One of the logos that appeared on television screens in the 1950s at the opening of the “I Love Lucy” show.

Broadcast on the CBS television network in its early years, from October 1951 to April 1957, I Love Lucy had more total share of viewers than any other show on television. It was either the No. 1, No. 2, or No. 3 show during that period, garnering audiences of between 48 and 67 percent of homes with television sets.

By April 7, 1952, some 10.6 million households – roughly 30-to-40 million viewers – were tuning in to I Love Lucy each week. It was the first time in history that a television show had reached that many people. Watching I Love Lucy in the 1950s became a weekly ritual for much of America.

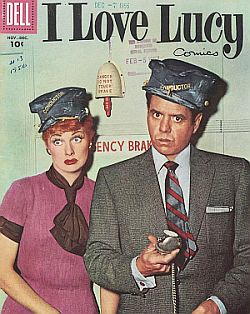

Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz played “Lucy & Ricky Ricardo” on the CBS TV show, “I Love Lucy.”

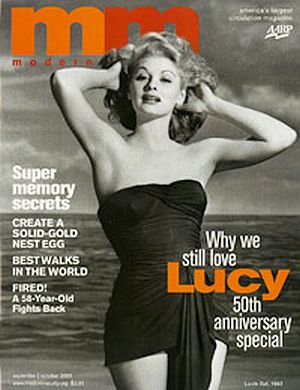

Young Lucille Ball as model and actress.

In the 1930s, she decided to try film and moved to Hollywood. There she became a B-grade movie actress, appearing in several films. In 1933, she was selected as a “Goldwyn Girl” for the film Roman Scandals, and later that year, signed with Columbia, called RKO in 1935. In 1940, she met and married Cuban bandleader Desi Arnaz while making the film version of the Rodgers & Hart stage hit, Too Many Girls. She continued acting with MGM through 1946. With her film career ending, she joined CBS radio in 1947 for a role in the situation comedy My Favorite Husband. There she was cast a somewhat wacky wife to a conservative Midwest banker husband played by Richard Denning. Then in 1951, CBS asked that Lucy explore the possibility of a weekly show similar to My Favorite Husband, but broadcast on the hot new medium, television. She was 40 years old at the time.

Other radio performers had gone over to television by then, such as Arthur Godfrey and Jack Benny, but the shows were still new. Corporate advertisers, however, were there from the start, sponsoring some of the earliest shows. In June 1948, Ed Sullivan’s Sunday evening show was sponsored by Lincoln Mercury; George Burns and Gracie Allen’s show had B.F. Goodrich; and in September 1948, Milton Berle’s Texaco Star Theater began its popular run with the Texaco oil company as it prime sponsor.

Lucille Ball worked at CBS radio in the late 1940s where she did the program “My Favorite Husband” which she used to help frame the “I Love Lucy” TV show.

Lucy’s TV Plan

Lucille Ball, as she was working on the idea for a CBS-TV show in 1951, thought she could use her radio show sitcom as a framework for the new TV show. However, she also proposed a new twist: she wanted her real life husband, Desi Arnaz, a Cuban band leader, to play her TV husband.

Studio brass worried that American audiences would not find such a “mixed marriage” to be believable, and were concerned about Arnaz’s heavy Cuban accent. Lucy argued that Desi was her real husband, and therefore a viable marriage as far as she saw it. She also believed privately that the couple’s real marriage would be seen favorably by viewers and add to show’s interest.

During the summer of 1950, Lucy and Desi went on tour performing before live audiences to prove to CBS that Desi would be believable as her husband. Early in 1951 they produced a film pilot for the series with $5,000 of their own money.

Nov 19, 1951: In “I Love Lucy” episode "The Audition," Lucy appears at Ricky’s stage act in disguise as the dim professor clown with an uncooperative cello.

In building the show’s framework, Lucy wanted her character to appeal to average viewers. She did not want to be cast as a Hollywood star, but rather, a housewife who wanted to be a star. In fact, that became an oft-repeated theme in many shows, with Lucy always scheming in some way to get on stage or prove she had talent.

In the sitcom, Lucy Ricardo became the somewhat wacky wife, who in her escapades always appeared to be making life difficult for her loving but often flustered husband, Ricky, a Cuban bandleader at the Tropicana Club somewhere in Manhattan.

Lucy was constantly trying to prove to Ricky she could be in show business too, and with her neighbor and friend, Ethel Mertz, would concoct crazy schemes of one sort or another that often led to riotous slapstick outcomes.

Ricky, on the other hand, just wanted her to be a simple housewife. But as often turned out, he and neighbor Fred Mertz, would wind up saving Lucy and Ethel from some near-catastrophic situation. The first show aired on October 15, 1951.

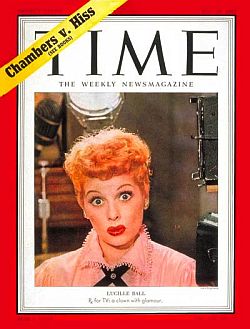

May 26, 1952: Time cover says Lucy is “Rx for TV.”

“Lucille Ball was destined for television, where her slapstick talents could be properly appreciated. Lucy had a marvelous comic voice, but, like [Milton] Berle, she was primarily a visual comedienne. She was just wacky and naive enough to generate sympathy rather than irritation.”

And Desi Arnaz proved all the doubting CBS executives wrong as well, becoming the perfect foil for Lucy. Desi had good comedic timing, an expressive face, and offered just the right amount of fluster as husband Ricky. His mispronounced and “Latinized” words added to the comedy. The show’s skits appealed to a wide variety of age groups with believable dilemmas similar to those encountered by married couples in their everyday lives. Within four months of its debut, I Love Lucy was the No. 1 show in New York, and the national audience soon followed.

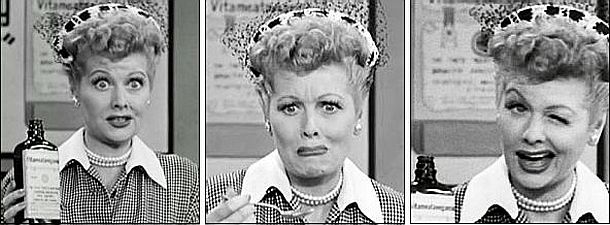

What soon became apparent as the show began its run and the skits poured out, was that Lucille Ball was a very talented comedienne, possessed of timing, facial, and body language skills that made her a superb comic. She was a master of physical and slapstick comedy, and her chief asset became her incredibly expressive face; a face that could dominate a scene and say all that needed to be said without uttering a word. Some samples follow below.

Lady of 1,000 Faces

Master Comedienne of Expression

In fact, Lucille Ball seemed to make her face “fit” every character she inhabited, and she used her facial expressions naturally and seamlessly, along with complimenting voice flexion and body movements for maximum effect. Lucy was an attractive woman, endowed with large eyes and a large mouth, and in her performances she put these features to good and sometimes wildly contorted use in an ever-expanding array of “Lucy looks.” She could be a scene stealer; sometimes single-handedly capturing the moment with her facial expression or body pose.

Lucy Tops TV

January 19, 1953: Newsweek, “Lucille Ball: Who Doesn’t Love Lucy?”

In 1952, when Lucy became pregnant in real life, she argued for working her pregnancy into the script of the show, which CBS and Philip Morris reluctantly agreed to after some worry about public reaction. In fact, the public followed each episode with more interest, it seemed, leading up to the January 19, 1953 episode when – in real life and on the TV show – Lucy gave birth to a boy, named “Little Ricky” on the show. In real life, her new baby was her second child, Desi Arnaz, Jr. An estimated 68 percent of television sets that night were tuned to I Love Lucy, meaning that about 44 million people were watching. “That was twice the number who watched the inauguration of Dwight Eisenhower the next day,” observed David Halberstam. Lucy and her new baby, meanwhile, also made the covers of several magazines, including Life and Look, the popular mainstream picture magazines of their day.

April 1953: Lucy, Desi, their new baby and daughter Lucie featured as “TV’s First Family” on Life cover. Click for copy.

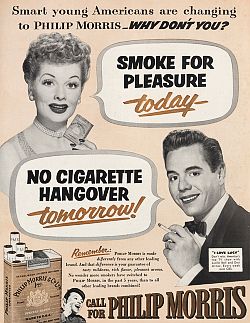

Philip Morris, in fact, was quite satisfied with its part of the deal. In describing the contract with Lucy and Desi, as reported in 1985 by Bart Andrews in The ‘I Love Lucy’ Book, the president of Philip Morris explained: “This show is the all-time phenomenon of the entertainment business. On a strictly dollars-and-cents basis, it is twice as effective as the average nighttime television show in conveying our advertising message to the public. . . . [I]t is probably one of, if not the most efficient advertising buys in the entire country. In addition, we derive many supplementary merchandising and publicity benefits from the show. As you can see, we love ‘Lucy.’”

|

“Lucy & Tobacco”  1953: Sample magazine ad featuring Lucille Ball pitching Philip Morris cigarettes. In the very first episode, aired on October 15, 1951, the cigarette pitch came first, before the show even started. It opened with a Philip Morris “narrator” positioned on the show’s stage set, standing in middle of the Ricardo living room where the show’s story would unfold. The Philip Morris narrator then began his pitch to the TV audience: “Good evening and welcome. In a moment we’ll look in on Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. But before we do that, may I ask you a very personal question? The question is simply this – do you inhale? Well, I do. And chances are you do, too. And because you inhale you’re better off–much better off–smoking Philip Morris and for good reason. You see, Philip Morris is the one cigarette proved definitely less irritating, definitely milder than any other leading brand. That’s why when you inhale you’re better off smoking Philip Morris . . . . And now Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz in I Love Lucy.”  Lucy & Ricky cartoon characters. “By standing in the living room set, the announcer places himself in the fictional world of the Ricardos, greeting and welcoming the viewer as a guest visiting the Ricardo home, yet his words move out of the fictional set and into ‘your’ living room, as he first allies himself with the viewer (i.e., ‘In a moment, we’ll look in’) and then hails the viewer directly with…implied dialogue made familiar by radio advertising (‘may I ask you a very personal question?’).”  Lucy & Ricky stick figures clowning with a cigarette pack. That call would also be heard on some of the I Love Lucy show openings and closings. In addition, on the show’s opening and closing credit scrolls – as well as ads run during the show – the cartoon-type stick figures of Lucy, Desi, and bellhop would appear, holding packs of cigarettes or otherwise plugging Philip Morris.  Lucy & Desi appear in 1952 Philip Morris ad. |

TV, CBS On Rise

TV screenshot of a 1950s CBS network logo.

CBS, meanwhile, was still new in the TV business. It had begun providing a full prime time schedule for stations in 1948, many of which had been carried over in whole or part from CBS radio programs, as with Lucy’s radio show, My Favorite Husband. But with television, CBS became a much greater power, for its early shows like I Love Lucy began to dominate the airwaves and ratings, and that meant more money, as David Halberstam reported in his book, The Powers that Be:

…For the first twenty five years of its history the net income of CBS had averaged $4 or $5 million a year. Those were essentially radio years. Then television arrived. In 1953, television reached 21 million American homes and CBS income after taxes reached $8.9 million; by 1954, the year that CBS, by virtue of television, became the largest advertising medium in the world, the net income was $11.4 million; By the end of the 1956-1957 TV season, CBS controlled nine of the top ten slots, with I Love Lucy at the top.by 1957, 42 million homes had television sets and the profits after taxes reached $22.2 million. It was a constantly ascending curve… In the first decade of national television, CBS dominated…

By the end of the 1956-1957 television season, the network controlled nine of the “top ten” slots in terms of ratings, with I Love Lucy at the top, followed by other CBS shows such as The Ed Sullivan Show, General Electric Theater, The $64,000 Question, December Bride, and others. CBS profits rose to about $50 million by 1965, and by the mid-1970s, they were at $100 million annually. The CBS network would retain its Top Ten TV show dominance through much of the 1960s, until the rise of ABC in the mid-1970s. But back in the 1950s, there were some perilous times for the entertainment industry and emerging icons such as Lucille Ball, as the politics of that era turned scary.

“Reds”

Headline from Sept 11th, 1953 “Los Angeles Herald Express” charges: “Lucille Ball Was Red in 1936."

In 1953, Lucille Ball was subpoenaed by the House Committee on Un-American Activities because on a 1936 voter registration card on which she had declared her intent to vote for Communist Party candidates. On September 4th, 1953, Lucy testified before a congressional panel in a closed-door session in Los Angeles. She would explain that the registration had come about at the insistence of her socialist grandfather. She had also supported American political candidates since 1936. In 1944 she was seen at an FDR fundraiser as a prominent supporter, and in 1952 she voted for President Eisenhower. While she was questioned extensively by the Congressional committee in September 1953 about the 1936 card and some other activities – noting then that she had little interest in politics herself – she was cleared of all suspicion. Still, her appearance had been private and not reported in the press – at least not until the story came out about a week later.

Sept 12th, 1953: Los Angeles Times photo shows Lucille Ball & Desi Arnaz meeting with reporters following Lucy’s Congressional testimony on communism. |

Sept 12th, 1953: Los Angeles Times photo shows Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz meeting with the press in the back yard of their home. Desi is holding their dog, Pinto. |

Following her testimony, Lucy and Ricky had been on edge about the allegations. According to reports, two nights after her closed-door private session in Los Angeles with the House Un-American Activities Committee, she was at home on a Sunday evening going over her latest I Love Lucy script while listening to Walter Winchell’s popular radio program. During his broadcast, Winchell mentioned a “blind” item, stating that “the top television comedienne has been confronted with her membership in the Communist party.” The following day, in some newspapers, Walter Winchell’s syndicated column reiterated the news. On Friday morning, September 11th – also the first day of shooting the third season of I Love Lucy – the front page of the Los Angeles Herald Express featured a photo of Lucy and her 1936 Communist registration card, with the headline “Lucille Ball Named Red.” While Lucy was rehearsing, Desi met with CBS and MGM executives who assured him they were behind he and Lucy. Sponsor Phillip Morris, however, was another story. If the plug was pulled on I Love Lucy not only would Lucille Ball’s career be ruined, but hundreds of Desilu employees would be out of a job.

On September 12th, 1953, after a transcript of Lucy’s appearance before a private session of the House Un-American Activities Committee was released, she and Desi met with press at their Chatsworth, California home. Lucy told the assembled group of half dozen or so reporters that she was confident the current stir over her registration as a Communist in 1936 would not damage her career. “Hurt me?” she said, according to a Los Angels Times report. “I have more faith in the American people than that. I think any time you give the American people the truth they’re with you.” Testimony by Lucy’s mother and brother also corroborated the fact that they, too, had registered communist to please the grandfather.

On September 13th, 1953 the Los Angeles Times ran a front page story reporting on Lucy and Desi’s reaction to the release of Lucy’s testimony, a story which included the two photos shown above. Lucy and Desi expressed relief it was now in the open. By September 14, 1953, the Los Angeles Times was reporting that Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz were “comforted by stacks of telegrams from well-wishers” supporting them regarding the charges.

Yet, at the filming of the 1953-54 season I Love Lucy premiere, Desi Arnaz, who typically warmed up the studio audience before they performed their episode, gave a serious speech denouncing communism and labeling the rumors about Lucy as lies. The audience cheered. He ended his remarks that night by introducing his wife: “And now, I want you to meet my favorite wife” (a play on Ball’s successful 1940s radio show, My Favorite Husband) “my favorite redhead – in fact, that’s the only thing red about her and even that’s not legitimate – Lucille Ball!” Although Lucy was cleared of any official suspicion, the FBI reportedly still kept a file on her.

Ricky & Lucy discuss some mysteriously discovered cash in a 1950s episode of “I Love Lucy.” |

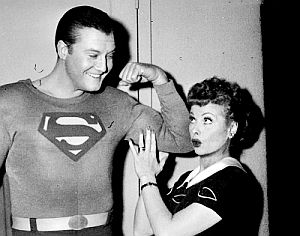

Nov 1956: Lucy with Superman (George Reeves) who starred in his own 1950s series, “The Adventures of Superman.” |

1954 Emmy Awards: From left: Vivian Vance, Desi Arnaz, William Frawley, and Lucille Ball celebrate after collecting at least two of their awards. |

Lucy’s Success

I Love Lucy, meanwhile, went on to continue its stellar performance in TV ratings with some 159 episodes produced over seven years – finishing as the No. 1 or No. 2 rated show for most of those years. Among some of the more famous I Love Lucy episodes during the 1951-1957 period were: “The Audition” (Nov 1951), when Lucy fills in as a clown during a Ricky TV audition; “Lucy Does a TV Commercial” (May 1952), when Lucy is hired as the ‘Vitameatavegamin’ girl pitching a special patent-medicine vitamin product; “Job Switching” (Sept 1952), when Lucy and Ethel trade places with this husbands who do house work while they take jobs at a candy factory where they confront a very speedy chocolate production line; “L.A. At Last!” (Feb 1955) a show with an appearance of famous actor William Holden; another on May 9th, 1955 with “Harpo Marx;” and a classic from January 14th, 1957, “Lucy and Superman,” when Lucy tries to get Superman, played by George Reeves, to attend a birthday party for her son, Little Ricky.

Of course, I Love Lucy wasn’t the only family based sitcom of the 1950s and 1960s. Among others in that era, for example, were The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show (1950-58), The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet (1952-66), and The Danny Thomas Show (1953-64). But it was the Lucy character and Lucille Ball who became, for millions, two of the nation’s best known figures of the 1950s and 1960s. Yet, in terms of the social impact of the “Lucy” character, especially for women, there were varying interpretations – whether she was simply a bumbling, domesticated idiot, or something a bit deeper; something closer to a rebellious, though comic, non-conformer. One take on that latter view is offered below by Christopher Anderson writing for the Museum of Broadcast Communications:

…It is possible to see I Love Lucy as a conservative comedy in which each episode teaches Lucy not to question the social order. In a series that corresponded roughly to their real lives, it is notable that Desi played a character very much like himself, while Lucy had to sublimate her professional identity as a performer and pretend to be a mere housewife. The casting decision seems to mirror the dynamic of the series; both Lucy Ricardo and Lucille Ball are domesticated, shoehorned into an inappropriate and confining role. But this apparent act of suppression actually gives the series its manic and liberating energy. In being asked to play a proper housewife, Lucille Ball was a tornado in a bottle, an irrepressible force of nature, a rattling, whirling blast of energy just waiting to explode. The true force of each episode lies not in the indifferent resolution, the half-hearted return to the status quo, but in Lucy’s burst of rebellious energy that sends each episode spinning into chaos. Lucy Ricardo’s attempts at rebellion are usually sabotaged by her own incompetence, but Lucille Ball’s virtuosity as a performer perversely undermines the narrative’s explicit message, creating a tension which cannot be resolved. Viewed from this perspective, the tranquil status quo that begins and ends each episode is less an act of submission than a sly joke; the chaos in between reveals the folly of ever trying to contain Lucy.

Magazine ad for an “I Love Lucy” bedroom suite.

“Live Like Lucy”

I Love Lucy also generated its own little economy. In addition to helping the tobacco industry make millions, Lucy and Desi would soon realize their show was a veritable pot of gold in other ways. They had already established a TV production company, first created in 1951 to produce the vaudeville act they used to convince CBS they were a viable pair for a TV show. This company would become known variously as Desilu Studios or Desilu Productions (“Desilu” formed by combining Desi and Lucy). Desilu would produce the I Love Lucy shows. Later it would also become the owner and/or producer of other hit TV shows like Star Trek, Mission Impossible, and others. More on Desilu a bit later.

But during the 1950s, I Love Lucy also spawned a huge merchandising business. Millions of I Love Lucy viewers wanted to be like Lucy and Ricky, and have the things that appeared in the TV show. Academic researchers, historians and writers such as Bart Andrews, author of The I Love Lucy Book, and Lori Landay of the University of Pennsylvania, have documented much of the merchandising that surrounded the show. Beginning in October 1952, for example, there were 2,800 retail outlets for Lucille Ball dresses, blouses, sweaters, aprons, pajamas and more, and also Desi Arnaz smoking jackets and robes.

In one month in late-1952, 30,000 Lucy dresses were sold, along with 32,000 heart-adorned aprons. Lucy and Ricky pajamas sold out in two weeks. There was also a line of dolls produced. During one Christmas rush, 85,000 Lucy dolls were sold. Even Lucy and Ricky bedroom suites were sold. In fact, in January 1953, the first month of selling the bedroom suites, $500,000 in sales were reported in two days. There were also Desi sport shirts and denims, Lucy lingerie and costume jewelry, desk and chair sets, I Love Lucy albums, sheet music, coloring books, and comic books.After the “Ricardo” and Ball-Arnaz babies were born in January 1953, the show spawned merchandising tie-ins that exceeded $50 million. Desilu also received five percent of the gross earnings of any products the stars endorsed. By 1957, according to Parade magazine, Lucy and Desi were worth an estimated $25 million, or roughly $100 million in 2013 dollars.

Although I Love Lucy, the original series, ended in 1957 – as the couple had become weary of the weekly production grind – the show went out on top, still ranked No. 1. And in subsequent years, the Lucy character would appear again and again, not only in rebroadcasts of older I Love Lucy shows, but also in new TV series that ran in the 1960s, 1970s and also briefly in 1986. More on those later.

Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz in their respective Desilu Studios directors chairs, circa 1950s.

The Rise of Desilu

During the years that I Love Lucy ran, the Desilu Studios became the fastest rising production company in television. Initially formed by Lucy and Desi in 1951 with some $5,000, in just six years’ time it would grow from a dozen employees to some 800. Using the income generated by the success of I Love Lucy, which also earned over $1 million a year in reruns by the mid-1950s, Desilu was able to branch out into several types of production. Desilu also produced TV series and shows for the networks and for syndication, such as December Bride and The Texan. It also contracted to shoot series for other producers, such as The Danny Thomas Show. In October 1956 Desilu sold the rights to I Love Lucy to CBS for $4.3 million. With this money, Desilu then purchased RKO studios for $6.15 million in January 1958. RKO had been the studio where Ball and Arnaz once performed as contract actors. Now, Desi ran the new enterprise, a studio with thirty-five soundstages.

Lucy & Desi on one of their film lots owned by Desilu.

One of the logos used for “The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour” shows broadcast in the 1957-1960s period.

1957-1960

Comedy Hour Shows

After the final episode of the original I Love Lucy series in 1957, a continuation of the series was produced by Desilu Studios as a series of specials. Desi Arnaz had been pushing CBS to allow them to film bi-monthly, one-hour Lucille Ball-Desi Arnaz shows within an anthology series format. He was finally given the green light to do so for Westinghouse’s Desilu Playhouse. I Love Lucy then went into hiatus for two years.

Under the title, The Lucy–Desi Comedy Hour, 13 one-hour specials were produced and aired during the 1957-1960 period. These were hour-long productions as opposed to the earlier 30-minute I Love Lucy format. The first five, shown during the 1957-58 television season, were aired as The Ford Lucille Ball-Desi Arnaz Show. The next eight were shown under the rubric, The Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse Presents The Lucille Ball-Desi Arnaz Show. These episodes, broadcast by CBS, featured the same major cast members, along with a number of celebrity guest actors. CBS also reran the The Lucy–Desi Comedy Hour during some subsequent summers and it was later put into syndication.

When The Lucille Ball-Desi Arnaz Show ended it’s run in 1960, other new CBS shows rose in its place, such as Gunsmoke, The Andy Griffith Show and others. But CBS, since 1959, had also been running I Love Lucy in reruns in primetime and some daytime slots, with good results. Seeing the unending appeal of the series, the network was open to Lucy coming back for a new series, even though she had vowed initially not to do so. In their off-stage life, meanwhile, Lucy and Desi went through a divorce in the summer of 1960.

Screen shot of early logo used for “The Lucy Show,” using stick-figure style from “I Love Lucy” era. Click for DVD series.

The Lucy Show

In 1962, Lucille Ball began a new version of the her TV sitcom without Desi Arnaz. In The Lucy Show, she played the role of widow Lucy Carmichael with two children living in suburban Danfield, Connecticut. Lucy and her children shared their home with divorced friend Vivian Bagley played by Vivian Vance, the Ethel Mertz character from the original I Love Lucy program. Vivian’s character also had a son.

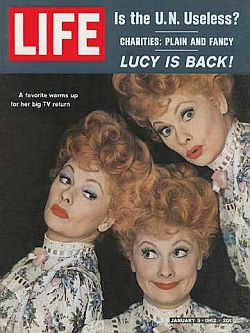

The Lucy Show was formulated in late 1961, when Desilu, then under the direction of Desi Arnaz, was having some difficulty as a few of its shows had been cancelled. Desi offered Lucy an opportunity to do a new weekly sitcom. Some at CBS, however, were doubtful that Lucy could carry such a show without Arnaz, nor follow the success of I Love Lucy. So the show was formulated with the idea of running for a single season. Nevertheless, advance word of the show hit the media in early 1962, as Life magazine ran a cover story with the tagline, “Lucy is Back.”

The Lucy Show initially offered more comic adventures of Lucy and Vivian, now presented in a new package. In this series, Lucy worked part time as a secretary in a bank. The show premiered on Monday night, October 1, 1962, at 8:30 p.m.During the show’s first season, comedian Dick Martin – later of Rowan & Martin/Laugh-In fame – was cast in ten episodes as Lucy’s next-door neighbor, Harry Connors. At the end of its first season, The Lucy Show received rave reviews from the critics and ranked No. 5 in the Nielsen ratings. In 1963, at the beginning of the show’s second season, Desi Arnaz resigned as head of Desilu Productions and as the executive producer of The Lucy Show. Lucille Ball then took over as President of Desilu while continuing to star in The Lucy Show. She was the first woman to ever head up a Hollywood production company.

The Lucy Show ran during a period of major change in television, as color television was then coming on the scene. However, CBS was reluctant push color transmission of its shows, though it had the ability to film in color. During the 1963-64 season, Lucy had the episodes of her show filmed in color even though CBS continued to broadcast the shows in black and white until September 1965. Lucy realized that when the series ended its prime-time run, color episodes would command more money when sold to syndication. CBS reserved color transmission for feature films, then stating it was too expensive and too difficult to use the color equipment for short periods of time. The parent company of CBS rival, NBC, was RCA, then a leader in producing the new line of color TV sets, and CBS was likely reluctant to promote a medium that would profit RCA and NBC. Fewer than 5 percent of the population owned a color TV set in 1963. By the fall of the following year, CBS began broadcasting sporting events and cartoons in color, but not The Lucy Show. Finally, in the fall of 1965, CBS began broadcasting all programming, including The Lucy Show, in color.

An early “Lucy Show” episode finds Lucy & Vivian getting stuck to the walls during a rec room project after underestimating the strength of wall-panel glue.

Comedic episodes, of course, were the stock and trade of the series, with Lucy as the focus in one caper or another, as in one 1963 episode “Lucy and Viv Put In A Shower,” in which the pair try to install a bathroom shower stall but become trapped inside, unable to shut the water off (Ball actually nearly drowned while performing this skit, as in the flooded stall she couldn’t maneuver properly to get to the surface, saved by Vance, who pulled her to the surface). Among other skits in The Lucy Show series were: “Lucy Gets Locked in the Vault,” i.e., a bank vault; Lucy drenching actor Danny Kaye with soup in a restaurant while trying to meet him; Lucy being disguised as the stunt man, ‘Iron Man’ Carmichael” for film work in Hollywood; and the episode, “Lucy Flies to London,” highlighting Lucy’s lack of experience in air travel. Other episodes featured one or more Hollywood stars making guest appearances as they did business at Lucy’s bank. An assortment of straight and humorous characters came into The Lucy Show episodes, such as the “Countess Framboise” (played by Ann Southern), who had been widowed by a husband “who left her his noble title and all of his noble debts.”

Lucille Ball won consecutive Emmy Awards as Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series for the final two seasons of The Lucy Show, 1966–67 and 1967–68. Lucy’s second husband, Gary Morton, became executive producer of the show during the 1967-68 season. Desilu Productions, meanwhile, was sold to Gulf & Western Industries in July 1967, and over the course of the 1967-68 season, Desilu-owned properties were merged with Paramount Pictures, another G & W subsidiary.

“Lucy Show” episode in which Vivian and Lucy are involved with baseball, and in this scene, Lucy appears to be trying to catch fly balls with her trousers.

Among other notable episodes and/or fan favorites from The Lucy Show, are: “Lucy Plays Florence Nightingale”, “Lucy Misplaces Two Thousand Dollars,” “Lucy Conducts the Symphony,” “Lucy the Bean Queen,” “Lucy the Babysitter,” “Mooney and the Monkey,” “Main Street USA,” “Lucy Meets the Law,” and “Lucy Gets Caught in the Draft.” There were also a number of shows with other stars – “Lucy and Phil Silvers,” “Lucy and George Burns,” Lucy and Paul Winchell,” and “Lucy and John Wayne.” It was also on The Lucy Show that Carol Burnett appeared with Lucy, in selected episodes, including “Lucy Gets a Roommate” and “Lucy and Carol in Palm Springs.” When The Lucy Show ended in prime time, CBS began broadcasting it in daytime reruns from September 1968 to September 1972.

During the 1960s, Lucy also did a number of specials, including one filmed in London in 1966 and shot in a mod style, titled “Lucy in London.” It even included a “trippy, hippy tune” according to one source, that was written and produced by rock `n roll maestro Phil Spector. The show featured the Lucy Carmichael character cavorting around London in mod attire with the British rock group The Dave Clark Five, then popular in both the U.K and America.

1968-1974

Here’s Lucy

TV screen shot of one of the logos used for “Here’s Lucy.” Click for DVD box set of the complete ‘Here’s Lucy’ series (1968-74), 144 episodes.

In the Here’s Lucy series, Lucy has moved to Los Angeles, and was now Lucy Carter with two children, played by her real-life teenage kids, Lucie and Desi, Jr. Lucy was now employed at ‘Carter’s Unique Employment Agency’ by her brother-in-law Harry, played by Gale Gordon. Vivian Vance, Ball’s longtime co-star, also made numerous guest appearances as Vivian Jones through the series.

"Here's Lucy" also featured Lucy's real-life teenage children, daughter Lucie in the middle and Desi, Jr., right. |

1971 CBS ad for “Here’s Lucy” episode when Lucy and TV detective “Mannix” are tied up together and try to escape. |

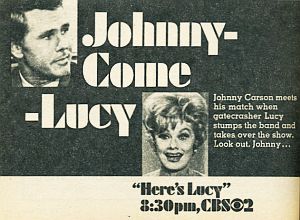

“Here’s Lucy” ad: “Johnny Carson meets his match when gatecrasher Lucy stumps the band and takes over the show...” |

Here’s Lucy also sought to present a “generation gap” struggle between a working mother and her two increasingly independent teenagers. Episodes of the series also touched upon current events – civil rights, rock music, the sexual revolution and other issues. In the run up to the airing of the new series in the fall of 1968, some editions of TV Guide ran full-page ads for the show’s debut featuring Lucy with her two kids.

Among Here’s Lucy episodes featuring classic “Lucy moments” are those including: Lucy as down-trodden “Dirty Gertie;” Lucy outfitted as a giant pickle; Lucy sky-diving through the roof of a lodge; Lucy as construction worker with a jackhammer; Lucy as a saxophone player in an all-Nun band; and Lucy and detective star Mannix tied up to chairs trying to make their bound-together escape.

Other episodes featured Lucy organizing a strike against her boss, Harrison Carter, and another in which the frenetic Lucy Carter meets famous actress, Lucille Ball — and many more. In a 1969 spy episode, Lucy becomes involved in a Keystone Kops-styled chase scene through L.A. International Airport — an episode given special billing in a TV Guide “close-up” feature. In a 1971 Here’s Lucy episode, Carol Burnett and Lucy salute the stars of old Hollywood as they recruit jobless entertainers to stage a variety show. Among the spoofs: Carol and Lucy perform as Betty Grable and Alice Faye, Lucy does a Marlene Dietrich song, and Lucie Arnaz joins in a dance salute to Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson.

A number of Hollywood stars and other famous celebrities appeared on Here’s Lucy, typically serving as a focal point of one comic skit or another, among them: Patty Andrews of The Andrews Sisters, Ann-Margret, Frankie Avalon, Jack Benny, Milton Berle, Lloyd Bridges, George Burns, Ruth Buzzi, Carol Burnett, Johnny Carson, Petula Clark, Sammy Davis, Jr., Tennessee Ernie Ford, David Frost, Eva Gabor, Jackie Gleason, Helen Hayes, Don Knotts, Liberace, Dean Martin, Eve McVeagh, Joe Namath, Wayne Newton, Donny Osmond, Vincent Price, Tony Randall, Buddy Rich, Joan Rivers, Ginger Rogers, Dinah Shore, O.J. Simpson, Danny Thomas, Lawrence Welk, Flip Wilson, and Shelley Winters.

“Here’s Lucy” 1970: Actor Richard Burton looks on as Lucy and Liz Taylor struggle to remove Liz’s diamond ring from Lucy’s finger in the opening episode that year. Episode 1, Season 3.

In that show, Ball’s trademark slapstick talents were on view in one famous scene in which Lucy tries on Elizabeth Taylor’s famous large diamond ring, which of course, gets stuck on Lucy’s finger. Television sitcoms by this time were also willing to take on more controversial material, and as one reviewer later commenting on the Burton-Taylor appearance noted, “the show’s writers had a field day, stuffing it with references to the famous couple’s fights and drinking binges.” Richard Burton, however, was reportedly not fond of Ball’s directorial manner, and would later say so with a harsh critique in his memoir.

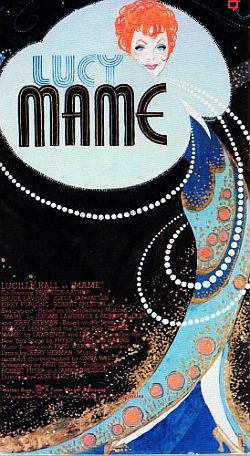

In 1972, Lucille Ball broke her leg in a skiing accident, and was in a full leg cast. The show’s writers then gave Lucy Carter a broken leg as well. But now, Lucy’s physical comedy skits were limited, and some believe that marked the beginning of the end of Lucy’s career and her best years. But at the time, Lucy’s lesser role in the Here’s Lucy series, gave other members of the cast a chance to shine, including young Lucie Arnaz and featured players Mary Jane Croft and Vanda Barra. One 1972 show, for example, had Donny Osmond falling for young Lucie after she comes to one of his concerts. A show spin-off with young Lucie, in fact, was briefly considered, including a pilot, but never went forward.During the various Lucy TV series dating to the original show, Lucy and Desi earlier, and Lucy later by herself, would sometimes engage in outside film or stage ventures, such as the 1953 film with Desi, The Long, Long Trailer and Yours, Mine, and Ours of 1968 with Henry Fonda and Van Johnson. In 1973-74, while still involved with Here’s Lucy, Ball became involved as the lead star in the musical film Mame, a production that did not fare well at the box office. In the reviews, some of the critics were quite hard on Lucy’s role in the film. Time magazine said, “. . . Miss Ball has been molded over the years into some sort of national monument, and she performs like one too. Her grace, her timing, her vigor have all vanished.” She was also compared to former stars who had played the role, with one critic saying she “simply hasn’t the drive and steel of a Rosalind Russell, an Angela Lansbury or a Ginger Rogers…” But other critics were more generous. Judith Crist writing in New York Magazine, was displeased with the film but supportive of the star: “Lucille Ball is–and no ‘still’ about it–a first-rate entertainer, supplementing her superb comedic sense with a penetrating warmth and inner humor. She is without peer in making a hung-over stagger from bed to bathroom an exercise in regal poise, in using her slightly crooked smile to vitiate the soppiness of an overly sentimental sequence, in applying her Goldwyn Girl chorine know-how to a dash of song and dance.” Yet it appeared by that time Lucy’s better days were behind her.

|

“CBS Love Affair” Season/Show Rank/Share I Love Lucy The Lucy Show Here’s Lucy _______________________ Source: Generated from Appen- |

In the spring of 1973, the Here’s Lucy TV show had fallen to No. 15 in the ratings – the first time a Lucille Ball series had fallen out of the top ten. It appeared the series might end with the fifth season, as Lucy was again satisfied there were enough episodes for syndication. However, CBS president Fred Silverman convinced Lucy to change her mind and she returned for a sixth season. The show ceased production at the end of that season. Here’s Lucy had run for 144 episodes, 1968-1974. And like the other Lucy series, Here’s Lucy would also have an afterlife in syndication, appearing first in daytime reruns May to November 1977, and in later years, for example, on the PAX Network in 1998, on Australia’s Go! channel beginning in May 2010, and also on Cozi TV in August 2014.

Era’s End

In 1974, with the formal end of the Here’s Lucy series in regular broadcasting, some 23 years of Lucille Ball appearing regularly on television also ended. Reportedly, it was Lucille Ball’s decision to end the series, even though it still had what many regarded as a “respectable” 29th in the Nielsen ratings. But television and the TV sitcom were then changing. CBS had already begun more contemporary shows such as The Mary Tyler Moore Show, All in the Family, The Bob Newhart Show, and M*A*S*H. The last of the “old guard” shows like Gunsmoke, were in their final years. At the beginning of 1974, Lucille Ball had been the last performer from TV’s classic age who still had a weekly series. Still, CBS, for more than two decades, had enjoyed a Lucy show of one kind or another that ranked consistently at or near the top of the TV ratings for all those years, generating millions in advertising revenue.

Thereafter there were intermittent Lucy specials. In 1977, for example, Vance and Ball were reunited one last time in the CBS special, “Lucy Calls the President,” which also co-starred Gale Gordon. In 1986, Lucy tried a comeback with another sitcom, Life with Lucy. Initially the show debuted on ABC with good ratings, landing in Nielsen’s Top 25 (#23) for its opening episode, September 20th, 1986. But after eight episodes, Life With Lucy was canceled by ABC owing to low ratings. Still, the original I Love Lucy was airing in reruns all over the world – as were some of the subsequent Lucy shows as well.

Rerun Heaven

Keeps on Giving

Back in 1951, when Lucy and Desi first negotiated a contract with CBS and Philip Morris, a point of contention emerged over where to produce the series. CBS and the sponsor wanted the program broadcast live from New York, as was then the prevailing practice. Most of the network’s production facilities were located there as well. TV then was also predominately a live medium. For personal reasons Ball and Arnaz wanted to stay in Hollywood, where they had made their home for several years. A compromise was made to “film” the shows for I Love Lucy. But the increased costs of shooting became an issue for CBS.In the early television industry, the concept of the viable and profitable rerun hadn’t yet formed, as many in the industry wondered who would ever want to watch a program a second time? Those costs were then offset by Arnaz and Ball agreeing to take a cut in their weekly salary. In return, CBS agreed that Arnaz and Ball would own the shows after they were filmed and broadcast, which would prove to be a huge windfall not fully appreciated by either side at the time.

At one point during I Love Lucy’s second season (1952-53), when Lucy was pregnant, she was not able to fulfill the show’s 39-episode production schedule. As a substitute, Desi and producer Jess Oppenheimer decided to rebroadcast some popular episodes from the series’s first season to help give Lucy the rest she needed. The rebroadcasts unexpectedly proved to be ratings winners, and that’s when Lucy and Desi, and the rest of the industry, started to see the possibility of rerun gold. In the early television industry, the concept of the viable and profitable rerun hadn’t yet formed, as many in the industry wondered who would ever want to watch a program a second time? Syndication had not yet started. But the CBS concession, giving Lucy and Desi the I Love Lucy rights, would alone make Desilu Productions at that time one of the most powerful independent companies in television. Desilu made many millions of dollars on I Love Lucy rebroadcasts and became a textbook example of how a show can become profitable in second-run syndication. By the late 1990s, the price of broadcasting a single episode of I Love Lucy was a handsome $100,000.

May 1994 newspaper ad running in The Toledo Blade (OH), for cable’s Nick-at-Nite reruns of “I Love Lucy.”

When I Love Lucy joined Nick at Nite in 1994, a week-long marathon called “Nick at Nite Loves Lucy” aired, showcasing every one of Lucille Ball’s sitcoms that aired between 1951 and 1986 (I Love Lucy, The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour, The Lucy Show, Here’s Lucy and Life With Lucy).

As of July 2007 in the Los Angeles area, I Love Lucy remained the longest-running program to air continuously almost 50 years after production ended. The series in later years was aired in the Los Angeles market on KTTV on weekends and KCOP on weekdays. In January 2009, I Love Lucy moved to the Hallmark Channel. In December 2010, a Me-TV digital subchannel also began carrying I Love Lucy.

Speaking at a Goldman Sachs media and communications conference in New York city in September 2012, CBS Chief Executive Leslie Moonves said that I Love Lucy was then still delivering about $20 million a year in revenue.Speaking at a Goldman Sachs media and commu-nications conference in September 2012, CBS chief executive Leslie Moonves said that I Love Lucy was still delivering about $20 million a year in revenue. In December 2013, CBS re-aired a colorized, digitally remastered version of the I Love Lucy Christmas special, along with the episode, “Lucy’s Italian Movie,” which includes the classic grape-stomping scene. That special attracted 8.7 million viewers.

Periodically over the years, selected I Love Lucy episodes, special broadcasts, and Lucy Christmas shows have demonstrated that I Love Lucy programming can still draw sizeable audiences. A December 1989 airing of the 1956 I Love Lucy Christmas episode garnered CBS an 18.5 rating, placing it No. 6 on the Nielsen list for the week of December 18th that year. CBS and others have also repackaged, reworked and reissued I Love Lucy programs and other Lucy-related material. In April 1990 CBS released a previously unseen, 40-year-old, 34-minute pilot for the I Love Lucy series as a TV special hosted by Lucie Arnaz, with interviews and clips from other popular Lucy episodes. In May 2006, Paramount released I Love Lucy: The Complete Sixth Season, and Warner Home Video released The Lucy & Desi Collection, a set of three movies the couple had made.

Lucy offering a famous pose during a November 1953 episode of “I Love Lucy” involving knife throwing.

The Lucy Legacy

Apart from its continuing popularity in reruns all around the world, I Love Lucy and its related shows – and Lucille Ball – have collected special recognition from a variety of sources for years. In 1964 there was a “Lucy Day” at the New York World’s Fair. In 1971, Lucy was designated “Comedienne of the Century” at a benefit show, “To Lucy With Love,” held at the L.A. Music Center. In 1990, I Love Lucy became the first show to be inducted into the Television Hall of Fame. And over the last 50 years or more, thousands of devoted Lucy fans and fan clubs have continued to tout the show and its founder.

In July 1996 at the 45th anniversary of I Love Lucy, some 500 fans descended on the Burbank Airport Hilton in Southern California for the country’s first-ever national, Lucille Ball convention. “Loving Lucy ’96,” was the convention’s title, a three-day gathering that included panel discussions by I Love Lucy cast members and writers, an auction of Lucy memorabilia, and a 45th birthday I Love Lucy banquet.

An “I Love Lucy” U.S. stamp issued back in the days when the going rate was 33 cents.

I Love Lucy and/or its various episodes have also done well on various “best of” and “greatest hits” lists. In 1997, the episodes “Lucy Does a TV Commercial” and “Lucy’s Italian Movie” were ranked respectively, No. 2 and No. 18 on a TV Guide list of the “100 Greatest Episodes of All Time.” In 2002, TV Guide ranked I Love Lucy No. 2 on its list of the “50 Greatest TV Shows,” behind Seinfeld and ahead of The Honeymooners. In May 2003, CBS aired Lucy, a TV film on the life of Lucille Ball. In 2007, Time magazine placed I Love Lucy on its list of the 100 best television shows.

Lucy in a relaxed pose, as she begins to sample the health tonic “Vitameatavegamin” she is supposed to be selling in a famous 1956 “I Love Lucy” episode.

At the 60th anniversary of I Love Lucy show in the fall of 2011, there were numerous celebrations and special gatherings honoring the show, including those at the Hollywood Museum in Los Angeles, the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, and the Paley Center for Media in New York city. Google also did a special Lucy salute, partnering with the Lucy Desi Center for Comedy in Jamestown, NY. In 2013, TV Guide ranked I Love Lucy as the third greatest show of all time. Lucille Ball, in fact, appeared on more TV Guide covers than any other TV star. (See also at this website, “Lucy & TV Guide”). At least a dozen books have also been written about Lucille Ball, Desi Arnaz, and the I Love Lucy show. These range from in-depth biographies to various academic treatments, some of which are cited below in “Sources.”

|

Lucille Ball  Lucille Ball with cigarette observing a rehearsal or reading of some kind, likely in a Desilu studio or sound stage. Wanda Clark, Lucy’s personal secretary for more than 25 years from 1963 to 1989, put it this way: “She didn’t go around doing ‘I Love Lucy’ shtick, but she had a great sense of humor and she loved to have a good laugh.” Others found her to be a great practical joker.  In 1953, during shooting of “The Long, Long Trailer” film, Lucy has a look through the lens. Actor Tony Randall, a guest on Lucy’s show in the 1970s, told People magazine: “A lot of people found her very, very tough to work with. She bossed everybody around and didn’t spare anybody’s feelings. But I didn’t mind that because she knew what she was doing. If someone just says, ‘Do this!,’ it’s awful if they’re wrong. If they’re right, it just saves a lot of time. And she was always right.” Gale Gordon, who co-starred with Lucy in three of her television shows, noted: “No one worked harder than Lucy. There weren’t any 10 men who could keep up with her.” But Lucy appears to have been fair to those who worked with her and praiseworthy of work well done, often acknowledging and giving credit to her writers as important and key players in her radio and TV success. And Lucy’s loyalty, especially to her employees, was well known, as she hated to let anyone go from their jobs at Desilu.  Lucy’s stage observations, continued – woman at work. But Wanda Clark says “the real” Lucille Ball was “warm and wonderful and generous – to all of us that worked with her…” And she was loyal, added Clark, “that’s why we were all so loyal to her.” Gary Morton, her second husband, said of his wife: “The first thing I noticed about Lucy was her warmth. The second was her carriage.” She was “like a thoroughbred,” Morton would say; when she walked into a room, you knew she was there. |

Lucy in a farewell Charlie Chaplin pose.

Yet the “Lucy effect” – in business terms – went well beyond Desilu, also enriching CBS, TV Guide, and the TV nostalgia industry for nearly 70 years. Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz – their energy, their craft, and the opportunities they seized along the way – left a pretty amazing mark on the entertainment industry and the larger culture; one that appears to be in motion still.

For additional stories on “Film & Hollywood” or “Celebrity & Icons,” please visit those pages. See also the “Noteworthy Ladies” topics page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 26 January 2015

Last Update: 13 March 2019

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “CBS Loved Lucy: 1950s-1970s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, January 26, 2015.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Lucille Ball in her early years in Hollywood. |

Lucy and Harpo Marx clowning during the 1950s. Harpo appeared in May 1955 episode of “I Love Lucy.” |

Two “I Love Lucy” episodes from Oct 1955 have Lucy & Vivian stealing the concrete slab of John Wayne’s Hollywood footprints at Grauman’s Theater in L.A. |

1956: Lucy in French bistro scene from "Paris at Last" episode when she is served escargot by French waiter played by Maurice Marsac. Hilarity ensues when Lucy clamps the snail tongs to her nose, not knowing their purpose. “This food has snails in it,” she exclaims to the insulted waiter, who is then horrified when she says she might be able to eat them with ketchup, close to a French sacrilege. |

1967: Carol Burnett in “Lucy Show” episode when she and Lucy attend school to become airline stewardesses. |

“Here’s Lucy” episodes (1968-1974), also featured Lucy’s real-life teenage children, Lucie, left, and Desi, Jr. |

Part of a TV magazine ad for the 1972 season premiere of “Here’s Lucy” with star Lloyd Bridges as Lucy’s doctor after she broke her leg (in real life & in the show). |

April 27, 1989: Front page of the New York Post at the death of Lucille Ball, age 77– “We Loved Lucy.” |

“Lucille Ball: Television Producer, Executive, Director, Actress,” The Paley Center For Media.

“I Love Lucy: An American Legend,” Exhibition, U.S. Library of Congress.

Christopher Anderson, “I Love Lucy,” Museum of Broadcast Communications / Encyclopedia of Television, Archive of American Television.

“I Love Lucy,” in, Tim Brooks and Earle March, The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows, 1946-Present, Eighth Edition, New York: Ballantine Books, 2003, pp. 566-568.

Steve Hanson and Sandra Garcia-Myers, “I Love Lucy,” St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, 2002, Gale Group.

“List of I Love Lucy Episodes,” Wikipedia .org.

“Beauty Into Buffoon: Lucille Ball’s Slapstick Makes Her a Top TV Star,” Life, February 18, 1952, pp. 93-97.

“Sassafrassa, the Queen,” Time, May 26, 1952, cover, pp. 62-68.

Leonore Silvian, “Laughing Lucille,” Look, June 3, 1952, pp. 7-8.

Jack Gould, “Nearing Birth of (?) Arnaz Is Engendering Interest of Fans of ‘I Love Lucy’,” New York Times, January 16, 1953, p. 29.

United Press, “Lucille Ball Adheres to Television Script; Comedienne Gives Birth to 8 1/2-Pound Boy,” New York Times, January 19, 1953.

Jack Gould, “Why Millions Love Lucy,” New York Times, March 1, 1953.

“Desilu Formula for Top TV: Brains, Beauty, Now a Baby,” Newsweek, January 19, 1953, Cover story, pp. 56-59.

Albert Morehead, “‘Lucy’ Ball,” Cosmo- politan, January 1953, Cover, pp. 15-19.

Jess Oppenheimer,”Lucy’s Two Babies,” Look, April 21, 1953, pp. 20-24.

“There’s No Accounting for TV Tastes,” TV Guide, September 4, 1953, p. 20.

“Lucille Ball Was Red in 1936; I Love Lucy Star Denies Commie Now,” The Herald Express (Los Angeles), 1953.

Testimony of Lucille Desiree Ball Arnaz, Before the U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Un-American Activities, “Investigation of Communist Activities in the Los Angeles Area — Part 7,” Hollywood, California, Friday, September 4, 1953, Room 512, 7046 Hollywood Boulevard, Hollywood, California., Hearing Commencing at 2 P. M., William A. Wheeler, Investigator.

Scott Harrison, “Lucille Ball Explains 1936 Communist Link,” Los Angeles Times, September 15, 2011.

I Love Lucy Comics, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1954, New York: Dell Publications Co., 1954.

“The Desi-Lucy Love Story,” Look, Cover Story (with Keith Thibodeaux; Robert Vose, photographer), December 25, 1956.

Lloyd Shearer, “Desilu: The Story of an Empire,” Parade, October 13, 1957.

Pete Martin, “I Call on Lucy and Desi,” Saturday Evening Post, May 31, 1958.

“Arnaz and Ball Take Over as Tycoons $30 Million Desilu Gamble,” Life, October 6, 1958. Photographed for Life by Leonard McCombe

Dan Jenkins, “A Visit With Lucille Ball,” TV Guide, July 18, 1960.

“The Lucy Show”(1962-1968), Wikipedia .org.

“The Lucy Show” (and “Here’s Lucy’), 1962-1974, in Tim Brooks and Earle March, The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows, 1946-Present, Eighth Edition, New York: Ballantine Books, 2003, p. 710.

“Here’s Lucy”(1968-1974), Wikipedia.org.

“The Lucy Show Episode Guide,” LocateTV .com.

“The Lucy Show Episode Guide,” AngelFire .com.

“Here’s Lucy – Episode Guide,” TV.com.

“The Ten Best Here’s Lucy Episodes of Season Five,”(1972-73), JacksonUpperco .com, June 24, 2014.

Desi Arnaz, A Book, Morrow, 1976, 322pp.

Douglas T Miller and Marion Nowak, The Fifties: The Way We Really Were, Garden City, NY: Doubleday,1977.

David Halberstam, The Powers That Be, New York: Alfred A. Knopf: 1979.

Bart Andrews and Thomas J. Watson, Loving Lucy: An Illustrated Tribute to Lucille Ball, Macmillan, January 1982, 226pp.

Bart Andrews, The ‘I Love Lucy’ Book, New York: Doubleday, 1985.

Joe Morella and Edward Z. Epstein, Forever Lucy: The Life of Lucille Ball, Lyle Stuart, October 1986, 268pp.

Charles Higham, Lucy: The Real Life of Lucille Ball, St. Martin’s Press, 1986, 261pp.

Peter B. Flint, “Lucille Ball, Spirited Doyenne of TV Comedies, Dies at 77,” New York Times, April 27, 1989.

Susan Schindehette, Suzanne Adelson, Doris Bacon, Leah Feldon, Lee Wohlfert, “Remembering Lucy: Friends and Family Share Memories of Lucy and Her Life Behind the Laughter,” People, Vol. 32, No. 7, August 14, 1989.

William Boddy, Fifties Television: The Industry and Its Critics. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

George Lipsitz, Time Passages: Collective Memory and American Popular Culture, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990.

Alexander Doty, “The Cabinet of Lucy Ricardo: Lucille Ball’s Star Image,” Cinema Journal, Urbana, Illinois, 1990, 29:3-22.

Thomas Schatz, “Desilu, I Love Lucy, and the Rise of Network TV,” in Robert J. Thompson and Gary Burns (eds.), Making Television: Authorship and the Production Process, New York: Praeger, 1990.

Warren G. Harris, Lucy and Desi: The Legendary Love Story of Television’s Most Famous Couple, Simon & Schuster, October 1991, 351pp.

William H. Chafe, The Paradox of Change: American Women in the Twentieth Century, New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Camille Baron-Smith, Enterprising Women: Television Fandom and the Creation of Popular Myth, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992.

Lynn Spigel, Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Coyne Steven Sanders and Tom Gilbert, Desilu: The Story of Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, New York: William Morrow & Co., 1993.

David Halberstam, The Fifties, New York: Villard Books, 1993, 197-98.

Kathleen Brady, Lucille: The Life of Lucille Ball, New York: Hyperion, 1994.

Lucille Ball with Betty Hannah Hoffman, Love, Lucy, New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1996, 286pp.

Andrew Blankstein, “A Ball in Her Honor: Burbank Convention Celebrates Lucy’s Television Legacy,” Los Angeles Times, July 20, 1996.

Tim Frew, Lucy – A Life In Pictures, Metro Books, 1996, 96pp.

Steven Stark, Glued to The Set: The 60 Television Shows and Events That Made Us Who We Are Today, New York: The Free Press, May 1997.

Steven Stark, “The Lucy Chronicles – Before Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem, Lucille Ball Played an Unapologetically Ambitious Woman Who Challenged Her Husband’s Authority and Wasn’t Afraid to Be Funny. Was Lucy TV’s First Feminist? Ask June Cleaver,” Los Angeles Times, May 4, 1997.

Gregg Oppenheimer (for his father, Jess), Laughs, Luck …and Lucy: How I Came to Create the Most Popular Sitcom of All Time, New York: Syracuse University, December 1996, 312pp.

Lori Landay, Madcaps, Screwballs, and Con Women: The Female Trickster in American Culture, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998.

Lori Landay, “Millions ‘Love Lucy:’ Com- modification and The Lucy Phenomenon,” NWSA Journal (National Women’s Studies Association), Vol. 11, No. 2, Summer 1999, pp. 25-47.

Stuart Galbraith IV, (DVD Review), “Here’s Lucy – Best Loved Episodes from the Hit TV Series,” (Shout Factory, August 17, 2004), DVDTalk.com, July 27, 2004.

Madelyn Pugh Davis with Bob Carroll, Jr., Laughing with Lucy: My Life With American’s Leading Lady of Comedy, Clerisy Press / Emmis Books, September 2005, 288pp.

Susan King, “For the Love of Lucy and Desi,” Los Angeles Times, May 2, 2006.

“Lucille Ball: Finding Lucy,” American Masters/PBS.org, September 21st, 2006.

Filmmaker Interview – Pamela Mason Wagner and Thomas Wagner, “Lucille Ball: Finding Lucy,” American Masters/PBS.org, September 21, 2006.

Michael Karol, The Lucy Book of Lists, iUniverse.com, December 2009.

Belinda Man, Research Paper, “Desilu: The Family, The Success, The Productions, and Its T.V. Impact,” Evergreen.edu, 2009-2010.

Elisabeth Edwards, I Love Lucy: Celebrating 50 Years of Love and Laughter, Running Press, 2010, 301pp.

“Magazines With Lucy on the Cover,” Glen Charlow’s Lucille Ball Collection, LucilleBall.net, as of June, 15, 2010.

Lori Landay, I Love Lucy, Wayne State University Press, 2010, 119pp.

“‘I Love Lucy: An American Legend’ Opens Aug. 4,” Library of Congress, July 20, 2011.

Stephen Battaglio , “I Love Lucy Goes Live! – Today’s News: Our Take,” TVGuide.com, September 14, 2011.

S. Rothaus, McClatchy-Tribune Newspapers, “Museums, Events Celebrate 60th Anniversary of ‘I Love Lucy’, Lucille Ball’s Centennial,” Tampa Bay Times, Saturday, September 24, 2011

Bill Newcott, From: AARP Radio, “Do You Still Love Lucy? Celebrate the Funny Lady’s 100th Birthday,” AARP.org, August 2, 2011.

Joe Flint, “’I Love Lucy’ Still a Cash Cow for CBS,” Los Angeles Times, September 20, 2012.

Margot Peppers, “Talk About Loving Lucy! Polka Dot Dress Worn by Lucille Ball on Fifties Show Fetches a Whopping $168,000 at Auction,” Daily Mail (London), August 7, 2013.

Marcela, “Loving Lucy Day 4: The Story of the Aftermath,” Best-of-The-Past, Sunday, October 14, 2012.

“Favorite Wife, My Favorite Redhead – In Fact, That’s The Only Thing Red About Her,” Desi & Luci Blog, December 23, 2012.

Marcela, “Audrey Hepburn and Why I Wouldn’t Want to Be an Icon,” Best-of-The-Past, Saturday, January 12, 2013.

Billy Ingram with Dan Wingate, “The Lost Lucy Themes,” TVParty.com.

“Was Lucy (Lucille Ball) Funny in Real Life?,” A Blog About Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, June 19, 2013.

Christopher Rudolph, ‘I Love Lucy’ Premiered 62 Years Ago: Let’s Celebrate!,” The Huffington Post, October 15, 2013 (selection of Lucy faces & skits )

___________________________