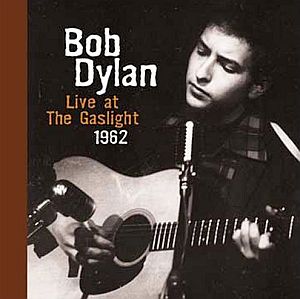

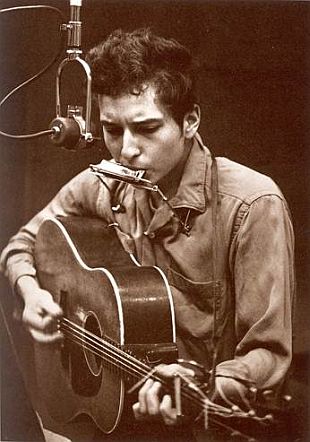

Bob Dylan at work making music and poetry in 1962.

Music Player

“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”

By late August of 1962, there had been reporting in the New York Times and Washington Post/Times Herald that the Russians had increased their military aid to Fidel Castro’s Cuba, located just 90 miles from Florida. The Russians increased the flow of conventional arms to Cuba, as the Kennedy Administration kept a wary eye on the island nation. Though not publicly revealed at the time, on August 29, 1962, a U-2 spy plane over Cuba would reveal that eight missile installations were under construction.

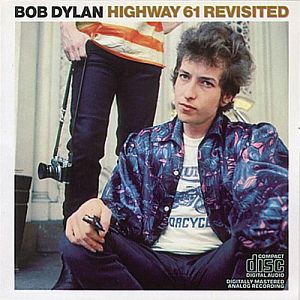

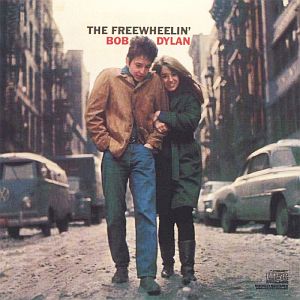

Bob Dylan, meanwhile, was in the midst of a very productive period of song writing, penning nearly 40 songs in 1962. One of these was “A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall,” which Dylan appears to have written sometime that summer, possibly influenced by the gathering storm clouds over Cuba. The song would become a classic protest song, one filled with forebodings on war, social injustice, and other dreads. Dylan first performed the song in September at the Gaslight Café in Greenwich Village, and then more publicly a week or so later on September 22nd at Carnegie Hall as part of a hootenanny show sponsored by Sing Out magazine. Dylan by then had also been working in studio sessions with his recording label, Columbia Records, which would record “Hard Rain” as part of his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, not released for sale until late May 1963.

Dylan patterned “A Hard Rain…” after a British folk ballad, “Lord Randall,” Child Ballad No. 12, from the late 19th century, in which a mother repeatedly questions her son, beginning with “Where have you been?,” as the ballad later reveals the son has been poisoned and dies. Dylan’s “Hard Rain” embraces a broad message with themes and imagery relevant to injustice, suffering, pollution and warfare – a song well-suited for its times and beyond.

|

“A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall” Oh, where have you been, my blue-eyed son? Oh, what did you see, my blue eyed son? And what did you hear, my blue-eyed son? Oh, who did you meet my blue-eyed son? And what’ll you do now, my blue-eyed son? |

By October 1962, the “Cuban missile crisis,” as it came to be called, had the full attention of a nervous nation. The young Presidency of John F. Kennedy was brought to the brink of war in a showdown with Russia. On October 16th, Kennedy was shown new U-2 photos revealing fully-equipped missile bases in Cuba capable of attacking the U.S. with nuclear warheads. Plans were drawn up for a possible U.S. invasion of Cuba, as a massive mobilization of military personnel and hardware began. Troops and equipment were assembled in Florida.

JFK on TV

President Kennedy appeared on television to inform Americans of the crisis and the possibility of a confrontation. A Naval blockade was placed around Cuba to prevent the Russians from delivering more missiles.

In the end, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev turned his ships around, averting what some believe could have become World War III. The Soviets agreed to dismantle the missile sites and the U.S. agreed not to invade Cuba. The crisis was the closest the world ever came to nuclear war in the 1960s.

Dylan’s Fears

Bob Dylan no doubt, like the rest of the country at the time, wasn’t sure what those days might bring. In the liner notes on Dylan’s Freewheelin’ album of May 1963, music writer Nat Hentoff would reveal that Dylan wrote “A Hard Rain” under some dread at the time – certainly in the shadow of Cold War tensions generally, whether or not the summer-of-1962 events on Cuba were the spur for the song:

“Every line in it [i.e. ‘Hard Rain’] is actually the start of a whole new song,” Dylan told Hentoff. “But when I wrote it, I thought I wouldn’t have enough time alive to write all those songs so I put all I could into this one.”

Certainly in the aftermath of the Cuban missile crisis, as the nation had faced the possibility of a nuclear exchange, Dylan’s “Hard Rain” dread – and similar songs that would arrive with his Freewheelin album, including “Blowin in the Wind,” and “Masters of War” – gave Dylan a kind of philosophical currency he did not have before.

But Dylan did add some clarification when it was suggested that the refrain of “Hard Rain” was meant to convey nuclear fallout. In a 1963 radio interview with Studs Terkel, Dylan stated: “No, it’s not atomic rain, it’s just a hard rain. It isn’t the fallout rain. I mean some sort of end that’s just gotta happen… In the last verse, when I say, ‘the pellets of poison are flooding the waters’, that means all the lies that people get told on their radios and in their newspapers.”

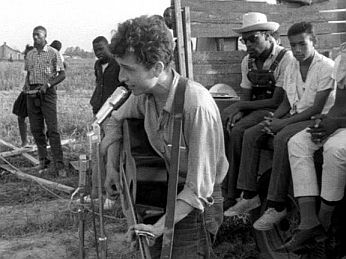

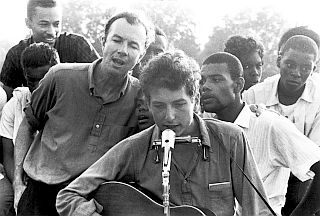

Early 1960s: Bob Dylan performing and/or recording.

“A Hard Rain,” said one review in Rolling Stone, “is the first public instance of Dylan grappling with the End of Days, a topic that would come to dominate his work.” The verses, continued that review, are examples of Dylan describing his task as an artist: “to sing out against darkness wherever he sees it.” Bob Weir of the 1960s’ Grateful Dead rock group said of the song: “It’s beyond genius… I think the heavens opened and something channeled through him.”

“The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan” album, released in May 1963, included “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” Click for CD.

Dylan himself writes about that period of his life in his book, Chronicles, where he explains that he was then reading a lot about the pre-Civil War period at the New York Public Library, and finding little to be cheery about. That, no doubt, coupled with the angst of his own times, pushed the artist to his own inner revelations and the poetry he then produced. Dylan was 21 years old in 1962, with a lot more ahead.

|

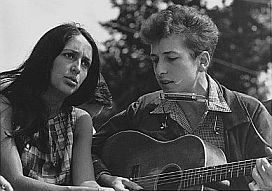

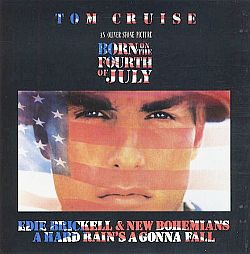

“What Does It Mean?”  Bob Dylan in Washington, D.C., August 1963. …The “white ladder all covered with water” could refer to the popular capitalist myth of the ladder of success that everyone is supposed to be able to climb if only they work hard enough, blah blah yadda yadda. Only some people may be so poor and beaten down that they cannot climb the ladder… For them the ladder is symbolically “covered with water” and no matter how hard they try to climb it they just keep slipping down…. Tim, of Charlotte, North Carolina, offers his view on another “Hard Rain” line: “‘I saw a black branch with blood that kept drippin’– I always thought this was a reference to the Billie Holiday song ‘Strange Fruit,’ which referred to the lynchings of black people in the South…” Bob of Boston has a different take on the same line:With Dylan’s work, like all poetry, “there are a myriad interpretations…” “I believe the line ‘I saw a black branch with blood that kept drippin’ is a reference to Dante’s Inferno where a group of sinners are doomed for eternity to be trapped in black trees. When Dante breaks one of the branches the tree bleeds and cries out…” “This song is, indeed, about the threat of nuclear annihilation,”writes James of Wakefield, Massachusetts, citing the line, “the roar of a wave that could drown the whole world.” But James also adds: “that is far too simplistic an analysis. Bob Dylan’s work is as close as popular music ever came to approaching real poetry and, like all poetry, there are a myriad interpretations. Some of the themes addressed in this work include the general injustice of the world, the unrealized ‘better society’ (‘a highway of diamonds with nobody on it’), the guilt and fear in leaving a dangerous and damaged world to the next generation (‘I saw a new-born baby with wild wolves all around it’),…the artist’s fear of ‘shouting in the wilderness,’ and so on…”  MCA single of “A Hard Rain's A Gonna Fall” by Edie Brickell & New Bohemians from 1989 film, “Born on The Fourth of July.” Meanwhile, another of the “Hard Rain” interpreters suggested that the highway-of-diamonds line “referred to the carbon in asphalt converted to diamonds under intense (nuclear) heat.” Amanda, from Fayetteville, Arkansas wrote: “I believe the line about the woman whose body was burning is in reference to Joan of Arc, and the young girl who gave him a rainbow is Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz. Just my opinion.” And Mark from Washington, D.C. called Dylan “an empath, channeling the late 50’s and early 60’s mood and culture into lyrics.” These, of course, are only a small sampling of opinion and interpretation on Dylan’s song from various sources. |

Cover art for Bob Dylan’s 2008 version of “a Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall,” produced for Expo Zaragoza.

Dylan also chose a local-band, Amaral, to record a version of the song in Spanish. The new version of “Hard Rain” ended with a brief Dylan comment that he was “proud to be a part of the mission to make water safe and clean…”

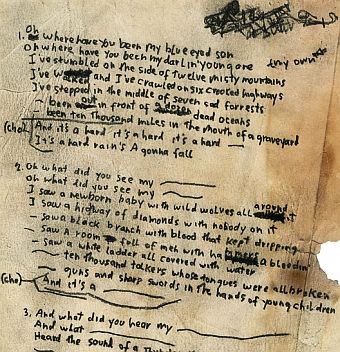

Handwritten Lyrics

A portion of the page of Bob Dylan’s handwritten lyrics for the song “A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall,” that reportedly sold at auction in August 2009 for $51,363.60. Click for auction site.

Since then, additional handwritten lyrics of Dylan’s have gone to the auction block, with collectors bidding even higher amounts. Dylan‘s handwritten lyrics to “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” with most of the verses appearing on a weathered sheet of ruled paper — which also included Dylan’s lyrics for “North Country Blues” on the back — sold at an auction for $422,500, according to a Sotheby’s representative. The winning bidder in this case was Adam Sender, identified as an American collector and a hedge fund trader. Mr. Sender also owns the guitar that John Lennon was using when he met Paul McCartney. Sotheby’s was “banking on there being a rich person out there who came of age in the 1960s for whom this [Dylan’s lyrics] would mean a great deal,” said Sean Wilentz, a history professor at Princeton University and author of Bob Dylan in America.

2005: Paperback edition of Bob Dylan’s memoir, “Chronicles,” Vol. 1, published by Simon & Schuster. Click for book.

Bob Dylan’s musical cannon, meanwhile, continues to be heard and played around the world. To date, his “Hard Rain,” for example, has more than two dozen cover versions, including those by Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, Leon Russell, Bryan Ferry, Robert Plant, Jimmy Cliff, and others. As a songwriter and musician, Dylan has received numerous awards over the years including Grammy, Golden Globe, and Academy Awards; he has also been inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame. He is considered to be one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century and has produced 34 studio albums, 13 live albums, and 14 compilation albums. Seven of his albums were No. 1 hits on the U.K. album charts; five topped the charts in U.S. In 2008, the Pulitzer Prize jury awarded him a special citation for “his profound impact on popular music and American culture, marked by lyrical compositions of extraordinary poetic power.”

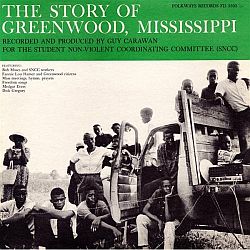

See also at this website, “…Only A Pawn in Their Game,”another story of Dylan’s protest music from the early 1960s. Additional stories on music at this website may be found at the “Annals of Music” category page, or go to the Home Page for other story choices. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing, and continued publication of this website. Thank you. — Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 6 March 2012

Last Update: 19 June 2023

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/PopHistoryDig

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Dylan’s Hard Rain, 1962-1963,”

PopHistoryDig.com, March 6, 2012.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“Bob Dylan,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, New York: Rolling Stone Press, 3rd Edition, 2001, pp.286-288.

Alan Light, “Bob Dylan,” in Anthony DeCurtis and James Henke (eds), The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock n Roll, New York: Random House, 1992, pp.299-308.

Bob Dylan, Writings and Drawings by Bob Dylan, New York: Borozi/Alfred A Knopf, 1973.

“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” Wikipedia .org.

Associated Press, “Cuba Charges U.S. With Air Violations,” Washington Post, Times Herald, July 2, 1962, p. B-19.

“Raul Castro Sees Khrushchev,” Washington Post, Times Herald, July 4, 1962, p. A-8.

“Experts Doubt Landing Of Red Forces in Cuba,” The Washington Post, Times Herald, August 9, 1962, p. A-17.

“Cuba Says Sub Violated Waters; U.S. Denies It,” Washington Post, Times Herald, August 16, 1962, p. A-16.

“Red Technicians Landing in Cuba,” Washington Post, Times Herald, August 17, 1962, p. A-1.

“U.S. Studying Red Influx in Cuba,” Washington Post, Times Herald, August 23, 1962, A-17.

“15 Communist Ships Head for Cuba, Probably With Arms, Technicians,” Washington Post, Times Herald, August 24, 1962, p. A-8.

“Guns to Cuba,” Washington Post, Times Herald, August 24, 1962, p. A-12.

Joseph A. Loftus, “Russians Step Up Flow of Arms Aid to Castro Regime; More Technical Personnel Sent In–U.S. Aides Doubt Rise in Offensive Power; Soviet Increases Aid Flow to Cuba,” New York Times, August 25, 1962, p. 1.

Robert Shelton, “Songs a Weapon in Rights Battle; Vital New Ballads Buoy Negro Spirits Across the South; Music Is New Force in Bolstering Morale, Leaders Declare,” New York Times, August 20, 1962, p. 1.

“Carnegie Is Still Going Strong: Capacity Crowd at Hootenanny,” New York Times, September 24, 1962.

“The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan,” Wikipedia .org.

“The Ten Greatest Bob Dylan Songs,” Rolling Stone.com.

Greil Marcus, Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads, Public Affairs, 2005.

Song List & Liner Notes by Nat Hentoff, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, May 1963.

Teri Tynes, “New York Notes on Bob Dylan’s ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’,” Walking Off The Big Apple, March 31, 2010.

“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall by Bob Dylan,” SongFacts.com.

Evan Schlansky, “The 30 Greatest Bob Dylan Songs: #7, ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’,” American Songwriter.com, May 1, 2009.

Bob Dylan, Chronicles: Volume One, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004, Paperback, 2005.

Mark Edwards, Lloyd Timberlake, Bob Dylan, Hard Rain: Our Headlong Collision with Nature, Publisher: Still Pictures Moving Words, 2006.

“Born on the Fourth of July (film),” Wiki- pedia.org.

Lot #171: Bob Dylan “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” Handwritten Working Lyrics, GottaHaveRockandRoll, Bidding ended on: August 6, 2009.

Dave Itzkoff, “Sign of the `Times’: Dylan’s Lyrics for Sale,”Arts Beat, New York Times, November 29, 2010.

“Bob Dylan’s Handwritten Lyrics on View in NYC,” The Independent (UK), December 4, 2010.

Dave Itzkoff, “Accept It: Dylan’s Lyrics Are Sold at Auction,”Arts Beat, New York Times, December 10, 2010.

“Bob Dylan’s Handwritten ‘Times They Are a-Changin” Lyrics Sell for $422,500; Hedge-Fund Trader Buys Document at Sotheby’s Auction,” Rolling Stone, December 10, 2010.

Katya Kazakina, “Dylan’s ‘Times They Are A-Changin’ Fetches $422,500,” Bloom- berg.com, December 10, 2010.

See also a new journal devoted to Bob Dylan’s art named Montague Street and also a related blog at GardenerIsGone.

_____________________________