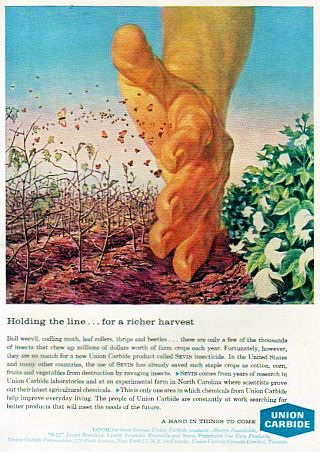

1963 Union Carbide ad titled, “Holding the Line...For a Richer Harvest,” touting its chemical insecticide, Sevin.

However, in this case, Union Carbide used a “giant hand” motif to capture attention and convey its industrial-sized prowess. And no doubt for some readers who viewed these ads, at one level the giant hands may well have conveyed a kind of almighty, “hand-of-God” type imagery. In fact, one observer of the Union Carbide ads noted: “The hand seems clearly intended to remind us of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, where Michelangelo depicted the hand of God bestowing life by touching Adam.”

The Union Carbide “giant hand” ads — and there were dozens of them in the series — typically explained how the company was wielding the powers of science and engineering, or touted the particular virtues of one or more products it was selling. Union Carbide was then ranked among the top 30 U.S. corporations on the Fortune 500 list, with mid-1960s annual revenues of about $1.5 billion or so.

One of Carbide’s giant hand ads, from 1963, shown at right, has the giant hand positioned in an agricultural field. One side of the field shows crop plants ravaged by disease and pestilence, and the other side, bountiful and productive – “protected” by the giant hand. The headline beneath the ad’s illustration reads: “Holding The Line …For a Richer Harvest.” The rest of the text explains:

Boll weevil, codling moth, leaf rollers, thrips and beetles . . . these are only a few of the thousands of insects that chew up millions of dollars worth of farm crops each year. Fortunately, however, they are no match for a new Union Carbide product called Sevin insecticide. In the United States and many other countries, the use of Sevin has already saved such staple crops as cotton, corn, fruits and vegetables from destruction by ravaging insects. You can now get Sevin insecticide for your own garden as part of the complete line of handy Eveready garden products that help you grow healthy vegetables and flowers. Sevin comes from years of research in Union Carbide laboratories and at an experimental farm in North Carolina where scientists prove out their latest agricultural chemicals. This is only one area in which chemicals from Union Carbide help improve everyday living. The people of Union Carbide are constantly at work searching for better products that will meet the needs of the future. ….A Hand in Things to Come. Union Carbide.

Union Carbide company logo with slogan, later years.

Carbaryl initially, was given a relatively clean bill of health in terms of its environmental and human toxicity. In fact, early on, the development of the carbamate insecticides was generally seen as something of a major breakthrough in pesticide chemistry, since the carbamates did not have the persistence of the chlorinated pesticides – which Rachel Carson would later single out in her seminal pesticide critique of 1962, Silent Spring. Still, carbaryl and Sevin, had toxic effects, not all of which were at first apparent. Carbaryl, the active ingredient in Sevin, is an inhibitor of the cholinesterase enzyme, found in nervous tissue, red blood cells, and plasma. That’s how it kills insects. But in the 1950s and early 1960s, environmental and health effects testing and analysis were very limited. And like other pesticides, carbaryl and Sevin would generate a long history of ongoing reviews by the U.S. EPA for health and environmental effects. Years later, in the early 2000s, the chemical would be classified as a likely human carcinogen by EPA based on animal feeding studies, though it is still used today. But in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Sevin was approved for use on hundreds of crops and other applications.

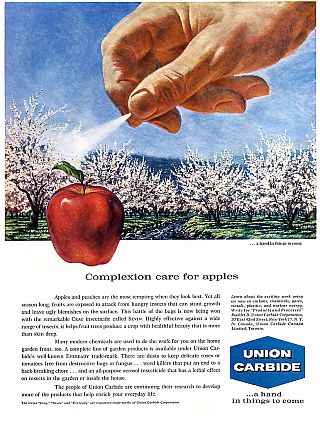

Union Carbide ad titled “Complexion Care for Apples,” touting the company’s Sevin insecticide for orchards.

Apples and peaches are the most tempting when they look best. Yet all season long fruits are exposed to attack from hungry insects that can stunt growth and leave ugly blemishes on the surface. This battle of the bugs is now being won with the remarkable Crag insecticide called Sevin. Highly effective against a wide range of insects, it helps fruit trees produce a crop with healthful beauty that is more than skin deep.

Many modern chemicals are used to do the work for you on the home garden front too. A complete line of garden products is available under Union Carbide’s well known Eveready trade-mark. There are dusts to keep delicate roses or tomatoes free from destructive bugs or fungus. . . weed killers that put an end to a back-breaking chore . . . and an all-purpose aerosol insecticide that had a lethal effect on insects in the garden or inside the house.

The people of Union Carbide are continuing their research to develop more of the products that help enrich your everyday life. Union Carbide. …A Hand in Things to Come.

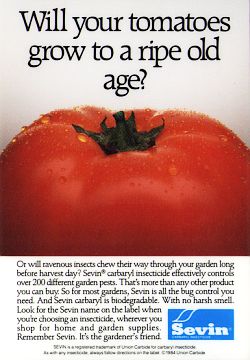

Carbide’s “giant hand” ads became part the “good-life-with-chemicals-and-plastics” mantra that was a cornerstone of chemical company growth and messaging that went on for decades from the end of WWII through the 1960s and beyond. Environmental and public health risks were not the primary concerns of Union Carbide and other chemical companies in those years. Rather, as these 1960s ads show, Sevin was touted by Carbide as a broad-spectrum insecticide, pushed to American farmers as a good thing. Sevin was also pitched for use in the home garden, and it was not uncommon to find home gardeners through the 1960s, and even in more recent decades, using Sevin dust on their tomatoes and other vegetables. Beyond American farmers and gardeners, Sevin was also proffered to third world countries as a savior for their insect-ravaged crops. Latin America was targeted first, then India.

A 1962 Union Carbide ad titled, “Science Helps Build a New India,” which appeared in 'National Geographic', among others.

By 1962, Union Carbide, in one of its “giant hand” ads (at left), was offering that view in a paternalistic, “Western-know-how- will-help-you” message titled, “Science Helps Build a New India.” The rest of the ad’s text ran as follows:

“Oxen working the fields . . . the eternal river Ganges . . . jeweled elephants on parade. Today these symbols of ancient India exist side by side with a new sight – modern industry. India has developed bold new plans to build its economy and bring the promise of a bright future to its more than 400,000,000 people. But India needs the technical knowledge of the western world. For example, working with Indian engineers and technicians, Union Carbide recently made available its vast scientific resources to help build a major chemicals and plastics plant near Bombay. Throughout the free world, Union Carbide has been actively engaged in building plants for the manufacture of chemicals, plastics, carbons, gases, and metals. The people of Union Carbide welcome the opportunity to use their knowledge and skills in partnership with the citizens of so many great countries.” The ad ends with the sign off: “A Hand in Things To Come / Union Carbide.”

Union Carbide India, Ltd. plant at Bhopal, India. |

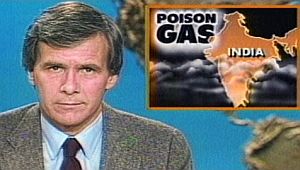

Dec 3rd, 1984: Screenshot of “NBC Nightly News” TV program with Tom Brokaw reporting on Bhopal gas leak. |

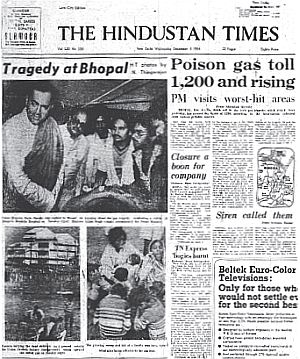

December 5th 1984 edition of The Hindustan Times of India with early reporting on the Bhopal gas leak disaster. |

The Bhopal Plant

India by the 1960s had begun to embrace the promise of Green Revolution agriculture – a regimen that used new wheat varieties, heavy fertilization, and chemical pesticides. In 1969 in central India, a few miles from Bhopal, a city of about 900,000 people, a new pesticide plant was built. That year, Union Carbide India, Ltd. (UCIL) — 50.9 percent owned by the Union Carbide Corp.(U.S.) — began producing Sevin and another pesticide, Temik, an aldicarb pesticide.

In manufacturing these pesticides, an intermediate chemical ingredient named methyl isocyanate, or MIC, was used. For the first decade or so, the Bhopal plant imported MIC from a Union Carbide “sister plant” located in Institute, West Virginia.

By the late 1970s, however, the Bhopal plant added its own MIC production unit, with engineering and design based on Carbide’s West Virginia plant.

Normally, during the process of producing the pesticides, MIC, a dangerous gas, was vented and passed through a sodium hydroxide scrubber and flare towers to prevent any problems. But on December 2nd, 1984, something went wrong at the Bhopal plant.

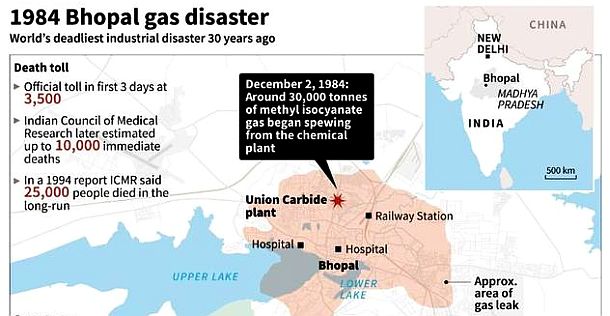

At 11:30 p.m. that night, workers at the Bhopal plant, their eyes tearing and burning, informed their supervisor they had detected a gas release. By 12:45 a.m. a rapid pressure increase occurred inside one of the MIC storage tanks, which opened the safety relief valve, releasing the dangerous methyl isocyanate into the atmosphere. In all, some 40 tons of the gas were released.

Twice as heavy as air, methyl isocyanate remained close to the ground as an escaping gas cloud as it left the plant, rolling southward on light winds. The low-lying, ground-hugging gas cloud was heading toward the eastern flank of a sleeping Bhopal.

MIC is a highly poisonous gas, capable of reacting violently with many substances, including water and some metals. It is also particularly lethal to the eyes and respiratory system.

On December 3rd, 1984, as the gas left the plant, it first hit densely-populated squatter settlements near the plant containing some of Bhopal’s poorest citizens. Thousands were killed in their sleep or as they fled in terror.

The gas poured out of the plant for nearly two hours, spreading eight kilometers downwind over the city. Hospitals were overwhelmed in the hours and days that followed.“No one is counting the numbers any longer,” reported chemical engineer and journalist Praful Bidwai at the Hamidia Hospital three days after the gas release. “People are dying like flies. They are brought in, their chests heaving violently, their limbs trembling, their eyes blinking from the photophobia. It will kill them in a few hours, more usually minutes.”

There were more than 500,000 people in the path of the Union Carbide MIC gas leak at Bhopal. At least 3,000 people are thought to have perished in the first 24 hours. Thousands more died within two weeks. And over the years since the disaster, thousands more succumbed as gas-related diseases took their toll. Additionally, many thousands more were injured or were left with debilitating life-long conditions of one sort or another — 558,125 with some kind of injury by one count.

A 2014 report in Mother Jones magazine, quotes a health clinic spokesperson for Bhopal Medical Appeal, noting that: “An estimated 120,000 to 150,000 survivors still struggle with serious medical conditions including nerve damage, growth problems, gynecological disorders, respiratory issues, birth defects, and elevated rates of cancer and tuberculosis.” However the grim toll of this tragedy is counted, Bhopal remains the worst industrial accident in history.

Portion of a graphic showing map of 1984 Bhopal gas release and incorporating various estimates of those killed in the immediate aftermath of the incident and longer term. AFP / Source: India CSE/ICMR

The repercussions of the disaster would stretch over the next 30 years, and as of this writing they continue. A wide variety of social justice, victims compensation, environmental and other organizations have worked for years to bring fair compensation to the people of Bhopal and its region, among these, the International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal. Union Carbide and its successors were taken to court and brought before tribunals multiple times and in varying U.S. and Indian jurisdictions.

Dan Kurzman’s 1987 book on Bhopal, “A Killing Wind,” was one of a number of books written on the tragedy and its aftermath. Click for copy.

In October 2003, U.S. Congressman Frank Pallone (D-NJ) and eight other members of Congress filed an amicus brief on behalf of about 20,000 victims of the 1984 Bhopal disaster. The brief, initiated by Pallone— a co-founder of the Congressional Caucus on India and Indian Americans— came in response to a March 2003 decision by a U.S. District Judge in New York who dismissed all claims against Dow Chemical (although Bhopal victims appealed). Pallone and his colleagues sent a 23-page brief in the appeal case. It urged the court to hold Dow Chemical responsible. “There is strong support in Congress for holding those responsible for this horrific tragedy accountable for their actions,” said Pallone at the time. “It is unacceptable to allow an American company not only the opportunity to exploit international borders and legal jurisdictions, but also the ability to evade civil and criminal liability for environmental pollution and abuses committed overseas.”

In November 2014, at the 30th anniversary of the Bhopal disaster, the film, “A Prayer for Rain,” starring Martin Sheen, was released. Click for film.

Back in the mid-1980s, meanwhile, one of the highlighted revelations driven home by the Bhopal incident was that the way pesticide and other chemical products were made – that is, the chemical ingredients and processes used in their manufacture – could be quite dangerous and toxic to workers and nearby communities. Chemical plant safety, in other words, was spotlighted by the Bhopal disaster in a much bigger way than it had been previously. And the risks to public safety weren’t limited to foreign locations with little regulation. In fact, in the U.S. not long after the Bhopal disaster, there was a less serious but no less worrisome incident at a Union Carbide plant that also handled methyl isocyanate.

West Virginia Leak

In the mid-1980s, Union Carbide operated a chemical plant located at Institute, West Virginia, where it also produced methyl isocyanate (MIC) – the same gas that had savaged Bhopal. Carbide officials, however—especially in the aftermath of Bhopal—had promised to focus on safety at all of their facilities. Yet federal investigators in 1985 soon found serious problems at Institute—namely, 190 chemical leaks from the MIC plant in a five-year period. Still, company Chairman Warren Anderson then assured the public that Carbide had gone through the complex “with a fine tooth comb” and had determined the plant was “safe to run.” The company poured millions into the Institute plant to demonstrate its commitment to safety. But at the very place where the company was making its supposed best effort, another mishap occurred.

Wire service stories on Union Carbide’s August 1985 gas leak in West Virginia appeared in various U.S. newspapers.

Given the Bhopal incident, and revelations that American plants weren’t all that safe either, Congress was spurred to action, and soon moved to adopt tougher regulation. The 1986 Emergency Planning and Community Right to Know Act was adopted, establishing the Toxic Release Inventory, which improved citizen access to toxic chemical information in their own communities. EPA reports made clear that the U.S. chemical industry had the capacity and the potential, with the right set of circumstances, to have Bhopal-scale or worse chemical disasters. It also helped to improve state and local emergency planning. And for the next several years, chemical plant safety and toxic release issues remained on the agenda as Congress considered the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990. During that debate, EPA reports made clear that the U.S. chemical industry had the capacity and the potential, with the right set of circumstances, to have Bhopal-scale or worse chemical disasters. More emphasis was placed on chemical plant safety at EPA and OSHA, and new programs were adopted. EPA was authorized to develop its Risk Management Program Rule for protection of the public, and OSHA to develop its Process Safety Management Standard to protect workers. The Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 also established the independent U.S. Chemical Safety Board, which since its creation, has become an important investigative entity, issuing hundreds of accident investigation reports and recommendations for improved chemical plant safety. Still, to this day, many find that national chemical safety oversight is lacking, fraught with basis data gaps, and lacking in meaningful funding.

Sevin Survives

One of the 1984 ads for Union Carbide’s Sevin pesticide by the ad agency Ogilvy & Mather.

Close up shot of a front panel from a Garden Tech Sevin product in recent years.

Since then, EPA has made more reviews of carbaryl and Sevin and more restrictions have come on the chemical. In 2003, EPA classified carbaryl as a likely human carcinogen. It is also potentially toxic to the human nervous system, can cause nausea, dizziness, confusion and, at high exposures, respiratory paralysis and death. Young children are particularly vulnerable to carbaryl and other pesticides because their bodies and brains are still developing. In the environment, since it is a broad-spectrum insecticide, carbaryl can kill beneficial insects like honeybees and other pollinators. And when this chemical runs off farms and lawns it can contaminate streams and rivers, where it is toxic to aquatic animals and fish. Yet, at this writing, Sevin and carbaryl are still used on a wide variety of farm and orchard crops including, apples, pecans, grapes, alfalfa, oranges and corn. as well as lawns and gardens. But EPA has been tightening its restrictions. In October 2009, the agency announced that carbaryl will no longer be allowed for use in flea collars. The environmental organization, NRDC, the Natural Resources Defense Council, has called for a total ban on the chemical. “The surest way to protect the American public at large is to ban the use of carbaryl entirely,” says NRDC on its “Smarter Living” page profiling carbaryl. Sevin/carbaryl, meanwhile, has had a product lifetime of more than 50 years, which shows that once chemicals are approved for use, getting them removed from the market is nearly impossible.

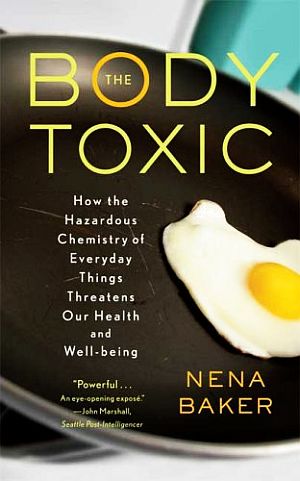

“The Body Toxic” by Nena Baker, one of a number of books to probe the dangers of “everyday chemistry.” Click for copy.

As for Union Carbide’s “giant hand” ads of the 1950s and 1960s – and there was an extensive series of these covering a gamut of Carbide products and industries – they went the way of over-done industrial hype and eventually faded from the advertising pages. However, these Union Carbide ads – among others from the chemical industry in those years – helped create and embed a “chemicals-are-good-for-you” culture, along with the notion that these substances were somehow the handmaidens of progress, vital to the economy, and above reproach or challenge. Rather, the “giant hand” needed today is one of safety assurance from the government, strict chemical oversight, and no chemical harm.

See also at this website, “Power in the Pen,” the story of Rachel Carson’s 1962 best-selling book, Silent Spring, which rocked the chemical industry and helped spur the modern day environmental movement. Additional stories on business & environment issues can be found at the “Environmental History” topics page; the “Business & Money” category page; and the “Politics & Culture” page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you see here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 4 May 2015

Last Update: 5 April 2019

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “…A Richer Harvest: Union Carbide Ads, 1960s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, May 4, 2015.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“Holding the Line…For a Richer Harvest” (Union Carbide advertisement), The Illinois Technograph, April 1963, p. 2.

Union Carbide Corporation, Company Profile, Hoover’s Handbook of American Companies, 1996, Austin, TX: The Reference Press, Inc.,.

Milt Moskowitz, Michael Katz, and Robert Levering, Everybody’s Business, Harper & Row: San Francisco, 1990, pp. 526–27.

David Dembo, Ward Morehouse, Lucinda Wykle, Abuse of Power: Social Performance of Multinational Corporations: The Case of Union Carbide, New York: New Horizons Press, 1990.

“Complexion Care for Apples” (Union Carbide advertisement), Torrance Press (newspaper, Torrance, CA), Thursday, August 15, I957, p. 15.

Rajiv Desai, “An Ill Wind: For The People Of Once-prosperous Bhopal, The Horror Of History`s Worst Industrial Disaster May Never End,” ChicagoTribune.com, November 30, 1986.

Dhiren Bhagat, “A Night in Hell,” Sunday Observer, reprinted in Bhopal: Industrial Genocide?, Arena Press, March 1985, p. 23, and Praful Bidwai, “The Poisoned City—Diary From Bhopal,” Times of India, December 16, 1984, both cited by Russell Mokhiber in Corporate Crime and Violence, San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1988.

“Bhopal Disaster,” Wikipedia.org.

Jackson B. Browning (Retired Vice President, Health, Safety, and Environmental Programs

Union Carbide Corporation) “Union Carbide: Disaster at Bhopal,” 1993.

Amy Waldman, “Bhopal Seethes, Pained and Poor 18 years Later,” New York Times, September 21, 2002, p. A-3.

U.S. Chemical Safety & Hazard Investigation Board, “Bhopal Disaster Spurs U.S. Industry, Legislative Action,” Electronic Reading Room, ChemSafety.org, September 1999.

Scott Baldauf, “Bhopal Gas Tragedy Lives On, 20 Years Later,” Christian Science Monitor, May 4, 2004.

Jack Doyle, Trespass Against Us: Dow Chemical & The Toxic Century, Monroe, Maine: Common Courage Press/Environ- mental Health Fund, Boston, MA, 2004.

Edward Broughton, “The Bhopal Disaster and its Aftermath: A Review,” Environmental Health (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), Published online May 10, 2005.

Mick Brown, “Bhopal Gas Disaster’s Legacy Lives on 25 Years Later,” The Telegraph, August 6, 2009.

Alex Masi, Sanjay Verma, Maddie Oatman “Photos: Living in the Shadow of the Bhopal Chemical Disaster,” Mother Jones, June 2, 2014.

“WikiLeaks: Dow Monitored Bhopal Activists,” Wall Street Journal/India Real Time, February 29, 2012.

Jon Mcclure, Daniel Lathrop and Matt Jacob, “90% of Chemical Accident Data Wrong; Gaps, Inaccuracies Erode Ability to Prevent the Next Catastrophe,” Dallas Morning News, August 25, 2013.

United Press International, “Union Carbide Says U.S. Must `Live With Leaks`,” February 20, 1985.

Karen Tumulty, “Scores Hurt by Leaking Chemicals : Faulty Valve Cited at Union Carbide’s West Virginia Plant,” Los Angeles Times, August 12, 1985.

Anndee Hochman, “Faulty Valve Blamed For Leak at Second Union Carbide Plant,” Washington Post, August 15, 1985, p. A-3.

Stuart Diamond, “Credibility a Casualty in West Virginia,” New York Times, August 18, 1985, p. 1-E.

Associated Press, “Carbide Details Poison Leak,” Washington Post, August 24, 1985, p. A-5.

W. Joseph Campbell, “Toxic Leak Still Haunts W. Va., Despite Carbide’s Efforts,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 27, 1985.

Philip Shabecoff, “Union Carbide Agrees to Pay $408,500 Fine for Safety Violations,” New York Times, July 25, 1987, p. 8.

Union Carbide Ag/Consumer Pesticide Brands, Agency: Ogilvy & Mather/Atlanta, behance.net.

Warren Schultz, Jr.,”The Trouble with Carbaryl,” Organic Gardening, October 1984.

Insecticide Fact Sheet, Carbaryl, Journal of Pesticide Reform, Summer 2005, Vol. 25, No. 2.

Union Carbide Corporation History, FundingUniverse.com.

“Carbaryl,” ChemicalWatchFactsheet, Beyond Pesticides.org, Updated March 2001.

Carbaryl /Chemical Index, ”Smarter Living,” Natural Resources Defense Council.

U.S EPA, Amended Carbaryl RED, August 2008 (PDF)

U.S. EPA, Carbaryl IRED Facts, October 2004 (PDF)

“Carbaryl” (General Fact Sheet), National Pesticide Information Center, (NPIC is sponsored cooperatively by Oregon State University and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency).

________________________________________________