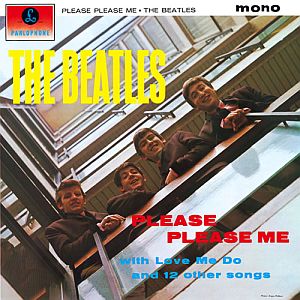

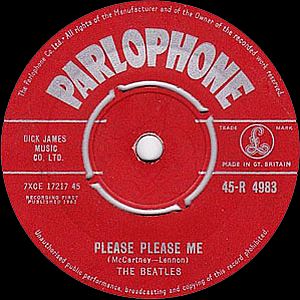

The Beatles’ first No. 1 U.K. hit, “Please Please Me,” came in Feb 1963 on Parlophone records. Click for digital.

In February 1963, “Please Please Me” was the song that first sent the Beatles’ music to the top of the U.K. music charts. It was their first No. 1 hit. It was also the song that energized “Beatlemania” in the U.K. – the screaming crowds that began besieging the Beatles at their stage appearances, generating media attention far and wide.

“Please Please Me,” in fact, was the tipping point – the take-off song that changed everything. Within a year of this song’s release, the Beatles would be a worldwide phenomenon, their music selling practically everywhere.

True, the Beatles’ first hit song was “Love Me Do,” which rose to No.17 on the U.K. charts in November 1962. But “Please Please Me,” their second single, was the Beatles’ first popular “hard rocking” song; the song that captured their youthful exuberance and musical drive. It was also the song that first offered that unique “Beatles’ sound”– an appealing mix of young male vocals in sync with driving guitars. “Please Please Me” captured that sound in an aggressive and engaging way. It was feel good music that was fresh, open, and hopeful. The public ate it up.

John Lennon sang lead and played harmonica on the song, George Harrison played lead guitar, Paul McCartney was on bass, and drummer Ringo Starr delivered the back beat. McCartney and Harrison also supplied the harmony and background vocals. It was a sound the world hadn’t quite heard before – and a sound, as time would tell, that would turn music to gold.

1963: George Martin in sound booth at Abbey Road studios with the Beatles in the background. Click for his book.

Music Player

“Please Please Me”-1963

Initially, however, “Please Please Me,” as originally written by John Lennon, didn’t have the chops to make it as a No. 1 hit – at least not in the eyes of George Martin, the person then in control of the Beatles’ fate in their first London recording sessions. In fact, “Please Please Me” almost didn’t make it at all.

In the U.S., meanwhile, this song also had something of a tortured history. Although it was released in America in early 1963 as it had been in Britain, it went largely unnoticed. “Please Please Me” would not fully emerge as a U.S. hit until more than a year later, in March 1964, when it would join four other Beatles’ songs to occupy the top five positions on the U.S. Billboard charts. But the story of “Please Please Me” in America captures some of the confusion, bungled business opportunities, and the general whirlwind that came with the Beatles euphoria in those crazy early days. More on that in a moment.

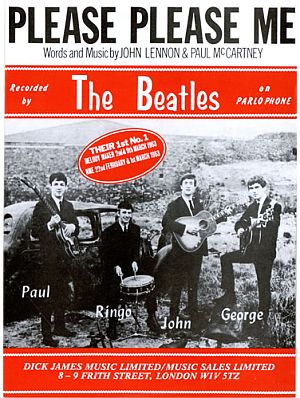

Sheet music cover for the Beatles’ “Please Please Me” issued by Dick James Music, Ltd., London.

Paul McCartney pointed back to Orbison’s style. “If you imagine [Please Please Me] much slower,” McCartney said of the song, “which is how John wrote it, it’s got everything. The big high notes, all the hallmarks of a Roy Orbison song.”

In 1962 Lennon’s song was offered initially at the Beatles’ first London studio session in its slower form. George Martin, the studio engineer and manager of EMI’s Parlophone label, and the guy who had signed the Beatles in 1962, did not like Lennon’s song when he first heard it. He found it too slow and reportedly called it “a dirge” at one point. He suggested the song’s tempo be sped up and that the Beatles try a different arrangement. Reportedly, Martin also played a sped-up taped version of the song from an earlier recording that served as something of an “ah-ha” moment for the group. But Martin wanted the Beatles to record another song at their next session at Abbey Road studios on November 26th, 1962, one the Beatles had not written themselves.

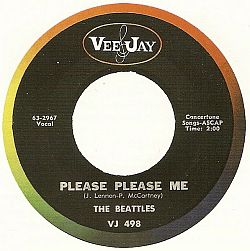

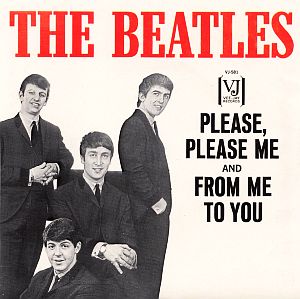

Early U.S. Vee-Jay single of Beatles’ “Please Please Me,” released in 1963, distinguished by ‘Beattles’ misspelling, later corrected. Click for vinyl.

In the U.S., meanwhile, George Martin had sent a copy of “Please Please Me” to EMI’s U.S. subsidiary, Capitol Records, in January 1963, urging executives there to distribute Beatles’ songs in the U.S. They declined, saying famously: “We don’t think the Beatles will do anything in this market.” Atlantic Records was also offered a chance to distribute “Please Please Me” in the U.S., but they also declined. At that point, other record labels began looking at the Beatles’1963 songs for U.S. release. One of these labels was Vee-Jay out of Chicago, an African American-owned label founded in the 1950s specializing in blues, jazz, rhythm and blues, and rock and roll.

Brian Epstein, who discovered the Beatles and became their manager, negotiated early business deals and arranged for publicity. Click for book.

Back in Britain in 1963, “Please Please Me” was doing so well that Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein pulled the Beatles off their tour schedule to record their first album, naming it Please Please Me to capitalize on the popularity of the single. Some 14 songs – including “I Saw Her Standing There” as the lead track – were compiled for that album in one day after nine hours of recording over three sessions. The new Please Please Me album was released in late March 1963. Within four weeks it would be No.1 on the U.K. albums chart, remaining in that position for 30 weeks. New Beatles’ singles were also released in the U.K. through 1963, and these resulted in three more No. 1 hits: “From Me to You” w/ “Thank You Girl” in April 1963; “She Loves You,” w/ “I’ll Get You” in August 1963 ( which achieved the fastest sales of any record in the U.K. up to that time, selling 750,000 copies in less than four weeks); and “I Want To Hold Your Hand” w/ “This Boy” in November 1963, which had 1 million advance U.K. orders.

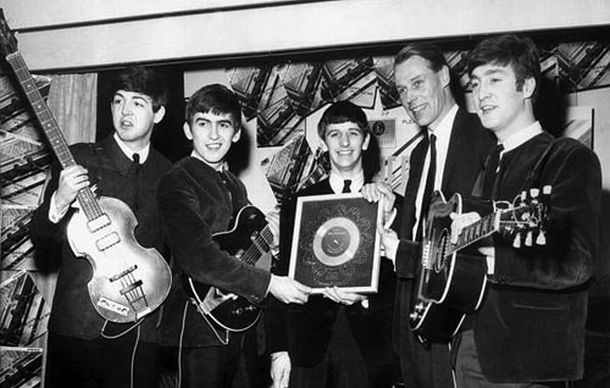

April 1963: Beatles with George Martin at EMI House in central London receiving their first silver disc for sales of more than 250,000 copies of “Please, Please Me.” Click for 2017 book, “Maximum Volume: The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin, The Early Years, 1926–1966”.

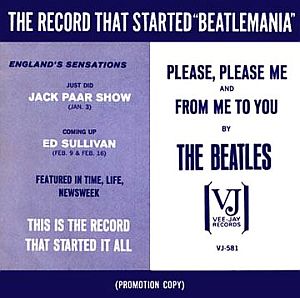

Vee-Jay’s promotional cover sleeve for Beatles’ ‘Please Please Me’ single following Jack Paar show, Jan 1964.

Vee-Jay records, for its part, seeing the rising tide for all things Beatles, decided to take another shot at “Please Please Me,” and in mid-January 1964 re-issued the single, this time, with “From Me To You” on the “B” side. Some of Vee-Jay’s promotional record sleeves for the single featured headlines printed on the jacket that read: “The Record That Started Beatlemania,” and other text description noting the Beatles’ clip on The Jack Paar Show, their upcoming Ed Sullivan Show appearances, and press coverage in Time, Life and Newsweek magazines. “This Is The Record That Started It All,” said the Vee-Jay record sleeve. By January 25, “Please Please Me” finally entered the American Billboard chart at No. 69, soon rising to No. 1. Vee-Jay would sell at least 1.1 million copies of “Please Please Me” in its second offering, and would also sell at least four other Beatles’ singles, as well as the Beatles’ first U.S. album, Introducing…The Beatles, which came out ten days before Capitol’s Meet the Beatles!, also in January 1964.

Cover sleeve for re-issued single of Beatles’ “Please Please Me” in America by Vee-Jay Records. Click for collectible book.

“Please Please Me” may not be regarded as the Beatles’ best song ever by music critics or many of their fans, but it is certainly among the most important for launching their career, energizing their early style, and showing how adaptable and creative they could be when faced with criticism in the studio. In a special Rolling Stone magazine supplement of November 2010 reviewing the Beatles’ 100 greatest songs, “Please Please Me” is ranked at No. 20. Today, the song is still sold and downloaded by fans via Amazon.com, Apple’s iTunes music store, and other music sellers. For other stories on the Beatles at this website see “Beatles History: 12 Stories,” a sub-directory page with additional choices. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 1 February 2013

Last Update: 14 February 2019

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/PopHistoryDig

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Please Please Me, 1962-1964,”

PopHistoryDig.com, February 1, 2013.

____________________________________

Beatles Music at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

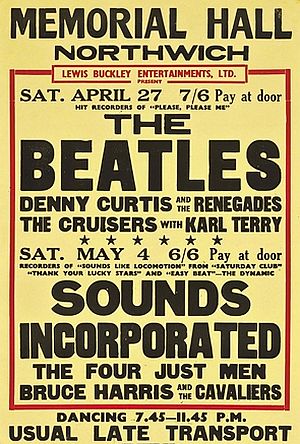

April 1963 poster for concert in Northwich, England with the Beatles at the top of the bill not long after “Please Please Me” hit the top of the charts. Small print above their name reads “Hit recorders of ‘Please Please Me’.” Poster was later sold at Christies in London, 2012. |

“The Beatles,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, Rolling Stone Press, New York, 3rd Edition, 2001, pp. 56-59.

Greil Marcus, “The Beatles,” in Anthony DeCurtis and James Henke, with Holly George-Warren (eds), The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock n Roll, New York: Random House, revised edition, 1992, pp. 209-222.

Frederick Lewis, “Britons Succumb to ‘Beatlemania’,” New York Times Magazine, December 1, 1963.

Lawrence Malkin, “Liverpudlian Frenzy; British Beatles Sing Up a Teen-Age Storm,” Los Angeles Times, December 29, 1963, p. G-4.

Jack Gould, “TV: It’s the Beatles (Yeah, Yeah, Yeah); Paar Presents British Singers on Film,” New York Times, Saturday, January 4, 1964, Business, p 47.

CBS, Inc., Press Release, “The Beatles to Make Three Appearances on Sullivan Show,” February 3, 1964.

Richie Unterberger, Beatles Song Review, “Please Please Me,” AllMusic.com.

“Please Please Me” (song), Wikipedia.org.

“The Beatles 100 Greatest Songs,” Rolling Stone, November 2010.

Bill Harry, The Beatles Encyclopedia: Revised and Updated. London: Virgin Publishing, 2000.

“Introducing… The Beatles,” Wikipedia.org.

Dennis McLellan, “Alan W. Livingston Dies at 91; Former President of Capitol Records,” Los Angles Times, March 14, 2009.

Jack Doyle, “Beatles’ Closed-Circuit Gig, March 1964″(Beatles’ first U.S. concert appearance in Washington, DC & related U.S. theater showings), PopHistoryDig.com, July 9, 2008.

Jack Doyle, “Dear Prudence, 1967-1968″(Beatles’ retreat in India & song trove developed thereafter), PopHistoryDig.com, July 27, 2009.

Jack Doyle, “Beatles in America, 1963-1964” (frenetic early years of Beatles’ popularity & music success) PopHistoryDig.com, September 20, 2009.

__________________________