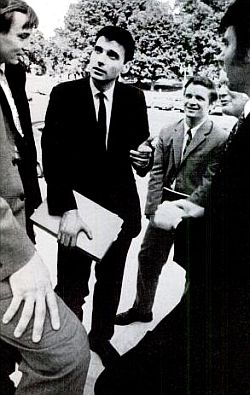

Ralph Nader and his “Raiders” – law, medical and engineering students – on the steps of U.S. Capitol in late summer 1969.

Loosed on official Washington in the 1960s and 1970s and dubbed “Nader’s Raiders” by Washington Post journalist William Greider, these teams of Ralph Nader acolytes churned out all manner of books, reports and investigative probes aimed at improving the law, making government work better, and/or holding corporate powers to account.

A small cottage industry of publisher-worthy paperbacks resulted, some becoming bestsellers, and all with messages that stirred the public policy pot.

In the process, official Washington was challenged and changed, investigative journalism was re-ignited, and public interest advocacy became part of the culture.

What follows in this piece is a look back at some of that history, how the Nader teams and Nader reports came about, and what effect they had.

In the late 1960s, Ralph Nader was fresh from his own success with a best-selling book, Unsafe at Any Speed, which took the automobile industry and Congress to task about auto safety. In that fight, Nader also became embroiled in a battle with General Motors after the company hired private detectives to follow him and investigate his past, trying to discredit him as a Congressional witness and consumer spokesman. That incident, covered in a separate story, backfired on GM, with the company’s CEO apologizing to Nader during highly publicized U.S. Senate hearings. With his new national credential as a rising consumer advocate, Nader sought to expand the range of his activities beyond auto safety. By summer 1968, Nader began assembling teams of law school students to undertake investigative studies of government agen-cies. He had a bigger vision of what might be possible and a long list of issues that needed attention – from food safety and environmental pollution, to anti-trust enforcement and energy policy. What he needed was more Ralph Naders – though he never put it in exactly those terms. In fact, the idea may have risen by way of students themselves who wrote to Nader after his auto safety notoriety. In January 1968, for example, Andrew Egendorf, a graduate of MIT who had entered Harvard Business School, wrote to Nader with a friend offering to work for him that summer if Nader would consider working with students. Whether this was the genesis of the plan, or was already something Nader was considering, is unclear. In any case, by the summer of 1968, Nader began assembling teams of law school students to undertake investigative studies of government agencies that dealt with consumer, environmental, food safety, and other issues. He would start with one agency and one team. Seven law school students were recruited to focus on the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the federal agency charged with protecting consumers from shoddy products, fraudulent business practices, and deceptive advertising. The students Nader gathered to focus on the FTC were: Edward F. Cox, Yale Law School; Robert C. Fellmeth, Harvard; John E. Schulz, Yale; Judy Areen, Yale; Peter A. Bradford, Yale; Andrew Egendorf, MIT/Harvard; and William Taft IV, Harvard.

Paperback book cover for a later edition of the first “Nader’s Raiders” report on the Federal Trade Commission, Grove Press, 1970, 241pp.

But even before the official release, the Nader team had begun making waves with some of what they were finding. They had one dust-up early on with FTC officials in the summer when they were conducting interviews and gathering data at the agency. In that incident, Nader team leader, John Schulz, had words with FTC chairman Paul Rand Dixon after some persistent questioning and was thrown out of Dixon’s office. Shulz had asked for a copy of a monthly FTC memo detailing complaints made to the agency. Dixon told him that the document was for FTC use only. Dixon also decreed by letter there would be no more Nader team interviews that summer, unless cleared with him.

However, Dixon’s letter made its way to Time magazine, where a story appeared on the incident in September 1968 titled, “Nader’s Neophytes.” Time also divulged some of what the Nader team was finding, indicating their study would show the FTC as a toothless watchdog, reluctant to go after big advertising offenders, and sometimes withholding reports from the public.

Edward Cox, a member of the Nader FTC team, helped generate a Wall Street Journal story in the summer of 1968 on some political dirt he discovered in his research – a purely patronage office in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, which was manned by a friend of FTC Chairman Dixon. As Cox would later tell this tale, recalling his stint with Nader that summer:

…A memorable event for a Washington newcomer was the impact of a Wall Street Journal article.“…I began to see how our hard work and Nader’s guidance and contacts might have an impact after all.” – Edward T. Cox My research had identified a patronage office in Oak Ridge, Tennessee manned by a friend of Chairman Dixon’s, Judge Castro C. Geer, Jr. Judge Geer’s patron in Congress was Joe Evins, a Tennessee representative and chairman of the House subcommittee which approved the FTC’s budget. Nader told me to take the information to Jerry Landauer, one of the premier muckraking reporters in the Journal’s DC office. I will never forget the scene: Landauer, cigarette in his mouth, calling various sources to confirm the information, pounding out the story on his typewriter, and muttering genuinely sympathetic noises about poor Judge Geer who was about to get skewered by his story. This was the first major story generated by our [Nader study team] work, and I began to see how our hard work and Nader’s guidance and contacts might have an impact after all.

As the “Nader Raider” study teams were assembling, Ralph Nader was receiving national press as a consumer advocate, as in this November 1968 ‘Newsweek’ story.

A 1970 edition of the Nader Raiders FTC book showed the three authors during testimony on Capitol Hill. Click for book.

In Congress, during the spring and summer of 1969, Sen. Abraham Ribicoff (D-CT), then chairman of the Government Reorganization Subcommittee of the Senate Government Operations Committee, was holding hearings on bills to establish an Office of Consumer Affairs. FTC issues were also covered at those hearings, with the Nader group offering testimony on their study. At one point during the hearings, Ribicoff praised the Nader FTC authors for their work, while leveling digs at the establishment press and the government: “Bureaucracy being what it is, I am fascinated by your ability to get in so deep, and get so much information. I am sure that you gentlemen are the envy of the large number of reporters here.”

FTC Chairman Paul Rand Dixon, however, described the Nader report for the Wall Street Journal as “a hysterical anti-business diatribe and a scurrilous, untruthful attack on the [FTC’s] career personnel and an arrogant demand for my resignation.” The report had indeed called for Dixon’s resignation and a complete overhaul of the agency. And by April 1969, the FTC had come to the attention of the new Nixon Administration. President Nixon urged the American Bar Association to undertake an independent investigation of the FTC, which they completed that September. The ABA’s report painted conclusions even more dismal than the Nader team had presented. Paul Rand Dixon resigned. When, under the new leadership of Casper W. Weinberger, reforms began taking place within the FTC, the New York Times announced the fact in a front-page headline on June 9, 1970: “FTC Maps Change to Aid Consumer; Major Reorganization Set by Chairman– Agency Was Nader Target.”

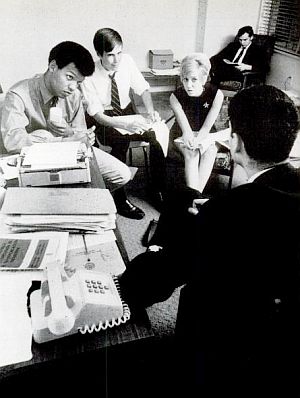

Ralph Nader meeting with several of his “raiders,” late 1960s.

While the FTC study was underway, plans were made to staff up several more Nader study teams to probe other agencies. On February 10, 1969, a small ad was placed in the Harvard Crimson student newspaper at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts under the title, “Nader’s Raiders.” The text of the ad read: “Graduate students in medicine, biology, life sciences, engineering, and law are needed this summer to work with Ralph Nader in an investigation of various government programs. Call Robert Fellmeth, 868-1593.” An avalanche of responses resulted. By that summer, more than 100 students had been recruited from thousands of applicants. In short order, several more study areas were set, generally focusing on food, agriculture, air and water pollution, and interstate commerce. By this time, Nader had also founded his Center for the Study of Responsive Law based in Washington, which would serve as the operating base for the study teams and research.

Ralph Nader, back to the camera, meeting with “raiders” in 1969 – from left, Julian Houston, James Fallows, Marian Penn, and Robert Fellmeth, Photo, Life magazine.

“…Most lawyers are too hung up on clients. The most important thing a lawyer can do is become an advocate of powerless citizens. I am in favor of lawyers without clients. Lawyers should represent systems of justice. I want to create a new dimension to the legal profession. What we have now is democracy without citizens. No one is on the public’s side. All the lawyers are on the corporation’s side. And the bureaucrats… don’t think the government belongs to the people.

“For example, the industries, corporations and lobbyists manipulate the federal commissions and agencies. The Interstate Commerce Commission has always been a tool of the railroads, the bus lines and the trucking industry. The Department of the Interior has been easily influenced by the oil and gas industries. The Department of Agriculture has been an instrument of the tobacco industry. No one represents the public interest. Lawyers are never where the needs are greatest. I hope a new generation of lawyers will begin to change that.”

During the 1969-72 period, more than a dozen “Nader Raider” reports were launched, most of which became paperback books. Among the earliest of these were the five Nader reports that followed the FTC study: The Chemical Feast, Vanishing Air, The Interstate Commerce Omission,Water Wasteland, and Sowing the Wind. A brief look at each of these studies, as well as a few others, follows below.

The Chemical Feast

Work on the background reports that became a landmark “Nader’s Raiders” book on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration began in the summer of 1968. James S. Turner, a law student at Ohio State University, would become the project director and principal author. But more than a dozen Nader-recruited researchers worked on the project over two summers, eventually distilling their findings into a 273-page book, The Chemical Feast, published as a paperback by Grossman Publishers in 1970.

As the title suggests, there was more to the nation’s food system than met the eye, and, in fact, an onslaught of chemical food additives and pesticides was part of the equation, which Nader’s team uncovered in chapters with titles such as: “Cyclamates,” “Hidden Ingredients,” and “Food-Borne Disease.”

The book exposed the FDA’s lax oversight of the food industry, its corruption, and its connections with big food and drug companies. FDA appeared more concerned with protecting industry profits at the expense of public health.

“What they turned up was truly shocking,” reported Choice magazine – “evasion of law enforcement, abdication of responsibilities, bureaucratic confusion, incompetence, favoritism, and even fraud… It should prove of interest to concerned citizens of all ages.”

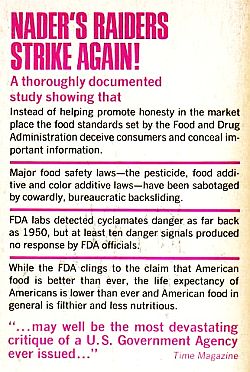

Back cover of “The Chemical Feast,” 1970.

The major food safety laws – including the pesticide, food safety and color additive laws – were sabotaged by the FDA, according to the study. “While the FDA clings to the claim that American food is better than ever,” explained The Chemical Feast’s back book cover, “the life expectancy of Americans is lower than ever and American food in general is filthier and less nutritious.”

A New York Times article in early April 1970 by reporter David E. Rosenbaum, used the following headline to describe the study: “F.D.A. Called Tool of Food Industry; Nader Unit Likens Its Rules to ‘Catalogue of Favors’.” Rosenbaum further wrote that the Nader FDA study revealed an agency “controlled by political pressures and unable and unwilling to protect the consumer.” The standards and regulations of the agency, Rosenbaum said of the report’s findings, “read like a catalog of favors to special interest groups.”

Time magazine said The Chemical Feast “may well be the most devastating critique of a U.S. government agency ever issued.” The report was first published in book form by Grossman in 1970, then reprinted three times in 1971, 1972 and 1974. In 1976, Penguin Books also published it in paperback form.

ICC Blasted

Another in the first batch of Nader reports was The Interstate Commerce Omission, a scathing review of the failings of the Interstate Commerce Commission, then an 83-year-old federal agency charged with regulating interstate commerce by rail, trucking, shipping and pipelines. The Nader study group undertaking this report was headed up by Robert Fellmeth, and his team delved deeply into the ICC’s record, sending out mail surveys, conducting more than 500 interviews, and doing detailed statistical analyses. In March 1970, they issued a 1,200-page draft report, which Time magazine called “devastating in detail.”

The essence of their report was that the ICC really didn’t regulate the 17,000 or so transport entities under its charge so much as operate a cartel on their behalf. The commission, they found, was in effect presiding over thousands of local transport monopolies, protecting inefficient carriers from competition at the expense of the public. They also found a cozy relationship between the ICC and the industries they regulate, with industry trade groups also paying for meetings, food and hotel accommodations on junkets to “surface transportation meccas” such as Hawaii, Puerto Rico and the Bahamas.

The Interstate Commerce Omission argued that the public good would best be served if the ICC were abolished altogether – and along with it, the Civil Aeronautics Board and the Federal Maritime Commission. All three of those entities could be replaced by a single agency, the Nader team charged, an agency that would then be able to set a coherent national transportation policy, relying less on regulation and more on markets to set rates. Doing so, they argued, would sharpen competition among companies in all forms of transport.

Vanishing Air

The release of the Nader study-group report on air pollution – titled Vanishing Air – was a well-timed report, coming exactly as the public and Congress were beginning to focus on environmental issues. On April 22,1970, the first Earth Day – the brainchild of Senator Gaylord Nelson (D-WI) to organize students and other citizens with teach-ins and demonstrations on behalf of action to clean up the environment – was a huge success, with more than 20 million people becoming involved in events and demonstrations across the nation. Meanwhile, the U.S. Congress and the Administration of Richard Nixon were then maneuvering with proposals for needed changes to an old and outdated Clean Air Act, as urban pollution episodes – fueled largely by automobile-generated smog – had raised national concerns about public health.The Nader study-group report on air pollution came right in the middle of the growing national outcry over environmental pollution. The work of the study group had begun in 1969 led by John C. Esposito, who held degrees from Long Island and Rutgers universities as well as a law degree from Harvard. He was assisted by Larry Silverman, associate director of the project, who was a graduate of St Johns College and held a law degree from the University of Pennsylvania. This Nader task force included at least ten other members, including graduate students in medicine and engineering. They set about documenting air-pollution health hazards around the nation, using case studies of various cities while also focusing on the role of Congress and the outdated National Air Pollution Control Administration (NAPCA), which operated under the very weak 1967 Clean Air Act.

Automobile pollution became a major concern in the late 1960s, and a topic for political cartoonists, illustrated by this sample from the “Washington Star” newspaper.

Other polluters targeted in the Nader study included big manufacturing and the energy industry. Congress and the political process were also hit hard, including a presumed champion of clean air, Senator Edmund Muskie (D-ME), whose subcommittee on pollution and federal environmental laws, the report charged, “resulted in a ‘business-as-usual’ license to pollute for countless companies across the country.” The report also charged that Senator Muskie had issued “politically expedient platitudes” rather than “real leadership.”

Borrowing a page from Rachel Carson and her landmark 1962 book Silent Spring, which used an opening fictional story on pesticide health threats to introduce the urgency of her message, the Nader Study Group on Air Pollution also used this devise in Vanishing Air, including a fictional account of an atmospheric inversion in a major city that trapped pollutants endangering public health. In fact, as the paperback version of Vanishing Air came out in July 1970, a mass of stagnant air lodged itself over the eastern seaboard of the U.S., putting a meteorological lid on the entire region for several days and trapping all manner of industrial and automotive pollutants. The episode got public attention, while provoking a few editorials (see sidebar below) and several U.S. Senate speeches.

|

“The Great Dirty Cloud” In July 1970, as an atmospheric inversion trapped pollutants all along the East Coast, the incident became the main topic of discussion throughout the nation and the media –including the possibility of banning cars from urban centers. In one editorial, The New York Times wrote: “Through the polluted haze that for days has hung over the East Coast cities from New York to Atlanta, nothing is clear but a timely warning. Urban areas are getting perilously close to the point where they have to choose between the internal combustion engine and breathable air…” “…[W]hat has up to now been regarded as personally hysterical and economically unthinkable may yet become a reality. Until the gasoline engine can be made pollution-free or a clean substitute for it developed — eventualities at least ten years in the future — the automobile may actually have to be banned from the centers of major American cities… In the present New York crisis a prohibition on all non-essential traffic may yet have to be invoked in certain areas… “  A 1970s’ episode of smog enveloping New York’s Manhattan. Photo from EPA Documerica gallery /National Archives. |

Vanishing Air and the Nader Study Group on Air Pollution, meanwhile, continued to have an impact that year, helping to create the pressure for enactment of the 1970 Clean Air Act. That law, in fact, was the toughest anti-pollution measure ever approved by Congress up to that point and was signed grudgingly by Richard Nixon in December 1970, as Senator Ed Muskie in the end had proved a clean air champion and leader in the fight, setting tough 1975 goals for the automakers.

Water Wasteland

During the late 1960s and early 1970s water pollution, like air pollution, was a growing problem across the nation. In northeast Ohio, the Cuyahoga River was so polluted with oil and petrochemicals that is caught fire, and nearby Lake Erie was biologically dead. Added to these were any number of other lakes and rivers across the nation that were severely polluted, among the worst rivers, for example were: the Buffalo, the Escambia, the Passaic, the Merrimack, the Rouge, the Ohio and the Houston Ship Canal. Ralph Nader had formed a student Study Group in 1969 to investigate these and other water pollution problems across the country.

David Zwick was a young Harvard law school student when Ralph Nader recruited him to begin work on water pollution. After nearly two years of study, with a team of 26 student researchers and Radcliffe co-author/editor Marcy Benstock, Zwick released the study group’s 700-page report in April 1971. The study was later published in paperback book form by Grossman Publishers under the title, Water Wasteland.

What the Nader team found was a federal water pollution control program that was “a miserable failure.” After 15 years of programs and $3.5 billion in spending dating to 1956, the level of pollution they found – except in isolated instances – had not been significantly reduced. In fact, it had grown worse. Industrial pollution , they found, was by far the major problem, eclipsing domestic sewage sources by 4-to-5 times the volume. More problematic were the 500 some new chemicals that industry was releasing into waterways, many of which were not being removed by water treatment systems.

Water pollution was a major problem in the 1970s.

Ralph Nader meeting with some study team members in Washington, 1969.

In October 1972, a revised Clean Water Act passed in Congress with a bipartisan majority overriding a veto by President Nixon. The new law included a “citizen suit” provision allowing citizens to initiate legal action to enforce the law when the government failed to do so. That provision — an important new tool for environmental enforcement — was soon incorporated into other environmental laws. It had been pushed by David Zwick, who also created a new organization — Clean Water Action — to implement the new law. Zwick’s co-author on Water Wasteland, Marcy Benstock, went on to her own activist glories, stopping the Westway highway project in New York City and heading up the Clean Air Campaign.

Sowing The Wind

Billed as the Nader report on “food safety and the chemical harvest,” Sowing the Wind was the name of the study that investigated the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). It focused mostly on meat and poultry inspection, but also pesticide use and other agriculture-related topics.This Nader study team began their work in 1969 under the direction of Harrison Wellford, one of the original raiders and also the first executive director of Nader’s Center for Study of Responsive Law.

Sowing the Wind found that USDA was failing to protect Americans from bad meat and dangerous chemicals. It charged that the 1967 Wholesale Meat Act – once thought to be a reform measure – had succumbed to business as usual within USDA.

The report found there was no regular monitoring for bacteriological contamination in federal meat inspections even though there were at least 30 diseases then believed to be transmitted through meat and poultry. USDA also continued to permit the use of herbicides such as 2,4,5-T, despite evidence indicating dangers to human and animal life.

Also reported in Sowing The Wind were lab and field data that raised concerns about possible birth-defects and cancers linked to the synthetic hormone DES, used to fatten cattle. USDA’s ties to big agribusiness in the meat, poultry, and pesticide industries were probed as well.

Ralph Nader, left, pushed back from table, meeting with students who produced, "Old Age: The Last Segregation"(see cover below).

Meanwhile, the first round of “Nader Raider” reports – and the first four or five books to result from these studies – had sold in the neighborhood of 450,000 copies or more. And there were many more reports and books to come. In fact, there were at least 17 raider reports published as books by 1972. And the money from the sales of these and forthcoming books would be plowed back into Nader’s organizations. On the back covers of many of Grossman Publishers’ editions, for example, was the note: “All royalties from the sale of this book will be given to the Center for Study of Responsive Law, the organization established by Ralph Nader to conduct research into abuses of the public interest by business and government.”

More Raider Reports

|

|

|

|

By early November 1971, plans had been announced for a very ambitious “Nader Raiders” project: an investigation of the U.S. Congress — its members, its committees, and its effectiveness. In this vast undertaking, Nader would enlist the aid of some 1,000 researchers across the country. But as work on the Congress study began, other Raider reports kept coming (click on any book cover for Amazon page on that book).

In November 1971, a study of the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation came out – Damning The West – which concluded the Bureau of Reclamation had “outlived its usefulness” and should halt its “senseless damming of the West.” Later that month another Nader team, headed by James Phelan and Robert Pozen, both Yale law school students, issued The Company State – a report on the giant chemical company, E.I. du Pont de Nemours Co., commonly known as DuPont. That study charged that DuPont essentially ran the state of Delaware for its own narrow corporate interests over those of the general public. Jerry Cohen of the Washington Post called it “a classic work on the impact of corporate power.” Publishers Weekly said it was “well written, well organized,” and “bristling with data” — a study that portrayed “dynastic family power in a velvet glove.” Also in 1971 came The Water Lords, a Nader report by James M. Fallows and his team focusing largely on the environmental impacts of the pulp and paper industry in Savannah, Georgia. And there were others in 1971, among them: Old Age: The Last Segregation, by Claire Townsend, on the indignities and frauds practiced by nursing homes; and, The Workers, by Kenneth Lasson, which profiled nine workers in an attempt to bring the circumstances of worker lives more clearly to the general public. Among researchers on this project, for example, was Peter Lance, who spent one month each living with the families of a brick layer, a garbage collector and a policeman in Boston as part of the workers profiled in that study. For many of the Nader studies, the initial raw reports, usually longer and more detailed, were first released to the press, followed by a final, more polished paperback book for the general public, which may account for some variation in publication dates.

|

|

|

|

In September 1972, a Ralph Nader Study Group at the Center for Auto Safety released the book, Small – On Safety: The Designed-in Dangers of The Volkswagen, by Lowell Dodge. Previously in 1965, when Nader did his landmark book, Unsafe at Any Speed, which skewered the Corvair, he was criticized for not looking at the Volkswagen in the same way. With Small–On Safety, he and the Center for Auto Safety did just that – and they found the VW bug and the microbus to have a range of problems. Among some of the issues they documented from court records and files at the Center of Auto Safety were the Beetle’s erratic handling, its rollover potential, and its “up-in-flames” riskiness following an accident, this due to a poorly-designed fuel system and defective gas cap. Volkswagen mounted a public relations campaign to deflect the book’s criticisms.

Another Nader report first released in 1972, was The Politics of Land, which investigated the land use game in California, highlighting in part, the role of developers and land speculators in the state. This study was headed up by Robert Fellmeth, who had already worked on two other Nader reports. A paperback version would be published a year later. Also in 1972, came The Madness Establishment, a Nader Study Group report on the National Institute of Mental Health. It was authored by Franklin D. Chu and Sharland Trotter and it found, among other things, that the Community Mental Health Centers Act had resulted in a mismanaged and ineffective bureaucracy. The Madness Establishment was issued in book form by Grossman Publishers in 1974.

By September 1972 Nader had released his study of Congress as a Bantam paperback book titled, Who Runs Congress: The President, Big Business, or You? Distilled from the work of hundreds of researchers and thousands of pages of material, a team of three Nader analysts –Mark J. Green, James Fallows, and David Zwick – wrote the final product. At the book’s release, Nader charged that Congress was giving away its powers to committee chairmen, the executive bureaucracy, and special interests. The book was well-received by critics and the American public, and Who Runs Congress? shot to No. 2 on the New York Times bestseller list in October 1972, and hit No. 1 for the month of November. The book eventually went through four different editions and print runs of more than one million copies. The book remains one of the best-selling volumes written on Congress. When it first appeared, it was widely read by the incoming class of newly-elected Congressional legislators in 1974 following the Watergate crisis, including the 47 freshmen Democrats that year dubbed the “Watergate Babies.” Who Runs Congress? also helped change the climate of public opinion toward Congress and Congress’ own perception of itself.

Other Studies

The Nader Study Group report on antitrust enforcement, “The Closed Enterprise System,” with Mark Green & others, 1972. Click for book.

The Monopoly Makers examined the cartel behavior of numerous industries, their collusion with federal agencies meant to regulate them, and the costly consequences for the public. Other volumes followed, including: The Closed Enterprise System, a report on antitrust enforcement by Green, Beverly C. Moore, Jr., and Bruce Wasserstein in 1972; Corporate Power in America in 1973, a collection of essays examining business abuses, edited by Nader and Green; and in 1976, Taming the Giant Corporation: How the Largest Corporations Control Our Lives, with coauthor Joel Seligman.

There were also Nader documents and reports released on how to organize and build public interest organizations at the state and local level, such as Action for A Change: A Student’s Manual for Public Interest Organizing, by Ralph Nader and Don Ross.

The Raider Legacy

By 1972, there were 17 “Nader’s Raiders” reports published as books, with many more to come in subsequent years.

|

“The Powell Memo” One measure of the effectiveness of Ralph Nader and his Raiders came in the summer of 1971. A corporate lawyer named Lewis F. Powell, Jr., would write something of a famous memo in which Nader’s work was cited as harmful. Powell at the time was with a law firm in Richmond, Virgnia, and would also represent tobacco interests on occasion at the state legislature. He was also a member of the boards of directors of 11 corporations, including tobacco giant Phillip Morris. In August 1971, Powell wrote a long memo to his friend Eugene Sydnor, Jr., Director of the Education Committee for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. The memo’s title was, “Attack on The American Free Enterprise System.” It was dated August 23, 1971, two months prior to Powell’s nomination by President Richard Nixon to become a U.S. Supreme Court judge. The “Powell Memo,” as it later came to be known, was confidential and not available to the public at the time it was written, and did not surface until after his confirmation to the Court.  Lewis F. Powell, Jr., in a U.S. Supreme Court portrait. Nader was not alone among those Powell singled out for special attention in the “assault on the enterprise system.” But it was clear he did not hold in high regard the work that Nader and his associates had undertaken. So Powell set about, with his memo, to offer a detailed plan of public education, politics, and other activities to counter what he believed the activists were out to damage. The Powell Memo would come to be regarded as something of a blueprint for business and allied organizations to do battle with the perceived politics of the left. It is credited with influencing a round of corporate activism and conservative think tank capacity-building that occurred in subsequent years designed to shift public attitudes, leading to the creation of organizations such as the Heritage Foundation, the Manhattan Institute, the Cato Institute, Citizens for a Sound Economy, Accuracy in Academe, and other similar organizations. Since Powell’s memo, business and conservative organizations have in fact, “out-Nadered Nader,” copying many of his techniques, but building even more powerful legal, fundraising, political action, and research organizations to further their agendas. And Powell himself, in his Supreme Court tenure and opinions, helped advance “corporate free speech” and corporate financial influence in elections, the latter of which many believe has put America on a perilous course. |

2010: Joan Claybrook & Clarence Ditlow (Center for Auto Safety) on Capitol Hill. |

James Fallows became a speechwriter for Jimmy Carter and a top journalist. |

Joe Tom Easley, former Nader Raider. became a professor of law. |

Robert Fellmeth, former Nader Raider, at the University of San Diego. |

Harvey Rosenfeld, former Nader activist, founded Consumer Watchdog. |

Andrew Egendorf, former Nader Raider, co-founded tech company, Symbolics.com. |

As for the Raiders, many of them moved on to government service; to careers in politics and journalism; or to heading up activist, environmental, or community organizations. For example, by 1977, after the election of Jimmy Carter, a number of the Nader activists rose to positions within the Administration. Joan Claybrook, who ran Nader’s Public Citizen, became head of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. James Fallows, now a nationally-known journalist, became head speechwriter for Carter. And Harrison Wellford, after leaving Nader in 1973 and serving as chief of staff for Senator Phil Hart, became Carter’s associate director of the Office of Management and Budget.

But years later, after Nader’s Raiders had gone on to other work and into their own professions, several offered their recollections and perspective on those earlier years in Washington. “We bought Ralph’s idea,” explained former Raider, Joe Tom Easley, describing the motivation behind the Raiders’ work during an interview for the documentary film, An Unreasonable Man. Easley by then had taught at several law schools, including the University of Virginia, the University of Georgia, and American University.

“…We were going to make the country what it ought to be,” continued Easley, “– by working and pressing the system to work. Ralph had decided to do about six or eight teams attacking different agencies… And the quality of the reports that came out was on the whole pretty high. There was never one of the Nader reports of that summer or any summer since then that was exposed as a fraud.”

Robert Fellmeth, one of the original Nader’s Raiders in 1968 who went on to become executive director of the Center for Public Interest Law at the University of San Diego and the Children’s Advocacy Institute, observed of his earlier days as a Raider:

…When you’re young, you don’t realize you’re doing something you have no business doing. How are you qualified? There are professors who should be there who have studied the agency for 20 years. What are you doing? It doesn’t even occur to you. And in fact, we did write a good critique [the FTC report] that stands the test of time. And the year after we wrote it, President Nixon asked the ABA [American Bar Association] to look at the agency. Sure enough, they came up with the same critique that we did, and it lead to some changes in the statute.

Fellmeth and other Raiders praise Nader for his vision and his “letting-us-run-with-it” style – with the Raiders doing the work and “Ralph orchestrating it from a distance,” as Fellmeth put it. “He was the kind of person who said, ‘You’re in charge of this. Here’s the mission. Do it.’ And then he’d review the final product and give you a sign off at the end.”

Harvey Rosenfield, who worked as a Raider in the late 1970s and early 1980s with Congress Watch, and later headed up a consumer watchdog group in California, explained in a similar context:

“I think that the people [Nader] attracted came principally because they wanted the opportunity to work for justice in the country, and he created an environment where you could do that. If you did it well, there was no limit to how much you could achieve. He never stood in the way of anybody. He never demanded the credit if somebody else was doing the work. He was happy to have them get as much credit as they could from the public or the news media.”

Andrew Egendorf, one of the original Raiders from 1968, went on to co-found a technology company named Symbolics.com. He offered this view of Nader and business:

…Everyone gives Nader, I think, an unfair reading. Everyone says he’s anti-business, and he wants to tear down the capitalistic system. He’s not like that at all. His view was simply that the interest of the producers ought to be to support the interest of the consumers, because the whole system is based on consumption. So why don’t we have a system that has constraints on it that require the producers interest to be aligned with the consumers interests?

The problem was that the producers were all monopolies or oligopolies, and the consumers were just all individuals with no clout at all. All he wanted to do was level the playing field, give consumers the same kind of clout as an oligopoly.

One Man’s Vision

Ralph Nader, circa 1975.

Ten years later, there were at least a half dozen new Nader or Nader-related organizations at work with dozens of staff, publications pouring from each of them, and measurable public policy change on at least a dozen or more fronts. That, of course, was just the beginning, as there would be three more decades of Nader-styled advocacy to follow.

Today, nearly fifty years later, the investigative spirit and techniques that Ralph Nader and his “Raider” teams brought into the public square are still at work in numerous organizations in Washington and elsewhere, with researchers and policy analysts digging into the public record, tracking government regulations, and watchdogging corporations.

See also at this website, “GM & Ralph Nader, 1965-1971.” For other story choices on “Politics & Culture,” “Print & Publishing,” or “Environmental History,” please visit those respective pages, or go to the Home Page for additional choices. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing and continued publication of this website. Thank you. — Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 31 March 2013

Last Update: 2 April 2020

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Nader’s Raiders, 1968-1974,”

PopHistoryDig.com, March 31, 2013.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“History of the Center for Study of Responsive Law,” CSRL.org, Washington, D.C.

David Bollier, Citizen Action and Other Big Ideas: A History of Ralph Nader and the Modern Consumer Movement, Chapter 3, “The Office of Citizen,” The Nader Page, Nader.org.

“Youth: Nader’s Neophytes,” Time, Friday, Septem- ber 13, 1968.

William Greider, “Law Students, FTC Tangle Over Apathy,” Washington Post, November 13, 1968, p. A-3.

John D. Morris, “FTC Incompetent, Says Inquiry Set Up by Nader,” New York Times, Monday January 6, 1969.

Morton Mintz, “Student Group Blasts FTC, Demands Dixon Quit,” Washington Post, Times Herald, January 6, 1969, p. A-2.

Morton Mintz (Washington Post), “Nader’s Raiders Vex FTC Chief; Scathing Report for Consumers,” The Geneva Times (New York),Wednesday, January 15, 1969, p. 8.

“Investigations: A Youthful Blast,” Time, Friday, January 17, 1969.

Ruth Glushien, “Tricks of the Trade,” Brass Tacks, The Harvard Crimson, February 6, 1969.

“Nader’s ‘Raiders’ Scheduling Pollution Probe This Summer,” Washington Post, Times Herald, March 22, 1969, p. E-5.

John D. Morris, “Nader Recruits 80 New Student ‘Raiders’ to Investigate the Operations of a Dozen Federal Agencies,” New York Times, Sunday, June 1, 1969.

“Nader’s Raiders,” The Washington Post, Times Herald, June 8, 1969, p. 38.

Ursula Vils, “Consumer Crusade by Nader’s Raiders,” Los Angeles Times, July 13, 1969, p. G-3.

Morton Mintz, “Nader’s Raiders Blast Truck Safety Practices,” Washington Post, Times Herald, September 3, 1969, p. A-3.

Ray Zeman, “County Seeking Nader’s Help in Car Smog Fight,” Los Angeles Times, September 19, 1969, p. B-1.

Jack Newfield, “Nader’s Raiders: The Lone Ranger Gets a Posse,” Life, October 3, 1969, pp. 55-63.

Simon Lazarus, Review, ” ‘The Nader Report’ On the Federal Trade Commission,” New York Times, Sunday, October 19, 1969.

Nat Freedland, “Nader Report on FTC,” Los Angeles Times, November 2, 1969, p. C-54.

John D. Morris, “Nader’s Raiders Sue for C.A.B. Data,” New York Times, Wednesday, November 26, 1969.

“‘Nader’s Raiders’ Study Includes Rail Report,” Washington Post, Times Herald, March 15, 1970.

Christopher Lydon,”Abolition of I.C.C. Urged in Report by Nader Unit; Law Students Say ‘Political Hacks’ Should Yield …,” New York Times, Tuesday, March 17, 1970,

“Savannah River Study Set; Team of Students, Working Under R Nader’s Direction, To Study Savannah River Pollution…,” New York Times, Monday, March 23, 1970.

“Consumerism: Nader’s Raiders Strike Again,” Time, Monday, March 30, 1970.

Arthur John Keefe, “Is The Federal Trade Commission Here To Stay?,” American Bar Association Journal, February 1970, p. 188.

Barry Goldwater, “Nader’s Raiders Ignore the NLRB,” Los Angeles Times, April 5, 1970, p. E-7.

David E. Rosenbaum, “F.D.A. Called Tool of Food Industry; Nader Unit Likens Its Rules to ‘Catalogue of Favors’,” New York Times, Thursday, April 9, 1970, p. 17.

“Agencies: Up Against the Wall, FDA!,” Time, Monday, April 20, 1970, p. 18.

E.W. Kenworthy, “Muskie Criticized by Nader Group; His Role in Pollution Fight Is Questioned in a Report,” New York Times, Wednesday, May 13, 1970.

Maggie Savoy, “Nader Hits ‘Violence’ of Big Business,” Los Angeles Times, May 27, 1970, p. E-1.

“FTC Maps Change to Aid Consumer; Major Reorganization Set by Chairman– Agency Was Nader Target” New York Times, June 9, 1970.

“Nader to Examine Pulp Industry,” Washington Post, Times Herald, June 10, 1970, p. A-12.

“Nader’s Raiders Ready to Study U.S. Banks,” Los Angeles Times, June 16, 1970, p. E-12.

John D. Morris, “Nader Plans Expanded Summer Investigations of Government and Business,” New York Times, Sunday June 21, 1970.

Review of, “Vanishing Air: The Ralph Nader Study Group Report on Air Pollution, By John C. Esposito,” Kirkus Reviews, July 1970.

Philip Hager, “Nader Group Inspects State Land Policies,” Los Angeles Times, July 12, 1970, p. D-6.

Robert Kirsch, “Nader’s Raiders Volumes Keep Heat on Bureaucrats,” Los Angeles Times, July 21, 1970, p. E-6.

John Leonard, Books of The Times “Nader’s Raiders Ride Again” (Review of Vanishing Air. The Ralph Nader Study Group Report on Air Pollution: by John C Esposito and Larry J Silverman), New York Times, Friday, July 24, 1970.

Robert Dietsch, “How Crusader Ralph Nader ‘Raids’ For Consumer,” Congressional Record, August 3, 1970, p. E7284.

Robert J. Samuelson, “CAB Hires a Nader Raider,” Washington Post, Times Herald, October 22, 1970, p. F-12.

Peter Braestrup, “Nader Group Probing Civil Service Agency,” Washington Post, Times Herald, October 30, 1970, p. A-2.

Stuart Auerbach, “Nader Group Faults Standards for Medical Treatment,” Washington Post, Times Herald, November 9, 1970, p. A-2.

Morton Mintz, “Nader Asks Students to Give to Public Interest Projects,” Washington Post, November 16, 1970, p. A-3.

Philip D. Carter, “Nader Charges Ga. Paper Plant Is Outlaw Polluter of Savannah,” Washington Post, Times Herald, January 22, 1971, p. A-2.

Nan Robertson, “Nader-Raiding No Plush Job,”New York Times, Friday, January 29, 1971.

Barnard Law Collier, “The Story of a Teen-Age Nader Raider; Nader Raider,” New York Times, Sunday, March 14, 1971.

UPI, “Ralph Nader Attacks Industrial Polluters,” The Times-News (Hendersonville, NC), Monday, April 12, 1971, p. 8.

“Nader Hits Anti-Pollution Effort,” St. Petersburg Times (Florida), April 12, 1971.

“Study Belittles Pollution Effort,” The Tuscaloosa News (Alabama), April 12, 1971.

Associated Press, “Ohio River Pollution On Increase; Nader Task Force Says Mills Here Add to Problem,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 13, 1971, p. 2.

UPI, “Environmental Chief Backs Nader on Water Pollution,”New York Times, April 14, 1971.

“Environment: Nader on Water,” Time, Monday, April 26, 1971.

Donna Scheibe, “Patti Agrees With Nader on Convalescent Homes,” Los Angeles Times, July 4, 1971, p. SF/A-4.

“Business: How It Feels to Be Naderized,” Time, Monday, July 5, 1971.

“Nader ‘Raider’ Probe of Auto Assn. Planned,” Los Angeles Times, July 6, 1971, p. 9.

UPI, “Nader Group Plans Study Of Comsat’s Operations,” New York Times, Monday, July 12, 1971.

Peter Braestrup, “Nader Task Force Accuses USDA of Allowing Bad Meat,”Washington Post, Times Herald, July 18, 1971, p. A-2.

Walter Rugaber, “Nader Group Calls U.S. Lax on Meat Inspection and Pesticides,” New York Times, Sunday, July 18, 1971.

UPI, “Nader Hits Meat Quality,” The Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah), Monday, July 19, 1971, p. 4-A.

“Nader Hits US Meat Inspection,” Boston Globe, July 18, 1971.

“Nader Claims…Government Regulators Bowed To Agribusiness,” Times Daily, July 18, 1971.

David C. Wallace, Associated Press, “Nader Hits Farming Regulators,” Daily News (Bowling Green, Kentucky), Sunday, July 18, 1971, p. 5.

“Cattleman Calls Nader’s Meat Report ‘Inept and Outdated’,” Los Angeles Times, July 22, 1971, p. H-20.

William F. Buckley, Jr., “Tables Turned on Nader: ‘He Puts Out…a Shoddy Product’,” Los Angeles Times, August 4, 1971, p. B-7.

Mike Causey, “Nader’s Raiders Make Waves in CSC,” Washington Post, Times Herald, August 5, 1971, p. G-5.

Leonard Ross, Review, “The Chemical Feast; The Food and Drug Administration, by James S. Turner, 273pp., New York: Grossman Publishers,” New York Times, Sunday, August 8, 1971.

William L. Clairborne, “Tedious Study is Key Tool of Nader’s Raiders,” Washington Post, Times Herald, August 16, 1971, p. A-3.

“Planner Lauds Nader Report on Land Use,” Los Angeles Times, September 3, 1971, p. A-21.

“Auto Assn. President Calls Nader ‘Dictator’,” Los Angeles Times, September 21, 1971, p. A-12.

Eliot Marshall, “St. Nader and His Evangelists,” The New Republic, October 23, 1971, p.13.

“Nader Plans Investigation Of Congress,” Washington Post, Times Herald, November 3, 1971, p. A-3.

Paul Houston, “Ralph Nader: The Man and His Crusaders,” Los Angeles Times, November 3, 1971, p. A-1.

John D. Morris, “Congress Facing Inquiry by Nader; 1,000 People Expected to Take Part in Study,” New York Times, Wednesday, November 3, 1971.

United Press International (UPI), “Nader Group Scores Reclamation Unit,” New York Times, Sunday, November 7, 1971.

Walter Rugaber, “Nader Study Says du Pont Runs Delaware,”New York Times, Tuesday, November 30, 1971,

“Delaware Is Du Pont ‘Company State’: Nader,” Los Angeles Times, November 30, 1971, p. A-7.

Kenneth Lasson, The Workers: Portraits of Nine American Jobholders. Prepared for Ralph Nader’s Center for Study of Responsive Law. Afterword by Ralph Nader. New York: Grossman Publishers 1971.

John Rothchild, “Finding the Facts Bureaucrats Hide,” The Washington Monthly, January 1972.

Arthur Allen Leff, Book Review, “The Closed Enterprise System; Ralph Nader’s Study Group Report on Antitrust Enforcement. By Mark J. Green,” New York Times, Sunday, April 30, 1972.

Robert H. Harris, and Daniel F. Luecke, “Pollluters and Regulators,” Review of Water Wasteland, Ralph Nader’s Study Group Report on Water Pollution, Science, May 12, 1972, pp. 645-647.

Angus Macbeth, “Book Review: Water Wasteland,” Fordham Urban Law Journal, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1972, Article 8.

UPI, “Nader Report Scores U.S. Unit On Mental Health Center Plan,” New York Times, Sunday, July 23, 1972.

Book Review, “Small – On Safety: The Designed-in Dangers Of The Volkswagen,” Kirkus Reviews, September 1, 1972.

“Nader Says Probe Shows Congress Is Abdicating Power,” Los Angeles Times, October 3, 1972, p.2.

Mary Russell, “President, Big Business Control Congress, Nader Says in Book,” Los Angeles Times, October 4, 1972, p. A-1.

Mary Russell, “Nader’s Profiles of 485 Members of Congress Unveiled,” Washington Post, Times Herald, October 22, 1972, p. A-20.

Book Reviews of Harrison Wellford, Sowing The Wind, in American Journal of Agricultural Economics, August 1973, pp. 541-542.

Michael W. Kuhn, Book Review [Water Wasteland], Santa Clara Lawyer, January 1,1973, pp. 356-359.

Simon Lazarus and Leonard Ross, “Rating Nader” (Reviewing two Nader books: The Monopoly Makers edited by Mark J. Green Sowing the Wind by Harrison Wellford ), New York Times, June 28, 1973.

David J. Weber, Book Review, Politics of Land, Ralph Nader’s Study Group Report on Land Use in California, in The Journal of San Diego History / San Diego Historical Society Quarterly, Fall 1974, Volume 20, Number 4.

Robert G. Vaughn, “The Freedom of Information Act and Vaughn V. Rosen: Some Personal Comments,”The American University Law Review, Vol 23, 1974, pp. 865-879.

Martin Gittelman, Book Review of The Madness Establishment, at “Community Mental Health: Problems and Prospects,” International Journal of Mental Health, Vol. 3, No. 2/3, (Summer-Fall 1974), pp. 195-200.

Associated Press, “Nader’s Raiders Have Moved Up To Capitol Hill,” Lakeland Ledger (Lakeland FL), April 17, 1977, p. 16.

“Nader’s Raiders,” An Unreasonable Man, Documentary Film on Ralph Nader, Independennt Lens/PBS.org.

Federal Trade Commission, 90th Anniversary Symposium, Speakers Panel, “The First 90 Years: Promise and Performance,” Moderator: Ernest Gellhorn; Speakers: William E. Kovacic, Marc Winerman, and Edward F. Cox, Federal Trade Commission Conference Center, Washington, D.C., September 22, 2004.

Edward F. Cox, “Reinvigorating the FTC: The Nader Report and the Rise of Consumer Advocacy,” Antitrust Law Journal, Vol. 72, No. 3, 2005, pp. 899-910.

“Robert Fellmeth,” Wikipedia.org.

“Andrew Egendorf,” Cheltenham High School Hall of Fame.

“The Powell Memo,” ReclaimDemocracy.org.

David Bollier, Citizen Action and Other Big Ideas: A History of Ralph Nader and the Modern Consumer Movement, Chapter 5, “Citizen Action: Chapter 5,” The Nader Page, Nader.org.

Karen Heller, “Ralph Nader Builds His Dream Museum – of Tort Law,” WashingtonPost.com, October 4, 2015.

_________________________________________