Film poster for 1989's “Glory.” From top right: Morgan Freeman, as the unit’s sergeant; Denzel Washington as runaway slave who becomes soldier; and Matthew Broderick who plays the youthful Colonel Robert Shaw. Click for film.

Equally important in the film are Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman and Andre Braugher, each of whom play prominent roles.

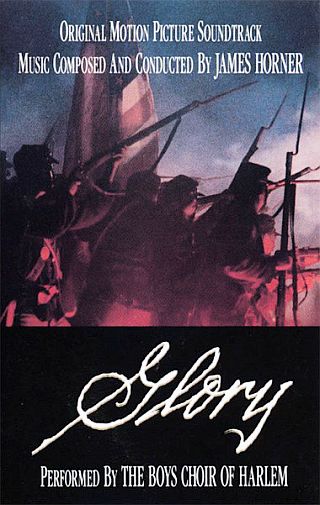

The film highlights the racial bigotry and discrimination the 54th faces in its bid to distinguish itself as a battle-worthy fighting force. But what adds to the poignancy and power of this film in the telling of black heroism is its moving musical score.

Music Player

Glory Theme

The music is by James Horner (1953-2015), an American composer, conductor, and orchestrator of film scores, known for the use of choral and electronic elements in his film work. And with the Glory score, Horner created some especially memorable and moving music, making effective use of the Harlem Boys Choir, giving the film a spiritual/hymnal quality at times. One reviewer of the film’s music, Jonathan Broxton, looking back on the film 30 years later, has noted:

…Glory is, in my opinion, one of the most accomplished emotional scores of Horner’s entire career, a bonafide masterpiece that brings the lives and deaths of these men who gave up everything roaring into contemporary relevance. It doesn’t matter that this all happened 100 years or more before we were born; the hopes and fears and unrealized dreams of these men, and the things they stood for, are just as important today as they were in 1863, and Horner’s music plays a major part in allowing us to feel that. The fact that it’s also beautifully written and orchestrated and performed is just icing on the cake….”

Overall, Horner’s music in this film not only supports the unsung story of African American “glory” and heroism in the Civil War – but is also a stand-alone accomplishment, worthy of listening apart from the film, conveying its own emotive powers. In the film, the music is an essential compliment to drawing out its various moments of struggle, pathos, and determination. More on the music a bit later. First, some background and overview on the film story by way of its trailer — and later, a striking piece of sculpture that helped inspire the film.

The casting of the black soldiers for the film is superb, as the story is told partially from their perspective. Morgan Freeman plays a battle-field gravedigger who rises to become Sgt. Major John Rawlins. He is the conscience of the regiment and key aide to Shaw and helps to inspire and unite the troops. Denzel Washington plays a runaway slave who becomes Pvt. Silas Trip, a tough, feisty defender of his race with a keen sense of himself, angry and skeptical. Andre Braugher, making his feature-film debut as Cpl. Thomas Searles, plays a very proper, Boston-born-and-bred young black man who is both an intellectual and boyhood friend of Shaw’s. Thomas sleeps with his glasses on and is nicknamed “Snowflake” by tent-mate Trip, who dislikes him. Jihmi Kennedy plays Pvt. Jupiter Sharts, a country boy who stutters but is a crack shot with a rifle.

A few of the volunteer recruits for the 54th during training. From left: Pvt. Jupiter Sharts (Jihmi Kennedy); Pvt Silas Trip (Denzel Washington), and Sgt, Major John Rawlins (Morgan Freeman) who becomes a troop leader.

Based largely on a true account, the creation of the Massachusetts 54th regiment of all black soldiers had the support of the Massachusetts Governor, John Andrew, an abolitionist who believed the regiment would be a step toward a wider acceptance of blacks by whites. Black leader, Frederick Douglass, also supported the formation of the unit, and his two sons volunteered to serve in it. Douglass believed that blacks should be involved in a fight that was, at least in part, for their own freedom. In the film, Douglass appears a couple of times, including once with the governor on the reviewing stand at a military parade.

The young Colonel Robert Shaw (Broderick) at right, in Boston, along with Thomas Searles (Braugher), his boyhood friend, who becomes the 54th’s first volunteer at word of the unit’s forming.

But Shaw, earlier as a soldier at age 23, experienced the horrors of the Civil War close up during fierce fighting at Antietam, where he was wounded and shaken by what he saw on the battlefield. Still, when offered the command of the 54th by the governor, he becomes determined to succeed.

Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Procla-mation of September 22nd, 1862 (effective January 1, 1863), in addition to freeing all slaves, also stated that blacks would be “received into the armed services of the United States,” which moved Governor Andrew to authorize an all-black regiment.

Still, most military leaders, north and south, did not believe blacks could be made into a reliable fighting force.

In setting out on his task, Shaw enlists his white friend, Major Cabot Forbes, to be his confidant and second in command, played by Cary Elwes in the film. Shaw would also enlist an Irish drill sergeant to help discipline and toughen-up the black recruits, who came from disparate backgrounds. Most of the recruits and volunteers were free blacks from northern states along with some runaway slaves.

Shaw is shown at one point in the film, pushing recruit Jupiter Sharts to load and reload his rifle much quicker, and to do so under pressure, shouting at him while he attempts to muzzle-load his rifle, and firing a pistol behind his head several times, trying to simulate the battle chaos his men will face, insisting on their tough preparation.

Colonel Shaw, with pistol in hand, center, and repeatedly firing it at close range to harass Pvt. Sharts, while yelling at him to quickly re-load his rifle, in an attempt to demonstrate battlefield pressures the soldiers will face. Click for YouTube clip, 2:52.

Shaw, however, has his trials, attempting to bring these men into fighting form while needing to gain their respect. He fights the Army bureaucracy as well as the existing military hierarchy and fellow white officers who regard the all-black regimen as truly second class, and not worth any consideration, militarily or otherwise. Shaw reluctantly has to discipline Pvt. Trip at one point, ordering him to be flogged in front of the troops for an attempted desertion.

Pvt. Trip being tied to a wagon wheel prior to being flogged for alleged desertion, revealing scars from his slave days and earlier whippings. Colonel Shaw later learns the real reason Trip left camp.

Shaw later learns that Trip had left camp to find regular-issue shoes because the men were being denied these supplies by the Army quartermaster. Shaw is outraged, and confronts the racist quartermaster and wins some supplies for his troops, and later uniforms.

Pay, however, is another problem, with Shaw receiving a notice at one point that black soldiers will be paid less than white soldiers. This news is protested strongly by Trip, who instigates a resistance, tearing up his check, which in turn, moves Shaw to do the same, bonding men and officers together at that point, helping to form a cohesive unit. Also helping solidify the regiment, and demonstrating the resolve of it black soldiers, comes when Shaw reads a notice received from the Confederate command stating that all captured black soldiers and their officers would be shot. Shaw then states that any man wishing to leave the regiment would be honorably discharged if they chose to do so. None did.

Denzel Washington character, Pvt. Silas Trip (center), instigating a mass revolt among black soldiers in the 54th regiment upon learning their pay is less than white soldiers. Col. Shaw joins the protest, helping to galvanize & cohere the unit.

The disparate collection of volunteer soldiers soon becomes a capable unit, and at their send off they are put on public display, appearing as a formidable and sharply-dressed regiment on military parade through the streets of Boston, as shown in the film clip below:

Once deployed and heading south, the 54th and Shaw come under the command of General Harker, who pairs the 54th with another regiment of mostly freed slaves commanded by Colonel Montgomery. Coming upon the town of Darien, Georgia, Montgomery orders all the troops, including the 54th, to burn and pillage the town to the horror of Shaw, who refuses, calling the order illegal, but then complies under threat of losing command of the 54th.

Thereafter, Shaw and his unit continue to be consigned to mostly manual labor tasks, though they desperately want to prove themselves in battle. Shaw has tried the legitimate channels to gain combat assignments for this men, but then resorts to threatening higher ups Harker and Montgomery with revelations of their smuggling, looting, and graft unless the 54th is cleared for combat — which they finally receive. On July 16th, 1863, Shaw’s men engage in their first battle on James Island in South Carolina. In a forest, they shoot at the approaching Confederate soldiers, then engage in hand-to-hand combat using bayonets. They rout the rebs initially, but a bloody confrontation follows with some casualties. Soon to come, however, is their biggest challenge.

Later in July 1863, Shaw and his regiment have come to Morris Island, South Carolina, not far from Charleston Harbor. On the beach there, Shaw and officers from other regiments are briefed by General George Crockett Strong about the particulars of the Confederate Fort Wagner, the fortification and stronghold guarding the entrance to the harbor – a fortress the Yanks must take. Amidst the sound of shelling from the Union Navy vessels offshore, then bombarding Ft. Wagner with little effect, General Strong describes what lays ahead.

General George Strong, along with a group of his officers, assemble on the beach for a briefing about plans to take the nearly impenetrable Fort Wagner, shown in the distance, as Yankee ships offshore bombard the fort. A Union land assault is set, with Col. Shaw and the 54th volunteering to lead the charge the following evening.

First, the General ticks off a series of large cannons found at the fort: “Wagner mounts a ten-inch Columbiad, three smoothbore thirty-two pounders, a forty-two pound Carronade, a ten-inch Coast Mortar and four twelve-pound Howitzers…” There is also a garrison of 1,000 soldiers. But that’s not the worst part. The problem, Strong tells his officers, is the approach. “The ocean and the marsh leave only a narrow strip of sand, a natural defile through which we can only send one regiment at a time. Now our best hope is that leading regiment can keep the Rebs occupied long enough for reinforcements to exploit the breach. Needless to say, casualties in the leading regiment may be extreme.”

Col. Shaw, at far left, standing on the beach with other officers, listening to General Strong describe the weaponry, fortifications, and unfavorable geography for any attack on Ft. Wagner, volunteers the 54th to lead the charge.

Before Strong can finish, Col. Shaw calls forth: “General Strong, the 54th Massachusetts requests the honor of leading the attack on Fort Wagner.” Strong worries that Shaw’s men have not slept in two days, but Shaw promises that his soldiers possess the character needed for such a mission. And with that, the deed is set, and Shaw returns to his men.

The night before they go into battle, the 54th gathers around a campfire to sing spirituals. And one by one, some of the men rise to pray, seek God’s blessing on their battle, or offer other testimonials. Pvt Jupiter, Sgt-Major Rawlins, and Trip make speeches. Trip is a reluctant speaker, but does say he considers his fellow soldiers his family and that he loves the 54th. Col. Shaw, meanwhile, has given some personal letters to a newspaper journalist to mail, also urging him to remember what he sees on the battlefield there. By late afternoon the next day, Shaw prepares for the assault, dressing in his best uniform, then walking through the ranks of his men. The troop then begins their march through the coastal dunes to assemble on the beach for their attack on Ft. Wagner. As they go, they are cheered by white Yankee soldiers lining the path through the dunes, heading to their muster point. One yells, “Give ’em hell, 54th!” Here’s a film clip of that sequence:

Shaw, now on horseback on his way to joining his men on the beach, first takes his mount to the ocean’s edge away from the troop for a moment of reflection. In the evening light there, against a beautiful coastal scene, with waves gently rolling in as sea gulls dip-and-rise over the water, Shaw takes stock of the natural beauty; drinking it all in with every possible last morsel of his senses, knowing that certain death awaits him a short while ahead. These are likely his last few moments on earth.

Colonel Shaw, at ocean’s edge, drinking in the beauty of the natural world, knowing this may be among his last moments on earth before leading his regiment and near-certain death in their impossible assault on Fort Wagner.

It is then, during this scene, when Horner’s “Glory theme” rises and sweeps over the moment to musically embed Shaw’s last glimpses of earthly wonderment and natural beauty into our visceral memory. But at the same time, Shaw is surely feeling real fear, doubt, and hesitancy: This is it! There’s no turning back now! And the music helps us feel Shaw’s moments as if our own. It is a powerful and moving scene that is made more so by the haunting music.

Music Player

“Preparations For Battle”

Glory Soundtrack

The viewer-listener by this point has also had a steady course of the “Glory” motif played in different scenes throughout the film, so its effect in the “Shaw-by-the-sea” moment is magnified all the more. Shaw knows, and we all know, what’s about to come next.

Duty and commitment call; beauty and life must ebb away. Shaw then dismounts, sending his horse off up the beach with a smack on its hind quarters. Rejoining his regiment, he asks who among the troop will insure that the flag will be borne should its bearer fall. His boyhood friend, Thomas, steps forward: “I will,” says Thomas. Shaw then gives the order to “fix bayonets,” and then, “quick step,” as he leads the charge on the beach toward Ft. Wagner. This part of the score, at its end, follows the men on their charge, with more militaristic drumming and bombastic, battle-type sounds as the heroes of the 54th make their charge and begin to fall – Shaw, Trip, and others…

Scene from “Glory” showing early charge of the Massachusetts 54th amid exploding shells as they make their way along the beach for their assault on the heavily fortified Ft. Wagner. Here, Thomas and Trip are shown at left.

In the end, the charge of the 54th was not successful, as the film shows, with most of the principals falling. Seeing their Colonel fall, however, the men did rally and managed to breach the fort, whereupon the remaining troops faced another line of cannons and Confederates in their path, leaving viewers to complete the scene as the cannons fire and the film cuts away. An after-battle, next-day scene then shows Confederate soldiers burying the Union dead in an open pit, as the camera shows a dead Colonel Shaw rolling into the pit with his men, and then Trip, rolling in next, landing on top of him.

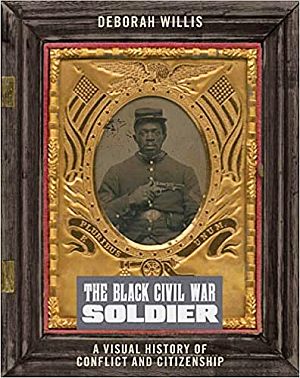

Although their Ft. Wagner assault did not prevail (though the fort was later taken), word of the 54th Regiment’s heroics encouraged the battle deployment of other black regiments. Over 180,000 African Americans would ultimately volunteer for the Union cause, their contribution cited by President Lincoln as helping turn the tide in the war, playing a key role in the Union’s ultimate victory.

Remembrance & Sculpture

Fortunately for history, there came in later years a series of books, art work, and sculpture commemorating Colonel Shaw and the Massachusetts 54th.

One artist’s rendition, circa 1890, a color lithograph, titled “Storming Fort Wagner,” by the Kurz & Allison Lithography Company, offers one perspective on the battle. It depicts the 54th at the fort, with Colonel Shaw in the vanguard of the attack, showing him being shot at the center of the scene. Also shown here, the black flag bearer at center with Colonel Shaw, was in the real battle, former slave William Harvey Carney, who belatedly in 1900, was the first African American to receive the Medal of Honor for his gallantry that day.

1890 color lithograph, titled “Storming Fort Wagner,” by the Kurz & Allison Lithography Company. Click for print.

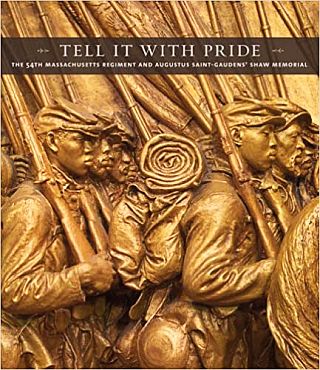

Beyond this illustration, however, perhaps the more notable remembrance of the Massachusetts 54th and Colonel Shaw is the 1897 bas-relief sculpture by Augustus Saint-Gaudens located on the Boston Common in Boston, Massachusetts, across the street from the Massachusetts State House.

2020 National Park Service photo of The Shaw Memorial at Boston Common. Actual setting includes a larger plaza not shown. The bas-relief sculpture is 11' x 14' and its subject figures are nearly life size. See photos below for more detail.

“The Shaw Memorial,” as it is known in shorthand, made its debut in 1897 with speeches and a dedication ceremony at the Boston Music Hall, on May 31st, 1897. The large monument – which stands 11′ by 14′, with sculptured figures that are nearly life size – has a prominent frieze of Shaw on horseback, accompanied by marching soldiers of the 54th. The sculpture in 2021 underwent a restoration, re-installed at its original location across from the State House. And in the closing credits of Glory, close-up camera shots of the sculpture were shown, highlighting the detailed work on the faces and equipment of the individual soldiers — some of which are shown here later below. In fact, those end-of-film frames of the sculptured African American soldiers in particular, with the backing of Horner’s score, no doubt had an impact on viewing audiences and beyond – perhaps helping to inspire future art and tribute sites.

1897 photo. Dedication of Augustus Saint-Gaudens's memorial to Robert Shaw and the Massachusetts 54th on Boston Common, May 31, 1897. The dedication included a procession led by some of the officers and soldiers who fought with the 54th in 1863. Massachusetts Historical Society photo.

In the memorial sculpture, Saint-Gaudens based the scene on Shaw and the 54th as they marched through Boston in 1863, at their departure for battle and points south. Saint-Gaudens, originally intended the memorial to depict Colonel Shaw alone astride his horse. However, Shaw’s family of abolitionists asked that the artist also depict the men who made possible the fame the Colonel had received.

A closer view of the Shaw Memorial reveals its three-dimensional context and life-like detail of its figures.

The work for Saint-Gaudens turned into a 14-year project, as he labored over details in rendering the final scene, which includes notable and quite amazing detail on the forms and faces of the soldiers, as seen in photos shown here. And since its unveiling in 1897, the sculpture has had a continuing impact on many who have seen it.

Another view of one section of the Shaw Memorial shows the sculptor’s fine detail of his subjects’ faces, dress, and equipment

In fact, some 80 years later, this memorial sculpture would provide at least some of the inspiration for the 1989 film, Glory.

Inspiration

The film’s screenwriter, Kevin Jarre, had been a fan of the Civil War since childhood. But reportedly, one day on the Boston Common, as Jarre explored the Shaw Memorial, he noticed at closer inspection that some of the soldiers in the rendering were black. Few people then, including Jarre, knew that blacks fought in the Civil War. So it occurred to Jarre as he gazed at the memorial, that this was a story that might have wider appeal. And with that, the seeds for Glory were planted, and off he went to do more research.

Jarre had also been a friend of Lincoln Kirstein, who was a big fan of Shaw and the Shaw Memorial, and had written a 1973 monograph, “Lay This Laurel,” about the regiment. Jarre also read the letters of Colonel Robert Shaw and other historical material. All of this figured into Jarre’s becoming committed to writing a screenplay – which he would later say he did in four weeks after holding up in a New York City hotel. “I never thought I could interest anybody in it,” he told the Los Angeles Times of his screenplay in 1990. “A Civil War epic, about black people? But I’d got really attached to the story.”

In the end, Jarre’s screenplay for Glory derived from three sources: 1) the personal letters of Robert Shaw, also published in book form, as Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune; 2.) Lay This Laurel, first published in 1973 as an album of greytone photographs by Richard Benson with the monograph by Lincoln Kirstein; and 3.) One Gallant Rush: Robert Gould Shaw & His Brave Black Regiment, a 1965 book by Peter Burchard. In addition to the books, Shelby Foote, noted Civil War historian and star of the Ken Burns epic documentary on the war, was a key consultant to the film.

Making The Film

Getting the screenplay to final film, however, was another story, as it often is. In this case, it took four years for the film to get major studio financing. Hollywood decision makers had rejected the project for years; it wasn’t quite in sync with “the conventional formulas for box-office success,” according to one source. But then came Freddie Fields, a former head of production at MGM/UA Entertainment Company. Fields became quite taken with the story in 1985: “It came as a real surprise to me that black troops fought so heroically in the Civil War, and I thought it could make a moving story that would also be socially and historically significant.” Fields would later say, “Getting this movie made…became a real passion for me.”

Portion of a promotional poster featuring film blurbs.

At its first release, the film received generally good reviews, some calling it “one of the best movies ever made about the American Civil War” and among “the finest historical dramas.” Richard Schickel of Time praised the movie’s “often awesome imagery and a bravely soaring choral score…” Denzel Washington’s performance as Trip received rave reviews by many, while Matthew Broderick’s Col. Shaw, although an earnest performance, had a mixed reaction.

Roger Ebert from the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film a 3.5 rating out of 4, calling it “a strong and valuable film no matter whose eyes it is seen through,” but he did note one recurring problem. “I didn’t understand why [the story] had to be told so often from the point of view of the 54th’s white commanding officer. Why did we see the black troops through his eyes — instead of seeing him through theirs?…” Similarly, in later years, the film has had more scrutiny along these lines, with a number of reviewers critiquing the film’s racial aspects, and that more should have been made of the black soldiers’ perspectives and former lives. For example, Shaw’s letters home received attention in the film, yet none of the black soldier’s characters or back-stories were similarly followed or developed.

Still, in the end, Glory was the first major motion picture to tell the story of black U.S. soldiers fighting for their freedom in the Civil War, and as such it helped open the door to further research and public education on the film and related subject matter.Glory was nominated for five Academy Awards and won three – Best Supporting Actor for Denzel Washington; Best Cinema-tography (Freddie Francis); and Best Sound (Donald O. Mitchell, Gregg Rudloff, Elliot Tyson, and Russell Williams II).

Sadly, however, James Horner’s film score for Glory was not nominated for an Academy Award, which many fans found puzzling. The score for The Little Mermaid took the prize that year.

However, Horner’s score was nominated for, but did not win, a Golden Globe award. His work on Glory did win a Grammy for Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television.

In addition, in one or more film production, directing, and/or acting categories, Glory also received awards from: the Golden Globe Awards, the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, the Kansas City Film Critics Circle, the Political Film Society, and the NAACP Image Awards.

VHS, DVD, and BlueRay editions of the film were produced between 1990 and 2008, some as special editions with extra features. The film also spurred sales of the existing books on Shaw and the 54 th Massachusetts regiment. In June 1990, Publishers Weekly reported that sales of both One Gallant Rush by Peter Burchard and Lay This Laurel by Lincoln Kirstein were boosted by the film’s release. An earlier special edition of One Gallant Rush that coincided with the film’s opening, in fact, had sold 40,000 copies by Mach 1990.

The “Glory Effect”

Glory also helped to prompt and/or inspire further inquiries, museum exhibits, additional books, and scholarly papers on the history and role of African Americans in the Civil War, and also some new monuments and sculptures.

The first scholarly collection of the Col. Shaw’s letters, edited by Russell Duncan and mentioned earlier – Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune – was published in 1992. Duncan would follow that volume with a Shaw biography in 1999, Where Death and Glory Meet: Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, University of Georgia Press. A number of other books on Shaw, the 54th, and/or African American involvement in the Civil War have been published since the film, some of which are shown or listed below in “Sources.”

“Tell It With Pride: The 54th Massachusetts Regiment and Augustus Saint-Gaudens' Shaw Memorial,” illustrated, 2013, Yale University Press, 228pp. Click for copy.

“For over a century, the 54th Massachusetts, its famous battle at Fort Wagner, and the Shaw Memorial have remained compelling subjects for artists. Poets such as Paul Laurence Dunbar and Robert Lowell praised the bravery of these soldiers, as did composer Charles Ives. Artists as diverse as Lewis Hine, Richard Benson, Carrie Mae Weems, and William Earle Williams have highlighted the importance of the 54th as a symbol of racial pride, personal sacrifice, and national resilience. These artists’ works illuminate the enduring legacy of the 54th Massachusetts in the American imagination…”

Statues & Monuments

While thousands of Civil War monuments, North and South, were erected following the war, only a handful, like the Shaw Memorial, included any recognition of the service of African Americans. In recent years, there have been new statues and monuments dedicated to African American service in the Civil War. One accounting of such statues and monuments lists more than two dozen in various locations across the U.S. According to that listing – which is an ongoing project – one or more African American Civil War monument or other tribute designation is found in the following states: Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia, and Washington, DC. And interestingly, the author of that listing has stated: “…[A]t least sixteen of these monuments were erected in the past 20 years [ i.e, from about 1991 or so]. My speculation is that this recent interest in memorializing the USCT [United States Colored Troops] got its impetus from the 1989 movie Glory.” A few random samples follow of both older and more recent African American Civil War monuments and tribute sites.

>Frankfort, KY

Interpretative plaque added to the 1924 Colored Soldiers Monument at Frankfort, KY. Click for readable version.

In July 1924, a modest Colored Soldiers Monument was dedicated at Frankfort, Kentucky’s Green Hill Cemetery. It commemorates the black soldiers from Kentucky who participated in the American Civil War. The monument is a simple 10-foot tall 4-sided limestone pillar set in a concrete base. The front bears the inscription “In Memory of the Colored Soldiers Franklin County, Kentucky Who Fought in the Civil War 1861-1865.” Inscribed around the column are the names of 142 black soldiers that hailed from central Kentucky. In later years an interpretive plaque, shown above, was added at the site telling a more complete story (click on above photo for access to enlarged copy).

>Washington, D.C.

In July 1998, a 9-foot bronze statue of African America Civil War fighters, titled “Spirit of Freedom,” along with a surrounding plaza, was dedicated in the Shaw neighborhood of Washington, D.C. ( a predominantly black area of the city named after Colonel Robert Shaw). The statue there features three black infantry men and one sailor, as well as other figures cast in relief on the back of the sculpture. The plaza is also filled with engraved lists of those who served.

“Spirit of Freedom” statue in Washington, D.C, dedicated in July 1998, honoring African Americans who served in the Civil War. Part of the inscription reads: “Civil War to Civil Rights and Beyond. This Memorial Is Dedicated to Those Who Served in The African American Units of the Union Army in the Civil War...”

Inscribed at the front base of the statue is the headline, “Civil War to Civil Rights and Beyond,” followed by the inscription: “This Memorial Is Dedicated to Those Who Served in The African American Units of the Union Army in the Civil War. The 209,145 Names Inscribed on These Walls Commemorate Those Fighters of Freedom.” Also inscribed on a granite wall at the memorial is a quote from Frederick Douglass: “Who Would Be Free Themselves Must Strike the Blow. Better Even Die Free than to Live Slaves.”( March 2, 1863). And nearby, across the street, is The African American Civil War Memorial Museum, which recognizes the contributions of the 209,145 members of the United States Colored Troops. The statue was commissioned by the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities in 1993 and dedicated on July 18, 1998. The overall site was developed by the African American Civil War Memorial Freedom Foundation and Museum. The site was transferred to the National Park Service (NPS) in October 2004.

>Vicksburg, MS

At the sprawling, 2,500-acre Vicksburg National Military Park in Mississippi, a monument to black Civil War soldiers was added in 2004. The monument consists of three bronze figures that stand atop a granite base – two black Union soldiers and a common field hand. The field hand and one soldier support between them the second soldier, who is wounded.

African American memorial commemorating the Civil War service of the 1st and 3rd Mississippi Infantry Regiments, “and all Mississippians of African descent who participated in the Vicksburg Campaign” – dedicated in February 2004, added to hundreds of other memorials at the Vicksburg National Military Park in Mississippi.

According to a National Park Service description, the wounded soldier represents the sacrifice in blood made by black soldiers on the field of battle during the Civil War. The field hand looks behind at a past of slavery, while the first soldier gazes toward a future of freedom made possible on the field of battle. The inscription on the statue’s base states: “Commemorating the service of the 1st and 3d Mississippi Infantry Regiments, African descent and all Mississippians of African descent who participated in the Vicksburg Campaign.” Mississippi provided 17,869 men to the United States Colored Troops.

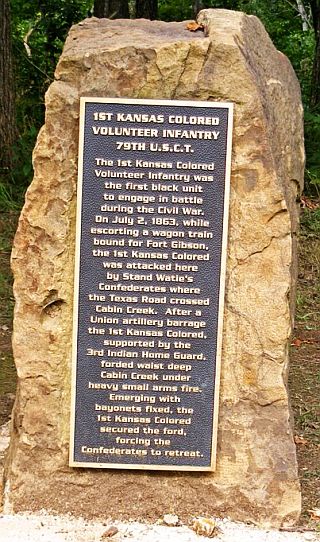

Oklahoma marker for July 1863 action by 1st Kansas Colored Infantry at Cabin Creek Battlefield near Pensacola, OK.

The park includes 1,325 historic monuments and markers, 20 miles of trenches and earthworks, a 16-mile tour road, a 12.5-mile walking trail, two antebellum homes, 144 emplaced cannons, the restored gunboat USS Cairo, and Grant’s Canal site. Since 1933, the park has been administered by the National Park Service, and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in October 1966. Over half a million visitors come the park every year.

In 1999, former Vicksburg, Mississippi Mayor Robert M. Walker, an African American, proposed placement of a monument in the Vicksburg National Military Park to recognize the contributions of African American soldiers during the Vicksburg campaign of the Civil War.

In 2000 the Mississippi House of Representatives approved funding for a monument to recognize African-American soldiers in the Civil War. With $300,000 in funding from the State of Mississippi, including $25,000 contributed by the City of Vicksburg (60 percent African American), groundbreaking for the monument was held on September 20, 2003, with dedication of the memorial on February 14, 2004.

The above samples of African American Civil War memorials and tribute sites are only a few of the existing sites, as noted in the earlier link to a longer listing. And at this writing, new memorials are also being proposed and developed.

For additional stories at this website on race and civil rights, see the Civil Rights topics page. And for film and film music, see the Film & Hollywood page.

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing and continued publication of this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 10 December 2021

Last Update: 26 March 2024

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Glory & The 54th,”

PopHistoryDig.com, December 10, 2021.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Glenn Collins, “’Glory’ Resurrects Its Black Heroes,” New York Times, March 26, 1989.

Vincent Canby, Review/Film, “Black Combat Bravery in the Civil War,” New York Times, December 14, 1989, p. C-15.

Richard Bernstein, Film, “Heroes of ‘Glory’ Fought Bigotry Before All Else,” New York Times, December 17, 1989, Section 2, p. 15.

Glenn Collins, “Denzel Washington Takes a Defiant Break From Clean-Cut Roles,” New York Times, December 28, 1989, p. C-13,

Roger Ebert, Film Review, “Glory,” RogerEbert.com, January 12, 1990.

James M. McPherson, “TNR Film Classic: ‘Glory’ (1990),” The New Republic, January 15, 1990.

“Glory (1989),” American Film Institute, AFI Catalog of Feature Films: The First 100 Years 1893–1993, AFI.com.

“Glory (1989 film),” Wikipedia.org.

“Glory (1989),” IMDB.com.

“Negroes Filled Freedom’s Ranks,“ LIFE, November 22, 1968.

“#10 – Glory (1989)”, WarMovieBuff.blogspot .com, December 3, 2013.

Movie Speech, “‘Glory’(1989): General George Strong Discusses the Strategic Importance of Fort Wagner,” AmericanRhetoric.com.

“Monument Honors Black Civil War Soldiers,” CNN.com, July 18, 1998.

Russell Duncan, Where Death and Glory Meet: Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, 1999, University of Georgia Press, 208pp. Click for copy

Gary W. Gallagher, Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollywood and Popular Art Shape What We Know about the Civil War, University of North Carolina Press, 2008. Click for copy.

“Glory,” SBIFF.org / Santa Barbara Interna-tional Film Festival.

“Fort Wagner,” Wikipedia.org.

John Smith (ed.), Black Soldiers in Blue: African American Troops in the Civil War Era, 2004, University of North Carolina Press, 478pp. Click for copy.

Valerie J. Nelson, “‘Glory’ Screenwriter Kevin Jarre Dies at 56,” Washington Post, April 23, 2011.

“The African American Soldier Memorial in Vicksburg, MS; and an Old (?) ‘Grey Curtain’/NPS Controversy,” Jubilo Emanci-pation Century.WordPress.com, March 23, 2011.

“Monuments to the United States Colored Troops (USCT) [African American Civil War Soldiers]: The List,” JubiloEmancipation Century.WordPress.com, Posted by lunchcountersitin, May 30, 2011.

Matthew W. Hughey, The White Savior Film: Content, Critics, and Consumption, Temple University Press, 2014. Click for copy.

Jeffrey Peters, Greatest Scenes, “Scene of the Week: Risking All for Glory,” NewsAndTimes .com, August 17, 2017.

Captain Luis F. Emilio, A Brave Black Regiment: The History of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1863-1865, 2017. Tells the story of the 54th after Ft. Wagner. 204 pp. Click for copy.

Geoff Boucher, “‘Glory’ At 30: Director Edward Zwick Reflects On His Civil War Epic,” Deadline.com, July 2019.

News Release, “The Shaw 54th: Restoring the Memorial and the Dialogue on Race,” National Park Service / NPS.gov, October 9, 2019.

Ella Starkman-Hynes, “Poetry Not Yet Written: Revisiting Glory Thirty Years Later,” JournalofTheCivilWarEra.org, December 10, 2019.

Joshua Meyer, “’Glory’ At 30: Denzel Wash-ington’s 1989 Breakout Film Is Still The Best Civil War Movie Ever Made,” SlashFilm .com, December 20, 2019.

Kevin M. Levin, “Why ‘Glory’ Still Resonates More Than Three Decades Later. Newly Added to Netflix, the Civil War Movie Reminds the Nation That Black Americans Fought for Their Own Emancipation,” SmithsonianMag.com, September 14, 2020.

“The Shaw Memorial,” National Park Service, NPS.gov.

“Shaw Memorial Elms,” Boston Globe/Boston Globe.com.

“The 54th Massachusetts Regiment,” National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

“Tell It with Pride: The 54th Massachusetts Regiment and Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Shaw Memorial,” NGA.gov / National Gallery of Art, Exhibit, September 15, 2013 – January 20, 2014, West Building, Main Floor, Galleries 65 and 66. (website includes audio & video resources).

“Shaw Memorial Photos,” CelebrateBoston .com.

“Black Soldiers Monument Returns to Boston Common After $3M Restoration,” NBCboston .com, March 3, 2021 (includes video on Camp Meigs historic site in town of Hyde Park, MA where 54th trained).

“United States Colored Troops,” Wikipedia .org.

“African American Civil War Memorial Museum,” Wikipedia.org.

Associated Press, Mississippi News, “Historic Projects Money Receives House Approval,” Enterprise-Journal (McComb, MS), March 24, 2000, p, 5.

Jonathan Broxton (music review), “GLORY – James Horner,” MovieMusicuk.us, February 12, 2020.

Robert Lowell, For The Union Dead, a book of poems, published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux in June 1964, with a drawing of the Shaw Memorial on its cover, and including the poem, “For The Union Dead,” inspired in part, by the Shaw memorial and the 54th. Click for copy.

Shelby Foote, The Civil War: A Narrative (three-volume history published between 1958 and 1974). Click for box set.

Geoffrey C. Ward, Ric Burns & Ken Burns, The Civil War: An Illustrated History (500+ photos), 1990, Knopf, 425 pp (companion volume to PBS TV series). Click for copy.