|

|

|

|

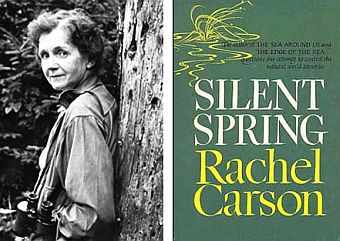

In three successive issues of The New Yorker magazine in June of 1962, a series of articles under the title “Silent Spring” began appearing. The covers of those New Yorker editions — June 16th, 23rd and 30th, and one story page — are shown at right. The articles were written by “reporter at large” Rachel Carson, a scientist and published author. Carson by then had worked at the U.S. Department of the Interior and had written earlier best-selling nonfiction books on the biology of the sea and coastal environments – including the award-winning The Sea Around Us of 1951. But the articles she offered in the New Yorker that June of 1962 were more hard-hitting than anything she had previously written. This time, Rachel Carson was sounding an alarm and delivering a critique.

Her articles offered disturbing accounts of how synthetic chemical pesticides – then used widely in agriculture and sprayed elsewhere for insect control – had become, in her words, “elixirs of death,” contaminating the environment, killing wildlife, and threatening human health. Carson’s articles were excerpted from a forthcoming book, also called Silent Spring; a book that would have a profound impact on society, environmental science, and public understanding of the natural world. Within one month of The New Yorker series, Carson and her book were making news and creating an uproar in the chemical industry. On July 22nd, 1962 a front-page New York Times story on the book used the headlines: “Silent Spring is Now a Noisy Summer; Pesticide Industry Up in Arms Over New Book; Rachel Carson Stirs Conflict – Producers Cry ‘Foul’.” The book itself, however, had yet to be released, with a publication date set for late September 1962.

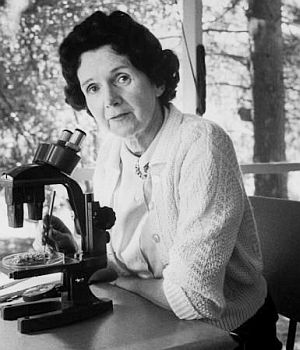

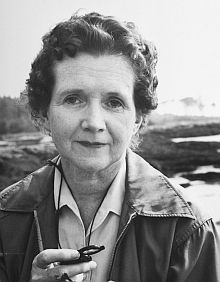

Rachel Carson shown here in a 1950s photograph alongside the cover of her landmark 1962 book, “Silent Spring,” Houghton Mifflin hardback.

What follows here – in this 50th anniversary year of Silent Spring’s publication – is a partial recounting of the book’s history, including pressures brought to bear on author and publisher, how society received Silent Spring, and how it helped change thinking and advance public understanding of ecology. First, some background on Rachel Carson – an unlikely and reluctant crusader – and how she came to the pesticide issue.

Rachel Carson

1929: College graduate Rachel Carson aboard boat at Woods Hole Biological Laboratory, Massachusetts.

Early 1930s: Rachel Carson photo from Johns Hopkins University.

That fall, she began graduate study at Johns Hopkins University, where she would also teach for a time, returning to Woods Hole in subsequent summers. By 1931 she worked in zoology at the University of Maryland, remaining there for five years. She completed her Master’s degree at Johns Hopkins in 1932 then did some post-graduate work at the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole.

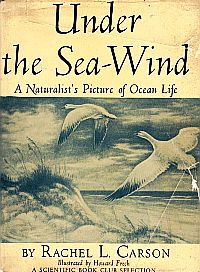

1941: First edition of Rachel Carson’s “Under The Sea Wind,” published by Simon & Schuster. Click for book.

By 1936 at the age of 29, she had become a junior aquatic biologist at the Fisheries Bureau, only the second woman to be hired by the Bureau for a full-time, professional position.

Writing became a part of what Carson did in her job at the Fisheries Bureau and also for outside publications. In September 1937 she published an article entitled, “Undersea,” in The Atlantic Monthly magazine. This led to her first book in 1941, Under the Sea-Wind, described by Carson as a series of descriptive narratives building in sequence on the life of the shore, the open ocean, and the sea bottom. The book featured the sanderling, a common sea bird, facing the rhythms of nature and an arduous migration. The book was published by Simon and Schuster. However, arriving in bookstores the day after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, it received little notice. Back at the Fisheries Bureau, meanwhile, she rose to chief editor of publications in 1949.

Rachel Carson, 1944, U.S. Bureau of Fisheries.

She then contacted the Fisheries Bureau director in Washington and in 1949 was granted permission for a ten-day cruise in the rough waters of the George’s Bank off coastal Maine. That cruise helped Carson in writing what would become her second book, The Sea Around Us. Meanwhile, in 1950, Carson had something of a personal scare as a confirmed breast tumor was found and removed, with no further treatment then called for.

Carson continued to work on her new book about the sea. However, getting to the final product wasn’t easy. A proposed article from the book’s research was rejected by numerous magazines, including the Saturday Evening Post and National Geographic.

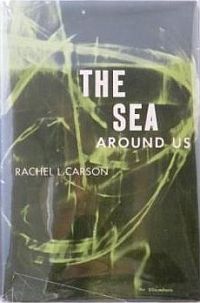

1951: Rachel’s Carson’s “The Sea Around Us” became her first bestseller, winning several book awards. Click for book.

“If there is poetry in my book about the sea,” she wrote upon receiving the National Book Award, “it is not because I deliberately put it there, but because no one could write truthfully about the sea and leave out the poetry.” A film version of The Sea Around Us was also produced as a documentary in 1953, which won the Oscar award that year for Best Documentary. Carson, however, was not happy with the result and would never sell film rights to her work again.

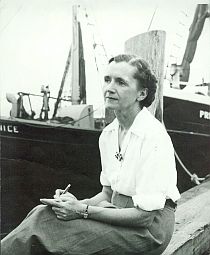

1951: Rachel Carson, Woods Hole dock at Sam Cahoon's Fish Market, just after publication of “The Sea Around Us.” Photo E. Gray, Lear Collection.

|

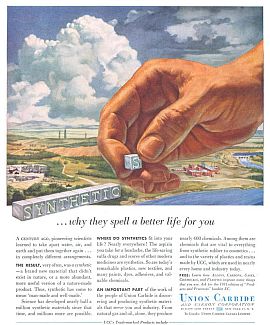

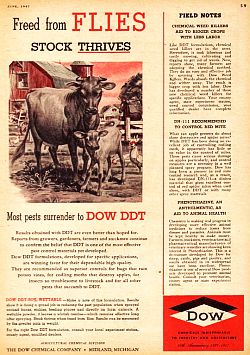

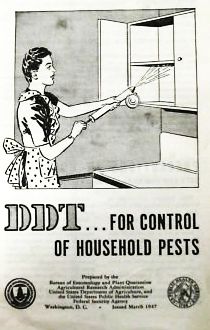

“Go-Go Chemistry”  1955: "Synthetics...why they spell a better life for you." - Union Carbide. The 1955 magazine ad at right – one of a number of Union Carbide’s “giant hand” ads from that era – touts the benefits of “synthetics” in building the good life. In July 1950, during a Dow Chemical Company open house for the media, the Detroit Free Press gave a gushing review of Dow’s “hidden house of wonders,” describing an amazingly inventive company turning out all manner of products for America’s every need: “The clothes you are wearing, the ice cream you had for lunch, your wife’s permanent wave, the pharmaceuticals in your medicine chest, your children’s toys and your automobile all most likely have ingredients in them which came from Dow.” Indeed, by 1958, Dow was the fourth largest chemical company in the U.S., turning out an array of several hundred chemical and plastic products.  June 1947 Dow Chemical ad for “Dow DDT.”  Cover of a March 1947 brochure on DDT from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. …There was little room in the 1950s for the advocates of the slow, thoughtful approach in any portion of life—business, science, or politics. The country was so firmly in control of itself and had tied technology so tightly to patriotism that to be skeptical, to be Robert Oppenheimer working to “retard” the hydrogen bomb program or an “alarmist” scientist warning of potential dangers of radioactive fallout, was to be a traitor. Nationwide publicity linking cigarettes to heart disease for the first time in 1954 was countered by advertisements that pointed out reassuringly that “More Doctors Smoke Camels Than Any Other Cigarette.” “The deadliest sin was to be controversial,” observed William Manchester in describing a generation that wanted “the good, sensible life” and that was “proud to be conservative, prosperous, conformist and vigilant defenders of the American way of life.” The largest group of college undergraduates were business majors, and industry leaders were lionized (General Motors president Harlow Curtice was Time’s Man of the Year in 1956). A free market, left to its own devices, was thought to be the most efficient path to productivity. In 1957 the Soviets simultaneously launched Sputnik 1 and the space race by taunting Americans with the specter of Russian superiority. Obeisance to technocracy took on patriotic as well as religious overtones. It was generally in the context of this world view that Rachel Carson stepped forward with her research on pesticides and what effect these chemicals were having on the natural world. |

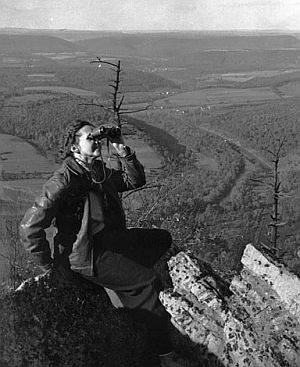

1945: Rachel Carson looking for raptors at Hawk Mountain, Berks County, Pennsylvania.

Rachel Carson did not set out to write a book about pesticides or do battle with the chemical industry. Rather, events of that era had drawn her into the fight, both professionally as a scientist and personally as a lover of the natural world. In her marine studies with the Bureau of Fisheries, she had begun to gather data on the effects of DDT and other pesticides on marine life. Since abnormalities often show up first in fish and wildlife, biologists were among the first to see the ill effects of chemicals in the environment.

Carson had also learned about various predator and pest control programs that were freely spreading pesticides in the environment with little regard for consequences beyond the target pest. In one of her earliest forays on the chemical issue, Carson had proposed an article to Reader’s Digest on evidence about DDT’s environmental damage, but the magazine turned her down. Carson at the time was still focused primarily on the ocean and costal environments, and writing her books on those topics.

National wildlife artist Bob Hines and Rachel Carson search out marine specimens in the Florida Keys around 1955. The two spent time in the field for the USFWS visiting Atlantic coast refuges gathering material for agency publications. Hines’ drawings also appear in “The Edge of the Sea.”

With that, Carson then huddled with Paul Brooks, her editor at Houghton Mifflin and then, William Shawn at The New Yorker. She agreed to start work on what might be a magazine piece and possibly something suitable for a chapter in a book on the same subject. That was all she had in mind at the time. She then set out to complete the work by the summer of 1958.

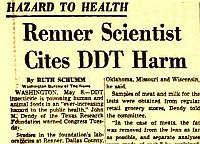

1951: DDT headlines in the “Dallas Morning News” reporting on a Texas scientist testifying in Congress.

Aerial pesticide spraying over livestock, 1950s. |

DDT spraying, beach area, in the 1950s. |

In 1957, landowners on Long Island, New York – including Robert Cushman Murphy, a retired ornithologist at the American Museum of Natural History, and Archibald Roosevelt, a son of former President Teddy Roosevelt – had brought a lawsuit to stop the spraying of DDT to kill gypsy moths in their area. Their lawsuit had some success, but the case went all the way to the Supreme Court which refused to hear it, although Justice William O. Douglas dissented in that decision, feeling the alarms that had been raised by experts warranted the court’s taking the case.

Rachel Carson had followed the proceedings of this case and was the beneficiary of a windfall of documents and scientific contacts that resulted. She was also following the Department of Agriculture’s “fire ant eradication program” which began in 1957 and used two potent insecticides, dieldrin and heptachlor, in a spraying campaign that wildlife experts would later call a fiasco.

Carson had also written a letter to the editor, published in the spring of 1959 in The Washington Post, that attributed a recent decline in bird populations—she called it the “silencing of birds”—to pesticide overuse. In late 1959, a great national furor also arose after cranberries were found to contain high levels of the herbicide aminotriazole, as the sale of all cranberry products was halted. Carson attended the ensuing FDA hearings and came away dismayed by the testimony and tactics of the chemical industry – which contradicted the scientific data she was finding.

“The more I learned about the use of pesticides, the more appalled I became,” Carson later wrote. “I realized that here was the material for a book. What I discovered was that everything which meant most to me as a naturalist was being threatened, and that nothing I could do would be more important.” Carson corresponded and met with other scientists who were documenting the environmental effects of pesticides in their own fields. Her connections with government scientists sometimes yielded confidential information. She also went into the federal agencies and national research libraries to do her digging, such as the Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health, and letter writing to other scientists as well.

July 1961: Rachel Carson seaside, examining specimen in jar. Life photo, A. Eisenstaedt.

Carson was a careful writer and would later explain that writing was hard work for her, sometimes working in longhand with difficult material before it was typewritten. By March 1960 a good portion of her book was finished in rough form, but that’s when she had a medical set back. An earlier breast tumor had actually been malignant, leading to a mastectomy in April 1960. Carson, in fact, was plagued by recurring personal illnesses, including arthritis, an ulcer, staphylococcus infections, and a continuing battle with cancer. Still, even as she battled these medical problems, with setbacks in her writing, she persevered through early 1962, working toward completion of the book. After consultation with her editor and agent, she settled on a title for the book – which earlier had been “The Control of Nature,” later changed to “Man Against the Earth,” and then changed again to something else. Paul Brooks, her editor at Houghton Mifflin, suggested using “Silent Spring, ” which he had proposed initially for the book’s chapter on birds. But “Silent Spring” suited the overall theme Carson was trying to get at, with chemicals not only “silencing spring” but also throwing the “balance of nature” out of kilter.

In early June 1962, the first of Carson’s articles appeared in The New Yorker magazine.

Initial Reaction

July 1962: New York Times front-page story and headlines on Rachel Carson’s then-forthcoming book, “Silent Spring.”

P. Rothberg, president of the Montrose Chemical Corporation of California, an affiliate of the Stauffer Chemical Company and then the nation’s largest producer of DDT, was quoted in the New York Times saying that Carson wrote not “as a scientist but rather as a fanatic defender of the cult of the balance of nature.” Carson’s New Yorker series had caught the attention of Chemical Week, one of the industry’s trade magazines, as soon as those pieces appeared. On July 14th, 1962, that magazine ran an editorial noting that Carson’s articles could not be dismissed as a “the work of a crank,” but that her technique was “more reminiscent of a lawyer preparing a brief…than of a scientist conducting an investigation.” Some chemical companies had assigned staff to reading the New Yorker articles line-by-line to find possible flaws. But one company, Velsicol Chemical Corporation, went straight to the ramparts.

Velsicol Chemical sent a letter to “Silent Spring’s” publisher.

Meanwhile, other reaction to the Silent Spring stories in The New Yorker had been positive. In Washington, Congressman John Lindsay (later to become mayor of New York and a presidential candidate), wrote to Carson telling her he found The New Yorker pieces to be “a persuasive contribution to public awareness of the dangers of our present pest control policy.” Lindsay inserted a portion of the one of the New Yorker articles into the Congressional Record.

President John F. Kennedy, shown here at an earlier January 15, 1962 press conference, did acknowledge Carson’s book at a later press conference, August 29, 1962.

Also in late August 1962, the CBS television network announced that it was planning to run a show on the book the following year for its “CBS Reports” documentary news show. Newspaper and magazine stories had also appeared reacting to The New Yorker series. In Business Week magazine, a September 8th story used the title, “Are We Poisoning Ourselves?” In Atlantic City, New Jersey, at a September 12th gathering of chemical industry officials and government scientists, Dr. C. Glen King, head of the Nutrition Foundation, charged that “one-sided” books like Silent Spring was whipping up public sentiment “bordering on hysteria.” Silent Spring, meanwhile, had yet to reach the book stores.

________________________________________________

Method & Message

Book and Author

Rachel Carson began Silent Spring with a short two-page “Fable for Tomorrow,” describing a fictional pastoral place of productive farm fields, fish-filled streams, and abundant wildlife. But this bucolic scene is suddenly and mysteriously transformed into a desolate place, as Carson describes:

“…There was once a town in the heart of America where all life seemed to live in harmony with its surroundings… Then a strange blight crept over the area and everything began to change… There had been several sudden and unexplained deaths, not only among adults, but even among children… There was a strange stillness… The birds for example – where had they gone?… On the farms the hens brooded, but no chicks hatched… Anglers no longer visited [the streams], for all the fish had died… [A] white granular power still showed a few patches; some weeks before it had fallen like snow upon…the fields and streams…”

|

“Elixirs of Death” “For the first time in the history of the world, every human being is now subjected to contact with dangerous chemicals, from the moment of conception until death. In the less than two decades of their use, the synthetic pesticides have been so thoroughly distributed throughout the animate and inanimate world that they occur virtually everywhere. They have been recovered from most of the major river systems and even from streams of groundwater flowing unseen through the earth. Residues of these chemicals linger in soil to which they have been applied a dozen years before. They have entered and lodged in the bodies of fish, birds, reptiles, and domestic and wild animals so universally that scientists carrying on animal experiments find it almost impossible to locate subjects free from such contamination. They have been found in fish in remote mountain lakes, in earthworms burrowing in the soil, in the eggs of birds — and in man himself. For these chemicals are now stored in the bodies of the vast majority of human beings, regardless of age. they occur in mother’s milk, and probably in the tissues of the unborn child…” |

This description, Carson told her readers, was indeed fictional, but the very damages described in the fable had actually occurred in separate instances all across America. Carson then went about showing her readers, chapter-by-chapter, “what has already silenced the voices of spring in countless towns in America.” She proceeded to show how pesticides were taking their toll on air, land and water, birds and fish, farmers and farmworkers, and public health. Her chapter titles pointed the way, and some did not mince words. They included, for example: “Elixirs of Death”(excerpt at right), “Surface Waters and Underground Seas,” Realms of The Soil,” “Earth’s Green Mantle,” “Needless Havoc,” “And No Birds Sing,” Rivers of Death,” Indiscriminately From The Skies,” “The Human Price,” “The Rumblings of An Avalanche,” and more.

She showed how insufficiently tested pesticides were being widely released into the environment, killing hundreds or even thousands of beneficial species; how the chemicals concentrated or “bio-magnified” through the food chain from plants and earthworms to birds, fish, and larger predators. Carson also showed that the progression in chemical making had gone well beyond pesticidal substances made from minerals in earlier times, and were now man-made substances that were chemically synthesized in the laboratory, and that this might be a problem for the biological world and the human body:

…The chemicals to which life is asked to make its adjustment are no longer merely the calcium and silica and copper and all of the rest of the minerals washed out of the rocks; . . . they are the synthetic creations of man’s inventive mind, brewed in laboratories, and having no counterpart in nature. To adjust to these chemicals would require time on the scale that is nature’s; it would require not merely the years of a man’s life, but the life of generations. And even this, were it by some miracle possible, would be futile, for the new chemicals come from our laboratories in an endless stream; almost five hundred annually find their way into actual use in the United States alone [Note: today it’s more like 1,000s annually]. The figure is staggering and its implications are not easily grasped—500 new chemicals to which the bodies of men and animals are required somehow to adapt each year, chemicals totally outside the limits of biologic experience…

Still, Carson was careful to say early on in her book, and often repeated in later public appearances, “it is not my contention that chemical insecticides may never be used. I do contend that we have put poisonous and biologically potent chemicals indiscriminately into the hands of persons largely or wholly ignorant of their potentials for harm…”

1962: Rachel Carson with microscope on porch at her home in Silver Spring, Maryland.

In Chapter 8 – “And No Birds Sing” – Carson included the story how DDT spraying of elm trees on the campus of Michigan State University in the mid-1950s to fight Dutch Elm disease was also killing a large number of robins. That spraying was aimed at eradicating the bark beetle which spread Dutch Elm disease. However, the trees’ DDT-coated leaves fell to earth, where they were eaten by earthworms who absorbed the DDT. The worms in turn, were eaten by the robins, a number of which died of DDT poisoning.

Similarly, in Chapter 9 – “Rivers of Death” – Carson used the Miramachi River of New Brunswick Canada to show how a DDT spraying to protect balsam forests from the spruce budworm also killed the aquatic insects that young salmon fish in the river depended upon for food. So then by Chapter 12 – “The Human Price” – she then describes the larger biological systems that society depends upon, she writes:

…For each of us, as for the robin in Michigan, or the salmon in the Miramichi, this is a problem of ecology, of interrelationships, of interdependence. We poison the caddis flies in the stream and the salmon runs dwindle and die. . . . We spray our elms and following springs are silent of robin song, not because we sprayed the robins directly but because the poison traveled, step by step, through the now familiar elm leaf-earthworm-robin cycle. These are matters of record, observable, part of the visible world around us. They reflect the web of life-or death-that scientists know as ecology…

All in all, Carson’s book was, and still is with few exceptions, a taut 260 pages of reporting with engaging stories, some from everyday people who were dealing with chemical problems in their communities to which Carson would add scientific information and/or further explanation. Her book also had plenty of documentation, with nearly 30 pages of mostly scientific citations to support her reporting.

_________________________________________________

Publication & Reviews

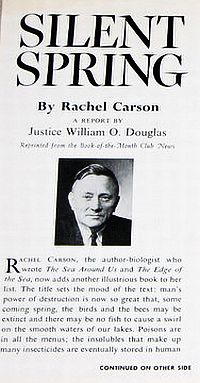

Book-of-the-Month Club edition of “Silent Spring” included a “report” insert by Supreme Court justice, William O. Douglas.

Silent Spring had also been selected by the Book-of-the-Month Club for October 1962, which meant at least another 150,000 copies in sales. Book-of-the-Month-Club selection also meant that Silent Spring would reach rural and Main Street America, an audience well beyond those who read The New Yorker. The Book Club edition also included a special “report” from U.S. Supreme Court Justice, William O. Douglas introducing the volume.

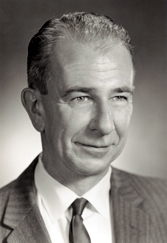

As Silent Spring arrived in book stores that fall, more news stories and book reviews appeared. CBS television newsman, Eric Sevareid, who would later host and narrate a TV show on the book, published a piece in the Los Angeles Times on September 23rd entitled, “Pests vs. Men: The Big Battle Is Raging Again; Is Pesticide Use Tinkering With Nature Balance?”

Other publicity on the book included a positive editorial in The New York Times. Excerpts of the book were also published in the National Audubon Society’s magazine, Audubon, as well as various newspapers and magazines. Her book was attacked as “biased,” “emotional” and “alarmist.” Others called it a hoax, science fiction, and in a league with “The Twilight Zone” TV show. Carson herself was labeled a communist, hysterical woman, a nature nut, and worse. A Chicago Daily News review stated: “…Silent Spring may well be one of the great and towering books of our time. This book is must reading for every responsible citizen.” But not all the reviews and publicity were glowing.

In fact, critical reviews appeared in popular mainstream magazines of the day, including Time, Newsweek, Life, and The Saturday Evening Post. One Time magazine review of September 28, 1962 deplored Carson’s “oversimplifications and downright errors…Many of the scary generalizations–and there are lots of them–are patently unsound.” Another late September 1962 review by Edwin Diamond appearing in the Saturday Evening Post, stated: “Thanks to an emotional, alarmist book called ‘Silent Spring,’ Americans mistakenly believe their world is being poisoned.” In Chemical & Engineering News of October 1, 1962, under the title, “Silence, Miss Carson,” Dr. William J. Darby, a nutritionist at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, wrote: “Her ignorance or bias on some of the considerations throws doubt on her competence to judge policy.” Darby suggested that the public could be misled by Carson’s book. He also added at the end of his review: “The responsible scientist should read this book to understand the ignorance of those writing on the subject and the educational task which lies ahead.”

Monsanto’s “Desolate Year” insect plague story, was sent out to thousands of reviewers, editors and journalists to counter “Silent Spring.”

The chemical industry, meanwhile, had been planning their fight against Carson and book even before The New Yorker series had appeared, as word of the book had leaked out early on. Through the summer and fall of 1962, the chemical industry continued its attacks on the book and Carson. The National Agricultural Chemical Association (NACA) doubled its budget and distributed thousands of copies of negative book reviews for Silent Spring, and also issued warnings to newspaper and magazine editors that favorable reviews of the book could result in diminished advertising revenue. NACA reportedly spent more than $250,000 in their campaign against the book. The Monsanto Chemical Co. published a short story titled “The Desolate Year” – an answer to Carson’s “Fable for Tomorrow” chapter. In the Monsanto version, the failure to use pesticides results in an insect plague that devastates America. Five thousand copies of “The Desolate Year” were sent out to book reviewers, science and gardening writers, magazine editors, and farm journalists. “This was, for us,” said one Monsanto man, “an opportunity to wield our public relations power.”

Monsanto was one of the chemical companies to actively campaign against “Silent Spring.”

In the chemical industry, a few scientists became especially visible in the attack on Silent Spring. One scientist from American Cyanamid, Robert White-Stevens, stated: “If man were to follow the teachings of Miss Carson, we would return to the Dark Ages, and the insects and diseases and vermin would once again inherit the earth.” White-Stevens made 28 such speeches by the end of 1962, charging, among other things, that Silent Spring was “littered with crass assumptions and gross misrepresentations” and that Carson was “a fanatic defender of the cult of the balance of nature.”

Another former Cyanamid chemist, Thomas Jukes, also became a critic of Carson and Silent Spring. George C. Decker, an entomologist at the Illinois Natural History Survey and Illinois Agricultural Experiment Station who had been a frequent consultant to the chemical industry, called the book a “hoax” and “science fiction,” to be read, he said, “in the same way that the TV program ‘Twilight Zone’ is to be watched.” Other attacks on Carson were more personal, questioning her character or her mental stability; some called her a communist, an hysterical woman, a nature nut, and more.

LaMont Cole of Cornell gave an important positive review of "Silent Spring” in Scientific American magazine.

By year’s end 1962, and after less than three months on the market, Silent Spring had sold well over 100,000 copies and continued to appear on the New York Times’ bestsellers list, where it would remain for 31 weeks. In addition, in state legislatures by that date more than 40 bills had been introduced aimed at governing the use of pesticides. But the fight over pesticide policy in Washington, D.C. was just beginning. In 1963, Carson and Silent Spring would receive still more national attention and some important affirmation.

CBS Reports

Sample “CBS Reports” title card screenshot

Eric Sevareid, who became a notable newsman in his own right, hosted the April 1963 show on “Silent Spring.”

Rachel Carson being interviewed at her home by CBS correspondent Eric Sevareid.

“It is the public that is being asked to assume the risks,” she said at one point. “The public must decide whether it wishes to continue on the present road, and it can do so only when in full possession of the facts….” She further explained that “we still talk in terms of conquest. We still haven’t become mature enough to think of ourselves as only a tiny part of a vast and incredible universe.” Man’s attitude toward nature, she continued, “is today critically important simply because we have now acquired a fateful power to alter and destroy nature…”

Rachel Carson on “CBS Reports,” 1963.

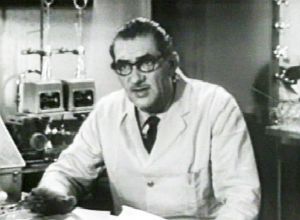

Robert White-Stephens of the American Cyanamid Co. as he appeared on “CBS Reports,” April 1963.

“When pesticides, registered pesticides, are used in accordance with label instructions and recommendations, then there is no danger to either man or to animals and wildlife,” he stated at one point. Of Carson and her book he said:

“The major claims in Miss Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring, are gross distortions of the actual facts, completely unsupported by scientific experimental evidence and general practical experience in the field. If man were to faithfully follow the teachings of Miss Carson, we would return to the Dark Ages, and the insects and diseases and vermin would once again inherit the Earth.”

White House report on pesticides of May 15, 1963 helps vindicate Rachel Carson.

Several weeks later, on May 15, 1963, Carson and Silent Spring received further affirmation when the President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) released a report entitled, “The Use of Pesticides.”

The PSAC report, which had been instigated in part by Silent Spring, and reportedly urged along by President Kennedy, was the result of eight months of wrangling by the government’s top scientists and regulators, who held a series of meetings with Carson, industry representatives, and Department of Agriculture officials.

The PSAC report concluded that while pesticides were scrutinized thoroughly for their agricultural effectiveness, they generally were not given the same level of review for environmental and public safety. And for many pesticides in use, the PSAC report found there was little knowledge of chronic effects over a lifetime.

The report also acknowledged that “until publication of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson, people were generally unaware of the toxicity of pesticides.” The PSAC report recommended that pesticide residues be tracked and monitored in the environment – in air, water, soil, fish, wildlife, and humans. Importantly, the report also stated that “elimination of the use of persistent toxic pesticides should be the goal.”“Until publication of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson, people were generally unaware of the toxicity of pesticides.”

– PSAC Report, 1963.

On the day following the report’s release, the headline in The Christian Science Monitor newspaper declared, “Rachel Carson Stands Vindicated!” In that evening’s CBS news telecast, commentator Eric Sevareid referring to the report, said that Carson had succeeded in her stated goals, one of which was “to build a fire under the government.” Dan Greenberg, writing for Science magazine, found the PSAC report to be a temperate document, carefully balanced in its assessments of risks versus benefits, but that it “adds up to a fairly thorough-going vindication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring thesis.…” Greenberg added that “Carson can be legitimately charged with having exceeded the bounds of scientific knowledge for the purpose of achieving shock; but her principal point—that pesticides are being used in massive quantities with little regard for undesirable side effects—permeates the PSAC report and is the basis for a series of recommendations…”

Before Congress

June 1963: Rachel Carson testifying, U.S. Senate.

In her appearances before the two committees, Carson generally called for establishment of a “pesticide commission” or some type of independent regulatory agency to protect people and the environment from chemical hazards. In her testimony, Carson asserted that one of the most basic human rights was the “right of the citizen to be secure in his own home against the intrusion of poisons applied by other persons.” In her appearance at Senator Ribbicoff’s hearings, Carson called for strict control of aerial pesticide spraying, reduction and eventual elimination of the use of persistent pesticides, and more research devoted to non-chemical methods of pest control.

Some of what Carson had to say before the Senate Commerce Committee on June 6th is offered below in rough transcription:

“…The most disturbing of all such reports however concerns the finding of DDT in the oil of fish that live far out at sea… Oil from some of these marine fish contains DDT in concentrations exceeding 300 parts per million… All this gives us reason to think deeply and seriously about the means by which these residues reach the places where we are now discovering them… No one can answer this question with complete assurance…Upper atmosphere may be carrying chemical particles and the pesticide contamination of such remote places may be the result of a new kind of fallout…. If we are ever to solve problem of contamination we must begin to count the many hidden costs of what we are doing…A strong and unremitting effort must be made to eliminate pesticides that leave residues…No other way to control rapidly spreading contamination…”

Rachel Carson, 1963 hearings.

Carson’s appearances before the congressional committees were among her last in public. In December 1963, she received some national recognition with her induction into the American Academy of Arts and Letters and she also received the National Audubon Society Medal.

By the close of 1963, the more vitriolic attacks on Silent Spring had begun to subside. The book was now available in paperback editions, adding to its circulation. However, in Carson’s personal life she was losing her battle with cancer. On April 14, 1964, less than a year after she had testified before Congress, Rachel Carson died in Silver Spring, Maryland. She was 56 years old. Carson biographer, Linda Lear, has noted one poignant story about Carson in her final days:…Shortly before her death, Sierra Club director David Brower played host to Carson in California, fulfilling a dream of hers to visit Muir Woods and see the Pacific Ocean. Brower recalls that he took Carson down to the shore at Rodeo Lagoon where he first gave her several handfuls of Pacific beach sand which she examined minutely commenting on the different colored crystals. Then as Brower pushed Carson in her wheelchair around a beach cove they came upon the biggest flock of brown pelicans he had ever seen. The birds had only recently been near extermination. Brower later said it was as if the pelicans were there that day to thank Carson…

Carson’s funeral service was held in Washington, D.C.’s National Cathedral and among her pallbearers were Stewart Udall, U.S. Secretary of the Interior and U.S. Senator Abraham Ribicoff.

Only weeks before Carson’s death, the U.S. Public Health Service had announced that the periodic huge fish kills on the lower Mississippi River over the previous four years had been traced to toxic ingredients in three kinds of pesticides. The chemicals had drained into the river from neighboring farm lands. Yet even today, more than 50 years after Carson’s warnings, there is still abundant evidence of chemical toxicity in the environment and beyond. In recent years, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia has been tracking chemicals found in human blood and urine. The Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals, for example, issued in 2009, measured some 212 chemicals in humans, 75 of which CDC measured for the first time.

Rachel Carson’s Legacy

1961. Rachel Carson at the seashore. Life photo; A. Eisenstaedt.

Although birds and wildlife were a prominent focus in Silent Spring, Carson made clear the connection between what happens in the environment and all of life – all the way to humans. Moreover, Carson was the first to signal, in a popular way, a new kind of pollution, the unseen kind; the chemical toxicity that could infiltrate biology at the cellular and molecular levels, and along with it, bring cumulative and generational harms to birds, fishes and us. Carson’s ecological tableaus showed that “we’re- all-in-this-together;” that the fate of beneficial insects was also our fate. Silent Spring “set the table” as well for a new kind of thinking about the environment, so that soon-to-come major incidents such as the burning of the Cuyohaga River, the Santa Barbara oil spill, and recurring smog alerts would each add weight and galvanizing force to embedding a more permanent environmental ethic in society. And by linking environmental and human health in her story, Carson helped elevate the political standing of environmental issues; she helped popularize and politicize environmentalism.

Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” helped create the EPA in 1970.

In 1972, Paul Brooks, Carson’s editor at Houghton Mifflin published The House of Life: Rachel Carson at Work. In July 1973, CBS rebroadcast its 1962 CBS Reports TV show, “The Silent Spring Of Rachel Carson.” By June 1980, President Jimmy Carter awarded Rachel Carson the Presidential Medal of Freedom, inscribed in part: “…she created a tide of environmental consciousness that has not ebbed.” The following year, a Rachel Carson postage stamp was issued in her honor, part of the Great Americans Series.

1981: Rachel Carson stamp.

A number of conservation areas, trails, schools, and landmarks have been named in Carson’s honor – a 650 acre conservation park in Montgomery County, Maryland; a bridge in Pittsburgh; an estuary in North Carolina; an elementary school in Sammamish, Washington; among others.

In 1993, the documentary “Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring,” was produced for the PBS American Experience series, with actress Meryl Streep narrating the voice of Carson. And through the 1990s, several books on Carson appeared, including Linda Lear’s 1997 biography, Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature.

DVD cover for 1993 PBS TV special, “Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring,” in the American Experience series. Click for DVD.

Silent Spring, meanwhile, may never be out of print, and certainly in e-book form it will likely travel well into the future. Print copies, nonetheless, continue to sell at a rate of about 20,000 or so a year. The book has been included on a number of lists compiling the “100 most influential books of the 20th century,” and Carson has been named to various lists of “most influential people,” including Time magazine’s “100 Most Influential People of the 20th Century.”

In 1993, when PBS ran its American Experience TV show on Rachel Carson, historian David McCollough’s introduction summed up Carson’s impact: “A single book changes history only rarely. There was Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, and Ralph Nader’s Unsafe at Any Speed. And then there was Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. . . Rachel Carson changed our lives, changed the way we think about the world and our place in it.”

Also of interest at this website may be the story profiling Union Carbide pesticide advertising in the 1960s, which also tells a larger story about toxic chemicals and the horrific 1984 Bhopal, India toxic gas catastrophe there, as well as related leaks in West Virginia. See also “Environmental History,” a topics page with additional stories on air pollution, oil spills, river pollution, strip mining, and other issues. For stories on “Print & Publishing,” please visit that category page or go to the Home Page for further choices. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 22 February 2012

Last Update: 20 February 2024

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/PopHistoryDig

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Power in the Pen, Silent Spring: 1962,”

PopHistoryDig.com, February 21, 2012.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“Rachel Carson Papers,1921-1989,” Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

“The Life & Legacy of Rachel Carson,” Rachel Carson.org.

“Rachel Carson,” Wikipedia.org.

Rachel L. Carson, Under The Sea-Wind, New York: Oxford University Press, 1941.

Edwin Way Teale, “DDT: It Can Be a Boon or a Menace,” Nature Magazine, March 1945

“The Sea Around Us,” Wikipedia.org.

Rachel Carson, “Why Our Winters Are Getting Warmer,” Popular Science, November 1951 (excerpt from Carson’s The Sea Around Us, about ocean currents and climate).

Rachel Carson, “The Edge of the Sea” (excerpts from earlier book, Under The Sea Wind), Life, April 14, 1952, pp. 64-68.

“New Elite of American Naturalists Heirs of a Great Tradition,” Life, December 22, 1961, p. 103.

“Pollution May Kill Us, Marine Biologist Warns; Rachel Carson Declares Man May Destroy Himself by His Vast Assortment of Wastes,”Los Angeles Times, June 13, 1962, p. A-2.

Rachel Carson, A Reporter at Large, “Silent Spring,” The New Yorker, June 16, 1962, pp, 35-40.

Rachel Carson, A Reporter at Large,”Silent Spring,” The New Yorker, June 23, 1962, pp. 31-36.

Rachel Carson, A Reporter at Large, “III-Silent Spring,” The New Yorker, June 30, 1962, pp. 35-42.

Editorial, “The Chemicals Around Us,” Chemical Week, July 14, 1962, p. 5.

John M. Lee, “‘Silent Spring’ is Now Noisy Summer; Pesticides Industry Up In Arms Over a New Book; Rachel Carson Stirs Conflict — Producers Are Crying ‘Foul’,” New York Times, July 22, 1962.

“Nature is for the Birds,” Chemical Week, July 28, 1962, p. 5.

“Reponse to Criticism,” Chemical Week, August 11, 1962, p. 42.

Thomas Jukes, “A Town in Harmony,” Chemical Week, August 18, 1962, p. 5.

Louis Cassels, “Man’s Struggle Against Pests May Endanger Life; New Book Stirs Controversy Over Use of Insecticides to Protect Trees, Plants,” Los Angeles Times, August 19, 1962, p. E-8.

Val Adams, “‘C.B.S. Reports’ Plan a Show On Rachel Carson’s New Book,” New York Times, August 30, 1962, p. 42.

Marjorie Hunter, “U.S. Sets Up Panel to Review The Side Effects of Pesticides; Controls Studied–Kennedy Finds Work Spurred by Rachel Carson Book,” New York Times, August 31, 1962, p. 9.

Nate Haseltine, “Experts Studying Pesticide Dangers To Man, Wildlife,” Washington Post / Times Herald, September 1, 1962, p. A-4.

“Are We Poisoning Ourselves?,” Business Week, September 8, 1962, pp. 36-38.

Brooks Atkinson, Critic at Large, “Rachel Carson’s Articles on the Danger of Chemical Sprays Prove Effective,” New York Times, September 11, 1962, p. 30.

“Rachel Carson Book Is Called One-Sided,” New York Times, September13, 1962.

Walter Sullivan, “Chemists Debate Pesticides Book; Industry Fears Public Will Turn Against Its Products,” New York Times, September 13, 1962, p. 34.

“Monsanto Dissects Pesticide Criticism,” New York Times, September 22, 1962.

Eric Sevareid, “Pests vs. Men: The Big Battle Is Raging Again; Is Pesticide Use Tinkering With Nature Balance?,” Los Angeles Times, September 23, 1962, p. F-2.

Lorus and Margery Milne, “There’s Poison All Around Us Now; The Dangers in the Use of Pesticides Are Vividly Pictured by Rachel Carson,” The New York Times Book Review, September 23, 1962.

“Bird Haven Spurs a Pesticide War; Spray Casualties Brought Book That Caused Furor,” New York Times, September 23, 1962.

“Pesticides: The Price for Progress,” Time, September 28, 1962, pp. 45-48.

I.L. Baldwin, “Chemicals and Pests,” Science, September 28, 1962, pp.1042-1043.

Loren Eiseley, “Using a Plague to Fight a Plague,” Saturday Review, September 29, 1962, pp. 18-19, 24.

William Vogt, “On Man the Destroyer,” Natural History, September 1962, pp. 3-5.

Letters to the Editor (response to Silent Spring review), Time, October 5, 1962.

William J. Darby, “Silence, Miss Carson” (Book Review), Chemical & Engineering News, October 1, 1962, pp. 60-63.

“The Desolate Year,” Monsanto Magazine, October 1962, pp. 4-9.

“Bracing for Broadside,” Chemical Week, October 6, 1962, p. 23.

“The Gentle Storm Center: Calm Appraisal of Silent Spring,” Life, October 12, 1962, pp.105-106.

Ovid A. Martin, “Agriculture Defends Use Of Chemicals,” Washington Post/Times Herald, Octo-ber 19, 1962, p. A-7.

“Review of Silent Spring,” The Economist (London), October 20,1962, pp. 248-251.

Robert L. Rudd, “The Chemical Countryside: A View of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring,” Pacific Discovery (California Academy of Sciences), Nov-Dec 1962, pp.10-11.

LaMont C. Cole, “Rachel Carson’s Indictment of the Wide Use of Pesticides” (Silent Spring Book Review), Scientific American, December 1962, pp.172-180.

Jean M. White, “Rachel Carson Hints Industry Filters Facts,” Washington Post / Times Herald, De-cember 6, 1962, p. A-13.

“The Furor Over Pesticides,” Senior Scholastic, December 12, 1962.

Robert C. Toth, “Pesticides Study Found Difficult; U.S. Panel Trying to Assess Chemical Perils to Body, But the Facts Are Few; Poisons Work Subtly; Dangers in Compounds Must Be Scaled Against Their Benefits, Expert Says,” New York Times, December 7, 1962, p. 41.

Clarence Cottam, “A Noisy Reaction to Silent Spring,” Sierra Club Bulletin, January 1963, pp. 4-5,14-15.

John Davy, Weekend Review, “Menace in the Silent Spring,” The Observer (U.K.), February 17, 1963, p. 21.

Val Adams, “2 Sponsors Quit Pesticide Show; Withdraw From TV Report on ‘Silent Spring’ Book,” New York Times, April 3, 1963, p. 95.

Jack Gould, “TV: Controversy Over Pesticide Danger Weighed; ‘C.B.S. Reports’ Gives Both Sides of Dispute ‘Silent Spring’ Author Answers Her Critics,” New York Times, April 4, 1963, p. 95.

The Paley Center for The Media (video), The Silent Spring of Rachel Carson, CBS Reports, 1963 (show is offered in three video segments).

Daniel S. Greenberg, “Pesticides: White House Advisory Body Issues Report Recommending Steps to Reduce Hazard to Public,” Science, May 24, 1963, pp. 878-879.

The White House, “Use of Pesticides,” Report of The President’s Science Advisory Committee, Washington, D.C., May 15, 1963, JFKlibrary.org.

“Pests and Poisons: Rachel Carson Before Senate Investigative Subcommittee,” Newsweek, June 17, 1963, p. 86.

“Biology: The Pest-Ridden Spring,” Time, Friday, July 5, 1963.

Rachel Carson, “Rachel Carson Answers,” Audubon, September 1963, pp. 262-265.

E. Diamond, “The Myth of the ‘Pesticide Menace’,” Saturday Evening Post, September 28, 1963, pp.16, 18.

“Rachel Carson Dies of Cancer; ‘Silent Spring’ Author Was 56,” New York Times, April 15, 1964.

Bruce H. Frisch, “Was Rachel Carson Right?,” Science Digest, August 1964, pp. 39-45.

Frank Graham, Jr., Since Silent Spring, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970.

K.S. Davis, “The Deadly Dust: The Unhappy History of DDT,” American Heritage, February 1971, pp. 44-47.

“Silent Spring,” Wikipedia.org.

“The Story of Silent Spring,” NRDC.org.

Paul Brooks, The House of Life: Rachel Carson at Work, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1972.

Frank Graham, Jr., “Rachel Carson,”EPA Journal, November/December, 1978.

Cathy Trost, Elements of Risk: The Chemical Industry and its Threat To America, New York: Times Books, 1984.

“‘Silent Spring’; A Plea From 1962,” New York Times, October 11, 1987.

Jules Janick, History of Horticulture, Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Purdue University, Reading 31-3: “Rachel Carson, Silent Spring, and the Environmental Movement,”

Patricia H. Hynes, “Unfinished Business: `Silent Spring’ on the 30th Anniversary of Rachel Carson’s Indictment of DDT, Pesticides Still Threaten Human Life,” Los Angeles Times, September 10, 1992.

Linda J. Lear, “Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring,” Environmental History Review, Summer 1993, pp. 23-48.

Linda Lear, Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature, New York: Holt & Co., 1997.

Linda Lear, Chapter One: “Wild Creatures Are My Friends,” Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature, at WashingtonPost.com.

Bill McKibben, “A Voice For the Wilderness” ( Review of Linda Lear’s Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature),Washington Post, Sunday, September 14, 1997.

Peter Matthiessen, “Environmentalist Rachel Carson, Time, Monday, March 29, 1999.

Michael Lipske, “How Rachel Carson Helped Saved the Brown Pelican,” National Wildlife, December 1, 1999.

Rachel Carson, Lost Woods: The Discovered Writing of Rachel Carson, Boston: Beacon Press, 1999.

Craig Waddell, Paul Brooks and Linda Lear, And No Birds Sing: Rhetorical Analyses of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000.

“Rachel Carson and the Fish and Wildlife Service,” FWS.gov.

“Rachel Carson at the MBL,” Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

“Rachel Carson (1907-1964),” Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge, Northeast Region, National Wildlife Refuge System, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Rachel Carson Institute, Chatham College.

“Rachel Carson: Other Resources,” Jennie King Mellon Library, Chatham College.

Commemorating Carson, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Silent Spring of Rachel Carson, SilentSpring Movie.com.

John H. Cushman, Jr., “After ‘Silent Spring,’ Industry Put Spin on All It Brewed,” New York Times, March 26, 2001.

Arlene Rodda Quaratiello, Rachel Carson: A Biography, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004, 138 pp.

Jack Doyle, Trespass Against Us: Dow Chemical & The Toxic Century, Monroe, Maine: Common Courage Press, 2004.

Priscilla Coit Murphy, What a Book Can Do: The Publication and Reception of Silent Spring, University of Massachusetts Press, 2005 – 254 pages

Booklist Center, “100 Best Nonfiction Books of the Twentieth Century,” National Review, 2005.

“100 Most Influential Books of The Century,” Boston Public Library, 2005.

Douglas Allchin, “Historical Simulation, Debating Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, The President’s Advisory Committee on Pesticides, UMN.edu, 2006-2009.

Mark H. Lytle, Gentle Subversive: Rachel Carson, Silent Spring, and the Rise of the Environmental Movement, Oxford University Press, 2007, 288pp.

“Rachel Carson 100th Birthday: ‘Mother’ of Environmentalism Celebrated,” Washington Post, March 7, 2007.

Linton Weeks, “The CBS Report That Helped ‘Silent Spring’ Be Heard,” Washington Post, Wednesday, March 21, 2007, p. C-1.

Deborah G. Scanlon, “Summers in Woods Hole Spur Rachel Carson’s Love of Ocean,” Falmouth Enterprise, June 8, 2007.

Linda Lear, “Rachel Carson and the Awakening of Environmental Consciousness,” George Washington University.

Christian H. Krupke, Renée Priya Prasad, and Carol M. Anelli, “Professional Entomology and the 44 Noisy Years Since Silent Spring,” Part 2: Response to Silent Spring, American Entomologist, Spring 2007, pp. 16-26.

“Rachel Carson,” Bill Moyers Journal, PBS.org, September 2007.

Thalia Assuras, “The Price Of Progress” (video), CBSNews.com, September 19, 2007 ( video on Rachel Carson’s impact, with footage of early spraying and excerpts from 1963 “CBS Reports” show; run time: 9:43).

Frank Graham, Jr., “Nature’s Protector and Provocateur,” Audubon, Sept-Oct 2007.

Peter Matthiessen (ed.), Courage for the Earth: Writers, Scientists, and Activists Celebrate the Life and Writing of Rachel Carson, Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2007, 208 pp.

“DDT Blast from the Past: 1951,” Millard Fillmore’s Bathtub, May 16, 2008.

Lisa H. Sideris and Kathleen Dean Moore (eds), Rachel Carson: Legacy and Challenge, Albany: Statue University of New York Press, 2008, 287 pp.

“Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and the Beginning of the Environmental Movement in the United States,” Indiana.edu.

Jamin Creed Rowan, “The New York School of Urban Ecology: The New Yorker, Rachel Carson, and Jane Jacobs,” American Literature, Volume 82, Number 3, 2010, Duke University Press, pp. 583-610.

A. Macgillivray, Understanding Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Rosen Publishing, 2010, 128pp.

_____________________________________