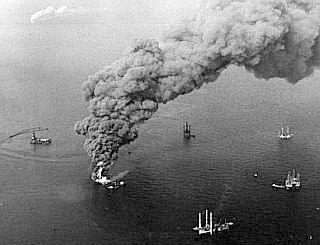

December 1970: Smoke & flames rise from Shell Oil's burning rig in the Gulf of Mexico, as five mobile rigs around it work to drill relief wells. Photo: Times-Picayune, New Orleans.

[ Note: In October 2011, following the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, the U.S. Minerals Management Service (MMS) was dissolved and divided into three new agencies to separate potential conflicts of interest: the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, for regulation and accident reports; the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management for leasing; and the Office of Natural Resources Revenue for revenue collection.]

The BP disaster of 2010 was certainly the most notable of U.S offshore incidents in recent history. Yet spills and blowouts have been occurring in the offshore regions for decades. And these incidents are but one part of the continuing environmental damage that has occurred at the hand of the fossil fuels industry for more than a century. Herewith, the case of Shell Oil’s “platform 26” in 1970.

Headline from ‘Washington Post/Times Herald’ story of Dec. 7th, 1970, reporting on Shell Oil’s offshore rig blowout & fire.

On December 1st, 1970, an offshore oil rig operated by the Shell Oil Company in the Gulf of Mexico in Bay Marchand near Port Fourchon exploded and caught fire. Four workers were killed and 37 others were seriously burned, some injured when jumping from the burning rig into the water to save their lives. A well blowout was later determined to be the cause.

The Shell platform and several of its multiple wells burned for nearly three months. A large oil slick also formed, covering more than twenty miles at one point, stretching into the Gulf and oiling some Louisiana islands and beaches. Oil slicks of smaller size, breaking up over time, were still visible in the Gulf five months after the incident – through April 1971. At the time, the Shell blowout and fire was the worst offshore oil disaster to have occurred in the Gulf of Mexico. The incident lasted 137 days with some of its oil reaching Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

December 1970: Shell”s “Platform 26” burning in the Gulf of Mexico following well blow out. Photo by Bob King aboard Coast Guard cutter, ‘Dependable,’ arriving at scene. |

December 1970: Shell offshore oil rig blaze in the Gulf of Mexico. Photo, Bob King, aboard ‘Dependable’. |

December 1970: Bob King photo of Shell offshore platform blaze captures the beginning collapse of the rig. |

December 1970: Shell offshore oil rig in collapsed state, being sprayed with water as fire continues. Photo, Bob King, from Coast Guard cutter, ‘Dependable’. |

Incident History

Also known as “Platform 26,” or the “Baker” drilling rig, the Shell offshore platform included 22 production wells, which before the blowout were producing 17,500 barrels of oil and 40 million cubic feet of natural gas each day. One of the wells – the 21-B well with a yield of more than 400 barrels a day – had ruptured about 12 feet above the water line and became a primary feeder of the fire. The flames from the burning platform leapt 400 feet into the air. Burning oil covered the surface of the water in an irregular 50-foot circle around the platform. For the first two-to-three days, the fire raged at full throttle.

One sequence of photos taken by Bob King, then stationed aboard the Coast Guard cutter, Dependable, is shown at right. King witnessed the early days of the inferno and captured the blaze, some of the firefighting, and the rig’s collapse. “The purpose of our assignment,” King has recalled recently, “–which was two weeks out and 2 in — was for search and rescue and recovery, and also pollution control. Unfortunately we had to recover two men that lost their lives.”

J.J. Cadigan, commander of the Dependable, after arriving on the scene, reported the following: “Six wells appear to be burning, including one gas well… Oil is spilling on the water and burning. In addition, two to three wells are spewing downward [and] flaming downward.” Cadigan also offered that there appeared to be no significant pollution problem, as “the oil escaping from the flow lines is burning on the water, extending about 50 feet from the platform.” Yet there would be continued oil pollution in the Gulf and on some beaches from the disaster for weeks after.

By December 3rd, 1970 the big service crane on the rig collapsed towards the center of the platform at a 60° angle.

Meanwhile, in an effort to cut off the oil supply feeding the blaze from the bad wells, several drilling rigs were deployed to drill relief wells around the troubled Shell rig. The first of the relief wells, started on December 5th, would eventually reduce some of the oil flow. However, oil slicks that formed near the platform ignited periodically, endangering and hindering the response teams.

Six days into the incident, on December 7th, well 21-B was still contributing its yield to the fire. At least eight other wells at the rig were also burning. Shifting winds, fog, and rough seas slowed the efforts underway to fight the blaze and control the spillage.

Two firefighting firms, Jet Barges Jaraffe and Red Adair, were pumping about 19 million gallons of water per day to cool the burning platform. By December 30th, salt water was pumped into the relief well to help kill 21-B, the well with the largest fire. Killing this well reduced the intensity of the fire by about 40 percent.

Chemical dispersants were used early in the response to prevent oil slicks from developing. The dispersant concentration was not allowed to exceed 0.03 percent of the total spray stream, due to its toxic nature. Aerial application of the dispersant was also used along the shoreline from the west end of east Timbalier Island to 1.5 miles west of Belle Pass.

Skimmers, straw, and booms were used to contain and collect oil when possible. Shell’s Oil Herder product was used to aid skimming operations two miles southwest of Belle Pass.

An oil slick entered Timbalier Bay by late December, and some of it reached the beach. A week later, pollution surveys reported scattered oil accumulations on the beach, and some at the southern end of Grand Isle. Oil accumulations were also noted southwest of Caminada Pass.

On January 13th, oil along Grand Isle Beach was reported to be breaking up into globs and patches with the incoming tide. Still, a 1.5-inch thick accumulation of oil was observed near the Grand Isle Beach jetty. A slick ten feet wide and 6-to-12 inches thick floated on the water. Vacuum trucks later recovered oil from Grand Isle Beach and truckloads of litter and oil emulsion were picked up and hauled away by January 15th.

Still Burning

By January 20th, 1971, nearly two months later, eight of the wells at the damaged platform remained on fire. Workers had put through a relief well by this time attempting to contain the flow from the blowout, but the fire and oil flow continued. By January 20th, the slick extended two miles southwest of the fire, producing a fan of rainbow sheen for another six miles.By January 20, 1971, nearly two months after the explosion, eight of the rig’s wells were still burning and the oil slick extended two miles from the fire. Streaks of sheen extended for up to 29 miles southwest of the platform, with a maximum width of four miles. Well-head piping was severely damaged by the intense heat of the fire. Shell Oil Co. personnel constructed an abrasive cutting boom in an attempt to cut the damaged well head off the B-8 well, which was bent into the water and partially submerged, causing a pollution problem. This device was used to cut the well heads off two of the wells and a sand-blast cutting device was used to cut the piping off two other wells. Three additional well heads were cut by February 11th. Oil spill response operations began moderating on March 1, 1971, as a U.S. Coast Guard cutter and helicopter were released from the scene by then. Still, relief drilling, capping, and pumping of the wells continued throughout April. The next-to-last well fire to be quelled – number 10 of the burning wells – came on April 7, 1971. However, one of the wells, B-4, continued burning, as there was difficulty intercepting it by way of a relief well. It was finally controlled from the surface, and was put out with a high-pressure water spray. Well B-4 was capped and declared dead on April 16, 1971.

By this time, the event had lasted 136 days. Still, on April 16, 1971, the estimated rate of oil being released was 20 barrels per day. The case was closed by the U.S. Coast Guard on May 17th, 1971. Shoreline oiling resulting from the incident was found between Caminada Pass and Bay Champagne. However, some oil from the incident was tracked to Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.…Robert Bea recalled that his bosses at Shell were surprised to learn that the oil traveled underwater all the way to the Yucatan Peninsula…. Bob Bea, who helped design the multi-well platform used on the Shell rig at Bay Marchand and later became a University of California professor, would serve in a key role investigating the cause of the April 2010 BP disaster. But for the 1970-71 Shell incident, Bea recalled that his bosses at Shell were surprised to learn that the oil from that incident traveled underwater all the way to the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. It took nine months to finally complete all the of relief wells to fully kill the 23 boreholes associated with the platform. Shell eventually removed the destroyed platform, built a new one, and redrilled the field. And as author Tyler Priest writes in his 2007 book, The Offshore Imperative: Shell Oil’s Search for Petroleum in Postwar America, the 1970-71 blowout at Bay Marchand “was a watershed event for the company, forcing the E&P [exploration & production] organization to refocus on safeguarding the environment and workers.” But Shell, to this day, like other oil companies, would continue to have leaks, spills and blowouts in their operations.

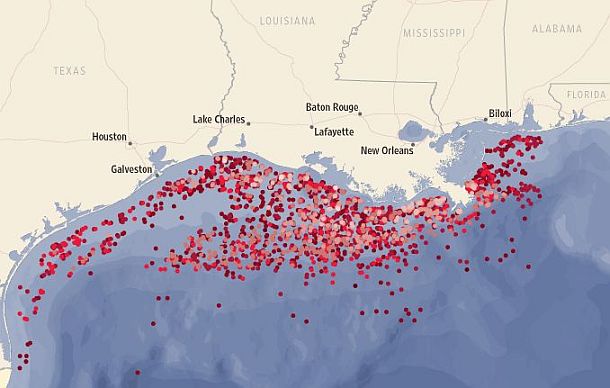

Later investigation of the Shell disaster at its Bay Marchand platform revealed that the plastic coating on the tubing in well B-21 sloughed off and plugged the well. In the course of wireline operations to clean out the well there was a time when the well was unattended and well-control valves were left incompletely closed.…A subsurface safety valve waiver, granted for com- pletion purposes, was also in effect at the time… In addition, a subsurface safety valve waiver – which had been granted for completion purposes – was also in effect at the time. The rest, as they say, is history: the well blew out and the fire ignited. Yes,1970-71 might seem like ancient history, and much has improved in the industry since then. Following the 1970-71 Shell blowout, which had been preceded earlier that year by a Chevron rig that also burned for months, industry began to focus more on safeguards for the environment and workers, while government regulators moved to tighten standards as well. Still, a look at the Wall Street Journal map below from 2010, shows there is no room for complacency in the Gulf of Mexico when it comes to potential offshore catastrophes that may be lurking in the existing stock of offshore rigs.

Map of oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico, compiled by the Wall Street Journal in December 2010, w/story, “Growing Old in the Gulf”.

The above map, compiled by the Wall Street Journal in 2010, shows Gulf of Mexico oil and gas rigs. The Journal found that roughly half of the region’s more than 3,000 rigs have been operating longer than their designers intended, with about a third dating back to the 1970s or earlier, well before the adoption of modern construction standards. According to the Journal’s 2010 analysis, of the 81 accidents on these facilities reported to the federal government in the past three years (presumably 2008-2010), in more than one-quarter of the cases the incident was related to the age of the structure. In this map, the darkest red indicates rigs dating to the 1940s, while the lighter pink shades indicate rigs of more recent vintage, installed in the 2000-to-2010 period.

|

“The Daily Damage” The above article is one in an occasional series of stories at this website that feature the ongoing environmental and societal impacts of industrial spills, toxic releases, fires, air & water pollution incidents and other such occurrences. Included among these will be both recent incidents and those from history that have had some impact either nationally or locally — i.e., have generated controversy; brought about government inquiry or political activity; and generally, have taken a toll on the environment, worker health and safety, and/or local communities. My purpose for including such stories here is simply to drive home the continuing and chronic nature of these occurrences through history, and hopefully contribute to public education about them so that improvements will be made in law, regulation, and industry practice, yielding safer alternatives in the future.— j.d. |

See also at this website, “Deepwater Horizon, Film & Spill,” a story about the making of the 2016 Hollywood film on the BP offshore oil rig disaster, plus a recap of the politics, media coverage, and corporate maneuvering during the real BP oil spill in the Gulf.

Additional stories on Shell Oil at this website include: “Shell Plant Explodes: 1994. Belpre, Ohio,” a story on a Shell plastics plant explosion & fire that killed three workers, caused the temporary evacuation of 1,700 residents, and polluted the adjacent Ohio River; “The Brent Spar Fight: Greenpeace, 1995,” about the battle over a proposed deep-sea disposal of an offshore oil storage spar; and, “Petrochem Peril: Shell Cracker History,” regarding Shell’s recently-built plastics plant and related infrastructure near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

For additional “oil & the environment” stories at this website see any of the following: “Burning Philadelphia,” a story about the 1975 Gulf Oil Co. refinery fire in that city; “Santa Barbara Oil Spill” about the 1969 Union Oil offshore oil well blow-out and pollution of California’s coastline; “Texas City Disaster,” about BP’s 2005 Texas City, TX oil refinery explosion and fire that killed 15 workers and injured another 180; “Barge Explodes in NY,” about a Bouchard gasoline transport barge docked at an ExxonMobil depot that exploded into a giant fireball in 2003, polluting waterways in the New York city area, shutting down water traffic, and shaking up communities for miles around; “Inferno at Whiting: 1955,” about an eight-day catastrophic Standard Oil/Amoco oil refinery explosion and fire near Chicago; and “Oil Fouls Montana,” profiling an oil pipeline leak that fouled the Yellowstone River in January 2015.

In addition, these and other environmental stories can be found at the “Environmental History” page, including, for example: “Burn On, Big River,” about the history of pollution-related Cuyahoga River fires near Cleveland, Ohio; “Paradise,” a story that uses a John Prine song as introduction to some history about Kentucky strip mining and the demise of a small town there; and “Power in the Pen,” a profile of the impact of Rachel Carson’s historic book on chemical pesticides, Silent Spring.

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 15 February 2015

Last Update: 16 January 2024

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Offshore Oil Blaze, Shell: 1970-71,”

PopHistoryDig.com, February 15, 2015.

____________________________________

Books at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Adminis-tration, Hazardous Materials Response Division, Oil Spill Case Histories, 1967-1991: Summaries of Significant U.S. and Inter-national Spills, Report No. HMRAD 92-11, Seattle, WA, September 1992.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Admin-istration (NOAA), “Shell Platform 26; Gulf of Mexico, Louisiana, December 1, 1970,” IncidentNews, NOAA, Washington, D.C.

“IFP. Platform Databank on Accidents to Drilling Vessels or Offshore Platforms (1955-1989),” #7032, U.S. Coast Guard POLREP file.

United Press International, “Shell Oil Plat-form Is Ablaze in Gulf; 2 Are Dead and 57 Are Rescued,” New York Times, December 2, 1970.

“Fire Fighters Begin Gulf Rig Battle,” Arizona Republic (Phoenix, AZ), December 5, 1970, p. 41.

“Shell Tries to Plug Burning Oil Wells,” Washington Post/Times Herald, December 7, 1970, p. 10.

United Press International, “Oil Crews Drill Under Fire in Gulf,” Chicago Tribune, December 7, 1970.

Associated Press, “Offshore Oil Fire Curbed As a Wild Well Is Plugged,” New York Times, December 31, 1970.

“Threaten Court Action Against Oil Companies,” Houma Daily Courier (Houma, LA), January 14, 1971.

Associated Press, “Wild Oil Well Killed in Gulf”[8th well of 11], New York Times, March 21, 1971.

K. Edmiston, “Shell Fire Dying Peacefully,” Oil Industry 6: 1971, pp. 34-41.

“Offshore Oil Blaze Blasted Out After Burning Since Last Dec. 1,” New York Times, April 13, 1971, p. 36.

Robert T. Miller and Ronald L. Clements, Shell Oil Co., “Reservoir Engineering Techniques Used To Predict Blowout Control During the Bay Marchand Fire,” Journal of Petroleum Technology, Vol. 24, No. 3, March 1972, pp. 234-240.

Jack Doyle, Riding The Dragon: Royal Dutch Shell & The Fossil Fire, Boston: Environ-mental Health Fund, 2000, 351pp.

Tyler Priest, The Offshore Imperative: Shell Oil’s Search for Petroleum in Postwar America, Texas A&M University Press, April 2007, 317pp.

David Hammer, “Louisiana Has Always Welcomed Offshore Oil Industry, Despite Dangers,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), Sunday, July 18, 2010.

John Donovan, “Shell Bay Marchand 1970 Well Blowout in the Gulf of Mexico,” RoyalDutchShellplc.com, July 27th, 2010.

Ben Casselman, “Aging Oil Rigs, Pipelines Expose Gulf to Accidents,” Wall Street Journal, December 14, 2010.

“Aging Oil and Gas Infrastructure Threatens Louisiana Gulf Coast,” Times-Picayune /Nola.com, December 15, 2010.

“Growing Old in the Gulf,” Wall Street Journal, December 2010 (formerly posted interactive map of aging offshore oil rigs for nine companies by date of platform construction).

Ed Warner (geologist) “The Great Gulf Blowout: Understanding the Blame Game,” TheModerateVoice.com (Posted by Dr. Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Managing Editor of TMV and Columnist, June 15, 2010).

Craig E. Colten, Jenny Hay, and Alexandra Giancarlo, “Community Resilience and Oil Spills in Coastal Louisiana,” Ecology and Society, Vol. 17, No. 3, Art. 5, 2012

Jason P. Theriot, American Energy, Imperiled Coast: Oil and Gas Development in Louisiana’s Wetlands, LSU Press, 2014, p. 86.

Associated Press, “Fire Spreading on Oil Rig, Control May Take Weeks,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, December 4, 1970, p.8.

Bob King, Electronic correspondence with photographic attachments to Jack Doyle at: jdoyle@PopHistoryDig.com, September 29 and October 1, 2016.

_____________________________________________