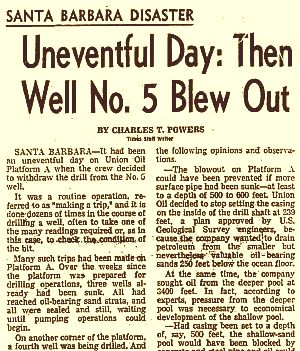

Feb. 6, 1969: Front-page headlines from the Los Angeles Times on about the 10th day of the Santa Barbara oil spill.

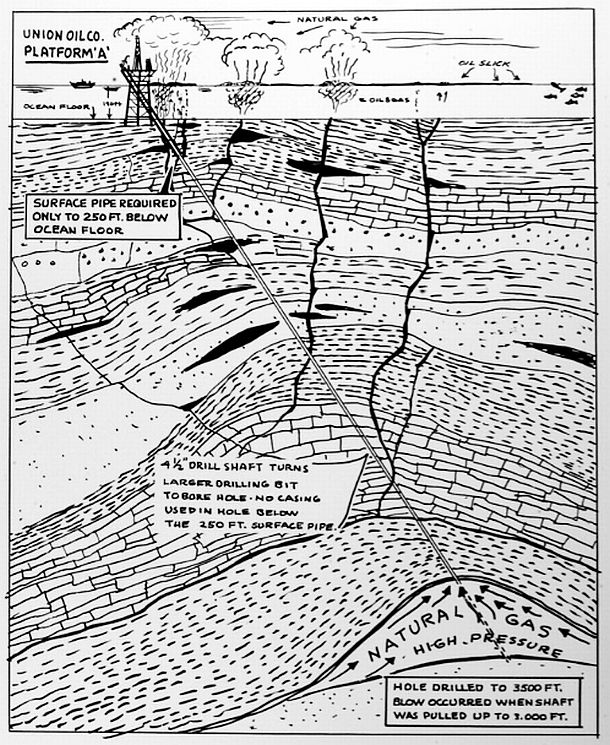

At one point, shortly after the blow out, a capping action at the well head on the platform appeared to have staunched the worst of the problem. However, complications down the well shaft due to insufficient well casings led to further problems: oil and gas escaped through the sides of the well bore and at several locations on the seabed floor below the rig. Nearby, on the water’s surface, oil and gas “boil ups” as they were called, could be seen, signaling the bigger problems below.

The worst of the spill would continue for 11 days, with lesser leaks continuing for months thereafter. Sea birds, seals, dolphins, kelp beds, and miles of beaches were coated with black crude. In the end, an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 barrels of oil were spilled and some 30-to-35 miles of California coastline tarred.

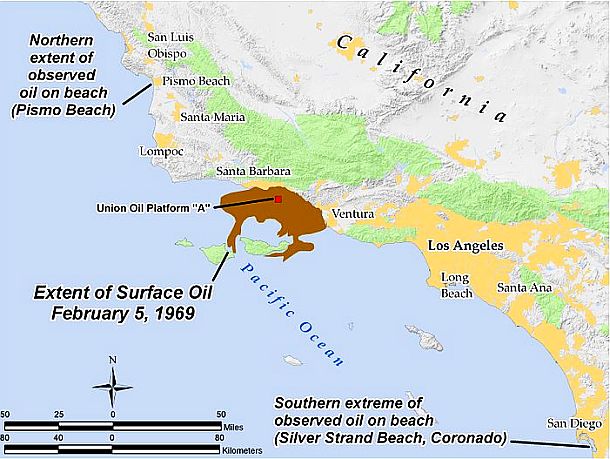

As the crude escaped during the blowout and from sub-surface releases it was spread over hundreds of square miles of open water by winds and swells. After a few days at sea, incoming tides brought the thick tar to beaches and towns along Santa Barbara County’s spectacular coastline, including: Goleta, home of University of California at Santa Barbara; the harbor at Santa Barbara; the coastline at Carpinteria; Rincon Point, the famous surfing beach; and Ventura. The farthest effects of the spill extended to Pismo Beach north of Santa Barbara, and south to the Silver Strand Beach at San Diego. Some beaches were spared the worst, as offshore kelp forests kept much of the crude from coming ashore. But a considerable length of California coastline, as well as coves and offshore islands, were hit by the spill. Frenchy’s Cove on Anacapa Island was hit, as well as beaches on Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel Islands.

Map showing the extent of the Santa Barbara Oil spill’s surface oil and initial coastal impact as of February 5th, 1969, and later, the spill’s longer reach north to near San Luis Obispo, and as far south as San Diego.

As of this writing, the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill ranks as the third worst U.S. spill, with only the 2010 BP/ Deepwater Horizon Gulf of Mexico blowout, and the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil tanker spill off Alaska, ahead of it, ranking respectively as the nation’s No.1 and No. 2 spills. But for California’s offshore waters, the 1969 Santa Barbara spill remains the largest oil spill to date. (Recently, another oil spill near Santa Barbara occurred in May 2015 at Refugio State Beach, this one from a corroded pipeline, releasing 3,400 barrels of crude oil into the area, with impacts on several marine protection areas).

Dec 1968: President-elect Richard Nixon meeting with Walter Hickel, Nixon’s choice for Secretary of the Interior.

At the time of the spill, Republican Richard M. Nixon had just taken office as President of the United States following a tumultuous year and a fractious national election. Nixon, however, was not a politician predisposed to environmental protection – especially if costs to business were involved. But he knew how to deftly exploit what was served up to him. And in this case, the events of the day, plus the prospect of Democratic presidential rivals in the Congress seizing the environmental moment, made him an unlikely “environmental president” of sorts, signing laws and creating agencies that would be among the federal government’s first meaningful actions on environmental protection. More on these later. Still, no incident would figure more prominently in whipping up the media and popular environmental sentiment than would the Santa Barbara oil spill. And it would be these tides of popular sentiment and political pressure that would sweep Nixon and others along, moving them to action.

Spill Events

2006. Platform A, shown some years later in the Santa Barbara Channel. Note small boat of fisherman at right.

Although some of the men tried to screw down a blowout-preventer, the pressure of more than 1,000 pounds per square inch was too overwhelming. Most of the workers were then evacuated from the platform due to the danger of explosion from the blow out’s natural gas.

A few workers remaining behind tried to close the well from the top by forcing the a very long piece of drill pipe back down into the well shaft and crushing it closed at the top with what are called “blind rams,” enormous steel blocks slammed together at the top of the well to stop any further blow out – at least at the platform level. This occurred at about thirteen minutes from the time of the initial blowout.

After the well was plugged on the rig, the high-pressure oil and gas then began escaping below the water, through the sides of the well bore, forcing ruptures in the sea floor 200 feet below, seen here as surface bubbling. During the spill, a slick of some 800 square miles would form on the water.

The first report on the spill from Union Oil came into the U.S. Coast Guard about two and a half hours after the blowout, with the Union Oil official saying that no oil was escaping and also at that time declining an offer of help. But on the next morning, via reconnaissance by a Coast Guard helicopter, a huge slick was revealed, extending several miles from the rig, with an estimated 75 square miles of ocean then covered by the oil. After early local news reports of the spill surfaced, Union Oil was besieged with calls. Company officials confirmed the spill, but vice president John Fraser assured reporters and local officials that the spill was small, with a diameter of 1,000 to 3,000 feet, and would be quickly controlled. He also estimated the spill rate was then 5,000 gallons per day, which later reports estimated was actually more like 210,000 gallons per day in the first days of the spill.

Jan-Feb 1969: Union Oil offshore platform in the Santa Barbara Channel off California shows oil & gas eruptions, or “boil ups” during blow out, polluting ocean and Channel, and later, California harbors and beaches.

At this point, the growing slick was still offshore, and local weather and winds would prevail to keep the oil at sea for several days. Back on the Union Oil’s Platform A, work continued on the rig to further plug the well and the sea floor fissures that had developed with the blow out. More drilling muds were used in hopes of dealing with both problems. Additional sea floor eruptions had also occurred in the vicinity of the Union Oil rig. Famous oil disaster man, Red Adair, had been brought in to help with the blow out. A drilling barge from Los Angeles had also arrived to start boring a “relief hole” to a point near the bottom of the well shaft, such channel to be used to apply drilling muds to the well and sea-bed eruptions. The Santa Barbara community meanwhile, having been quite involved in the earlier debates on oil leasing in the Santa Barbara Channel, and fearful about the impact of increased oil drilling there, was taking something of a “we-told-you-so” posture, and angered to the core.

Santa Barbara

In 1969, Santa Barbara, with a population of about 70,000, was a town filled with artists, university students, surfers, and attentive citizens. It was also a tourist destination, and was known in part for its Spanish heritage and Mission-style architecture. With a Mediterranean climate and the backdrop of the Santa Ynez Mountains, it was sometimes called the “American Riviera” – an idyllic coastal enclave. However, Santa Barbara was no stranger to oil development. Oil drilling had occurred in neighboring Summerland dating to the 1890s, on land, and also from about 1902, extending just offshore from land-based piers. Most of this activity, however, had ceased by the 1940s.

Santa Barbara, California, set between the Pacific Ocean and the Santa Ynez Mountains, is truly one of the most beautiful areas of the United States.

Following WWII, new oil exploration occurred in the Santa Barbara Channel, with oil companies using explosives in seismic exploration, angering local fisherman. The first offshore rigs appeared in the Channel in 1958. However, ten years later, in 1968, a major expansion occurred. The administration of Lyndon Johnson, then seeking a way to finance a costly Vietnam War without raising taxes, invited oil companies to bid for leases on more than 450,000 acres of oil and gas tracts in the Santa Barbara Channel. The industry paid $624 million for 70 leases. Many in the community had objected to the government’s auction of oil-drilling rights off Santa Barbara, fearing the worst. They predicted oil spills and warned that drilling in the area would mar the beauty of their coastal community and threaten its economy. At the time, as today, both federal and state governments had jurisdiction in offshore waters – states extending to three miles out, and federal jurisdiction beyond that. In 1969, the Union Oil platform was on a federal lease administered by the U.S. Department of the Interior. And within a few days of the blow out, Richard Nixon’s new Secretary of the Interior, Walter J. Hickel, would make a visit to Santa Barbara.

Hickel’s Visit

Feb 4th, 1969: Fresno Bee front page – “5 Firms Halt Sea Drilling After Request By Hickel” – also has photo of Hickel holding in-flight press conference w/ reporters.

– Walter J. Hickel, Feb 1969 Union Oil’s platform by then was shut down by the company, save for actions taken to control the spill.

But later that day, at the Santa Barbara Biltmore hotel, Hickel met with executives of six oil companies and a spokesman for California Gov. Ronald Reagan. Several of the companies also had operations in the area. But Hickel left for Washington that day without issuing a formal order to shut down of operations in the Channel, leaving open voluntary actions by the companies. Hickel at the time was uncertain of his legal authority to order a shut down and would seek further guidance from the Justice Department when he returned to Washington. Still, with his visit, Hickel appeared troubled by the oil and gas escaping from the sea bed eruptions he saw earlier that day. “It has become increasingly clear,” he said, at one point, “that there is a lack of sufficient knowledge of this particular geological area.” But Hickel would return to Washington to consider what to do next. It was February 4th, 1969, and the vast slick of oil floating out on the sea – now some 800 square miles in dimension – had not yet hit the Santa Barbara coastline. But the weather had changed and a storm was brewing. Very soon, the full impact of the spill would become shockingly apparent on the beaches of Santa Barbara.

Rough, generalized sketch of subsurface geology beneath Union Oil’s drilling platform illustrating how underground pressure forced into bore hole without casing allowed for escaping oil and gas, sea-bed ruptures, and “boil ups” of pollution on the water’s surface. Source: Dick Smith photo collection, UCSB, 1969-1971.

Oil Comes Ashore

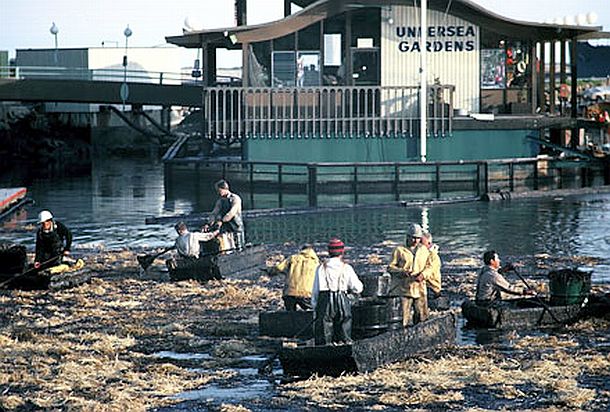

With a storm of February 4th, the oil spill that had been offshore, began moving toward the coastline. Oil containment booms had been placed in some locations to protect harbors and beaches. Yet behind these booms, oil from the spill was up to 8 inches deep. With the storm’s arrival, the booms failed. By the next morning at Santa Barbara, the stink of crude oil was thick in the air and the sight of blackened beaches with dead and dying birds was part of the scene. Oil had accumulated on shore in some places to a depth of six inches. Some reports described oiled seagulls, flopping helplessly in the muck. Others noted hearing a muffled surf sound, unlike the normal crashing of regular surf, as a thick-as-molasses oil tide washed in. Santa Barbara harbor was several inches deep in crude oil, as most of its 800 moored boats became blackened by the incoming tide. Some residents were evacuated due to the risk of explosion from hydrocarbon vapors. Oil workers and clean-up crews in two-man skiffs with waste barrels between them, were soon at work trying to skim and soak up the spill using hay and pitchforks.

Feb 1969: Clean-up crews working in Santa Barbara Harbor trying to soak up thick deposits of oil with straw thrown on the pollution after oil arrived there and 35 miles of coastline from the blow-out at Union Oil’s offshore rig. Bob Duncan photo.

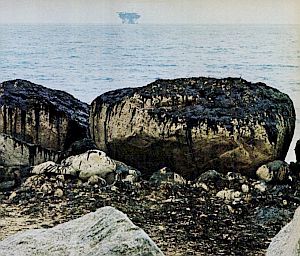

Skimmers worked at sea trying to scoop oil from the water’s surface; Union Oil activated a skimming boat with a V-shaped collector at one point, dumping the collected oil into barges. In the air, planes dumped chemical dispersants and detergent on the oil-covered ocean in an attempt to break up larger slicks. On the beaches and in the harbors, straw was spread on oily patches in an attempt to soak up the pollution. Bulldozers were also at work on the beaches pushing polluted sand and oil-soaked straw into haul-away piles. Over the course of the clean up, more than 5,200 large dumptruck loads of oil wastes, oiled beach sand, and other oiled debris were hauled to landfill sites. Oiled rocks in some locations were steamed cleaned, with the unhappy effect of “cooking” limpets, mussels and other marine life that attach to coastal rocks.

February 1969: Cleanup scene in Santa Barbara, California following oiled beaches there from Union Oil blowout. Note black oil stain on jetty rocks at the top right portion of this photo. Bob Duncan, photo, via Flickr.com.

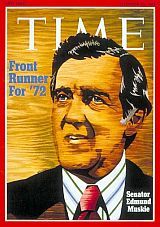

In Washington on February 5th, 1969, the U.S. Senate Public Works Subcommittee on Air and Water Pollution, under the direction of Senator Edmund S. Muskie (D Maine), then working on water pollution legislation, held one day of hearings on the Santa Barbara oil spill. Among those testifying was George Clyde, a member of the Santa Barbara County Board of Supervisors and Fred Hartley, president of Union Oil. “I am always tremendously impressed at the publicity that the death of birds receives vs. the loss of people in our country in this day and age,” Hartley said during the hearing, noting there had been no loss of human life from the Santa Barbara blowout. “Relative to the number of deaths that have occurred in this fair city [Washington DC] due to crime … it does seem that we should give this thing a little perspective.” Hartley also rejected calls to halt offshore drilling in the Santa Barbara Channel, suggesting such strategy extreme and not necessary. Secretary Hickel by this time had been assured by U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell that he did have authority to order a shut down of oil operations in the Santa Barbara Channel. Late on February 6th, President Richard Nixon announced a complete cessation of drilling in the federal waters of the Santa Barbara Channel, excepting the relief well then being drilled.

1969: Oil-stained coastal rocks in the Santa Barbara area following the January 1969 blow out at Union Oil’s offshore oil rig vividly show resulting oil pollution left behind once the tide has receded. Marvin Moore photo.

The cleanup of beaches and coastline that began in February 1969 became an ongoing project, running for months. As some areas were cleaned, huge waves of newly spilled oil would foul them again. And despite attempts by Union Oil workers to cap and cement the cracks on the ocean floor, leaks would continue from these fissures at varying rates at least into 1970. At one point, Union Oil, joined by Mobil, Texaco and Gulf – companies which also had wells on platform A – embarked on a $50,000 public relations effort, funding TV advertising by the Santa Barbara Chamber of Commerce aimed at showing the public that the town, its beaches, and its resort facilities were as attractive as ever. Still, there was no denying that the spill had been an environmental and ecological travesty.

This Associated Press photo of two oil-coated grebes (poor photocopy used here) ran with wire stories on the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill that appeared across the country.

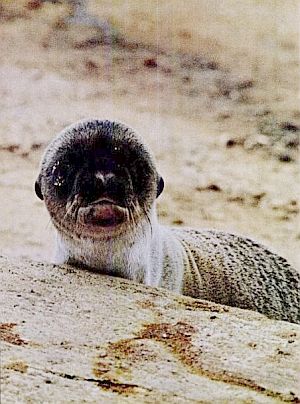

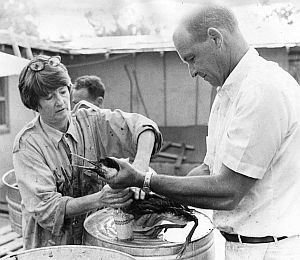

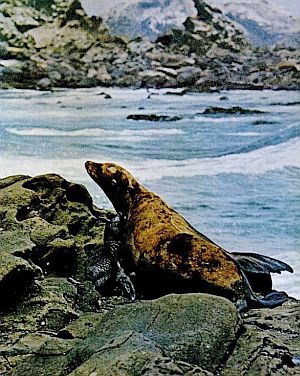

During the spill, the toll taken on birds and other wildlife was considerable. Animals that depended on the sea were hard hit. Incoming tides brought the corpses of dead seals and birds. Oil had clogged the blowholes of some dolphins, which caused their lungs to hemorrhage. Other animals that ingested the oil were poisoned. Wildlife rescuers at one point counted some 3,600 dead ocean-feeding seabirds. A number of poisoned seals (or sea lions) and some dolphins were also removed from the shoreline. The spill also killed innumerable fish and intertidal invertebrates, ruined kelp forests and also displaced many populations of endangered birds. Lobster and crab fishermen retrieving their pots from the channel found their catch alive, but completely covered with oil.

John McKinney, who would later become a Californian nature writer, was a teenager in 1969 when the spill occurred, and had gone to the site to help rescue oiled birds. “Right here and everywhere else on the coast it was black tar,” McKinney said in an interview some years later, then gesturing to a swath of beach that was then impacted. “It was thick, black tar covering everything.” McKinney was a 16-year-old high school student and boy scout living in Los Angeles then. When he heard the first reports of the spill, he jumped into his 1963 Dodge Dart and headed north to Santa Barbara. Thousands of others would also volunteer to help clean up the spill. “It was my job to wander through the muck on these beaches and pull screaming birds from the tar,” he explained in his interview. “I pulled out some birds alive, but many more were dead. Muirs, grebes, gulls, pelicans – all dead or dying.” An estimated 10,000 ?? birds were killed by the toxic mess, along with unknown and uncounted numbers of seals, sea lions, otters and dolphins.

May 1969: Sea lion pup stained by the oil spill on San Miguel Island, off Santa Barbara. Photo, Harry Benson, Life magazine.

…The Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post, the Boston Globe, and Time ran photographs of the rig, the slick, the makeshift oil booms, the beaches, and volunteers and workers bathing oily grebes (diving birds that spend almost all of their time in water). Newsweek included a dying cormorant (a coastal seabird), along with workers raking up oil-absorbent straw. Life published images of two grebes, one dead, one being bathed. Reports and images emphasized a sense of tragic, heartbreaking helplessness. Volunteers watched, the Los Angeles Times reported, as cormorants “tried vainly to clean one another off with their beaks,” and then died from ingested oil. Fleeing well-intentioned rescuers, birds headed into the surf. “Falling into the black liquid,” the report read, “they lay in the ooze, crying weakly.” In June Life covered the spill’s effects with photographs from San Miguel Island off the coast. Pictures included an oil-drenched seal pup stranded in slippery rocks. The island, the reporter wrote, provided “the black vision of the dead world which may come.”

27 Feb 1969: As oil pollution from the Union Oil blow out continued by way of the sea-floor releases, the Los Angeles Times reported on “more oil ashore.”

On the issue of oil spills generally, there had been earlier media coverage of the 1967 Torrey Canyon oil tanker spill in the Atlantic Ocean off France and England. The Torrey Canyon was a super tanker type vessel that ran aground between France and England, fouling miles of shoreline in both countries as the ship broke apart. In the wake of that spill, the Johnson Administration had asked for a review of U.S. spill contingency preparedness, leading to a joint report from the U.S. departments of Interior and Transportation, which concluded: “This country is not fully prepared to deal effectively with spills of oil or other hazardous materials – large or small – and much less with a Torrey Canyon type disaster.” And that conclusion became apparent on the coastline of California.

Protest & Politics

On February 7th, 1969, U.S. Senator Ed Muskie (D-ME), author of a then pending water pollution bill in Congress, was scheduled to make an aerial inspection of the slick. A large group of local citizens had gathered at the local airport with protest signs to greet Muskie and seek his help on arrival. It so happened that day that Union Oil’s Fred Hartley had also arrived at the airport, where he was met by the gathered citizens and a local news reporter and camera crew trying to interview him on his company’s oil spill.

Feb 7th, 1969: Union Oil president Fred Hartley, foreground, backs away from a TV reporter after having words with him in Santa Barbara, CA. Hartley, on arrival at the airport, unexpectedly ran into crowd of hostile pickets angry about the oil spill. Pickets were then waiting for Sen. Edmund Muskie. Harold Filan / AP photo.

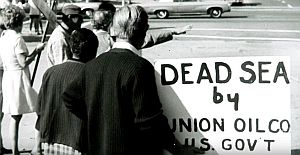

Well before the 1969 spill, Santa Barbara residents had been active in raising objections to continued leasing in the Santa Barbara Channel. And as oil began washing up on their once-pristine beaches and killing wildlife, they became outraged. But their anger was well-organized and sophisticated. Santa Barbara was not your average American community. Of its then 70,000 residents, a disproportionate number were upper class and upper middle class – later described by one writer, Harvey Molotch of the University of California, as “worldly, rich, well-educated persons—individuals with resources, spare time, and contacts with national and international elites…”

1969: A portion of a Santa Barbara crowd rallying to protest offshore oil during the time of the Union Oil blowout and resulting coastline and harbor damage. Bob Duncan photo, via Flickr.com.

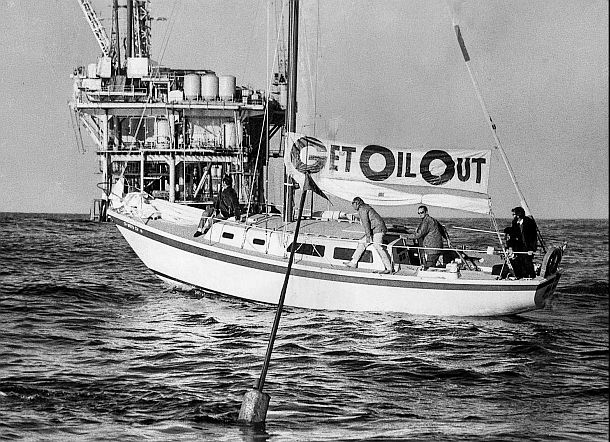

Faced with an assault on their lovely seaside town and way of life, these Santa Barbarans set out to make things right. And in short order they became active and political. They held protests, signed petitions, and demanded a ban on offshore drilling. They rallied supporters by staging plays and singing protest songs. Some mailed vials of oil to lawmakers. They formed new environmental groups – one named “Get Oil Out!” or “GOO” for short, and another under the banner of Santa Barbara Citizens for Environmental Defense. Their local newspaper, the Santa Barbara News-Press, with reporters such as Robert Sollen, became an incessant and prominent voice in the Santa Barbara fight to rid their community of oil. During the spill, hundreds of letters-to-the-editor appeared, offering reaction, opinion and recommendations. In Congress, legislation to ban drilling was introduced by their U.S. politicians, Senator Alan Cranston, Democrat, and Rep. Charles Teague, Republican. Lawsuits were also filed the city and County of Santa Barbara against the oil companies and the federal government seeking $1 billion in damages.

But beyond this Santa Barbara fight, there was a much bigger audience and a much bigger national issue. And just down the road from the fouled beaches and struggling wildlife was the Los Angeles news community, which gave the disaster an instant national conduit – soon appearing on nightly news TV broadcasts in every American living room. The Santa Barbara oil spill was soon fueling a growing national environmental sentiment that was already on the rise. In 1962, for example, Rachel Carson’s book on the dangers of chemical pesticides, Silent Spring, also became a primer on ecology. By the mid-1960s, a number of major cities had increasing auto-induced urban smog and air pollution problems, while others were battling a highway building frenzy that cleared away housing, parks and urban landmarks at will. Severe water pollution of lakes, rivers and harbors was also found all across the country. In fact, six months after the Santa Barbara spill, in June 1969, the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland caught fire, due in large part to oil and chemical pollution. Events beyond the U.S. – such as the 1967 Torrey Canyon oil spill off France and England previously mentioned – also figured into a new environmental calculus.

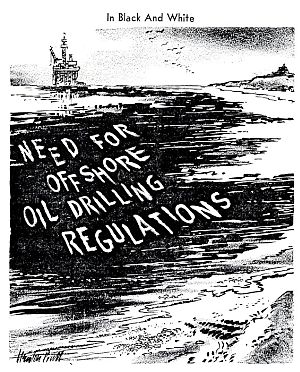

1969, The Sacramento Bee: During the Santa Barbara oil spill, editorial cartoons such as this one by Newton Pratt, citing a need for offshore oil drilling regulations, would appear in various newspapers across the nation.

Offshore Regs

In the immediate aftermath of the spill, the Nixon Administration and Interior Secretary Hickel did take some steps to address shortcomings in offshore oil policy. On February 6th, the Administration pledged to develop stringent new regulations for offshore oil drilling and also announced a moratorium on new Federal oil leases in California’s Santa Barbara channel. An order by Hickel on February 7th, shut down all oil operations on federally-owned leases in the Channel.

On February 11, 1969, Nixon requested that his science advisor, Dr. Lee DuBridge, appoint a panel to study the Union Oil blow-out and the spill. Then on February 17th, in something of surprise move, Secretary Hickel made oil companies on Federally leased offshore lands liable for all pollution cleanup costs and damages resulting from drilling operations. Hickel’s action amended existing regulations. In late February 1969, Hickel reiterated that stand when he testified on water pollution control legislation then pending in Congress, also urging the Senate subcommittee to remove the limit then in the bill on oil spill liability.

A few weeks later, on March 10, 1969, former Secretary of the Interior under Lyndon Johnson, Stewart L. Udall, also testified before Ed Muskie’s U.S. Senate subcommittee then considering water pollution legislation. Udall stated that he bore responsibility for authorizing drilling in the Santa Barbara Channel, having made the decision under pressure from the Bureau of the Budget to obtain more tax revenues from oil companies. Udall called the decision a “sort of conservation Bay of Pigs,” drawing a parallel to the U.S. fiasco of 1961 when an American-backed invasion force seeking to overthrow Cuba’s Fidel Castro was humiliated in battle and mostly captured at the Bay of Pigs invasion site in southern Cuba. As for Santa Barbara lease, Udall said, the possibility of a blowout occurring there was never raised as a major issue. “As I look back,” he told the committee, also offering his support for tighter offshore regulation, “we were overconfident concerning the risk involved.”

By late March 1969, as Hickel and Interior continued working on updating offshore oil regulations, President Nixon decided to visit Santa Barbara.

March 21, 1969: President Richard Nixon (hands in pocket, center) walks on Santa Barbara beach with reporters. |

Headlines from the “Santa Barbara Press-News” on Nixon’s visit and that he would consider a permanent ban on drilling. |

March 21, 1969: President Richard Nixon greeting oil spill workers cleaning up the beaches in Santa Barbara. |

Nixon Visit

On March 21st, nearly two months after the blow out, President Richard Nixon came to Santa Barbara as cleanup efforts were underway. He arrived at the Point Mugu Naval Air Station earlier that day, then took a helicopter tour of the Santa Barbara Channel and the spill area. The helicopter transporting Nixon dipped close to the water so the President could see patches of spilled oil still on the water. They also flew near oil-stained Anacopa and Santa Cruz islands, as well as Union Oil’s Platform platform six miles offshore where residual bubbling was still visible

After the helicopter tour, he visited a mostly cleaned-up beach in Santa Barbara along with an entourage of reporters. “This problem is bigger than just Santa Barbara, “ he said. “We need more effective control to protect out beauty and natural resources. I don’t think we’ve paid enough attention to this” Nixon also noted he had visited “these beautiful beaches” as a boy, adding “I feel we must preserve these beaches… preserving beaches is more important than economic considerations.”

Nixon shook hands with some of the cleanup crew working there. As he did, some protest chanting could be heard from a small crowd about 100 yards away, saying, “Get oil out! Get oil out!…” Nixon said that he would consider a halt to all offshore drilling, and told assembled reporters that the Department of the Interior had expanded the former buffer zone in the Santa Barbara Channel by an additional 34,000 acres. The previous buffer zone there would be converted into a permanent ecological preserve.

As Nixon and his entourage moved toward the parking lot, he said, “I think the Santa Barbara incident has frankly touched the conscience of the American people. We’re going to do better job in the future than we have in the past.”

On the day Nixon visited Santa Barbara, March 21, Hickel, in Washington, issued more stringent regulations for oil drilling and production off the coast of California. The new regulations included: use of more casing, additional safety testing, weekly training drills by oil platform crews, safety and antipollution devices required on all platforms, and scheduled and unscheduled inspections by the Geological Survey. “The program we are developing in response to the Santa Barbara tragedy,” Hickel said as he announced the new regs, “will serve as a model for our future actions along the nation’s entire coastline.”

A few days later, on March 26 Secretary Hickel announced that some offshore oil drilling in the Santa Barbara Channel would be resumed within days if the new standards set by the Department on March 21 were met. Hickel said the Department was studying each oil lease on a “lease-by-lease basis.” On April 1st, Hickel completed a preliminary assessment of the leases affected by the moratorium and allowed drilling to resume under stricter oversight on five of the seventy-two leases. Local residents were not happy.

1969: Sample of the protest art appearing in Santa Barbara, California at the time of the spill.

In an effort to ban all drilling in the Santa Barbara Channel the local group, Get Oil Out!, had sponsored a petition which had amassed some 110,000 signatures by May 1969. The petition was sent to Nixon shortly thereafter, its message to the president, stated in part as follows:

. . . With the seabed filled with fissures in this area, similar disastrous oil operation accidents may be expected. And with one of the largest faults centered in the channel waters, one sizeable earthquake could mean possible disaster for the entire channel area . .

Therefore, we the undersigned do call upon the state of California and the Federal Government to promote conservation by:

1. Taking immediate action to have present offshore oil operations cease and desist at once.

2. Issuing no further leases in the Santa Barbara Channel.

3. Having all oil platforms and rigs removed from this area at the earliest possible date.

Although the Nixon Administration and Hickel were making changes in offshore regulations and limiting some future production there, they did not, in the immediate months following the spill, limit leasing and production that had already begun or was in the process of being approved. In addition, a scientific panel Nixon had appointed to come up with recommendations, had more bad news for those in Santa Barbara who wanted an end to drilling.

DuBridge Report

In early February 1969, following the Union Oil blowout, Richard Nixon had appointed his science adviser, Dr. Lee DuBridge, to form an investigating committee to determine the proper course of action with regard to leasing and drilling in the Santa Barbara Channel. Nixon later amended this directive to also address what steps should be taken specifically regarding Union Oil’s operation there, as there had been some talk of abandoning that lease and removing the rig. The DuBridge Committee announced its recommendations on June 2, 1969 with a surprising declaration: The DuBridge Panel rec- ommended more drilling, not less. In order to control the oil pollution from the sea-bed fissures, more wells were recom- mended to drain the reservoir and relieve the pressure. more drilling should occur, not less. In order to control the oil seepage that was occurring from the Channel floor in the vicinity of the Union Oil operation – that is, to relieve the pressure in those underground reservoirs, according to the panel – more drilling was needed. Withdrawing the oil from structures under the platform “is a necessary part of any plan to stop the oil seep,” said the panel in its statement. “The situation which makes leaks possible,” DuBridge said, “is the fact there is oil down there. The only way to prevent future leaks is to get the oil out.”

Santa Barbara activists, meanwhile, were furious. They pointed to the fact that the panel only held two-days of hearings, with testimony from only government or oil industry representatives. The panel’s recommendations were issued on less than two pages. When citizens asked for the details, the Department of the Interior refused to make available the panel’s background data or Channel geological information used. Since it was based on industry data, it was proprietary and would not be released. On June 9, 1969, Interior authorized Union Oil to drill nine wells from Platforms A and B. These nine wells were drilled, completed, and, with one exception, were put into production during June and July 1969. Then came the Sun Oil project.

Sun Oil Platform

After a series of unsuccessful court battles in the summer 1969 to prevent further oil development in the Santa Barbara Channel, the Department of the Interior approved a plan by the Sun Oil Company to construct a new platform in the Channel – Platform Hillhouse – to be located about one mile east of Union’s Platform A. The go-ahead for that plan was given on August 15, 1969. Local activists, however, had vowed to stop the installation. Later that fall, as the drilling platform was being imported from its Oakland, California shipyard, and floated down the coast toward the Channel, the activists were nearby in their boats, reportedly harassing the convoy. At the platform site in the Santa Barbara Channel, protesters with Get Oil Out! (GOO) staged a “fish-in” in late November 1969 an attempt to stop the incoming rig. In fact, they refused to move until the Supreme Court responded to their appeal, which they soon lost. Then the crane lifting the rig from the barge began to have difficulty transferring Platform Hillhouse into position. In fact, it flopped over in the water, legs-up, not far from where the GOO protesters had set up their protest boats. Eventually, after some difficulty, Sun Oil’s Hillhouse Platform was installed correctly.

1969-1970: This photo of a boat being piloted by the Santa Barbara environmental group, Get Oil Out!, was taken by Los Angeles Times photographer Frank Q. Brown and was published on the front page of the January 29 1970 Los Angeles Times. The group at the time, on the first anniversary of the spill, was dropping a buoy in the Santa Barbara Channel to mark the area where the spill first occurred. Get Oil Out! had also sponsored an August 1969 fleet of protest boats to stage a “fish-in” in a failed attempt to block the installation of a Sun Oil drilling platform.

On Jan. 20, 1970, Hickel rejected a request made by Get Oil Out! to suspend oil drilling in the channel to see if it would stop the seepage. The Department of the Interior, in refusing, again pointed to the recommendations of the DuBridge Panel, that pumping the underwater field dry was the only way to guarantee that leaks would not recur. Santa Barbara activists, however, persisted in their effort to challenge oil development in their community.

On January 28, 1970, on the first anniversary of the Santa Barbara oil spill, a sizable group of protesters, numbered at about 500 began moving toward the Santa Barbara municipal pier, also used to service offshore oil operations. City police, reinforced by sheriff’s deputies and highway patrolmen, initially delayed the demonstrators from moving onto the pier. There were a few brief scuffles but no arrests or injuries. And later, about 150 of the demonstrators were allowed to march onto the pier by the wharf operator. There, they started what they claimed would be an all-night sit-in. But after about 17 hours, the demonstrators dispersed after being threatened with tear gas and arrest by the police.

January 29th, 1970: Police move in behind protesters blocking the entrance to the Santa Barbara municipal pier on the first anniversary of the Santa Barbara oil spill. This photo was published in the January 30th, 1970, Los Angeles Times. Photo, Bruce Cox / Los Angeles Times.

National Politics

Although the activists in Santa Barbara may not have been successful in halting oil development in the Santa Barbara Channel in the immediate aftermath of the Union Oil blowout in 1969-1970, the larger environmental movement and policy changes touched off by the Santa Barbara spill left an enduring legacy. The Santa Barbara spill – with its photographic and televised imagery – gave visceral force to the larger “environmental crisis” then apparent across much of the nation. A receptive audience, already aware of Rachel’s Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962 and the Torrey Canyon tanker disaster of 1967, and further angered by the Cuyahoga River fire of June 1969, was ready for action. By the time of the first Earth Day of April 22, 1970, with thousands of demonstrations and millions of participants, a nationwide groundswell on behalf of environmental protection was clear. Congress and the White House – soon engaging in a bit of competitive politics on the issue – moved quickly to adopt new laws. In fact, looking back on that time, it was truly astonishing how much environmental protection law came on line in just a few short years, especially between 1969 and 1972.

Senator Ed Muskie (D-ME). |

Senator Henry Jackson (D-WA). |

By mid-year 1969, Congress and the Nixon White House were pushing and/or debating a number of new environmental measures. In Congress, bills on air and water pollution, land use, wilderness protection, national environmental policy and more were introduced by Republican and Democrat alike – some of the latter potential rivals to Nixon for the presidency in 1972. In fact, a noted leader on pollution legislation at the time, Senator Ed Muskie, the Democrat’s VP candidate in 1968, was a favorite for the party’s presidential nomination in 1972. Muskie already had major bills pending in the Senate on air and water pollution. Other members, including Senator Henry Jackson (D-WA), also a potential Democratic presidential candidate, would emerge as a leader on environmental legislation. In February 1969, Jackson introduced S.1075, the measure that would become the National Environmental Policy Act.

Richard Nixon, a president more interested in foreign policy than domestic matters, and not generally inclined to environmental protection, nonetheless became the president of record who signed a number of environmental laws in the early 1970s. He was also eyeing his potential Democratic rivals for president in 1972, which spurred Nixon’s “interest” in the environment.

January 22nd, 1970: President Richard Nixon’s “State of the Union” speech, stressing “battle to save the environment,” garners front-page headline in the New York Times.

That law put in place an important environmental review process for assessing the potential environmental impacts of all major federal actions and public works projects — reviews that required a detailed “environmental impact statement” (EIS) on the project with public hearings and comment period. NEPA also established the President’s Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ).

Meanwhile, Nixon, swept along by the rising environmental tide, would also use his State of the Union address of late January 1970 to demonstrate his proposed commitments for environmental protection. In reporting on Nixon’s address, the New York Times gave it the headline, “ Nixon, Stressing Quality of Life, Asks in State of Union Message For Battle to Save Environment.” The following month, Nixon would also send a special message to the Congress outlining his environment programs, in which he would say, in part: “Our current environmental situation calls for fundamentally new philosophies of land, air, and water use, for stricter regulation, for expanded government action, for greater citizen involvement, and for new programs.”

Official logo, U.S. EPA.

In February 1971, in submitting his “Special Message to the Congress Proposing the 1971 Environmental Program” – one of a series of environmental messages he sent to Congress during the years of his presidency – Nixon invoked a famous literary work at one point saying: “In his tragedy, ‘Murder in the Cathedral,’ T. S. Eliot wrote, ‘Clear the air! Clean the sky! Wash the wind!’ I have proposed to the Congress a sweeping and comprehensive program to do just that, and more–to end the plunder of America’s natural heritage… With your support, and with the help of the Congress, we can reclaim and preserve the natural beauty of America unto all the generations that come after us.”

|

“Wally Hickel”  October 1969: U.S. Interior Secretary, Walter Hickel, shown at press conference as filmed by KPIX-TV Eyewitness News, San Francisco, CA. The eldest of nine children, Wally Hickel had grown up in Kansas, where he became a scrappy boxer, winning some championship bouts. Later, as a construction worker who became a successful businessman and politician, he would rise to play a role influencing the Republican Party to support Alaskan statehood in 1958. As that state’s second governor, he presided over the discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay, yet was a moderate on its development. When it came to dealing with the Santa Barbara oil spill, after being in office as Secretary of the Interior for only a few days, he surprised his critics by moving quickly to tighten offshore oil regulations. He placed unlimited liability on an offshore operators to clean up any oil spill and bear the full cost, whether the operator’s fault or not. He also authorized Interior officials to shut down any operation polluting or threatening to pollute the ocean from a federal lease—with a verbal order, if necessary. But with the Santa Barbara blowout, Hickel apparently faced some White House pressures to “downplay” the spill, as he would later explain in a May 2008 interview with Timothy Naftali at the Nixon Library in California: Timothy Naftali:…What do you remember of the oil spill off of Santa Barbara? Walter Hickel: Well, we had to get the government involved in that. …I didn’t realize how massive an oil spill that was until I went out there and took a look. My God, that was a disaster. But they were trying to cover it up, cover it up, cover it up. I said, “Face it, we’re going to clean this thing up.” And it was a battle, even with the White House. Timothy Naftali: With the White House? Tell us about that. Walter Hickel: Well, they didn’t want to…make it look like too big an event, you know, and I said, “Just tell the truth about that. That’s the biggest disaster I’ve ever seen happen by the private sector.” And that oil was just …all over that place. … Oh boy, that was a disaster… Yet there really could be no downplaying of that spill, as the media – and Nixon’s competitors in Congress – were all over it. So, as Hickel stated, they had to face up to it, which they did. Still, that the White House intention was there initially to try to minimize the spill is consistent with other Nixon Administration behavior. In addition to the Santa Barbara spill, Hickel would also face two other offshore disasters – blowouts and infernos in the Gulf of Mexico – one at a Shell rig and another at a Chevron rig. But in these cases, too, Hickel did not go easy on the oil companies. In the Chevron case, he pushed the Justice Department to file a lawsuit charging 900 violations of the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act of 1953. Hickel was active in other environmental areas as well, filing lawsuits against 10 companies accused of discharging mercury into interstate waters. He was also involved in helping stop a giant jetport slated for the Florida Everglades.  1969: U.S. Interior Secretary, Walter Hickel, as filmed by KPIX-TV Eyewitness News, San Francisco, at press conference, October 1962. Click for 2 minute clip. “I believe this administration finds itself today embracing a philosophy which appears to lack appropriate concern for the attitude of a great mass of Americans – our young people,” Hickel wrote, in part. That letter garnered worldwide media attention, and on November 25, 1970, Hickel was fired. He would again become Governor of Alaska in 1990-94 and would figure in other oil and political controversies in that state. Walter J. Hickel died of natural causes in May 2010. He was 90 years old. |

By late October 1972 additional environmental laws were adopted, among them: the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972; the Marine Mammal Protection Act; the Federal Environmental Pesticide Control Act (amending the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act); the “Ocean Dumping Act,” formally titled the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act, for regulating ocean dumping and creating marine sanctuaries; and the Coastal Zone Management Act, for land use planning and resource protection within the coastal zone.

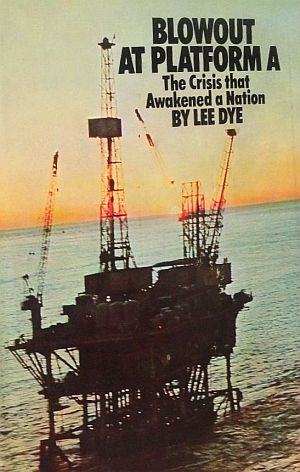

Lee Dye's 1971 book, "Blowout at Platform A: The Crisis That Awakened a Nation" (Doubleday). Click for copy.

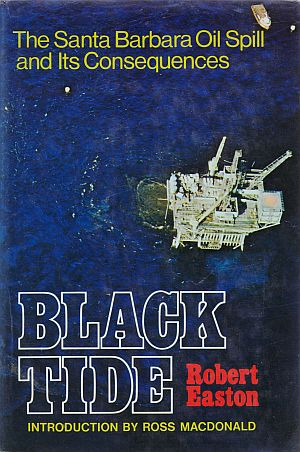

Among books that appeared in the years immediately following the spill were these two (covers shown here at right and below): Lee Dye’s Blowout At Platform A: The Crisis That Awakened a Nation (Doubleday, 1971); and Robert Easton’s Black Tide: The Santa Barbara Oil Spill and Its Consequences (Delacorte, 1972).

Spill Post-Mortem

Investigations of the Santa Barbara blowout would later reveal that the spill was preventable. Union Oil had obtained approval of the U.S. Geological Survey to use a shorter length of casing pipe. Though federal standards at the time required well bores to be outfitted with well casing – a steel lining that helps prevent blowouts to at least 300 feet below the ocean floor – Union Oil was given a waiver that allowed it to install casing that was 61 feet shorter. As the drilling proceeded into a highly pressurized zone of oil and gas, it caused an explosion so powerful that it cracked the ocean floor in five places and prompted the mass spill. Drilling muds used reportedly fell below safety margins as well. But in the wake of the spill, offshore drilling regs were tightened for all federal offshore oil and gas leasing.

By the late summer 1969, the Department of Interior issued completely new regulations for all Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) leasing and operations – the first update since the program’s start fifteen years earlier. The regulations tightened safety rules and other precautions to prevent future blowouts and oil pollution from offshore rigs; gave the U.S. Geological Survey greater access to drilling logs and other information; and generally required a much greater consideration of environmental effects than previously. These were the first rules under which the Department could prohibit leasing in areas of the continental shelf where environmental risks were too high. Although a small amount of drilling continued off the coast of California, the Santa Barbara accident furthered an existing trend of almost exclusive reliance on the Gulf of Mexico for U.S. offshore oil production.

Robert Easton's 1972 book, “Black Tide: The Santa Barbara Oil Spill and Its Consequences,” (Delacorte). Click for copy.

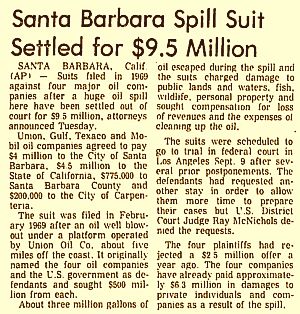

Economic losses resulting from the spill were difficult to estimate, but some figures did become available. In 1969, the tourist industry suffered considerably, but did recover in subsequent years. A class-action lawsuit awarded nearly $6.5 million to owners of beachfront homes, apartments, hotels, and motels. Commercial and recreational boat owners and nautical suppliers were awarded $1.3 million for property damage and loss of revenue. Commercial fishers lost access to some fisheries temporarily. Union Oil also settled a lawsuit filed by the State of California, County of Santa Barbara, and the towns of Santa Barbara and Carpinteria in the amount of $9.5 million for loss of property.

Change Came…

Still, in the years following the Santa Barbara oil spill of 1969, as state and federal authorities put into practice environmental protection policies, a new kind of “environmental due process” began to take hold. Major projects and decision making by government and business that could affect the environment were now dealt with differently. Impacts and possible alternatives were weighed and considered before approvals could be given – with decisions made after public hearings and comment. The Santa Barbara Channel wasn’t the immediate beneficiary of these fundamental changes in environmental consideration. Indeed, more drilling rigs went in. In the years following the Santa Barbara oil spill, as the new laws kicked in, an “environmental due proc- ess” began to take hold… In Santa Barbara and elsewhere, it took time for the machinery of “environmental due process” to begin working. But gradually it did take hold – and it was a major change in thinking and foresight. New leases and/or drilling rig proposals had to be evaluated for their total environmental impact and some could be prohibited. Highway builders could no longer level urban communities for a freeway; untreated sewage or chemicals could not longer be discharged into rivers and streams; automakers had to equip cars with catalytic converters to clean up smog-causing exhausts; more wilderness areas, marine mammals, and wildlife were given protection. The environment was accorded new “standing,” both in the legal and lay sense of that term; it was no longer a “free” medium for polluters or exploiters; it was given a higher value and put on a more even footing with purely economic decisions and/or government dictums. In a few places, environmental values and environmental protection would work their way into the earliest R&D stages of product development – but certainly not everywhere.

…More Needed

Environmental protection needed then, and still needs today, to be at the earliest stages of resource development, product invention, and capital goods planning. Yet sadly, to this day, there are too many products, projects, and technologies that do not have – or have never had – before-the-fact environmental protection and/or life-cycle analysis built into them. The pollution legacies of the chemical, auto, and oil industries, to name but three – and the spills, fires, emissions, toxic wastes, and other public dangers that flow from them daily – provide ample testament that environmental protection has not been deeply internalized into much of today’s economic activity. The policy advances, true, have made major differences in some cases. Yet regulators tend to play catch-up and much environmental law seems palliative rather than curative. On balance, the damage continues. All the more reason why the fights that began in 1969 and 1970 at Santa Barbara and elsewhere that helped spawn a popular rise in environmental awareness and activism need to continue today with even greater resolve.

See also at this website, for example: “Deepwater Horizon, Film & Spill,” a story about the making of the 2016 Hollywood film on the BP offshore oil rig disaster, plus a recap of the politics, media and corporate maneuvering during the real BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico; and, “Environmental History,” a topics page with links to additional stories covering environmental issues. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 22 February 2016

Last Update: 21 April 2021

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Santa Barbara Oil Spill: California, 1969,”

PopHistoryDig.com, February 22, 2016.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

1969: Close up of Union Oil rig and the roiling surface waters from escaping oil & gas on the sea-bed below. |

Feb 11th, 1969: Part of the daily coverage the Los Angeles Times newspaper ran during the Santa Barbara oil spill. |

1969: Aerial photo of Union Oil rig after the blowout. Eventually, an 800-square-mile slick formed. |

Feb 6th, 1969: The Telegram-Tribune of San Luis Obispo reporting on the "miles of black ooze" that hit the beaches. |

1969: Associated Press photo of workers raking up straw used to absorb some of the crude oil that came ashore from the Union Oil blowout. |

1969: Life magazine photo of workers steam-cleaning oil stained rocks at Carpinteria, CA. |

1969: Volunteers working to save oiled sea bird following Santa Barbara spill. Telegram-Tribune, San Luis Obispo. |

1969: Life magazine photo of oil-splotched sea lion and cub on San Miguel Island off coast. Photo, Harry Benson. |

Feb 7, 1969: Sample of newspaper headlines used across the country during the Santa Barbara oil spill-- this one from the La Crosse Tribune in Wisconsin. |

1969: Santa Barbara citizen displays his "dead sea" placard during oil spill protest gathering. |

Various lawsuits were filed over the Santa Barbara spill in 1969, but most were not settled until several years later. This Associated Press story of July 1974 reports on one of those outcomes. |

1969: Early attempts to corral the Santa Barbara oil spill using boats and oil booms. |

1969: Santa Barbara clean-up crews “pitchforking” oil-soaked hay from corralled oil spill in harbor area. Photo, Bob Duncan. |

1969: Bulldozers formed piles of oil-soaked sand and cleanup wastes on the beaches in Santa Barbara that were hauled away to landfills by large trucks. |

1969: During oil spill cleanup in Montecito, a worker appears to be trying to retrieve something mired in the muck, possibly an oiled bird. |

1969: Life magazine photo of oil-stained boulders with oil rig on the far horizon. Boulders located at Santa Claus, south of Santa Barbara. Photo, Harry Benson. |

“An Oil ‘Tide’” (photograph), Los Angeles Times, January 30, 1969, p. B-1.

Eric Malnic, “Sea Birds Killed by Oil Slick; Fight to Seal Well Leak Speeded,” Los Angeles Times, February 1, 1969, p. 1.

“Oil Slick Spreads, But Leak Slows,” New York Times, February 1, 1969, p. 32.

“Seabirds Killed by Oil,” Washington Post, February 1, 1969, p. A-6.

Harry Trimborn, “Battle Shaping Up Over Offshore Oil,” Los Angeles Times, February 2, 1969, p. 1.

Gladwin Hill, “Slick Off California Coast Revives Oil Deal Disputes,” New York Times, February. 2, 1969, p. 1

Darren Hardy, “1969 Santa Barbara Oil Spill”, UCSB.edu (includes Dick Smith photo collection, UCSB, 1969-1971).

Spencer Rich, “Oil Industry To Give Its Endorsement to Legislation on Offshore Pollution,” Washington Post, February 1969.

Robert Rawitch, Lee Dye, “Hickel Flies to Santa Barbara to Examine Offshore Oil Leak,” Los Angeles Times, February 3, 1969, pp. A1-A2.

Charles Hillinger, Dial Torgerson, “Hickel Shuts Down Drilling Operations,” Los Angeles Times, February 4, 1969, p. A1-A2.

“Santa Barbara Oil Spill,” Consortium Library.org.

“1969 Santa Barbara Oil Spill,” Wikipedia .org.

Dick Main, Dial Torgerson, “Shifting Winds Push Oil Slick Onto Santa Barbara’s Beaches,” Los Angeles Times, February 5, 1969, pp. A1-A2 .

UPI, “Pacific Oil Slick Nearer To Coast,” Lodi News-Sentinel (Lodi, California), February 5, 1969, p. 1.

“Scum Mired Birds Dying By The Hundreds,” Los Angeles Times, February 6, 1969, p. 1.

Dial Torgerson and Leonard Greenwood, “Oil Slick Damage, Bird Deaths Soar,” Los Angeles Times, February 6, 1969, p. A1-A2.

Dial Torgerson and Leonard Greenwood, “Drifting Oil Smears Beaches for 12 Miles; Scum-Mired Birds Dying by Hundreds,” Los Angeles Times, February 6, 1969, pp. 1, 3.

Warren Weaver Jr., “Senate Hearing Held,” New York Times, February 6, 1969, p. 19.

“Oil Firm Official Defends Drilling at Senate Hearing,” Los Angeles Times, February 6, 1969, p. 1.

Spencer Rich, “Hickel Assailed On Oil Policies; Hickel Scored For Not Halting Coast Oil Drills; Called ‘Tokenism;’ None in Union Parcel,” Washington Post, Times Herald, February 6, 1969, p, A-1.

Edward Weinberg, Solicitor, U.S. Department of the Interior, Memo, “Circumstances Under Which Drilling in the Santa Barbara Channel May Be Suspended,” February 1969, 2pp.

Warren Weaver, Jr., “President May Call G.I.’s To Combat Coast Oil Slick; Nixon May Use G.I.’s to Fight Oil Slick,” New York Times, February 7, 1969.

UPI, “Oil Slick Heading For L.A. Harbor; Offshore Well Still Spewing Tons of Crude,” The Desert Sun (Palm Springs, CA), February 7, 1969, p, 1.

Spencer Rich, “Stringent Rules for Drilling Promised,; Stringent Drilling Rules Pledged; No New Operations; Defends Decision…,” Washington Post, Times Herald, February 7, 1969, pp. A1-A2.

Leonard Greenwood and Eric Malnic, “Oil Seepage May Be Under Control,” Los Angeles Times, February 8, 1969, p. 1.

Spencer Rich and George Lardner, “Hickel Shuts Down Oil Operations in Leak Area,” Washington Post, Times Herald, February 8, 1969, p. 1.

George Lardner, “U.S. Waived Deeper Casing For Well Causing Oil Slick…,” Washington Post, Times Herald, February 8, 1969, p. A-1.

Harry Trimborn and Leonard Greenwood, “Oil Flow Plugged; Big Cleanup Starts,” Los Angeles Times, February 9, 1969, p. 1.

Bob Rose, “It Ruins Beaches, Smothers Lives,” Boston Globe, February 9, 1969, p. 13.

“Huge Channel Oil Spill Blows Up Storm,” Oil & Gas Journal, February 10, 1969.

George Lardner Jr., “Oil Flow Capped but Controversy Isn’t,” Washington Post, Times Herald, February 10, 1969, p. A-12.

Richard Nixon: “Statement on Coastal Oil Pollution at Santa Barbara, California.,” February 11, 1969, via Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, USSB.edu.

“Oil Slick Breaks Up, Soaks Beaches,” Washington Post, Times Herald, February 11, 1969, p. A-7.

Charles T. Powers, “Uneventful Day: Then Well No. 5 Blew Out,” Los Angeles Times, February 11, 1969, p. 1

Dial Torgerson, “New Shoreward Surge of Oil Feared as Storm Nears Area,” Los Angeles Times, February 12, 1969, p. A3-A4.

“Bird Cleaning,” photograph, Washington Post, Times Herald, February 12, 1969, p. A-7.

“Befouled Grebe Gets a Bath,” photograph, Time, February 14, 1969, p. 25.

“A California Oil Strike Nobody Wanted,” Life, February 14, 1969, pp. 30–31.

“The Great Blob,” Newsweek, February 17, 1969, pp. 31–32.

Robert L. Jackson, “Oil Firms Shielded in Spillage Cases, Senate Aides Say,” Los Angeles Times, February 17, 1969, p. A-1

Dial Torgerson, “Crews Try to Cut Gas Pressure on Oil Leak,” Los Angeles Times, February 18, 1969, p. 3.

Spencer Rich, “Oil Firms Made Liable For Pollution Damages,” Washington Post, Times Herald, February 18, 1969, p. A-1.

Dial Torgerson, “State Starts Action to Obtain $1 Billion in Oil Leak Damage,” Los Angeles Times, February 19, 1969, pp. 3-4.

“The Environment: The Dead Channel,” Time, February 21, 1969.

Lee Dye, “More Oil Ashore; Film Appears Thicker Than First Spillage,” Los Angeles Times, February 27, 1969, p. 1.

UPI, “Congress Urged By Interior Secretary to Toughen Oil Pollution Liability Bill,” The Bulletin (Bend, Oregon), February 28, 1969, p. 5.

UPI, “Hickel Wants More Punch In Oil Bill,” Sarasota Journal (Florida), February 28, 1969.

Spencer Rich, “Hickel Endorses Stricter Oil, Water Controls,” Washington Post, Times Herald, March 1, 1969, pp. A1-A2.

“Udall Admits ‘Overconfidence’ in Granting Ocean Oil Leases,” Los Angeles Times, March 11, 1969, p. A-3.

Spencer Rich, “Udall: Oil Decision a ‘Bay of Pigs’,” Washington Post, Times Herald, March 11, 1969, p. A-4.

Spencer Rich, “Sanctuary Set at Calif. Oil Drilling Site,” Washington Post, Times Herald, March 12, 1969, p. A-4.

AP, “Nixon On Oiled Beach;.Little Of Vast Slick Remains,” Toledo Blade (Toledo, Ohio), March 22, 1969, p. 1.

Press Conference Re: “New Oil Regulations for Offshore Drilling and Production at Santa Barbara, California”, the Honorable Walter Hickel, Secretary, Department of the Interior, Room 1324, Longworth House Office Building, Washington, D.C., Friday, March 21, 1969, 32pp.

Associated Press, “Hickel Issues Oil Rules…For California Coast,” The Daily Illini (Urbana Illinois), March 22, 1969, p. 9.

Jerry Ruhlow, “Sea Life Refuges on Coast Affected by Deluge of Oil,” Los Angeles Times, March 31, 1969, p. D1-D2.

Charles T. Powers, “Ban on Offshore Wells Sought by Santa Barbara,” Los Angeles Times, April 3, 1969, pp. 3-4.

“Santa Barbara County Files Oil Drilling Suit,” Los Angeles Times, April 5, 1969, p. A-13.

John H Averill, “White House Opposes Channel Oil Well Ban,” Los Angeles Times, May 20, 1969, p. 3.

Don Kirkman, “2 Senators Rap Go Ahead on Oil Wells: Muskie, Cranston Assail Report as Unscientific,” The Pittsburgh Press, June 6, 1969.

David Snell, “Iridescent Gift of Death; As the Oil Spill off Santa Barbara Keeps Right on Killing, The Proposal is For All-Out Drilling,” Life (photographs by Harry Benson), June 13, 1969, pp. 22-27.

Spencer Rich, “Hill Action Due On Oil Leaks; Liability of Ships Imposed by Hickel; Local Groups Displeased,” Washington Post, Times Herald, June 23, 1969, p. A-2.

William M. Blair, “Offshore Oil Pacts Face New Hurdles; Offshore Oil Leases Facing New Curbs, With Role for Public in Decisions,” New York Times, June 26, 1969.

Morton Mintz, “Oil Spill ‘Radicalizes’ Staid Coast City,” Washington Post, Times Herald, June 29, 1969, pp. 47-48.

U.S. Department of the Interior / Federal Water Pollution Control Administration, Review of Santa Barbara Channel Oil Pollution Incident (by Battelle Northwest, Richland Washington), July 18, 1969.

Dennis M. O’Connell, “Continental Shelf Oil Disasters; Challenge to International Pollution Control,” 55 Cornell Law Review, 113 (1969).

Associated Press, “Santa Barbara Is Still Boiling Over Oil Well,” Reading Eagle (Reading, PA), November 23, 1969.

“Walter Hickel on the Santa Barbara Channel Oil Spill,” News Conference, KPIX-TV Eyewitness News Report (video), October 1969, via San Francisco Bay Area Television Archive.

Ross MacDonald and Robert Easton, “Thou Shalt Not Abuse the Earth,” New York Times Magazine, October 12, 1969, p. 32 (MacDonald and Easton were then co-founders of the Santa Barbara Citizens for Environmental Defense).

“Floating Rig Sinks; Nixon Asked To Halt Coastal Drilling,”Toledo Blade (Toledo, OH), November 23, 1969, p. 9.

Harvey Molotch (University of California, Santa Barbara), “Oil in Santa Barbara and Power in America,” Sociological Inquiry, 40 (Winter), 1969, pp. 131-144.

“Oil Leases,” CQ Almanac 1969, 25th ed., Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, 1970, p. 522.

Bob Duncan, Photo Gallery, “Santa Barbara Oil Spill, 1969,” Flickr.com.

W. Gerber, “Coastal Conservation,” CQ Researcher (Editorial Research Reports), February 25, 1970, Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly/CQ Press.

“Nixon Urged To Bar New Oil Platform,” Washington Post, Times Herald, January 2, 1970, p. A-3.

Gladwin Hill, “One Year Later, Impact of Great Oil Slick Is Still Felt,” New York Times, January 25, 1970.

“Nixon Seeks Oil Spill Area As Sanctuary; Nixon Would Void Oil Leases Off Santa Barbara,” Washington Post, Times Herald, June 12, 1970, p. A-1.

“Environment: Good News for Santa Barbara,” Time, June 22, 1970.

Philip D. Carter, “Stringent Oil Spill Rules Set; Stringent New Oil Spill Regulations Are Issued by Interior Department,” Washington Post, Times Herald, July 25, 1970, p. A-1.

Lee Dye, Blowout at Platform A: The Crisis That Awakened a Nation, New York: Doubleday, 1971, 231 pp.

New York Times News Service, “Interior Asks Resumption Of Santa Barbara Oil,” St. Petersburg Times (Florida), September 3, 1971, p. 4-A.

L.A. Times News Service, “2 More Oil Platforms Given Nod “[‘Platform C’ and ‘Henry’], Sarasota Herald-Tribune (Sarasota, Florida) September 3, 1971.

Robert Easton, Black Tide: The Santa Barbara Oil Spill and its Consequences, New York, NY: Delacorte Press, 1972.

Carol and John Steinhart, Walter Hickel (Foreword), Blowout: A Case Study of the Santa Barbara Oil Spill, Duxbury/ Wadsworth, Belmont, California, 1972, 138 pp.

John C. Whitaker (Nixon’s Cabinet Secretary in 1969, and associate director of the White House Domestic Council for environment, energy, and natural resources policy, 1969-1972), “Earth Day Recollections: What It Was Like When The Movement Took Off,” EPA Journal, July/August 1988.

President Richard M. Nixon, “Special Message to the Congress Outlining the 1972 Environmental Program,” February 8, 1972.

A. E. Keir Nash, Dean E. Mann, Phil G. Olsen, Oil Pollution and the Public Interest: A Study of the Santa Barbara Oil Spill, Institute of Governmental Studies, University of California, Berkeley, October 1972, 136pp.

Nancy I. Nicholson, University of Southern California, “The Santa Barbara Oil Spills in Perspective,” California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations, Reports Volume XVI, 1972, pp. 130-149.

James Rathelsberger (ed.), Nixon and The Environment: The Politics of Devastation, Village Voice, 1972.

Nick Welsh, “The Big Spill,” Santa Barbara News-Press, January 26, 1989.

Miles Corwin, “1969 Santa Barbara Oil Spill,” Los Angeles Times, January 28, 1989.

Keith C. Clarke and Jeffrey J. Hemphill, “The Santa Barbara Oil Spill, A Retrospective,” in Darrick Danta (ed.), Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers, University of Hawaii Press, 2002, vol. 64, pp. 157-162.

“Interview with Walter J. Hickel,” Center of The American West, Boulder, Colorado, October 15, 2003.

dsteffen, “How Regulation Came to Be: Santa Barbara,” DailyKos.com, Sunday Jan 24, 2010.

Sarah Gardner, “Reporter’s Notebook: Lessons from the Santa Barbara Oil Spill,” Marketplace.org, June 25, 2010 (with photos).

Rob Reynolds, “Santa Barbara: The Spill That Energized a Movement,” CommonDreams .org, June 7, 2010.

Associated Press, “Gulf Spill Lacks Transformational Punch of 1969 Santa Barbara Oil Spill,” FoxNews.com, July 29, 2010.

Cindy Wu, “The Santa Barbara Disaster of 1969: A Turning Point for American Environmentalism.”

Matt Dozier, National Marine Sanctuaries’ Office of Response and Restoration, NOAA, “National Marine Sanctuaries: How a Disaster Changed the Face of Ocean Conservation,” October 26, 2012.

Erwin Mauricio Escobar, “Nixon and the Environment: Clean Air, Automobiles and Reelection,” A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, Florida, May 2013.

“January 28, 1969: An Ecological Disaster and Impetus For a New Ethos,” Friends of Cal Archives.org, January 28, 2014.

“45 Years After the Santa Barbara Oil Spill, Looking at a Historic Disaster Through Technology,” National Marine Sanctuaries’ Office of Response and Restoration, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce, January 28, 2014.

Alan Neuhauser, “Oil Spills Aplenty Since Exxon Valdez; Storms, Ship Collisions, Pipeline Ruptures and Explosions Have Spilled Millions of Gallons of Oil Across the United States,” U.S. News, March 25, 2014.

Ari Phillips, “How A Massive Oil Spill in 1969 Changed Everything,” ThinkProgress.org, June 30, 2014.

Christine Mai-Duc, “The 1969 Santa Barbara Oil Spill That Changed Oil and Gas Exploration Forever,” Los Angeles Times, May 20, 2015.

Francie Diep, “What Can the 1969 Santa Barbara Oil Spill Teach Us About Animal Life? History — and Science—have a Lot to Teach Us Here in Santa Barbara, California,” Pacific Standard, May 26, 2015.

“Santa Barbara Oil Spill: From 1969 to 2015,” EdHat.com (Santa Barbara, CA), May 23, 2015.

Staff Working Paper No. 11, “A Brief History of Offshore Oil Drilling” (draft), National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling, no date, 18pp.

________________________________________________________