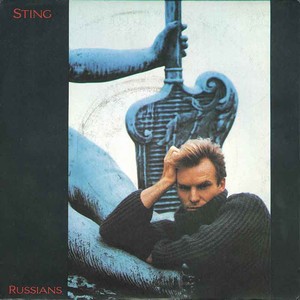

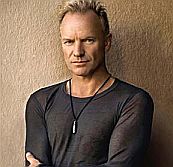

Formerly a member of the rock group Police, Sting had embarked on a new phase in his career. His debut solo album, The Dream of the Blue Turtles, released in June 1985, included a song entitled “Russians,” which was also released as a single in November that year.

Music Player

Sting: “Russians”

[scroll down for lyrics]

Ronald Reagan was President of the United States at the time, and Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister of the U.K. In the Soviet Union, a succession of three leaders had occurred in the early- to mid-1980s: Yuri Andropov, Konstantin Chernenko, and Mikhail Gorbachev. The nuclear arsenals of the two “superpowers” — as the U.S. and the Soviet Union were then called — were still aimed at each other.

Sting’s song was leveled at both sides, drawing on the Cold War’s nuclear rhetoric, which by the early- and mid-1980s was running quite hot between the U.S. and Russia, with Europe caught in the middle. Sting set his lyrics to the dirge-like Russian music of Sergei Prokofiev’s Lieutenant Kije Suite. His song covers some Cold War history, the bomb’s origins, and the tough talk that began in the 1950s.

“Mr. Khrushchev Says…”

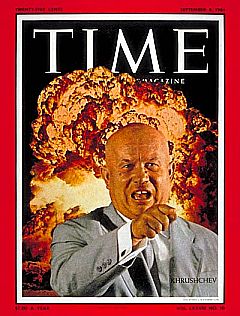

Nikita Khrushchev, 1950s.

Sting first points to the famous November 1956 line by Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev, who said, generally translated, “we will bury you” meaning the capitalist West. Khrushchev was addressing Western ambassadors at a Polish embassy reception in Moscow on November 18, 1956 when he made the remarks.

Time magazine about a week later reported on Khrushchev’s speech, noting that he said, in part: “…Whether you like it or not, history is on our side. We will bury you!”

There were some differences over the exact translation of Khrushchev’s words, interpreted by some as “we will dig you in,” or to mean “we will attend your funeral.”

Khrushchev on the cover of Time magazine early September 1961 when the Soviets resumed nuclear testing.

“I once said, ‘We will bury you,’ and I got into trouble with it. Of course we will not bury you with a shovel. Your own working class will bury you.” Khrushchev was here referring to the Marxist proletariat as “the undertaker of capitalism” with communism the ultimate victor.

In any case, “we will bury you” is what stuck and became a famous line from the mid-1950s on. Everyone knew the threat and implication. Republican U.S. Senator Barry Goldwater, when he ran for president in 1964, used a clip of Khrushchev making the remark during his presidential campaign. Khrushchev came off as a gruff and hostile leader in his speeches, prone to expressive outbursts.

In an October 1960 speech at the United Nations (photo above), he reportedly pounded his shoe on the rostrum for effect. His unpredictable and blunt style, made him even more menacing in Western eyes. In any case, he was one of those Russian leaders who augured the Cold War ideology deeply into the world’s psyche in those years, which is why, no doubt, Sting chose to use him in the song.

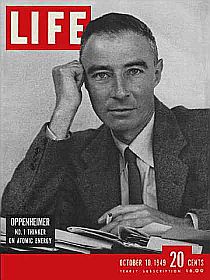

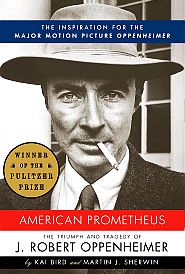

“Oppenheimer’s Deadly Toy…”

Sting also touches on the origins of the bomb, with the line: “how can I save my little boy from Oppenheimer’s deadly toy.” Oppenheimer here is J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904- 1967), the American theoretical physicist and University of California, Berkeley physics professor who is known as “The Father of the Atomic Bomb.” He was the scientific director of the Manhattan Project: the World War II effort to develop the first nuclear weapons at the secret Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. Much has been written about Oppenheimer’s changing views on the value of nuclear weapons, first believing they would end all wars, then in later years trying to put the genie back in the bottle.

Oppenheimer explaining the atomic bomb to U.S. military leaders, 1946.

The bomb that Oppenheimer and his team developed was used on Japan during WWII, dropped on two cities in August 1945 — Hiroshima and Nagasaki — touching off for decades thereafter, an escalating nuclear arms contest between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The understanding that followed with the nuclear arms build-up in both the U.S. and Soviet Union was that any nuclear exchange between the superpowers would result in all-out war and “Mutually Assured Destruction” (MAD).

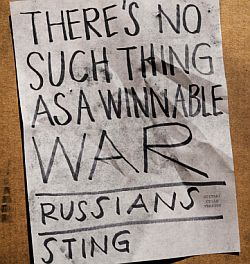

“Winnable War”

In 1981, as the Administration of U.S. President Ronald Reagan assumed power in Washington, there began some tough and loose talk about the use of nuclear weapons. Reagan himself remarked at one point, for example, “Yes, there could be a limited nuclear war in Europe.” “The probability of nucle- ar war is 40 percent …and our strategy is winnable nuclear war.”

-Richard Pipes, 1982 And Secretary of State Alexander Haig in 1981 also said: “We have contingency plans to fire a [nuclear] warning shot at the Soviet Union, warning of U.S. intentions to begin a nuclear war.” By late 1981, as reported by the New York Times, President Reagan approved a National Security Decision Document committing the United States to fight and win a global nuclear war. And some of Reagan’s top advisors at the time were quite clear on their positions. “There is no alternative to war with the Soviet Union if the Russians do not abandon communism,” said Richard Pipes, a top Reagan adviser in 1981. And Pipes again in 1982: “The probability of nuclear war is 40 percent…and our strategy is winnable nuclear war.” This, no doubt, is what Sting is singing about in the next verse of his song:

“There is no historical precedent,

To put the words in the mouth of the president

There’s no such thing as a winnable war

It’s a lie that we don’t believe anymore…”

“We Will Protect You…”

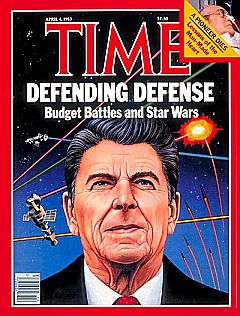

Next came Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), also known as “Star Wars,” a take-off on the popular 1977 film of that name by George Lucas. Reagan gave his “Star Wars” speech on March 23, 1983, proposing a space-based defense system equipped with high-powered lasers that would shoot down incoming Soviet missiles.

Only a few weeks earlier, on March 8, 1983, Reagan had given his “Evil Empire” speech, in which he pointedly meant the Soviet Union. In an earlier speech to the British House of Commons on June 8, 1982, although he did not use the exact phrase “evil empire,” Reagan had sounded similar anti-Soviet themes, outlining the evils of totalitarianism.

All of this rhetoric was needed, in part, to justify the new nuclear defense hardware Reagan was proposing. But the “Star Wars” plan brought protests from Congress, Europe, and elsewhere, and was also charged with violating other international measures to prohibit the militarization of space. Still, the Reagan Administration charged ahead with money and planning as the U.S. Defense Department began to work on the new program. But Sting, in his song, wasn’t buying the idea of protection.

|

“Russians” In Europe and America Mr. Khrushchev said we will bury you How can I save my little boy We share the same biology There is no historical precedent Mr. Reagan says we will protect you We share the same biology |

“…The Same Biology”

In his song, Sting’s plea is for common sense. “We share the same biology, regardless of ideology,” he says in one of the lines, asking more or less, why do we want to kill one another; what’s the sense in that? His hope: “that the Russians love their children too.”

In a later interview in 1994, Sting gave some of the background on this song and how it came about:

“Russians” is a song that’s easy to mock, a very earnest song, but at the time it was written — at the height of the Reagan-Rambo paranoia years, when Russians were thought of as grey sub-human automatons only good enough to blow up — it seemed important. I was living in New York at the time, and a friend of mine had a gizmo that could pull the signal from the Russian satellite. We’d go drinking and then watch Russian morning shows in the middle of the night. It was apparent from watching these lovingly made kids shows that Russians weren’t quite the automatons that we’d been told they were. The song was also precipitated by my son asking me if there was a bomb that existed that could blow up the world, and I had to tell him, ‘Actually, yeah, there is.’ So he was introduced to that horror, the horror we’ve all lived with for most of our lives. It’s very cheeky to have stolen a bit of Prokofiev and stuck it in a pop song, but in that context it was right. (See more Sting comments on this song under “discography” at his website).

In the mid-1980s, with the escalating nuclear rhetoric, the outlook did not seem bright. And Sting’s song found its listeners. Around the world, the song rose on the pop charts.

U.K. rock star, Sting.

In his music, Sting has not been reticent about raising political matters, or incorporating current events into his songs, which he would continue to do throughout his career. In fact, on The Dream of the Blue Turtles album, in addition to “Russians,” there are two other “social concerns” songs — “Children’s Crusade,” about heroin addition, and “We Work the Black Seam,” about the 1984 U.K. coal miners’ strike and nuclear power plants.

Citizen Protest

Nuclear Freeze

Among the contributing reasons Sting’s “Russians” song found a receptive audience around the world was the fact that through the early and mid-1980s a U.S. and global activism had emerged around the idea of a “nuclear freeze” – meaning that the U.S. and Russia should then halt their nuclear build-ups, and move to de-nuclearize.

A very powerful global, grassroots and political movement emerged around this idea – to stop the nuclear arms race. It was helped along by scientific and popular initiatives that gave it “political legs” throughout the 1980s, to the point where even Ronald Reagan would soften his aggressive position, admitting at one point that a nuclear war could not be won.

Millions of people signed petitions and hundreds of thousands marched in street demonstrations in major cities. U.S. public opinion polls in 1982 and 1983 indicated an average of 72 percent supporting a Nuclear Freeze, with 20 percent in opposition.

Contributing to the popular sentiment supporting the freeze movement were scientific theories and projections of a possible “nuclear winter” – a prolonged global climatic cooling hypothesized to occur following a nuclear war (caused by bombing-induced firestorms that would inject soot into the stratosphere, blocking sunlight, resulting in widespread crop failure and famine).

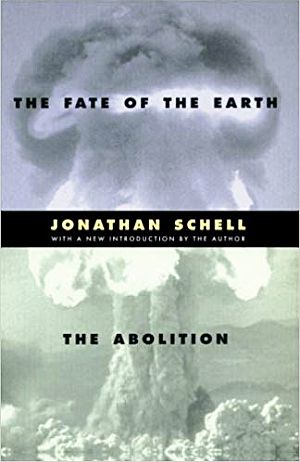

In early 1982, Jonathan Schell, a prominent journalist, wrote a series of essays for The New Yorker magazine that became a best-selling book, The Fate of the Earth, (March 1982) which cast nuclear war as global extinction event rather than a military-political battle between nation states.

In the U.S. Senate, Ted Kennedy(D-MA) and Mark Hatfield (R-OR) introduced a Freeze resolution in March 1982, and in May 1982, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a Freeze resolution by a vote of 278 to 149.

In November 1983, an ABC-TV film, The Day After – which followed the residents of a Midwestern city during and after a nuclear attack – also moved public opinion, as nearly 100 million Americans had watched the initial broadcast.

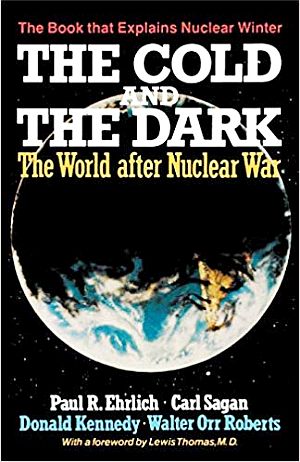

1984 book “The Cold and The Dark,” on nuclear winter, featured writing by Carl Sagan & others. Click for book.

Carl Sagan, a popular scientist, and his colleagues, published and promoted work on nuclear winter, which was adopted and advanced by activists to dispel the notion of surviving a nuclear war.

In 1984, The Cold and the Dark was published – the record of a 1983 Washington, D.C. conference of more than 200 scientists on the global climate and biological consequences of nuclear war, featuring two principal papers by Carl Sagan and Paul Ehrlich.

With the re-election of Ronald Reagan in the fall of 1984, and declining media attention to the nuclear issue, the nuclear freeze movement lost some of its steam and reorganized into various anti-nuclear, disarmament, and peace efforts. However, the Nuclear Freeze campaign in the U.S. and abroad can take credit for generating pressure that moved Ronald Reagan and his administration to reverse their hard-line stand, even to the point where Reagan – to the surprise of his Secretary of State, George Shultz – began privately entertaining the idea of proposing to his Russian counterparts that they eliminate all nuclear weapons.

In 1987, Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, in historic meetings, agreed to reduce nuclear arsenals as intermediate- and shorter-range nuclear missiles were later eliminated. In early November 1989, the Berlin Wall began to come down, and by December 31, 1991 the Soviet Union formally dissolved, ending the Cold War. The worry about nuclear weapons, however, did not dissipate, especially for those stockpiled in the Soviet Union during the Cold War that could now find their way to terrorists or rogue nations.

"Russians" - Sting, 2022.

“Russians” Redux

Fast forward to February 2022. Russia, under KGB-bred Vladimir Putin, invaded an innocent, peace-loving and independent Ukraine in a bloody and destructive war, seeking a military takeover there, while threatening European security and world peace. Once again, renewed Cold War fears and nuclear threats came to the fore, as Europe and NATO sought to sanction and isolate Russia for its insane aggression. And once again, as well, Sting’s “Russians” – nearly four decades after its first release – became relevant for another round of listening and consideration. In fact, in early March 2022, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Sting posted a video on Instagram of himself singing the song along with this note:

…“I’ve only rarely sung this song in the many years since it was written, because I never thought it would be relevant again. But, in the light of one man’s bloody and woefully misguided decision to invade a peaceful, unthreatening neighbor, the song is, once again, a plea for our common humanity. For the brave Ukrainians fighting against this brutal tyranny and also the many Russians who are protesting this outrage despite the threat of arrest and imprisonment – We, all of us, love our children. Stop the war.”

Sting also recorded an acoustic version of the song in 2022, with proceeds going to humanitarian and medical aid in Ukraine.

Over the years, Sting has used his talents to send other musical messages. A classic in this vein is his 1987 song, “They Dance Alone”(Gueca Solo), about women in Chile who assemble in quiet protest to dance “with the invisible ones” — their fathers, husbands, sons, and brothers — who “disappeared” in Chile, presumed tortured and murdered by the military dictatorship under Army General and President Augusto Pinochet (b.1915-d.2006). Sting, who witnessed one of these public dance protests, offered this explanation in liner notes on his 1987 album Nothing Like The Sun:“On the Amnesty Tour of 1986 the musicians were introduced to former political prisoners, victims of torture and imprisonment without trial, from all over the world. These meetings had a strong affect on all of us. It’s one thing to read about torture but to speak to a victim brings you a step closer to the reality that is so frighteningly pervasive. We were all deeply affected. Thousands of people have “disappeared” in Chile, victims of murder squads, security forces, the police, the army. Imprisonment without trial and torture are commonplace. The ‘Gueca’ is a traditional Chilean courting dance. The ‘Gueca Solo,’ or they dance alone, is performed publicly by the wives, daughters and mothers of the “disappeared.” Often, they dance with photographs of the loved ones pinned to their clothes. It is a symbolic gesture of protest end grief in a country where democracy doesn’t need to be ‘defended’ so much as exercised. (see more on this song, and more on Sting’s impressions of what he saw and experienced in Chile, under “discography” at Sting’s website).

Trudie Styler and Sting.

See also at this website, “Sting & Jaguar, 1999-2001,” on how Sting and Jaguar teamed up to help promote a new Sting song, and also, “LBJ’s Atomic Ad, 1964,” another Cold War tale that covers the onset of negative political advertising in American presidential campaigns. For additional story choices in politics please see the “Politics & Culture” category page, and for music, the “Annals of Music” page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

_________________________________

Date Posted: 30 April 2009

Last Update: 10 July 2023

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Sting: ‘Russians’, 1985,”

PopHistoryDig.com, April 30, 2009.

_________________________________

Books & Film at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“Khrushchev Tirade Again Irks Envoys,” New York Times, November 19, 1956, p.1.

“We Will Bury You!,” Time, Monday, November 26, 1956.

You Tube clip: Barry Goldwater’s Khruschev Clips, 1964 Election Ad.

Jan Sejna, We Will Bury You, Sidgwick & Jackson, London, England, 1982. Book on communist Cold War strategies by former communist general Jan Sejna of the Czechoslovak Army, who later emigrated to the U.S.

Nikita Khrushchev, Khrushchev Remembers, Little Brown & Co., January 1970.

“The United State Prepares for Nuclear War in the 1980s,” American Studies, Colorado.EDU.

“Russians,” Wikipedia.org.

Sting’s ‘Fields of Gold’ album, a Best-of-Sting compilation, which includes ‘Russians’ and ‘They Dance Alone,’ among others. Click for CD or digital.

Bernard Gwertzman, “Reagan Clarifies His Statement on Nuclear War,” New York Times Thursday, October 22, 1981, p. A-1.

Hon. Ronald Reagan, President of the United States, “Address to the Nation on National Security,” March 23, 1983, reprinted in Congressional Record, U.S. Senate, March 29, 1996, p. S-3206.

Lou Cannon, “Reagan Defends ‘Star Wars’ Proposal,” Washington Post, September 5, 1984, p. A-1.

Cass Peterson, “U.S. Won’t Abandon ‘Star Wars’,” Washington Post, December 24, 1984, p. A-1.

David Hoffman, “U.S. Firm In Pursuing ‘Star Wars’,” Washington Post, January 4, 1985, p. A-1.

Don Oberdorfer, “Reagan Claims ‘Star Wars’ Progress Does Not Violate Terms of ABM Pact,” Washington Post, October 13, 1985, p. A-11.

Sting Interview, Independent On Sunday (U.K.), November 1994.

Amy Argetsinger and Roxanne Roberts, “The Reliable Source: Mrs. Sting, Happy to Play Her Part,” Washington Post, April 1, 2009, p. C-3.