Note: Since this story was originally posted in September 2012, some Advance Publications properties, such as Parade magazine and The Times-Picayune/NOLA.com, have been sold to new owners. – j.d., 6/12/20

|

|

|

|

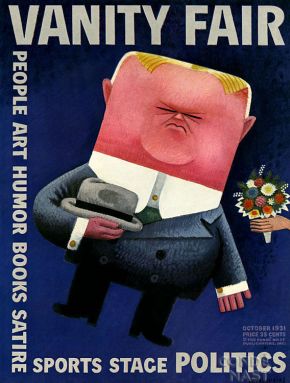

If you read Wired magazine, The New Yorker, or Vanity Fair, you’re reading material produced by a company named Advance Publications. And if you read Parade, the largest circulation Sunday supplement magazine in the U.S., or Golf Digest, or Glamour, these magazines are also published by Advance – as are Vogue, The Sporting News, Architectural Digest, and several others. In addition, Advance owns newspapers found in more than twenty-five American cities, including: Newark, NJ; Cleveland, OH; Portland, OR; New Orleans, LA; and Syracuse, NY. Another 40 weekly titles are published by Advance through its American City Business Journals. Cable television outlets owned by Advance serve 2.4 million customers in Florida, California, Michigan, Indiana and Alabama. On the web, Advance Internet operates more than 100 websites, most of which serve and extend the company’s print and cable operations. Reddit.com, the popular user-generated “social news” website, is one of Advance Internet’s properties.

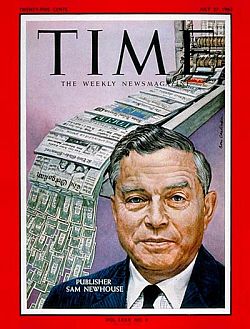

Advance Publications was formed and is owned by the Newhouse family of Long Island, New York. In recent years the Newhouse /Advance empire has ranked among the 50 largest private companies in the U.S. The company dates to the early 1920s, and grew to fame in the heyday of the newspaper business when its founder, Samuel I. Newhouse – “Sam” – steadily went about acquiring all manner of America newspapers during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Today, as of September 2012, Advance Publications is run at the corporate level by Sam’s two sons — S.I. Newhouse, Jr. (84), known as “Si,” and brother Donald Newhouse (81). Assorted other Newhouse family members assist in the management of various divisions and subsidiaries. Si and Donald will soon turn over control of the company to the next generation of Newhouse executives.

Yet, some say the Newhouse empire is “yesterday’s media company,” and will succumb to the albatross and high-cost of print in a digital age. Others believe the Newhouse empire will not only survive, but will thrive, continuing to be a dominant cultural force and contemporary story teller, setting trends in fashion, literature, and style as it goes. Whatever the outcome, there is 90 years of rich history here – a publishing and cultural time capsule of sorts, reflecting changes in publishing and media generally over that period. What follows is a narrative and visual look at some of that Newhouse history, and by extension, media and publishing history as well. First, Sam Newhouse, the founding father, circa 1920s.

Life magazine photo of Sam Newhouse, 1963.

Having left school at about the age of 13 due to his family’s poverty, Samuel I. Newhouse landed a job with a local judge in Bayonne, New Jersey. There, he was given the task of minding a local newspaper named the Bayonne Times which his employer had acquired in payment for a bad debt. Newhouse succeeded in making the paper profitable, and along the way, attended evening classes at the New Jersey Law School at Newark, receiving a degree in 1916. Newhouse was 21 by this time, and his boss, Judge Lazarus, paid him $30,000 a year, and gave him a 25 percent share the Bayonne Times. In 1922, with Judge Lazarus, Newhouse purchased the Staten Island Advance, one of the first newspapers he acquired – the property from which “Advance Publications” got its name. When Judge Lazarus died in 1924, Newhouse acquired the rest of the Staten Island Advance. He then focused on the idea of expanding newsstands in the region as a way to grow his newspaper – newsstands at the St. George Ferry Terminal on Staten Island and others throughout Manhattan, at LaGuardia and Newark airports, and at the Port Authority Bus Terminal in New York city, which became the world’s largest and most lucrative newsstand. Then came other newspaper acquisitions: the Long Island Press in 1932; the Newark Star Ledger in 1933, the long Island Star Journal in 1938; the Syracuse Journal in 1939; the Syracuse Herald-Standard in 1941; the Jersey Journal in 1945; and the Harrisburg Patriot of Pennsylvania in 1948.

Dec 1955: Newhouse makes Alabama deal.

In buying up newspapers, Newhouse adopted a low-key, non-threatening approach with the companies acquired. He usually kept the existing management and editors and was reluctant to upset the status quo, believing the papers should remain local institutions run by people in those communities.

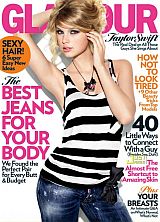

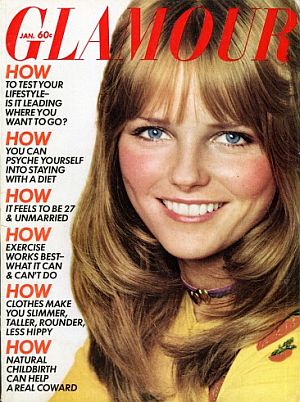

March 1958: “Glamour” shortly before the Newhouse acquisition.

The wealth of the Newhouse family at this point approached $200 million. Some began wondering exactly how Newhouse was generating the funds for his deals. A few even speculated that he was laundering money, using his newspapers as a front for a local mob organization’s illegal booze operations during prohibition. But it wasn’t that at all. Newhouse had just hired smart attorneys and accountants who figured out ways to pay the absolute least amount of corporate taxes while costing every expense they could and depreciating assets to the limit. They also structured each newspaper as its own operation, each attributed its own separate profits, avoiding a much higher commulative total under one, single-owned Newhouse entity. There was also a Newhouse Foundation created early on as an additional tax dodge, which some believe was also used to help finance the $18 million deal for the Alabama newspapers in 1955.

The 1960s

1962: Newhouse buys Louisiana newspapers.

Back on the newspaper acquisition trail, Newhouse acquired the Oregon Journal in 1961 for $8 million. By then he owned 16 newspapers. But in 1962, having failed to buy the Houston Post after he had made a generous offer to that paper’s owner — Ms. Hobby, who refused to sell — Newhouse was still itching to buy a paper, any paper. So he telephoned a newspaper broker named Allen Kander in Washington, D.C. Newhouse, then continuing his travels in the South, asked Kander where he might buy a newspaper in the region. Try New Orleans, Kander suggested. Newhouse did. Two weeks later, he set another record, paying $42 million for both of New Orleans’ newspapers: the morning Times-Picayune and its evening companion, the States-Item. The larger of these two, the Times Picayune, then had a daily circulation in excess of 195,000, with more than 300,000 sold on Sundays. The States-Item was an evening paper with a circulation of about 163,000.

S.I. “Sam” Newhouse on the cover of Time magazine, July 27th, 1962.

In the fall that year, Newhouse set out again to bag another newspaper. On October 12, 1962, The Wall Street Journal reported that Newhouse was planing to buy The World-Herald newspaper in Omaha, Nebraska. And a few weeks later Newhouse made a $40 million bid for the paper, which appeared to be accepted.

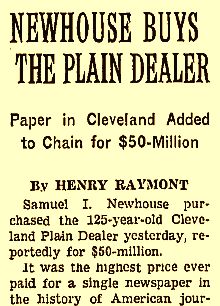

1967: Sam Newhouse acquired ‘The Cleveland Plain Dealer’ newspaper.

In 1966, Newhouse acquired three newspapers in Springfield, Massachusetts – The Springfield Morning News, The Republican, and The Morning Union – followed by three more in the south; The Mobile Register, The Mobile Press and The Mississippi Press-Register. The following year he set another industry record when he paid $54.2 million for the Cleveland Plain-Dealer.

As he went about his business, Newhouse gained a reputation as a tight-fisted owner and manager known for cost cutting. He also resisted unions and did not pay high salaries to his reporters. Nor did he impose any particular ideology or editorial line on his managers and editors, and for the most past, he maintained political neutrality. Said he in 1968: “My papers have different philosophies, and they’re about as wide apart as they can get. Some are Democratic, some are Republican. I am not going to try to shape their thought.” Many others in the business followed his “hands off” example.

The 1970s

By the mid-1970s, Sam Newhouse, then 80 years old, was still looking for more newspaper properties. In February 1975 he had acquired 25 percent of the stock in the Booth Newspaper group, a chain of eight small newspapers all within 200 miles of Detroit, Michigan. Booth also owned Parade magazine, a popular Sunday supplement. Local newspapers with monopoly positions like those in the Booth chain, were described by one 1975 analyst as offering “practically a licence to print money.” The eight papers – The Grand Rapids Press, The Flint Journal, The Kalamazoo Gazette, The Saginaw News, The Muskegon Chronicle, The Bay City Times, The Ann Arbor News and The Jackson Citizen Press – then had a combined circulation of about 506,000. But Newhouse wasn’t the only party interested in this newspaper group. The Times Mirror Company – then owner of the Los Angeles Times, Newsday, The Dallas Times Herald, and The Orange Coast Daily Pilot – was also interested. In the fall of 1976, Times Mirror made an offer to buy the Booth chain at $40 a share, which was more than double Booth’s stock price at the time. But Newhouse made a counter offer of $47 a share, which the Booth group accepted. In the end, Newhouse gained total ownership of the eight Booth newspapers and Parade magazine for $305 million.

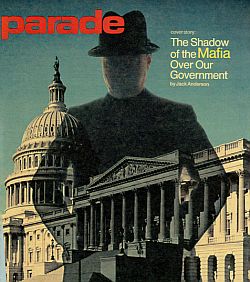

The look of Parade magazine in August 1977, not long after being acquired by Newhouse.

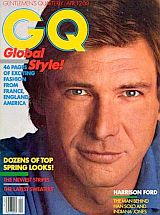

But in addition to the eight local newspapers, there was also something else. No small part of the deal was Parade magazine. Parade, in fact, gave Newhouse a window into many other newspapers, as it was then one of the leading Sunday supplement inserts – used by some 111 newspapers with a combined circulation of more than 19 million. And under the Newhouse umbrella, Parade would only grow in the years ahead. Elsewhere in the magazine business, in February 1979, Newhouse also purchased Gentlemen’s Quarterly from Esquire and rolled it into the Condé Nast magazine group, later renaming it GQ.

1974: Sam Newhouse.

By1979, the Newhouse operation held 31 daily newspapers with a total readership of more than 3 million, then the third largest U.S. newspaper chain behind Gannett and Knight-Ridder. With Sam’s passing, his two sons began running the company – S.I., Jr., known as “Si,” would head up the company’s magazine operations, and Donald Newhouse would run the newspapers.

The banners of the two main newspapers in New Orleans ran together for a time after Newhouse consolidated the them. But in 1986, The States-Item name was dropped.

The 1980s

In the 1980s, although no newspapers were acquired, some were consolidated, especially in cities where Newhouse owned both the morning and afternoon papers. In New Orleans, The Times-Picayune was combined with The States-Item. Newhouse had bought both papers in 1962. On June 2, 1980, The States-Item was gone but the surviving paper shared a joint banner using both names. Six years later, The States-Item name was dropped altogether, and the newspaper of New Orleans became The Times-Picayune.

In Portland, Oregon, The Oregon Journal was merged with the Oregonian in 1982. That same year, the Cleveland Press ceased operation. The Newhouse-owned Cleveland Plain-Dealer then became the city’s only daily newspaper. Allegations were made that Newhouse management had paid The Press’ owner to go out of business, and in 1985, a grand jury began an anti-trust investigation into the Newhouse role, but charges were never filed. In other newspaper business, Newhouse also sold the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in 1984.

The Random House logo.

In 1980 Newhouse also sold five television stations to the Times Mirror Company for $82 million. He sold the stations primarily because his company then held newspapers in those same cities and he feared the government would eventually order the sale on anti-trust grounds. Newhouse used part of the money from that sale to buy up other cable TV systems, and by 1981 or so had over 500,000 cable television subscribers. Forbes magazine around this time observed: “By the most conservative standards, the Newhouse properties are worth well over $1 billion. They are unencumbered by a penny of debt and except for a 49% interest in a paper mill, are 100% owned by the Newhouse family or by trusts they control.”

|

|

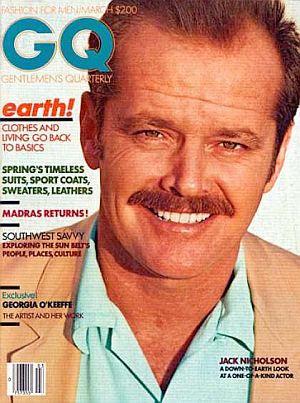

In the magazine business, meanwhile, the early 1980s at Newhouse were a time of revamping and relaunching some of the company’s acquired properties. Among these was Gentleman’s Quarterly, or GQ, a men’s fashion magazine dating to 1931. At the time Newhouse acquired it, GQ had become known as a gay men’s magazine. But at the Newhouse Condé Nast shop during the early 1980s, the decision was made to give GQ a more masculine focus, as the company wanted to reach a broader market and become a competitor to Esquire. The covers in the early 1980s began featuring male movie stars and athletes, among them, actors such as Jack Nicholson, Mel Gibson, and Harrison Ford and athletes such as Washington Redskins quarterback, Joe Theismann. Advertising pages in the magazine featured male models with admiring females.

|

|

|

|

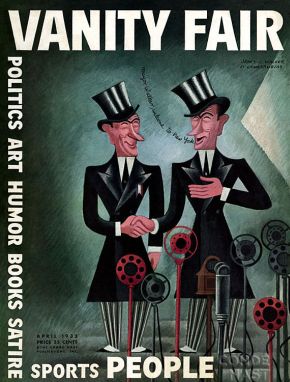

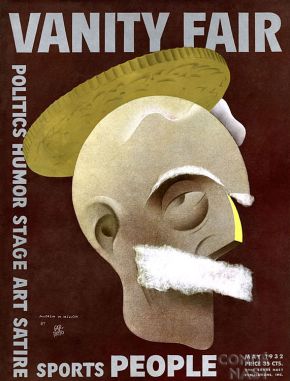

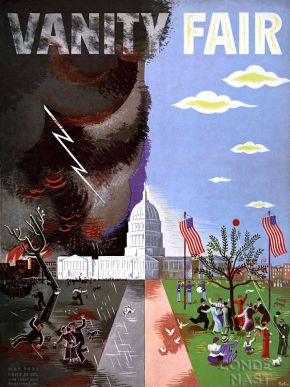

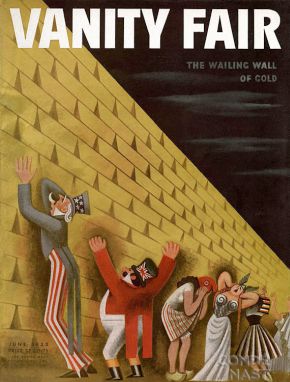

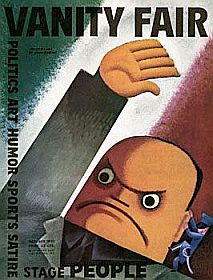

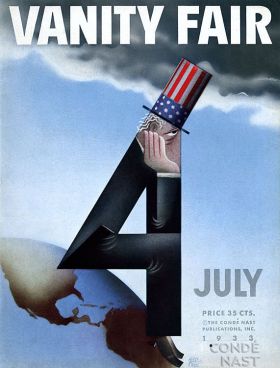

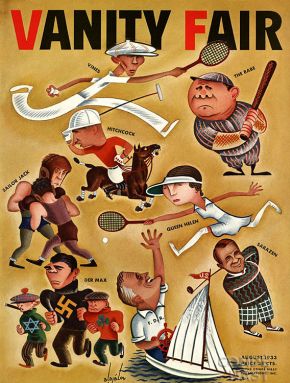

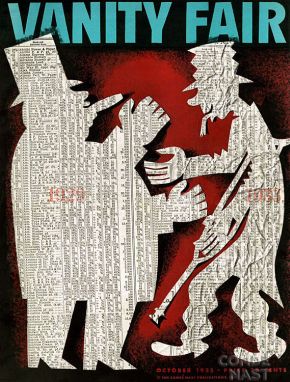

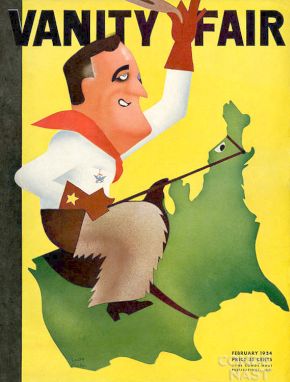

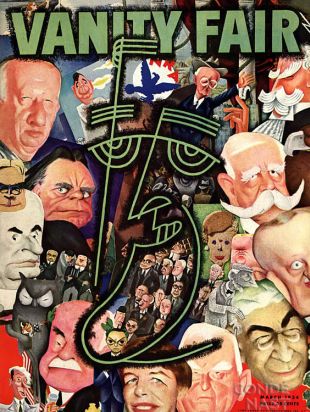

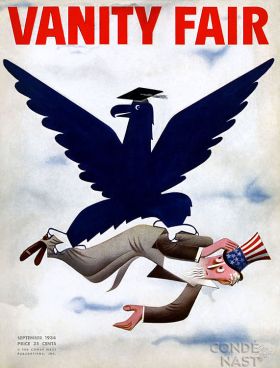

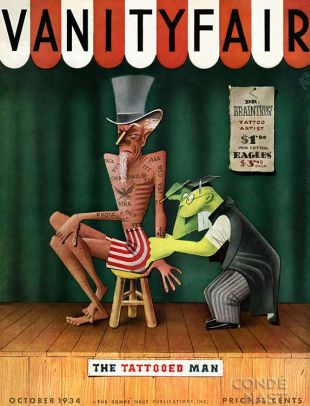

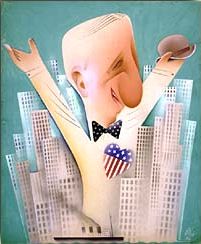

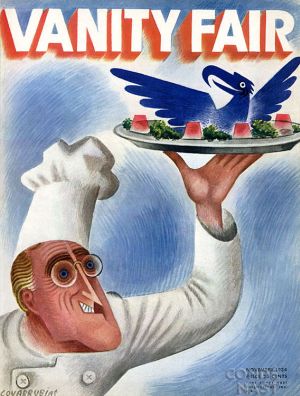

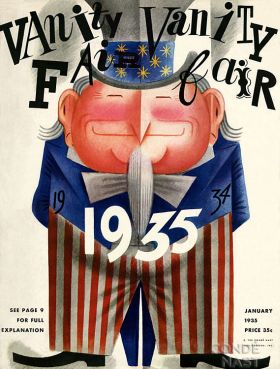

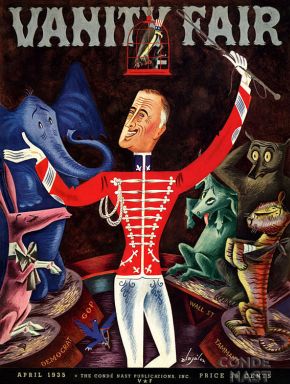

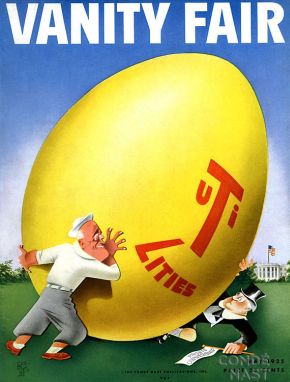

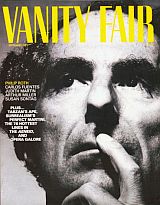

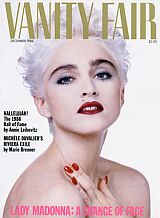

In early 1983, Newhouse also made a major move with the re-launch of Vanity Fair as a glossy celebrity magazine focused on literature, the arts, politics and popular culture. Some $10 million was invested in strengthening the magazine editorially. It was also redesinged to give it a new look and a new start, hoping to restore it as the central publication within the Condé Nast group. The first new issue included some 290 pages with a short novel by Gabriel Garcia Márquez, winner of the 1982 Nobel Prize for literature, and also articles by writer Gore Vidal and paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould. Photographer Irving Penn, described as “one of the greatest portrait photographers of the 20th century”, was enlisted in the Vanity Fair re-launch during 1983. Penn, who began shooting for Vogue magazine in 1943, did six successive covers for Vanity Fair in 1983, August through December 1983. Four of those cover shots, which featured celebrity authors and actors, are shown here at right – from top left: novelist Philip Roth, September 1983; writer and playwright Susan Sontag, October 1983; European writer, Francine du Plessix Gray, November 1983; and comedian-in-disguise, Woody Allen, December 1983. A round of reviews followed the Vanity Fair makeover, including some that were sharply negative, as those that came from Time and The New Republic. ”We never believed we were producing a perfect magazine when we relaunched Vanity Fair,” said Si Newhouse at the time. He acknowledged there was much work ahead — “before we get the wonderful, seamless quality a mature magazine has.”

One step to getting Vanity Fair on the right track, Newhouse hoped, was the January 1984 hiring of Tina Brown, the former editor of The Tatler, society magazine in London. Brown, an Oxford University graduate, had given The Tatler a more modern and satirical edge, and it appeared that’s what Newhouse had in mind for Vanity Fair as well. Time would tell.

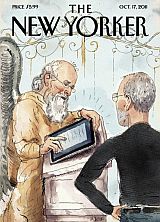

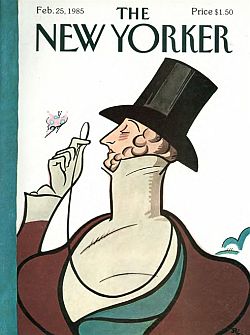

The New Yorker, Feb 25, 1985, featuring famous mascot, Eustace Tilley, about the time S. I. Newhouse acquired it.

The acquisition of The New Yorker stunned the publishing world. At the time, many worried for the fate of the magazine’s vaunted literary quality, which showcased some of the finest writers in America, might suffer under the Newhouse cost-conscious management style. An unsigned article published in the magazine during the management change questioned whether the new ownership would result in erosion of The New Yorker’s long tradition of editorial independence. Fears escalated when the long standing editor of some 32 years, William Shawn, was fired by Newhouse. Depsite the concerns, things at The New Yorker continued pretty much as they had, as the magazine’s integrity and quality were not compromised.

In the business world, however, there were those who believed that buying up The New Yorker made no economic sense, as the magazine was seen as “old media” and on the way out – especially as television’s “quick take” and “sound bite” stylistic tendencies began encroaching on the print world. But Si Newhouse was a careful student of the magazine business. In September 1988 he told Geraldine Fabrikant of the New York Times that The New Yorker was then “one of the greatest things in journalism and the most interesting thing I am involved in.” He added: ”People have been convinced that no one is reading any more, so that bringing The New Yorker back is a fascinating challenge,” he said. ”When I study the health of magazines, I study renewal rates,” he explained. ”That tells you whether a magazine is right for its readers. Once you have a good reader base, advertisers invariably follow.” The New Yorker at the time had a renewal rate of 72 percent, which was then 2 points above the industry average.

|

|

|

|

Vanity Fair, meanwhile, under Tina Brown, faced a make-or-break situation, with 1984 circulation of 200,000 and very little advertising. Rumors circulated that Si Newhouse might decide to take the barely-surviving magazine and fold it into The New Yorker. But under Brown’s direction, Vanity Fair began to show itself in a new way, offering a range of new cover subjects, stories and photography.

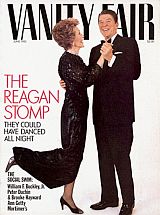

Three Vanity Fair cover stories during 1985 are sometimes credited as the turning point. First was the Vanity Fair cover of Ronald and Nancy Reagan dancing in the White House by photographer Harry Benson for the June 1985 issue. Then came the August 1985 cover story of accused murderer Claus von Bulow with his mistress Andrea Reynolds on the cover and in other photos by Helmut Newton of von Bülow and Reynolds in matching leather jackets that made them look, as Reynolds put it, like “S&M people.” And finally, there was Tina Brown’s own cover story on Princess Diana of October 1985 titled “The Mouse that Roared,” which examined how marriage and a public life had changed young Diana, a former preschool teacher. Princess Di was photographed in full House of Windsor regalia for the issue. But perhaps more notably, the Princess Diana story also broke news of the royal couple’s fractured marriage. The issue boosted Vanity Fair newsstand sales by 100,000 copies.

Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown with Si Newhouse, 1990.

2010 edition of “Condé Nast Traveler,” launched in 1987. |

“Details” magazine in 1992 after a Newhouse overhaul. |

Si Newhouse, meanwhile was also adding other magazines during the late 1980s. Among these was a magazine that would later become the Condé Nast Traveler, a monthly magazine for affluent readers and travelers that was acquired from American Express as Signature magazine, but was vastly upgraded and relaunched by Newhouse in the fall of 1987 with an infusion of about $40 million. In early 1988, Details magazine was acquired, which was originally a somewhat quirky chronicle of Manhattan’s downtown art and club scene when Newhouse acquired it for $2 million, but was transformed into a young men’s fashion and lifestyle magazine. Later the same year, Woman magazine was acquired, an eight-year-old magazine with a circulation of 525,000. Somewhat less sophisticated than others in the Newhouse / Condé Nast group, Woman would target a newer market segment. Meanwhile, an older but reliable magazine on the newspaper side, Parade, was enjoying a growing readership base. By 1989 the Sunday supplement was included in some 330 newspapers with a circulation of more than 35 million readers. A full-page color ad in Parade at this time would cost its sponsor about $420,000.

Elsewhere in the late-1980s Newhouse empire, Random House in 1988 added Crown Publishing to its growing group of imprints. The IRS about this time filed charges against the Newhouse family, claiming taxes due on the estate of Sam Newhouse. The family had filed an estimated amount of $48 million. The IRS, however, said the amount due was more in the neighborhood of $600 million, plus $300 million more in penalties. However, the courts later found in favor of the Newhouse family. By 1989, Forbes magazine, in its annual listing of the richest Americans, found the Newhouse empire to be worth some $5.2 billion. Fortune magazine estimated Newhouse wealth a bit higher, at $7.7 billion. In any case, by the close of the decade, Newhouse was the nation’s the No. 1 publisher of general books, the third largest magazine publisher, the fourth largest newspaper chain, and one of the top 15 cable TV providers.

The 1990s

|

|

|

|

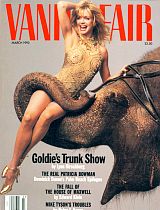

Vanity Fair continued to be a pop culture trend-setter in the early 1990s, featuring cutting-edge stories, Hollywood celebrities, and sometimes controversial covers, not the least of which was a nude and very pregnant Demi Moore on the cover of the August 1991 issue. “More Demi Moore,” read the cover tag line, with the featured subject photographed by Annie Leibovitz, as Moore was then seven months pregnant with her daughter. The cover was intended to be “anti- Hollywood” and “anti-glitz,” according to some accounts, and it succeeded in sparking intense controversy and debate, receiving wide media coverage in the process. Other Vanity Fair covers through 1992 featured Hollywood celebrities, rock stars, and enticing cover stories, among them: Jessica Lange in October 1991, Goldie Hawn in March 1992, and Mick Jagger in April 1992.

Vanity Fair’s circulation had jumped to 1.2 million by 1991. Advertising pages were also up in 1991, to about 1,440 pages. Revenues from circulation rose, especially from profitable single-copy sales at $20 million. Vanity Fair was then selling some 55 percent of its copies on the newsstand, well above the industry average of 42 percent. Tina Brown had done so well at Vanity Fair that Si Newhouse decided in July 1992 to make her editor of The New Yorker, hoping to give that magazine a bit of Vanity Fair’s sharper edge. Graydon Carter was hired by Newhouse to replace Brown at Vanity Fair, which continued with engaging cover art, such as the August 1993 issue with Cindy Crawford and k. d. Lang, photographed by Herb Ritts. Vanity Fair stories had cultural and current affairs impact, too. In 1996, journalist Marie Brenner wrote a Vanity Fair exposé on the tobacco industry entitled “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” an article later adapted for the 1999 film, The Insider, with Al Pacino and Russell Crowe.

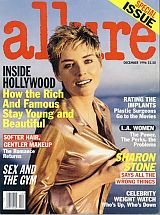

1996: “Allure,” Sharon Stone. |

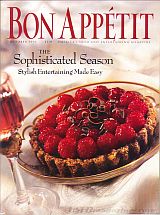

October 1995: “Bon Appétit.” |

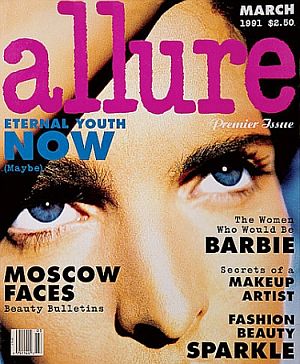

Beyond Vanity Fair and The New Yorker, the Newhouse enterprise continued to extend its reach in the magazine business. In 1991, it added Allure and others through the 1993 acquisition of Knapp Publications including, Architectural Digest and Bon Appétit. The following year, Newhouse acquired a 25 percent share of Wired, a San Francisco based monthly magazine focusing on new technology and how it affects culture, the economy, and politics. Newhouse had also offered some $500 million in backing to QVC, then in a 1993 bid for Paramount film studios, which QVC later lost to Viacom. On the newspaper side, the American City Business Journals were acquired by Newhouse in 1995 for about $270 million, adding business newspapers in some 40 cities with names such as the Atlanta Business Chronicle, the Cincinnati Business Courier, the Denver Business Journal, and others. Still, newspapers continued to be the cash cow for Newhouse, generating the largest revenue stream for the company through the mid-1990s, usually north of $1.5 billion annually. In cable TV, meanwhile, Newhouse and Time-Warner Cable combined cable systems in a joint venture. That deal brought Newhouse Broadcasting’s 1.4 million subscribers together with Time-Warner systems in New York, North Carolina and Florida at a time when the cable industry was undergoing consolidation in preparation for the battle-to-come with phone companies. Newhouse was also then a part owner of the Discovery cable TV channel.

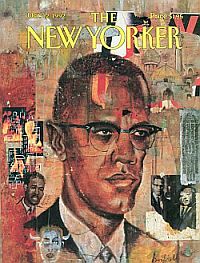

October 12, 1962 issue of The New Yorker with Malcolm X portrait.

Inside the magazine, Brown also made changes. She introduced color and photography giving the magazine a more modern layout with less type on each page. There was also more coverage of current events and hot topics, featuring more celebrities and business tycoons. The “Goings on About Town” section included short pieces throughout and a column about Manhattan nightlife. A new letters-to-the-editor page and the addition of authors’ bylines to the “Talk of the Town” section had the effect of making the magazine more personal.

|

Two Newhouse Books Felsenthal worked for five years on the Newhouse book, conducting some 430 interviews and producing a volume that offers a vast compendium of facts, quotes, and anecdotes. Her book includes great detail on Si Newhouse’s editorial proclivities and the lavish perks he bestowed on his editorial elite, with former editors and publishers talking candidly about their dealings with Newhouse, who is cast as cold and uncaring by several long-time editors. Still, Felsenthal portrays Newhouse as a businessman who made few mistakes, taking his father’s newspaper company to new heights with successful expansions in book and magazine publishing. |

By March 1998, the Newhouse family appeared to be streamlining its operation, and cutting away properties which had underperformed. One of these was the Random House publishing group, which by then included many well known and well respected imprints including: Alfred A. Knopf, Crown Publishing, Ballantine Books, Fawcett Books, Fodor’s, Modern Library, Pantheon Books, Orion, Vintage Books, and others. During its 18 years of ownership, the Newhouse family had expanded Random House from a $200 million-a-year publishing house with no properties overseas to world’s largest English language trade publisher with ports in England and Australia. But like others in the industry, Random House had struggled with heavy returns of unsold titles and marginal profitability. In 1996 it’s profits were generously estimated at $1 million on $1 billion in sales. However, as part of the privately-held Advance Publications empire, and not having to worry about quarter-to-quarter pressures of a publicly-held company, the Newhouse family could and did take the long view with Random House.Some believe Newhouse played a key role in pushing Random to bring on celebrity authors and blockbuster books that would do well in a more entertainment-driven marketplace. Random also went after celebrity authors, and paid them well to write their books with big advances – $2.5 million to former Clinton presidential adviser, Dick Morris; $5 million for Marlon Brando’s autobiography, and more than $6 million for Colin Powell’s autobiography.

Still, in Random House, the Newhouse organization did not find the cross-business opportunities – or “synergies” as some described them – that might have moved between the magazine and book businesses. One Newhouse editor at The New Yorker told the The New York Observer in March 1998: “The idea that The New Yorker has drawn any intellectual sustenance from Random House is ludicrous. There has never been an exchange of ideas and, even in business matters, like first serial rights. Random House has always been as firmly self-interested as the next publisher.” During the 18-year Newhouse tenure, Random House and the book business had changed, and with the web and new retailing patterns, more change was ahead. Si Newhouse and family, some believed, were just more comfortable in the magazine and newspaper business. “Si loves the media business and he loves it for the right reasons,” one publishing source told The Observer. “He genuinely loves owning things that make a contribution to a high level of intellectual discussion. But he is at core a businessman….” By 1997, Si and family had decided to sell Random, but they would not sell it to just anybody; there would have to be a genuine interest in the book business. When German bookseller Bertelsmann approached Newhouse with an interest in the company, negotiations began. Bertelsmann wanted a foothold in the American publishing business, and in the end paid more than $1 billion for Random House – $1.3 billion by one estimate.

“I think Si deserves a lot of credit,” said Thomas Maier, author of the 1994 book, Newhouse, summing up the Newhouse ownership of Random House to New York Times reporter Doreen Carvajal. “He…grew the business through acquisitions and by hiring some terrifically talented people. I think it’s very debatable whether they improved the quality or not. In some ways they did, and in other ways they ended a genteel, writer-oriented era in publishing in favor of a celebrity, media-driven realm. Was that a tide that could be bucked? Probably not.” Newhouse, in Maier’s view, played a key role in pushing Random to bring on more celebrity authors and blockbuster-type books that would do well in a more entertainment-driven marketplace. And that change helped draw in even bigger players like Disney and Murdoch.

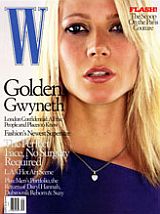

Sept 2001: Gwyneth Paltrow. |

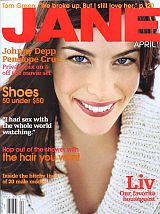

April 2011: Liv Tyler. |

In the magazine business, meanwhile, the Newhouse enterprise was still buying. In May 1998, the company acquired full control of Wired magazine, the San Francisco based technology/life style magazine. In 1999, additional magazines were bought from Disney through Fairchild Publications, a company Disney had acquired when it bought Cap Cities /ABC in 1995. Newhouse acquired three magazines in the Disney deal – W, Jane, and Women’s Wear Daily. W and Women’s Wear were fashion magazines, while Jane was oriented to the 18-to-34 year old market. Newhouse reportedly offered $650 million in the Disney/Fairchild magazine deal, outbidding the Hearst Corporation, a big rival in the magazine business. With the three mostly fashion additions, Newhouse now had control of more fashion advertising revenue than any of its rivals — worth hundreds of millions of dollars annually. Covers in these magazines during 1999, for example, featured celebrities such as: Lisa Kudrow, Natalie Portman, Courtney Love, Minnie Driver, Mariah Carey, Claire Danes — with others in that vein continuing through the early 2000s, such as the Gwyneth Paltrow and Liv Tyler covers shown above.

2000s: New World

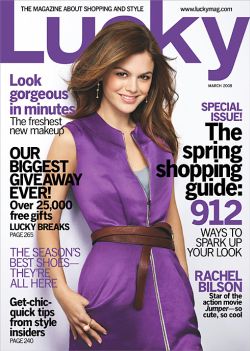

Actress Rachel Bilson on the cover of the March 2008 issue of “Lucky” magazine, a Newhouse success story in the otherwise tough 2000s.

On the magazine side, there were also additions, as well as a few subtractions. Lucky, a new creation, was launched in December 2000, cast as a shopping guide and style magazine primarily for women. Its articles focused on fashion – what to wear and how to wear it – and each issue featured a spread on some the cover girl’s favorite clothes and trends. Another magazine, Modern Bride, was acquired from Primedia for $52 million in 2002, and fit another slice of the Condé Nast upscale audience. In early 2003, Teen Vogue was launched as a another new Condé Nast magazine with Gwen Stafani on the cover of the first issue. Teen Vogue was basically conceived as a teenage version of Vogue magazine aimed at teenage girls. Focusing on teen fashion and celebrities, with related news and entertainment feature stories, it became a successful new magazine in the Newhouse/Condé Nast stable, soon reaching a circulation of more than one million. At the same time, three other magazines were closed in 2001 – Mademoiselle, Golf World, and Golf Digest. In the Cable TV arena, Advance and AOL/Time-Warner ended their cable partnership in 2002, as Advance changed the name of its cable operations to Bright House. By early 2008, before the economy went south, the Newhouse empire had revenues of more than $7 billion with more than 20,000 employees. The combined worth of Si and Donald Newhouse had been estimated by Forbes a few years earlier at around $15 billion.

Image & Style. Newhouse magazines during the 2000s continued with their celebrity-centric and fashion offerings, as well as their socially-trendy reporting. Vanity Fair had established itself since the 1990s as perhaps the top New York magazine on pop culture, fashion, and current affairs, and continued with that mix of fare through the 2000s.

Vogue’s Sept 2007 fashion issue, featuring actress and model Sienna Miller on its cover.

Fashion, of course, is a core part of the Newhouse /Condé Nast publishing and advertising world, with the venerable Vogue magazine and its iconic editor, Anna Wintour, among its biggest stars. Wintour, in fact, was famously played by Meryl Streep in the 2006 film, The Devil Wears Prada.

If that weren’t enough, a documentary film was made about Vogue’s famous annual fall fahion issue. The film, bearing the title, The September Issue, was released in 2009. It chronicled the production of what was then the largest issue in Vogue magazine history, the September 2007 issue, running some 840 pages thick, 727 pages of which were ads. The cover of that issue featured Sienna Miller along with its proudly proclaimed page count.

“We stand for a certain world,” Anna Wintour would later tell New York magazine writer Steve Fishman in a 2009 interview. “Women want to have pretty clothes. I mean, it’s a question of self-respect too.” In his New York article Fishman also quoted Wintour describing Vogue’s place in the publishing world as she pointed to some of the wares her magazine promoted: “… Wintour tells me about Ralph Lauren’s new collection of watches, which inspires her. They cost more, but they will last. ‘He wants to be part of the culture, and I feel the same way about Vogue: I want Vogue to be there, part of the culture,’ she says.”

|

|

|

|

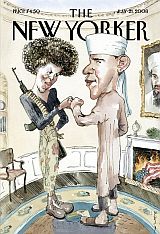

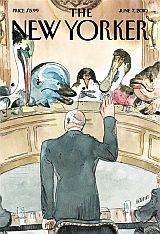

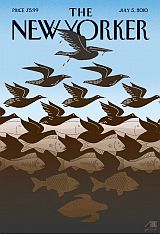

Over at The New Yorker, meanwhile, the engaging stories and cover art of that magazine continued to be much-loved features, though occasionally generating notice with cover art that hit certain sensitive political or controversial subjects. Among these, perhaps most famously, was a July 2008 cover, meant as satire, that used cartoon renditions of then presidential candidate Barack Obama and his wife, depicting them as flag-burning, fist-bumping radicals — she dressed as a revolutionary and he in muslim garb. The artist, Barry Blitt, defended his work, saying “the idea that the Obamas are branded as unpatriotic in certain sectors is preposterous. It seemed to me that depicting the concept would show it as the fear-mongering ridiculousness that it is.” Editor David Remnick explained that the satire was deliberate and purposely overboard in order to mock all the phony smears that were being leveled at the Obamas. Still, others – and notably Obama’s campaign at the time – thought the imagery was harmful. Rachel Sklar writing in the Huffington Post, noted: “presumably the New Yorker readership is sophisticated enough to get the joke,” but she worried about those who might use the “handy illustration” to continue to spread the very scare tactics and misinformation depicted. Other New Yorker covers during the 2000s captured economic problems such as “Red Death on Wall Street,” by artist Robert Risko that ran in the October 20, 2008 issue, or “S.O.S.,” by Christoph Niemann, that ran in the August 15/22, 2011 issue. Two New Yorker covers in 2010 hit BP’s Gulf of Mexio oil spill – one from the June 7, 2010 issue that showed a man in a suit testifying before a Congressional-like panel of oil-saturated marine animals, and five weeks later, offering a visual play on Escher-like imagery, titled “After Escher: Gulf Sky and Water,” by artist Bob Staake, which reportedly “lit up the blogosphere,” as Staake cleverly modified the original Escher to include oil-drenched Gulf wildlife, with a pelican at the top and a turtle at the bottom.

|

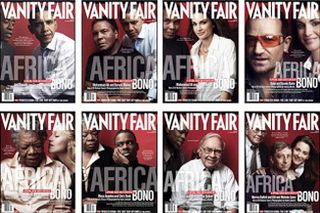

Creating The Buzz  Si Newhouse, buzz-maker.  Part of the sequence of 20 “celebrity pairs” used in Vanity Fair’s special Africa edition, July 2007. |

Hard Times at Newhouse

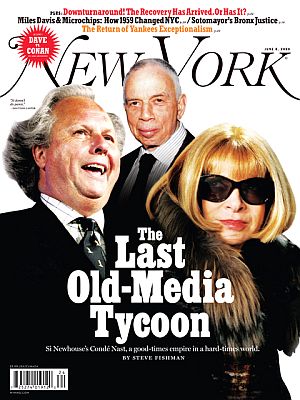

June 2009: New York magazine ran a cover story on part of the Newhouse empire, subtitled “Si Newhouse’s Condé Nast, a Good-Times Empire in a Hard-Times World.”

Yet hard times were taking a toll on the Newhouse publications and the family fortune. In the first three months of 2009, The New Yorker’s ad pages were down 36 percent, and at Vogue and Vanity Fair, around 30 percent. Wired’s were down by almost 60 percent. Between 2007 and 2009 Newhouse had closed nearly a dozen magazines, among them: Jane, House & Garden, Men’s Vogue, Golf for Women, Domino, Portfolio, Modern Bride, Elegant Bride, Gourmet, and Cookie. Some of these, however, retained an on-line presence. Fishman’s New York piece explained how Si Newhouse had grown up in the magazine business and loved magazines, and how it pained him personally to close them down. But the nature of the Newhouse business was changing, as Fishman;s piece explained. Some 40 percent of the family fortune now came from its stake in Discovery Communications, which ran cable and satellite TV networks with programs such as Discovery Channel, Animal Planet and TLC.

Cash Cow Blues. Newspapers – the stock and trade of the Newhouse rise – were also in trouble by this time. What was once the reliable center of the Newhouse empire – at least with respect to its revenue-generating power – had become something of an albatross by the mid- and late 2000s. Hit hard by the realities of the internet, some big Newhouse newspapers were bleeding badly. In 2008, the Newark Star-Ledger for one may have lost as much as $40 million. Circulation there had fallen by nine percent to 223,000 copies and newsroom staff cuts of 40 percent followed. In 2009, The Ann Arbor News was reduced more or less to a website, AnnArbor.com, with a print edition appearing just two days a week using a fraction of its former staff to run the website. Revenues for the Newhouse newspaper group plummeted 26 percent in 2009, to $1.3 billion, according to Ad Age. In 2010, the slide continued at some papers, as circulation at The Plain Dealer in Cleveland — one of the biggest of the Newhouse papers — was down 7 percent during the six-months of March-August 2010 to an average of 253,000 copies. More recently, in May 2012, it was revealed that The Times-Picayune daily newspaper in New Orleans, founded in 1837, would be reducing its print schedule, publishing a print edition three days a week while shifting more coverage on-line.

May 2012: The Times-Picayune of New Orleans announces print edition cutback and move to digital.

And at least in certain markets, newspapers still make good business sense. Curiously, among buyers of newspapers recently has been Warren Buffett, the billionaire investor who has frequently had a keen eye for what’s likely to make money in the future. His purchase of the Omaha World-Herald, where Buffett lives, may have been “one for the home town.” Yet, his May 2012 acquisition of Media General’s 63 newspapers in the southeast U.S. may suggest that local advertising revenue is alive and well, and possibly more. If nothing else, newspapers offer good bases for digital development and website expansion.

Back at Newhouse, meanwhile, “Advance Digital” is growing alongside of, and in some cases may eventually supplant, much of the company’s newspaper empire. The focus there is to build out a local news and information network of websites, each in alliance with one or more of the 25 Newhouse-owned newspapers presently affiliated with Advance Publications. The Advance Digital websites provide local information, breaking news, local sports, travel destinations, weather, dining, bar guides and health and fitness information. In its pitch to advertisers, showing a U.S. map with links to its 12 websites, Advance Digital says: “We are a leading network of local websites – we are affiliated with over 25 newspapers; we reach over 18.9 million consumers every month; and we have a large and diverse audience of educated and affluent professionals.”

Reddit.com logo.

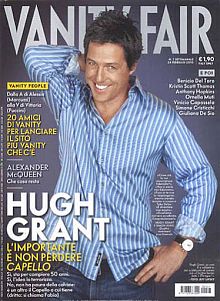

Actor Hugh Grant on the cover of Vanity Fair, Italy (Feb 2010), one of more than100 international Newhouse editions.

Whether the Newhouse magazines can make this move with success, however, is an open question, as other publishers have tried similar moves in the past attempting to link to television and film that have failed. One advantage in their favor, however, may be the top-shelf nature of the Newhouse magazines and their premium-brand content, offering strong appeal to upscale consumers and advertisers.

International Business. In the last few years, another Newhouse manager, Si’s cousin Jonathan Newhouse, now in his early 60s, has made Condé Nast International a Newhouse growth area. As of November 2010, he added Vogue in India and GQ in China. Condé Nast International now has more than 100 editions. The division also recently launched Condé Nast Restaurants, which plans to license the Vogue and GQ brands as eateries overseas.

Culture-Maker Still

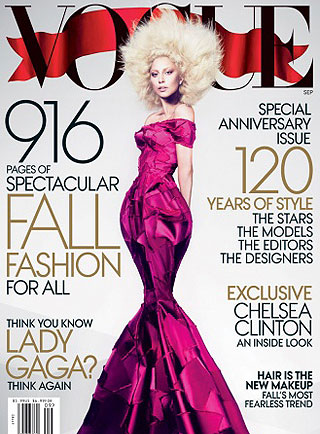

The Newhouse-owned Vogue magazine released its record-breaking, 916-page fall fashion issue in September 2012 with Lady Gaga on the cover.

For additional stories at this website on newspaper and magazine history, see for example: “Newsweek Sold!, 1961″ (on the Washington Post’s acquisition of Newsweek, Ben Bradlee/Phil Graham role, and more recent history from Newsweek’s demise to the Jeff Bezos acquisition of the Post); “FDR & Vanity Fair, 1930s” (politics & publishing during the New Deal era); “Murdoch’s NY Deals, 1976-1977″ (Rupert Murdoch’s newspaper & magazine growth, including his takeover of Clay Felker’s New York Magazine); and “Rockwell & Race, 1963-1968,” (exploring Norman Rockwell’s art on this topic at The Saturday Evening Post and Look magazine). Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 18 September 2012

Last Update: 6 December 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Empire Newhouse:1920s-2010s”

PopHistoryDig.com, September 18, 2012.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Sam Newhouse Sr. and wife Mitzi, possibly early 1970s. |

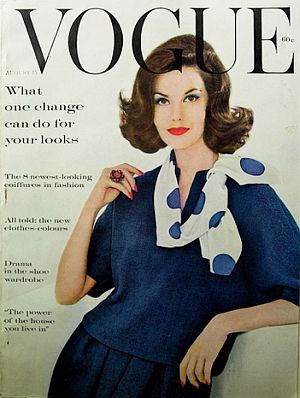

Vogue magazine, 15 August 1960, about a year after Newhouse acquired it and others. |

A sample cover of "Glamour" magazine, January 1971. |

March 1981: Actor Jack Nicholson on cover of Newhouse-owned “GQ” magazine. |

Actor Clint Eastwood on the cover of "Parade," the Sunday supplement magazine, October 23rd, 1983. |

Inaugural March 1991 issue of “Allure,” a Condé Nast publication that focuses on beauty, fashion, and women’s health, now with a circulation of 1 million plus. |

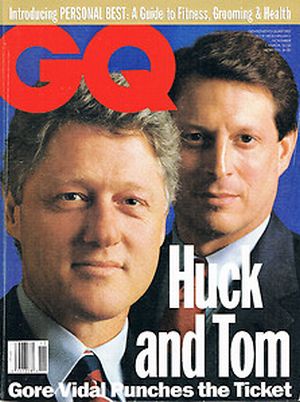

November 1992: Democratic candidates Bill Clinton and Al Gore are featured on CQ’s cover with a story by Gore Vidal – “Gore Vidal Punches the Ticket.” |

August 1993 Vanity Fair cover with model Cindy Crawford “shaving” famous lesbian singing star, k.d. Lang in drag, meant as a controversial statement. |

New Yorker cover of November 15, 2010, titled “Bumped,” by artist Barry Blitt, follows mid-term elections depicting President Obama in the Oval Office with Rep. John Boehner (R-OH), then expected to replace Nancy Pelosi as Speaker of the House. Boehner is shown offering his fist, while Obama extends his hand for a handshake. |

Milton Moskowitz, Michael Katz & Robert Levering, “Newhouse,” Everybody’s Business, An Almanac: The Irreverent Guide to Corporate America, San Francisco: Harper & Row Publishers, 1980, pp. 385-387.

“Condé Nast Publications,” Wikipedia.org.

“Buys Portland Oregonian; Newhouse Adds Coast Paper to Chain for $5,000,000,” New York Times, December 11, 1950.

“Newhouse Buys Alabama Papers; Pub-lisher Pays $18.7 Million for 2 Dailies, TV Outlet, and 3 Radio Stations,” New York Times, December 2, 1955.

“Newhouse Buys Oregon Journal; Estimated Price is $8 Million for Daily in Portland,” New York Times, August 5, 1951.

“The Newspaper Collector,” Time, July 27, 1962.

“Newhouse Buys Paper in Omaha; $40 Million World-Herald Bid is Accepted by Director,” New York Times, October 30, 1962.

U. S. Congress, House of Representa- tives, “Federal Responsibility for a Free and Competitive Press,” Hearings before the Antitrust Subcommittee of the House Committee on the Judiciary (investiga- tion of monopoly practices in the newspaper industry), 1963.

John A Lent, Newhouse, Newspapers, Nuisances: Highlights in the Growth of a Communications Empire, New York: Exposition Press, 1966.

“S.I. Newhouse and Sons: America’s Most Profitable Publisher,” Business Week, January 26, 1976.

Philip H. Dougherty Advertising; Condé Buys A Men’s Magazine,” New York Times, February 16, 1979, p. D-12.

“Samuel I. Newhouse, Publisher, Dies at 84; …Builder of an Empire in Newspapers and Broadcasting…,” New York Times, August 30, 1979, p. 1.

“Advance Publications, Inc.,” Funding Universe.com.

“Newhouse Acquires Booth Chain of Newspapers for $305 Million,” New York Times, November 9, 1979.

Jane Perlez, “Vanity Fair Sparks Sharp Reaction,” New York Times, Wednesday, March 30, 1983, p. C-20.

Richard H. Meeker, Newspaperman: S.I. Newhouse and the Business of News, New Haven, Connecticut: Ticknor & Fields, 1983.

Jonathan Friendly, “Newhouse’s Private Empire,” New York Times, Wednesday, October 12, 1983, p. D-1.

Frederick Ungeheuer, John Greenwald & David Beck, “Auditing the Grand Inquisitor,” Time, October 24, 1983.

Pamela G. Hollie, “Newhouse to Acquire 17% of The New Yorker,” New York Times, Wednesday, November 14, 1984, p. D-1.

Eric N. Berg, “Newhouse Makes Offer for the New Yorker,” New York Times, Wednesday, February 13, 1985, p. D-1.

Katherine Roberts and Walter Goodman, “Newhouse Wants The New Yorker,” New York Times, Sunday, February 17, 1985, Week in Review, p. 7.

Eric N. Berg, “Newhouse Purchasing the New Yorker,” New York Times, Saturday, March 9, 1985, p.1.

“Tina Brown,” Wikipedia.org.

Carol J. Loomis & Rosalind Klein Berlin, “The Biggest Private Fortune: Media Magnates Si and Don Newhouse Control a $7.5-Billion Empire. It’s a Tightly Private Show, But There’s No Hiding Wealth This Big,” Fortune, August 17, 1987, p. 60.

Herbert Mitgang, “Random House Buys Crown,” New York Times, August 16, 1988.

Geraldine Fabrikant, “Si Newhouse Tests His Magazine Magic,” New York Times, September 25, 1988.

Albert Scardino, “Big Spender at Vanity Fair Raises the Ante for Writers,” New York Times, April 17, 1989.

N. R. Kleinfield, “The Media Business; Heads Have a History of Rolling at Newhouse,” New York Times, November 2, 1989.

Maggie Mahar, “All in the Family,” Barron’s, November 27, 1989.

Milton Moskowitz, Michael Katz & Robert Levering, “Newhouse,” Every- body’s Business: A Field Guide to the 400 Leading Companies in America, New York: Doubleday/Currency, 1990, pp. 359-361.

Deirdre Carmody, “Tina Brown to Take Over at The New Yorker,” New York Times, July 1, 1992.

Geraldine Fabrikant, “The Media Business; Vanity Fair Is Hot Property, But Profit Is Open Question,” New York Times, July 13, 1992.

“New Yorker’s New Face: Malcolm X,” New York Daily News, Monday, October 5, 1992.

“GQ,” Wikipedia.org.

Geoffrey Foisie and Rich Brown, “Time Warner Entertainment: A Big MSO Gets Bigger,” Broadcasting & Cable, September 19, 1994, p. 12.

Tim Jones, “Unwanted Biography Reveals Newhouse,” Chicago Tribune, November 29, 1994.

Patrick J.Pain & James R. Talbot (eds), “Advance Publications, Inc.,” Hoover’s Handbook of American Companies 1996, Austin, Texas: The Reference Press, Inc., August 1995, pp.48-49.

Thomas Maier, Newhouse: All the Glitter, Power, & Glory of America’s Richest Media Empire & the Secretive Man Behind It, New York: St. Martin’s Press,1995, 446pp.

Linda Fibich (Newhouse News Service’s national editor), Book Review, “The Newhouse Media Empire,” American Journalism Review, January/February 1995.

Sandra McElwaine, “Newhouse: Book Reviews,” Washington Monthly, Jan-Feb, 1995.

“American City Business Journals,” Wiki-pedia.org.

Jeannine F. Hunter, “Cox Communica- tions May Swap Myrtle Beach, S.C., System to Time Warner,” Knight-Ridder/Tribune Business News, March 28, 1996.

Geraldine Fabrikant, “Disney to Sell Publications Inherited With Capital Cities,” New York Times, January 29, 1997.

Geraldine Fabrikant, “Book Deal: The Seller; ‘Planning Our Future,’ Newhouse Brothers Say,” New York Times, March 24, 1998.

Paul D. Colford, “Newhouse Magazines Bask in Glow of Multiple Nomina- tions,”Los Angeles Times, March 26, 1998.

Doreen Carvajal, “Media; Newhouse’s Legacy Lives In Publisher,” New York Times, March 30, 1998.

Nora Rawlinson, “The Random House Acquisition: An Interview with S.I. Newhouse,” Publisher’s Weekly, April 3, 1998.

Warren St. John, “So Why Did Newhouse Sell Random House to Bertelsmann Boys?,” The New York Observer, March 30, 1998.

Lori Leibovich,. “Wired Nests with Condé Nast: Will the Magazine’s New Owners Dull its Edge?,” Salon.com, May 8, 1998.

Advance Publications, International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 19. St. James Press, 1998.

Carol Felsenthal, Citizen Newhouse: Portrait of a Media Merchant , New York: Seven Stories Press, 1998, 608pp.

Carol Felsenthal, Citizen Newhouse: Portrait of a Media Merchant, Chapter One, New York Times.

“Citizen Newhouse,” (Autor, Carol Felsenthal on her book), C-SPAN Video.org, January 27, 1999.

Felicity Barringer, The Media Business, “Fashion Magazine Industry Consolidates with a Big Deal,” New York Times, August 25, 1999.

Christine Schiavo, “Chain Buys Express-times Of Easton In Newhouse Group, Newspaper Joins Star-Ledger, Parade Magazine,” The Morning Call (Allentown, PA), July 6, 2000.

Alex Kuczynski, “The Media Business; Goodbye to Mademoiselle: Condé Nast Closes Magazine,” New York Times, October 2, 2001.

Leslie Bennetts, “The Unsinkable Jennifer Aniston,” Vanity Fair, Septem- ber 2005.

Matthew Flamm, “Advance Publications at Crossroads: Newhouse Family’s Business Units Fight to Keep up with Times as Succession Changes Loom,” CrainsNew York.com, November 21, 2010.

“Samuel I. Newhouse: Publishing Giant, Staten Island Legacy,” Staten Island Advance, Sunday, March 27, 2011,

“Staten Island Advance,” Wikipedia.org.

Richard Pérez-Pena, “Can Si Newhouse Keep Condé Nast’s Gloss Going?,” New York Times, July 20, 2008.

“Vanity Fair at 25: The Covers,” VanityFair .com, September 26, 2008.

“Condé Nast Publications,” Wikipedia.org.

“W ( magazine),” Wikipedia.org.

Howard Kurtz, “When Art Gives Offense,” Washington Post, Tuesday, July 15, 2008.

Stephanie Clifford, “Condé Nast Closes Gourmet and 3 Other Magazines,” New York Times, October 5, 2009.

“Shrinking Condé Nast “(a nifty interactive graphic on Condé Nast publications), New York Times, October 6, 2009.

Michael Hogan, “Our Man Dominick,” Vanity Fair, November 2009.

“Sexy Celeb Magazine Covers,” NY Post.com, September 10, 2010.

“Top 10 Nude Magazine Covers,” Time.com, February 28, 2012.

Jeff Bercovici, “Condé Nast Swaggers Into the Entertainment Business,” Forbes, October 11, 2011.

Jeff Bercovici, “Condé Nast’s Open Secret: SI Newhouse No Longer In Charge,” Forbes, November 21,2011.

Ivey DeJesus, “Sara Ganim, Patriot-News Staff Awarded Pulitzer Prize for Coverage of Jerry Sandusky Case,” The Patriot-News, Tuesday, April 17, 2012.

Steve Jordon, World-Herald Staff Writer, “Buffett to Buy 63 Newspapers,” Omaha .com, May 18, 2012.

Ned Martel, “The Hope of Heft: In Tough Times, Vogue’s Fantasies and Huge Size Life Spirits – And Forecasts,” Washington Post, August 29, 2012, p. C-1.

Other Stories at This Website on Newspaper & Magazine Topics:

Jack Doyle, “Newsweek Sold!, 1961” (history of Washington Post’s acquisition of News-week), PopHistoryDig.com, April 16, 2008.

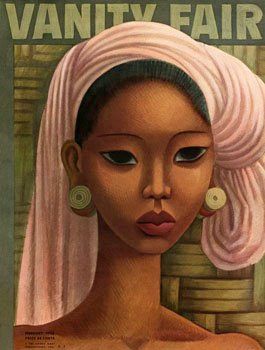

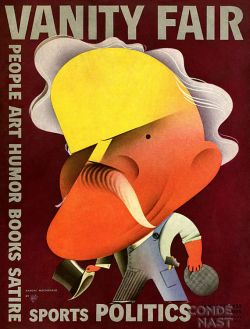

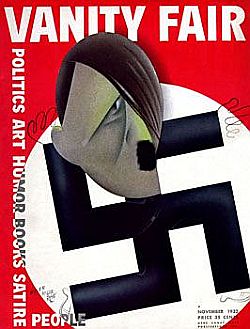

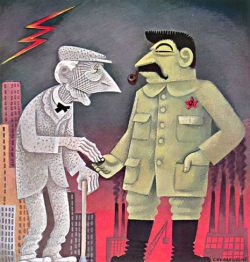

Jack Doyle, “FDR & Vanity Fair, 1930s” (politics & publishing during the New Deal era), PopHistoryDig.com, November 2, 2009.

Jack Doyle, “Murdoch’s NY Deals, 1976-1977” (Rupert Murdoch’s newspaper & magazine growth), PopHistoryDig.com, Septem-ber 25, 2010.

Jack Doyle, “Rockwell & Race, 1963-1968” (Rockwell art at Saturday Evening Post & Look magazines), PopHistoryDig.com, Sep-tember 23, 2011.

Jack Doyle, “John Clymer’s America: The Saturday Evening Post,” PopHistoryDig .com, March 30, 2020 (history & selection of John Clymer’s cover art).

Jack Doyle, “Falter’s Art, Rising: Saturday Evening Post” (1940s-1960s), PopHistory Dig.com, April 19, 2015 (cover art of John Falter, whose work has been featured on Antiques Roadshow and appraised at Sothebys and other auction houses).

Jack Doyle, “U.S. Post Office, 1950s-2011,” (magazine cover art from the 1950s helps frame community role & importance in “postal values” politics, etc.), PopHistoryDig .com, September 29, 2011.

Jack Doyle, “Rockwell & Race, 1963-1968,” (Norman Rockwell, civil rights & related magazine cover art history), PopHistoryDig .com, September 23, 2011.

Jack Doyle, “Lucy & TV Guide: 1953-2013,” PopHistoryDig.com, January 26, 2015 (story featuring history Lucille Ball’s 43 TV Guide covers that helped make Walter Annenberg’s TV magazine one of the top sellers in the country).