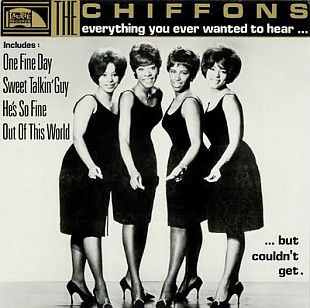

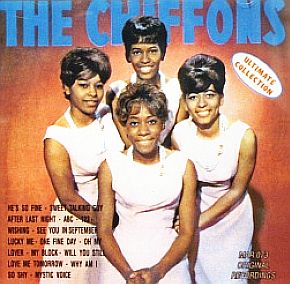

In 1963-64, The Chiffons put four songs on the Top 40 list, including “He’s So Fine,” a No.1 hit. Click for CD.

They were named The Crystals, The Shirelles, The Ronettes, and more. A few lone performers with and without female backup, also carried the “girl group” sound, and were considered a part this genre.

The distinctive sound of the girl group songs filled the air in those years, and seemed to be everywhere. The music spawned the sales of millions of records, creating a number of millionaires – though often not the performers themselves, who were frequently short-changed and manipulated in the process. More on that later.

Jacqueline Warwick’s 2007 book, “Girl Groups, Girl Culture,” with Shirelles on cover. Click for book.

Music critic Greil Marcus, writing of the girl groups in 1992 for The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, has noted: “The music was perhaps the most carefully, beautifully crafted in all of rock and roll – one reason why none of the twenty or so best records in the genre have dated in the years since they were made.” Now, more than 50 years old at this writing, the girl group music of the 1960s continues to have wide appeal and staying power.

According to some sources, there were over 1,500 girl groups that recorded in the 1960s. Of these, about two dozen or so went on to become significant hit makers. What follows here is an overview of some of the more prominent girl groups that emerged during the 1958-1966 period, along with a healthy sampling of songs from that era (more than a dozen), and some description of the songwriters, producers, and businesses involved in the music making.

Among the earliest of the girl groups were The Chantels with their powerful 1957-1958 hit, “Maybe,” featuring Arlene Smith singing lead. The group was established in the early 1950s by five girls, then students at St. Anthony of Padua school in The Bronx.Music Player

“Maybe”-1958

The original five members of The Chantels consisted of Arlene Smith (lead), Sonia Goring, Rene Minus, Jackie Landry Jackson, and Lois Harris. By the summer of 1957 The Chantels were signed by record producer George Goldner, owner of End Records. Their second single, “Maybe” was released in December 1957, and by January 1958 it became a top hit, reaching No. 15 on the Billboard chart and No.2 on the R & B chart. “Maybe” sold over one million copies and was awarded a gold disc. One profile of the group in liner notes for the PBS collection, The Doo Wop Box, noted: “Their records were not terribly sophisticated from a production standpoint, but then just listen to Arlene Smith’s voice and tell us if you really need anything else.” Smith was 16 years old when “Maybe” was recorded. In 2010, Rolling Stone ranked the song No. 199 on its list of The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.

However, The Shirelles, the girl group shown on the book cover above, and in later years on the album cover at left, are often regarded by rock historians as the opening act of the 1960s “girl group era,” and perhaps more representative of the girl group sound that followed in those years.

Music Player

“Will You Love Me Tomorrow?”-1960-61

Although the Shirelles had recorded a few songs as early as 1958, their hits didn’t start coming until 1960. Among their first popular songs was “Tonight’s The Night,” co-written by lead singer, Shirley Owens, a song that entered the Top 40 in mid-October 1960. “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” was a Shirelles’ No. 1 hit of December 1960-January 1961 that remained in the Top 40 for 15 weeks. During 1961-1962, four more Top Ten hits followed for the Shirelles: “Dedicated to The One I Love,” a No. 3 hit in February 1961; “Mama Said,” a No. 4 hit in May 1961; “Baby It’s You,” a No. 8 hit in January 1962 written by Burt Bacharach, Hall David and Barney Williams; and “Soldier Boy,” a No. 1 hit in March-April 1962. In all, over a two-year span, The Shirelles would put 11 hits in the Top 40, and five in the Top Ten.

The Shirelles ascendency came primarily in the early 1960s, during the “Kennedy years,” a time when America was riding high on the promise of a new young president named John F. Kennedy. And despite the Cold War clench and very serious civil rights issues then emerging, the popular music of the day, including the Shirelles’ songs and those of other girl groups, added a certain buoyancy and optimism to that era’s soundtrack.

|

The Shirelles “Tonight’s the Night” |

The Shirelles began as four high school friends in Passaic, New Jersey – Shirley Owens, Doris Coley, Addie “Micki” Harris, and Beverly Lee. They originally formed under another name in 1958 and were first signed by Florence Greenberg, who later ran the Scepter record label. Greenberg brought in producer Luther Dixon, who added string arrangements that improved the Shirelles’ sound, helping them produce the hit songs “Tonight’s the Night” and “Dedicated to the One I Love.”

Music Player

“Baby It’s You”-1962

Their big hit, “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” was written by Carole King and Gerry Goffin – one of the famed Brill Building song-writing teams in New York city, where a steady stream of pop hits originated during the 1950s and 1960s (see sidebar later below). “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” is sometimes credited as the first major girl group hit of the rock era and was also the first all-girl song to ever hit Billboard’s No.1 position. The song’s lyrics also ventured into new social territory raising the question all girls wanted answered after one night’s romance. Reviewing the song for AllMusic.com, Bill Janovitz has observed:

…The song is a masterpiece of pop songcraft… [King and Goffin] deftly handle controversial subject matter: the long-term concerns of a young woman involved in a physical consummation of love. Goffin’s lyrics address the issue in a direct manner, neither ham-fisted nor nudging with innuendo. The artful lyric is simply conversational; polite conversation — ladylike: “Is this a lasting treasure/ Or just a moment’s pleasure?” What a stunning couple of lines. Faced with the restrictions of early-’60s AM pop radio both in content and song length, King and Goffin squeeze an impressive amount of substance and significance from an economical, 14-syllable couplet. We realize that this very human need, this act of love, can be perceived as a meaningless satisfaction of physical desire, devastatingly disappointing to another who experiences the same moment as a consummation of a deep emotional commitment. These mere two lines sum up the impact that two people can have on each other’s feelings. “Tonight with words unspoken,” sings the narrator, “You say that I’m the only one.” Words unspoken? She is vulnerable, perhaps kidding herself, and she knows it; she is wishing for the best…

Music Player

“Please Mr. Postman”-1961

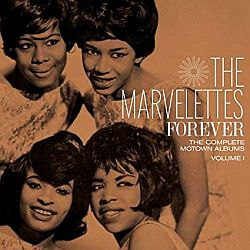

Also in the early 1960s came The Marvelettes, five girls from a Michigan high school glee club – Gladys Horton, Katherine Anderson, Wanda Young, Georgeanna Tillman and Juanita Cowart (with some changing personnel). They signed a Motown Records contract on the Tamla label in 1961.

Motown was the black-owned record label founded by Detroit’s Berry Gordy. A former auto assembly-line worker, Gordy began Motown with a $700 loan in 1959 and built it into a recording empire using three adjoining Detroit row houses as his studio. By 1964, Motown was the nation’s largest independent producer of 45-rpm records, selling 12 million records a year, with Motown girl groups accounting for an important share of that total.

The Marvelettes were the first girl group act of Motown Records, and the first Motown group with a No. 1 hit – “Please Mr Postman” — which hit the No. 1 spot on December 11, 1961. It stayed on the pop charts for nearly six months. “Mr Postman,” later covered by the Beatles, was followed by several other Marvelettes’ Top 40 hits, including three more in 1962 – “Twistin` Postman” at No. 34; “Playboy” at No. 7; and “Beachwood 4-5789” at No. 17. “Too Many Fish in the Sea” was a No. 25 hit in 1964, and “Don’t Mess With Bill” cracked the Top Ten at No. 7 in 1966. Another Marvelettes song that received some attention on the R&B charts, reaching No. 24 in the spring of 1963 — though is much better than that — is “Forever,” with Wanda Young Rogers singing lead in a moving and bravura performance (sampled later, at bottom of story).

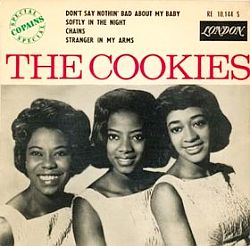

Among other groups sometimes considered as part of the 1960s’ girl group era were The Exciters, The Sensations, The Cookies, and The Paris Sisters. In October 1961, Priscilla, Albeth, and Sherrell Paris of San Francisco had a No. 3 hit, “I Love How You Loved Me,” and another Top 40 hit in March 1962, “He Knows I Love Him Too Much.” In February 1962, The Sensations of Philadelphia had a No. 4 hit with “Let Me In” on Chess Records’ Argo label, with Yvonne Mills Baker singing lead.

Music Player

“Tell Him”-1962-63

In December 1962-January 1963, The Exciters, a three person group with one male, scored with a Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller tune, “Tell Him,” which rose to No.4 and two decades later was used on The Big Chill soundtrack. Carole King and Gerry Goffin wrote for The Cookies girl group, a Brooklyn, New York threesome of Dorothy Jones, Ethel McCrea, and Margaret Ross, helping them produce the No. 17 hit, “Chains,” in the fall of 1962. The Cookies also sang backup vocals on the 1962 Little Eva hit song, “The Loco-Motion” (also by King/Goffin). But in early 1963, the Cookies scored a Top Ten hit with another King/Goeffin tune, “Don’t Say Nothin’ Bad About My Baby,” which rose to No.7 on the Billboard chart.

Music Player

“South Street”-1963

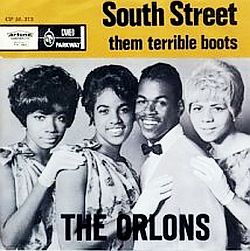

Another of the early 1960s groups were the Orlons – first formed as an all girl group in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the 1950s, but later added one male. Rosetta Hightower sang lead for the group, joined by Shirley Brickley, Marlena Davis and Stephen Caldwell. The Orlons had three Top Ten hits in 1962-63 – “The Wah-Watusi,” No. 2 in June 1962; “Don’t Hang Up,” No. 4 in the fall of 1962; and “South Street,” No. 3 in 1963.

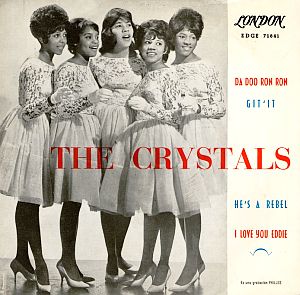

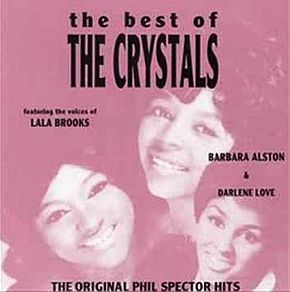

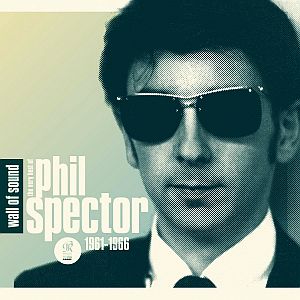

Girl group record producer Phil Spector had his first million-dollar payday in the early 1960s with The Crystals.

Enter Phil Spector

During the 1960s, the “girl group sound” began to be influenced and molded by a young record producer named Phil Spector who had previously recorded in the late 1950s with his own short-lived group, The Teddy Bears. Spector would become famous in the 1960s for his lavish instrumentation of girl group and other pop recordings; a technique that came to be known as “the wall of sound.” He became a master at composing appealing orchestral-like treatments for rock songs, giving them a full, lush sound with little “empty” air. He would later call these productions “little symphonies for the kids.” Spector was also a control-room maestro who became skilled at multi-tracking which he used to craft his “wall-of-sound” productions. “Whenever you hear a ‘60s-era production with echoey voices, five or six guitar parts, nearly as many keyboards, and perfectly aligned maracas and other percussion shaking and rattling underneath, it’s safe to assume that the enigmatic Spector created it, or inspired it,” writes Tom Moon in his book, 1,000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die.

The Crystals were the hot girl group in 1961-62 with hits such as: "Uptown," “He’s A Rebel” and “Da Doo Ron Ron,” which are sampled below.

Music Player

“Uptown”-1962

The Crystals, in any case, came on strong in the 1961-1963 period with a series of hits, including: “There’s No Other Like My Baby” (1962, No. 20); “Uptown” (1962, No. 13); “He’s A Rebel”(1962, No.1); “Da Doo Ron Ron”(1963, No. 3); “Then He Kissed Me” (1963, No. 6); and “He’s Sure the Boy I Love” (1963, No.11). The Crystals made Spector a millionaire; he was 21 years old.

Initially, the Crystals had formed in 1961 with five girls, most of them just graduating from high school – Barbara Alston, Mary Thomas, Dolores “Dee Dee” Kenniebrew, Myrna Girard and Patricia “Patsy” Wright. Their first hit was November 1961’s “There’s No Other Like My Baby,” co-written by Spector and Leroy Bates, with Barbara Alston on lead vocals. This song had been recorded on the evening of three of the girls’ high school prom, as they came to the studio still wearing their prom dresses. The Crystals’ next hit, “Uptown,” was written by Brill Building songwriters Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, and it included a little attitude and some class issues woven into the lyrics. Spector added flamenco guitar and castanets. But “Uptown” was upbeat in sound, featuring Barbara Alston on lead, and it became a top hit. After “Uptown,” one of the group’s members, Myrna Girard became pregnant and was replaced by Dolores “LaLa” Brooks.

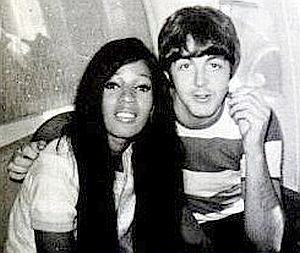

Darlene Love with Phil Spector, 1960s.

Music Player

“He’s A Rebel”-1962

Reportedly, the real Crystals were unable to travel from New York to Los Angeles fast enough to suit Spector, who was then racing to beat Vicki Carr to market with her version of the song. Instead, Spector used Darlene Love and the Blossoms to record “He’s A Rebel” as The Crystals, with Love in the lead, though uncredited. “He’s a Rebel” hit No. 1 in November 1962. The “Crystals” follow-up single –“He’s Sure the Boy I Love,” which hit No. 11 — also featured Love and The Blossoms, again uncredited. (See documentary, “20 Feet From Stardom,” for Love and others.)

Dolores “LaLa” Brooks with Phil Spector, 1960s.

Music Player

“Da Doo Ron Ron”-1963

Upon hearing the final playback of “Da Doo Ron Ron” in the studio, Spector reportedly remarked to Sonny Bono (later of “Sonny & Cher” fame, but then a production assistant) — “That’s gold. That’s solid gold coming out of that speaker.”

The follow-up Crystals’ single, “Then He Kissed Me,” also cracked the Top 10. Both of the 1963 hits – “Da Doo Ron Ron” and “Then He Kissed Me” – were co-written by Phil Spector with Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich. The lead vocals were sung by LaLa Brooks.

The Crystals, however, weren’t the only girl group Spector was working with. He also produced songs for the earlier-mentioned San Francisco group, The Paris Sisters. And once performers were signed with Spector, he would sometimes use them interchangeably with other groups, or as background singers, or for specially-created groups to put out one or two songs. Bob B. Soxx and the Blue Jeans, for example – with Darlene Love, Fanita James and Bobby Sheen – had two Top 40 hits for Spector’s Philles label in 1962 and 1963 – “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah,” No. 8 in December 1962, and “Why Do Lovers Break Each Other’s Heart?,” No. 38 in March 1963.

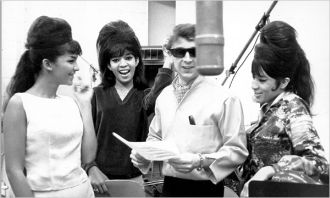

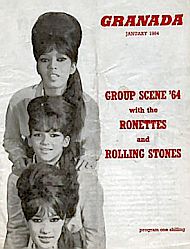

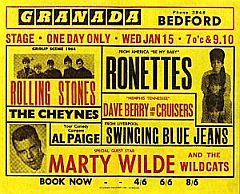

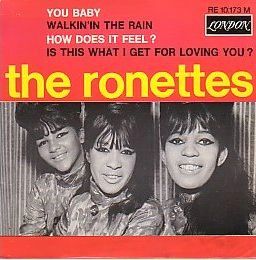

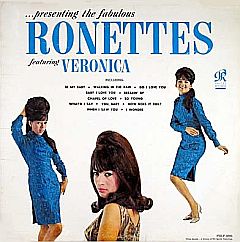

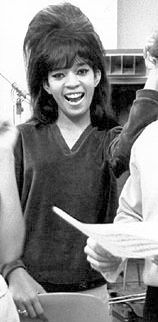

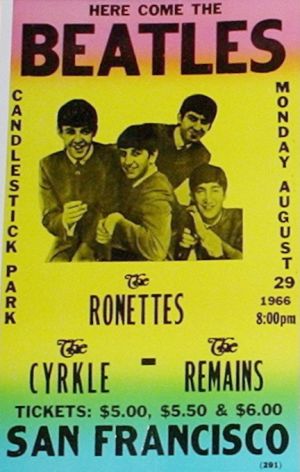

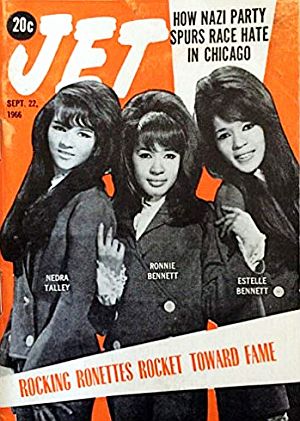

The Ronettes of the 1960s at the top of their game, circa 1963-64. Click on photo for separate story.

The Ronettes story is covered separately at this website in more detail — including song samples, the group’s biography, an account of Spector’s stormy relationship and marriage with lead singer Ronnie Bennett, and some later legal battles.

Music Player

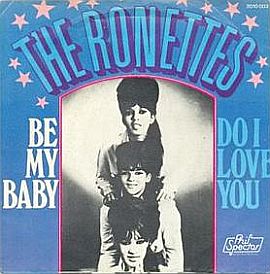

“Be My Baby”-1963

Suffice it to say here that the Ronettes were one of the key girl groups of the 1963-1964 period, turning out a series of hit songs that helped define that era, including “Be My Baby” of October 1963, one of the key genre-defining girl group songs.

|

“Spector-Made” “There’s No Other (Like My Baby)” |

Added to the National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress in 2006, “Be My Baby’s” description in that listing reads: “This single is often cited as the quintessence of the ‘girl group’ aesthetic of the early 1960s and is also one of the best examples of producer Phil Spector’s ‘wall of sound’ style. Opening with Hal Blaine’s infectious and much imitated drumbeat, distinctive features of the song, all carefully organized by Spector, include castanets, a horn section, strings and the able vocals of Veronica (Ronnie) Bennett. Enhancing the already symphonic quality of the recording is Spector’s signature use of reverb.”

Phil Spector, in any case, became a dominant girl group producer, churning out hit after hit with The Crystals, The Ronettes, Darlene Love, and others. He also worked with non-girl groups during the same period, including the Righteous Brothers, and a few years later, Tina Turner.

But from 1962 through 1964, Spector’s girl group sound was all over the charts. He produced at least 15 Top 40 girl group hits in those two years, some of which are listed in the table at right.

Spector worked with other songwriters on many of these hits. The Brill Building team of Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich, in particular, worked with Spector on a number of girl group hits. Among the songs they co-wrote with Spector were: “Da Doo Ron Ron” and “Then He Kissed Me” for the Crystals; “Be My Baby” and “Baby, I Love You” for the Ronettes; and also Darlene Love’s “(Today I Met) The Boy I’m Going To Marry.”

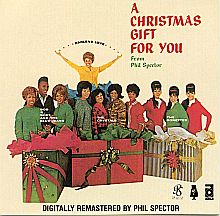

In addition, Spector also produced a Christmas album using the Ronettes, Darlene Love and others to record traditional Christmas favorites in the girl-group /wall-of-sound style – an album that is still popular to this day. Phil Spector the person, however, is quite another story, whose quirky and sometimes violent behavior has been widely written about elsewhere. In 2009, after two trials in Los Angeles, he was convicted of second-degree murder of actress Lana Clarkson and is presently serving a sentence of 19 years to life. But during his 1960s heyday, Spector had magical abilities in the recording studio.

Beyond the Phil Spector-produced girl group songs, there was additional activity in 1963 and 1964 with artists such as The Chiffons, Martha & The Vandellas, The Angels, The Jaynetts, and others. More on those groups in a moment. But first, some background on New York’s “Brill Building” writers and producers and their role in the girl group era.

|

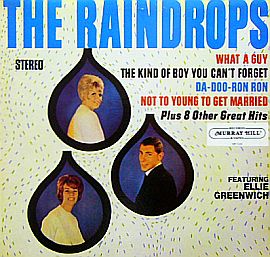

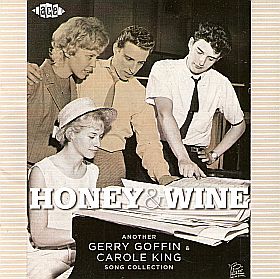

“Brill Building Pop”  Brill Building entrance in New York city at 1619 Broadway. By 1962, the Brill Building contained 165 music businesses of one kind or another. In fact, it became a place where the complete music making process – from song idea to finished record demo –could be completed in a manner of days. At the Brill Building, a song and melody could be written, musicians hired, demo cut, record companies and publishers contacted, managers and promoters hired. By the early 1960s, the “Brill Building method” of song making exploded with a frenzy of pop music production, as hits soared to the top of he music charts. In the process, some of the Brill Building writers, producers and publishers became quite wealthy.  Brill Building songwriter Carole King at piano, along with husband and composing partner Gerry Goffin, far right, on song collection CD cover with other songwriters.  Brill Building writers Barry Mann at the piano, with Cynthia Weil (left) and Carole King, 1965. Another songwriting team – Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil – also worked for Aldon Music and wrote a number of girl group hits, including: “I Love How You Love Me” for the Paris Sisters (#5, 1961); two for The Cyrstals, “He’s Sure The Boy I Love”(#11, 1962) and “Uptown”(#13, 1962); and “Walking In The Rain” for The Ronettes (#23, 1964 w/Phil Spector). Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich, another Brill Building team who also worked with producer Phil Spector, wrote several girl group hits, including two for the Crystals and one for Darlene Love described earlier. They also co-wrote several others with Spector including “Be My Baby” (#2, 1963) and “Baby I Love You”(#24, 1964) for The Ronettes, and “Chapel Of Love” for The Dixie Cups (#1, 1964). Barry and Greenwich also did two for the Shangri-Las – “Leader Of The Pack” (#1, 1964 w/Shadow Morton) and “Give Us Your Blessings”(#29, 1965). Sometimes the Brill Building writers would drift into releasing songs themselves. That happened in early 1963, when husband-and-wife team Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry recorded a demo titled “What a Guy,” a tune Barry had written for The Sensations. But Jubilee Records opted to have the Barry/Greenwich demo released as the single under the group name The Raindrops.As a result, “What A Guy” hit No. 41 on the Billboard chart. A follow-up, “The Kind of Boy You Can’t Forget,” did even better, reaching No. 17. The Raindrops sound was “girl-group” in style, with Greenwich singing lead with double-tracked harmony parts, and Barry providing bass vocals. Although they also released an album, the Barry/Greenwich excursion into recording as the Raindrops ended by 1965, around the time they became involved with writing songs for Red Bird Records. Red Bird was a record label owned by another songwriting team, Leiber & Stoller, along with George Goldner, a producer. Red Bird recorded hits such as the Dixie Cups’ “Chapel of Love” and the Shangri-Las’ “Leader of the Pack.” Don Kirshner’s Aldon Music also had a record label – Dimension – a label that produced girl-group and other hit songs.As for Brill Building writers moving into recording themselves, Carole King proved to be rising star on that front, later producing a long list of her own hit songs and albums – including the Grammy-winning and best-selling 1971 album, Tapestry. By 1965-1966, the talents of Brill Building writers and others like them were becoming less important as groups such as the Beatles, the Byrds, and the Beach Boys were setting the tone for other upcoming artists who wrote their own material. For some, the girl-group era ended with The Supremes’ song “You Can’t Hurry Love,” released in the summer of 1966. Don Kirshner’s Aldon Music, meanwhile, did quite well during the 1960s, making many millions, thanks in part to girl group hits. Between 1959 and 1966, Kirshner’s enterprise published some 500 songs, 400 of which had made the music charts. In April 1966, for example, he had 25 songs on the Billboard charts, including the reigning No. 1 song at the time by the Righteous Brothers, “You’re My Soul and Inspiration.” Kirshner’s songs by then had sold some 150 million recordings. Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, meanwhile, who had written some of Kirchner’s hit songs – including the Righteous Brothers No. 1 hit, “You’re My Soul and Inspiration” — had just signed a five-year $1 million contract with Kirshner that April 1966. Since Aldon Music by then had been sold to Columbia Pictures-Screen Gems, and Kirshner named v. p. of publishing and recording, the talents of writers like Mann and Weil would be turned more toward music for television and film. King and Goffin, for example, had a No. 3 hit for the TV group The Monkees with “Pleasant Valley Sunday” in 1967.Yet for a moment in time, the “Brill Building” methodology of churning out pop girl-group and other hits with teams of songwriters and producers, worked phenomenally well. |

The Chiffons girl group of the 1960s shown on a album cover featuring their greatest hits. Click for CD.

Music Player

“He’s So Fine”-1963

Their first hit, “He’s So Fine,” went to No.1 on the Billboard chart from March 30 – April 26, 1963. It sold over one million copies and is also known for its signature “doo-lang, doo-lang” refrain. The song was written by Ronald Mack and produced by The Tokens, who in 1961 had the No.1 hit, “The Lion Sleeps Tonight.”

In 1963-64, The Chiffons would put three other songs on the Top 40 list: “One Fine Day, which rose to No. 5 in the summer of 1963; “A Love So Fine,” which hit No. 40 in October 1963; and “I Have a Boyfriend,” which charted at No. 36 in January 1964.

Cover of CD for “Billboard Top Hits of 1963,” lists three popular “girl group” songs from that year. Click for CD.

Music Player

“One Fine Day”-1963

The year 1963 was among the most important and prolific years for the girl group sound, with hit after hit. Also in 1963, a young female singer from New Jersey, Lesley Gore, had a June No. 1 hit with “It’s My Party.” She followed that with three more Top Ten hits – “Judy’s Turn to Cry,” a No. 5 hit in July; “She’s a Fool,” another No. 5 hit in October; and “You Don’t Own Me,” a January 1964 No. 2 hit.

Lesley Gore’s “You Don’t Own Me” is viewed as one of the era’s more female-assertive tracks and also signaling a new direction. The Angels, also from New Jersey – Phyllis and Barbara Allbut and Peggy Santiglia – had No. 1 hit in August and September of 1963 with “My Boyfriend’s Back.”

The Jaynetts hit, "Sally Go Round The Roses," featuring French record jacket w/ anonymous model. Click for digital.

Music Player

“Sally Go Round The Roses”-1963

This song, arranged by Artie Butler, has a haunting, hypnotic quality for some listeners, due in part to studio production techniques utilizing reverb coupled with a layering of numerous female vocals. Reportedly, this song was also a performance favorite of Grace Slick prior to her Jefferson Airplane days and is also said to have been an influence on singer Laura Nyro.

Martha and the Vandellas on a 1964 record sleeve cover. Click on photo to visit their story at this website.

Music Player

“Heat Wave”-1963

Martha and her ladies scored three big hits in 1963 – “Come and Get These Memories,” a No. 29 hit in the spring; “Heat Wave,” a No. 3 hit in August; and “Quicksand,” a No. 8 hit in December. Martha & The Vandellas would turn out nine more Top 40 hits over the next three years – among them: “Dancing in the Street,” a No 2 hit in 1964; “Nowhere To Run,” a No. 8 hit in 1965; and “Jimmy Mack,” No. 10 in 1967. See “Motown’s Heat Wave” at this website for a separate story covering Martha and the Vandellas and their music. Also at Motown was female soloist, Mary Wells, regarded as one of Motown’s early 1960s superstars, who had several hits composed by Smokey Robinson, inlcuding: “You Beat Me to the Punch” (No. 9) and “Two Lovers” ( No. 7) in 1962, and her famous No. 1 hit of 1964, “My Guy.”

|

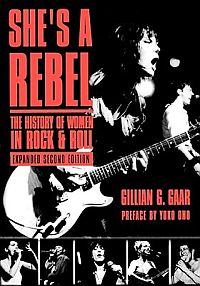

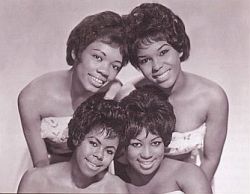

“Girl Group Woes” As buoyant and uplifting as girl group music may have been for millions of listeners, behind the scenes, in the production and management of that sound, there was a somewhat less happy scene unfolding. The girls themselves were often treated as pawns in the process. Though, to be sure, the top girl groups experienced elevated stardom and celebrity, traveled the world in some cases, and were certainly not deprived. Still, a number of the girl groups – especially those younger ladies in their teens and early twenties –“…I was fifteen years old. What do I know about conflict of interest and making a recording deal?” According to a conversation with Nona Hendryx of The Bluebells, as relayed in Gillian Gaar’s book, She’s A Rebel: “We would record songs, and listed on the [recording] as the writer would be his [the owner/producer’s] eight-month-old grandchild! It was just ridiculous. He owned the recording studio, he owned our contracts, we had his lawyers… I mean, talk about conflict of interest! But I didn’t know anything about conflict of interest. I was fifteen years old. What do I know about conflict of interest, and making a recording contract deal?” Hendryx also explained. “We got ripped off really badly over the years, especially from the Bluebells era… We ended up with nothing but our name – I don’t know who had the brains enough to ask for that at the time, but somehow we ended up with the name so we could work without any limitations. But we lost a lot of the money we were entitled to.”  When the Shirelles discovered in 1964 that their trust fund had evaporated, they went on strike. In 1963, The Shirelles learned that a trust holding their royalties – money they were supposed to receive from their Scepter Record label on their 21st birthday – did not exist. The money, they were told, had been spent on production, promotion and touring. The Shirelles went on strike and would not record. After a lawsuit and countersuit in the mid-1960s, an agreement was reached, but the damage had been done. The Shirelles believed they were lied to and deceived. In an interview some years later, Shirley Owens of the Shirelles would explain that their manager and record label owner, Florence Greenberg, had put on a “mother routine” which the girls had fallen for completely.  Some of Motown’s Marvelettes in happier times. The Shangri-Las were another short-changed girl group. As Gillian Garr reports in She’s A Rebel: “Despite their hits and frequent tours, the Shagri-Las saw little of the generated profits, which were eaten up in the black hole of management and studio costs.”  The Shangri-Las of the mid-1960s reportedly saw little of the profits from their hits. Click for CD. Phil Spector, for one, would be sued by at least three of the girl groups he worked with. The Crystals sued Spector for unpaid royalties, but lost their case, although they did salvage the rights to their group name, enabling them to continue working and use the name in performances. In 1993, Darlene Love sued Spector for back royalties, and a New York Supreme Court jury ruled in her favor in 1997, but because of the statute of limitations in New York State, awarded her $263,500 for royalties going back only to 1987. The Ronettes, who also sued Spector in later years, fared little better, and that case is covered in more detail in the “Be My Baby” story a this website. Girl group members who wrote their own songs sometimes had to fight for years to get their music publishing rights as song authors. Rosalie “Rosie” Hamlin of Rosie and The Originals, who wrote the No. 5 hit “Angel Baby” in 1960 at age 15, was not listed as the song’s author on the record label at the time it was a hit. Hamlin also found in her contract that she was ineligible to collect record royalties for the song because she was not listed as the songwriter. And although Hamlin did manage to obtain the copyright to her music in 1961, there were decades of battles that followed over royalties.Beyond the royalty wars and legal disadvantages the girl groups faced, there were also other issues, ranging from lack of media notice (female acts were not promoted or covered by the media and music press then as much as male artists, who in the industry’s words were “easier to sell”), to racism and sexism that were then much more prevalent. And due in part to the formula/production-line nature of song-making in those years, managers and producers did not always acknowledge the talents of their charges or treat them with professional respect in the recording process, sometime regarding them as interchangeable parts to be plugged into the pop music machine wherever they were needed. Still, despite the woes and difficulties girl groups faced in their careers, most were generally happy to have been a part of the process and to have had the professional help that made their careers possible – inadequate, short lived, and poorly compensated as some of those careers surely were. |

New Competition

Sheet music cover for The Toys’ 1965 hit song, “A Lovers Concerto,” Stateside Records. Click for CD.

From Los Angeles, Carol and Terry Fischer and Sally Gordon, 15 and 17 year-olds who comprised The Murmaids, had a No. 3 hit song with “Popsicles and Icicles” in January 1964. The Dixie Cups, three girls from New Orleans – sisters Barbara Ann and Rosa Lee Hawkins and their cousin, Joan Marie Johnson – recorded “Chapel of Love” for Red Bird Records in 1963. By early June 1964, the Greenwich/Barry/ Spector song had soared to No. 1, remaining there for three weeks and selling more than a million copies. The Dixie Cups would have three more Top-40 hits in 1964 and 1965.

The Toys, a girl group from Queens, NY, had a major No. 2 hit in October 1965 with “A Lover’s Concerto,” which was based on the melody of Johann Sebastian Bach’s classical piece, “Minuet in G major.” The Toys’ song – whose early lyrics include: “How gentle is the rain / That falls softly on the meadow / Birds high up in the trees / Serenade the flowers with their melodies” – was a million seller in 1965.

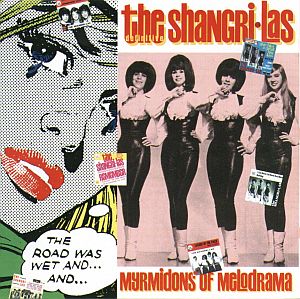

Cover of 1995 CD from RPM Records, U.K., “The Shangri-Las: Myrmidons of Melodrama,” which includes 33 of their tracks with annotation. Click for CD.

The Ronettes had started a change in look with their hairdos, tight skirts and Cleopatra style make-up. But in 1964, a Queens, New York group named The Shangri-Las took the look and sound in something of a new direction.

The Shangi-Las were a white group, formed in 1963 by two sets of sisters – Mary Weiss (lead singer) and Elizabeth “Betty” Weiss, and identical twins Marge and Mary Ann Ganser. The girls were still 15-to-17 years of age when their parents signed their contract with George “Shadow” Morton of the Red Bird record label in April 1964. They produced a series of songs that were mini-melodramas covering topics such as lost love, forbidden love (“Leader of the Pack”), teenage angst, and related themes that became quite popular in the U.S. and U.K..

1965: The Shangri-Las, in boots & leather, at radio station WHK, Geauga Lake Park, Cleveland, Ohio. Photo, George Shuba.

Music Player

“Remember…Walking in The Sand”-1964

Next, with the help of Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich at the Brill Building, Morton produced the Shangri-Las’ follow-up record, “Leader of the Pack,” which hit No.1 in the U.S. on November 28, 1964. It also hit No. 1 in Australia and No.11 in England. Although the group toured with other major rock acts and appeared on several TV shows, by 1966 their releases began to falter in the U.S., although they remained popular in England and Japan. They also influenced some 1970s punk rock-era acts such as the New York Dolls and Blondie, and later, the Go-Go’s. “Leader of the Pack” later recharted in the U.K in 1972 at No.3 and again in 1976 at No. 7, giving the Shangri-Las the distinction of being the only American vocal group to ever hit the upper reaches of the British Charts three times.

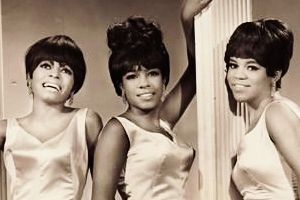

The Supremes in 1965: from left, Diana Ross, Mary Wilson, and Florence Ballard. Click for 'Definitive Collection' CD.

One girl group that emerged out of Detroit’s Motown music scene in the mid-1960s just as the Beatles and British invasion were coming on — and would go toe-to-toe with those groups on the music charts — was The Supremes.

In the late 1950s, the teenage threesome of Diana Ross, Mary Wilson, and Florence Ballard had formed their singing group while living in Detroit’s Brewster housing project. Initially they used another name during their high school years, but by January 1961, after signing with Berry Gordy’s Motown they changed their name at Gordy’s suggestion. They became “The Supremes,” a name credited to Florence Ballard. However, their first recordings at Motown – in fact, more than nine in a row – fell flat and went nowhere.

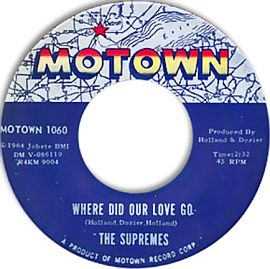

The Supremes’ first No. 1 hit, “Where Did Our Love Go,” sold more than 2 million copies. Click for CD.

Music Player

“Baby Love”-1964

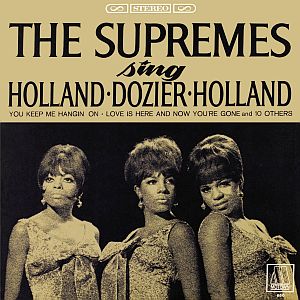

More top hits kept coming for the Supremes in 1965, 1966 and 1967. In fact between 1964 and 1967, the Supremes compiled one of the best all-time female recording track records in popular music history: releasing fifteen singles, all of which, except for one, made the Top Ten. In addition, ten of these songs were No. 1 hits. The Supremes’ success brought television exposure beyond what the other girl groups had received, as they appeared not only on teen shows such a Shindig and Hullabaloo, but also The Ed Sullivan Show and The Tonight Show. “Unlike other so-called girl groups,” observed The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll in 2001, “the Supremes had a mature, glamorous demeanor that appealed equally to teens and adults. Beautiful, musically versatile, and unique, the original Supremes were America’s sweethearts, setting standards and records that no group has yet equaled.” They also became important symbols of black success, and as The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia noted, “they were often seen at Democratic political fundraisers, for President Lyndon Johnson, among others…”

Album featuring Supremes singing hit songs composed by Motown’s Holland-Dozier-Holland team. Click for CD.

Music Player

“Come See About Me”-1964

H-D-H produced ten of The Supremes’ No. 1 singles, including: “Baby Love”, “Stop! In the Name of Love”, “You Keep Me Hangin’ On,” and the 1964 hit sampled above, “Come See About Me.”

The Supremes were nurtured by Gordy’s Motown organization, and like other groups there, they were put through the “Motown finishing school” receiving professional guidance in dance, etiquette, and fashion. However, some of the other Motown groups charged that the Supremes were given special attention by Berry Gordy, given the best songs, and helped along with more spending. And as was later learned, Gordy and Diana Ross had become involved in the mid-1960s.

The Supremes performing "My World Is Empty Without You" on “The Ed Sullivan Show” in 1966: Diana Ross (right), Mary Wilson (center), Florence Ballard (left). Click for 'Anthology' CD.

The Supremes — and Diana Ross later on her own — went on to separate careers, continuing to record and release songs beyond the 1970s, with reunion tours and some personnel changes in later years. Yet in terms of the classic 1960s’ girl group sound, The Supremes are often put in their own separate category, considered not typical of the teenage girl groups of that era, but rather, representing a somewhat more sophisticated and polished sound, with songs covering somewhat more adult themes. Still, the market reach of The Supremes for both teen and adult listeners was huge and stretched over several decades.

Other Girl Groups. Among groups and solo female artists not mentioned in this article that are sometimes included in girl group listings are: The Ad Libs, The Caravelles, Claudine Clark, Dee Dee Sharp, The Jelly Beans, The Pixies Three, Reparata and the Delrons, The Starlets, Mary Wells, and The Velvelettes. And beyond these, of course, there were hundreds of other girl groups that recorded during the 1960s, but for whatever reasons, did not achieve major notice.

Girl Group Legacy

The girl groups of the 1960s occupy something of unique niche in the history of rock `n roll music. They were singing groups that typically did not write their own songs nor play the musical instruments that powered those songs. Nor was the girl group sound a long-lasting genre. In fact, with the exception of The Supremes, it was a pretty compressed period; one that some historians mark as coming between Elvis Presley’s induction into the U.S. Army in 1958 and the Beatles’ rise in early 1964.

But that demarcation may be too simplistic, as “girl group music” of one form or another, as shown above, persisted well through the 1960s. And although the rise of the Beatles and the British invasion were factors, there was also something else: the way popular music began to be produced around that time. Groups such as the Beatles – but also extending to folk, surf, and solo female artists who began their rise in the mid-and late 1960s – were artists who wrote and performed their own songs. That was an important change in the means of production, as it fundamentally altered and outdated the Brill Building and Motown methodologies – the “assemblers” who had previously brought all the moving parts of pop song-making together. Girl group music also leaned on a formula of similar and repeating types of sound, song titles, and lyrics which could only be sustained for a few years before listeners yearned for something new. Still, the girl group sound made its mark and had its impacts. In some ways the era marked a unique coming together of voices, producers and writers – a once-in-a-great-while crossing of paths and talents that briefly produced some beautiful and lasting music.

As for the audience of that era, the verdict was clear and unequivocal: it was simply good music. The Boomer kids, growing up with the girl group sound, voted for it overwhelmingly with their dollars, sending the pop music business to a place it had never been before. And beyond those crazy kids, even a few serious music critics years later would extend their kudos.Greil Marcus, writing in 1992 for The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, then enthusing over some memorable moments from the girl group oeuvre, mentioned, among others: “…the piano on ‘One Fine Day’…the unbelievably sexual syncopation of the Shirelles’ ‘Tonight’s The Night’; the pile-driving force of ‘Da Doo Ron Ron’; the good smile of the Crystals’ ‘He’s Sure The Boy I Love’ – a smile that stretched all across America in 1963.” Marcus also added in his commentary:

…It was utopian stuff – a utopia of love between a boy and a girl, a utopia of feeling, of sentiment, of desire most of all. That the crassest conditions the recording industry has been able to contrive led to emotionally rich music is a good chapter in a thesis on Art and Capitalism, but it happened. That utopian spirit has stayed with those who partook of it – the formal style of girl-group rock has passed, but the aesthetic is there to hear in Bruce Springsteen, Patti Smith, Book of Love, Bette Miller….

And later, as historians dissecting the girl group era would acknowledge, there was something there worth saving. In the Library of Congress cultural preservation program, girl group songs are among those listed on the National Recording Registry, including, so far, The Ronettes’ “Be My Baby” and Martha & the Vandellas’ “Dancing in the Street.” There will, no doubt, be others to come. More common kudos for girl group music comes in other forms, too – the use of their songs by other artists being a prominent one. A number of girl groups songs have been covered by other artists, some of which have become hits themselves, but usually in most cases, bringing the music to new listeners.

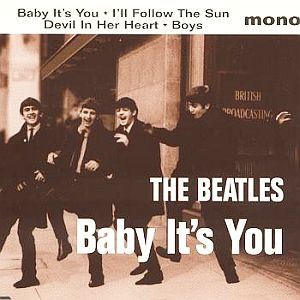

Cover photo of the Beatles on their March 1995 EP that included The Shirelles’ song, “Baby It’s You.” Click for CD.

Music Player

Mamas & Papas-“Dedicated To…”

Another Shirelles song, “Dedicated To The One I Love,” was given a boost by a 1967 cover version by The Mamas & The Papas with Michelle Phillips on lead. This version (above) went to No. 2 in both the US and UK.

The group Smith in 1969 and The Carpenters in 1970-71 also released versions of The Shirelles’ song “Baby It’s You.” More than 20 other artists have also recorded the song. Similarly, The Shirelles’ “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” has been recorded by a long list of artists – from The Chiffons in 1963 and song co-author Carole King on her 1971 Tapestry album, to Amy Winehouse who recorded a slowed-down, jazzy version for the 2004 film Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason.

Record jacket for April 1967 Beach Boys single, “Then I Kissed Her” cover of Crystals song. Click for digital.

Two years later, in April 1967, the Beach Boys released the song as a single in the UK where it charted at No. 4.

Singing duo Sonny & Cher also covered “And Then He Kissed Me,” issued on a French four-song EP in 1965.

And Bruce Springsteen covered the song in some of his live performances in 1975 under the title, “Then She Kissed Me.” He also used the same song in more recent years, opening a concert with it in August 2008 in St. Louis, and performing it by request in Sunrise, Florida during a September 2009 encore performance.

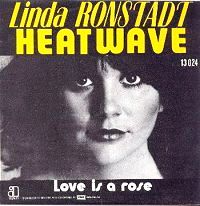

“(Love is Like a) Heat Wave,” the 1963 hit song by Motown’s Martha and the Vandellas, has some interesting cover history as well. Linda Ronstadt had a No. 5 hit with the song in November 1975, and Phil Collins released a single version of “Heat Wave” in September 2010.

The Lovin’ Spoonful’s John Sebastian revealed in 2007 how he sped up the three-chord intro from “(Love Is Like a) Heat Wave” to come up with the intro for the Spoonful’s 1965 hit, “Do You Believe in Magic.”

And in recent years, the song has been used by at least five contestants on the American Idol TV show.

Many other 1960s’ girl group songs have similar histories of cover-version recordings; only a sampling has been offered here.

Film & TV Music

The 1996 film, “One Fine Day,” used The Chiffons’s popular 1963 song of that name in the film score. Click for film DVD.

Martha & the Vandellas’ song “Heat Wave” was sung by Whoopi Goldberg in the 1992 film Sister Act, and also featured in Backdraft of 1991 and More American Graffiti of 1979. “A Lover’s Concerto” by The Toys was used in the 1995 film Mr. Holland’s Opus, and “One Fine Day” by the Chiffons was used in the 1996 film by that name starring Michelle Pfeiffer and George Clooney. The Ronettes’ “Baby I Love You” is part of the soundtrack for the 1995 Hugh Grant-Julianne Moore film Nine Months, and the soundtrack for the 1999 film A Walk on the Moon featured a remake of the Jaynetts song, “Sally Go ‘Round the Roses.” And this is only a partial list.

Girl Group Books

Among books that cover or include 1960s’ girl groups as a subject are, for example: Alan Betrock’s 1982 book, Girl Groups: The Story of a Sound; Gillian Gaar’s 1992 book, She’s a Rebel: The History of Women in Rock & Roll; John Clemente’s 2000 book, Girl Groups: Fabulous Females That Rocked the World; and Jacqueline Warwick’s 2007 book, Girl Groups, Girl Culture. Laurie Stras, a senior lecturer in music at the University of Southampton in the U.K. has edited a 2011 anthology that explores 1960s girl singers and girl groups in the U.S. and the U.K. – She’s So Fine: Reflections on Whiteness, Femininity, Adolescence and Class in 1960s Music. Academic and trade journal articles have also delved into various aspects of the 1960s girl-group era, a few of which are listed below in “Sources.”

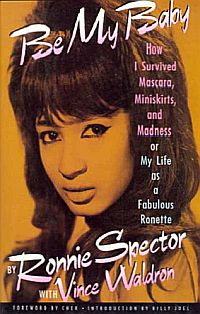

Girl group members themselves have taken up the pen to tell their own stories of their years in the music business, some of them turbulent tales. Among these books have been, for example: Mary Wilson’s 1986 book, Dreamgirl: My Life As a Supreme, written with Patricia Romanowski and Ahrgus Juilliard; Ronnie Spector’s 1990 book, Be My Baby: How I Survived Mascara, Miniskirts, and Madness, or My Life As a Fabulous Ronette; Martha Reeves 1994 autobiography with Mark Bego, Dancing in the Street: Confessions of a Pop Diva; and Darlene Love’s 1998 autobiography, My Name Is Love.

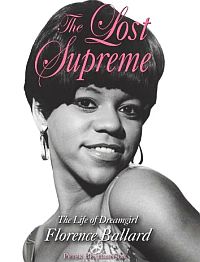

Added to these are girl group books written by outside authors, such as: Marc Taylor’s 2004 book, The Original Marvelettes: Motown’s Mystery Girl Group; J. Randy Taraborrelli’s 2007 biography, Diana Ross; and Peter Benjaminson’s 2008 book, The Lost Supreme: The Life of Dreamgirl Florence Ballard. There have also been several books written about Phil Spector’s life and work, among them, Mark Ribowsky’s 1989 book, He’s a Rebel: The Truth About Phil Spector – Rock and Roll’s Legendary Madman, and Mick Brown’s 2007 book, Tearing Down the Wall of Sound: The Rise and Fall of Phil Spector.In 2005, Ken Emerson wrote a book about the Brill Building scene – Always Magic in the Air: The Bomp and Brilliance of the Brill Building Era. Former Brill Building songwriter and singer Carole King has written a 2012 memoir titled, A Natural Woman.

A number of books have also covered Motown’s history, including Berry Gordy’s 1994 autobiography, To Be Loved: The Music, the Magic, the Memories of Motown, and Peter Benjaminson’s 2012 book, Mary Wells: The Tumultuous Life of Motown’s First Superstar.

Stage & Screen

On Broadway and in Hollywood, girl group stories have been told, and more are in development. Perhaps the most famous of the stage productions so far has been Dreamgirls, a 1981 Broadway musical based in part on the rise of performers such as The Supremes, The Shirelles, James Brown, Jackie Wilson, and others. In the play, a young female singing trio from Chicago named “The Dreams” become music superstars. The musical was nominated for thirteen Tony Awards and won six. Dreamgirls was also made into a successful Hollywood film in 2006, starring Jamie Foxx, Beyoncé Knowles, Eddie Murphy, Jennifer Hudson, Danny Glover, and others. The film won three Golden Globes and two Oscars.

In April 2011, Baby It’s You!, another musical with girl group roots, debuted on Broadway. This production featured the music of The Shirelles and offered the story of their manager, Florence Greenberg and her Scepter Records, the recording label Greenberg started when she signed The Shirelles. This production ran for 148 performances, opening at the Broadhurst Theater in April 2011 and closing that year in September.

Years earlier, in 1985, a Broadway show titled Leader of the Pack, dedicated to songs co-written by Brill Building songwriter Ellie Greenwich and based on her life, also ran on Broadway where it was nominated for a Best Musical Tony.

2013 playbill from the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre for the Broadway show, “Motown The Musical.” Click for song originals.

For The Ages

So, the upbeat and joyful music of the 1960s’ girl-groups lives on – in various forms and venues – staying alive for the future. But for some who lived through that time and actually experienced the music making in those years, there’s no substitute for the real thing. LaLa Brooks who sang lead on several of The Crystals big hits in the 1960s, gave an October 2011 interview with Mindy Peterman of the Morton Report during which she reminisced about working in the studio with Phil Spector and the parade of live musicians and singers who came together back then to produce the songs. Similar scenes were common at Motown and the Brill Building. That era is gone now, and those recording sessions can never be repeated, but Brooks is sure that the sound they made back then was special and unique, and she was glad to have been a part of it:

“…I remember there were so many people in the studio. That was fascinating. Just to sit outside the studio in the seating area before I put on the vocals and seeing all the musicians just playing live, which they don’t do today. I think that was an experience. So many of the young artists now, they’re using all kinds of computers and some kind of technology. They lose that gift that I had in the studio with Phil [Spector] with all the musicians at one time playing.”

Three CD collection from The Marvelettes (2009), showing from top left: Gladys Horton, Katherine Anderson, Georgeanna Tillman, and Wanda Young. Click for CD.

Music Player

The Marvelettes-“Forever”

(Wanda Young, lead)

And as more distance is put between that time and those songs, it does appear that the era, and the music made then, will stand out in a good way. And however accidental, serendipitous, and/or opportunistic that music-making may have been in its day, the “girl group sound” remains a gift for the ages.

For other stories at this website on the history of popular music please visit the Annals of Music category page or go to the Home Page for additional story choices. See also, “Noteworthy Ladies,” a topics page with 40 more story choices about famous women. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support this website. Thank you. — Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 25 June 2013

Last Update: 16 July 2023

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “1960s Girl Groups:1958-1966,”

PopHistoryDig.com, June 25, 2013.

____________________________________

Books at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

|

“Girl Group Hits” The Shirelles |

Greil Marcus, “The Girl Groups,” in Anthony De Curtis and James Henke (eds), The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, Random House, New York, 1992, pp. 189-190.

“Girl Groups: A Short History,” History of Rock.com.

Alan Betrock, Girl Groups: The Story of a Sound, Delilah Books / Putnam Publishing Group, 1982, 516 pp.

“100 Greatest Girl Group Songs,” DigitalDream Door.com.

“Girl Group,”Wikipedia.org.

Frank Hoffmann with Robert Birkline, “Girl Groups,” Survey of American Popular Music (website), Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, Texas.

Bob Hyde and Walter DeVenne, “Maybe, The Chantels,” The Doo Wop Box, Booklet & Liner Notes (used in PBS promotions), Rhino Records, 1993, pp. 56-57.

Jacqueline Warwick, Girl Groups, Girl Culture, new edition, Routledge, 2007, paperback, 288 pp.

“The Shirelles,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, Rolling Stone Press, New York, 3rd Edition, 2001, pp. 880-881.

“The Shirelles,” Wikipedia.org.

Bill Janovitz, Song Review, “Will You Love Me Tomorrow?,” AllMusic.com.

Joel Whitburn, The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits, New York: Billboard Books, 8th Edition, 2004.

Ian Dove, “The Shirelles Sing ‘Soldier Boy’ In a Rock Revival at the Garden,” New York Times, December 31, 1972.

Amy Ellis Nutt, “Passaic Dedicates Street to the Ones it Loves: The Shirelles,”The Star-Ledger (Newark, NJ), September 22, 2008.

“The Marvelettes,” Wikipedia.org.

“The Marvelettes,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, Rolling Stone Press, New York, 3rd Edition, 2001, pp. 614-615.

Joe McEwen and Jim Miller, “Motown,” in Anthony De Curtis and James Henke (eds), The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, Random House, New York, 1992, pp. 277-292.

“Locking Up My Heart” (Marvelettes song), Wikipedia.org.

Marc Taylor, The Original Marvelettes: Motown’s Mystery Girl Group, Aloiv Publishing Co.,, 2004, 219 pp.

Andy Greene, “Gladys Horton of the Marvelettes Dies at 66; Horton Sang Lead on ‘Please Mr. Postman’ and ‘Too Many Fish in the Sea’,” RollingStone.com, January 27, 2011.

“The Paris Sisters,”Wikipedia.org.

“The Exciters,” Wikipedia,org.

“The Cookies,” Wikipedia.org.

Bruce Eder, “The Cookies, Biography,” AllMusic .com.

“The Orlons,” Wikipedia.org.

“The Crystals,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, Rolling Stone Press, New York, 3rd Edition, 2001, p. 229.

“He’s A Rebel,” Wikipedia.org.

Nick Cohn, “Phil Spector,” in Anthony De Curtis and James Henke (eds), The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, Random House, New York, 1992, pp.177-188.

“Phil Spector/The Teddy Bears,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, Rolling Stone Press, New York, 3rd Edition, 2001, pp. 922-923.

Jack Doyle, “To Know, Know…Him, 1958-2010” (includes Teddy Bears & Phil Spector history), PopHistoryDig.com, December 19, 2010.

“Phil Spector, Biography,” RollingStone.com.

Mark Ribowsky, He’s a Rebel: Phil Spector, Rock and Roll’s Legendary Producer, New York: Perseus, 2007.

“Phil Spector,” Times Topics, The New York Times.

Dave Thompson, Phil Spector: Wall Of Pain, (updated paperback edition), Omnibus Press, March 1, 2010.

“The Crystals,” Wikipedia.org.

“Then He Kissed Me,” Wikipedia.org.

“Da Doo Ron Ron,” Wikipedia.org.

Frank Hoffmann with Robert Birkline, “The Spector Sound,” Survey of American Popular Music (website), Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, Texas.

“Wall of Sound,” Wikipedia.org.

Jack Doyle, “Be My Baby: 1960s-2010” (The Ronettes history), PopHistoryDig.com, January 18, 2010.

Greg Shaw, “Brill Building Pop,” in Anthony De Curtis and James Henke (eds), The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, Random House, New York, 1992, pp.

Bruce Pollock, When Rock Was Young, New York: Holt, Reinhardt & Winston, 1981.

“Man With the Golden Ear,” Time, Friday, April 22, 1966.

“Don Kirshner and Aldon Music,” History of Rock.com.

“Spotlight on Brooks Arthur!,” Artie Wayne On The Web, October 12, 2011.

“The Chiffons,” Wikipedia.org.

“The Chiffons,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, Rolling Stone Press, New York, 3rd Edition, 2001, pp. 174-175.

“The Jaynetts,” Wikipedia.org.

“Sally Go ‘Round the Roses,” Wikipedia.org.

“Martha and the Vandellas/Martha Reeves,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, Rolling Stone Press, New York, 3rd Edition, 2001, pp. 613-614.

“(Love Is Like a) Heat Wave,” Wikipedia.org.

Jack Doyle, “Motown’s Heat Wave: 1963-1966″( Martha & the Vandellas), PopHistory Dig.com, November 7, 2009.

Gillian Gaar, She’s a Rebel: The History of Women in Rock & Roll, Seattle: Seal Press, 1992. 488 pp.

Robert McG. Thomas, Jr., “Florence Greenberg, 82, Pop-Record Producer,” New York Times, November 4, 1995.

Ann Powers, “Doris Kenner-Jackson, 58, Singer In the Original Shirelles Foursome,” New York Times, February 8, 2000.

Sharon Krum, Scripps Howard News Service, “1960s Girl Groups Are Getting Their Own Back,” Star-News (Wilmington, NC), July 29, 1998.

“The Dixie Cups,”Wikipedia.org.

“The Dixie Cups,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, Rolling Stone Press, New York, 3rd Edition, 2001, p. 268.

Robert F. Worth, “A Sad Song for the Ronettes: Court Reverses Royalty Rights,” New York Times, October 18, 2002, p. B-3.

“Ronettes Denied Song Royalties,” Los Angeles Times, October 19, 2002, p. E-2.

John Caher, “Ronettes’ Profits Limited by 1963 Contract,” New York Law Journal, October 21,2002.

Cynthia J. Cyrus, “Selling an Image: Girl Groups of the 1960s,” Popular Music, Vol. 22, No. 2, Cambridge University Press, May, 2003, pp. 173-193.

Reebee Garofalo, Chapter 6, “Popular Music and Political Culture: The Sixties,” Rockin Out: Popular Music in The U.S.A, Pearson, 2012.

“The Murmaids,” Wikipedia.org.

“The Toys,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, Rolling Stone Press, New York, 3rd Edition, 2001, pp. 1,000-1,001.

Katy June-Friesen, “The Real Dreamgirls: How Girl Groups Changed American Music,” Smithsonian.com, February 1, 2007.

“The Shangri-Las,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, Rolling Stone Press, New York, 3rd Edition, 2001, p. 876.

“The Supremes/Diana Ross & the Supremes,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, Rolling Stone Press, New York, 3rd Edition, 2001, pp. 960-963.

“Rock ‘n’ Roll: The Sound of the Sixties,” Time, Friday, May 21, 1965.

Richard Williams, “Sweet Nothings; The Lyrics Are All about Boyfriends, the Melodies Only a Few Bars Long. Why Are the 1960s Girl Groups Still So Enchanting?,” The Guardian, Friday, January 20, 2006.

Laurie Stras (ed), University of Southampton, UK, She’s So Fine: Reflections on Whiteness, Femininity, Adolescence and Class in 1960s Music, Ashgate, September 2011, 284 pp.

“Baby It’s You!” (stage production), Wikipe-dia.org.

“Dreamgirl: My Life As a Supreme,” Wikipe-dia.org.

“Dreamgirls (musical),” Wikipedia.org.

“Dreamgirls (film),” Wikipedia.org.

Daniel Kreps, “‘Be My Baby’ Songwriter Ellie Greenwich Dead at 68,” RollingStone.com, August 26, 2009.

Allan Kozinn, Arts Beat Blog, “A Carole King Musical Is Broadway Bound,” New York Times, March 15, 2013.

Mindy Peterman,”‘Da Doo Ron Ron’! An Interview with La La Brooks, Original Lead Singer of The Crystals,” TheMorton Report.com, October 8, 2011.

Gerri Hirshey, We Gotta Get Out of This Place: The True, Tough Story of Women in Rock, June 2002, 304 pp.

Melissa Block, ” ‘One Kiss:’ A Box Full of Girl Groups,” NPR, December 15, 2005.

Brittany Beyer, “Women Who Rock: Early 1960s and Girl Groups,”Broad Strokes, October 11, 2012.

“The Girl Groups,” History of Rock.com.

Victor Brooks, Last Season of Innocence: The Teen Experience in the 1960s (hardback), Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, April 2012, 216 pp.

______________________________