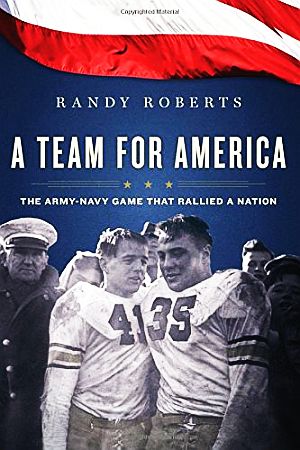

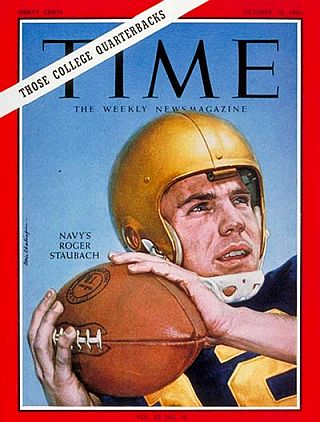

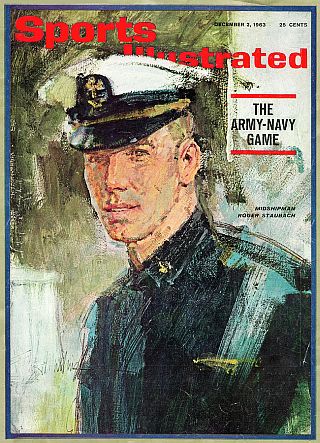

The originally-planned Nov. 29th, 1963 cover of Life magazine with Navy QB, Roger Staubach, later supplanted by JFK cover following President’s assassination (see below).

Staubach, then a junior at the Academy, was wowing the country with his football heroics that fall. Navy had gone 8-1 over its first nine games, and Staubach was seen as the leader in the Heisman Trophy race – the coveted annual award for the nation’s most outstanding college football player.

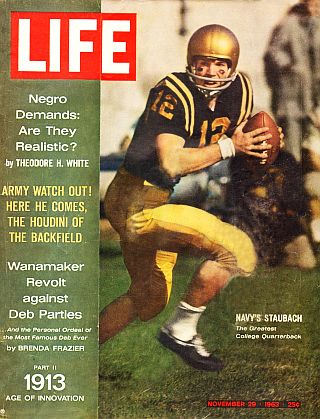

In mid-October 1963, Staubach had already appeared on the cover of Time magazine for a story featuring college quarterbacks. But by appearing on the Life cover– then scheduled for later November – Staubach would help bolster his chances for winning the Heisman, as voting would occur around that time.

Time, meanwhile, in its earlier reporting on the Navy QB had offered glowing reviews after seeing him in action against Southern Methodist University (SMU): “Quarterback Staubach put on a show that even the most jaded pro-football fan would find breathtaking to behold.”

Staubach had become a talented and elusive runner, as well as an effective passer, confounding defenders with his adept scrambling, while compiling an impressive record of completed passes, often for touchdowns.

In 1962, as a sophomore, Staubach became a starter in the fourth game, and later, in that year’s Army-Navy game, he ran for two touchdowns and threw for two more in Navy’s 34-14 rout of Army. In some ways, that was the game that put Staubach on the map as it were, made him a rising star. Army Coach Paul Dietzel had high praise for the Navy QB: “Staubach is head and shoulders above all the other quarterbacks,” he said. “He’s a beautiful, unbelievable passer; he’s a scrambler and has great split vision; he can run, and that makes it impossible to defend against him and he’s a tremendous inspirational leader.”

Roger Staubach of Navy had already appeared on Time magazine cover, October 18, 1963.

The editors at Life had worked up the expected cover layout and taglines – one of the latter appearing below the photo of Staubach, shown on the move with the ball, stated: “Navy’s Staubach: The Greatest College Quarterback.” Another, listed in a left-hand column of other story taglines, offered a warning for his upcoming opponent: “Army Watch Out! Here He Comes, The Houdini of The Backfield” – alluding to Staubach’s scrambling ability and winning ways.

Earlier in November that year, Navy’s public relations guy, Thalman, had squired a Life photographer around the Naval Academy campus at Annapolis, Maryland. And a few days before the planned issue with Staubach was to hit newsstands, Life sent Thalman three unstapled copies. The covers of those pre-publication samples were stamped “First run copy. Not completely made ready.” But in fact, the Staubach cover never made it to the newsstands, as tragedy gripped the nation on November 22nd, 1963 when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas. On that fateful day, there were 7 million copies of Life magazine with Staubach on the cover coming off the presses. Staubach, in fact, had received a copy just hours before Kennedy was killed. But all of those copies were scrapped when the tragic news broke that Kennedy had been shot.

After the assassination of President Kennedy on Nov 22, 1963, the Roger Staubach cover for Life was cancelled and replaced with one honoring the slain president, which appeared on November 29, 1963.

On November 25th, 1963, a stunned nation watched the solemn state funeral as President John F. Kennedy was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery.

The Army-Navy game, meanwhile, had been postponed, and there was some thought of possibly cancelling the game altogether, given the national tragedy. However, shortly after the assassination, JFK’s wife and first lady, Jacqueline Kennedy, urged the military academies to play the Army-Navy game. The Kennedy family also requested the game be played.

The Pentagon, in an official statement, announced Army-Navy would be pushed back a week to honor Kennedy’s memory.

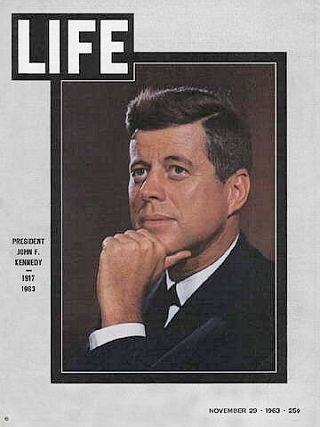

JFK was a Navy man himself, known for his WWII heroics after the Patrol Torpedo boat he commanded – PT 109 – was rammed and sunk by a Japanese destroyer in the Pacific Ocean, saving several crew members in the aftermath and awarded commendations for his actions.

But Kennedy was also an avid football fan and an especially big fan of the Army-Navy game. During his brief presidency, he had attended two previous Army-Navy games – once in 1961 and again in 1962 – officiating at the coin toss in both games. In fact, earlier in 1962, Kennedy, on his way to vacation at Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, visited briefly with Navy team members during their preseason training camp. “We met him when he would go up to … [Massachusetts],” Staubach would later explain of visiting with JFK. “We used to train at Quonset Point [Naval Station, Rhode Island] and he would come up [to Hyannis Port] in the helicopter…”

President John F. Kennedy, making coin toss, at earlier Army-Navy game in Philadelphia, PA, as representative from Army and Navy teams and others look on. Photo, Philadelphia Inquirer.

One of Navy’s previous stars, in fact, halfback and Heisman Trophy winner, Joe Bellino, had come to the White House for a brief session with President Kennedy. The President, along with his brother, Robert F. Kennedy, had attended the 1962 Army-Navy game, spending half of the time seated on the Army side, and half on Navy’s side.

President John F. Kennedy at the 1962 Army-Navy game, seated next to some Navy brass, along with his brother, Robert F. Kennedy, seated further down the row. The president spent one half on the Navy side and one half on the Army side. AP photo.

In 1963, just prior to his assassination, Kennedy was looking forward to watching the Midshipmen take on the Cadets at the annual Army-Navy game. “I hope to be on the winning side when the game ends,” he telegrammed the Navy coach on November 20th. Two days later, the president was assassinated in Dallas.

Given the intercession of Jackie Kennedy and the Kennedy family, the reset Army-Navy Game of 1963 was scheduled for December 7, 1963 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, also coinciding on that date with the 22nd anniversary of Pearl Harbor Day.

The Army-Navy game was a very popular national event, a rivalry game played sine 1890, with only a few cancellations, typically in time of war. TV coverage of the game began in the 1950s, and as of 1963, Army had won 30 times, Navy 28, with five ties. The Army-Navy game at that time was also “the national game.” Back in the 1950 and 1960s there was no Super Bowl; this was the big national game of the year, and so, quite a big deal in those years, commanding a large nationwide TV audience.

December 2, 1963, Navy midshipman and team quarterback, Roger Staubach, in his formal Navy attire, on Sports Illustrated cover.

A feature story on Stauback and the upcoming Army- Navy game covered some of the history of the game, but was quite flattering of Staubach. The story by Dan Jenkins, was titled, “A Setting For Greatness in Philadelphia,” and included a sub-heading paragraph that noted: “The Army and the Navy have met on the football field 63 times in the last 73 years. Seldom has either service possessed a star of greater magnitude than Navy’s Roger Staubach…”

Stauback, observed Jenkins, “is truly a dazzling athlete. With long, powerful strides, Staubach rolls out with deceptive speed. He throws on the run, or backing up. Trapped, he has a startling quickness and mysterious sense of the profitable direction… And it is when Staubach gets into trouble that he is at his very best. Never easy to pull down, he throws with tacklers tearing off pieces of his jersey or clawing at his legs, or he runs… He is, in the final sense, that splendid combination of runner-passer who can invest every play with unbearable excitement.”

The 1963 Game

The December 7th, 1963 game drew a capacity crowd of 102,000 to Philadelphia’s Municipal Stadium, which was later renamed John F. Kennedy Stadium – the long-standing “neutral” location that hosted some 41 annual Army–Navy games between 1936 and 1979. Before the start of the 1963 game, Navy’s coach, Wayne Hardin, brought the team together in the locker room to reveal that Roger Staubach had been awarded the Heisman Trophy. He became the fourth non-senior to win the award after accounting for 15 touchdowns and completing 107 of 161 passes for 1,474 yards and rushing for 418 yards.

Navy had won the last four Army-Navy games, and as a bit of added hype in the contest, and a pointed jab at Army, Navy had the phrase “Drive for Five” lettered across the back shoulder section of all the Navy players’ uniforms, meaning they were out to make it five wins in row over Army.

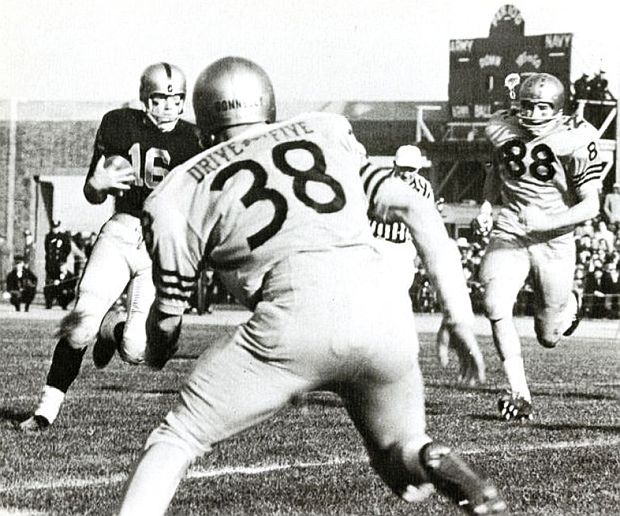

Photo of early play in 1963 Army-Navy game shows Navy QB, Rollie Stichweh on the move as Navy defenders zero in on him, with their “Drive-For-Five” jersey labeling added as extra incentive and taunt at Army players.

In the 1963 game, Staubach played a more workman-like role at QB than the scrambling star that he was, though leading the nationally-ranked No. 2 Navy team (8 and 1) in their battle with the Cadets of West Point. Army, for its part, was also nationally ranked in the Top Ten, then at 7 and 2. But it was Army’s quarterback, Rollie Stichweh, a converted halfback, who would steal the show in some ways, especially in the fourth quarter. Stichweh, in fact, led off the game with a touchdown drive, as he marched Army down field for 65 yards in eleven plays, taking the ball in for a score himself from the ten yard-line. Score: Army 7, Navy 0.

Army’s QB, Rollie Stichweh, was upended by Navy defenders Ed Orr and Johnny Sai, right, while scoring a first-quarter touchdown.

But then Navy’s Staubach went to work, using his fullback Pat Donnelly on running plays while throwing a few passes to keep the defense guessing. In the second quarter, about 10 minutes in, Staubach brought Navy to the 2-yard line, where he then sent the 200-pound Donnelly in for a touchdown, followed by the extra point kick. Score: Navy 7- Army 7, where it remained at the end of the first half.

Roger Staubach (No. 12, center) at work during the 1963 Army-Navy game, where he relied on his fullback, Pat Donnelly, for ground gains and three touchdowns.

Then in the third quarter with Staubach passing and Donnelly running, Navy went 90 yards to take the lead, 14-to-7. Later, with Navy threatening again on the 7 yard line, Army made a tough stand, holding the Middies on fourth down and inches. Yet in subsequent play, Army hurt itself with two 15-yard penalties for roughing, which helped Navy keep the momentum leading to another touchdown by fullback Donnelly. So, by the fourth quarter, with ten minutes left to play, it was Navy 21, Army 7, which put Army in a pretty deep hole.

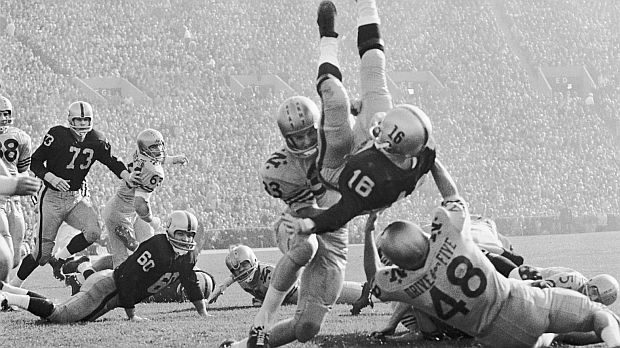

But then came an exciting Army comeback. Stichweh sent halfback Kenny Wai off tackle for a good gain. Then Stichweh himself ran wide for another gain, and then again from short yardage, jumping into the air and the end zone for a score. With 6:19 left in the fourth quarter, it was now Navy 21- Army 13.

Army QB, Rollie Stichweh (No. 16), on one of his runs in the fourth quarter, leading to a touchdown and later 2-point conversion bringing Army to within one score of tying Navy with minutes to go.

After the Navy touchdown, Stichweh surprised Navy at the extra point attempt by going for the two-point conversion, running left for the score, making it 21-to-15. Now another Army touchdown would tie the game, and an extra point would win it. So at the kickooff, Army gambled and tried an onside kick and it worked, with Stichweh — seemingly all over the field that day — recovering the ball on Navy’s 49 yard-line.

Now late in the fourth quarter, there were six minutes on the clock, enough to go 49 yards for a score. But Army had no time-outs left, and Stichweh was more of a runner than a throwing QB. Still, he moved Army down the field.

With 1:38 left on the clock, a pass completion by Stichweh gave Army a first down on Navy’s seven-yard line. The excitement generated by Army’s comeback drive brought a crush of fans out of their stadium seats down to the field, gathering along the sidelines and at the back of the end zone. The noise of the crowd, plus the yelling from the sideline fans, made it impossible for Army’s players to hear Stichweh calling the offensive signals. “You feel things closing in, and the noise level is nothing I have heard up to that point or since,” Stichweh would later recall.

With the clock ticking down, Army QB Rollie Sitchweh sends his halfback, Ken Waldrop (42) on a running play up the middle and he makes it to the 2 yard-line, just short of the goal line. But with crowd noise and no help from officials, the Cadets are having difficulty, and they can’t get off another play (AP photo).

By the time Army made it to the Navy four yard-line, there was less than a minute on the clock. The crowd roar again made it impossible for Army’s players to hear Stichweh. The referee called time-out. But Army had lost 20 seconds. Stichweh then sent halfback Waldrop to the two yard line.

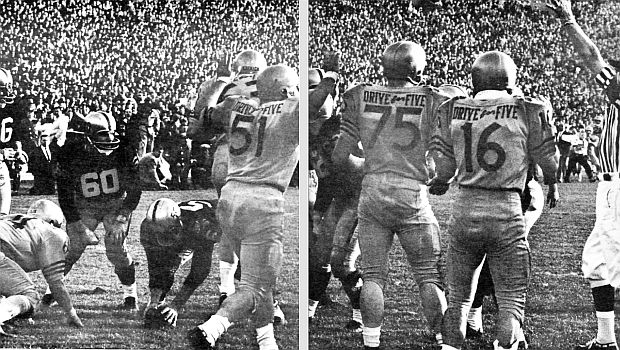

With less than 20 seconds remaining in the 1963 Army-Navy game, Army’s QB, Rollie Stichweh (No. 16) and team line up on the 2 yard-line, but with crowd noise and no help from officials, the Cadets are having difficulty hearing the signals, and they can’t get off another play.

Now there were 16 seconds left. Army quickly lined up again, but the crowd noise was impossible. Stichweh expected officials to call a timeout again, but that call did not come, preventing him from calling a play as time expired. Navy held on for the win at 21–15.

Sports Illustrated photo captures the end of the 1963 Army-Navy game, as referee at far right signals game’s end as No. 60, Army guard Dick Nowak looks on in disbelief, while Navy’s Captain, Tom Lynch, No 51 celebrates Navy win, 21-15.

Sports Illustrated would call it “Army’s Big Goof,” and Stichweh would later say the failure was his for not managing the time better. Still, it was a memorable game and Navy knew it was lucky to get away with the win. Navy coach Hardin played it low-key: “I feel awful humble,” he said after the game to reporters. “You just can’t crow over a game like this.”

But the victory for Navy clinched a Cotton Bowl invitation and a national championship showdown with the No. 1 ranked University of Texas. However, in the Cotton Bowl classic, played in Dallas, Texas on January 1, 1964 before a crowd of 73,000, Navy lost to Texas, 28-6. Navy didn’t score until the fourth quarter, on a two-yard touchdown run by Staubach, who had gone 22-for-34 passing with 228 yards. Staubach was also a first-team All-American that year and recipient of both the Heisman Trophy and equally prestigious Maxwell Trophy.

Game in Homage

The 1963 Army-Navy game, in any event, was a game that honored JFK, as Staubach would later say: “…Obviously, the game was played on his behalf, and it was very emotional — heck of a game actually. The Army quarterback, Rollie Stichweh, was fantastic. We’ve become good friends. Rollie and I talked about that game and what it meant to the country, just to see the servicemen and women at the game. Honoring the president at our game is what took place. That’s why it was such a big deal, the ’63 game. The family asked the game to be played on his behalf, so it was a special game….”The 1963 Army-Navy game was also a moment of national healing; a time when the nation came together around a sporting event, steadying the ship of state, saying in a kind of collective national voice, “things will be all right; we can weather this.”

Army’s Stichweh, too, recalled it as a special game: “The emotions really came out at the game. We had over 100,000 people there and everybody knew it was more than a football game. It was a testimony to the President of the United States and his family. The feeling was just different than any other game I ever played in.” Following the game, days later, Secretary of the Army, Cyrus Vance, sent Navy Captain, Tom Lynch, a letter containing the silver dollar President Kennedy would have used for the coin toss at the start of the game.

The 1963 Army-Navy game was more that just a football game. It was also a moment of national healing; when the nation came together around a sporting event, steadying the ship of state, and saying in a kind of collective national voice, “things will be all right; we can weather this.” And in subsequent bad times, as well, there have also been similar occurrences of American sporting events lifting or comforting the nation after adversity or sorrow of one kind or another – as in the New York Yankees-Arizona Diamondbacks World Series games of September-October 2001 played in New York City following the World Trade Center bombings of 9-11; or in September 2006, some months following the devastation of Hurricane Katrina, when the New Orleans Saints football team returned to the restored New Orleans Superdome that had been the scene of much sorrow and destruction, lifting that city and nation; and also in April 2013 at the Boston Red Sox baseball game played at Fenway Park following the Boston Marathon bombings, signaling the resilience of that city and nation.

Legacy

The 1963 Army-Navy game also garnered subsequent media attention in later years. One book written on the 1963 game by Boston Herald sports reporter, Michael Connelly, titled, The President’s Team: The 1963 Army-Navy Game & The Assassination of JFK, was published in 2009, with a forward by then Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy. In addition to the book, in November 2013, CBS-TV aired a 50th anniversary documentary film on the game, “Marching On: 1963 Army-Navy Remembered.”

A poster for the 2013 CBS-TV documentary special, “Marching On: 1963 Army-Navy Remembered”. |

Another film on the 1963 game was said to be in production by Michael Meredith, son of Dallas Cowboys football legend and broadcaster, Don Meredith. That project, with the working title, “The President’s Team” — was planned to focus on the 1963 Navy team and the brotherhood formed among its members, with Staubach as a central figure.

Historian Nicolaus Mills’ 2014 book, “Every Army Man is With You,” features Army players who won the 1964 Army-Navy game and served in Vietnam. Click for copy.

In 1964, with Stichweh and Staubach as seniors, the teams would meet again in the 1964 Army-Navy game. That game was a key test for Army, now facing the Heisman-winning Staubach for a third time, and having lost to Navy five years in a row. Staubach had had a rough 1964 season, sustaining a foot injury that cost him half the season, though he played in the Army-Navy game.

But in this game, with five of its starters playing offense and defense, Army rallied to an 11-8 triumph over Navy, receiving national news coverage. In that game, Calvin Huey of Navy became the first African-American to play in the series.

In later years, seven of Army’s players from the 1964 game were featured in the 2014 book, Every Army Man Is With You, by Nicolaus Mills, which chronicles the Army teammates’ story as they went from West Point and the football field, to Vietnam, and back home again. Stichweh served five years in Vietnam with the 173rd Airborne Brigade. He was later inducted into the Army Sports Hall of Fame in 2012, with Staubach attending. The two former rivals remained friends throughout their subsequent careers. Stichweh had a successful career in business management and married his wife Carole, having three children and nine grandchildren.

Staubach & Cowboys

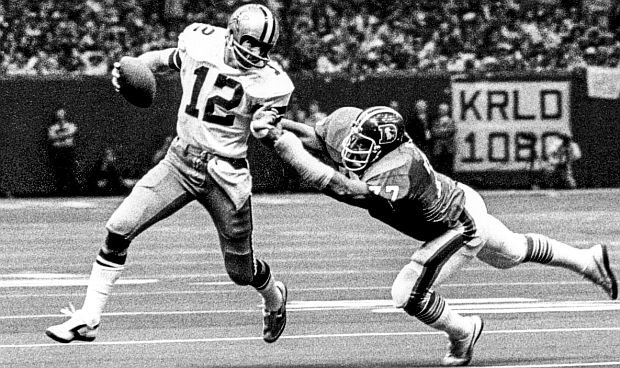

As for Staubach, the Naval Academy retired his jersey, No. 12, during his graduation ceremony after his senior season. Staubach finished his Academy sports career as captain of the school’s 1965 baseball team. In 1981, he was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame, and in 2007, ranked No. 9 on ESPN’s Top 25 Players In College Football History list.

After graduation Staubach served in the U.S. Navy, including a tour of duty in Vietnam. In 1969, following his military service, he joined the NFL’s Dallas Cowboys pro football team which had drafted him in 1965. He would play with Dallas during all 11 seasons of his pro career. He led the Cowboys to the Super Bowl five times, four as the starting quarterback, including victories in Super Bowl VI and Super Bowl XII. He was named Most Valuable Player for Super Bowl VI, and became the first of four players to win both the Heisman Trophy and Super Bowl MVP.

Roger Staubach of the Dallas Cowboys, continuing his scrambling ways in his pro career, shown here alluding the grasp of a Denver Bronco’s defensive lineman sometime in the 1970s.

Staubach retired from pro football in March 1980 with the highest career passer rating in NFL history at the time, 83.4, and was voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1985. He recorded the highest passer rating in the NFL in four seasons (1971, 1973, 1978, 1979) and led the league with 23 touchdown passes in 1973. Overall, Staubach finished his 11 NFL seasons with 1,685 completions for 22,700 yards and 153 touchdowns, with 109 interceptions. He also gained 2,264 rushing yards and scored 21 touchdowns on 410 carries. For regular-season games, he had a .750 winning percentage. He was an All-NFC choice five times and selected to play in six Pro Bowls (1971, 1975–1979).

In 2010, Staubach was named the No. 1 Dallas Cowboy of all time according to a poll conducted by the Dallas Morning News. In November 2018, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom at the White House.Roger Staubach married his wife Marianne in September 1965 and together they had five children As of 2017, they also counted 15 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

In his non-football professional life, aside from brief sportscasting and celebrity advertising, Staubach built a successful real estate business in the Dallas-Forth Worth area, which he later sold to the global real estate firm Jones Lang LaSalle in 2008 for $613 million.

For additional football and other sports stories at this website see the “Annals of Sport” category page. Additional stories on JFK and other Kennedys can be found at the “Kennedy History” topics page and the “Politics” category page.

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing, and continued publication of this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

______________________________________

Date Posted: 9 December 2022

Last Update: 9 December 2022

Comments to:jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/PopHistoryDig

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Roger & The President: November 1963,”

PopHistoryDig.com, December 9, 2022.

______________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“Army–Navy Game,” Wikipedia.org.

“1963 Navy Midshipmen Football Team,” Wik-ipedia.org.

“1963 Army Cadets Football Team,” Wikipedia .org.

“College Football: Jolly Roger,” Time, October 18, 1963.

Leonard Koppett, “Army-Navy Game Postponed to Dec. 7; Usual Ceremonies Will Be Eliminated; Decision Is Made by the Pentagon; Possible Cancellation Plans Are Dropped at Request of Kennedy’s Family; Presidents Frequently There; Preparations in Progress,” New York Times, November 27, 1963, p. 44.

United Press International, “Staubach to Get Heisman Trophy; Navy’s Quarterback Named for Highest Award in Football; Best Passing Percentage; What’ll He Do? Second Time Around,” New York Times, November 27, 1963, p. 44.

John Kelly, “Near the Anniversary of JFK’s Death, the Most Famous Magazine Cover That Never Was,” Washington Post, November 20, 2013.

“The President Who Loved Sport,” Sports Illustrated, December 2, 1963, pp. 20-21.

Dan Jenkins, “A Setting For Greatness in Philadelphia,” Sports Illustrated, December 2, 1963, pp, 32-34, 37.

“Army’s Future is Still Ahead,” Sports Illus-trated, December 2, 1963, p. 34.

Red Smith, “Five for Navy, 21-15,” The New York Herald Tribune, December 1963.

Sandy Grady, “Dietzel’s New Bandit-Stichweh; Rollie the Robber Baron Almost Heisted Victory,” Philadelphia Bulletin, December 1963.

“College Football: I Feel Awful Humble,” Time, December 13, 1963.

Dan Jenkins, “Two Yards and The Clock; They Were All That Stood Between Army and the Upset of the Year But Navy and Confusion Won Out,” Sports Illustrated, December 16, 1963.

“Army-Navy Classic: When Staubach Hung His Jolly Roger on Army’s Chinese Bandits; The Day The Unsung Navy Sophomore, Roger Staubach, Turned Into a Star Back at Army’s Expense,” Great Moments in Sports (magazine), December 1963, pp. 29-33.

George Vecsey, “Friendships Wrapped in the Army-Navy Rivalry,” New York Times, September 26, 2012.

“Marching On: 1963 Army-Navy Remem-bered,” Vimeo.com (7:39 video re: JFK and Army-Navy game).

Mike Reynolds, “CBS Sports Network Recalls JFK, 1963 Army-Navy Game,” NextTV.com, November 13, 2013.

Hank Gola, “How 1963 Army-Navy Game Helped Nation Heal from Death of President John F. Kennedy,” New York Daily News, November 22, 2013.

“JFK Tribute: 1963 Army-Navy Football Game Honored Assassinated President,” YouTube .com (5:00), Posted by CBS Mornings, November 44, 2013.

Bill Wagner, “In 1963, Army-Navy Game Helped a Nation in Mourning Move On,” CapitalGazette.com (Annapolis, MD), Decem-ber 8, 2013.

“Staubach Reflects on His Eventful Season with Navy Football in 1963,” Washington Post, December 13, 2013.

Chip Patterson, “Staubach Leads Navy Over Army in 1963 Game Pushed Back After Assassination of JFK,” CBSsports.com, December 9, 2016.

Nicolaus Mills, “In the Wake of JFK’s Death, Remembering the Army-Navy Game of 1963 Game Day,” TheDailyBeast.com. April 14, 2017.

“Cowboys Legend’s Son Directing Navy Football Doc About Game Days After JFK Assassination,” TMZ-Sports/TMZ.com, October 25, 2018.

Tom Shanahan,“ Rollie Stichweh Offers Pointers for Playing in Army-Navy Game Altered by History but No Points for His Old Rivals,” TomShanahan.report, December 10, 2020.

SI Staff, “Army vs. Navy 1963: Remembering Kennedy,” Sports Illustrated (video, 1:26), November 15, 2013.