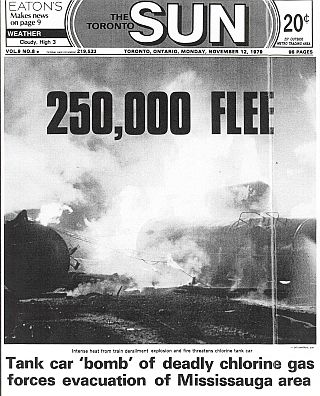

Front page of “The Toronto Sun” for November 12, 1979, with headline, photo & caption describing the fiery train wreck, toxic gas dangers, and major evacuation at Mississauga, Ontario.

First, in Chatham, Ontario it stopped to pick up additional rail cars from another train coming in from Sarnia, Ontario, a major oil and petrochemical center, with refineries and chemical plants.

Tank cars added to train No. 54 that afternoon from chemical plants were carrying caustic soda, propane, chlorine, styrene, and toluene. Among the additional cars from Sarnia were two chlorine tankers from Dow Chemical’s plant there. The train was now 106 cars long.

Train No, 54 left Chatham about 6 p.m. and headed northeast to its next stop at London, Ontario where it made a crew change.

Thereafter, as the train resumed its run toward Toronto, unbeknownst to anyone on the train, one of its cars was having a problem.

As the train rumbled past Milton, still southwest of Toronto by some 40 kilometers and traveling at about 60 miles per hour, friction had built up in an axle wheel-bearing on Car 33. It was one of the train’s older cars — an old-fashioned type needing manual lubrication for its axle box.Car 33 sent its glowing hot wheels flying off the train and crashing through a fence, landing in the backyard of a nearby home. Newer, more modern cars had roller bearings.

Friction and heat continued to build as the train moved down the line. Residents living near the tracks later reported seeing smoke and sparks coming from the middle section of the train. Further on, others would later report that part of the train appeared to be on fire. As the train continued on its journey, the axle heat built up to the point where the axle on Car 33 broke off. Then the car started to break apart. At the Burnhamthorpe Road crossing, Car 33 sent its glowing hot wheels flying off the train and crashing through a fence, landing in the backyard of a nearby home.…The damaged tank car, with its dangling undercarriage, left the tracks; 23 other cars followed, causing a deafening crash as explosions and fireballs lit up the sky… It was now nearing midnight as the train – still on the tracks – approached Mississauga, a Toronto suburb of about 300,000 people.

The train sped past an area of apartment buildings and suburban homes, now carrying the dangling and damaged undercarriage of Car 33. Just past a light industrial area, at the Mavis Road crossing, the damaged tank car with its dangling undercarriage, left the tracks. Twenty-three other cars followed it off the tracks, causing a deafening crash and metal-on-metal grinding sound as the iron and steel cars collided and twisted into a tangled pile. At that point, some propane cars burst into flames. Other tankers began spilling their chemical contents, initially styrene and toluene. Within seconds, the leaked liquids and vapors ignited, causing a massive explosion and fireball.

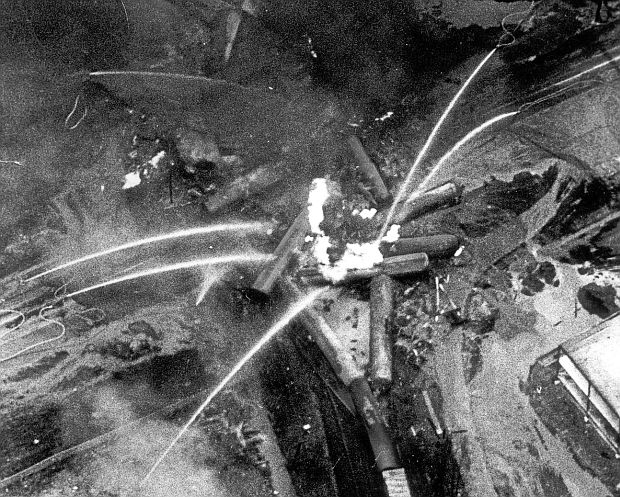

Photo of one of the explosions at Mississauga, Ontario, following November 1979 train derailment of Canadian Pacific Railway freight train with 106 cars, a number of which carried toxic and volatile chemicals.

Yellow-orange flames leapt to 1,500 meters (5,000 feet) in the sky and could be seen 100 kilometers away. Soon the fire was being fed by the contents of the other wrecked tank cars, with more in danger—eleven held propane, four had caustic soda, three contained styrene, three more held toluene, two box cars were filled with fiberglass insulation, and one contained chlorine. An undamaged portion of the train, still on the track, had been uncoupled with the heroic efforts of 27 year-old trainman, Larry Krupa, who braved fire and explosion to reach undamaged car No. 32 to close an air brake angle spigot that enabled the release of 26 cars from the wreck, as that section of the train then pulled forward, away from the derailment and fire.

Rising fireball from a burning Canadian Pacific rail car in Mississauga, Ontario after derailment in November 1979.

But just as firefighters were about to begin their battle—now early Sunday morning—a violent explosion occurred as another of the propane tank cars blew up.

The blast knocked police, firefighters, and onlookers to the ground, showering the surrounding area with chunks of metal.

Windows were shattered throughout the area, and three greenhouses and a municipal recreational building were destroyed. Near the explosion, a green haze was seen drifting in the air.

Minutes later, a second explosion occurred. In another propane car, a “bleve” occurred—a boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion—hurling the tank car into the air, spewing fire as it went, finally tumbling into a cleared field more than 600 meters away. Five minutes later, another bleve occurred, sending one end of the propane tank car about 65 meters away.

Emergency authorities and public officials from several governmental levels were being summoned to the scene by this time, as police and fire officials tried to acquire the train’s cargo manifest and emergency procedures. However, the main manifest was in the front part of the train which by then had moved on to Cooksville, about six kilometers away.

About an hour later, around 1:30 a.m., a readable copy of the manifest was delivered to emergency officials. Checking the serial numbers of derailed cars, they soon determined the cars held a mixed cargo of dangerous chemicals, including chlorine, posing a possible poison gas threat.

Scene at Mississauga train derailment, November 1979. General view of burning tanking cars from about a half mile away. Frank Lennon/Toronto Star

Chlorine, a deadly chemical, forms a greenish-yellow cloud when released and hovers close to the ground. A chlorine cloud will follow the terrain as it drifts and disperses—a feature that made it an ideal weapon in the trench warfare of WWI. Once chlorine gas is breathed, it saps the fluids in the linings of lungs and blood, and starts a chain reaction that ends with slow suffocation. At the wreck site, a chlorine tanker was close to a filled propane tanker, in danger of exploding, but the ongoing fire prevented an initial assessment. However, it was later determined that the chlorine tanker had been punctured and was leaking.

In Mississauga, meanwhile, the fire chief ordered 3,500 residents living closest to the derailment to evacuate. Police officers using loud bullhorns and knocking on doors alerted sleepy residents. Later, as winds shifted and more information about the train’s cargo became known, the area of evacuation was expanded. Shortly after 2 a.m., Metropolitan Toronto Police sent sound trucks to alert residents of the broader evacuation. The local Canadian Red Cross began setting up resident evacuation centers—one at Square One, a large covered shopping center about 2.5 kilometers from the derailment. Calls went out for ambulances in the surrounding area and buses were also summoned from the Toronto, Oakville, and Mississauga transit authorities.

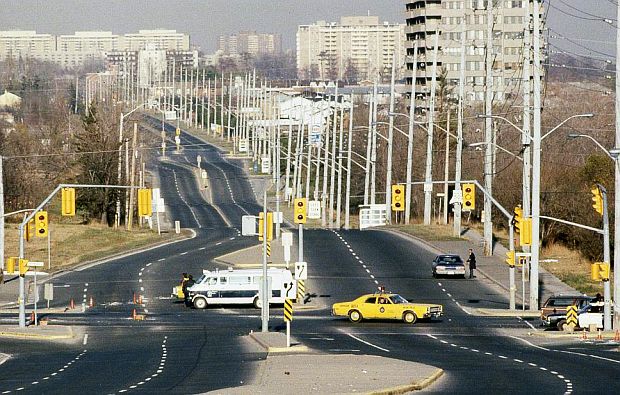

Looking down roadway at Mississauga, Ontario into the train wreck scene where derailed chemical tankers and other Canadian Pacific rail cars were blazing as firefighters did their best to quell multiple infernos

A team of experts from Dow Chemical at Sarnia, owners of the chlorine tank car, arrived on the scene armed with specialized equipment to execute something called CHLOREP, the chlorine emergency plan. Dow’s Stu Greenwood headed up this effort. But it was soon determined that it would be impossible to seal the leaking chlorine tanker until the propane fires from other tank cars had burnt themselves out. Firefighters, using some 4,000 meters of hose, had nearly a dozen major streams of water trained on the wreck site. Most were aimed at cooling the unexploded chemical tankers, while allowing a controlled burn of escaping gases.

An aerial view of the November 1979 Canadian Pacific derailment at Mississauga, Ontario, at the Mavis Road cross-street, showing the conflagration of various piled-up tanker cars on fire (white color) as numerous streams of firefighting water poured on the blazing tank cars.

More evacuations were ordered as winds changed. At about 5 a.m., the Solicitor General of the Ontario Cabinet was notified. As dawn broke, emergency officials and the town’s mayor met to consider their options. Again, the evacuation zone was expanded, including a decision to evacuate Mississauga General Hospital and two adjacent nursing homes. By early afternoon, the evacuation zone now extended beyond the Square One shopping center, the site of the first evacuation center. Evacuees there were transferred to other centers. A mass exodus of residents was now underway—some with packed luggage, others abandoning Sunday dinners about to be served.

During the evacuation of Mississauga, Ontario residents away from the chemical train wreck, auxiliary policeman Neil Porter, wearing gas mask, directs traffic at the intersection of highway routes 10 and 5. Toronto Star file photo.

At the day’s end, at least 218,000 residents had left their homes. Others put the number closer to 300,000. “The southern part of Mississauga, Canada’s ninth largest city with a population of 284,000, was a virtual ghost town,” reported one later account in, Derailment: The Mississauga Miracle. It remained the largest peacetime evacuation in North America until Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

By 10 a.m. Monday, November 12th, at least three propane cars were still burning. Officials feared that one might explode during rush hour, or that chlorine might waft over the area’s highways, trapping thousands of commuters in their cars. The Queen Elizabeth Way, the busiest stretch of highway in Canada, which runs through the central part of Mississauga, was closed at its eastern and western entrances to the town. Commuter traffic to Toronto was rerouted around the evacuated area, causing massive traffic jams.

The Queen Elizabeth Way, the busiest stretch of highway in Canada, which runs through the central part of Mississauga, was closed at its eastern and western entrances to the town. Commuter traffic to Toronto was rerouted around the evacuated area, causing massive traffic jams.

Back at the burning train wreck, a manufacturer of railway tank cars had prepared a steel patch to cover a one-meter hole in Dow’s chlorine tanker car. Some chlorine had already escaped, but officials assumed there was more remaining. Dow Chemical computers were enlisted to run scenarios of possible movements of leaking chlorine in the area to help emergency responders. “We have 90 tons of chlorine slowly leaking out,” explained police chief, Doug Burrows. “We have to know where it could go under different weather conditions. We have to know about every possible circumstance …” Railway crews, meanwhile, carefully removed box cars and tankers from the area which had not derailed, and attempted to clear debris at the accident site without disturbing the piled-up chlorine and propane tank cars.

At the November 1979 scene of the Mississauga train derailment, water streams continue to soak the still-burning rail cars as firefighters wearing breathing equipment head for work on the wreckage. Jack Dobson / The Globe and Mail

Staff of the Ontario Ministries of the Environment and Labor monitored the air and found a few pockets of chlorine gas in low-lying areas, but no significant hazard for the general area. Police patrolled deserted streets for looting and checked all vehicles entering the area. Public safety officials would not consider lifting the evacuation order and giving the all-clear signal until all the fires were out and the chlorine danger had ended.

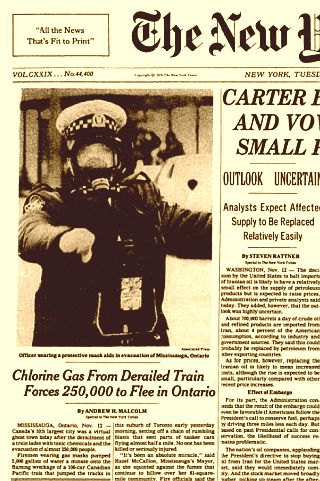

The November 13th, 1979 edition of the New York Times ran a front-page story on the Mississauga train wreck w/ headline, “Chlorine Gas From Derailed Train Forces 250,000 to Flee in Ontario.”

“…Firemen wearing gas masks pumped 5,000 gallons of water a minute onto the flaming wreckage of a 106-car Canadian Pacific train that jumped the tracks in this suburb of Toronto early yesterday morning, setting off a chain of rumbling blasts that sent parts of tanker cars flying almost half a mile…”

Back in Mississauga, November 13th was day four of the ordeal. One of the last big propane fires went out at about 2:30 a.m. and the focus moved to patching the chlorine tanker. By late morning that day, some evacuated hospital patients were being returned to their hospitals just outside the evacuated areas, but the city’s hospital remained closed. By late afternoon, the evacuation zone was reduced to a smaller area after air sampling indicated no hazard, allowing 144,000 residents to return home.

However, closer to the derailment, the evacuation order stayed in force, as there was still concern about chlorine. Workers had been hampered in completely sealing the leaking chlorine tanker, which was still blocked by another car. With an incomplete seal, some chlorine continued to escape. Other tankers, however, were being drained of their contents and hauled away, even as one propane tanker flared up again.

On day five, pockets of chlorine gas monitored in the evacuation zone still presented a health hazard.On day five, November 14th, workmen made a risky maneuver lifting and draining a half-empty propane tanker to get at the problem chlorine tanker, gambling that the propane tanker would not explode. Elsewhere on the site that day, a large white cloud of chlorine and water vapor rose from debris. Pockets of chlorine gas monitored in the evacuation zone still presented a health hazard for young children, the elderly, and those with respiratory problems – and also first responders. Eight firefighters walked into a pocket of chlorine gas that day near the wrecked tank cars and were admitted to the hospital.

Some years later, Barry King, a police inspector and command post co-ordinator at the time of the derailment, recalled an encounter he and one firefighter had with the leaking chlorine tanker: “I went down with one firefighter near the train, and this puff of chlorine gas waved over toward us. It just looked like a funny little cloud. He [ the firefighter] got a real dose of it and down he went. I don’t believe he ever went back to work. I had a tenth of what he had, but it was just enough to sear me. I was coughing up green phlegm the whole week. Doctors told me I would start feeling the effects of the chlorine when I got older. I started feeling it around 51. …Now I can only walk my dogs past three or four houses before I have to sit down.”

Back in 1979 at the derailment scene, frustration had grown among some evacuated residents, as a 25-square-kilometer area remained closed. Traffic was still barred at two entrances to the Queen Elizabeth Way.

On day six, November 15th, crews worked through the night and early morning, as 20- to-30 kilos of chlorine per hour continued to escape. The steel patch could not be fitted tightly over the rupture. A neoprene air bag was jerry-rigged over the opening which all but completely sealed the tanker, and officials announced there was little leakage. But that did not end the ordeal.

November 1979. A group of workers at the Mississauga, Ontario derailment site.

Between 7.5 and 10 tons of liquid chlorine still remained in the Dow Chemical tank car. Most of the tanker’s 90 tons of chlorine had been sucked up into the original fire ball at the wreck, with the resulting chlorine gas dispersed over Lake Ontario, according to officials.

Still remaining inside the tanker, however, was a slushy ice mixture of chlorine and water that had built up on its walls from the water poured on by the fire hoses. Scientists worried that this layer of ice might break up and fall into the liquid chlorine, exposing it to the air. This complication delayed the clean-up operation, as it was decided that pumping would not start until favorable winds prevailed. That occurred about 11 p.m. Still, the remaining 72,000 evacuated residents could not return to their homes that night since the chlorine had not been removed.

The Toronto Sun of November 19, 1979 reporting on the difficult week Mississauga had with the toxic derailment.

By 7:45 p.m. that evening – Friday, November 16th, 1979 – the city was reopened and police removed the remaining road blocks. Only the derailment site remained off-limits, as there was still wreckage to clean up and one remaining chlorine tank car to deal with. By late evening, the last evacuation center was closed and by midnight, police at the site finished their duties.

During the following week, the remaining chlorine tanker was finally emptied and the last pieces of emergency and fire equipment were removed from the scene. But officials continued to warn the public to avoid the derailment site because of dangerous chemicals that had soaked into the ground there. The clean-up of the wreckage at the site, and of contaminated soils there, would continue for another month or more.

In the aftermath of the accident, it was clear to many Canadians that Mississauga—and nearby Toronto—had dodged a major catastrophe.

The derailment occurred just after the train had passed through one of the most concentrated residential areas of Mississauga. The chemically-laden tank cars just happened to leave the tracks at one of the few places where a large area of undeveloped land existed—one of the few such places in all of greater Toronto.“We were lucky. . . . If the derailment had happened in metro Toronto just 20 miles up the tracks, we’d have had it. Thousands would have died.” And because of the propane explosions at the scene, much of the escaping chlorine was taken up into the fire and into the atmosphere rather than released as a toxic gas along the ground. There were also no fatalities.

Dr. Martin Dobkin, former emergency room physician at Mississauga Hospital, noted in a later interview, that the emergency staff at the time of the accident had been expecting the worst, given that chlorine was involved: “We were expecting dozens and dozens and dozens of mass casualties,” he explained, as he and other hospital staff were then preparing for emergency care following the derailment. But those casualties never came. However, some first responders and others dealing with the fires and wreckage would have delayed health problems some years later.

Toronto Star newspaper photo showing fireman Colin Cyr – after the fires were out and site clean-up began – examining gaping hole in the chlorine tanker that had forced the mass evacuation of Mississauga following the November 1979 derailment of Canadian Pacific freight train No. 54.

“We were lucky we escaped that one,” said Harold Morrison, reflecting on the disaster in in November 1984. Morrison was chairman of the Metro Toronto Residents Action Committee that formed shortly after the incident. “If the derailment had happened in metro Toronto just 20 miles up the tracks,” he explained, “we’d have had it. Thousands would have died.” Indeed, luck had played a key role. But the Mississauga accident had changed the political and industrial landscape in many ways – not least in terms of chemical hazards and public safety.

Chemical Dangers

Cover of “Report of the Mississauga Railway Accident Inquiry,” by Canadian Supreme Court Judge, Samuel Grange, heard from 169 witnesses over four months and issued a long list of recommendations. Dec 1980, 213 pp. Click for PDF.

Among the called-for changes were technical improvements, such as the use of roller bearing-equipped rail cars, and other more commonsense approaches, such as lowering train speed limits in populated areas. The disaster also sparked changes for tightening rules on transporting dangerous cargoes, setting a minimum number of crew members on such trains, and standardizing hot box detectors and roller bearings.

In the Canadian chemical industry, meanwhile, there were those who knew the Mississauga incident had touched a nerve about the movement of dangerous chemicals—chlorine in particular. Even as the incident unfolded, newspaper stories and editorials appeared with headlines such as “Railway Roulette,” “How Safe is The Freight,” and “The Road to Asphyxia.” People began asking questions about rail safety and chemical safety, and there were calls to ban the transport of hazardous chemicals—especially through highly populated areas.

According to Jean M. Belanger, who was president of the Canadian Chemical Producers Association in the early 1980s, the Mississauga train wreck and evacuation catalyzed the effort to advance a set of environmental and safety principles within the chemical industry, later known as “Responsible Care,” which later also took hold in the U.S. Earlier attempts to adopt a set of chemical industry safety principles in Canada had failed.

“In 1979, environmental awareness among companies was only starting,” explained Belanger. “Regulations were causing concerns to the degree they would limit flexibility of companies to do business. . . ” But then, a few accidents occurred. “For Canada it was the Mississauga train derailment. . . ,” said Belanger. “It put the spotlight on chemicals: Are they creating more problems than they are solving? That gave spirit to start the movement that became Responsible Care. . . . ” In the U.S., the Responsible Care process was catalyzed by the 1984 Union Carbide gas release disaster in Bhopal, India. But years after Responsible Care had become a well-established mantra of Canadian and U.S. chemical officials – and regarded as ineffective by critics – toxic spills and chemical releases, including those involving rail operations, would continue to occur.

This July 1980 U.S government report – “Major Railroad Accidents Involving Hazardous Materials Release” – lists some 75 such incidents that occurred in the 1969-1978 period. Click for PDF.

Long History

There is, in fact, a long history of rail accidents involving toxic and hazardous material in the U.S. and Canada. One 1980 U.S government report – “Major Railroad Accidents Involving Hazardous Materials Release” – lists some 75 such incidents that occurred in the 1969-1978 period.

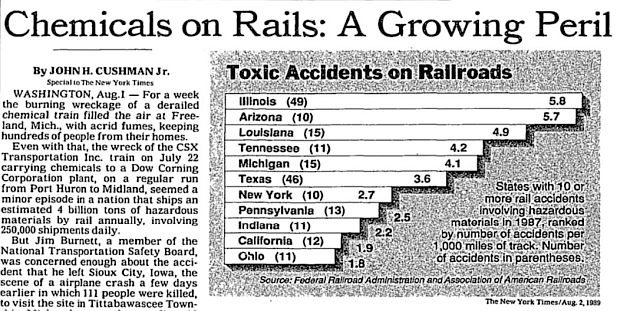

Derailments releasing hazardous materials continued through the 1980s, as one New York Times story of August 1989 appeared with the headline: “Chemicals on Rails: A Growing Peril.” That story listed dozens of such incidents across the U.S. (story w/graphic shown below).

Among the toxic chemical derailments noted, for example, was one that occurred on February 2, 1989 in Helena, Montana, and another on February 29, 1989 in Akron, Ohio. Both resulted in the evacuation of thousands of residents.

In the Montana case, a 49-car train operated by the Montana Rail Link became an “out-of-control runaway” that collided with a standing three-unit locomotive, derailing 28 cars, puncturing at least 2 of the derailed cars. One of those cars contained isopropyl alcohol and acetone and the other, hydrogen peroxide, which exploded minutes after the collision. According to the Times, “pieces of wreckage were hurled a quarter of a mile, and windows three miles away were shattered by the explosion. Fifteen people were injured, power in the area was temporarily lost, and 3,500 people had to be evacuated in temperatures of 27 degrees below zero.”

In the Ohio accident, a 21-car CSX train, including nine tank cars containing the highly flammable chemical butane, jumped the tracks, with 2 tankers breached, releasing butane and starting a fire that spread to an adjacent chemical plant owned by the B. F. Goodrich Company.

In Freeland, Michigan, on July 22, 1989, a CSX train carrying chemicals to a Dow Corning plant, on a regular run from Port Huron to Midland, derailed. Initially, at least 3,000 people were forced to evacuate from a 15-square-mile zone around the derailment. A chemical fire in a derailed tanker car burned into a fifth day. The “all clear” wouldn’t come until the chemical chlorosilene in the derailed tanker had burned off and two other derailed cars with toxic plastic ingredients were removed.

New York Times story of August 1989 included graphic – “Toxic Accidents on Railroads” -- listing for 1987, states with 10 or more rail accidents involving hazardous materials (number in parentheses), ranked by number of accidents per 1,000 miles of track.

Continuing through the 1990s and early 2000s, chlorine releases were among toxic releases that occurred with rail accidents in those years. On April 11, 1996, for example, a Montana Rail Link freight train derailed 2 miles west of Alberton, Montana, and released 64.8 tons of liquid chlorine. The chlorine quickly evaporated, forming a gas cloud that drifted toward the town of Alberton, forcing an evacuation. That story is covered in a Kindle book under the tile, Alberton Montana: Anatomy of a Toxic Train Wreck, and also as a two-part print edition titled, Gassed: The True Story of a Toxic Train Derailment. In 2005, more than 100,000 pounds of chlorine gas was released in South Carolina when 18 cars derailed. That crash killed nine people and exposed more than a thousand others, sending hundreds to hospitals with lung injuries.

|

OIL/CHEM TRAIN WRECKS July 6, 2013 / Lac-Megantic, Quebec December 30, 2013 / Cassleton, ND January 7, 2014 / Plaster Rock, N.B. February 13, 2014 / Vandergrift, PA February 16, 2015 / Mt. Carbon, WV March 5, 2015 / Galena, IL March 7, 2015 / Gogama, Ontario May 6, 2015 / Heimdal, ND June 3, 2016 / Mosier, OR April 2017, Money, MS June 22, 2018 / Doon, IA December 22, 2020, Custer, WA February 3, 2023 / E. Palestine, OH |

Among more recent U.S. and Canadian rail disasters involving oil, chemical, or other hazardous materials occurring during the 2013-2023 period, are those listed in the sidebar at right, here offered as samples and not a complete list.

Of these, the February 3rd, 2023 derailment of a Norfolk Southern freight train carrying hazardous materials in East Palestine, Ohio near the western border of Pennsylvania, has garnered much public and media attention. Some 51 cars derailed there, 49 of which ended up in a derailment pile, which then caught fire and burned for several days. Of the 51 derailed cars, 11 of them were tank cars which dumped 100,000 gallons of hazardous materials, including vinyl chloride, benzene residue, and butyl acrylate. A controlled burn and evacuations of nearly 3,000 local residents followed.

This derailment, however, became something of a major political and media event, with an ongoing NTSB investigation, state and federal environmental involvement, and proposed legislation in the U.S. Congress to address rail safety shortcomings. It is likely to remain a continuing story for some time to come, raising the focus on rail safety and the movement of toxic and hazardous materials through towns and cities.

Chem Cargoes

The U.S. has about 140,000 miles of rail lines used for freight cars, which are owned and maintained by private organizations. Each year, nearly a billion tons of hazardous materials are shipped by rail, according to the American Chemistry Council.

Hazardous materials, or “hazmat,” are defined by the federal government as “substances or chemicals that pose a health hazard, a physical hazard, or harm to the environment,” such as unrefined oil, liquid natural gas and industrial manufacturing chemicals. In 2021 freight trains moved more than 2 million carloads of all chemicals, the vast majority of which occurred without incident. However, when it comes to toxic and hazardous substances even a few derailments in the right places can present serious dangers to public health and safety.

According to 2023 reporting by CNN, the Federal Rail Administration provided data that showed 149 rail incidents occurred in the last decade involving the release of hazardous materials from moving trains. This data, it was noted, is self-reported by the train companies.

Other 2023 reporting by USA Today, analyzing 10 years of federal rail incident reports, found over 5,000 incidents of hazardous materials spilling or leaking from trains that were either in transit or sitting in rail yards. In 2022, according to USA Today, rail companies reported 337 spills or leaks of hazardous materials – 32 of which were classified as “serious.” And while trucks transporting chemicals on the nation’s highways have numerically more accidents than do railroads, the volume carried by rail makes them potentially more serious when they do occur.

Still other 2023 reporting at TheHill.com, has noted that the kind of cargo railroads may be carrying more of in the near future could mean increased rail traffic and possibly more serious rail accidents ahead – especially given possible growth in certain sectors, such as: fracked oil (the 2010s’ oil boom saw more oil train accidents) and fracked methane used in making plastics and also for LNG – liquified natural gas – an expanding export market; as well as more vinyl chloride also for expanding U.S. and global plastics production; and finally, more bio-fuels production and transport of ethanol and bio-diesel.

Railroad Power

In the U.S., meanwhile, railroad companies have historically been among the nation’s most powerful corporations, some reaping huge wealth and economic advantage from historic government land grants and mineral rights during their 19th century build-out in the west. True, the rail companies remain an important and essential force in moving goods and raw materials that keep America’s economy humming – all to the good. Still, rail power – like so much corporate power in America – has become concentrated in a handful of companies, as the graphic below illustrates. And such power typically results in further economic advantage and political leverage.

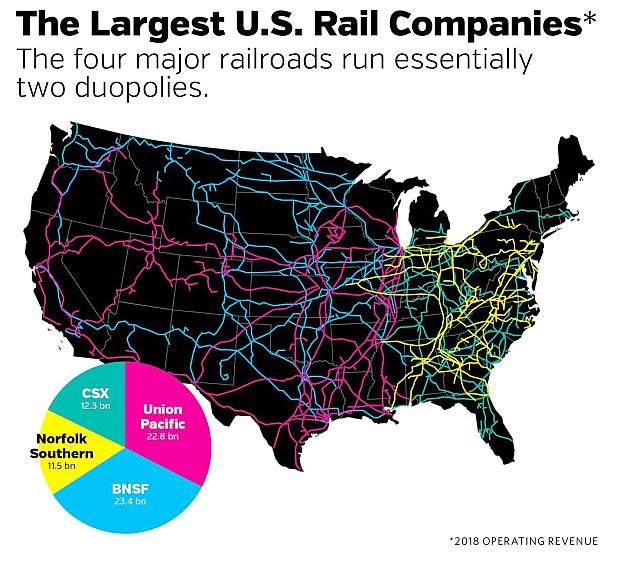

Map showing rail company service area by color, with pie chart showing 2018 operating revenue ($ billions) for the each rail company: BNSF ($23.4 bn); Union Pacific ($22.8); CSX ($12.3 bn), and Norfolk Southern ($11.5 bn). American Prospect / Feb 2022.

At the very least, given the continuing litany of rail accidents in the U.S. over the last 50 years or more, tougher oversight and regulation are needed, aimed principally at improved safety performance and environmental protection. Railroad labor unions have recommended obvious safety measures such as increasing the number of crew members on each train, limiting train length, improvements to safety monitoring systems, increasing time and staff for railcar inspections, and modernizing braking systems. Beyond these, perhaps “citizen suit” provisions should also be added to the regulatory mix, affording a measure of community control and citizen watch-dogging over the railroads that run through numerous American towns and cities. And for very bad actors – those causing repeated harms to society – revoking the corporate charter to do business should also be an option.

For additional stories at this website on oil and chemical disasters see the “Environmental History” topics page, and generally the Home Page for other stories. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing and continued publication of this website. Thank you – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 9 March 2023

Last Update: 10 March 2023

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/PopHistoryDig

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Toxic Train Wreck: Mississauga, 1979”

PopHistoryDig.com, March 9, 2023.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Mississauga Library System, Local Archives: “Mississauga Train Derailment – November 10th 1979,” Mississauga. Ontario, Canada.

“Derailment: The Mississauga Miracle,” Mississauga News, Special Edition, November 12, 1979.

“Tanker Disaster: The Miracle Is, No One Was Hurt,” Toronto Star, November 12, 1979.

“Deserted City Crippled,” Mississauga News, Special Edition, November 12, 1979.

Insert, Toronto Sun, November 12, 1979.

“Chlorine Fear After Train Derailment Clears Mississauga…,” Globe and Mail, November 12, 1979.

The Spectator, November 12, 1979.

“Chlorine Leak Plugged, Blaze Dying,” Globe and Mail, November 13, 1979.

Toronto Star, November 13, 1979.

Andrew H. Malcolm, “Chlorine Gas From Derailed Train Forces 250,000 to Flee in Ontario; New Evacuations Considered,” New York Times, November 13, 1979, p. 1.

“Welcome Home,” Mississauga Times, Special Edition, November 14, 1979.

“It’s Over,” Journal Record (Oakville), No-vember 14, 1979.

Mississauga News, November 14, 1979.

Andrew H. Malcolm, “Canadians Are Returning to City Hit by Rail Accident; Calls for Stricter Regulation,” New York Times, November 14, 1979, p. A-3.

“The Week They Closed Mississauga,” Sunday Star (Toronto), Special Section, November 18, 1979.

“Mississauga’s Lost Week,” Sunday Sun (Toronto), November 18,1979.

“Aftermath,” Mississauga Times, November 21, 1979.

“City In Crisis: Day by Day,” Mississauga News, November 21, 1979.

“Mississauga Nightmare,” Maclean’s, Novem-ber 26, 1979.

“Terror in Mississauga” (the month in pictures), Photo Life, April 1980.

M. J. Goldstein, “Mississauga Evacuated,” March 1980.

Julius Lukasiewicz, “The National Night-mare,” (undated, unnamed source).

“The Mississauga Disaster,” Reader’s Digest, March 1980, pp. 72-79.

“Mississauga; One Year After,” Sunday Sun, November 9, 1980.

Diana M. Liverman and John P. Wilson, “The Mississauga Train Derailment and Evacu-ation,” Canadian Geographer, 10-16 Novem-ber 1979, vol.XXV, no.4, 1981.

The Mississauga Evacuation. Final Report to The Ontario Ministry of the Solicitor General, The Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Toronto, November 1981.

“Miracle of… Mississauga,” Toronto Sun publication.

The Honourable Mr. Justice Samuel G. M. Grange, Supreme Court of Ontario, Commis-sioner, Report of the Mississauga Railway Accident Inquiry, December 1980, 213 pp.

UPI Archives, “Chemical Train Derails Near Saginaw, 17 Overcome by Fumes,” UPI.com, July 22, 1989.

Associated Press, “Train Fire Keeps Hundreds from Homes,” New York Times, July 25, 1989, p. A-10.

Associated Press (Freeland, MI), “One Thousand Evacuees Remain as Chemical Tanker Still Burns,” APnews.com, July 26, 1989.

Bob Mitchell, “Mississauga Remembers the Derailment,” Toronto Star, November 9, 1998.

“Remembering The Big One,” Mississauga News, November 15, 1998.

Bob Mitchell, “The Miracle of Mississauga,” Toronto Star, November 6, 1999.

Declan Finucane, “A Night of Memories for First on The Scene,” Mississauga News, November 10, 1999.

John Stewart, “Twenty Years Ago Today Derailment Rocked The City,” Mississauga News, November 10, 1999.

Toronto Sun, et.al., Miracle of Mississauga, Picture book & narrative on the Mississauga Train Derailment of November 1979 , 51 photos, Toronto, Canada.

Jack Doyle, “The Mess at Mississauga,” in Chapter 10, “Poisoning Canada,” Trespass Against Us: Dow Chemical & The Toxic Century, Common Courage Press, 2004, pp. 204-211.

“Mississauga Train Derailment: 30th Anni-versary,” HeritageMississauga.com, 2009.

Julie Slack, “Derailment Changed Our History,” Mississauga News, November 10, 2009.

Natasha Vicens, “More than 40 Percent of Pittsburgh Residents in Danger Zone for Crude Oil Train Derailment,” PublicSource .org, August 5, 2014.

“Crude Oil Transportation: A Timeline of Failure,” RiverKeeper.org (includes rail accidents in North America in 2013 and 2014).

Carola Vyhnak, “1979 Train Derailment Became Known as the Mississauga Miracle; Exploding Propane Tankers and Cars Loaded with More Hazardous Material Sparked the Evacuation of the Canada’s 9th Largest City, Which Would Become a Model for Crisis Management,” Toronto Star, November 16, 2017; updated March 27, 2018.

Timothy Cama, “Trump Officials Roll Back Obama Oil Train Safety Rule,” TheHill.com, September 24, 2018.

Larry Wood, Associated Press, “Graniteville [South Caroline] Continues to Recover Almost 15 Years after Train Crash, Chlorine Leak,” APnews.com, March 9, 2019.

Ben Cohen, “On the 40th Anniversary of the Mississauga Miracle, We Talk to Those Who Fought, Fled and Reported on the Fiery Derailment,” TheGlobeandMail.com, Novem-ber 8, 2019.

Trillium Health Partners, “Mississauga Miracle: 40 Years Later,” YouTube.com, 3:53 minutes, November 10, 2019.

Sahar Fatima, “How Planning and Bravery Amid Massive Explosions Led to the ‘Mississauga Miracle’ Forty Years Ago. A Mississauga Train Derailed, Causing a Massive Crash and Several Explosions, and Released Clouds of Deadly Chemicals,” Toronto Star, Sunday, November 10, 2019, updated March 3, 2020.

Zane Gustafson & Eric de Place, “A Timeline of Oil Train Derailments In Pictures. Since 2013, North America Has Seen at Least 21 Oil Train Accidents—And Counting,” Sightline.org, February 26, 2021.

Jon Hurdle, “Towns Join Push to Block ‘Bomb Trains’; Activists Want Permit Pulled That Allows Trains to Transport Liquefied Natural Gas to Gibbstown,” NJspotlightNews.org, November 23, 2021.

Jayme Fraser, Tami Abdollah, “How Often Do Train Wrecks Spill Hazardous Chemicals into Neighborhoods? Here’s What Data Shows,” USAToday.com, February 9, 2023.

Ella Nilsen, “6 Key Things to Know after the Toxic Train Derailment in Ohio,” CNN.com, February 15, 2023.

David Sirota, Rebecca Burns, Julia Rock and Matthew Cunningham-Cook, “Opinion: Over 1,000 Trains Derail Every Year in America. Let’s Bring That Number Down,” NewYork Times.com, February 17, 2023.

Saul Elbein, “Four Rail-Borne Risks Moving Through American Communities,” TheHill .com, February 18, 2023.

_________________________________________