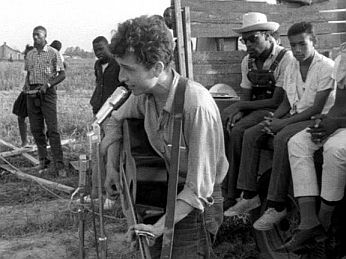

July 1963: Bob Dylan at civil rights gathering in Greenwood, Mississippi singing ‘Only a Pawn in Their Game,’ a song about the murder of activist Medgar Evers.

In the early 1960s, lunch counter sit-ins challenging “whites only” serving policies at drug stores and restaurants had received national notice after small groups of black activists in Greensboro, North Carolina and college students in Nashville, Tennessee conducted such protests in their towns. In 1961, hundreds of black and white “freedom riders” were drawn to the south to test federal requirements for desegregating interstate bus travel. By then as well, a few black students, for the first time, had gained admission to the universities of Alabama and Georgia. Blacks across the south and elsewhere were finding they could act to change their world. Medgar Evers, of Decatur, Mississippi, in his mid-30s by that time, was one of those who became committed to action.

Meanwhile, a world away in New York’s Greenwhich Village, a new, young singer named Bob Dylan had been playing coffee houses and recording new folk music along with old blues. Some of his songs would turn toward civil rights matters. More on Dylan in a moment.

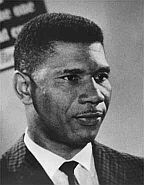

Medgar Evers, 1963.

|

“Only a Pawn A bullet from the back of a bush A South politician preaches The deputy sheriffs, the soldiers, the From the poverty shacks, he looks Today, Medgar Evers was buried from |

In early 1954, Medgar Evers applied to the then-segregated University of Mississippi to study law. When his application was rejected, Evers became the focus of an NAACP campaign to desegregate the school that would later culminate in the 1961-62 case of another student, James Meredith. By this time, Evers and his family were living in Jackson, Mississippi and he became the first field secretary of the NAACP in that state. He traveled throughout Mississippi recruiting new members, organizing voter-registration, protesting unequal social conditions, and boycotting companies that practiced discrimination. Evers soon had a high profile as an activist, and that made him a threat to the power structure in Mississippi, and also a target.

Shot in the Back

On June 12, 1963, just past midnight, Evers drove up to his Jackson home, parking under the car port, the kitchen door to his house a short distance away. Evers that night had attended a group meeting at New Jerusalem Baptist Church, while his wife Myrlie and his children watched President Kennedy’s televised speech — a speech that focused on the racial tensions in Birmingham, Alabama, where violent clashes between protesters and police had been going on for the past two months.

As Evers got out of his car, he grabbed a bundle of T-shirts that were to be handed out the next morning to civil rights demonstrators. He only took a few steps away from his car toward the kitchen door when he was shot in back. The bullet tore though his body and went into the house where his wife Myrlie and their three children were.

“Medgar was lying there on the doorstep in a pool of blood,” his wife, Myrlie, would later say. “I tried to get the children away. But they saw it all — the blood and the bullet hole that went right through him.” Medgar Evers was 37.

On June 19th, 1963 in Washington D.C., Evers was buried at the Arlington National Cemetery, receiving full military honors. More than three thousand people attended. It was the largest funeral at Arlington since the interment of John Foster Dulles, former U.S. Secretary of State in 1959.

Back in Mississippi meanwhile, on June 23rd, 1964, Byron De La Beckwith, a fertilizer salesman and member of the White Citizens’ Council and Ku Klux Klan, was arrested for Evers’ murder, but it would take decades before justice was finally served.

Two previous trials of Beckwith in 1964 had resulted in hung juries. Beckwith was then a free man, and went on to live in Tennessee until 1994, when reporting by Mississippi newspaper, The Jackson Clarion Ledger, helped bring about a new trial. The 1994 state trial, held before a jury of eight blacks and four whites, convicted Beckwith of first-degree murder for killing Medgar Evers.

New evidence in that trial included testimony that Beckwith had boasted of the murder at a Klan rally and on other occasions. His attempted appeals were denied, and more than 30 years after the murder of Medgar Evers, Beckwith began serving his life-without-parole prison term, dying in jail seven years later at the age of 80 in 2001.

“Oxford Town”

Meanwhile, back in the early 1960s, in New York’s Greenwhich Village, Bob Dylan had generated some commercial interest with his folk music and performances at local coffee houses, and had begun recording. In 1962, he released his first album, titled Bob Dylan. By then he had also written songs such as “Blowin in the Wind” and “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall,” which were labeled “protest music” by some since they touched on issues of the day, including civil rights.

Some of Dylan’s music then focused on specific civil rights controversies of that time. In 1962, for example, he wrote “Oxford Town” — a song about the riots that occurred in Oxford, Mississippi after James Meredith became the first black student to be admitted to University of Mississippi.

|

“Oxford Town” Oxford Town, Oxford Town He went down to Oxford Town Oxford Town around the bend Me and my gal, my gal’s son Oxford Town in the afternoon Oxford Town, Oxford Town |

The small town of Oxford was the university’s main campus and on September 20, 1962, it became something of battleground, as U.S. Marshalls had been sent there under direct order from President John F. Kennedy to ensure James Meredith’s enrollment and protection. Rioting ensued; two were killed and numerous students were injured. Dylan’s “Oxford Town” focused the events surrounding the campus riots and Meredith’s enrollment there, and also the larger civil rights movement then unfolding. “Oxford Town” was written by Dylan in October or November 1962 and first recorded on December 6, 1962. He is said to have performed the song at appearances in the fall and winter of 1962 and 1963, including a Carnegie Hall concert in October 1963. The song also appears on Dylan’s second album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan.

Music Player

“Oxford Town”-1962

Back in New York, Dylan continued to perform in Greenwich Village, as well other cities during 1963, and also a few television shows.

On May 12, 1963, Dylan sparked controversy when he walked out of a rehearsal for a scheduled appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. Dylan wanted to perform “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues” but was informed by CBS Television’s “head of program practices” that the song was potentially libelous to the John Birch Society. Rather than comply with the censorship, Dylan refused to appear on the program. He did perform several days later with Joan Baez on May 18, 1963 at the Monterey folk festival in California. His second album, Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan was released at the end of May 1963.

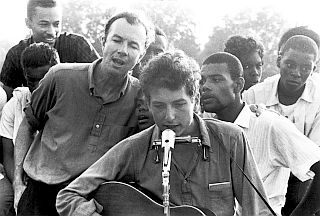

Pete Seeger performing in Greenwood, MS. Thoedore Bikel seen here adjusting mics.

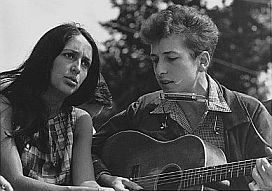

Joan Baez & Dylan in August 1963 at the historic ‘March on Washington’. Click for their separate story.

Hattie Carroll’s Death

Dylan also wrote and recorded a song in late October 1963 entitled, “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll.” The song first appeared on Dylan’s 1964 album The Times They Are A-Changin.’ However, he performed the song live very soon after he had first written it. The song provides what is believed to be a generally factual account of the death of 51 year-old African American barmaid named Hattie Carroll.

|

“The Lonesome Death William Zanzinger killed poor Hattie Carroll William Zanzinger, who at twenty-four years Hattie Carroll was a maid of the kitchen. In the courtroom of honor, the judge pounded his gavel |

Carroll was struck by a wealthy young tobacco farmer from Charles County, Maryland named William Devereux “Billy” Zantzinger — named “William Zanzinger” in Dylan’s song. For his crime, Zantzinger served a sentence of six months in a county jail. In 1963, Charles County, Maryland was still strictly segregated by race in public facilities such as restaurants, churches, theaters, doctor’s offices, buses, and the county fair. The schools of Charles County, for example, would not be integrated until 1967, four years after Hattie Carroll was killed.

Reportedly, the main incident occurred at a white-tie Spinsters’ Ball at the Emerson Hotel in Baltimore, Maryland in early February 1963. A drunken Zantzinger arrived at the hotel carrying a toy cane — a cane later described by Time magazine as “a wooden carnival cane that he had picked up somewhere.”

At the Emerson Hotel, Zantzinger assaulted at least three of the hotel workers: a bellboy, a waitress, and at about 1:30 in the morning of February 9th, barmaid Hattie Carroll. She was 51 years old, the mother of ten children. Zantzinger — then 24 years old and about 6′-2″ — struck her after she did not bring his bourbon quickly enough.

When Zantzinger and his party arrived at the hotel that night, he was already drunk and had earlier assaulted employees at a Baltimore restaurant, also using his toy cane. At the hotel Ball, however, he continued to be abusive, calling a 30-year-old waitress a “nigger” and hitting her with his cane. Shortly thereafter he started in on Hattie Carroll when she didn’t bring his bourbon immediately, cursing her — calling her a “nigger” and a ” black son of a bitch” — and hitting her on the shoulder with the cane. He also attacked his own wife, knocking her to the ground and hitting her with his shoe.

Hattie Carroll meanwhile, told co-workers she felt ill after being hit and verbally abused, and then collapsed. She was hospitalized shortly thereafter and died eight hours later. Her autopsy showed hardened arteries, an enlarged heart, and high blood pressure. A brain hemorrhage was the reported cause of death.

Zantzinger was initially charged with murder. His defense was that he had been extremely drunk and said he had no memory of the attack. His charge was reduced to manslaughter and assault, based on the likelihood that it was her stress reaction to his verbal and physical abuse that led to the intracranial bleeding, rather than blunt-force trauma from the blow that left no lasting mark. On August 28, 1963 Zantzinger was convicted of both charges and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment.

Bob Dylan at the Newport Folk Festival, 1963.

“In June, after Zantzinger’s phalanx of five topflight attorneys won a change of venue to a court in Hagerstown [50 miles or so west of Baltimore], a three-judge panel reduced the murder charge to manslaughter. Following a three-day trial, Zantzinger was found guilty. For the assault on the hotel employees: a fine of $125. For the death of Hattie Carroll: six months in jail and a fine of $500. The judges considerately deferred the start of the jail sentence until September 15, to give Zantzinger time to harvest his tobacco crop.”

Bob Dylan, meanwhile, had been following the case in the news, and reportedly wrote the song in Manhattan, sitting in an all-night cafe. He recorded it on October 23, 1963, when the trial was still relatively fresh news, and incorporated it into his live performances. Dylan also performed the song on Steve Allen’s network television program soon after its release. A studio version of the song was later released on January 13, 1964 and it also appears on Dylan’s 1964 album, The Times They are A-Changin’. But by then Dylan had begun moving away from protest and folk music.

Reluctant Icon

Dylan, with guitar, in the early 1960s somewhere in the south -- quite possibly Greenwood, MS, July 1963. Photo, www.bobdylan.com

In any case, while Dylan the musician continued to move on to new musical forms and genres — as he does to this day — his contributions to protest music remain significant and have become legend. Dylan’s protest songs of the early 1960s did make an important contribution for many in the civil rights arena and beyond. Dylan’s contributions to protest music remain significant and have become legend. “He was a folk-singer writing during a time when popular song focused on ‘Moon-June’ sentimentality and vacuous ditties,” wrote Robert Chapman in the late 1990s on why Dylan was important to civil rights in the early 1960s. “At the time it was unheard of for a young white songwriter to compose the kind of songs that he did, and he knocked down some serious barriers as to what was thought possible within the parameters of popular music.” In addition to “A Pawn in the Game,” “Oxford Town,” and “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carrol” mentioned here, other protest and civil rights-related songs he wrote include: “The Times They Are A-Changin'”, “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”, and “The Death Of Emmett Till” (a song about the a young Chicago boy beaten to death on a visit to Mississippi in 1955 for whistling at a white woman). And of course, there is also “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

Another photo of Bob Dylan and Pete Seeger at the July 1963 Greenwood, MS gathering.

“Blowin’ in the Wind,” however, was not made famous by Dylan, but by folk group Peter, Paul and Mary. Albert Grossman, who then managed Dylan, also managed Peter, Paul and Mary. Their version of the song, released as a single in 1963, sold 300,000 copies in the first week. By mid-July 1963, it was No. 2 on the Billboard pop chart and had sales exceeding one million copies. But it was Dylan’s songwriting that shone through on this and other songs of that era.

See also at this website, “Dylan’s Hard Rain, 1962-1963,” a story on the history, reaction, and various interpretations of his song, “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” For additional stories on music, see the Annals of Music category page, and for politics, the Politics & Culture page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

___________________________________

Date Posted: 13 October 2008

Last Update: 18 November 2023

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Only A Pawn in Their Game,”

PopHistoryDig.com, October 13, 2008.

________________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“Northern Folk Singers Help Out at Negro Festival in Mississippi, New York Times, July 7, 1963.

Robert Shelton, No Direction Home, Da Capo Press, 2003 reprint of 1986 original, 576 pp.

Pete Seeger, “Report from Greenwood, Mississippi: A Singing Movement,” originally published in Broadside Magazine, No. 30, August 1963; also in, Pete Seeger, The Incompleat Folksinger, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972, p. 247.

Gerry Cordon, Liverpool Community College, Book Review: Chimes of Freedom: The Politics of Bob Dylan’s Art, by Mike Marqusee New Press, 2003, Review posted, January 18, 2005.

“The Spinsters’ Ball,” Time, Friday, February 22, 1963.

“Farmer Convicted in Barmaid’s Death,” New York Times, June 28, 1963. p. 11.

“Farmer Sentenced in Barmaid’s Death,” New York Times, August 29, 1963. p. 15.

“Deferred Sentence,” Time, September 6, 1963.

Robert Chapman, writing on “African American Culture and Bob Dylan: Why He Matters,” posted to selected newsgroups, Saturday April 26, 1997, and later reprinted at “Things Twice” web page.

Bob Dylan’s website; source for “Dylan in South photo.”

“Bob Dylan” and “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” Wikipedia.org.

“Negro Applies to Enter Ole Miss,” The Jackson Daily News (Jackson, MS), January 22, 1954.

Manfred Helfert, “A Bullet from the Back of a Bush — The Life and Death of Medgar Wiley Evers,” Dignity, No. 9, Mar/Apr 1997, pp. 18-24.

Audio recording, The Story of Greenwood Mississippi, Recorded and Produced by Guy Carawan for the Student No-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Featuring Bob Moses and SNCC workers, Fanny Lou Hammer and Greenwood citizens, Mass meetings, hymns, prayers, Freedom songs, Medgar Evers and Dick Gregory, 2004 Smithsonian Folkways Recordings / 1965 Folkways Records #5593.

Murray Lerner, producer, The Other Side of the Mirror: Bob Dylan Live at Newport Folk Festival 1963-1965 (DVD), Sony, 2007.

See also a new journal devoted to Bob Dylan’s art named Montague Street and also a related blog at GardenerIsGone.

_________________________