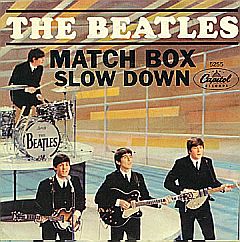

The Beach Boys’ first album, “Surfin’ Safari” of October 1962, had a modest showing on the charts at No. 32. Click for CD.

In America, the Beach Boys would become one of the hottest and most successful groups of the 1960s, credited with inventing “California rock” and “sunshine pop” — and along with the Beatles in the mid-1960s — pushing the envelope on a new and imaginative front of pop music composition. What follows here is a brief history of the Beach Boys’ early career, and in a companion Part 2 story, a more focused look at six of their 1963-1967 songs, with MP3 versions.

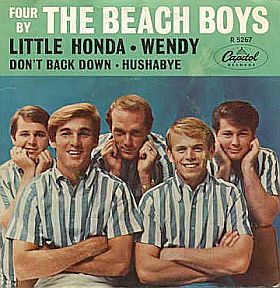

Beach Boys from top left, clockwise: Mike Love, Brian Wilson, Carl Wilson, Dennis Wilson & Al Jardine.

The Beach Boys first started playing together as teenagers while attending Hawthorne High School in Hawthorne, California, a Los Angeles County town not far from Manhattan Beach and the Pacific Ocean. The Wilson boys had been encouraged by their parents to try music and sports during their school years. Brian Wilson, for one, had played varsity baseball at Hawthorne High.

In 1959, after Brian had graduated, he and cousin Mike Love started some singing together, with their group later expanding to include the two other Wilson brothers and friend Al Jardine. At first, they sang at family gatherings and also played locally under various names, Kenny and The Cadets, Carl and Passions, and The Pendletones. But that soon changed as good fortune came their way.

|

The Beach Boys “Surfin’ Safari” |

In December 1961, the first record they made, titled “Surfin,” had success locally, charting on Los Angeles radio station KFWB and later rising to No. 75 on the Billboard national chart. By then they were using “The Beach Boys” as their group name — a name chosen by their first record distributor, Candix.

On December 31, 1961 the Beach Boys appeared on the bill at the Ritchie Valens Memorial Concert in Long Beach, California, one of their earliest public appearances. By June 1962 they had made a demo tape of songs including “Surfin Safari,” Surfer Girl,” and “409” that later convinced Capitol Records’ Nick Venet to sign them to a recording contract. Other musicians and instrumentalists had picked up on the surf scene in the early 1960s before the Beach Boys had. But with the imaginative composing and songwriting of Brian Wilson, coupled with very smooth vocal harmonies and upbeat tempo, the Beach Boys soon became set apart from the rest.

Beach Boy Troubles

The Beach Boys’ rise to fame in the 1960s, however, wasn’t without its difficulties, including trouble on the homefront with their father, Murry, who was also their first manager. Murry, it would be later learned, was physically and verbally abusive toward his sons.

Brian, who became the gifted musician and songwriter for the group, would have his own emotional and behavioral problems, and would descend into alcohol, drugs, and depression just as the group peaked. Other Beach Boys would have their ups and downs as well, and along the way there would be some strife within the group over musical style and direction.

Yet, despite these troubles, the group managed to become one of America’s most popular, successful, and well-liked of the 1960s and beyond, as they would continue performing, in various forms, through the 2000s. But during their peak years of the early- and mid-1960s, they, along with the Beatles, became a dominant group on the pop charts and, also like the Beatles, an influential force in music making and popular culture.

According to Billboard, in terms of single and album sales, the Beach Boys are among the top-selling American bands of all time. Worldwide they have sold an estimated 100 million records (an estimate likely on the low side). Between 1961 and 1988, they turned out thirty-six Top 40 hits, more than any other U.S. rock band. They also produced 56 songs that charted in the Top 100. Four of their songs were No. 1 hit singles. Rolling Stone placed the Beach Boys at No.12 on the magazine’s 2004 listing of “The 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.” New compilations of Beach Boys’ music have appeared as recently as 2009. Currently on Amazon.com there are more than 100 offerings of various Beach Boys’ recordings.

Surf, Cars & Girls

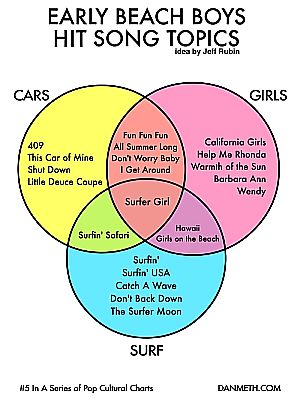

In the early 1960s, the Beach Boys hit upon a kind of magical if basic formula: turning out songs in three sure-fire, teen-appealing areas – cars, girls and surfing. The graphic below illustrates these three thematic areas, showing where particular Beach Boys’ songs landed in the 3-topic schema, some falling in two or more areas.

As this illustration shows, the Beach Boys hit upon a productive formula of 1960s’ song-making that fell into three basic teen-appealing areas: cars, girls, and surf.

The Beach Boys were teenagers themselves when they first started, and they fashioned their material from their own experiences with high school, cars, and teenage romance. And these were also the experiences of tens of millions of Baby Boomers — 78 million strong; all coming of age at the time. The Boomers would “grow up” with the Beach Boys’ music, become their primary audience and market in the 1960s and for decades thereafter. The Boomers, in fact, would prove to be reliable “repeat buyers” of Beach Boys’ music over the next 40 years as it was repackaged into tape, CD, and MP3 forms and also numerous compilation albums.

Although the only surfer among the Beach Boys was Dennis Wilson, who had first suggested they try some songs about surfing, they managed to successfully use that motif as part of their early group image. But what really distinguished the Beach Boys’ music was their distinctive sound, their gorgeous harmonies, and quite often, the creative vocal arrangements and instrumentation in their songs.

Brian Wilson, in particular, would become the creative force behind much of the group’s music, serving as songwriter, arranger, and producer. Brian also co-wrote songs with Mike Love and others and initially shared lead singing duties during the first few years.

“Surfin’ USA” album, with its title track, was the big Beach Boys breakout in 1963, selling more than a million copies, hitting No. 2 on the ‘Billboard’ albums chart. Click for CD.

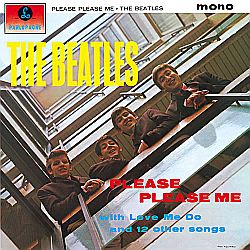

Along with these early singles were several albums. Surfin’ Safari came in October 1962 and had a modest showing at No. 32. Surfin’ USA came next in March 1963, and along with the single of that name, was something of a breakout for the group, with both single and album rising to No. 2 on the U. S. Billboard charts. Surfin USA even outsold a number of the group’s singles at the time, which were then typically the more popular product. Surfin USA remained on the Billboard album chart for 78 weeks.

Brian Wilson’s songwriting and vocal arrangements were found throughout this album, helped along with double tracking technology in the studio. The song credits for the title track, “Surfin USA,” are shared by Brian Wilson and Chuck Berry since the basic tune, though not the lyrics, was based on Berry’s 1958 hit, “Sweet Little Sixteen.” This album also includes five Beach Boys instrumentals.

Beach Boys shown in early 1960s photo with famous Capitol Records building in Hollywood behind them. They were the first rock group to sign with Capitol in 1962.

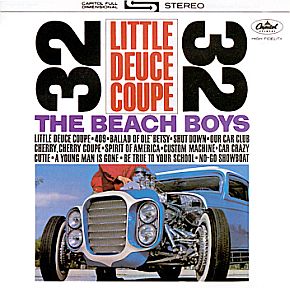

Beach Boys’ Oct 1963 album “Little Deuce Coupe” focused on one of their themes, hot rod cars & car culture – rising to No. 4 on the ‘Billboard’ charts. Click for CD.

To protect their turf in this arena, Brian Wilson then hurried production of the Little Deuce Coupe album as their “hot rod” collection, with a mix of old and new Beach Boys songs. One of their car songs, “409” — which refers to a an especially “hot” engine size of that day — was an earlier modest hit, released on the B-side of “Surfin Safari,” landing at No. 72 on the Billboard 100.

The album Little Deuce Coupe became a No. 4 hit on the Billboard charts and would eventually also sell one million copies. By the end of 1963, three of the Beach Boys’ LPs had risen into the Top Ten and the group was touring regularly.

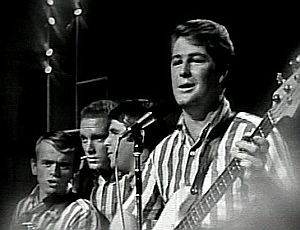

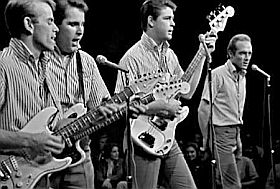

Beach Boys performing at the October 1964 TAMI concert, from left: Al Jardine, Mike Love, Carl Wilson, and Brian Wilson. Not shown Dennis Wilson on drums.

1964-65

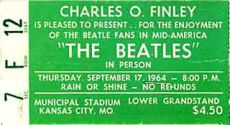

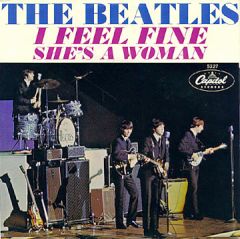

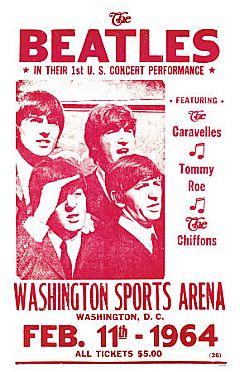

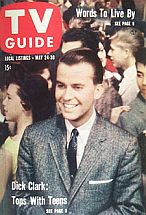

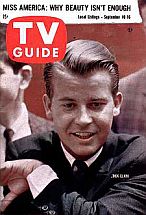

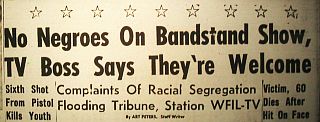

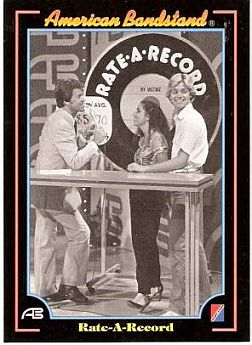

In 1964 came more Beach Boys hits, such as: “Fun, Fun, Fun,” “Don’t Worry, Baby,” When I Grow Up,” and “Dance, Dance, Dance.” The group’s first No. 1 hit, “I Get Around,” came in June 1964. By the end of 1964, two years into their career, the Beach Boys had placed twelve hit songs in the Top 40. They also continued turning out albums. Shut Down Volume 2 came out in March 1964, followed by All Summer Long in July, which rose to No. 4 on the albums chart. On April 18th, 1964, the Beach Boys made their first appearance on the nationally-televised American Bandstand show with Dick Clark. They also began touring outside the U.S. in 1964, traveling to Australia in January and later, Europe and U.K. in September. The “British invasion” of the American pop music charts, led by the Beatles, was well underway by this time. But the Beach Boys abroad on their first tours in 1964 were well received, and their music would soon appear on record charts in those countries and the world over.

|

“Sunshine Pop Mythology” “…California — in 1963, it was the one place west of the Mississippi where everyone wanted to be. Rich and fast, cars, women, one suburban plot for everyone, a sea of happy humanity sandwiched between frosty mountains and toasty beaches, all an easy drive from the freeway. But was it that simple and bright? Behind the pursuit of fun, you might hear a hint of tedium, or a realization that each passing day blemished the pristine Youth this culture coveted. Brian Wilson understood this perfectly and, characteristically, made it attractive and not a little heroic, as in ‘I Get Around,’ in which he expresses sheer frustration: ‘I’m gettin’ bugged drivin’ up and down the same old strip.’ His business was the revitalization of myths he wished were true and knew were false. The hollowness, properly dressed up as adolescent yearning, could itself be marketed in ‘teen feel’ pop songs.” – Jim Miller, “The Beach Boys,” The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock n Roll, 1992, p 194. |

Shows & Albums

Back in the States by late September 1964, the Beach Boys made their first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, performing on September 27th, live versions of “I Get Around” and “Wendy.” In late October 1964, they were one of the featured acts at “The TAMI Show” concert in Santa Monica, California (Teenage Awards Music International). The TAMI Show was a filmed concert event and it included other notable acts such as James Brown, Chuck Berry, the Rolling Stones, and the Supremes.

In November 1964, The Beach Boys Concert album was released, comprised of 13 live music tracks from earlier performances they had given in 1963 and 1964 at the Civic Memorial Auditorium in Sacramento. This album — billed as their first “live” album — rose to No. 1 in the first week of December 1964 and remained there for the rest of the month. It was their first No. 1 album.

Also released by then was The Beach Boys’ Christmas Album with a dozen Christmas songs. The Beach Boys had a previous Top Ten Christmas hit in 1963 with “The Little Saint Nick,” which also appeared on this album. The Beach Boys’ Christmas music would continue to do well in subsequent years.

In any case, by the end of 1964, they had five albums on the pop charts simultaneously.

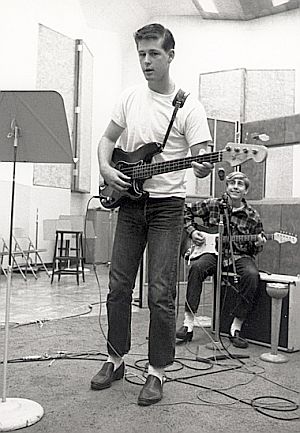

Brian Wilson in studio.

Brian Quits Tour

Brian Wilson, meanwhile, exhausted from his studio work and touring, suffered a nervous breakdown on a trip to Texas in late December. At this point, he decided to quit touring with the band, except for TV appearances, and focus more on the Beach Boys’ studio productions. On the road, meanwhile, there were stand-ins for Brian, including for a time, Glen Campbell and later, Bruce Johnston.

But Brian’s studio work helped yield more Beach Boys hits in 1965. “Do You Wanna Dance” came out in February 1965; “Help Me, Rhonda” was a Beach Boys’ No. 1 hit in April; “California Girls,” which Brian Wilson and Mike Love wrote together, hit No. 3 in July; and “Barbara Ann” rose to No. 2 in December. The Beach Boys by this time had put 16 singles in the Top 40.

Three new albums were produced that year as well: The Beach Boys Today! in March; Summer Days (and Summer Nights!) in June; and Beach Boys’ Party! in November.Of these three, The Beach Boys Today! marked a progression in the group’s music, using more complicated arrangements on some tracks — including strings, horns, piano, keyboards, and more percussion. This album rose to No. 4 and sold more than a million copies.

Summer Days (and Summer Nights!) was also a success, becoming their ninth consecutive gold-certified album, rising to No. 2 on the Billboard albums chart.

Brian Wilson, however, was just warming up, musically. His next venture would be an album that would influence and challenge the Beatles; an album named Pet Sounds. More on this in a moment. First, a little closer look at Brian Wilson.

|

“Brian’s Song”  A very young Brian Wilson, foreground, with equally young David Marks behind him, in the studio, early ‘60s. Home life for Brian and his brothers was difficult, especially with their father, as the boys suffered physical and emotional abuse. Brian, in adolescence, used his music as an escape, playing the piano at times to drown out the bickering and fighting at home. Although he played some sports in high school, he withdrew into music, also used it to avoid social situations. But with music, Brian’s brain was wired for sound, “thinking in three part harmony,” as he once put it. As a boy, he was inspired the first time he heard the Four Freshmen singing on the radio. Their harmony “struck a chord” with Brian which he sought to emulate.  Young Brian Wilson at mic, early 1960s, with Mike Love, in recording studio.  Brian Wilson, 2nd from right, performing with the Beach Boys at unidentified venue, likely in the 1963-65 period. Brian Wilson, however, had his demons, which emerged at a most untimely juncture, precisely during the Beach Boys’ best years. By the mid-1960s he struggled with alcohol and drugs alongside the pressure of turning out the Beach Boys’ music. Early in 1965, he became involved with drugs and also had associated bouts of depression. Still he turned out the hits, some of which were written during, or in the aftermath of, drug experiences. In 1988, the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame called Wilson “one of the few undis- puted geniuses” in pop music. By 1968 he became addicted to cocaine. Years went by with Wilson’s condition undiagnosed, as even friends passed it off as merely “Brian’s odd behavior.” Wilson subsequently went through a period of about 20 years of ups and down with his drug problems, rehabilitations, and periodic lapses. In 1988, after the Beach Boys were inducted into the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame, he began a fuller recovery and also a solo recording career which he has continued though the 2000s. At the Beach Boys’ induction into the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame in 1988, Brian was singled out in the induction notice as “one of the few undisputed geniuses in popular music.” Wilson, added the Hall of Fame notice, “possessed an uncanny gift for harmonic invention and complex vocal and instrumental arrangements.” An offering of some of his creations with the Beach Boys can be heard in the six musical samples that appear in Part II of this article. See also at this website, a review (with trailer) of the 2015 film, Love & Mercy, about Brian Wilson. |

Pet Sounds

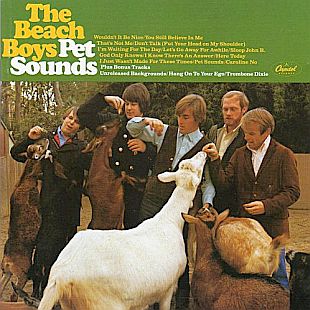

Despite the San Diego Zoo’s animals, “Pet Sounds” refers to Brian Wilson’s favorite or “pet” sounds in the album and also the initials of his studio idol, Phil Spector. Click for CD.

Calling the album a “carefully sculpted and lavishly arranged set of songs,” Moon also lauded Pet Sounds as “a high-water mark of pop craft in general.” He also called it Brian Wilson’s most mature music making. And although the album has the California sunshine of the early Beach Boys, it is now seen “through darker lenses,” as Moon puts it – by people old enough to remember the carefree days, but are now tempered by adult knowledge, real life experience, lost love, and the call of responsibility. Pet Sounds, in a sense, was a Beach Boys graduation of sorts, to a new level of musicality.

Released in May 1966, Pet Sounds included notable singles such as, “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” “God Only Knows,” and “The Sloop John B,” among others. However, U.S. audiences turned up their noses to this album at first, in part because it was not the old sunshine pop that many knew and loved, and in part because many just didn’t get it. In fact, even among the Beach Boys themselves, there were some pretty fierce differences over the making of this album and moving away from their previous formula. Capitol executives, in fact, wanted to shelve the album and only reluctantly agreed to its release, providing little promotion. When it then rose only to No. 10 on the U.S. album charts, Capitol — despite the success of some of its songs like “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” — produced and released a compilation album in July 1966, Best of the Beach Boys. Brian Wilson viewed Capitol’s act as sabotage. Pet Sounds, in fact, had actually done better in the U.K. when it was released there six weeks after the U.S. release, rising to No. 2 and getting rave reviews.

Brian Wilson on the cover of Charles Granata’s 2003 book on the making of “Pet Sounds.” Click for book.

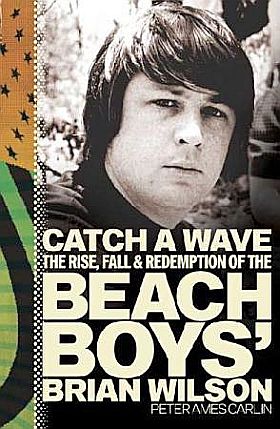

“Certainly Pet Sounds is a melancholy work,” observes Peter Ames Carlin, a music critic who has written on the Beach Boys. “But the beauty of the songs, coupled with the sheer invention of [Brian Wilson’s] production, is rapturous. The album echoes with that distinctly utopian feeling that anything is possible…”

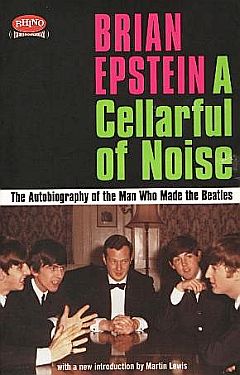

Pet Sounds would be lauded in later years by the critics for its innovative use of folk, blues and jazz blended with those perfect Beach Boy harmonies. But beyond that, Pet Sounds showcased Brian Wilson as studio wizard who, like his idol Phil Spector, became a pioneer of using the studio “as an instrument” (see also at this website, for example, “Be My Baby“). With various studio techniques such as multiple tracking, Wilson made layers of vocal and instrumental music, doubling them in some cases, and also in other instances, combining them with echo and reverberation. On one level of listening the resulting music may have seemed simple and straightforward. Yet on closer inspection, Brian Wilson’s arrangements were revealed to be some of most musically adventurous and complex then in pop music. Paul McCartney and Beatles’ producer George Martin both acknowledged that Pet Sounds was the inspiration for Sgt. Pep- per’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Wilson had lots of help in making this album — from lyricists such as Tom Asher, expert studio musicians such as the famed “Wrecking Crew,” and engineers like Larry Levine. Still, Pet Sounds came to be seen as Brian Wilson’s masterwork, regarded by insiders as a significant piece studio experimentation. And not least, Pet Sounds was also a competitive prod to the Beatles.

In fact, Brian Wilson had been inspired to do Pet Sounds because of the Beatles’ Rubber Soul album, which had been released in December 1965. Said Wilson of hearing that album: “Rubber Soul was a collection of songs…that somehow went together like no album ever made before, and I was very impressed…[and] challenged to do a great album.” The Beatles, in turn, were goaded by Pet Sounds to produce Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Paul McCartney and Beatles’ producer George Martin both acknowledged that Pet Sounds was the inspiration for Sgt. Pepper’s. In 2003, Pet Sounds was ranked No. 2 by Rolling Stone magazine in its list of “The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time,”second only to Sgt. Pepper’s. The album has also be given similar lofty praise by several other surveys and music magazines, including MoJo, The Times newspaper of London, New Musical Express (NME -UK), some calling it “the greatest album in history.” Although the album cover shows animals at the San Diego Zoo, the title, “Pet Sounds” is said to derive from other factors, among them, Brian’s wish to pay tribute to Phil Spector by naming the album using his initials, and also for “Pet Sounds” meaning those sounds on the album that were Brian’s favorite or “pet” sounds.

|

Cameron Crowe on Pet Sounds  Cameron Crowe. _________________________________ Cameron Crowe, Writer/Director, “My Number One: Pet Sounds,” in Rolling Stone, “500 Greatest Albums of All Time,” December 2003, p. 104. |

Good Vibrations

Cover sleeve for the Beach Boys’ single, “Good Vibrations,” a million-seller that hit No.1, December 1966. Click for EP-CD.

“…[T]he patchwork fabric of modes, moods and melodies in “Good Vibrations” is immediately disconcerting, but that’s part of the listening thrill: not knowing, for once in a pop song, where the heck it’s headed. The flower-power verse bleeds into the doo-wop excitations before modulating into the giddy chorus of countertenor voices (“Good, good, GOOD”) that escalate almost to infinity, as if a seraph were having an orgasm. Now the scheme is repeated; but just as we think we’re on to Wilson’s plan, he steals our compass by introducing another rapturous fragment with harpsichord backing (“I don’t know where but she sends me there”) and yet another, in a slower tempo (“Gotta keep those lovin’ good vibrations a-happenin’ with her”), that appears to fade out. Then the jolt of a harmonic “Ahhh” and, one last time, we’re back in the chorus…”

Beach Boys at Capitol Records with president Alan Livingston showing off two gold records, 1964-65.

Musically, Pet Sounds and “Good Vibrations” marked a peak for the Beach Boys sound. These recordings also marked an ending of the more traditional Beach Boys era. By December 1966, Brian Wilson was exhausted and depressed. But in late 1966 and early 1967, he had set out on a next project; a next step in expanding his musical exploration in the mold of “Good Vibrations.” Musically, Pet Sounds and ‘Good Vibrations’ marked an ending of the more traditional Beach Boys era. This was a project for an album he called “Smile.” But here Brian came up against some pretty stiff resistance from Mike Love, in particular, and he seemed to back off and then retreat into drugs and depression. Missing album deadlines, Brian went into seclusion and then in and out of mental difficulty for years. From then on, although there would be flashes of the old Beach Boys’ success in the 1970s and 1980s — a few hits songs, more compilation albums from Capitol, and halting emergences of Brian Wilson’s participation and talents — the Beach Boys were never quite the same again. Infighting and lawsuits in later years would also mar their legacy. Still, for much of the public, the Beach Boys lived in memory, encased in their 1960s golden sound. In actual form too, the group would continue, though reconstituted from time to time, with Mike Love as leader, touring successfully well into the 2000s.

Later Years

Capitol’s 1981 “Beach Boys Medley” single, side A, with a four-minute mix of their greatest 1960s hit. German label shown.

On subsequent summer tours in the mid-1980s, the remaining Beach Boys, with some additional new members, could still play to huge audiences, many fans still enjoying the Beach Boys sound regardless of group composition. At Fourth of July concerts in 1984 and 1985, the Beach Boys played to huge crowds in Washington and Philadelphia — 750,000 in Washington in 1984 and one million in Philadelphia in 1985, and back to DC again that same evening in 1985 to perform for another 750,000 on the National Mall. ( The Beach Boys’ stock had been raised considerably in the mid-1980s after a political faux pax by U.S. Secretary of the Interior James Watt called them “the wrong element”and banned them from playing on the Mall — which by the next year had been reversed by none other than fans Nancy and Ronald Reagan). By 1988, the reconstituted Beach Boys had their first No.1 hit in 22 years with the song “Kokomo” which was written for the movie Cocktail starring Tom Cruise — a song written by John Phillips, Scott McKenzie, Mike Love, and Terry Melcher.

|

Capitol’s Gold Mine 1975 Spirit of America |

Through the 1990s, the Beach Boys continued to tour in America as a nostalgia act. Brian Wilson, meanwhile, appeared in a 1995 TV documentary that ran on the Disney Channel, I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times, in which he performed with his then adult daughters, Wendy and Carnie. But just as the band appeared to be pulling together for a new studio album in February 1998, Carl Wilson, a life-long smoker, died of lung cancer after a long battle with the disease. He was 51 years old. By then, Brian Wilson and Al Jardine, though still legally members of the Beach Boys organization, each pursued solo careers with new bands. Through the late 1990s, in fact, there were three different Beach Boys-connected tours — Brian Wilson had a solo tour; Mike Love lead the more or less “official” Beach Boys group, and Al Jardine had the “Beach Boys Family”group, later re-named the Endless Summer Band. ABC television in February 2000, aired a docudrama miniseries, The Beach Boys: An American Family, which gave many a view of the Beach Boys’s family life they hadn’t known before. Capitol Records was still mining the old Beach Boys music vault, and in 2000, began a reissue campaign focused on the group’s out-of-print 1970s’ LPs. In early 2004, Brian Wilson, to rave reviews in London, released the long-delayed SMiLE album — the aborted follow up to Pet Sounds which he had started but abandoned in the late 1960s. Brian continued recording, writing, and performing into the 2000s.

Yet it remained that the old days and the old Beach Boys’ sound was what emerged periodically in the post-1960s period for renewed recognition. In mid-June 2006, the surviving Beach Boys members — Brian Wilson, Mike Love, Al Jardine, Bruce Johnston, and David Marks — set aside their differences and reunited at the Capitol Records building in Hollywood. The special occasion was a celebration of the 40th anniversary of the Pet Sounds album.

Capitol Records mined the Beach Boys’ 1960s vault endlessly. Still, this “Very Best of...” offering in 2003 sold 2 million copies by June 2006. Click for CD.

The Beach Boys story though, on one level, is a sad tale. For it replays one of those human dramas in which brilliance and talent rise to an accomplished even joyous level for a short, intense period of time, then for reasons of human frailty and the whims of gods and markets, can never quite be repeated again. The Beach Boys certainly had their shining moment, with an incredible run of creative output in the 1962-1966 period. They made beautiful music then that filled the world with a brighter sound; a brightness and optimism that can still be heard today.

Beach Boys in more formal attire, 1964.

Additionally, the 2015 film about Brian Wilson, Love & Mercy, is also covered in a separate story with film trailer.

For other stories at this website on the history of popular music please visit the “Annals of Music” category page. For a listing and brief description of additional stories in the 1960s decade, visit the “1961-1970 Period Archive”. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

________________________________

Date Posted: 14 June 2010

Last Update: 9 January 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Early Beach Boys,1962-1966,”

PopHistoryDig.com, June 14, 2010.

________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Beach Boys performing at the TAMI show, 1964. |

Al Jardine & Carl Wilson at 1964 TAMI show. |

“The Beach Boys,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, New York: Rolling Stone Press, 3rd Edition, 2001, pp.51-54.

Joel Whitburn, The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits, Billboard Books, New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 8th Edition, 2004, pp. 50-51.

“The Beach Boys,” The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Induction year, 1988.

G. Cooksey and Ronnie Lankford, “Brian Wilson,” Contemporary Musicians, Encyclo- pedia.com.

“The Beach Boys,” Wikipedia.org

Robert Fontenot, “Profile: The Beach Boys,” About.com.

John Bush, “The Beach Boys: Biography,” All Music.com.

Jim Miller, “The Beach Boys”in, Anthony DeCurtis and James Henke (eds), The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock n Roll, New York: Random House, 1992, p 194.

Billy Altman, “For the Beach Boys, It Wasn’t All Platinum,” New York Times, July 25, 1993.

ABC Television, Mini-series Docu-Drama, The Beach Boys: An American Family, aired, February 2000.

Richard Corliss,”That Old Feeling: Brian’s Songs,” Time, Saturday, June 30, 2001.

Kevin M. Cherry, “Still America’s Band(s): The Beach Boys Today,” National Review, July 8, 2002.

J. Freedom du Lac, “It Wasn’t All Fun, Fun, Fun: The Beach Boy’s Hymns to the Dream State of California Belied The Nightmare He Was Living,” Washington Post, Sunday, December 2, 2007, p. M-1.

Tom Moon, “Good Vibrations, The Beach Boys,” and “Pet Sounds, The Beach Boys,” 1,000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die, Workman Publishing: New York, 2008, pp. 54-55.

Matthew Greenwald, Song Review: “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man), The Beach Boys,” AllMusic.com.

Donald A. Guarisco, “Song Review: Beach Boys, All Summer Long,” AllMusic.com

“The True Story Behind the Beach Boys’ Classic Song ‘The Warmth of the Sun’,” Forgotten Hits.com.

Laura Barton, “Hail, Hail, Rock ‘n’ Roll: With God Only Knows, Brian Wilson Wrote the Ultimate Love Song,” The Guardian, Friday, April 3, 2009.

“God Only Knows How Big Love Got Away with It. Oh Yeah: Money,” GlassShallot, August 22, 2007

“The Beach Boys Top 25 Best Most-Overlooked Singles,” Talk AboutPopMusic, Friday, October 30, 2009.

“Early Beach Boys Hit Song Topics,” #5 In A Series Of Pop-Cultural Charts, Danmeth. com, May 6, 2009.

“Surf, Rods, ‘n Honeys — Jan ‘n Dean, Part 2 of 5,” JanAndDean-JanBerry.com, viewed, May 2010.

Mark A. Moore, “A Righteous Trip: In the Studio with Jan Berry”, Dumb Angel Magazine, 2005.

“Beach Boys Will Appear July 3,” Los Angeles Times, June 22, 1965, p. C-8.

John L Scott, “Beach Boys Ride Crest of Teen Craze,” Los Angeles Times, June 28, 1965, p. C-15.

Art Seidenbaum, “The Beach Boys—Jivey in the Halls of Ivy,” Los Angeles Times, March 15, 1966, p. C-1.

Art Seidenbaum, “Beach Boys Riding the Crest of Pop-Rock Wave,” Los Angeles Times, March 20, 1966, p. B-17.

“Beach Boys” (re: March of Dimes benefit concert w/others at Merriweather Post Pavilion, Columbia, MD), Washington Post, Times Herald, July 27, 1969, p. F-7.

Tom Zito, “The Beach Boys Still Sound Good,”Washington Post, Times Herald, April 25, 1971.

Don Heckman, “Beach Boys Fans Here Demand The Old Hits, Not the New Ones,” New York Times, Sunday, September 26, 1971, p.78.

Henry Allen, “Beach Boys: Good Junk,” Washington Post, Times Herald, August 31, 1972, p. B-15.

Alex Ward, “The Beach Boys: A Rock ‘n ‘Roll Institution,” Washington Post, August 29, 1976.

Larry Rohter, “15 Years of Beach Boys,” Washington Post, January 21, 1977, p. B-8.

John Rockwell, “Beach Boys Turn Central Park Into California Dreamin,” New York Times, Friday, September 2, 1977, p. 19.

ABC-TV, Docu-drama miniseries, The Beach Boys: An American Family, February 2000.

Robbie Woliver, “Music; Finally Getting the Good Vibrations Back Again,” New York Times, September 3, 2000.

Peter Ames Carlin, “Music; A Rock Utopian Still Chasing An American Dream,” New York Times, March 25, 2001.

David Leaf, The Beach Boys and the California Myth, Grosset & Dunlap, 1978, paperback, 192 pp.

Brad Elliott, Surf’s Up! The Beach Boys on Record, 1961-1981, Pierian Press, 1992, hardcover,493 pp.

David Leaf, The Beach Boys, Courage Books, 1985, hardcover, 208 pp.

Steven Gaines, Heroes and Villains: The True Story of the Beach Boys, Dutton, 1986, hardcover, pp. 374

Brian Wilson with Todd Gold, Wouldn’t It Be Nice: My Own Story, Harper Collins, 1991.

Kingsley Abbott (ed.) Back to the Beach: A Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys Reader, Helter Skelter Publishing, October 2002, 256 pp .

Charles L Granata, Wouldn’t It Be Nice: Brian Wilson and the Making of the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2003.

Andrew G. Doe, John Tobler, Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys: The Complete Guide to Their Music, Omnibus Press, 2004, 176 pp.

Peter Ames Carlin, Catch a Wave: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson, Rodale Press, 2006, 336pp.

Philip Lambert, Inside the Music of Brian Wilson: The Songs, Sounds and Influences of the Beach Boys’ Founding Genius, Paperback, Continuum Press, Illustrated edition, March 2007, 404 pp.

The Beach Boys and Wolf Marshall, The Beach Boys Definitive Collection: A Step-By-Step Breakdown of Their Guitar Styles and Techniques, Hal Leonard Corp., 2002, 64 pp.

Phil Gallo, “Hall of Fame Flashback: The Beach Boys,” Fender.com.

Beach Boys album covers & single sleeves, Sergent.com.

Film, Brian Wilson: A Beach Boys Story, A&E Biography Series,1999, running time: 100 minutes.

_______________________