conducted by 3M showed that the family of toxic fluorinated chemicals now known as PFAS could build up in our blood. By the 1960s, animal studies conducted by 3M and DuPont revealed that PFAS chemicals could pose health risks. But the companies kept the studies secret from their employees and the public for decades.”

Source: Sample table from the research and reporting of the Environmental Working Group, Washington, D.C.

(See for example, a 1950-2000 timeline complied by EWG of scientific findings with links to dozens of the actual internal memos, studies, and reports that document the various ill-effects and health dangers of PFAS chemicals discovered by 3M and Du Pont scientists, but withheld from regulators, workers, and the public).

Attorney Rob Bilott.

The Du Pont information Bilott had assembled on PFOA led to a further class action he filed in 2001 on behalf of 80,000 people living in areas whereby PFOA had leaked into the water supply. This suit would be settled later.

In 2002, because of an EPA-encouraged 3M phaseout of PFOA, DuPont built its own plant in Fayetteville, North Carolina to continue to produce the chemical, which Du Pont called C-8.

Between 2000 and 2003, various newspaper reporters from the New York Times, The Marietta Times and Columbus Dispatch in Ohio, Charleston Gazette in West Virginia – all played key roles in advancing and uncovering various parts of the early PFAS story, as did other subsequent reporting at the Washington Post, USA Today, ABC News, The News-Journal of Wilmington, DE, and the Environmental Working Group in Washington, D.C.

A sampling of news headlines on Du Pont's Teflon troubles from the 2003-2009 period compiled by the Environmental Working Group (EWG) of Washington, D,C.

In 2004, back in Parkersburg, WV, it was revealed that between 1951 and 2003, more than 1.7 million pounds of C-8 had been “dumped, poured and released” into the environment from Du Pont’s Washington Works plant.

In 2005, the earlier 2001 class action suit brought by Bilott was settled, with Du Pont agreeing to provide up to $235 million for medical monitoring for over 70,000 people living in six water districts around the Du Pont plant in Parkersburg.

In 2005 the EPA fined Du Pont a record $16.5 million over its decades-long cover-up of the health hazards of C8, also known as PFOA.

Callie Lyons’ 2007 book on “the hidden dangers of C-8”, one of the first on the PFAS issue. Click for copy.

In March 2007, Ohio reporter, Callie Lyons, published the first book on PFAS chemicals, Stain-Resistant, Nonstick, Waterproof, and Lethal: The Hidden Dangers of C-8.

In 2009, Du Pont began making Teflon with a new chemical, called GenX.

By 2014, EPA had described the chemicals as “emergent contaminants,” noting:

“PFOA and PFOS are extremely persistent in the environment and resistant to typical environmental degradation processes. [They] are widely distributed across the higher trophic levels and are found in soil, air and groundwater at sites across the United States. The toxicity, mobility and bioaccumulation potential of PFOS and PFOA pose potential adverse effects for the environment and human health.”

In July 2015, DuPont began spinning off major parts of it business into a new publicly traded company named Chemours Company. Chemours would assume major parts of Du Pont’s operations in three segments: Titanium Technologies (titanium dioxide); Fluoroproducts (refrigerants and industrial fluoropolymer resins and derivatives including Freon, Teflon, Viton, Nafion, ECCtreme ECA and Krytox); and Chemical Solutions (cyanide, sulfuric acid, aniline, methylamines, and reactive metals). Chemours also became responsible for the cleanup of 171 former Du Pont waste sites, and would also assume various liabilities arising from DuPont lawsuits. Litigation between Du Pont and Chemours would ensue over these liabilities until a later agreement was reached on sharing liability and judgment costs.

In February 2017, the earlier 2001 class-action suit that Rob Bilott had filed against Du Pont on behalf of the Parkersburg area residents, resulted in Du Pont agreeing to pay $671 million to settle about 3,550 personal injury claims involving a leak of PFOA used to make Teflon at the Washington Works plant. Du Pont denied any wrongdoing.

In March 2017, an investigative documentary about Du Pont and PFOA titled, “The Devil We Know: The Chemistry of a Cover Up,” began airing on American TV. Click for video or DVD.

In November 2018, an EPA draft assessment reported that “animal studies showing effects on the kidneys, liver, immune system and more from GenX,” a chemical initially developed by Du Pont in 2009 as a replacement for PFOA/C-8, but later shown to cause many of the same health problems.

GenX had been used – first by Du Pont and then the Chemours spin-off – at the Fayetteville, North Carolina plant.

In 2012, EPA first announced the discovery of GenX in North Carolina’s Cape Fear river, and by 2014, had discovered 11 additional PFAS substances in the river. Two years later, GenX and other PFASs were found in Wilmington, NC-area drinking water sourced from the Cape Fear river.

In September 2017, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality ordered Chemours to halt discharges of all fluorinated compounds into the river. Since then, other litigation over the chemical in North Carolina and beyond, involving both Chemours and Du Pont, has ensued.

In May 2019, the state of New Hampshire filed a lawsuit against Du Pont, 3M, and other companies, for their roles in the crisis over PFAS-related drinking water contamination in the U. S. resulting from the manufacture and use of more than 4,000 perfluorinated chemicals.

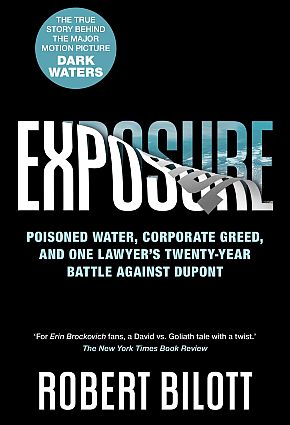

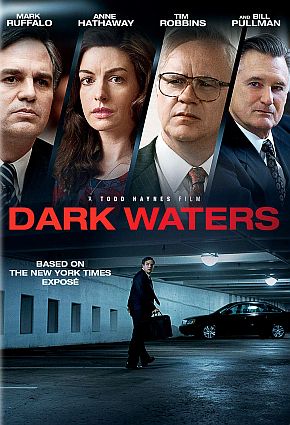

In October 2019, a book written by attorney Robert Bilott, titled, Exposure: Poisoned Water, Corporate Greed, and One Lawyer’s Twenty-Year Battle against DuPont, appeared. A month later, Dark Waters, a November 2019 Hollywood was released based on attorney Rob Bilott’s litigation with Du Pont and the profile of him that had appeared in New York Times Magazine.

In March 2021, EPA announced that it would develop national drinking water standards for PFOA and PFOS. Later that month, EPA also announced plans to revise wastewater standards (effluent guidelines) for manufacturers of PFAS chemicals.

In July 2021, Maine became the first U.S. state to ban PFAS compounds in all products by 2030, except for instances deemed “currently unavoidable.” And since then, at least 10 states — and numerous local jurisdictions — have brought PFAS-related lawsuits against Du Pont, 3-M, Chemours and other companies. Recently, for example, on May 25th, 2023, Rhode Island’s Attorney General, Peter Neronha, filed a lawsuit against a list of PFAS manufacturers – including 3M and Du Pont – charging they have caused significant harm to the state’s residents and natural resources. Neronha faulted the companies for engaging in what he described as “a massive and widespread campaign to knowingly deceive the public,” moving assets to avoid paying for damages, and manufacturing, marketing and selling hazardous chemicals for decades while knowing the risks.

On June 2, 2023, Chemours, DuPont and Corteva (another Du Pont spin-off), in a legal settlement, announced an agreement in principle to set up a $1.19 billion fund to help remove toxic PFAS chemicals from public drinking water systems. The deal, the result of a consolidation of cases before a federal Judge in Charleston, S.C., still requires judicial approval, but would resolve a number of lawsuits involving water systems that already had detectable levels of PFAS contamination, as well as those required by EPA to monitor for PFAS contamination. As many as 200 million Americans are currently believed to be exposed to PFAS in their tap water. And PFAS-related litigation has already involved more than 4,000 cases filed in federal courts across the country, with more on the way. Du Pont and its spin-offs, it appears, will be dealing with the PFAS saga for some time to come.

In 1935, Du Pont adopted the slogan, “Better Things for Better Living...Through Chemistry,” dropping “through chemistry” in 1982 -- adopting a new slogan in 1999, “The Miracles of Science”.

Additional stories at this website on business and the environment can be found at the Environmental History topics page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing, and continued publication of this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

_______________________________________

Date Posted: 7 June 2023

Last Update: 17 June 2023

Comments to:jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/PopHistoryDig

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Applause For Du Pont? An Environmental

Critique,”PopHistoryDig.com, June 7, 2023.

_______________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“Applause” (Du Pont TV ad), Hagley Digital Archives, Hagley.org, Date Created, October 1, 1990.

“DuPont Conoco Double-Hulled Oil Tankers Seal Clapping Commercial (1991), YouTube .com, posted by RetroCommercial.com, 2011.

Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborn, Inc. (BBDO), “Applause,” Commercial No. DDCA 0063, Client: Du Pont Corp., BBDO storyboard, 1990.

Charles Alexander, “History’s Biggest Merger: Du Pont-Conoco; Du Pont Springs a Surprise $7 Billion Offer for Resource-Rich Conoco,” Time, July 20, 1981.

Thomas L. Friedman, “Du Pont Victor in Costly Battle to Buy Conoco,” New York Times, August 6, 1981, p. 1.

Display Ad 73: “The Ozone Layer Vs. The Aerosol Industry. Du Pont Wants to See Them Both Survive,” New York Times, June 30, 1975, p. 30.

“You Want The Ozone Question Answered One Way or The Other. So Does Du Pont,” Du Pont’s 1975 two-page newspaper advertisement, Science, Vol. 190, No.4209, October 1975, p. 8. (also appeared in the Washington Post, September 30, 1975, p. A-10.)

Walter Sullivan, “Low Ozone Level Found Above Antarctica,” New York Times, November 7, 1985, p. B-21.

Paul Brodeur, “Annals of Chemistry: In The Face of Doubt,” The New Yorker, July 9, 1986.

William Glaberson, “Behind Du Pont’s Shift On Loss of Ozone Layer,” New York Times, March 26, 1988.

Cynthia Pollock Shea, “Business Forum: The Chlorofluorocarbon Dispute; Why Du Pont Gave Up $600 Million,” New York Times, April 10, 1988, p, A-2.

David A. Hounshell and John Kenly Smith, Jr., Science and Corporate Strategy: Du Pont R&D, 1902-1980, Cambridge University Press, 1988. Available at Amazon.com.

Forest Rheinhardt, “Du Pont Freon Products Division (A)”, Case 8-389-111, Harvard University, Harvard Business School Case Study, January 1989.

“Remarks of E. S. Woolard, Jr., Chairman, Du Pont, Before the American Chamber of Commerce,” (UK), London, May 4, 1989.

Barnaby J. Feder, “Who Will Subscribe to the Valdez Principles?,” New York Times, September 10, 1989, Section 3, p. 6.

Edgar S. Woolard, “Remarks At the World Resources Institute,” Washington, D.C., December 12, 1989.

Matthew L. Wald, “A Split on the Value of 2-Hull Tankers,” New York Times, May 15, 1989, p. A-16.

Tom Horton, “The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill: Paradise Lost,” Rolling Stone, December 14, 1989.

Sharon L. Rowan, Ozone Crisis: The 15 Year Evolution of A Sudden Global Emergency, John Wiley & Sons, 1989. Available at Amazon.com.

David Kirkpatrick and Alicia Hills Moore, “Environmentalism: The New Crusade. It May Be the Biggest Business Issue of the 1990s. Here’s How Some Smart Companies Are Tackling It,” Fortune Magazine, February 12, 1990.

Jack Doyle, “Business As Usual” (Ed: 1989 Was A Banner Year for Environmental Crime, But Tougher Punishments May Be on The Way…), Not Man Apart, Friends of the Earth, Vol. 19, No.5/6, Dec 1989-Jan 1990, p. 12.

John Holusha, “Breaking Oil Industry Ranks, Conoco Buys 2-Hulled Ships,” New York Times, April 11, 1990, p. 1.

“Oil Company To Buy Tankers With Double Hulls — Conoco Has Two On Order Now; Sen. Adams Lauds `Good Citizen’,” Seattle Times, April 11, 1990.

Jack Doyle, “`Enviro-Imaging’ for Market Share: Corporations Take to the Ad Pages to Brush Up Their Images,” Not Man Apart, Friends of the Earth, Vol. 20, No. 2, April-May 1990, pp. 10-11.

Malcolm W. Browne, “Grappling With the Cost Of Saving Earth’s Ozone,” New York Times, July 17, 1990, p. C-1.

Remarks of E.S. Woolard, Jr., Chairman, Du Pont, Before the Society of the Chemical Industry, Monte Carlo, October 8, 1990.

Elizabeth Cook, “Global Environmental Advocacy: Citizen Activism in Protecting the Ozone Layer,” Ambio, Vol. 19, No. 6-7, October 1990, pp. 334-338.

John Holusha, “Ed Woolard Walks Du Pont’s Tightrope,” New York Times, October 14, 1990, Sunday Business, p.1.

Remarks by E.S. Woolard, Jr., Chairman, Du Pont, At the Detroit Economic Club, Detroit, Michigan, November 19, 1990.

Michael J. Sniffen, “Environmentalists Lost Du Pont Ozone Lawsuit,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 5, 1991, p. B-12.

Jack Doyle, “One Way For Business To Go Green” (Valdez Principles), New York Times, Sunday Business, March 10, 1991.

News Release, Friends of the Earth, Washing-ton, DC, “Friends of the Earth Challenges Du Pont on Ozone Policy,” April 5, 1991, Contact Liz Cook, Jack Doyle.

David Rotman, “Growing Ozone Damage Adds to CFC Worries,” Chemical Week, April 17, 1991, p. 9.

News Release, Friends of the Earth, Washing-ton, DC, Press Conference before Du Pont Shareholders Meeting, Wilmington, DE, April 24, 1991, “Friends of the Earth Calls Du Pont’s Ozone Policy Dangerous,” Remarks by Liz Cook, Ozone Campaign Director, Friends of the Earth.

Michael S, Clark, President, Friends of the Earth, Letter to William K. Reilly, Administrator, U.S Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C., April 24, 1991, 2pp (ozone policy).

Bob Bauers, “Du Pont Co.’s Annual Meeting Becomes Environmental Forum,” The News-Journal (Wilmington, DE), April 25, 1991, p. 1.

Liz Cook, “CFC Substitute Turns Out To Do More Harm,” Atmosphere, A Publication of Friends of Earth International, Ozone and Climate Protection, Washington, D.C., Vol. III, No.4, June 1991, p. 6.

“To Corporate Leaders: ‘We Will Be Watching’,” Statement of Brent Blackwelder, Acting President, Friends of the Earth, National Press Club, Washington, D.C., August 27, 1991 (release of Friends of the Earth report, Hold The Applause!), 2 pp.

“Better Things and Better Living: Challenging Du Pont Science,” Statement of Jack Doyle, Senior Analyst, Technology & Corporate Policy, Friends of the Earth, National Press Club, Washington, D.C., August 27, 1991 (release of Friends of the Earth report, Hold The Applause!), 2pp.

Jack Doyle, Hold The Applause! A Case Study of Corporate Environmentalism as Practiced at Du Pont, Friends of the Earth, Washington, D.C., 112pp, August 1991.

Reuter’s, “Environmental Group Calls Du Pont’s Ads Deceptive,” Washington Post, August 28, 1991, p. F-3.

Donna Shaw, “Environmentalists: Du Pont’s Claims Don’t Hold Water,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 28, 1991, p. C-1.

Molly Murray, “A Group Protests: Report Blasts Du Pont as ‘Telfon Polluter’; Group Says Firm Is Not An Environmental Leader,” The News-Journal (Wilmington, DE), August 28, 1991.

Karen Riley, “Environmental Group Points to Du Pont as Major Polluter,” Washington Times, August 28, 1991, p. C-10.

“Environmental Group Raps Du Pont,” Los Angles Times, August 28, 1991.

“In Passing: Did They Ask The Dolphins?,” Editorial, Philadelphia Inquirer, August 30, 1991, p. 18-A

“The New Accounting: What’s Next After Du Pont at FOE,” National Environment Digest, Washington, D.C., September 2, 1991.

“Environmental Group Accuses Du Pont of Being Nation’s Largest Polluter, Calls Company’s Environmental Advertising Campaign Deceptive,” Corporate Crime Reporter, Vol 5, No. 39, September 2, 1991.

Ronald Begley, “Muted Applause for Du Pont,” Chemical Week, September 4, 1991, p. 22.

Edward Flattau, Columnist, “Du Pont Draws Wrath of Greens, Press,” The New Mexican, Sunday, September 8, 1991.

“Advertising Under Attack” and “Policing ‘Green’ Ads,” CQ Researcher – Congressional Quarterly, Washington, D.C., September 13, 1991.

Bob Garfield, “Ad Hype Yielding to Substance,” and Catherine A. Dold, “Hold Down The Noise,” Advertising Age, October 28, 1991.

Martha M. Hamilton, “Conoco Quits Oil Project in Rain Forest,” Washington Post, October 12, 1991, p. C-1.

Peter Montague, Ph.D., “How to Civilize Corporate Behavior,” Rachel’s Hazardous Waste News, No. 259, November 13, 1991.

Jack Doyle, “‘Green Ads’ Need New Ethics Code,” Op-Ed, San Francisco Chronicle, November 23, 1991.

Rajib N. Sanyal and Joao S. Neves, “The Valdez Principles: Implications for Corporate Social Responsibility,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 10, No. 12 (Dec., 1991), pp. 883-890

John Holusha, “Environmentalists Assess Corporate Pollution Records,” New York Times, December 9, 1991, p. D-1.

Jack Doyle, “Audits Are Their Own Reward,” The Environmental Forum, The Policy Journal of the Environmental Law Institute, Washington, D.C., Vol. 9, No.7, Jan/Feb 1992, pp. 38-39.

Kathy Sawyer, “Ozone Hole Conditions Spreading; High Concentrations of Key Pollutants Discovered Over U.S.,” Washington Post, February 4, 1992, p. 1.

Michael Weisskopf, “U.S. May Seek To Hasten Action to Protect Ozone; Sings of Atmospheric Damage Alarm Officials, “ Washington Post, Feb 6, 1992, p. A-3.

Press Release, “Du Pont’s Ozone Hole? One Company’s Tactics in Prolonging Global Ozone Depletion” (re: Hold The Applause! report) Friends of the Earth, Washington, DC, February 6, 1992, 2pp. Contact: Carla Gaffney.

“America’s Corporate Record Holder – For Toxic Pollution,” People, April 27, 1992, p. 54.

Jack Doyle, Friends of the Earth, Washington, D.C., Letter to Edgar S. Woolard, Jr., Chairman and CEO, Du Pont, Wilmington DE, April 28, 1992 (with enclosures)..

Statement of Jack Doyle, Senior Analyst, Technology & Corporate Policy, Friends of the Earth, Annual Meeting of Shareholders, E.I. du Pont Nemours & Co., Hotel Du Pont, Wilmington DE, Arril 29, 1992, 8pp.

Bruce W. Karrh, V.P., Safety, Health & Environmental Affairs, Du Pont, Wilmington, DE, Letter to Jack Doyle, Senior Analyst, Friends of the Earth, Washington , DC, May 12, 1992.

Paula L. Green, “Why More U.S. Firms Clean Up Their Act: To Beat The Competition,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 26, 1992, p. C-9.

Jack Doyle, “Hold The Applause: A Case Study of Corporate Environmentalism,” The Ecologist, Vol. 22, No. 3, May/June 1992, pp. 84-90.

Joseph Weber, “Du Pont’s Trailblazer Wants To Get Out of The Woods; Ed Woolard Has Been Shrinking or Spinning Off Businesses He Once Saw As Engines of Growth,” Business Week, August 31, 1992, pp. 70-71.

Jack Doyle, Friends of the Earth, Telephone Conversation with Jack Malloy, Senior V.P. & Special Counsel to Ed Woolard, Du Pont, September 2, 1992.

Brent Blackwelder, Acting President, Friends of the Earth with Jack Doyle and Liz Cook, Meeting with Du Pont’s CEO Ed Woolard and Jack Malloy, Senior V.P. & Special Counsel to Ed Woolard, at Du Pont Offices, Mills Building, 1701 Pennsylvania Ave, Washington, D.C., September 4, 1992.

Peter Applebome, “Du Pont Settles Growers’ Suits Over Fungicide [Benlate]; Agrees To Pay $4 illion as Jury Deliberates,” New York Times, August 13, 1993, p. A-10.

Carol Kaesuk Yoon, “Thinning Ozone Layer Implicated in Decline Of Frogs and Toads,” New York Times, March 1, 1994, p. C-4.

Larry Levinson, UPI (Trenton, N.J.), “Court Ruling Sets Precedent” (Du Pont & worker asbestos exposure), UPI.com, June 1, 1989.

Bruce Watson, “The Troubling Evolution of Corporate Greenwashing,” TheGuardian.com, August 20, 2016.

Adam Rome, “Du Pont and the Limits of Corporate Environmentalism,” Business History Review, Vol. 93 , Issue 1: Business and the Environment Revisited, Spring 2019, pp. 75-99.

Marina Vassilopoulos, “An In-Depth Look At Greenwashing… And Its Consequences,” UnsustainableMagazine.com, October 22, 2022.

Philip Shabecoff, “Du Pont to Halt Chemicals That Peril Ozone,” New York Times, March 25, 1988, p. 1.

Sarah V. Poor, Alister R. Olson, Michael P. Clough, and Benjamin C. Herman, Spotting Pseudoscience, “Ozone Depletion: Fabricating a Hole in the Scientific Evidence,” Story BehindTheScience.org.

B. Smith, “Ethics of Du Pont’s CFC Strategy 1975–1995,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 17, No. 5, April 1998, pp. 557–568.

R. P. Mullin, “What Can Be Learned from Du Pont and the Freon Ban: a Case Study,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 40, No. 3, 2002, pp. 207-218.

J. Maxwell and F. Briscoe, “There’s Money in The Air: The CFC Ban and Du Pont’s Regulatory Strategy,” Business Strategy and the Environment, 6(5), 1997, pp. 276-286.

Megan Nielson, “Honesty and Integrity in PR – Lessons from Du Pont,” CommuniquePR .com, August 19, 2021.

PFAS-Related

“Perfluorooctanoic Acid,” Wikipedia.org.

“Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances,” Wiki-pedia.org.

“Timeline of Events Related to Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances,” Wikipedia.org.

“Du Pont Hid Teflon Pollution For Decades,” EWG.com (Environmental Working Group, Washington, DC), December 13, 2002.

“Robert Bilott,” Wikipedia.org.

Callie Lyons, “Examining the Water We Drink: Concerns About C8 Linger,” The Marietta Times, (Ohio), September 27, 2003.

Sharon Lerner, “The Teflon Toxin: Du Pont and the Chemistry of Deception,” TheInter-cept.com, August 11, 2015.

Mariah Blake, “Welcome to Beautiful Parkersburg, West Virginia,” HuffingtonPost .com, August 27, 2015.

“GenX,” Wikipedia.org.

Ken Otterbourg, “Teflon’s River of Fear: Chemical Giant Chemours Is Facing off Against Residents of North Carolina in a Battle over a Potentially Harmful Compound Used to Make Nonstick Pans,” Fortune.com, May 24, 2018.

DuPont Lawsuits (re PFOA pollution in USA), Business-HumanRights.org.

Bill Walker, “EWG and Toxic Fluorinated Chemicals: 20 Years in the Fight Against PFAS,” EWG.com, July 24, 2019.

Bill Walker, “Groundbreaking Reporting Helped Bring ‘Dark Waters’ to Light,” EWG.com, December 6, 2019.

Randall Chase, “DuPont, Chemours Reach Pact Over Liability for ‘Forever Chemicals’ PFAs Pollution,” InsuranceJournal.com, January 25, 2021.

David Gelles and Emily Steel, “How Chemical Companies Avoid Paying for Pollution; Du Pont Factories Pumped Dangerous Substances into the Environment. The Company and its Offspring Have Gone to Great Lengths to Dodge Responsibility,” New York Times, October 20, 2021.

Ry Rivard and Jordan Wolman, “‘Forever Chemicals’ Are Everywhere; The Battle Over Who Pays to Clean Them Up Is Just Getting Started…,” Politico.com, September 13, 2022.

Associated Press, “Rhode Island Attorney General Sues Manufacturers of ‘Forever Chemicals’,” PBS.org, May 25, 2023.

Ben Casselman, Ivan Penn and Matthew Goldstein, “Three ‘Forever Chemicals’ Makers Settle Public Water Lawsuits; The $1.19 Billion Agreement, Announced by Chemours, Dupont and Corteva, Wouldn’t Resolve All the Claims Against Them,” New York Times, June 2, 2023.

_____________________________