DVD cover for the epic, four-part 2021 Ken Burns PBS docu-series, “Muhammad Ali.” Click for DVD or video.

Burns is known for his in-depth treatment of subjects ranging from baseball and the Civil War, to Ernest Hemingway and country music. And the “Muhammad Ali” venture is no exception.

The first episode covers Ali’s life from 1942-1964 as a young boxer named Cassius Clay rises up the amateur ranks to win gold at the 1960 Olympics, to when he turns professional, discovering the benefits of self-promotion, then beating Sonny Liston to become heavyweight champion.

The second episode features Ali in the 1964-1970 period, joining the Nation of Islam, changing his name from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali, and refusing induction into the U.S. Army for religious reasons. A legal battle ensues that will eventually reach the Supreme Court.

This is the period when Ali is stripped of his boxing title – a champ without a ring for 3 years. Yet, with a couple of favorable local rulings in the late 1960s – one in Georgia and another in New York – Ali manages two return bouts, which he wins, though he is not in top form.

|

“Ali on Film” “A.K.A. Cassius Clay” |

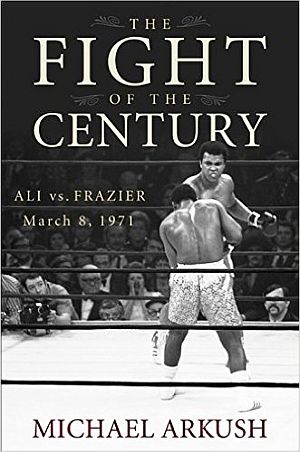

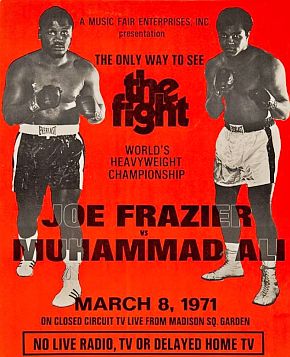

The third episode places Ali in his “rivalry years,” 1970-1974, when he and Joe Frazier, his fiercest rival, would have the first two of their three fights. Frazier wins the much-hyped first bout in March 1971, retaining the heavyweight title, and Ali – after a series of other fights – meets Frazier for the second time in January 1974, though Frazier by then had lost the heavyweight title to George Foreman. Ali wins the second fight with Frazier, thus becoming a viable contender to challenge then champ, George Foreman.

Part 4 of the Burns film covers Ali’s life from 1974 through his death in 2016. In October 1974, Ali shocks the world by defeating George Foreman in Africa at the much-hyped “Rumble in the Jungle,” winning back the heavyweight title. Also covered is the third Ali-Frazier fight held in the Philippines in October 1975 — the “Thrilla in Manila” – which Ali wins, besting Frazier in two of their three historic battles.

Although Ali loses and then regains the heavyweight title (for a record 3rd time) in a series of subsequent fights, the Burns film covers Ali’s later damaging bouts and staying in the fight game too long, and the development of his Parkinson’s disease. His post-retirement years after 1981 are also covered, as Ali travels the world spreading his Islamic faith, becoming a symbol of peace, hope and inspiration.

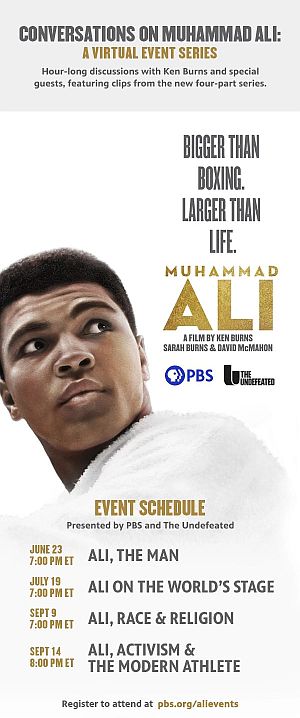

Part of the tag line used with the Ken Burns film is that Ali was “Bigger Than Boxing, Larger Than Life.” And the film lays out exactly why that’s the case.

Burns, for his part, has said: “I am drawn to boxing when the person and the bouts seem to reflect something larger…” And indeed, Muhammad Ali was in a league of his own, both as a superlative athlete and a man of conviction. His story is filled with a lot more than boxing. It is a biography of contradictions about a complicated human being.

And the Burns film covers that – his boasting and continuing dance with the media; his religious convictions; his fight against racism; his battle with the government over the draft; his marriages and his womanizing; his kindness and his cruelties; his compassion and his generosity, and more.

“We think we tell a story in a kind of complete way,” says Burns. And Ali’s daughter, Rasheda Ali, agrees: “This film, it’s the whole picture. It’s the good, the bad, it’s the inspiring, it’s everything.”

Yet, over the last 50 years, there have been numerous films on Muhammad Ali that have come before the Burns film.

In fact, between 1970 and 2020, when all the various versions are considered – documentaries, dramas, fictionalized accounts, and/or compilations – there have been some two dozen or so films that have been made about or with Muhammad Ali.

These films vary in quality and content, for sure, and there is a fair amount of repetition among them. Still, they tell us something of the man and his impact on culture, as well as those making the films. So, before getting into a bit more analysis of the Ken Burns film and its reviews, what follows here is a look back at some the Ali films that have preceded it.

1970

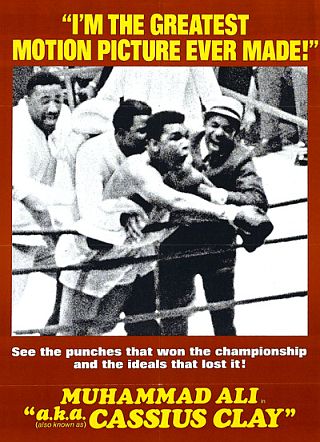

“a.k.a. Cassius Clay”

One of the first films on Muhammad Ali came in late 1970 – a documentary titled “a. k. a. Cassius Clay.” The film was made during the years Ali was banned from boxing for refusing the U.S. military draft during the Vietnam War and explores Ali’s career in his early years up until 1970.

As Wikipedia has summarized, “a. k. a. Cassius Clay” features “archival footage of people associated with Ali, such as Angelo Dundee, Malcolm X, and Drew Bundini Brown, and clips of his fights with Sonny Liston, Henry Cooper, George Chuvalo and Floyd Patterson. These are intercut with scenes featuring Ali and veteran boxing trainer Cus D’Amato discussing his career and how he would have fared against past champions such as Joe Louis.”

“a. k. a. Cassius Clay” was produced by Jim Jacobs and Bill Cayton, who would go on to manage another famous heavyweight, Mike Tyson. The film includes Ali clips from the vast collection of historic fight films compiled by Jacobs and Cayton, some of them familiar, but some quite rare, including some of Ali’s earliest bouts. Among these are Ali’s battles with Henry Cooper, Floyd Patterson, Jerry Quarry and Sonny Liston. Ali is also featured in film clips of his boastful self, proclaiming to be both the greatest and the prettiest fighter ever to enter a boxing ring – an attention-getting tact he adopted in part from “Gorgeous George,” a flamboyant pro wrestler of the late 1950s and early 1960s who adopted a similar style.

“a. k. a. Cassius Clay” is narrated by actor and famous “documentary voice,” Richard Kiley, who receives some notice from New York Times film critic, Roger Greenspun in a November 4, 1970: “It is difficult to imagine a dull movie from this material, and “a. k. a. Cassius Clay” isn’t dull. But it also isn’t as interesting as it might have been with more of Ali and his opponents, more of Malcolm X, more of Cus D’Amato—and rather less of Richard Kiley’s pointedly inconclusive narration….”

Greenspun continues his review in a more charitable vein with the following:

“…in treating the changing styles of a man who is always producing more or less lovely copy for the press, the film does pretty well. And whenever it enters the ring, of necessity, it does very well indeed. I don’t know anything about boxing, and I don’t even know what I like. But I am moved by Muhammad Ali’s supple body and flashing feet…

“…The best things in “a.k.a. Cassius Clay” concern the first Clay-Liston fight, where in the manner, the stance, the mere presence of the two men, a contest as if between two world orders seems to be taking place. Clay is, of course, brash and boastful and victorious. But Sonny Liston, throughout his training, the conferences, above all the prefight medical examination, suggests a grandeur, a kind of desperate invulnerability, like nothing I had seen in a movie before. It is as if the last of the great battleships, knowing its end was near, had transformed all its armament into one superb doomed image of invulnerability.”

David Stubbs, in one review blurb for “a.k.a. Cassius Clay” posted at Amazon.com, notes, in part: “…The principal pleasure is watching Ali in full verbal flow, including his maniacal teasing of Liston that proved to be a psychological knockout blow: ‘The man’s too ugly to be the world champ. The world champ should be pretty, like me!’.”

The one-and-a-half-hour film also addresses Ali’s self-promotion as well as how his much-publicized embrace of Muslim culture and faith altered his career. Among the many celebrities who also appear in this film are the Beatles, Malcolm X, Joe Louis and Sugar Ray Robinson.

Image used on some later editions of “a.k.a. Cassius Clay” in DVD and/or VHS formats. |

More than 30 years later, in early 2002, “a.k.a” appears to have received a second round of packaging and promotion when it was released as a DVD, in part for overseas markets, but also available in older formats such as VHS, as well as some streaming services and re-broadcasts on TV as late as 2011. The images above appeared as covers for the “a.k.a. Cassius Clay” film in those various DVD and VHS versions.

1974-75

“The Fight” / “Ali: The Fighter”

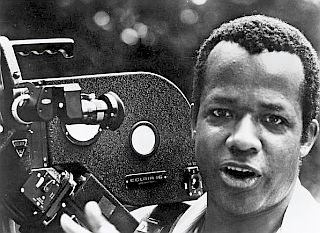

In 1971, William Greaves, described in some accounts as a “maverick film maker,” made a low-budget, 114 minute documentary about Muhammad Ali and his opponent, Joe Frazier. This film, first titled “The Fight,” was made ahead of the March 1971 “Fight of the Century” at New York’s Madison Square Garden – the much-touted contest billed, in part, as Ali’s big comeback following his suspension from boxing over his draft battle. Some notices described this film as a “behind-the-scenes documentary chronicling” the Ali-Frazier battle. Released in 1974, this film is also noted by other sources as “The Fighters,” and according to the American Film Institute, was cut to 93 minutes and reissued in 1975 with the title “Ali: The Fighter”. IMDB says that a 1977 version was also used for a network TV premiere, possibly with other cuts. During the film’s 1974 release, however, it received some positive notice, including a January 1974 New York Times review that called it “first-rate,” and a January 23rd, 1974 Variety review that commended the film’s insights into the social, racial and economic issues that surrounded the sport.

IMDB.com has offered this poster as one used for the 1974-75 William Greaves film, “The Fight”. |

In any case, a DVD of the film was later released under the “Ali: The Fighter” title, as shown above right ( Starz / Anchor Bay, 2005). And while the reviews are mixed, it seems that some fight fans find this film valuable. One reviewer at Amazon.com notes: “…There’s some great footage that captures the personalities of both Ali and Frazier. There is also some great training footage of each fighter. The tension of the prefight buildup is captured beautifully. The presentation ends with the actual fight…” But this reviewer also notes that film quality is not so good. Although another review from the Smithsonian adds: “…Greaves shot the match in its entirety from a dizzying array of camera angles, making the director’s cut… both an invaluable historical document as well as a virtuosic piece of filmmaking.”

William Greaves shooting footage for “The Fight,” his film on the March 1971 Ali-Frazier fight. Photo, John D. Kisch,

And finally, a later review of the first version of the William Greaves film, “The Fight,” appeared in The New Yorker by Richard Brody on June 13, 2016. That article was titled, “The Muhammad Ali Documentary That Gets to the Existential Heart of Boxing.” Brody offered the film as his personal favorite, calling it “a film of incisive reportorial analysis” for its detailed account of the events around one fight – the March 1971 Al-Frazier fight. “Greaves stages a mighty cinematic coup,” says Brody, by showing the entire Ali-Frazier fight, unadorned by commentary, music, or other add=ons – just the sounds of the audience. Brody wrote his praiseworthy piece on Greaves and his film after Ali had passed away, and when other films about him – but not “The Fight” – were then being re-aired in tribute on TV and cable.

1977

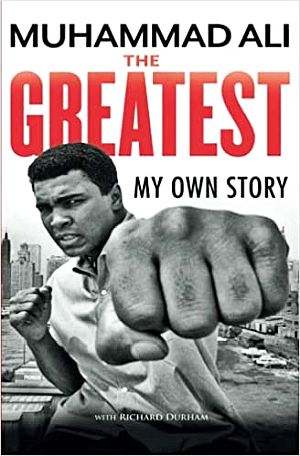

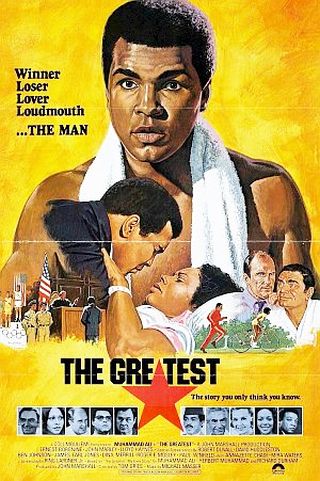

“The Greatest”

Poster for 1977 film about Ali’s life up to the late 1970s, starring himself and Hollywood actors Ernest Borgnine, James Earl Jones and Robert Duvall. Click for Amazon video.

The film follows Ali’s life from the 1960 Summer Olympics to his regaining the heavyweight crown from George Foreman in their famous “Rumble in the Jungle” fight in 1974.

The footage of the boxing matches themselves is largely the actual footage from the time involved. The film is based on the 1975 book, The Greatest: My Own Story, written by Ali and Richard Durham and edited by Toni Morrison.

Fresh from his gold medal victory at the Olympic Games, the film has the 18-year-old Cassius Clay ready to seek the heavyweight championship, under the guidance of his trainer, Angelo Dundee, played by Ernest Borgnine. James Earl Jones takes the role of as Malcolm X, while Robert Duvall plays Miami fight promoter, Bill McDonald.

In the film, Clay soon takes the title from Sonny Liston, later converting to the Islam religion and changing his name to Muhammad Ali. When he is suddenly classified 1-A by his local draft board – which had earlier rejected him – Ali refuses induction on religious grounds. He is then stripped of his boxing title. The film later shows him winning his three-and-a-half-year legal battle with the government and returning to the ring to resume his career, taking on opponents in some of the greatest fights of all time.

This film was directed by Tom Gries and Monte Hellman, with writer Ring Lardner, Jr., and producer John Marshall. The film’s soundtrack also included the song “The Greatest Love of All,” written for the film by Michael Masser and Linda Creed, sung by George Benson – a song later covered by Whitney Houston.

Among reviews of this film, Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times called it a “potent pop biography, lively and entertaining, in which the irrepressible world’s heavyweight boxing champion projects exactly the image he wants us to have.” Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film 2.5 stars out of 4, adding: “As a diverting entertainment, ‘The Greatest’ is more than satisfactory.” David Badder of The Monthly Film Bulletin stated, “‘The Greatest’ delivers exactly what one would expect: a hagiographical account of Ali’s best-known exploits, giving full rein to the inimitable, volatile personality but in the process applying liberal coats of whitewash.” And Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the film “a charming curio of a sort Hollywood doesn’t seem to make much anymore.”

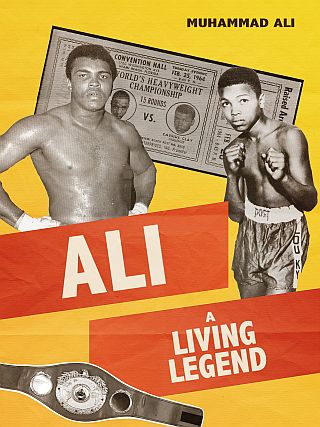

1980's “Ali: A Living Legend”, a 1980 film, was produced and narrated by NY TV host, Gil Noble. Click for later DVD.

1980

“Ali: A Living Legend”

A 1980 documentary, “Ali: A Living Legend,” covers two decades of Ali highlights and controversy. The 50-minute film is an early look at Ali’s career as an Olympic fighter through the 1970s, up until his World Championship.

The film was directed by Arnie Nocks and produced, written, and narrated by Gil Noble, a well-known TV personality at New York’s WABC-TV, who hosted a weekly African-American show, “Like It Is.” Noble also created documentaries on W. E. B. Du Bois, Malcolm X, Fannie Lou Hamer, Martin Luther King Jr., Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Jack Johnson, Charlie Parker, and Paul Robeson.

One reviewer of “Ali: A Living Legend” at Amazon noted: “The film shows a bit of wear and tear with age but still is interesting, often funny and inspiring. It’s not a comprehensive look at Ali’s life and career up until 1980, but gives you the highlights. The narrator [Gil Noble] also adds a couple of personal touches about his interviews with Ali…. And there are some very good boxing clips…”.

1996

“When We Were Kings”

Director Leon Cast’s Academy Award winner, “When We Were Kings,” (Ali-Foreman, 1974). Click for DVD.

The film – set in Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) – documents the build-up to what was then touted as the greatest sporting event of the 20th century. It follows the 32-year old Muhammad Ali as he starts training for the bout against Foreman.

“When We Were Kings” won an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature of 1996. In addition to footage of the actual Ali-Foreman title fight, which Ali won by knock out in the 8th round, it also offers additional content around later interviews conducted in the 1990s with Norman Mailer, George Plimpton, Spike Lee, Malik Bowens, and Thomas Hauser. These interviews describe the historical importance of the fight, their impressions of Ali, and fight itself. Also raised in the interviews was the matter of locating the fight in Zaire and accepting funding from then-dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko.

The interviews are accompanied by many news clips and photos that summarize Ali and Foreman’s careers leading up to the fight. There is also archival footage of celebrities, including James Brown, B.B. King, and promoter Don King, in the lead-up to the fight and accompanying “Zaire 74″ music festival. The When We Were Kings Soundtrack has received positive notice at Amazon.com and elsewhere, with buyers noting in particular, the music from “Zaire 74″ festival. A huge collection of the best black musicians from around the world was then included, among them: Bill Withers, BB King, James Brown, The Spinners, the Jazz Crusaders, and others.

“When We Were Kings” is regarded as one of the best boxing documentaries ever made, according to Wikipedia. The film was directed and produced by Leon Gast, who reportedly took 22 years to edit and finance it, but in the end, was rewarded with strong reviews, an Academy Award, and more than $2.7 million in global box office.

Region II DVD cover with actor Terrence Howard as Cassius Clay celebrating victory following first Sonny Liston fight.

January 2000

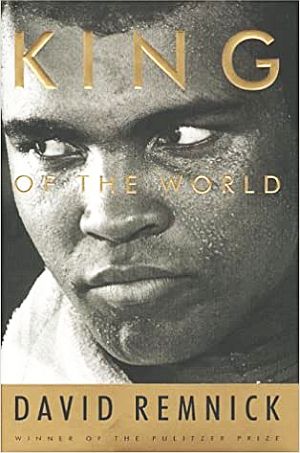

“King of the World”

“King of the World” is an American television film which aired on January 10, 2000 on the ABC network. It chronicles the early stages of the career of heavyweight boxer Muhammad Ali (then known as Cassius Clay, before he changed his name), who is portrayed by Terrence Howard. It is based upon a 1998 biography by David Remnick, King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero.

In the film, then Cassius Clay, having won the gold medal for boxing in the light heavyweight division at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome, Clay challenges professional heavyweight boxing champion Sonny Liston (Steve Harris) for the title. In the film, the media are portrayed as both intrigued and repulsed by Clay’s brash manner.

Despite being the underdog, the 22-year-old Clay shocks the sports world by defeating Liston by technical knockout in their February 1964 bout, becoming heavyweight champion and “king of the world”.

DVDs of this film are available for European and other markets, but not the U.S.

August 2000

“Ali: An American Hero,” aired on Fox-TV in August 2000, with actor David Ramsey as Ali. Click for DVD.

“Ali: An American Hero,” is an American television film produced by Fox Studios. It aired on August 31, 2000 on FOX-TV. The hour-and-a-half film chronicles portions of Ali’s career, portrayed in this film by David Ramsey.

The storyline follows the life of Ali through 1974 when he regained the Heavyweight Championship Title in the “Rumble in the Jungle” fight against George Foreman in Zaire.

Some reviewers at IMDB.com gave the film high marks. “Sherring,” writing in October 2002, gave the film a “10″ rating, noting, in part: “I thought the movie was overall pretty good…. The story flowed fairly well. I viewed the program on BET (a couple of times)…I have an easier time seeing Mr. Ramsey portraying Ali than someone like Will Smith or Terrance Howard… All in all I learned a lot about Mr. Ali from this movie and the complexity of his life…”

However, Phil Gallo, reviewing the film for Variety in August 30, 2000, writes, in part: “…This ‘Ali’ effort gets a steady performance out of David Ramsey as the most famous boxer of all, but there’s no sense of his importance or his inner turmoil…” “Ali: An American Hero” was released on DVD on January 27, 2004.

2001-2002

Will Smith’s “Ali”

In late 2001 came the Will Smith biopic of Muhammed Ali – titled “Ali” – with Smith in the lead role. The two-and-a half hour film, directed by Michael Mann, included supporting cast Mario Van Peebles, Jamie Foxx, and Jon Voight.

The film features Ali’s life in the peak of his career, from 1964 to 1974, from when he captured of the heavyweight title by beating Sonny Liston, to his conversion to Islam, criticism of the Vietnam War, and banishment from boxing, his return to fight Joe Frazier in 1971, and, finally, his reclaiming the title from George Foreman in the “Rumble in the Jungle” fight of 1974. The film also touches on the great social and political upheaval in the U.S. following the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

In the lead up to the film’s release, Smith and the production received a fair amount of press. In January 2002, Time magazine – for its European, Middle East and African editions of January 28 – featured Will Smith in character, along with the real Muhammad Ali, on that edition’s cover. There were also several stories inside that edition on the film, Smith, and Ali.

At its release, the film was well received by some, but not all, critics. Pulitzer prize-winning film critic Rogert Ebert wasn’t happy with the film overall, but he gave Will Smith good marks for his portrayal of Ali. “…[T]he key element of his performance,” wrote Ebert in December 2001, “is in capturing Ali’s enigmatic, improvisational personality. He gets the soft-spoken, kidding quality just right, and we sense Ali as a man who plays a colorful public role while keeping a private reserve…” For Ebert, “Smith is the right actor for Ali, but this is the wrong movie. Smith is sharp, fast, funny, like the Ali of trash-talking fame, but the movie doesn’t unleash that side of him, or his character…” The film, meanwhile, did not reach its box-office expectations. Smith and Jon Voight (who played sportscaster Howard Cosell), were nominated but did not win Oscar acting awards. Still, today, in retrospect, more than two decades later, some reviewers believe the film is “underrated”.

Time cover, January 28, 2002, used in Europe, Middle East and Africa, with Ali and Smith on the cover.

At the height of [Ali’s] 1960s troubles, when as a conscientious objector he has refused induction into the Army, when he’s been stripped of his title and not allowed to fight, someone asks Muhammad Ali if he even knows where Vietnam is. Sure, he replies. “It’s on TV.”

It is a cosmic moment in Ali, Michael Mann’s sober and often stirring film biography, a perfect representation of the instinctive, almost visionary, shrewdness that lay beneath Ali’s doggerel-spewing, hyperkinetic image. Bloodied and staggering under the blows of coarsely baying public opinion, he understood before most of us did that it was another kind of imagery–that selected by the media to symbolize the war to American civilians–that would determine the war’s outcome and his own fate….

The Ali Hollywood film – after getting permission from Ali on his 59th birthday to make the film – had an eight-year sojourn from initial idea to finished product. Filming began in Los Angeles on January 11, 2001 on a $105 million budget. Shooting also took place in New York City, Chicago, Miami and Mozambique.

Prior to making the film, Smith had rejected taking the role of Ali until the man himself requested that Smith accept it. Reportedly, the first thing Ali told him was: “Man, you’re almost pretty enough to play me.” In May 2000, Smith officially signed on with a $20 million salary. Smith spent about one year learning about Ali’s life. There was also extensive boxing training (up to seven hours a day), Islamic studies, and dialect training. Smith at the time, said that his portrayal of Ali was his proudest work to date. When Ali died on June 3, 2016, Smith was chosen to be one of Ali’s pallbearers for the memorial service in Louisville.

“…Made in Miami”

“Muhammad Ali: Made in Miami” is a 2008 documentary that explores the role that Miami played in the boxing and theatrical evolution of Ali. This film picks after Ali – then Cassius Clay – has won his 1960 Olympic gold medal in Rome.

Early in Ali’s career, his wealthy Kentucky backers were concerned about keeping him out of the clutches of the mob and they also wanted him to have a good trainer. So they arranged for a well-known trainer, Angelo Dundee, to help mentor and train Ali into a championship-caliber fighter.

That’s when Ali came to Miami to train with Dundee at Miami’s Fifth Street Gym. Dundee called the gym “The Theater” and it became one of the locations where Ali honed his boxing skills and also the place where he began to test his “performance art” of boasting and self-promotion, entertaining the press, celebrities, and drop-by visitors.

The PBS film looks at the years Muhammad Ali spent in Miami in the 1960s, his development during that period, and his life in Miami’s black community. It also includes some rare footage and interviews with Dundee, fight doctor Ferdie Pacheco, author Thomas Hauser, journalist David Remnick, and Ali’s Miami neighbors and friends. Ali’s relationship with Malcolm X is also covered as well as his early involvement with the Nation of Islam and its founder, Elijah Muhammad, and his conversion to the Islam faith following his victory over Sonny Liston to win the heavyweight crown in February 1964. The film ends soon after Ali is stripped of his boxing title because of his refusal to fight in the Vietnam War.

DVD cover for 2009 documentary film, “Facing Ali,” interviewing ten of Ali’s opponents. Click for DVD.

“Facing Ali”

“Facing Ali” is a 2009 documentary directed by Pete McCormack about Ali as told from the perspectives of ten of his opponents over the years – George Chuvalo, Sir Henry Cooper, George Foreman, Joe Frazier, Larry Holmes (also a former sparring partner), Ron Lyle, Ken Norton, Earnie Shavers, Leon Spinks and Ernie Terrell.

The film runs for more than an hour and a half, and covers the full scope of Ali’s career as told by his opponents – each of whom relay their own bouts with him while also discussing their own lives and careers.

Also covered are Ali’s fights against other opponents; his conversion to Islam; his taking the name Muhammad Ali; and his relationships with the Nation of Islam, its leader, Elijah Muhammad, and Malcolm X. Ali’s refusal to be inducted into the U.S. Army is also part of this story, as well as the New York State Athletic Commission stripping him of his championship title; Ali’s exile from boxing and his ongoing legal battle, up through his reinstatement following June 1970 U.S. Supreme Court’s 8-0 ruling in his favor.

Glowing reviews for “Facing Ali” come from a number of the more than 330 users who rated the film at Amazon.com, where it has also received an “Amazon’s Choice” banner. Production is credited to Canadian producer Derik Murray and his company, Network Entertainment, and to LionsGate Entertainment and Spike Sports in association with Muhammad Ali Enterprises. The film won awards at the Vancouver Film Critics Circle and the Vancouver International Film Festival.

“Champions Forever”

“Champions Forever: The Definitive Edition,” was released as DVD in October 2009. At Amazon.com, it’s description includes the following:

“These are the lost interviews… Filmed at [Ali’s] home in Michigan and during the making of ‘Champions Forever’ – the acclaimed documentary that brought together Ali, Joe Frazier, George Foreman, Larry Holmes, and Ken Norton for the first and only time… These 1990 interviews with Craig Glazer were placed in a vault and forgotten for nearly 20 years until rediscovered by producers Craig Glazer and Ron Hamady.

In these never before seen conversations, a playful, feisty, and inspiring Ali talks about his place in history, his love for his fellow heavyweight champs…”

As of September 2021, this DVD had received 110 ratings at Amazon.com – one of which notes: “Wonderful candid footage of Muhammad Ali and other champions. I have watched it over and over again. I think I own almost every DVD there is of Ali, but ‘Champions Forever” brings tears to my eyes.”

2012

“Ali: The Man, The Moves, The Mouth”

In 2012, a documentary titled, “Ali: The Man, The Moves, The Mouth” was released. The film is narrated by Bert Sugar, noted boxing analyst and sportscaster.The one-hour film purports to capture Ali’s moves both inside the ring and his boasting outside of it – “and the legend they engendered.”

The film compiles some of Ali’s best moments in the ring, as well as “many of his most outrageous and memorable interviews with reporters and on television.”

Dozens of fight highlights are used, including those from the Ali-Frazier bouts and the George Foreman fight. As of late September 2021, this film had received 102 ratings at Amazon.com.

An earlier edition of this film appears to have been released in 2008 as a book-DVD combination, titled: Ali in Action: The Man, The Moves, The Mouth, with a 160-page illustrated hardback book published by Lyons Press.

The book in this set is written by sportswriter Les Krantz with an introduction by Angelo Dundee. That book-DVD set is described at Goodreads.com as follows:

…Now for the first time ever, sparkling clear sportswriting has been melded with DVD technology to bring together Ali’s brilliant ring moves, his colorful rhetoric, and historic photos of his career. Here you’ll find rare footage of Ali’s famous “Pearls of Wisdom,” as well as highlights of fights such as the “Thrilla in Manila” and the “Rumble in the Jungle” that have generally been blacked out until now. The masterfully composed book contains details and highlights from Ali’s youth and his Olympic gold medal win as Cassius Clay, to his battle against Parkinson’s Disease and carrying the torch at the opening of the 1996 Olympic Games. This is the all-time monument to the 20th century’s greatest athlete, a must-have for sports fans and anyone who wants to remember this legendary champion and American icon.

2012

“When Ali Came To Ireland”

Poster for the 2012 film, “When Ali Came to Ireland,” which chronicles Ali’s visit to Ireland in July 1972 when he fought and defeated American opponent, Alvin Lewis, and also visited with Irish media.

“When Ali Came to Ireland” is a 2012 Irish documentary film directed by Ross Whitaker. It tells the story of how Killorglin-born circus strongman and publican, Michael “Butty” Sugrue, put up £300,000 and persuaded Muhammad Ali to make his first visit to Ireland to fight against American Alvin Lewis in Croke Park on July 19, 1972.

Ali traveled to Ireland with his entourage in advance of the scheduled bout to spend time training for the fight. While there, he was interviewed for RTÉ Television. Ali won the Lewis fight with a technical knockout in the 11th round, but reportedly, Mr. Sugrue lost a lot of money backing the fight. The documentary film was first broadcast on RTÉ One on January 1st, 2013. Ali returned to Ireland twice in later years. In 2003, he took part in the opening ceremony of the Special Olympics in Dublin.

2013

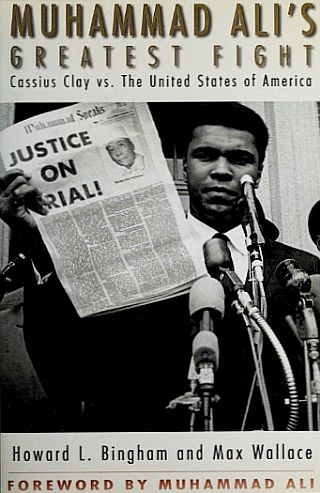

“Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight”

Poster for 2013 film, “Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight,” which covers his military draft legal battle. Click for film.

The film, based on the actual case, Clay v. the United States of America, premiered on HBO on October 5, 2013.

The film was directed by Stephen Frears (“The Queen,” “High Fidelity”). The screenplay was written by Shawn Slovo based on the 2000 book, Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight: Cassius Clay vs. the United States of America, by Howard Bingham and Max Wallace.

Muhammad Ali in 1967 had been convicted in federal court for refusing to be inducted in the military in 1966 (when he was Cassius Clay), and was sentenced to serve five years in prison, but remained free while he appealed his case. It was during this time that he was stripped of his heavyweight title and lost his license to box, suffering more than 3 years in limbo awaiting legal resolution.

His appeal, meanwhile, eventually made it to the U.S. Supreme Court, where it initially appeared to have no chance of reversal, since 5 of then 8 eligible justices had privately indicated opposition to the appeal, voting 5-3, after its first hearing (the ninth Justice, Thurgood Marshall, had removed himself from the case because he had been U.S. Solicitor General when the case began. Marshall, in fact, played by Danny Glover in the film, wasn’t altogether thrilled with Ali in any case, as Marshall viewed him as a segregationist).

Cover of book by Howard Bingham & Max Wallace that becomes the basis for the 2013 film. Click for copy of book.

The court was then in its 1970-71 session, under chief Justice Warren Burger (played in the film by Frank Langella). Burger assigns conservative Justice John Harlan II (played by Christopher Plummer) to write the opinion on what is then expected to be the court’s 5-3 vote denying Ali’s appeal.

Harlan, a conservative, enlists his liberal law clerk Kevin Connolly (a composite character in the film) to help write and research the opinion.

Connolly, however, after reading background on the Black Muslims, comes to the position that Ali’s beliefs did fulfill all the conditions for conscientious objector status – which the Justice Department in earlier oral argument had dismissed.

At first, Justice Harlan does not agree with his young aide, but later reads the clerk’s brief and material on the Black Muslims, and then reverses his earlier vote, now siding with Ali and his appeal. Harlan even incorporates Black Muslim information into his opinion while also finding that the Justice Department had misrepresented Clay’s position. Meanwhile, a draft of Harlan’s opinion then began to circulate among the other Justices.

In their 1979 book on the Supreme Court, The Brethren, Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong include a section on the Clay v. U.S. case, noting some of the internal dynamics at the court when Harlan reversed his vote, especially Chief Justice Warren Burger’s reaction:

“…[W]hen [Harlan’s] memo suggesting reversal of the conviction was circulated, it exploded in the Court. Burger was beside himself. How could Harlan shift sides without notifying him? He was even more irritated by the incorporation of Black Muslim doctrine in the opinion. The draft said that Black Muslim doctrine teaches ‘that Islam is the religion of peace…. and that war-making is the habit of the race of devils [whites]. . . [and that Islam] forbids its members to carry arms or weapons of any kind.” Harlan had become an apologist for the Black Muslims, Burger told a clerk…..”

Burger and a couple other Justices were also not happy that the government’s misrepresentations would be exposed with Harlan’s opinion. Harlan’s view could also mean that all Black Muslims might then be eligible for conscientious objector status.

Harlan’s switch, however, meant that there would be a 4-4 tie in the Court’s vote. That, however, was no better for Ali since a tie vote would not reverse Ali’s conviction. Harlan then considered trying to persuade another Justice to join him to make it a 5-3 vote in favor of Ali. But that did not occur. However, another course did, one that offered the court a more amenable exit.

In the appeals process that had brought Clay/Ali’s case to the Supreme Court, the state Appeal Board, where Clay had made an appeal, denied his claim, but that Board did not specifically state its reason for the denial. This was later seized upon by Justice Potter Stewart in his review of the case as a Justice Department technical error. And that became a more agreeable basis for the high court in two ways. First, it would not become precedent; and second, it would not broaden the categories under which others might claim to be conscientious objectors.

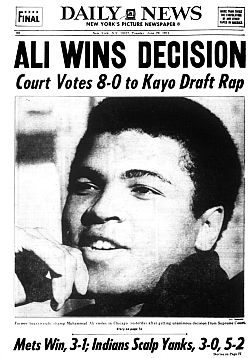

June 29, 1971, New York’s “Daily News,” on the Supreme Court ruling in Ali’s favor.

Ali received the news in Chicago. “I thank Allah,” he said, “and I thank the Supreme Court for recognizing the sincerity of the religious teachings that I’ve accepted.” But Woodward and Armstrong added in their book, “he did not know how close he had come to going to jail.”

The 2013 HBO film, meanwhile, is essentially true to the actual case. And although Ali only appears in news footage, the story is nonetheless an important part of his history. However, since it dwells on the legal details of the appeal and the Supreme Court’s back-chambers process, the film may be a bit too technical and wonky for many viewers. Still, it is a key bit of history in the story of Muhammad Ali and his future following that decision, as well as a glimpse at how America’s legal system worked through an appeal of this kind during a time of high socio-political tension. As of this writing, the film has received 71 ratings at Amazon.com, an “Amazon’s Choice” banner, and a number of praiseworthy user comments at IMDB.com as well.

2013-2014

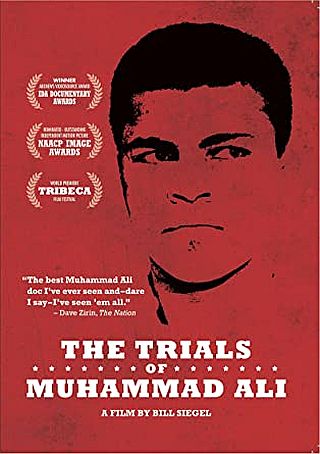

“The Trials of Muhammad Ali”

2013 documentary film, “The Trials of Muhammad Ali,” directed by Bill Siegel. Click for DVD or streaming.

The documentary is “no conventional sports documentary,” according to one blurb at Amazon.com. The film investigates Ali’s “extraordinary and often complex life.” Given his “outspoken and passionate beliefs… Ali found himself in the center of America’s controversies over race, religion, and war.”

Louis Farrakhan, Robert Lipsyte, John Carlos and Angelo Dundee are among those interviewed in this film, with archival footage of others, including: Ali, George W. Bush, David Susskind, Lyndon Johnson, Jerry Lewis, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Elijah Muhammad.

The film began showing at various U.S. film festivals in 2013 and had its premier in April 2014. Kartemquin Films is the production company, known for other documentaries, such as, “Hoop Dreams” and “The Interrupters.” Academy Award-nominated Bill Siegel is the director, known for his other work, including, “The Weather Underground.”

“‘The Trials of Muhammad Ali,’ says Amazon.com, “examines how one of the most celebrated sports champions of the 20th century risked his fame and fortune to follow his faith and conscience.” Dave Zirin of The Nation magazine, gives the film a positive blurb that appears on the DVD cover, noting:: “The best Muhammad Ali doc I’ve seen and — dare I say – I’ve seen ‘em all.” The film won an award from the International Documentary Association in 2014 for Best Use of News Footage. As of October 2021, the film had received 63 user ratings at Amazon.com and also an “Amazon’s Choice” banner.

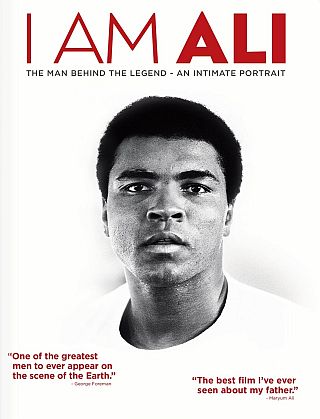

British filmmaker Clare Lewins’ 2014 film, “I Am Ali,” includes use of Ali’s audio journals. Click for DVD or streaming.

“I Am Ali”

“I Am Ali: The Man Behind the Legend – An Intimate Portrait,” is a 2014 documentary directed by filmmaker Clare Lewins made with the help of personal audio recordings Ali made during his career.

Lewins is a British filmmaker who had made an earlier TV program on Ali for the BBC. In that process, she had come to know Ali’s former business manager, Gene Kilroy, who helped her gain access to the boxing world and to Ali’s daughters, Hana Ali (daughter of Ali and Veronice Porche) and “May May” or Maryum Ali (Ali’s eldest daughter from his marriage to Belinda Boyd / Khalilah Ali).

But what Lewins discovered in coming to know the daughters, was that Hana had a collection of recording tapes made by her father of conversations and phone calls he had with family and friends in the 1970s and 1980s. Hana was using these tapes to write her own book about her father (At Home with Muhammad Ali: A Memoir of Love, Loss, and Forgiveness), but Lewins eventually was given access to the recordings, and some are used throughout “I Am Ali.” Additionally, interviews with friends, family members, and some boxing rivals, along with archival footage of Ali, are used as well. Notable appearances include George Foreman, Jim Brown, and Mike Tyson. The film is also backed with a generous selection of popular 1970s music, including R&B and soul hits from Stevie Wonder, Bill Withers, the Staple Singers and others.

The reviews were generally positive, some acknowledging the film was more about the personal Ali interacting with family than a boxing film. One Chicago Tribune review noted: “At its best, ‘I Am Ali’ offers something the big-budget biopic ‘Ali’ could not: casual intimacy.’ Reviewing the film for National Public Radio, Chris Klimek, wrote: “What distinguishes Lewins’ entertaining-if-not-terribly-revelatory film from the many Ali documentaries that have come before is its focus on this most public of personalities as a friend and father.” The Guardian newspaper of London called the film “warm hearted and respectful” and a “very watchable tribute.” The DVD has 415 user ratings at Amazon.com.

2019

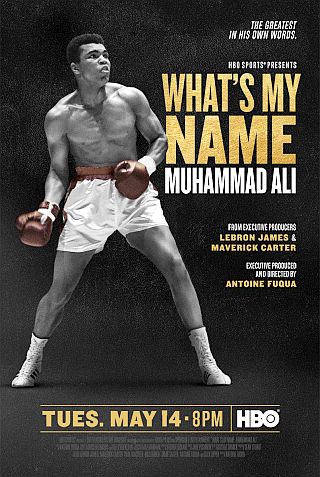

“What’s My Name: Muhammad Ali”

Promotional poster for HBO’s 2-part, 2019 documentary film, “What’s My Name: Muhammad Ali.” Click for film.

The film, which aired at Tribeca in late April 2019 premiered on HBO in May 2019, with each segment running about 80 minutes. “What’s My Name” is directed by Antoine Fuqua whose other films have included “Training Day” (2001), “The Equalizer (2014), “The Magnificent Seven”(2016), and others.

“Muhammad Ali had a deep impact on me from an early age,” says Fuqua. “Being given the opportunity to tell his story, both inside and outside the ring, is a privilege and a dream come true.”

Basketball star LeBron James, and sports-marketing businessman Maverick Carter, served as executive producers for the film. “Muhammad Ali transcended sports in a way the world had never seen before,” says executive producer LeBron James in a statement at the film’s website. “It’s an honor to have the opportunity to tell his incredible and important story for the coming generations. He showed us all the courage and conviction it takes to stand up for what you believe in. He changed forever what we expect a champion to be, and I’m grateful that SpringHill gets to be a part of continuing his legacy.”

In his review, Brian Tallerico at RogerEbert.com wrote that the film “offers something even for those of us who know a great deal about the legendary athlete and civil rights leader by doing something incredibly simple: letting Ali tell his own story.” Caryn James of The Hollywood Reporter wrote, “With montages of Ali meeting the Pope and Nelson Mandela, and newspaper headlines about donations to help fight poverty in Africa, ‘What’s My Name’ is undeniably an exercise in image-burnishing (not that Ali’s already heroic image needs it). But this smartly crafted film holds you all the way.” “What’s My Name” was a 2019 Sports Emmy winner for Outstanding Long Documentary. An 18-song instrumental soundtrack for this film was also issued – What’s My Name: Muhammad Ali (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack), by Marcelo Zarvos, available in MP3 format at Amazon.com.

2018-2020

“Ali & Cavett: The Tale of the Tapes”

Muhammad Ali made numerous appearances on The Dick Cavett Show, a popular TV talk show in the late 1960s through mid-1970s. Cavett’s show was favored by viewers who liked to hear about politics and social issues as well as celebrity banter. In a 2018 New York Times piece, Cavett and his show were described by Alex Williams as follows:“….For three decades, Mr. Cavett was the thinking person’s Johnny Carson, embodiment of an East Coast sophisticate. He wore smart turtlenecks and double-breasted blazers, had more cultural references than a Google server and laced martini-dry witticisms into lengthy, probing talks with 20th-century luminaries including Bette Davis, James Baldwin, Mick Jagger and Jean-Luc Godard…. ‘The Dick Cavett Show’ was woke some 50 years before the term came into vogue. Viewers tuned in to see Muhammad Ali spout off about the Vietnam War or to see Yoko Ono show her conceptual art in a 90-minute discussion with John Lennon.”

Among guests appearing on his show were the likes of Norman Mailer, Woody Allen, David Bowie, Marlon Brando, and others. Muhammad Ali was a guest on Cavett’s shows more than a dozen times, starting with a 1968 appearance booked less than a year after he had been stripped of his heavyweight boxing title for refusing the U.S. military draft during the Vietnam War.

Rev. Al Sharpton was among those interviewed for the Cavett documentary, and has noted that Cavett “was the whitest of white guys in America. But he gave blacks that had been considered outside of the mainstream — like Ali — a chance to be heard, and a chance to say what they wanted to say unfiltered….” According to Sharpton, Ali “would say things to Cavett about whites that you’d hear on the street corners in Harlem…They seemed to go to the edge of the racial debate [at that time].”

In addition to Sharpton, others interviewed for the “Ali & Cavett” documentary, include: Ali biographer Thomas Hauser, columnist Juan Williams, author Ilyasah Shabazz, and boxing commentator Larry Merchant. These interviews are combined with footage from Ali’s past appearances on Cavett’s show.

Muhammad Ali appearing on “The Dick Cavett Show,” a popular late-night TV talk show, circa, 1960s-1970s.

According to the Los Angeles Times, Cavett’s first encounter with Ali had come in 1963 when he was a writer for “The Jerry Lewis Show,” where he was charged with giving Ali a poem to perform. But earlier that evening, Cavett had seen Ali outside the El Capitan Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard where the young rising boxer had drawn a crowd (by then Ali was17-0 in his early professional bouts, pre-Liston). “It was like seeing a god,” said Cavett. “People were just standing there in awe, just stricken by his presence, and it was really a wonderful thing to see and feel. He had what you call ‘it.’” Cavett and Ali, in fact, developed a lifelong friendship that lasted some 50 years – with Ali staying as a guest at Cavett’s home on occasion, and Cavett going to the champ’s Pennsylvania training camp or joining him on other outings.

“Ali and Cavett: The Tales of the Tapes,” originally aired at SXSW in 2018. By January 2020, Cavett had appeared on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert promoting the film as an HBO special. In June 2020, when the 90 minute documentary was scheduled for use on Sky networks’ documentaries channel, a review in The Independent newspaper of London noted: “While ‘The Tale of the Tapes’ doesn’t teach us much, it underlines Ali’s gift for entertaining and turning sporting achievement into a metaphor for something bigger.”

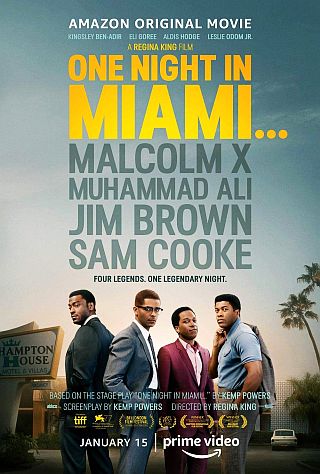

“One Night in Miami…”

“One Night in Miami…” is a 2020 American drama film from Amazon Studios. It is a fictionalized account of a February 1964 meeting of Muhammad Ali and three of his close friends that took place on the night he had won the heavyweight boxing title by defeating Sonny Liston.

Rather than partaking in a wild party after his victory, in this account, Ali (then Cassius Clay), celebrates privately in a Miami hotel room with three close friends: activist Malcolm X, singer Sam Cooke, and American football star Jim Brown.

But their meeting is about more than just celebration.

As one Amazon.com summary of the screenplay describes it: “…[I]n that hotel room… were four men who understood each other and their moment in history in a way that no one else could. With the Civil Rights movement stirring outside, and the melody of A Change is Gonna Come [Sam Cooke hit song] hanging in the air, these men would emerge from that room ready to define a new world.”

In his review at Variety, Owen Gleiberman praised the characters in the film, as well as its parallels to modern day: “One Night in Miami is a casually entrancing debate about power on the part of those who have won it but are still figuring out what to do with it.”

The film was adapted from the award-winning 2013 stage play of the same name, written by Kemp Powers, later released as a short book (see below). Kemp’s writing, for the play and film, won plaudits from a wide range of critics. The film was directed by Regina King making her feature film directorial debut. Cast in the lead roles are: Kingsley Ben-Adir as Malcolm X; Eli Goree is Cassius Clay; Aldis Hodge plays Jim Brown, and Leslie Odom Jr. is Sam Cooke.

Amazon Kindle edition of screenplay for “One Night in Miami...,” also available in paperback. Click for Amazon.

At the Miami meeting itself, internal criticisms flow among the participants as they grapple with the issues of the day. Malcolm criticizes Cooke’s music as selling out to white audiences, and Clay criticizes Malcolm for planning a split from Elijah Muhammad.

Following their meeting that night, Cassius Clay would change his name to Muhammad Ali; Sam Cooke would debut his hit song, “A Change Is Gonna Come” on The Tonight Show; Jim Brown would leave the NFL to pursue a movie career; and Malcom X’s home would be firebombed after his split with the Nation of Islam and he is later assassinated in New York.

At the 93rd Academy Awards, “One Night in Miami…” earned three nominations: Best Supporting Actor for Odom, Best Adapted Screenplay for Powers, and Best Original Song (“Speak Now”). The film was released in a few theaters on December 25, 2020 before Amazon released it digitally on Prime Video on January 15, 2021. The film is also available in a Criterion Collection edition (after December 7, 2021). At Amazon.com, meanwhile, the film has received more than 3,500 user ratings.

2021

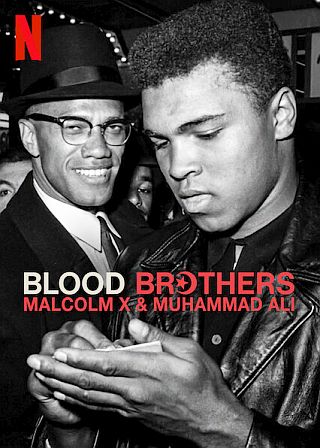

“Blood Brothers: Malcolm X & Muhammad Ali”

2021 Netflix film: “Blood Brothers Malcom X and Muhammad Ali,” available at Netflix.com.

In the early 1960s, when Cassius Clay was considered an obnoxious self-promoter by many, Malcolm X, a rising minister for the Nation of Islam, saw potential in Clay beyond the boxer. Eventually, in Ali’s early career, the two formed a close friendship. But few really understood the bond that developed between them.

In her review of the film, Sheila O’Malley at RobertEbert.com, explains: “Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X were two very different men, from two very different places, but they both understood that one of the primary threats to Black Americans was the racist culture’s relentless attack on the mind. They both stood as bold examples of what a free mind looked like, what a free mind could do.”

In the film, each man’s biography is presented separately, telling their respective stories, Malcolm X first, and then Cassius Clay. This gives context to their meeting and friendship. Book authors, Roberts and Smith are also interviewed, helping to frame the story and timeline. There are also on-camera interviews with people who knew Ali or Malcolm X personally, including their adult children. Other comment comes from Cornell West from Harvard, Todd Boyd, professor of media studies at USC, and oral historian Zaheer Ali.

Malcolm-X was a former convict turned intellectual revolutionary who spoke out quite eloquently against the evils of racism and white oppression, becoming a rising minister in the Nation of Islam. When he met the young boxer, Cassius Clay, in 1962, the two were seemingly worlds apart.

2016 book used as basis for the 2021 film. “Blood Brothers,” first published by Basic Books, 400pp. Click for book.

Malcolm, some 17 years older than Clay, became his tutor, schooling him in the tenets of Islam and becoming a primary influence on his conversion to that religion. But during Ali’s early boxing career, his relationship with Malcolm and Islam was kept out of the public limelight for fear it would jeopardize his boxing career. The Nation of Islam was more militant to the racial divide in America than the non-violent methods espoused by Martin Luther King, and quite separatist in outlook. And Ali and Malcolm, espousing the Nation of Islam’s tenets, were initially vilified by many whites and white media.

Beyond Islam, Malcolm and Ali became close friends, involved with one another’s families and developing genuine affection for one another. But there came a time when the two had a bitter parting of the ways, as Malcolm became less and less enamored with the methods and behavior of leader Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam. When Malcolm split from the Nation to form his own sect, Ali renounced him. By May 1964, when Malcolm X and Ali crossed paths in Ghana – barely three months after Ali had won the boxing championship and had publicly announced his conversion to Islam with Malcolm X at his side – Ali essentially snubbed his former friend and mentor and would have nothing to do with him thereafter. For Ali, their friendship was over; not even moved after Malcolm was assassinated in 1965. It was a grudge Ali would carry for decades, only regretting many years later how he had treated Malcolm. “Turning my back on Malcolm was one of the mistakes that I regret most in my life,” Ali later wrote. “I wish I’d been able to tell Malcolm I was sorry, that he was right about so many things… He was a visionary — ahead of us all.”

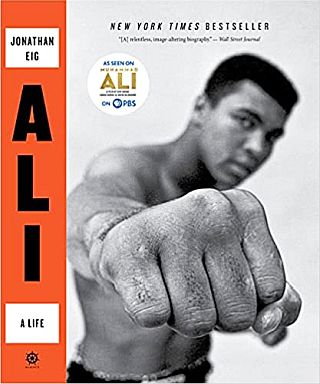

Jonathan Eig, author of 2017 book, “Ali: A Life,” encouraged and shared source material with the Ken Burns Ali film project. His book is an Amazon “editors’ pick.” Click for copy.

2014-2021

Enter Ken Burns

Ken Burns and co-producers – daughter Sarah Burns and husband, David McMahon – began their Muhammad Ali film project in 2014. And despite the fact that there had already been a number of films about the boxer, they discovered, partly through the urging of author Jonathan Eig, that there was still more to tell about Ali and his life. Eig, then working on his book, Ali: A Life, later published in 2017, believed Burns could do a film on Ali that hadn’t been done before, and he would also help them with source material.

As Sarah Burns would later explain in a New York Times story, they realized “just how much there was to this story.” Not just the boxing, she would explain, “but his relationships with Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad, his family life, his marriages, his draft resistance and his courage and being willing to go to jail for his convictions, and also his battle with Parkinson’s…[and] his later life, his post-boxing life.”

Along they way, they found some surprises – and a few new troves of Ali information. Unexpectedly, some abandoned film from a failed production company was found in a Pennsylvania archive that was simply labeled “Ali.” Turned out it was some never-seen-before good quality, Technicolor 16-millimeter ringside footage from the “Thrilla in Manila” Ali-Frazier fight. The team also worked through more than 15,000 photos during the project.

They also talked with a range of people in making the film, many of whom appear on camera to good effect – boxer Michael Bentt; sports writer David Kindred; former sparing partner and opponent in the ring, Larry Holmes; sports writer Howard Bryant; pro basketball star and Ali friend, Karreem Abdul-Jbbar; poet and activist Nikki Giovanni; civil rights activist Jesse Jackson; boxing promoter Don King; writer Gay Talese; New Yorker editor and author David Remnick; Todd Boyd, Gerald Early, novelist Walter Mosley; Islam scholar Sherman Jackson; poet Wole Soyinka; and Ali’s grown children, family members, and former wives.

Press notice for “discussion sessions” with Burns team in advance of September 2021 PBS film release.

Burns and company worked with the full, broad palette that was the unfolding life of Cassius Clay / Muhammad Ali – not a one-dimensional character, for sure. And Burns clearly saw this in his subject’s appeal: “Maybe you’ll come for the boxing. Maybe you’ll come for the religion. Maybe you come for the politics or the conflict. But I think you’ll leave with an elevated sense of an amazing American.”

In a 2021 segment on the Bob Costas HBO show, Burns and Ali daughter, Rasheda, appeared to discuss the film, as Costas asked Burns this question:

Bob Costas: “I’ve heard you say that Muhammad Ali is as relevant today as he was then…”

Ken Burns: “Absolutely…. This is a guy who intersects with all the major themes of the last half of the 20th century: the role of sport in society; the role of a black athlete; the nature of black manhood and masculinity; race; civil rights; war; politics; faith; religion; sex – all of these things. We’re grappling with them still today, and he’s there as a kind of beacon, and a guide. And he’s incredibly contradictory at times. He’s an irresistible subject…”

Indeed he is, and the Burns film lays out why — collecting kudos for doing so on the review circuit.

Caroline Framke, writing for Variety.com, lauded the film for “bringing fresh insight to a story so many think they already know. Whether or not you understand the breadth of Ali’s impact going into this series, you should leave it gaining a new appreciation of how he gained and wielded his influence in a way no other athlete had before, or has truly done since.”

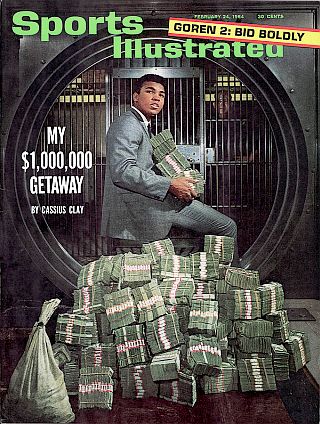

Sports Illustrated, in their pre-Sonny Liston-Cassius Clay fight edition of Feb 24, 1964, featured 22 year-old Clay on its cover with an actual pile of real money in front of a bank vault, for an essay Clay would write, using the cover tagline, “My $1,000,000 Getaway” (his projected take in the upcoming fight).

“The Ali Effect”

Despite all the films on Ali — and the epic Ken Burns treatment – there is still more to consider. For one, it might be interesting to have some accounting of his considerable economic impact. From the money he made, yes, but more importantly, to the money he made for others, the business activity generated around his life and brand, and how a global icon like Ali comes to have a national and global economic impact.

In boxing, of course, there are the tens of millions Ali made with his share of the gate receipts generated in each of his fights – variously estimated in the $30-$40 million range. (In 2006, Forbes listed Ali on its Top 100 Celebrities list, citing a net worth of $55 million).

But others around Ali and his fights – investors, sponsors, closed-circuit TV, gambling operations, vendors, the Nation of Islam, and more – also made money, and for some, enormous amounts of money.

The films listed in this story indicate a small portion of the “Ali effect” that has swept across the sports/entertainment economic realm.

Even the Sylvester Stallone/Rocky franchise – now with eight Rocky/Creed films exceeding a $1.5 billion total box office – dates its origin to Ali’s 1975 fight with Chuck Wepner, where Stallone first got the idea for “Rocky 1.” And the Apollo Creed character introduced in that first film is clearly a spin off of early Cassius Clay.

Beyond film, of course, Ali artifacts of every conceivable kind are out there – books, games, posters, toys, clothing, advertising, athletic centers, and more. From the smallest tourist curios and bobblehead type products, to the foundations and charitable funding his name has generated for social change, education, and economic opportunity, there is quite a large economic “Muhammad Ali effect” to consider. Some of this has already been covered in Ali biographies and scholarly works, but a good documentary on this part of his impact might prove to be a worthwhile and enlightening addition.

See also at this website, “Ali-Frazier History,” a detailed story on the much-hyped first March 1971 fight between Ali and Joe Frazier, their two subsequent matches, and their embattled relationship during those years and into retirement. See also the “Annals of Sport” and “Film & Hollywood” category pages for story choices on those topics. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing, and continued publication of this website. Thank you – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 19 October 2021

Last Update: 19 October 2021

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Ali’s Film History: 1970-2021,”

PopHistoryDig.com, October 19, 2021.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

PBS Website, “Muhammad Ali: A Film By Ken Burns, Sarah Burns and David McMahon,” PBS.org, September 2021.

The Films, “Muhammad Ali,” KenBurns.com.

Thomas Page, “10 Things We Learned About Muhammad Ali From Ken Burns’ Epic Documentary,” CNN.com, September 15, 2021.

Melanie McFarland, “Ken Burns’ New ‘Mu-hammad Ali’ Docuseries Is Worth Going the Distance,” Salon.com, September 19, 2021.

“Muhammad Ali,” Wikipedia.org.

“Muhammad Ali in Media and Popular Culture,” Wikipedia.org.

“Category: Films About Muhammad Ali,” Wik-ipedia.org.

“Boxing Career of Muhammad Ali,” Wikipe-dia.org.

Roger Greenspun, “Screen: Jacobs’s ‘a.k.a. Cassius Clay’ Begins Run: Kiley Is Narrator of Evslin Script. . .,” New York Times, November 4, 1970.

“The New Movies,” New York Times, Novem-ber 15, 1970, p. D-7.

“The Fighters (1974),” American Film Institute Catalog, AFI.com.

“The Fighters” (1973), IMDB.com.

“The Fight (1974),” Directed By William Greaves, AA Film Fest, SI.EDU (Smithsonian).

“William Greaves,” Wikipedia.org.

Richard Brody, “The Muhammad Ali Doc-umentary That Gets to the Existential Heart of Boxing,” The New Yorker, June 13, 2016.

“Making The Movie: About William Greaves,” at: “Ralph Bunch, American Odyssey,” Amer-ican Experience, PBS.org.

“The Greatest (1977 film),” Wikipedia.org.

Kevin Thomas, “Ali Piles Up Points in ‘Great-est’,” Los Angeles Times, May 19, 1977, p. 14.

Vincent Canby, “The Greatest (1977) Ali’s Latest Victory Is ‘The Greatest’,” New York Times, May 21, 1977, p. 13.

Gene Siskel, “’The Greatest’ Isn’t the Greatest, But Takes an Entertaining Jab at it,” Chicago Tribune, May 23, 1977, Section 3, p. 9.

Arthur D. Murphy, “Film Reviews: The Greatest,” Variety, May 25, 1977.

“Gil Noble,” Wikipedia.org.

“When We Were Kings,” Wikipedia.org.

“Leon Gast,” Wikipedia.org.

“When We Were Kings (1996),” IMDB.com.

“The Rumble in the Jungle,” Wikipedia.org.

“Ali: An American Hero,” Wikipedia.org.

“Ali: An American Hero” (2000 TV Movie) and “User Reviews,” IMDB.com.

Phil Gallo, Review, “Ali: An American Hero,” Variety.com, August 30, 2000.

“Ali (Will Smith film),” Wikipedia.org.

Simon Robinson, “Making ‘Ali:’ Will Smith Inhabits the Role,” Time, December 15, 2001.

Richard Schickel, Cinema, “Film Review: An Epic Light on Its Feet,” Time, December 24, 2001.

“Lord of The Ring; Smith Makes the Greatest Movie,” Time (Europe, Middle East and Africa), January 28, 2002.

“An Epic Light on Its Feet; Film is Just the Greatest,” Time (Europe, Middle East and Africa), January 28, 2002.

“An American Original; Ali in History,” Time (Europe, Middle East and Africa), January 28, 2002.

“Thrilla in Maputo; The Power of Ali Lives On,” Time (Europe, Middle East and Africa), January 28, 2002.

Brian Raftery, “It’s Time to Revisit Ali, Will Smith’s Knockout Boxing Biopic,” Wired.com, June 6, 2016.

“Muhammad Ali: Made in Miami”(2008), IMDB.com.

“Facing Ali,” Wikipedia.org.

“When Ali Came to Ireland,” Wikipedia.org.

“Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight,” Wikipedia .org.

Howard L. Bingham and Max Wallace, Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight: Cassius Clay vs. The United States of America , February 2000, New York: M. Evans & Co., 271pp.

“Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight Trailer (HBO Films),” YouTube.com, August 27, 2013.

“Clay v. United States,” Wikipedia.org.

Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong, The Brethren: Inside The Supreme Court, 1979.

David E. Rosenbaum, “Ali Wins in Draft Case Appeal,” New York Times, June 29, 1971, p.1.

Hank Stuever, “HBO’s ‘Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight’: Interesting Legal Footwork, But No Knockouts,” Washington Post, October 3, 2013.

“Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight” (2013), User Reviews, IMDB.com.

“The Trials of Muhammad Ali,” Wikipedia .org.

Nicolas Rapold, “One of His Biggest Fights Was Outside of the Ring,” New York Times, August 22, 2013 (review of “The Trials of Muhammad Ali”).

Peter Sobczynski, “The Trials of Muhammad Ali Movie Review (2013),” RogerEbert.com.

“I Am Ali,” Wikipedia.org.

Michael Phillips, “Review: ‘I Am Ali’,” Chicago Tribune, October 9, 2014.

Chris Klimek, “‘I Am Ali’ Doesn’t Open Many New Doors, But It Offers Fresh Voices,” NPR.org, October 9, 2014.

Sheila Roberts, “I Am Ali: Director Clare Lewins on Her Muhammad Ali Documentary,” Collider.com, October 11, 2014.

Raqiyah Mays, “‘I Am Ali’ Celebrates Boxing’s Living Legend,” Ebony, October 20, 2014.

“What’s My Name: Muhammad Ali,” Trailer, Background & Extras, HBO.com.

“What’s My Name: Muhammad Ali,” Wiki-pedia.org.

Brian Lowry, “Muhammad Ali Doc ‘What’s My Name’ Is Good but Not Great,” CNN.com, May 14, 2019.

“Ali & Cavett: The Tale of the Tapes,” HBO.com.

Joe Leydon, “Film Review: ‘Ali & Cavett: The Tale of the Tapes’,” Variety.com, March 12, 2018.

Alex Williams, “Dick Cavett in the Digital Age. Stopping to Smell the Flowers with the Last Great Intellectual Talk-show Host,” New York Times, August 4, 2018.

“Dick Cavett Talks About The Time He Stepped In The Ring With Muhammad Ali,” YouTube.com.

Stephen Battaglio, “Playful. Proud. Provoca-tive. Meet Muhammad Ali, Late-Night Sensation,” Los Angeles Times, February 11, 2020.

Ed Cumming, “Ali & Cavett: The Tale of the Tapes Review: Optimistic Documentary Reminds Us of Boxer’s Huge Political Impact,” The Independent, June 1, 2020.

“One Night in Miami…,” Wikipedia.org.

“Blood Brothers: Malcolm X & Muhammad Ali,” Netflix.com, 2021.

Sheila O’Malley, “Film Review, Blood Brothers: Malcolm X & Muhammad Ali,” RogerEbert.com, September 9, 2021.

“Blood Brothers: Malcolm X & Muhammad Ali,” IMDB.com, 2021.

Lisa Kennedy, “‘Blood Brothers: Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali’ Review: Netflix Doc Pieces Together a Sundered Friendship,” Variety.com, September 10, 2021.

Peter Smith, “Conversion to Islam: Ali Shifted from Radical Sect to Inclusive Group,” Courier- ournal.com (Louisville, KY), June 4, 2016.

Tim Ott, “Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X: Inside Their Brief But Impactful Relation-ship,” Biography.com, September 2, 2021.

“Malcolm X: Make it Plain,” American Experience/ PBS.org, Aired, January 26, 1994.

Daniel Hautzinger, “Ken Burns, Sarah Burns, and David McMahon Take on Muhammad Ali,” WTTW.com (PBS-Chicago), June 4, 2021.

Caroline Framke, TV Review, “‘Muhammad Ali,’ A Thorough New Docuseries From Ken Burns and Company, Gives a Complex Icon His Due,” Variety,com, September 19, 2021.

Bob Costas Interviews Rasheda Ali and Filmmaker Ken Burns to Discuss the New Documentary about Muhammad Ali, “Back On the Record with Bob Costas,” HBO.com, Season 1 Episode 3, 2021.

Andrew L. John, “Muhammad Ali: Boxing Broadcaster Recalls Long Friendship,” The Desert Sun, June 9, 2016.

Cassius Clay, “I’m a Little Special,” Sports Illustrated, February 24, 1964, pp. 14-15.