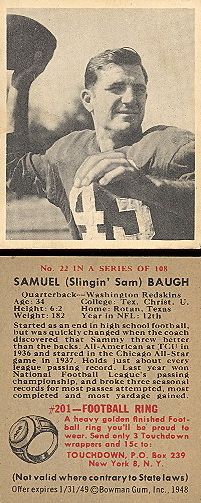

It was December 1937 in Chicago. The Washington Redskins professional football team had come to town to play the fearsome Chicago Bears in the National Football League championship game at Wrigley Field. It was a bitterly cold day with frozen turf. Washington, although a good team, wasn’t given much of a chance against “the big bruising Bears,” as Washington Post reporter Shirley Povich called them. But the Redskins had a new powerful weapon in the person of Sammy Baugh, their 23-year-old rookie running back.

Sammy Baugh, quarterback for the Washington Redskins, in action during a 1942 game vs. the Chicago Bears.

Baugh had come out of the college ranks, an innovative “passing” back, still something of a rarity in professional football at that time. In his college career at Texas Christian University (TCU), Baugh was an All-American who had led the nation in passing in his junior and senior years and finished fourth in 1936 Heisman Trophy voting. He had helped TCU to victories in the Sugar Bowl and Cotton Bowl. But Sammy Baugh’s professional career — played entirely with the Washington Redskins over 16 years — would be even better. In fact, he would change the way pro-football was played. “The history of pro football simply cannot be written without the story of Slingin’ Sammy,” says Washington Post sports columnist Michael Wilbon.

The Forward Pass

In the late 1930s when Sammy Baugh arrived in Washington, throwing the ball in football games — i.e., the forward pass — was still quite new, especially in professional football. Pro football was then second fiddle to college football, which was much more popular. In fact, the first time the passing technique had been used in football was at the college level, dating to an 1895 game between North Carolina University and the University of Georgia — an illegal use, it turns out, not then “approved” by the rules of play. Passing began at the college level, and slowly made its way to the pros, where it was used only sparingly by the early 1930s. But the first officially approved forward pass also occurred at the college level — in September 1906 when St. Louis University used it against Carroll College of Wisconsin. St. Louis University, however, was in the Midwest, and due to the nature of communication in those days — primarily newspapers — not many other colleges “back East” had heard of or used the technique, so its adoption by other schools was slow. But in 1913 a then little-known minor school named Notre Dame used the forward pass in a surprise win over a highly-touted team from Army. The technique demonstrated how a smaller Notre Dame team could use it to their advantage in beating the bigger Army team ( Knute Rockne then played end for Notre Dame and Gus Dorais, quarterback). After that game, the forward pass began to get more notice. A variety of college coaches and teams all experimented with passing and new formations — among them: Knute Rockne, who later became a coach at Notre Dame; Pop Warner, who used it as a college coach; Jim Thorpe and the Carlisle Indians; Alonzo Stagg at the University of Chicago; Johnny Heisman at Georgia Tech; various Ivy League teams; and others.

1997 book on Sammy Baugh’s TCU years by writer Whit Canning and editor Dan Jenkins of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

Swinging Tire

Sammy Baugh was born in Texas in 1914, and played three sports in high school at Sweetwater, Texas — football, basketball and baseball. In preparing to play for his high school team, Baugh practiced with an old tire strung from a tree which he would try to throw the ball trough while the tire was swinging and he was on the run. He developed a strong arm and pretty good accuracy. And although he did well in high school football, Sammy had his heart set on becoming a professional baseball player, and that’s the sport where he would pick up the name “slingin’ Sammy.” A sportswriter impressed with Sammy’s throwing arm as a college third baseman is credited with giving him that nickname.

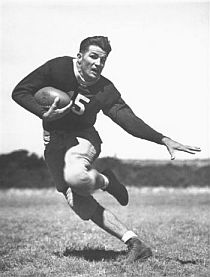

December 1936 AP photo of TCU star running back, Sammy Baugh.

At TCU, it was Sammy’s football play that would put him in the big time — although he remained a very good baseball player at TCU as well. However, in football as a college junior, he threw for 1,241 yards and 18 touchdowns. TCU only lost one game that year, to national champion SMU.

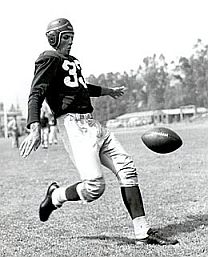

As a senior at TCU, Baugh threw for 1,196 yards, completing 50.5 percent of his passes. He led the nation in both passing and punting his final two seasons at TCU.

Many believe that Baugh’s performance at TCU helped bring national press notice to Texas football at a time when press coverage tilted to eastern sports teams. And although Baugh did not win Heisman Trophy in 1936 — he finished fourth in the voting — his performance is believed to have opened the door for his successor at TCU, Davey O’Brien, who did win the Heisman two years later.

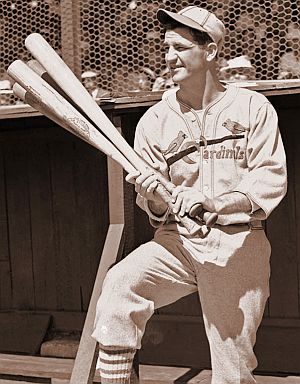

Sammy Baugh during his short-lived baseball career with the St. Louis Cardinals.

Baugh had been a star third baseman for TCU, and drew the notice of a few scouts. Rogers Hornsby, the famous St. Louis Cardinals baseball Hall-of-Famer, was then a St. Louis Cardinals scout, and in the spring/summer of 1937, he signed Baugh to play with the Cardinals.

However, Baugh was farmed out to the minor league Columbus team after being converted to shortstop, and then was sent even lower down in the minor league system to Rochester. There, Baugh still had to play behind Rochester’s starting shortstop, Marty Marion, who would go on to the major leagues and become a Cardinals regular for 11 years. Baugh knew he would never be as good as Marion.

“The other [problem] was I couldn’t hit that curve [ball] very well,” Baugh would later say. “So I left in August [1937] to play football, and after that I stuck with football.”

Preston Marshall

But the courting of Sammy Baugh by Washington Redskins owner George Preston Marshall had begun when Baugh was still at TCU. Marshall’s Washington Redskins professional team, in fact, was then newly arrived in Washington, as Marshall had moved them from Boston where he lost money and failed to generate a fan base. But Marshall’s fortunes would change in Washington, and Baugh would become one of his best new assets. Baugh later described his early meetings with Marshall and the salary discussions:

“…In the spring of my last year, 1937, George Marshall brought me to Washington and offered me $4,000 to play with the Redskins. Now down here in Texas, no one knew anything about pro football. They didn’t even know what it was. I didn’t know if I could make it in pro football, and since Dutch Meyer had offered me a job as freshman coach, I told Mr. Marshall I thought I was going to stay in Texas and coach. “…So I asked Mr. Marshall for $8,000, and I finally got it. Later I felt like a robber when I found out what Cliff Battles [a Redskins star] and some of those other good players were making… If I had known what they were getting I’d have never asked for $8,000…”

– Sammy Baugh See, I still wanted to be a baseball player, but I wanted a coaching job to fall back on.

Anyway, the summer after I got out of college I went to Chicago to play in the College All-Star football game against Green Bay. I talked with the rest of the boys on the All-Star squad and found that a bunch of them were going to play pro football. I found that most of them were just like me — that they hadn’t been out of the country too often themselves — and that I could play ball better than 99% of them. So I became more confident. As it turned out, we beat Green Bay, and then Mr. Marshall got after me pretty hot.

I didn’t know how much pro players were making, but I thought they were making pretty good money. So I asked Mr. Marshall for $8,000, and I finally got it. Later I felt like a robber when I found out what Cliff Battles [a Redskins star player] and some of those other good players were making. I’ll tell you what the highest-priced boy in Washington was getting the year before — not half as much as $8,000! Three of them — Cliff Battles, Turk Edwards and Wayne Millner — got peanuts, and all of ’em are in the Hall of Fame now. If I had known what they were getting I’d have never asked for $8,000….”

“Which Eye?”

Sammy Baugh at the Polo Grounds in New York, December 1938.

“They tell me you’re quite a passer,” said Flaherty, handing Baugh a football.

“I reckon I can throw,” Baugh answered.

“Let’s see it. Hit that receiver in the eye,” said Flaherty, pointing to a man running down the field.

“Which eye?” said Baugh.

For years, this exchange was believed to have been more urban legend that truth, but Washington Post sportswriter Shirley Povich confirmed it with Baugh himself in the 1990s. Baugh admitted the exchange was true, adding it was the one time he had been a little too flip. “Yep, ah said it,” he acknowledged in his Texas drawl to Povich. “First and last time in my life ah was cocky.” But Baugh would soon show he had something to be cocky about.

Threw Spirals

At 6′ 2″ and 182 pounds, Baugh was a good size for a throwing back. He also had large hands, and could grip the ball in a way at the laces to send it skyward in a spiraling fashion, achieving both accuracy and distance when he threw it. And throw it, he did.

In his first game, and the Washington Redskins first game in Washington at Griffith Stadium, Baugh completed 11 of 16 passes for 116 yards as the Redskins defeated the New York Giants, 13-3. Baugh’s passing, still new to the NFL, would become a key part of Washington’s attack. Washington Post reporter Shirley Povich greeted Baugh’s performance with high praise: “There was Slingin’ Sammy Baugh, putting his college reputation squarely on the spot, and justifying every advance notice with his magnificent forward-passing barrage against the Giants.” In the 11-game season that year, the rookie Baugh set an NFL record, completing 91 of 218 attempts and throwing for a league-high 1,127 yards, taking the Redskins to the NFL championship. Baugh was also defensive back and the team’s punter, or quick kicker in those days.

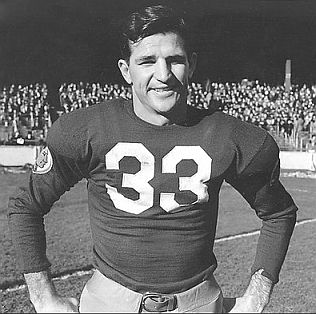

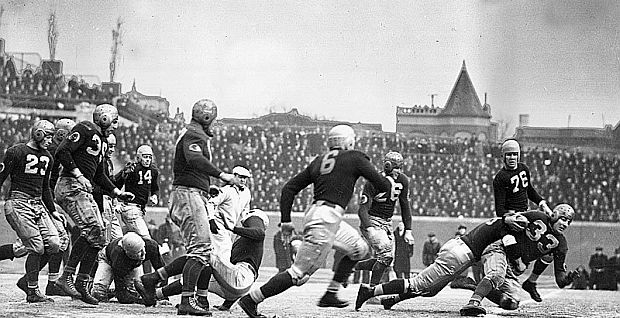

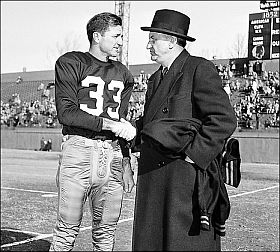

Sammy Baugh, No. 33, of the Washington Redskins, being tackled, far right, during NFL Championship game at Wrigley Field in Chicago on December 12, 1937, in which the Redskins prevailed, 27-21, on stellar play and passing heroics of Sammy Baugh.

The 1937 NFL championship featured the Western Division’s Chicago Bears (9-1-1) vs. the Eastern Division’s Washington Redskins (8-3). It was only the fifth time the annual NFL championship game had been played. Washington was the distinct underdog, not expected to have much chance against the “Monsters of the Midway” as the Bears would later be called. The contest was held on December 12, 1937, on a bitterly cold day on frozen turf at Wrigley Field in Chicago. The recorded attendance that day was 15,870. This was, of course, long before the Super Bowl and television. Players still played both offense and defense then, including running backs, and they had no face masks. The game was a lot rougher then as well. Quarterbacks were not protected and could be hit at will until the end of the play. In the Chicago game, in particular, Baugh was targeted by certain Bear players — linebacker and fullback Bronco Nagurski among them — who were trying to knock him out of the game. In pile ups, there was also some purposeful Sammy Baugh leg twisting.

In that championship game, the Bears had pinned Washington to their own five-yard line in the early minutes of the game, pushed up against the end zone. On first down, Baugh called for “punt formation,” but in the huddle told his teammates, “we’re gonna pass.” Passing, then used sparingly at the professional level, was hardly ever used on first down, and certainly not when a team was deep in their own territory. So Baugh got some weird looks on the call from his teammates. With the Bear lineman charging hard to block a punt, Baugh calmly tossed a pass to halfback Cliff Battles, who then ran for 42 yards. A few plays later Washington scored, and went on to win the game, 28-to-21. Baugh in that game turned in a stellar, championship performance, completing 17 of 34 passes for 352 yards — an astounding number even by modern day passing standards. Baugh’s passing yardage alone that day was more yardage than the entire Chicago offense had managed. He threw three touchdown passes — of 35, 55 and 78 yards. “Baugh was a one-man team,” one of the Bears coaches told reporters after the game.

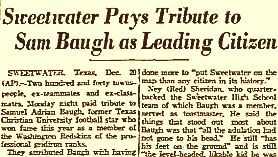

Dallas Morning News, December 21, 1937.

The townsfolk praised Baugh and said he done more to “put Sweetwater on the map that any citizen in history.” Red Sheriden, one of Baugh’s former Sweetwater High School football teammates, said that “all the adulation had not gone to his head,” and was still “the level-headed, likeable kid he was back in 1931 and 1932 when in high school.” Baugh’s high school coach Ed Hennig, was credited with teaching Baugh both football and modesty.

|

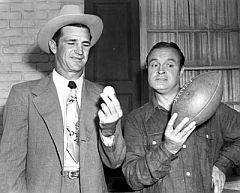

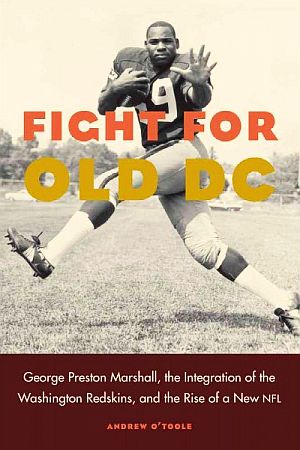

The Preston Marshall Show Back in Washington, Redskins owner, Preston Marshall, was setting out to build a business empire around his new team. Marshall was a colorful character who had once dabbled in the business of Vaudeville entertainment, dated Hollywood star Louise Brooks, and married another film star, Corinne Griffith. Marshall had been the owner of a chain of laundries in Washington, built up from a single store founded by his father — a business which Marshall later sold for a considerable profit. By the time Sammy Baugh was signed, Marshall had only been in the football business for a few years. In the early 1930s he and three other partners acquired a National Football League franchise in Boston naming their team the Boston Braves. By 1936, Marshall had gained sole control of the team and renamed it the Boston Redskins. But the team fared poorly, was not supported by the fans, and Marshall moved the team to Washington in 1937, the year he signed Sammy Baugh.  Preston Marshall as a younger man. In bringing notice to his team, Marshall also sought the help of sportswriters. “I need the support of you guys,” he said to reporters, according to Povich, who was among those Marshall was pitching. “I’m paying Sammy Baugh $8,000, and I need to put 12,000 people in the park [Griffith Stadium] to break even.” In 1937 the Redskins sold 958 season tickets. By 1947, with the help of Marshall’s promotional flair, all of the stadium’s 31,440 regular seats were selling out. Marshall was also something of a showman, and installed entertainment for the fans with a band and a team song, “Hail to The Redskins.” He also once paid for an entire train of multiple cars to take 10,000 Redskins fans to a New York Giants game in 1937. When Baugh first came to Washington, Marshall also insisted he wear cowboy boots and a Stetson hat, even though Baugh was more small-town boy than Texas cowboy.  Sammy Baugh & Preston Marshall, believed to be sometime in the 1940s. But one area where Marshall was not progressive was in the matter of racial integration, believed related to his southern states business strategy (see related book, posted below in “Sources”). Some pro teams had begun signing and drafting black players in 1946-1949, but it wasn’t until 1962 when Marshall did. And that came about only after Interior Secretary Stewart Udall threatened to revoke the Redskins’ 30-year lease on the new D.C. Stadium (RFK Stadium), paid for with government money. Marshall was also a meddlesome owner on the field at times, frustrating and firing his coaches. Baugh, in fact, played for ten different coaches, a fact which may have held Sammy back from an even greater career. But Sammy Baugh was undoubtedly the best investment Preston Marshall ever made, as Sammy helped put the Redskins on the map in those early years, boosting the organization and its business. |

Passing From the “T”

Sammy Baugh began his career with the Redskins as a tailback, playing from the single-wing and double-wing formations. Baugh was responsible for passing and punting, while another back, Riley Smith, handled the play-calling duties. But all that began to change in the 1940s when the Redskins and other teams began to adopt the T-formation. In this formation, the quarterback became a more central figure, taking responsibility for both play-calling and passing, giving the quarterback full control of the offense. And this is where Baugh excelled — making the forward pass a more a designed-in part of the game, played from the line scrimmage. With the “T”formation and passing now part of the planned attack, Baugh helped bring a more exciting form of play to the pro game. From 1940 to 1949, Sammy Baugh led the league in passing five times. Together with his passing championship from his rookie season, Baugh would claim six career passing titles; a feat only equaled by Steve Young of the San Francisco 49ers in the 1990s.Baugh would direct the team to four division titles and two NFL championships in1937 and 1942. In a career spanning 162 games, he threw 1,693 completed passes in 2,995 attempts, a 56.5 percent completion rate. He totaled some 21,886 passing yards and 187 touchdowns. At the time of Baugh’s retirement, he held a number of NFL and Washington Redskin records, some of which still stand at this writing.

Baugh played his entire 16-year career with the Washington Redskins through the 1952 season. But in Washington, he also had a few bad games, the most notorious of which was the 73-0 drubbing by the Chicago Bears for the 1940 championship. He was pulled out of the game to spare him embarrassment, after completing 9 of 16 passes for a total of 91 yards with 2 interceptions. But two years later, Baugh and the Redskins took some satisfaction in stopping Chicago’s perfect season, then at 11-0 until Washington beat them 14-6 in the championship game. In 1945, Baugh compiled his best statistical season, completing 128 of 182 attempts for 1,669 yards and a 70.3 percent completion average — an NFL record that stood for decades before being surpassed in 1982 by Ken Anderson of the Cincinnati Bengals who posted a completion rate of 70.6 percent. One of Baugh’s most impressive games came fittingly on “Sammy Baugh Day” in 1947 when he threw six touchdown passes against the Chicago Cardinals. But by all accounts, Baugh worked hard at his craft, as it was said that in practice he liked to complete 100 consecutive passes before leaving for the day, and missing one, he’d start again.

All-Around Player

Sammy Baugh played in the day of 'two way' players, excelling as a defensive back as well as a quarterback, here making an interception.

Baugh’s agility and quarterback sense made him an excellent aerial defender, and he shares a defensive record to this day of making four interceptions in one game. In 1940, he intercepted 11 passes in just 10 games, which Washington Post columnist Thomas Boswell has singled out as especially noteworthy. “How good is that?,” says Boswell, adding that “no NFL player has intercepted 11 passes since 1981 and the last man to have more than an interception per game was Night Train Lane in 1952.” In 1943, Sammy was one of the few players to win a rare pro football “triple crown” distinction in offensive, defensive, and special teams categories — passing, punting, and interceptions. In 1943 he completed 133 of 239 attempted passes for 1,754 yards and 23 touchdowns. In punting, his 50 kicks averaged 45.9 yards for a total 2,295 yards. And he also led the league that year in interceptions with eleven. Baugh is the only player ever to lead the league in offensive, defensive and special teams categories. As a passer, he was known for his ability to accurately connect with his receivers over long and short distances in the face of onrushing defensive linemen. In nine seasons — 1937, 1940, 1942, 1943 and 1945-49 — he led the NFL in completion percentage. Sammy also passed for six touchdowns in a single game on two occasions — once in October 1943 and again in November 1947.

After retiring as a player in 1952, Baugh returned to his 7,600-acre ranch in Rotan, Texas, about 95 miles south of Lubbock. Although ranching would become a major part of his life thereafter, he also stayed involved with football.In 1955, Baugh began five years of college coaching at Hardin-Simmons College at Abilene, Texas. He was also a coach of freshman football at Oklahoma State University and a backfield coach at the University of Tulsa. In 1960 and 1961 he was head coach of the New York Titans of the new American Football League — the team that would later become the New York Jets. In 1964, he became head coach of the Houston Oilers, posting a 4-10 record. Thereafter, however, he decided he needed to focus on his West Texas cattle operation.

In November 1993, during a pre-game ceremony at a TCU football game, the university retired Baugh’s No. 45 college jersey. His No. 33 Washington Redskins jersey was also retired, and is the only one the Washington organization has retired to date. And each year since 1959, the Sammy Baugh Trophy has been awarded to the nation’s top collegiate passer.

Sammy Baugh was also a good punter.

Baugh had married his college sweetheart, Edmonia Smith, of Sweetwater, Texas in 1938. They had five children, followed by 11 grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren. His wife died in 1990, and he lost a son in 2006. But Baugh himself lived to the age of 94, when he died of kidney failure and pneumonia. The doctor said his body just wore out.

“Changed The Game”

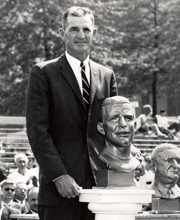

Sammy Baugh at Hall of Fame induction, 1963.

Putting some perspective on this accomplishment, Washington Post sports columnist Thomas Boswell observes: “What Babe Ruth’s home runs did for baseball in the early 1920s, Baugh’s bombs did for the NFL in the late ’30s.” In 1936, the season before Baugh arrived, the average NFL team scored 11.9 points a game and completed 5.6 passes. “What Babe Ruth’s home runs did for baseball in the early 1920s, Baugh’s bombs did for the NFL in the late ’30s.”

– Thomas Boswell The NFL completion percentage was 36.5. The entire sport threw only 67 scoring passes. As a rookie, starting only five games, Sammy Baugh broke the NFL completion record with 81. By 1940, he was completing 62.7 percent of his passes.

Before Baugh came,” says Boswell, “only one man ever passed for 1,000 yards in a season. By 1947, Baugh completed 210 passes for 2,938 yards… If Ruth [in baseball] quadrupled the prevailing view of how many home runs were possible in a season, then Baugh tripled the notion of how much yardage a team could gain through the air.” Baugh was a trendsetter, who influenced other great quarterbacks of his day, including Sid Luckman in 1942 and Otto Graham in 1946, who also helped move the game into its modern era.

For those who saw him play, Sammy Baugh remains one of the game’s best. Said legendary sportswriter Grantland Rice in 1942: “Sammy happens to be just about the most valuable football player of all time, according to most pro coaches I’ve talked to.” In the 1990s, sportswriter Dan Jenkins a Fort Worth, Texas native who saw Baugh play at Texas Christian University and as a pro, called him “the greatest quarterback who ever lived, college or pro.” Steve Sabol, president of NFL Films and a noted football historian told the Washington Post’s Michael Wilbon about an experience he had as a young boy seeing Sammy play:

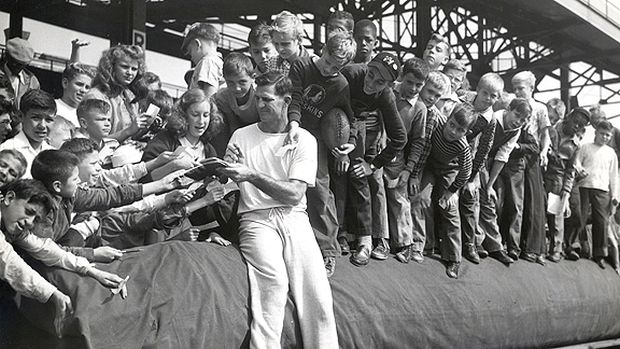

“I was 9 years old and my father took me to Shibe Park in Philadelphia to see the Eagles play the Redskins. It was 1951. My dad said: ‘See the man wearing Number 33? That’s Sammy Baugh.’ That’s all he said.”

“It was like pointing out the Empire State Building, the Washington Monument or Niagara Falls. ‘That’s Sammy Baugh.’ That’s all that needed to be said to anyone who followed pro football in the 1940s and early 1950s.”

Sammy Baugh, quarterback for the Washington Redskins, attending to an admiring crowd of young fans and autograph seekers during height of his career.

Additional pro football stories at this website include: “Bednarik-Gifford Lore,” a story that tracks the respective football careers of Philadelphia Eagles linebacker, Chuck Bednarik, and New York Giants running back, Frank Gifford, and their famous gridiron collision of November 1960. Joe Namath’s career, AFL-NFL history, and Namath’s famous Superbowl III prediction in 1969, are all covered in the story, “I Guarantee It.” And “Celebrity Gifford, 1950s-2000s,” provides a detailed look at the advertising, sports broadcasting, and TV/film/radio career of Frank Gifford. See also the “Annals of Sport” category page for other sports stories.

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________

Date Posted: 21 December 2008

Last Update: 19 October 2018

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Slingin’ Sammy, 1930s-1950s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, December 21, 2008.

_____________________________

Football Books at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“Boston Bravery,” Time, Monday, Aug. 19, 1935

See Sammy Baugh in action at “Sammy Baugh Video, 1937-1952,” at this website.

Shirley Povich, “Baugh Stars as Redskins Annex Title,”Washington Post, December 13, 1937, p. 1.

“Heroes for Pay,” Time, Monday, November 1, 1937.

Associated Press, “Sweetwater Pays Tribute to Sam Baugh as Leading Citizen,” Dallas Morning News, December 21, 1937, Section 2, p. 7.

“PowWow,” Time, Monday, Dec. 12, 1938.

Joe Holley, “A Redskin Forever Hailed: Slingin’ Sammy Baugh Passed His Way Into Gridiron History,” Washington Post, Saturday, February 4, 2006, p. C-1.

Shirley Povich, “Slingin’ Sammy Baugh: The Magic of Number 33,” Washington Post, From paperback book manuscript posted online.

By Shirley Povich, “George Preston Marshall: No Boredom or Blacks Allowed,”Washington Post, From paperback book manuscript posted online.

Shirley Povich, “Sammy Baugh Retires,” Washington Post, December 10, 1952.

“Sammy Baugh,” Wikipedia.org.

“Biography – Sammy Baugh,” Football Hall of Fame, Class of 1963.

Myron Cope, “A Life For Two Tough Texans,” Sports Illustrated, October 20, 1969.

Dennis Tuttle, “Still Slingin’,” Sporting News, November 7, 1994.

Larry Schwartz, “Baugh Perfected the Perfect Pass,” Special to ESPN.com, 2007.

Scott Hurrey, “Sammy Baugh – The Best Ever?,” TheHogs.net.

1930s — Sammy Baugh, “Face of the Program,” ESPN.com

“King of the Texas Rangers,” Wikipedia.com.

Associated Press photos.

Richard Goldstein, “Sammy Baugh, N.F.L. Great, Dies at 94,” New York Times, December 18, 2008.

Joe Holley and Bart Barnes, “The First of the Gunslingers — Quarterback Led Redskins to Two Titles, Football Into Modern Era,” Washington Post, Thursday, December 18, 2008, p. E-1.

Michael Wilbon, “Getting In a Word For Slingin’ Sammy,” Washington Post, Friday, December 19, 2008, p. E-1.

Thomas Boswell, “Rock of the Redskins, Arm of the NFL,” Washington Post, Friday, December 19, 2008, p. E-1.

Samu Qureshi and Valerie Grissom, “Team Report” Cover Story, (Letters from Hall of Fame quarterback Sammy Baugh and owner George Marshall reveal the Redskins’ early struggles on — and off — the field.) Washington Post Magazine, Sunday, August 2, 2009, pp 8- 13+.

The Intercollegiate Football Researchers Association.

____________________