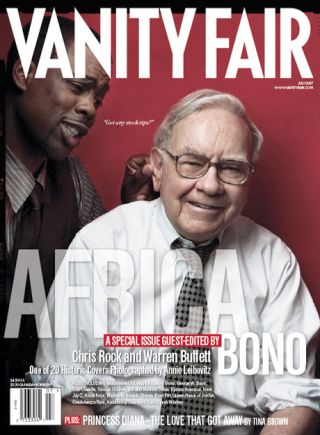

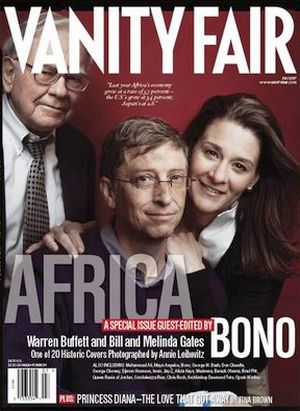

Warren Buffett was one of 20 Annie Leibovitz-photographed celebrities featured on a series of covers for a special issue of ‘Vanity Fair’ for July 2007 focused on Africa. Here Chris Rock is asking, ‘Got any good tips?’ Click for copy.

Although Buffett was a well-known figure and even famous in the business community dating to the 1960s, he was not generally known elsewhere outside of that community. Even through the 1970s and 1980s, Buffett was not the economic “rock star” he would later become.

In recent years, however, Warren Buffett has “crossed over” from purely business stardom to more full-blown, mainstream celebrity. It’s not clear precisely when this arrival occurred, but the process began in the 1980s, especially as his name rose into the upper reaches of the Forbes 400 “richest Americans” list.

Then, in the mid-1990s, a popular book on Buffett’s investing method — The Warren Buffett Way, by Robert Hagstrom — became a national bestseller, raising Buffett’s visibility among millions of existing and would-be investors.

By 2003, prime-time “Buffet celebrity” grew to a much higher level, reaching a crescendo of sorts in mid-summer 2006 after he announced plans to give away most of his wealth through a series of donations — the biggest share of which would go to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. More on that later.

Warren Buffett on the September 7, 2008 cover of "Parade" magazine, the wide-circulation Sunday newspaper magazine that goes to millions of American homes. Click for copy.

Mr. Buffett’s rising celebrity, however, has not yet made him a Saturday Night Live host, but he has made cameos in a TV soap opera, and in 2008 he began making a cartoon series for kids to help teach them about money. Buffett has also appeared on countless business magazine covers, as well as avant garde publications such as Vanity Fair’s special-edition Africa issue of June 2007 (above and below) which featured various combinations of Annie Leibovitz-photographed celebrities on some 20 different covers.

Another in the sequence of Vanity Fair's July 2007 covers, this one with Buffett and Bill and Melinda Gates. Click for copy.

Nor has Warren Buffett lived most of his life in prime-time media country, or for that matter, prime-time Wall Street. Buffet chose to live much of his life in mid-America: Omaha, Nebraska. This was largely by self design; wanting to live a quiet, average, if-not-frugal life style in Omaha where he could devote his attention to investing — at least a first.

But as more attention came to his investment savvy and his growing wealth, so did more popular notice. In fact, the world, or at least a portion of its investors, was soon beating a path to Omaha to hear the master’s voice.

Still, Buffett’s celebrity came slowly at first, rising with his “oracle” and “wealthiest American” stature. By the late 1990s he had begun to permeate the mainstream press and media — first on the covers of business magazines and business-related cable television, and later, more widely throughout the mainstream press and network television. Certainly by the 2000s, Warren Buffett was famous simply because he was “Warren Buffett.”

Part of the business & financial press that became commonplace for Warren Buffett in the 2000s --the November 2006 cover of the Wall Street Journal's "Smart Money" magazine. Click for copy.

True, Buffett’s popular notice is, on one level, no different than that of other wealthy business barons from other eras — Andrew Carnegie, Henry Ford, John D. Rockefeller, and others who rose to fame and infamy in their day.

Yet Buffett’s rise has its unique aspects — rising to wealth as an investor rather than industrial mogul, for one. And his popular notice has been aided certainly by today’s “always-on-everywhere” mainstream and digital media.

But Buffett’s story also shows that once he arrived in the media glare, he moved to use his fame — and the media machine that comes with it — to reach a broader audience on a few selected social and economic issues of concern to him, pushing his message and lobbying for changes as he saw fit. And certainly with his recent philanthropy, Warren Buffett has spoken in a way few people ever can.

Business Boy

Warren Buffett was born in Omaha in 1930. He began selling things as a young boy — Juicy Fruit gum, Coca-Cola, Liberty magazine, the Saturday Evening Post, and even used golf balls. In the mid-1930’s, at about age 6, he started buying six-packs of Coke for 25 cents and reselling single bottles at a nickel each. He also worked at his grandfather’s grocery store. At age 11 he had made his first stock investments and also announced that he would be a millionaire by the time he was 35. At around age 10 or so he concluded that money could give a person independence, and thereby, the means to do whatever he wanted with his life. So, at age 11 he announced he would be a millionaire by 35.

Buffet’s father was a stockbroker, and young Warren often visited his office, sometimes chalking in stock prices on the brokerage’s blackboard. At age 11 he made his first stock investment — three shares of Cities Service oil company at $38 per share. The stock dropped to $27, but the young Buffett held his marks, selling only when they reached $40 a share. Later, Cities Services’ shares rose to nearly $200 a share, leaving Buffett with an early lesson in patient investing that he never forgot. By age 13, Buffett was running his own businesses as a paperboy and also selling his own horse-racing tip sheet. On his first tax return that year, he claimed his bike as a tax deduction.

In 1942, Buffett’s father was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, the family moved to Fredricksburg, Virginia near Washington. Buffett attended high school in Washington but also worked at side businesses. When Buffett received his college degree at age 20, his side businesses had earned nearly $10,000. With a friend he purchased a used pinball machine for $25, installed it in a barbershop and within a few months they had made enough money to buy and install two more machines at other locations, then selling their little business for $1,200. At age 16, Buffett reluctantly enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania to study business, but after two years, moved to the University of Nebraska. It was at Nebraska where he discovered a book by Benjamin Graham titled the The Intelligent Investor, which taught the importance of “value investing” — going after undervalued stocks with good names and holding them for long periods, as opposed to running after the “hot stock ” of the day. By the time Buffett finished his degree at age 20, his side businesses had earned him nearly $10,000. Buffet next went to Columbia University for an advanced degree after being turned down at Harvard Business School. At Columbia he studied under his idol Benjamin Graham, and would later work with him in New York for a couple of years and also at his father’s brokerage back in Omaha.

|

“The Investable Float” One of Buffett’s early epiphanies about how to use other people’s money to make millions for himself and his investors, came with his introduction to the insurance indus- try. Sometime in the 1950s he noticed that his mentor, Benjamin Graham held lots of stock in an insurance company named GEICO — where Graham would also serve as chairman. Buffett decided to visit GEICO’s offices one weekend, and by chance happened upon a rising officer of the company who pro- ceeded to give him a crash course on insurance. Buffet learned about GEICO’s nice little corner of the insurance world, where it sold insurance to a group of statistically safe drivers — govern- ment employees — and sold to them direct by mail. By doing so, it cut out agent commissions and made low-priced policies possible, while the pool of generally safe drivers it selected kept claims and pay outs low. But the big thing that Buffett learned about the insurance industry that day, and GEICO in particular, was the horde of ready cash that insurance companies could gener- ate. Lots of liquid cash coming in from premiums that was not needed to cover a low outlay of costs for claims. This was big-time money — “the float,” the difference between money in and demand on money out; money that could be used for other things, like investing. The benefits of the insurance company “float” were real and could translate into buying leverage and big profits for a studious investor. Buffett, then still in graduate school, invested a portion of his savings in GEICO. And throughout his investing career thereafter, insurance companies would become a key part of his investment strategy, making minimal profits on insurance underwriting, but using the “insurance company float” to leverage hundreds of millions for other investments and continuing profits elsewhere. |

First Partnership

In 1956, with the money of a few investors and some of his own, he formed the Buffett Partnership in his hometown of Omaha. He began purchasing stocks with the goal of beating the Dow Jones Industrial Average by 10 percent a year — and he proceeded to do just that. His investment success was fueled in part buying undervalued companies whose stocks steadily rose. By 1962, the Buffett Partnership, which began with $105,000, rose in worth to $7.2 million, about $1 million of which was owned by Buffett and his wife, Susie. But their assets continued to grow.

Buffett would typically buy when others were running for the exits. In 1964 when American Express shares fell to $35 due to a fraud scandal and everybody was selling, Buffett began buying the shares en masse. A year later AmEx shares were selling for double the price he paid for them. In 1965, after a personal meeting with Walt Disney, Buffett bought $4 million worth of the Disney Co., then equal to about five percent of the company. Buffett by this time was being noticed in the financial and investment communities. In March 1966, Buffett explained his firm’s strategy to the New York Times, saying: “We have no formal program of acquisitions, but as a private investment partnership, we like to put our money into things with good value and good management.” The Buffett Partnership ended in 1969. It had been wildly successful making about 30 percent gains year-over-year between 1956 to 1969. This in a market in which 7- to-11 percent gains were the norm. With his first venture a success, Buffett began forming a new investment vehicle.

In 1962, he began acquiring shares of Berkshire Hathaway, a textile mill in New Bedford, MA. As the U.S. textile industry withered in the face of foreign competition, Buffett began redeploying Berkshire’s capital into an array of other businesses, including insurance. He bought his first insurance companies in 1967, learning how to use their up-front cash flow and “float” (see sidebar at right) to make other, longer-term growth investments. Insurance companies would become a key part of Buffett’s businesses and investment strategy throughout his career. He would eventually sell off the textile portion of Berkshire Hathaway, but use the company structure as his investment vehicle. By 1970 at age 40, Warren Buffett was chairman of Berkshire Hathaway.

Through the 1970s he continued pursuing the same investment strategy that had made him a millionaire in the 1960s. When stock prices began to drop in 1973, Buffett became a buyer for the long term. In 1973, one of the stocks Berkshire began acquiring was The Washington Post Co. Throughout the 1970s, Buffett’s name would surface on the business pages of regional and sometimes national newspapers. “Buffett Is Said to Take Stake of 10-15% in GEICO,” read the New York Times headline on August 13, 1976. That short story — about Buffet’s investment in the insurance business — ran in the back pages of the newspaper, but noted that Buffett had “a reputation as one of the country’s most astute investors.”

In 1977, Berkshire indirectly purchased the Buffalo Evening News for $32.5 million. About this time, he and his wife / business partner, Susie, began living apart, though remaining married. Susie, in fact, introduced him to Astrid Menks, a woman who worked in Omaha and who would eventually move in with Buffett and later become his second wife. By 1979, Berkshire continued buying up stocks it regarded as values, then beginning to buy shares of the ABC television network, among others. Berkshire shares about this time were trading at $290 each. Buffett’s personal wealth was then about $140 million, although he was only taking an annual, modest salary of $50,000.

First Forbes List

In 1982, Forbes magazine began publishing its annual “Forbes 400” — the 400 richest people in America. Daniel Ludwig, a shipping magnate, was then the richest person on the list at $2 billion. Warren Buffett also made that first list, at an estimated $250 million in wealth. Although not then in the top reaches of the list in 1982, Buffett was just beginning his rise into the upper tiers of the super rich.

In fact, in 1983, Berkshire Hathaway shares had begun the year at $775 per share, but by year’s end they were worth at $1,310 per share. Buffett’s personal net worth at this point is $620 million. Berkshire now had some $1.3 billion in its corporate stock portfolio. It was making money buying up lesser known but solid companies such as Blue Chip Stamps and Nebraska Furniture Mart, the latter for $60 million in 1983. But by 1985, Buffett became a key player in some more well known businesses, helping to bring about a merger between ABC and Cap Cities, a major media play. Then in 1987, Buffett got Wall Street’s attention when Berkshire Hathaway purchased 12 percent stake in Salomon Brothers investment bank, making Berkshire the largest single shareholder and Buffett the director. Berkshire’s $700 million stake in Salomon helped rescue it from corporate raider Ronald Perelman. (Buffett would return to Salomon in 1990, after a scandal erupted there over trading rules, with Buffett coming in to run the company for a time after top management resigned. The company was eventually sold). Buffet’s name by this time also was appearing regularly in the business press. In October 1987, when the stock market crashed, Buffett and Berkshire took big hits, but both would recover.

|

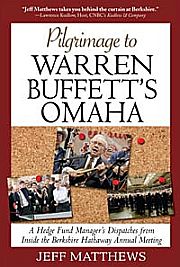

“Warren’s Woodstock”  The Berkshire Hathaway annual meetings in Omaha, NE, once a “drop-by-for-dinner” affair of a few dozen, are now attended by 30,000 or more. For some years now, Buffett has also drawn national press attention for his unique writing in the annual Berkshire Hathaway “letter” he sends to his stockholders, noted for its uncorporate style. Buffett’s annual Berkshire letter, in fact, has become something of a business literary event, praised for its colorful and pithy style, while also revealing something of Buffett’s “aw shucks, dumb-as-a-fox” media savvy. |

“…Better With Coke”

Warren Buffett made some of his first profits with Coke as a kid and later in life as one of the company’s biggest investors. Click for Coke history.

“We like businesses we understand,” Buffett told the New York Times. “Coke is like Mom and apple pie.” And with companies like Coke, he explained, “our favorite holding period is forever.” Buffett also explained that Berkshire didn’t buy companies they didn’t understand. “We buy very few things but we buy very big positions,” he said. In addition to Coke, Berkshire also then held about 12 percent of Salomon Inc., the Wall Street investment firm; 42 percent of GEICO insurance, 18 percent of Capital Cities/ABC Inc., the broadcasting and publishing company; and 13 percent of the Washington Post Company. Buffett said at the time these were among Berkshire’s ”permanent” common stock holdings — those the company would hold for a long time. “We like businesses we understand,” Buffett told the New York Times. “Coke is like Mom and apple pie.” And with com- panies like Coke, he said, “our favorite holding period is forever.” By the end of 1989, Coca Cola represented 35 percent of Berkshire common stock portfolio. It was a bold move. But with time, Coke would prove to be one of Berkshire’s most lucrative investments, turning a $1 billion purchase into a $10 billion holding that would also generate more than $250,000 a year in dividends.

Another standard mainstream company Buffett would invest in during the late 1980s was the razor blade maker Gillette. “It’s pleasant to go to bed every night knowing there are 2.5 billion males in the world who have to shave in the morning,” Buffett would later tell a Forbes reporter. “A lot of the world is using the same blade King Gillette invented almost 100 years ago. These nations are upscaling the blade. So the dollars spent on Gillette products will go up.” Buffet also noted in answer to a question about why he did not invest in foreign stocks: “I get $150 million earnings pass-through from the international operations of Gillette and Coca Cola. That’s my international portfolio.”

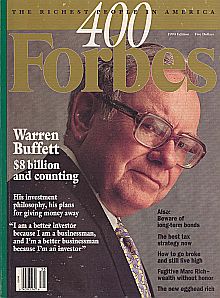

Warren Buffett on the cover of the October 16, 1993 issue of ‘Forbes’ magazine, which ranked him No.1on the ‘Forbes 400 Richest Americans’ list.

1990s: Rising Notice

In the 1990s, Warren Buffett began to become more visible in the mainstream business press and other media. In October 1993, for example, he was now featured on the cover of the annual “Forbes 400” issue.

“Warren Buffett — $8 Billion and Counting,” said the cover’s tag line. Buffett was then No.1 on the Forbes list worth an estimated $8.3 billion, besting other financial superstars such as fellow billionaires Bill Gates of Microsoft ($6.1 billion), John Kluge of Metromeida ($5.9 billion), Sumner Redstone of Viacom ($5.6 billion), and five Walton family members of Wal-Mart wealth ($23 billion together).

Buffett reported to Forbes at the time that he was very happy with his life, coming across to writer Robert Lenzner as a guy who didn’t need to rub shoulders with celebrities — or be one himself. Buffett had then received an invitation from his Washington Post friend Kay Graham to dine with her and President Bill Clinton on Martha’s Vineyard in the summer of 1993, but Buffet turned it down. “I have in life all I want right here,” he told Lenzner who came to Omaha for the interview. “I love every day. I mean, I tap dance in here and work with nothing but people I like. I don’t have to work with people I don’t like.”

|

“When Warren Met Bill” Warren Buffett and Bill Gates met for the first time during the July 4th holiday of 1991. Bill Gates, the 35 year-old founder and CEO of Microsoft, the world’s largest computer software company, was then ranked at No. 38 on the 1990 Forbes list of the world’s billionaires, with Gates’ estimated worth then placed at $2.5 billion. Warren Buffett then ranked higher on that list at No. 32 with a net worth at $3.8 billion.  Warren Buffett.  Bill Gates. “We talked and talked and talked and talked and paid no attention to anybody else,” recalled Gates. “I started asking him a whole bunch of questions about his business, not expecting to understand any of it. He’s a great teacher, and we couldn’t stop talking.” Buffett recalled that Gates tried to convince him to get a computer. and even agreed to send someone to teach him how to use it. Buffet declined, not sure how he would make good use of it saying he wasn’t the kind who incessantly had to check his stocks, and that he did his income taxes in his head. In any case, a fast friendship was in the making. By the time they reached the dinner table, Bill Gates, Sr. put a questioned to his guests: What factor did people feel was the most important in getting to where they were in life? Both Buffett and Bill Gates said “focus.” Later, as the helicopter departed, Gates was not on it. |

Warren’s Way

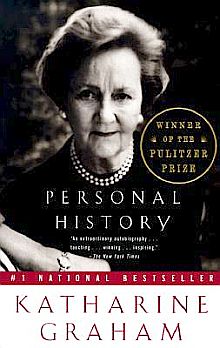

Robert Hagstrom's best-selling 1994 book on Warren Buffett's investing methods also helped to raise the public visibility of Buffett. Click for book.

|

“Disney, Buffett & ABC” In 1995, Warren Buffett was attending the annual gathering of business and media moguls in Sun Valley, Idaho — a gathering of the rich and powerful for schmoozing, seminars, and sharing ideas in a relaxed setting. Michael Eisner, then chairman of the Walt Disney Company, was there, as well as a number of other Hollywood and media notables. In one talk about his company, Eisner used a letter he had received from Warren Buffett two years earlier to drive home a point about Disney’s rising value. In 1993 Buffett had written Eisner explaining: “In 1965, I bought 5 percent of Disney for approximately 4 million dollars. That’s the good news. The bad news is that I sold it two years later [1967] at about a $2 million profit.” Eisner then explained that he couldn’t resist replying to Buffett — rubbing salt in the wound, more or less — that if Buffett had held his position in Disney through 1993, it would have been worth $552 million. “Since Warren is here today,” continued Eisner in his Sun Valley talk, “I just thought I’d bring him up to date. If he had held on to that original investment over all these years, today his $4 million would be worth $869 million.” But Eisner was quick to tell his audience they shouldn’t feel too badly for Buffett, adding: “If Disney had purchased $4 million worth of Warren’s Berkshire Hathaway stock in 1965…it would be worth in excess of $6 billion today.”Warren Buffett, meanwhile, would get another shot at Disney — though this time from a different direction — with the deal-making occurring right there in Sun Valley shortly after Eisner had given his talk. More on that in a moment; first a little background. In 1979, Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway began to acquire stock in the ABC television network, adding to and holding those shares for the next several years. In March 1985, a company named Capital Cities Communications made a surprising $3.5 billion acquisition of ABC, a stunning media buy as ABC was then some four times bigger than Capital Cities. Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway, it turned out, helped finance the deal. In return, Buffett and Berkshire got a 25 percent stake in the new Cap Cities/ABC colossus, then one of the biggest media concerns on the scene. Buffett, it would turn out, would be right in the middle of some of the biggest media deals of the 1980s and 1990s — and making a few bucks in the process. In 1995, by the time Warren Buffett and Michael Eisner and others were convening at the Sun Valley media fest, Warren Buffett owned 13 percent of Capital Cities/ABC. After Eisner finished his Sun Valley talk, he happened to run into Warren Buffett in the parking lot. The conversation between the two turned to some current media mergers then in play, as Disney was then considering a move to acquire the CBS television network, also being sought by the Westinghouse Corporation. But then Eisner, of Disney, said to Buffett — “…Unless, of course, you want to sell us Cap Cities [and ABC] for cash.” To Eisner’s surprise, Buffett responded, “sounds good to me,” who then suggested they both go talk to Tom Murphy about it. Murphy was head of Cap Cities and Buffett at that moment happened to be on his way to meet him and Bill Gates of Microsoft. “I’m just going to meet him,” Buffet told Eisner. “We have a date to play golf with Bill Gates. Why don’t you walk over with me.” Eisner walked along with Buffett and upon meeting Murphy, Buffett made introduction: “Michael wants to pay cash for Cap Cities,” said Buffett to Murphy. “I think he’s right. Any time we ever bought anything at Berkshire that worked out, it was in cash. What do you think, Tom?” Eisner recalled that Murphy then seemed taken aback by Buffett’s direct manner on such a major deal. “…Here we were, standing together in a parking lot in the middle of Idaho, talking about a $20 billion transaction.” After Eisner and Murphy later returned to their offices, they began a series of telephone calls and negotiations, essentially agreeing to a deal after some days of back and forth — and without lots of middle men and lawyers involved. The deal made eminent sense to Buffett–merging the No.1 content company, Disney, with the No.1 distribution company, Cap Cities / ABC. Although at first, Eisner and Disney were still nominally in the running to acquire CBS — and Eisner used that as a point of leverage in his talks with Murphy — CBS would be bought by Westinghouse. Disney then made the deal with Cap Cities/ABC — at $19 billion; then the second largest acquisition in corporate history. Warren Buffett, as a Cap Cities director, was a major influence on Cap Cities’ decision to accept Disney’s bid. And Buffett was a very happy camper by the time the deal closed in New York. Berkshire’s 20 million shares of Cap Cites fetched a pre-tax return in the neighborhood of $2.1 billion. Buffett took his payment in all Disney stock rather than cash, showing his and Berkshire’s confidence in Disney. Buffett had also been buying up additional Disney shares. At the news conference in New York announcing the deal, Buffett, then 64, sat on the dais with Disney Chairman Michael Eisner and Cap Cities/ABC Chairman Thomas Murphy. Eisner repeatedly referred to how much Warren Buffett approved of the deal. Buffett, for his part, added: “This deal makes more sense than any other deal I have seen except for the [1986] Cap Cities and ABC deal. It is a merger of the No. 1 content company [Disney] with the No. 1 distribution company [ABC].” |

The Buffett Millionaires

Further enhancing the “pop persona” bona fides of Warren Buffett, were the national press stories that began appearing in the mid-and late-1990s of average people who became fabulously rich courtesy of “Warren’s Way.” In May 1997, for example, the story of Rabbi Myer Kripke and his wife Dorothy appeared. The Kripke’s, who had become friends to Buffett in the 1960s, gave him a $65,000 inheritance at that time to invest. By 1996, Buffet had turned that $65,000 into $25 million. And the Kripkes were not alone. In July 1998 another Buffet-made-millionaire story emerged featuring Polytechnic University professor Donald Othmer and his wife, Mildred, who some decades ago invested most of their savings with Buffett, an old family friend. After the couple passed away — he in 1995 and she in April 1998 — it was learned that they left most of their money to their favorite charities. However, their level of giving was astounding, and clearly distinguished from the typical academic couple, leaving a combined estate of $750 million.

Warren Buffett on the cover of a July 1999 edition of "Business Week," part of the business press coverage of Buffett in the late 1990s.

In late November 1999, Buffett, now 69 years old, was named “investor of the century” in a survey by the Carson Group, placing him ahead of other well-known investors such as Peter Lynch and John Templeton. But not everyone agreed that Buffett was the most astute investor, especially as the high-tech craze overtook Wall Street.

“Warren’s Lost It”

In 1999, after Berkshire reported a very small net increase per share for its investors, several newspapers ran stories about the demise of Warren Buffett. As the high-tech stock run up continued into 2000, Warren Buffett was considered by some of the more “go-go” investors of that day as something of a “has been” — an investor who had peaked who was even called “extinct” for staying out of high tech stocks. He was seen as a “your-father’s-Oldsmobile” investor at a time when all the kids were buying up those hot, high-tech Lamborghini type stocks. Buffett was skeptical of high-tech stocks and how they made money. Buffett’s remarks, though politely received, were seen as out of touch with the “new paradigm” of high technology and ever-rising internet stock valuations. He warned of an overvalued market that was heading for trouble. In fact, at that famous summer gathering of media, technology and financial moguls at Sun Valley, Idaho, Warrren Buffett was asked to give the concluding talk in July 1999. His remarks, though politely received, supported the view among the smart set that Buffett was out of touch with the “new paradigm”of high technology and ever-rising internet stock valuations.

Buffett’s talk — complete with stock market history, slides and charts, careful Warren Buffett reasoning, and a share of corny examples — delivered a message that most of his high-tech listeners and their financial sidekicks were not keen to hear. There was no “new paradigm,” Buffett said. The market could only yield what the economy produced, and this market was way out of sync in that respect. The next seventeen years, he explained, might not look much better than the dismal 1964-to-1981 period when the Dow had gone exactly nowhere. “If I had to pick the most probable return over that period,” he said, “it would probably be six percent.” But many investors — including those listening to Buffett’s words — expected much higher returns, more in the neighborhood of thirteen to twenty-two percent. Buffett’s message that day was largely ignored — until March 2000, when the “dot com” bubble began to implode. Much of Buffett’s message that day was ignored and dismissed — until March 2000, when the “dot com”bubble began to implode. Yet for a time, Buffett was considered by the smart money as “out of it” and “losing his edge;” a guy who had missed the high-tech moment and was now rationalizing his mistake.

But Warren Buffett was still a businessman the nation would turn to in time of crisis. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Buffett appeared on the Sunday CBS television news magazine, 60 Minutes, as one of three then prominent business figures — along with former General Electric CEO Jack Welch, Jr. and Robert E. Rubin, former U.S. Secretary of Commerce — to help calm the public and assure the nation that the economy could weather the terrorists’ attack on New York’s financial center.

Social Issues

Warren Buffett has been guided throughout life by a certain set of business values that shaped his investment strategy — tough-minded capitalist tendencies for the most part, the kind that can often be insensitive to worker, community, and other social values. On occasion, Buffett made statements that cast him as uncaring capitalist, focused primarily on financial gain. But he also had experiences that moved him to address the side effects of his investments as well as the general excesses of market capitalism.

|

Buffett Politics Warren Buffett’s father, Howard, was a Republican, and a three-term member of U.S. Congress from 1943 to 1949. Like his father, Warren Buffett was a Republican, too — for a time. By the early 1960s, however, he switched parties. “I became a Democrat basically because I felt the Democrats were closer by a considerable margin to what I felt in the early 60s about civil rights,” explained Buffett in 1993 comments to a Forbes reporter. “I don’t vote the party line. But, I probably vote for more Democrats than Republicans.” He has, however, been bipartisan in his political campaign giving.  U.S. Senator Hillary Clinton and Warren Buffett. In 1987, he made donations to the presidential campaign of Senator Bob Dole, Republican of Kansas. He has also supported fellow Nebraskans in their political endeavors, including the 1992 presidential campaign of Democratic Senator Bob Kerrey, and the campaign of Rep. Tom Osborne, Republican and former football coach at the University of Nebraska. In 2000, he gave money to the presidential campaign of former Senator Bill Bradley, Democrat of New Jersey and supported the U.S. Senate campaign of Hillary Clinton, Democrat of New York. In 2003, Buffett donated to the presidential campaign of Senator Bob Graham, Democrat of Florida. He has also supported Senator Russell D. Feingold, Democrat of Wisconsin, and Representative Christopher Shays, Republican of Connecticut, leaders in the fight for campaign finance changes.  California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger & Warren Buffett. In August 2003, Buffett was named an adviser to Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger who became California’s governor that October in a special recall election to replace then-Governor Gray Davis. In the 2008 national election, Buffett endorsed Barack Obama for president, stating that he was at odds with Republican candidate Senator John McCain’s views on social justice issues. |

Early on, in the late 1950s, Buffett had an experience in which he received a dose of bad press as a result of some of his investments. The bad notice came in 1958, after he bought a small windmill-maker in Beatrice, Nebraska called Dempster Mill Manufacturing. In this deal, he proceeded to milk this company’s assets and put up the remains for sale. Local papers called it like it was: heartless, big-city financier does a number on local business. Buffett discovered then that he had little stomach for that kind of social critique; he did not like being attacked or painted the ogre. The incident proved a turning point, or at least one that made him more sensitive to repercussions of his money making. Buffett wanted to be a good guy, loved and admired, but he also wanted to become one of the world’s richest businessmen. How to do that was the real trick, and he didn’t always succeed.

In the mid-1960s, he established the Buffett Foundation, which began disbursing a small portion of money for various causes, mostly to family-planning clinics. In the late 1960s, he worked to integrate Omaha’s segregated country clubs, and in the 1970s, through Nebraska newspapers he owned, became involved in bringing the spotlight on Nebraska famous Boy’s Town and some questionable uses and expenditures of its endowment. The papers, in fact, won a Pulitzer for the stories.

In 1982, Berkshire instituted a corporate philanthropy program that allowed share- holders to direct a portion of the company’s charitable contributions. With this policy, Buffett said he hoped to foster an “owner mentality” among shareholders, who responded enthusiastically, with more than 95 percent participating each year since the program’s inception.

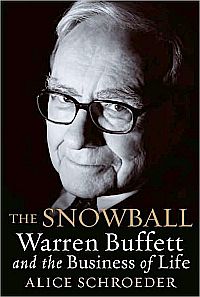

In 1986, when he could have made his business a private equity fund, and closed to public scrutiny for the purpose of avoiding certain tax consequences, Buffett chose instead to keep Berkshire Hathaway a public company, paying a tax cost of some $185 million. Some observe that this was part of Buffett’s wanting favorable public notice, and that he had “exchanged cash for an audience,” as Michael Lewis put it in a 2009 New Republic review of the Buffett biography, Snowball.

Still, at times Buffett would act as an old-fashioned capitalist– exploiting weakness, being insensitive to workers, driving hard bargains, or otherwise not worried about consequences. In 1987, for example, he said of investing in tobacco: “I’ll tell you why I like the cigarette business. It costs a penny to make. Sell it for a dollar. It’s addictive. And there’s fantastic brand loyalty.” Buffett would later soften his views on tobacco, noting at his annual shareholder meeting in 1994 that investments in tobacco were “fraught with questions that relate to societal attitudes….” and that he would “not like to have a significant percentage of my net worth invested in tobacco businesses.” He added that although the economy of the tobacco business may be fine, “that doesn’t mean it has a bright future.” Buffett would also use his annual letter to shareholders to speak out on issues of the day, or to criticize certain practices, as he did in March 1999 when he accused fellow CEOs of manipulating earnings figures with accounting tricks, praising efforts by then SEC chairman Arthur Levitt to end such practices.

In October 2002, Buffett announced he would give the Nuclear Threat Initiative $2.5 million over five years and become adviser to its board. The group, founded by Ted Turner and former Sen Sam Nunn, aims to reduce the threat of nuclear, biological and chemical weapons.

More Love, Less Money

In 2003, life changed for Warren Buffett. His wife and long time partner, Susie Buffett, was diagnosed with cancer at the age of 72 and would pass away a year later. Buffett began thinking differently then, and according to some observers, he became much more public. Alice Schroeder, writes in her book on Buffett, The Snowball:“…Before 2003 Buffett’s need for attention had been satisfied by a few interviews a year and the shareholder meeting. He had always been careful and strategic in his cooperation with the media (if not always forthcoming about just how cooperative he had been). But starting around the time of Susie’s illness, for whatever reason, he had begun to need the mirror of media attention, television cameras especially, almost like a drug. The intervals he could tolerate without publicity were growing shorter. He cooperated with documentaries, spent hours talking to Charlie Rose [moderator of the late night PBS Charlie Rose Show], and became such a regular on CNBC that it started to prompt puzzled queries from his friends.”

“Basically, when you get to my age,” Buffett would say to a group of business school students around 2003, “you’ll really measure your success in life by how many of the people you want to have love you actually do love you.” Buffett added that he knew people who had a lot of money, and who got testimonial dinners and hospital wings named after them. “But the truth is that nobody in the world loves them.” Warren Buffett wanted people to love him.

Warren Buffett on the cover of ‘Fortune” magazine, July 2006, one of many such stories in the wake of his June 2006 announcement to give away most of his wealth.

The Big Give

In June 2006, Buffett announced that he gradually would give away 85 percent of his Berkshire holdings to five foundations in annual gifts of stock, starting in July 2006. The largest contribution would go to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Buffett pledged to give the foundation approximately 10 million Berkshire Hathaway Class B shares spread over multiple years through annual contributions – a total 2006 value of approximately $30 billion. The Gates foundation is focused on world health, improving U.S. libraries, and high school education. Bill and Melinda Gates, in fact, credit Buffet with helping to inspire their thinking about giving money back to society. With the dramatic announcement of Buffett’s gift, there came a round of news stories and media appearances, some made jointly with Bill and Melinda Gates, and a number by Buffett alone.

In addition to his own philanthropy, Buffett has also occasionally prodded America’s wealthiest to do more. In October 2007, he issued a challenge to members of the Forbes 400 richest Americans list, saying he would donate $1 million to charity if the collective group (or a significant number of them) would admit they pay less taxes, as a percentage of income, than their secretaries. Days after issuing the challenge, Buffett appeared before Congress to encourage it to keep the estate tax. Armed with a few Forbes 400 issues at the ready, he told the hearing that “dynastic wealth, the enemy of a meritocracy, is on the rise.” He has also spoken out on the market system and wealth distribution: “The market system is not perfect in any kind of distribution of wealth, and taxation is a way you get to the excesses of what the market system produces and where you take care of the people that get the short straws. In a country as prosperous as we are, nobody should get a really short straw.”

Warren Buffett's investing suc- cess being touted by "U.S. News & World Report," 2007.

Other Issues

In 2007, Buffett and Berkshire demonstrated some sensitivity to environmental concerns when PacifiCorp, a subsidiary of his MidAmerican Energy Company, cancelled six proposed coal-fired power plants. The cancellations came in the wake of pressure from regulators and citizen groups, including a petition drive organized by Salt Lake City real estate broker Alexander Lofft and directed at Buffett personally. Some 1,600 petitioners — citizens, business owners, public servants, and others — appealed to Buffett in a letter explaining that further coal generation in Utah would compromise health, obscure viewsheds, contaminate watersheds, thin the snowpack, and compromise local economic gains and property values.

Protest over the Klamath River.

Money’s tendrils, it seems, can lead to some unpleasant places, even as Buffett tries to do the right thing.

|

“A-Rod & LeBron”  NY Yankee, Alex Rodriguez.  LeBron James and Warren Buffett on a July 2009 golf outing at Sun Valley, Idaho. |

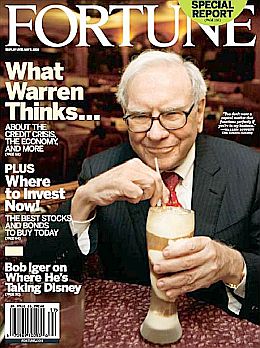

April 2008 Fortune features story on “What Warren Thinks...,” with cover quote: “You don’t want a capital market that functions perfectly if you’re in my business.”

“…The billionaire investor is out talking to cable TV anchors. To magazines. To share- holders. To Congress. To foreign investors. To a former Wall Street analyst who is writing a book about him.

He’s generating newsy sound bites at press conferences. On airplanes. In impromptu TV interviews outside his home. Even in faraway places such as China, South Korea and major cities in the euro zone, where he just got back from a “European Tour.”

He’s even popped up in a CNBC documentary, The Billionaire Next Door: All Access, which delves into all things Buffett. Not to mention a recent guest appearance on the daytime soap opera All My Children….

But then came the economic crisis of September 2008. In some ways, the crisis helped put Buffett on even more of a celebrity track — now using his reputation to help explain the crisis, provide some perspective, and again help to reassure the nation. Buffett’s “dance card” for interviews, counsel, and economic assistance filled up with ever more appointments. Not the least of these were CEO callers from Fortune 500 companies in some distress, such as General Electric, a one-time Buffett darling.

In the financial crisis of 2008 Warren Buffett’s “Wall Street cred” and business celebrity were called upon to help companies in distress, here in a pitch for G.E.

A Word for G.E.

During the 2008 economic meltdown on Wall Street, the venerable General Electric corporation became part of the carnage, and Warren Buffet’s “business celebrity,” as well as his deep pockets, were tapped to help ease G.E.’s pain. On September 30, 2008, in an early morning phone call with G.E. CEO Jeffery Immelt, Buffet agreed to help G.E. to the tune of $3 billion — in return for which Buffett received a new issue of preferred stock and warrants which would allow Berkshire to buy an equal amount of common stock over the next five years. As Fortune magazine writers Geoff Colvin and Katie Benner explained in an October 2008 article “GE Under Siege,” the special preferred shares issued to Buffett carried a 10 percent coupon, which is paid out by GE from after-tax profits, making it some of the most expensive capital GE could then acquire. But G.E.’s Jeffrey Immelt — who had gone to Omaha for meetings with Buffett and had consulted with him often, according to Fortune’s Colvin and Benner — “was willing to pay a steep price for the reassurance the famed investor’s endorsement would bring.” Buffett soon appeared in advertisements for the company, lending his name, image and a personal endorsement over his signature for GE and its future. In one ad, shown above, the copy that ran with Warren Buffett’s photo offered the following: “Warren Buffett says… ‘GE is the symbol of American business in the world… I am confident that GE will continue to be successful in the years to come’.” Buffett and Berkshire also invested $5 billion in Goldman Sachs a week earlier, with Buffett praising Goldman in a press release and TV interviews. He also appeared on a variety of business and talk shows during the economic crisis, including CNBC a number of times, The Charlie Rose Show, and others.

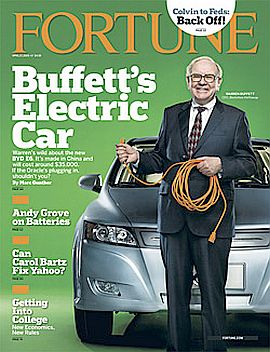

April 2009 Fortune magazine features Warren Buffett’s investment in electric car technology. Click for copy.

In November 2009, CNBC featured Buffett and Bill Gates in a two man cable TV special aired with an audience of business students at Warren’s alma mater, Columbia Business School in New York City. Buffett and Gates answered questions from students in an hour-long show hosted by Becky Quick on the state of the economy, America’s status as a financial superpower, the American Dream, corporate social responsibility and more.

Buffett and Berkshire would continue to surface in the business and mainstream press throughout 2009 and 2010 whenever a major deal was announced, as in Berkshire’s acquisition of the Burlington Northern / Sante Fe railroad, a huge acquisition and “bet on the future” as Buffett called it — at $44 billion in total stake, the largest acquisition in Berkshire Hathaway history. Berkshire and Buffett also made news in January 2010 when the company was added to the Standard & Poors’ flagship S&P 500 stock index.

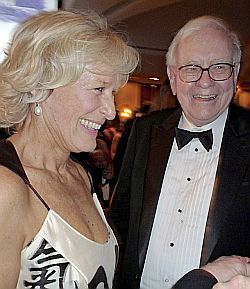

Warren Buffett with actress Glenn Close at the White House Correspondents Dinner in Wash., D.C., May 9, 2009. Photo, Reuters/Jim Bourg

Since this story was first written in early 2010, Warren Buffett and Bill Gates have launched “The Giving Pledge,” a campaign to encourage America’s wealthiest families to commit to giving away most of their money to philanthropic causes. The campaign targets billionaires and was made public by Buffett and Gates in June 2010. As of December 2010, more than 50 billionaires — including Paul Allen, Michael Bloomberg, George Lucas, T. Boone Pickens, Ted Turner, and Mark Zuckerberg — have signed on.

For additional stories at this website on business history and related topics, see for example: “Empire Newhouse, 1920s-2012” (the rise of Sam Newhouse and family as newspaper/magazine/publishing powers and “culture makers,” with magazines such as Vanity Fair and The New Yorker, among others); “Murdoch’s NY Deals, 1976-1977″ (Rupert Murdoch’s newspaper & magazine growth, including his takeover of Clay Felker’s New York Magazine); “Ted Turner & CNN, 1980s-1990s” (Ted Turner biz bio & rise of cable TV industry, mergers with Time-Warner and AOL, Jane Fonda, etc.); and, “Wall Street’s Gekko, 1980s-2010” (the 1987 Hollywood film, ethics lessons learned?, and subsequent use of Gekko character in business press). Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

_________________________________

Date Posted: 26 February 2010

Last Update: 4 May 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Celebrity Buffett, 1960s-2010,”

PopHistoryDig.com, February 26, 2010.

_________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

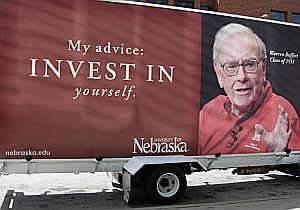

Warren Buffett, Class of 1951, makes an educational pitch for the University of Nebraska in a billboard ad. |

Warren Buffett on “The Charlie Rose Show.” |

2008 political cartoon featuring candidate Barrack Obama highlighting Warren Buffett’s views on taxes. |

Warren Buffett at 2007 annual meeting in Omaha flanked by son Peter and daughter Susie. Photo, Nati Harnik / AP. |

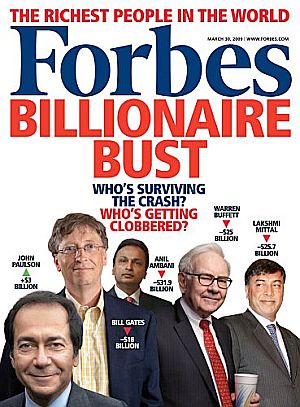

Forbes, March 2009, with Warren Buffett as one of the “clobbered” billionaires due to the 2008 economic downturn. |

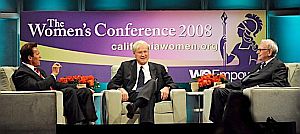

From left, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, MSNBC-TV host, Chris Matthews, and Warren Buffett at The Women's Conference in Long Beach, CA, Oct 22, 2008. |

You know you’ve made your mark on popular culture when they start quoting you on T-shirts. |

Screen shot from a 2008 CNBC television story featuring Warren Buffett, one of many such appearances there. |

Warren E. Buffett, left, with Chicago Cubs baseball great and Hall-of-Famer, Ernie Banks, at minor league game in Omaha, August 10, 2007. Photo, Matt Miller/Omaha World-Herald. |

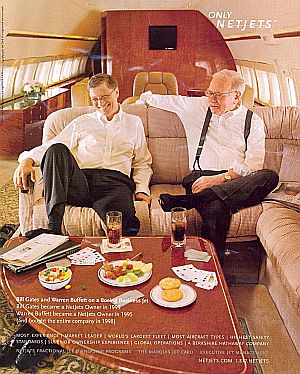

A Net Jets, Inc, magazine ad featuring Bill Gates and Warren Buffett riding in a Boeing buisness jet provided by the Net Jets company. Warren Buffett bought the company in 1995 and Bill Gates is also a stockholder in Net Jets. |

Warren Buffett greeting Jeffrey Immelt, CEO, General Electric, before panel discussion at Georgetown University, March 13, 2007 in Wash., DC, hosted by U.S. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson. Photo, Chip Somodevilla. |

“Buffett Explains Investment Goals,” New York Times, Friday, March 4, 1966, Business & Finance, p. 49.

“Buffett Is Said to Take Stake of 10-15% in Geico,” New York Times, Friday, August 13, 1976, Business & Finance, p. 71.

“The Press: Krusty Kay Tightens Her Grip,” Time, Monday, February 7, 1977.

Katharine Graham, Personal History, New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1997.

Carol Felsentha, Power, Privilege, and The Post: The Katharine Graham Story, Seven Stories Press: New York, 1993.

“Buffett’s Firm Buys Buffalo Evening News,”Washington Post, February 18, 1977, p. D-9.

Robert Metz, “Market Place; Annual Report With Candor,” New York Times, Tuesday, April 15, 1980, Business & Finance, p. D-8.

Warren Buffett, “When Cable TV Comes to Town,” Washington Post, Sunday Outlook Section, September 7, 1980, p. D-7. (1,363 words)

Bryan Burrough and John Helyar, Barbarians at the Gate, 1987.

Robert J. Cole, “Coke Says Buffett Has 6.3% Stake,” New York Times, Thursday, March 16, 1989.

Bart Ziegler, AP, “The World’s Wealthiest — Japanese Developer 1st; Bill Gates 38th,” Seattle Times, Monday, July 9, 1990.

Michael Abramowitz, “Venerating Finance’s High Priest; Eager Investors Flock To Hear Warren Buffett,” Washington Post, April 30, 1991, p. D-1.

“Annual Reports: The Best of Buffett,” Time, Monday, April 15, 1991.

Andrew Kilpatrick, Warren Buffett, The Good Guy of Wall Street, Andy Kilpatrick Publishing, Birmingham, Alabama, September 1992 (hardcover) and January 1995 (paperback), 304pp.

Robert Lenzner, “Warren Buffett’s Idea of Heaven: ‘I Don’t Have to Work With People I Don’t Like’,” Forbes, October 18, 1993, pp. 40-45.

Andrew Kilpatrick, Of Permanent Value: The Story of Warren Buffett, (2 Vol.), Andy Kilpatrick Publishing, Birmingham, Alabama, 1994 (revised almost yearly since; 2009 “Woodstock edition” is 1,972 pp.).

Floyd Norris, “Literary Factors May Be Driving Berkshire Hathaway’s Surge,” New York Times, Friday, February 10, 1995.

Francis Flaherty, “For Mr. Buffett’s Stocks, The Business Is the Key,” New York Times, Saturday, February 18, 1995.

John Rothchild, “How Smart Is Warren Buffett?,”Time, Monday, April 3, 1995.

David Einstein, Jeff Pelline, “Disney’s Stunning Deal to Buy ABC; Biggest Media Firm in World Would Emerge,” San Francisco Chronicle, Tuesday, August 1, 1995, p. A-1.

James F. Peltz, “Company Town: Disney’s Mega-Merger; The ABCs of a Deal – a Big Winner For ‘Oracle of Omaha’ Buffett, a $2.1-Billion Vision of Profit,” Los Angeles Times, August 1, 1995

Roger Lowenstein, Buffett: The Making of An American Capitalist, Orion Publishing Co.,1995, reprinted in 1997 and 2008, 512pp.

Michael A. Hiltzik and Claudia Eller, “Chemistry Made Talks Quick, Quiet,” Los Angles Times, August 1, 1995.

Associated Press, “Buffett to Take Shares in Merged Disney-Capital Cities,” New York Times, March 8, 1996.

Warren E. Buffett, Chairman of the Board, “Chairman’s Letter” (for the year 1996), Berkshire Hathaway Inc., February 28, 1997.

N. R. Kleinfield, “Enriched by His Friendship With an Agnostic, a Rabbi Finances a Storied Legacy,” New York Times, May 9, 1997.

Douglas Harbrecht, “Warren Buffett’s ‘Woodstock Weekend’ Love-In,” Business Week, May 4, 1998.

Karen W. Arenson, “Staggering Bequests by Unassuming Couple,” New York Times, July 13, 1998.

Michael Eisner with Tony Schwartz, Work in Progress, New York: Random House, 1998, Chapter 14, “Landing ABC.”

Robert P. Miles, 101 Reasons to Own the World’s Greatest Investment: Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1998, revised edition 2001, 240pp.

Richard A. Oppel, Jr., “Buffett Deplores Trend of Manipulated Earnings,” New York Times, March 15, 1999.

“Warren Buffett: Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man…,” Fool.com, August 25, 1999.

Larry Kanter, “Brilliant Careers: Warren Buffett,” Salon.com, August 31, 1999.

Dunstan Pria, “100 Years and Many Millions; Buffett Named Investor of The Century,” Washington Post, November 25, 1999, p. E -1.

“Buffetts Give $134 Million to Charities,” New York Times, December 28, 1999

Jay Steele, Warren Buffett: Master of the Market, New York: Avon Books, 1999, 224 pp.

Janet Lowe, Damn Right!: Behind the Scenes with Berkshire Hathaway Billionaire Charlie Munger, John Wiley & Sons, 2000.

“After the Attacks; On the Economy,” New York Times, September 15, 2001.

Judith Miller, “Warren Buffett Moves to Help Group Trying to Reduce Nuclear and Biological Threats,” New York Times, October 4, 2002.

“Greenspan, Unlike Buffett, Sees Derivatives as Positive Influence,” New York Times, March 8, 2003.

Daniel Kadlec and Julie Rawe, “Comeback Crusader,” Time, Monday, March 10, 2003.

James O’Loughlin, The Real Warren Buffett: Managing Capital, Leading People, (paperback), April 2004.

David Henry, “Learn To Think Like Warren Buffett,” Business Week, February 14, 2005.

Carol J. Loomis, “Warren Buffett Gives Away His Fortune,” Fortune, June 25, 2006.

“An Hour With Warren Buffett, Bill Gates & Melinda Gates,” The Charlie Rose Show, June 26, 2006.

Elizabeth Olson, “Suits; Buffettball,” New York Times, April 1, 2007.

“A Conversation With Warren Buffett,” The Charlie Rose Show, May 10, 2007.

Alex Crippen, “History Lesson: Warren Buffett’s ‘Crazy’ Coca-Cola Bargain Buy,” CNBC.com, Thursday, July 19, 2007,

Murray Chass, “On Baseball — Buffett Is Invested in Rodriguez,” New York Times, August 10, 2007.

Brad Hamilton and James Fanelli, “Warren Buffett Pushed A-Rod to Yankees,” New York Post, November 17, 2007.

Kate Kelly and Dana Cimilluca, “Alex Rodriguez Gets a Surprise Assist from Fan in Omaha;

“As Yankee Slugger Whiffed on Contract, He Turned to Buffett and Goldman,” Wall Street Journal.com, November 17, 2007.

Danielle Sessa, “Buffett Told Rodriguez to Call Yankees on Contract, Person Says,” Bloomberg.com, November 18, 2007.

Matthew Miller, “Gates No Longer World’s Richest Man,” Forbes, March 5, 2008.

Adam Shell, “Warren Buffett Hones Rock-Star Status,” USA Today, June 4, 2008.

“A Conversation With Warren Buffett,” The Charlie Rose Show, October 1, 2008, during which Buffett discusses topics including: the cause of the economic crisis, the government’s rescue plan, ways to boost the economy, the investment climate, and other issues.

Walter Hamilton, “Buffett Girds GE With $3-Billion Investment,” Los Angeles Times, October 2, 2008.

Geoffrey Colvin and Katie Benner, “GE Under Siege,” Fortune, October 27, 2008, pp. 84-94.

Alex Crippen, “Warren Buffett’s Celebrity-Style Endorsements of GE & Goldman Aren’t Helping the Stocks …Yet,” CNBC.com, October 7, 2008.

Alice Schroeder, The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life, New York: Bantam, September 2008, 976pp.

Michael Lewis, “The Master of Money,” (Book Review of The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life, by Alice Schroeder), The New Republic, Wednesday, June 3, 2009.

Peter Dreier, “Human Rights Activists Protest NBA-Linked Sweatshops,” Huff- ingtonPost.com, June 14, 2009.

“Warren E. Buffett,” Times Topics, NewYorkTimes.com, July 2009.

Warren Buffett Timeline, 1957-1974, About.com.

“Warren Buffett Biography,” Biogra- phy.com, A&E Television Networks, 2009.

Michael Corkery, “Deal Journal: Warren Buffett Takes Bankers to the Woodshed,” Wall Street Journal, November 13, 2009,

Associated Press, “Oregon’s Klamath Basin Deal Helps Farmers and Fish,” New York Times, February 18, 2010.

“The Giving Pledge,” Wikipedia.org.

“The Giving Pledge,” Official Website.

___________________________