1940s: A young Frank Sinatra in a CBS studio.

In the early 1940s, as radio and recordings were making singers more broadly popular, it became clear they could also draw huge, adoring crowds to their live performances. And one of the first modern “teen idols” to do just that was a young singer from Hoboken, New Jersey named Frank Sinatra.

Sinatra had begun to make his mark on the music world in 1939 with big band leader Harry James, and then in 1940-42 with Tommy Dorsey. In July 1940, he had his first No. 1 hit with “I’ll Never Smile Again.”

By 1942, as Sinatra’s music was broadcast on the live radio show, Your Hit Parade, sponsored by Lucky Strike cigarettes, the young singer began attracting the attention of teenage girls. The “Bobby-soxers,” as they were called for their rolled-to-the-ankle white socks, were soon swooning in the aisles for young “Frankie.”

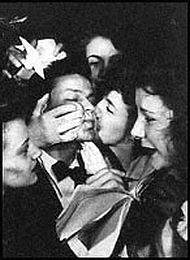

New York fans mob Sinatra, 1943.

At The Paramount

On December 30,1942, when Sinatra played his first solo concert at New York city’s Paramount Theater near Times Square, the Bobby-soxers came out in droves. After being introduced by Jack Benny, Sinatra walked on stage to loud and continuous shrieks and screams. “The sound that greeted me,” he later recalled, “was absolutely deafening. It was a tremendous roar. Five thousand kids, stamping, yelling, screaming, applauding. I was scared stiff. I couldn’t move a muscle. [Band leader] Benny Goodman froze, too. He was so scared he turned around, looked at the audience and said, ‘What the hell is that?’ I burst out laughing.” The kids screamed in delight; some even fainted. They also crowded the back stage door after the show shrieking for his autograph, and spilled over into Times Square, snarling traffic. Sinatra by then had become a recording sensation. He was so popular at the Paramount, that his engagement there was extended to February 1943. He played the Paramount for nearly four solid weeks, first with Goodman and then an orchestra led by Johnny Long“Not since the days of . . . Valentino has American womanhood made such unabashed public love to an entertainer.” –Time, 1943. But Sinatra’s drawing power was real, and so was his talent. Between 1940 and early 1943 he had 23 top ten singles on the new Billboard music chart. And all through those years, back at Paramount and other venues, the kids continued screaming and swooning for Sinatra.

“In various manifestations, this sort of thing has been going on all over America the last few months,” wrote one Time reporter who had observed Sinatra’s screaming kids at a July 1943 Paramount performance. “Not since the days of Rudolph Valentino has American womanhood made such unabashed public love to an entertainer.” Fans had not swooned or screamed over other singers, such as Bing Crosby. So what was it with Sinatra? Something else was going on, the critics surmised. Although his singing was certainly a factor, some charged it was also Sinatra’s look; his seeming innocence, frailty, and vulnerability that evoked the passions of female fans. Newsweek magazine then viewed the Bobby-soxer phenomenon as a kind of madness; a mass sexual delirium. Some even called the girls immoral or juvenile delinquents. But most simply saw them as young girls letting their emotions fly. Still, Sinatra fan clubs were cropping up all over America, and not just among teenagers; 40 year-old women were enlisting too.

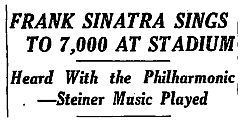

New York Times story of August 3,1943 on Sinatra appearance with the New York Philarmonic for a night of pop singing at Lewisohn Stadium at City College.

Frank Sinatra being greeted by fans at Pasadena, CA train station, August 1943.

Dubbed “The Columbus Day Riot,” the police were called in to diffuse the situation. Part of the problem had to do with fans who refused to leave the theater after having seen one complete show. Repeat performances were then being scheduled in tight rotation, running nearly all day and into the night.

In theaters with a capacity for 3,000 to 3,500 fans, sometimes as few as 250 would leave at the show’s end. Some were known to sit through dozens of performances to the point of becoming faint, remaining in their seats for six or eight hours without food and refusing to leave until forcibly removed by attendants.

Frank Sinatra fans waiting on line, Pittsburgh, PA, December 11th, 1943.

“[H]e is smart enough to know,” wrote Time magazine about his fan base in July 1943, “that if he is lucky they will be his adult public ten years from now, [and] will buy the cereals, cigarettes, radios, cars which he hopes to sell.”

In the fall of 1944, Sinatra’s fame brought him into his first round of “up-close-and-personal” politics, meeting with President Franklin Roosevelt in September. Sinatra publicly supported the president’s re-election bid that October.

In New York city, Sinatra’s young fans came out in some numbers to hear a late October speech he made on behalf of Roosevelt at Carnegie Hall. Sinatra also campaigned for Roosevelt in November 1944.

Frank Sinatra by then had also entered the business world, setting up a music publishing business. But out on the concert circuit, and in the sale of his recordings, Sinatra’s singing continued to enthrall millions of teenagers and young adults.

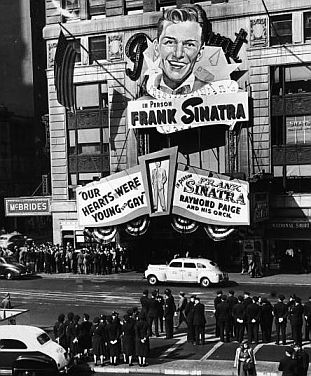

Frank Sinatra giant marquee at New York's Paramount Theater, October 1944. (photo - Hulton Archive/Getty Images).

“. . . The United States is now in the midst of one of those remarkable phenomena of mass hysteria which occur from time to time on this side of the Atlantic. Mr. Frank Sinatra, an amiable young singer of popular songs, is inspiring extraordinary personal devotion on the part of many thousands of young people, and particularly young girls between the ages of, say, twelve and eighteen.

The adulation bestowed upon him is similar to that lavished upon Colonel Lindbergh fifteen years ago, Rudolph Valentino a few years earlier, or Admiral Dewey, the hero of Manila Bay, at the turn of the century.Mr. Sinatra has to be guarded by police whenever he appears in public. Indeed, during the late political campaign he broke up a demonstration for Governor Dewey, the Republican candidate, merely by presenting himself on the sidelines as a spectator. . . .

Frank Sinatra, 1943 Life magazine photo.

. . .It is reasonable to suppose that his popularity with young people was at first a fiction invented by his press agent; it is not uncommon for myths of this sort to be set going by those enterprising gentlemen, and young people have even been hired to riot on a small scale in a music-hall or cinema to demonstrate the popularity of a performer. There is no doubt, however, that the matter has now become a genuine phenomenon . . .”

By 1946 Frank Sinatra’s recording company, Columbia, estimated that he was selling 10 million records per year. Yet these were still the early years for Frank Sinatra. He had another 40-plus years of performing and music-making ahead.

Other stories at this website with Frank Sinatra content include: “Ava Gardner, 1940s-1950s” (see “Ava & Frank” sidebar on their relationship); “Mia’s Metamorphoses, 1966-2010” (Frank Sinatra / Mia Farrow marriage & divorce); “The Jack Pack, Pt. 1, 1958-1960,”(Sinatra’s Rat Pack help for JFK’s presidential run in 1960); and “The Jack Pack, Pt. 2, 1961-2008″ (Sinatra falling out with Kennedys, post election; Sinatra & Reagan, etc.); and, “Sinatra: Cycles, 1968,” profiles a classic Frank Sinatra song. Additional celebrity history can be found at the Celebrity & Icons page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

________________________

|

Please Support Thank You |

Date Posted: 18 March 2008

Last Update: 21 August 2016

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “The Sinatra Riots, 1942-1944,”

PopHistoryDig.com, March 18, 2008.

_____________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“That Old Sweet Song,” Time, Monday, July 5, 1943.

“Symphonic Sinatra,” Time, Monday, August 23, 1943.

“Frank Sinatra Sings to 7,000 at Stadium; Heard With the Philharmonic – Steiner Music Played,” New York Times, Wednesday, August 4, 1943, p. 14.

“Sinatra Fans Pose Two Police Problems And Not the Less Serious Involves Truancy,” New York Times, October 13, 1944.

“Youngsters Flock to Sinatra Speech; Overflow Crowd Hears Singer Urge Roosevelt Re-election at Carnegie Hall,” New York Times, Wednesday, October 25, 1944, p. 16.

“Frank Sinatra and The ‘Bobby-Soxers’,” Guardian Unlimited (London), New York correspondent, Wednesday, January 10, 1945.

“The Life of Frank Sinatra, Part 2,” Originally written and compiled by Gary Cadwallader for Seaside Music Theatre and MaryAnn Eifert for research materials, posted at Summer Wind Productions.com, March 2008.

“Frank Sinatra” and “1943 in Music,” at Wikipedia.org.

Antony Summers and Robbyn Swan, Sinatra: The Life, New York: Doubleday, 2005.

____________________________