Sketch of the DMC - "the DeLorean" sports car -- later built by the DeLorean Motor Co. in 1981-82.

This would be the same guy who would later found the DeLorean Motor Company, inventing and producing the DMC-12 sports car, also known as “the DeLorean.” And DeLorean was also the guy whose name would appear on a “tell-all” book about GM — On A Clean Day You Can See General Motors. But at the moment, Mr. DeLorean was caught up in the “leaving-GM” controversy.

John Z. DeLorean, in fact, had been a rising star on the GM fast track; a good bet to run the place and become CEO. But DeLorean had done the unthinkable: he had quit his high-level post at General Motors (some say he was fired), doing so with controversy and in his own style.

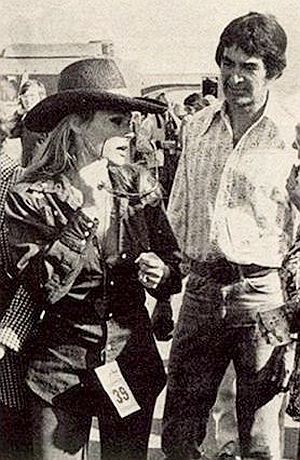

Early 1970s photo of John DeLorean that ran in Fortune magazine. By then he had gone through some personal changes, lost weight, became fit & lived a full social life, clashing with the expected GM executive model. Photo, Anthony Edgeworth.

The Fortune piece was a post-mortem on the whys and wherefores of DeLorean’s departure. But it also became hot fodder for water-cooler gossip at GM since it showed the six-foot-four DeLorean shirtless in one photo, a buff 48 year-old in good trim, and also working out with weights in another.

‘Picture Star’

“He looked like a million-dollar picture star,” remarked Hollywood producer Pierre Cossette, who had met DeLorean about that time, “like he had been put together by the property department of M-G-M.,”

No, John DeLorean wasn’t your typical, every day GM executive, especially in those last few years near the top of the company. In fact, the guy had quite a reputation on his climb up the corporate ladder – known for dating Hollywood starlets and models, wearing tapered Italian suits, and roaring around town in high-performance Maseratis and Lamborghinis. Yet John DeLorean was also a dedicated automotive professional. He had become a highly competent GM executive in a leadership role, boosting GM’s fortunes in two of its divisions and operating at the industry’s highest levels.

GM Wunderkind

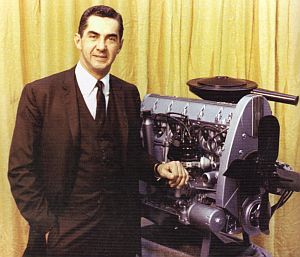

John Z. DeLorean as he appeared in August 1965, a rising star at General Motors featured here in a “Car Life” magazine spread on his success with the Pontiac GTO.

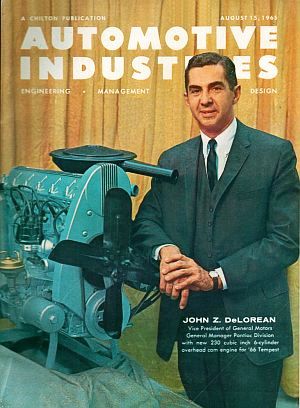

In 1971, he was featured in Business Week. In 1972 he appeared on the cover of Automotive Industries magazine with his overhead cam engine. By 1973, he was GM’s vice president and group executive for North American cars and trucks — a huge swath of the General Motors empire, encompassing Chevrolet, Buick, Oldsmobile, Pontiac, Cadillac, GMC, and Canadian car and truck operations. Total sales of this group at the time were $25 billion, placing it among the top echelon of only a handful of other businesses worldwide.

John DeLorean, then 48, was one of four other group-level vice presidents, and he held more GM turf than his peer Roger Smith, who would later run the company. In fact, many believed John DeLorean, too, was on the “candidate track” to run GM, and those who worked with him thought he was a sure bet to do just that.

Yet, when he made it to the company’s prestigious “14th floor”headquarters – the inner sanctum sanctorum of global auto power in those years – John DeLorean, by the early 1970s, was not exactly fitting in. Rather, DeLorean was running counter to GM’s management culture.

John DeLorean doing the company’s bidding on his way to the 14th floor, before his cultural makeover.

In the mid-1950s when DeLorean was recruited to GM’s Pontiac division by Bunkie Knudsen, he was viewed as a hard worker and straight-arrow; just the kind of creative young man the company would want to groom for its top leadership positions. “He wasn’t flamboyant or anything; just a nice young man,” Knudsen would say of DeLorean when he hired him. And before rising to the lofty heights of GM’s command center, DeLorean had toiled for many years in the engineering bowels of the auto industry, notching some impressive accomplishments. He would later claim to have a number of patents, and would be credited for a number of automotive innovations, including the concealed windshield wiper, the overhead cam engine, and the windshield-embedded radio antenna.

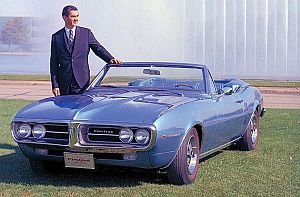

John DeLorean began his rise in GM's Pontiac Division. |

John DeLorean with Pontiac Firebird model, later 1960s. |

Streets of Detroit

John DeLorean’s roots were in the hard scrabble streets of Detroit, where he played stickball as a kid. His father had worked in a Ford foundry. Young John proved a bright kid who applied himself in school, landing at Cass Technical High School for Detroit’s honor students, considered a feeder school for the Big Three.

At “Cass Tech,” as it known locally, DeLorean excelled, then winning a scholarship – not in engineering, but in music – to attend the Lawrence Institute of Technology. DeLorean would later study industrial engineering there. At night for pocket money he played the saxophone at “black and tan” clubs, as the mixed-race jazz clubs were then called.

In 1943, during WWII, his education was interrupted when drafted into the U.S. Army. After his three-year hitch, he returned to Lawrence to complete his degree in mechanical engineering.

He then had a series of odd jobs thereafter, including a stint selling insurance before enrolling in a post-graduate engineering program at the Chrysler Institute, earning an M.A. there in industrial engineering in 1952. He was also working at Chrysler by then as well.

DeLorean would later add an MBA from the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business, attending at night, and he also studied law briefly.

In the mid-1950s, DeLorean moved to the Packard car company where he became director of research and development. At Packard, among other things, DeLorean improved the efficiency of their automatic transmissions by adding something called “a lockup clutch” that directly linked the engine to the wheels. Eliminating slippage in an automatic transmission provides much better fuel economy and lower temperatures.

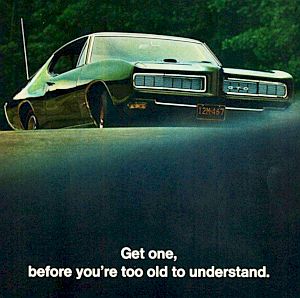

1968 magazine ad for Pontiac GTO: “Get One, Before You’re Too Old to Understand.” DeLorean’s GTOs of the 1960s pitched power & speed to American youth.

At Pontiac, in September 1956, DeLorean’s first title was director of advanced engineering. He was 31 years old.

After a few years at Pontiac, DeLorean rose to assistant chief engineer, and then chief engineer of the Pontiac division.

But in the early 1960s, working with Estes and Knudsen, DeLorean helped turned the fortunes of the Pontiac division around. What they came up with was a new “wide track” design; producing cars with longer axles and powerful engines. Initially, new high-powered Catalina and Bonneville models were quite successful. But the best was yet to come.

The GTO

1960s: John DeLorean receiving a Motor Trend award for his work on the Pontiac GTO.

From 1964 through 1974, each of Detroit’s then “big four” automakers all offered muscle cars – among these were AMC’s Rebel SSTs, Plymouth Road Runners, Chevrolet Chevelles, Dodge Chargers and more. [ However, with the 1973 OPEC oil embargo and the emergence of the Clean Air Act and 1975 auto emissions standards, the muscle car era cooled off considerably by the mid-‘70s.]

|

“GTO Marketing” In 1969, Brock Yates, writing in Sports Illustrated, would describe some of the GTO marketing that ensued under Pontiac ad executive, Jim Wangers: “… Realizing, with DeLorean and Estes, that rival manufacturers were plunging into the performance market with bigger, hotter cars than the GTO, [Wagners] launched a text book sales promotion campaign that included the pop hit, ‘Little GTO’, recorded by Ronnie and the Daytonas [the writer of the song, reportedly, had come to Pontiac for advice and accuracy of lyrics]. While by-passed in the Grammy awards, ‘Little GTO’ got to No. 3 on the charts, sold 1.2 million copies and got played an estimated seven million times on the nation’s rock radio stations – ground zero for the GTO market. At the same time Wangers flooded the nation with GTO shoes, emblems, T-shirts and more records until every kid from Portland, Maine to West Covina, California was stuffing his piggy bank in anticipation of the day he could purchase a GTO. In 1965, 65,000 GTOs were sold. The following year sales soared to 83,000.” (Brock Yates, Sports Illustrated, 1969). |

But in the mid-1960s, the GTO was immensely popular with young drivers when it first came out. Nearly 250,000 of the fast and classy “hot rods” were sold in the first five years of production. As a result, Pontiac’s sales tripled.

It was also during DeLorean’s years leading the Pontiac division that he developed a prototype sports car – a 1964 concept model named the Pontiac Banshee. However, this project was halted since it would have been direct competition for the Chevrolet Corvette, GM’s marquee performance sports car. But it was this idea that would later lead to DeLorean’s plan for a future automotive venture, the DMC-12. More to come on this later. Still, it is alleged that DeLorean’s Banshee model was raided by others at GM for features incorporated into the 1968 Corvette.

By 1965, the high-flying success of the GTO helped send Bunkie Knudnsen up the ladder to GM corporate, Pete Estes to become general manager at Chevrolet, and DeLorean as top man at Pontiac. He was now making more than $200,000 a year. It was at this juncture in John DeLorean’s rise in the auto establishment that he appeared to begin something of personal metamorphosis.

“After giving Pontiac its new style,” Newsweek would report, “DeLorean gradually transformed himself from a button-down conformist to a vain, middle-age clotheshorse. He lost 60 lobs., began lifting weights and started draping his 6-ft’ 4-in. frame in brightly colored shirts, turtlenecks and nipped-at-the-waist suits…” He also dyed his hair, and according to some sources, had facial work done as well.

DeLorean began to enjoy the freedom and celebrity that came with his position, and spent a good deal of his time traveling to locations around the world to support promotional events. His frequent public appearances helped to solidify his image as a “rebel” businessman with his trendy dress style and casual conversation.

DeLorean also became more of a free spender, and open to new business opportunities. By 1966 he had acquired a 10 percent share of the San Diego Chargers football team, and could be found at times visiting with the team’s head coach, Sid Gilman, or star players like receiver Lance Alworth.

General Motors executive John DeLorean, shown on first of a 2-page spread in ‘For Men Only,’ June 1969. |

Fast cars, flashy females, and sideline access to pro football games were part of this DeLorean story. |

In June 1969, the magazine For Men Only, ran a feature story on DeLorean (above) with the title, “The Women-and-Wheels Life of Johnny DeLorean – General Motors’ 200 M.P.H., Million Dollar Swinger.” As a tag line on the article’s next page put it, “At the wheel of the world’s fastest cars, dating the flashiest females of the Jet Set, or being on the field with your own pro football team are dreams to most men, just another day to ‘Johnny Z’.”

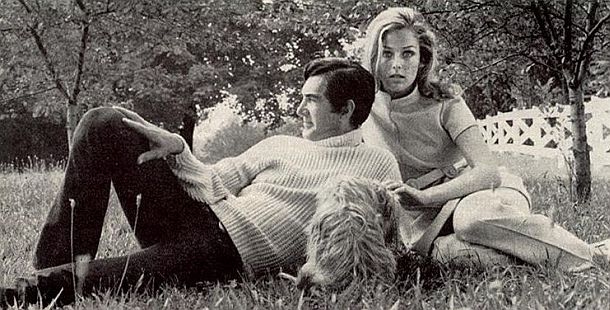

DeLorean, then age 43, had divorced his wife of 15 years. In late May 1969 he married Kelly Harmon, 21, the daughter of football legend Tom Harmon, described by one writer as “the uncrowned Miss America.”

1969: John DeLorean relaxing with his young wife, Kelly Harmon, outside their home. Photo, Sports Illustrated.

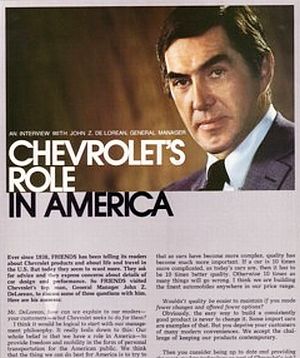

After his success at Pontiac, DeLorean was promoted to the top job at the company’s Chevrolet division, GM’s flagship brand. He was the youngest man ever to head up the huge division. DeLorean was recruited for the job by GM’s CEO at the time, as Chevy was in some difficulty, with declining sales and dealer profits down. Over the next few years, DeLorean executed a turn around at Chevy, which helped solidify his management bona fides (although there were some “misses” in this period, as well, including a rather mixed record on GM’s sub-compact, “import fighter,” the Chevrolet Vega, related to the vehicle’s quality, durability and performance. DeLorean, for his part, would later claim that he was “called upon by the corporation to tout the car far beyond my personal convictions about it.”). Still, under his leadership at the time, Chevrolet in 1971 became the first Big Three division to sell more than 3 million vehicles a year. And dealer profits that year had also soared by 400 percent.

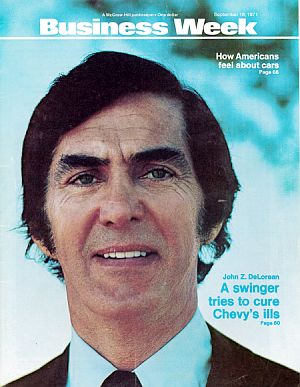

1971 Business Week: “A Swinger Tries to Cure Chevy’s Ills”. |

1973 Newsweek photo of John DeLorean shown with actress Ursula Andress at an outdoor event. |

But during his Chevrolet years, because he was on the road so much, and working long hours back in Detroit, there were problems at home. He was not spending enough time with his wife, Kelly, or the son they were adopting. And Kelly, younger than most other executive wives, wasn’t fitting in well either. She missed California. The pair separated in the fall of 1972 and were later divorced.

By October 1972 DeLorean was promoted again, this time as GM’s VP for its entire car and truck group. And after his separation from Kelly, he resumed a free-ranging life style, as described by Paul Ingrassia, former Detroit bureau chief for the Wall Street Journal, in his book, Engines of Change:

… DeLorean started dating Ursula Andress, Raquel Welsh, and other Hollywood starlets. He appeared in gossip tabloids as often as car magazines. On Thursday nights he would commandeer a General Motors jet from Detroit to Los Angeles, where a GM junior executive would meet him with keys to a company car and hotel room in Beverly Hills or Bel Air, He would party through the weekend and fly back to Detroit Monday nights, showing up in the office on Tuesday morning. On Thursday nights, it was back out to Hollywood again.

His bosses tolerated this flight pattern because DeLorean sill produced results. He eliminated layers of management, reorganized engineering,… slashed inventory, and installed computerized financial controls… On September 19, 1971, Business Week touted him on its cover with the headline: “John Z. DeLorean: A Swinger Tries to Cure Chevy’s Ills.”

In 1972, under DeLorean’s leadership, Chevrolet became the first automotive nameplate on earth to sell more than 3 million vehicles in a single years. It was a major milestone, and in October of that year, DeLorean was promoted yet again: to group vice president in charge of GM’s entire car and truck business….

On his way up the corporate ladder at GM, DeLorean had leapfrogged ahead of several promising engineers, some with more seniority. At Pontiac, DeLorean had already been the youngest GM division head at 40. And with his arrival as head of GM’s North American operations, he began collecting his $650,000-a-year paycheck. In his rise, he had occasionally rubbed colleagues the wrong way, made unflattering public statements about other auto executives, or offended important politicians, calling Michigan’s Republican U.S. Senator, Robert Griffin, for example, a “moron.”

Still, in his last couple of years at GM, he continued his jet-setting lifestyle, seen in celebrity circles with noted businessmen and entertainers. In Hollywood, he became friends with James T. Aubrey, president of Metro-Goldwyn -Mayer studios, and was introduced to entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. and The Tonight Show TV host, Johnny Carson. He also met financier Kirk Kerkorian. By then, DeLorean also held a 1.5 percent interest in the New York Yankees baseball team.

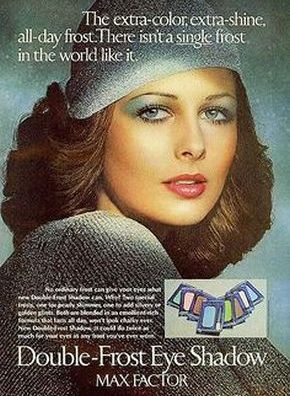

Cristina Ferrare on the July 1974 cover of Cosmopolitan magazine. |

Cristina Ferrare in a 1975 magazine advertisement for Max Factor eye makeup. |

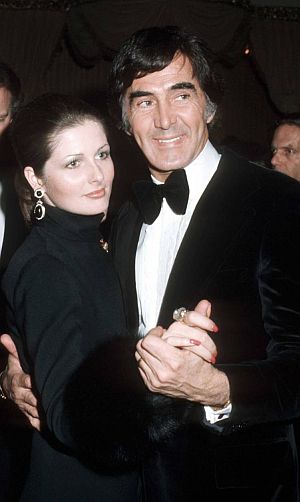

In 1972 DeLorean began dating Cristina Ferrare (above), an American supermodel, who had graced fashion magazine covers. Hired as a model by the makeup company Max Factor when she was 16, Ferrare at 20 signed with the New York modeling agency Eileen Ford. She soon became a cover girl for major fashion magazines and later did TV and film work as well. DeLorean and Ferrare would marry in 1973.

14th Floor Blues

DeLorean’s disaffection with his position at GM began to surface when he moved from heading up the Chevrolet division to becoming a regional vice president. As a head of a car company line, auto executives had public visibility and more hands-on involvement with the business. On the 14th floor, however, although at the center of GM power, life was considerably more boring, filled with lots of meetings, and as some would later speculate, not at all in the style of John Z. DeLorean.

Late 1960s: John DeLorean, far right, at meeting when he was head of the Chevrolet division, where he felt more engaged, could meet with dealers, travel the country, etc., as opposed to life on the 14th floor. Sports Illustrated.

As one friend noted, it was “like putting a straitjacket on Secretariat”(famous thoroughbred race horse). Another observed, “instead of [being] the big cheese at Chevy or Pontiac, he was just another vice president upstairs at the GM staff level.” DeLorean himself would recount one meeting with an executive who told him he should “disappear into the wallpaper up here.” DeLorean, in other words, was being told to tone down his act.

In addition, on the 14th floor, DeLorean’s ideas for GM’s business were being rejected, which was something of a new experience for him. His idea for making restyling changes earlier in the design cycle was nixed, as was the plan to make model changeovers at night and on weekends to keep plant shutdowns at a minimum, which would have saved the company $1 billion by his accounting. His suggestion to meet the 1975 federal air pollution emissions standards (then three years away) with catalytic converters was also rejected – as GM and the Big Three would instead lobby Washington for a one-year extension the Clean Air Act deadline ( the first of many such delays the automakers would win from subsequent administrations and/or Congress). DeLorean, in fact, had caught the attention of some environmentalists and safety advocates who viewed him as someone who might help turn GM in a better direction.

Little Innovation

According to some accounts, DeLorean had misgivings about GM and what he was seeing in the business well before his rise to the 14th floor. Detroit Free Press writer, Paul Hendrickson, noted in a Detroit magazine profile shortly after DeLorean had left GM:“…My concern was that there hadn’t been an important product innova-tion in the industry since the automatic transmis-sion and power steering in 1949…” – John DeLorean

“…By late 1972, there were new rumblings [for DeLorean]. More and more, many of America’s cars were becoming to him just big, vulgar hunks of tin and chrome. At the auto show in [Detroit’s] Cobo hall that fall, DeLorean was repulsed by what he later said was the gaudiness everywhere he looked. He began to question all over again the validity of bending the tin a different direction each year.”

DeLorean’s disenchantment with GM he would later say, actually began “sometime in the late 1960s,” when “a nagging suspicion about the philosophy of General Motors and the automobile business began to overtake me…” At that point he began looking at the company more critically, recalling what he had witnessed over 17 years. “My concern was that there hadn’t been an important product innovation in the industry since the automatic transmission and power steering in 1949. That was almost a quarter century in technological hibernation.”

In place of product innovation, DeLorean charged that the automobile industry “went on a two-decade marketing binge which generally offered up the same old product under the guise of something new and useful.” There really wasn’t much that was new, DeLorean said. “But year in and year out we were urging Americans to sell their cars and buy new ones because the styling had changed. There really was no reason for them to change from one model to the next, except for the new wrinkles in the sheet metal…”“Soon,” he would later write, “I found myself questioning the bigger picture; the morality of the whole GM system…” DeLorean felt that more emphasis on innovations that made a car safer, easier to drive, more trouble free, or more economic to operate would bring true benefit to the consumer. These were new found concerns for DeLorean, who admitted he had been among the stylists who pushed for superficial model changes in the past.

“Soon,” he would later write in a tell-all book, “I found myself questioning the bigger picture; the morality of the whole GM system… The undue emphasis on profits and cost control without a wide concern for the effects of GM’s business on its many publics seemed too often capable of bringing together, in the corporation, men of sound, personal morality and responsibility who as a group reached business decisions which were irresponsible and of questionable morality.” At GM, DeLorean charged, “the concern for the effects of products… was never discussed except in terms of cost or sales potential…”

|

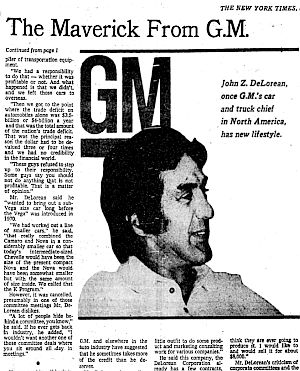

Small Cars In the late 1960s, small cars produced by foreign manufacturers, notably Volkswagen, and later the Japanese, were beginning to penetrate the American market in a noticeable way. But such sales — and the emerging trend — were dismissed for the most part by Detroit’s Big Three automakers, preferring to sell large cars. This was occurring a few years before the 1973-74 Arab oil embargo and resulting U.S. energy crisis, revealing America’s big-car culture to be energy profligate and vulnerable. John DeLorean then headed GM’s Chevrolet division, and he became a voice for trying to move GM away from its large-car bias, a task that proved difficult and bucked up against GM tradition and culture. Here is an excerpt from Jack Doyle’s book, Taken For a Ride, on that period: …Detroit’s heart and soul — and its leadership — just weren’t in the small-car business, a fact often admitted, and for some like Ford engineer Hal Sperlich, deeply lamented. But like Sperlich at Ford, there were a few voices within the industry that tried to push efficiency and smaller car design well before the energy crisis.Cole and DeLorean…were up against the fundamen-tal Alfred Sloan growth dictum of…trading up to bigger cars. At General Motors, Ed Cole and John DeLorean, then head of the GM’s Chevrolet division, had argued for smaller cars in the late 1960s. They pointed to the VW Beetle and the fact that much of the sales growth in the U.S. since 1965 had been in the small car segment. Smaller families, congested roads, higher costs and shifting values were also part of a trend toward a new market segment. But Cole and DeLorean were voices in the wilderness at GM; for they were up against the fundamental Alfred Sloan [formative and legendary GM CEO] growth dictum of GM’s success: trading up to bigger cars. By this rule, every American had a fundamental right (if not an economic obligation) to “trade up” to bigger cars — an idea that has never lost favor in management, even today. Cole and DeLorean — prodding GM to design smaller and lighter compacts and intermediates, while scaling down full-size cars — were bucking tradition. And they ran into GM’s powerful finance committee; then dominated by executives who had served with Sloan, and who were solidly committed to the big-car world view. At John DeLorean’s departure from GM in 1973, he also made remarks on this topic in an October 28, 1973 New York Times story as follows: …The thing that disappointed me was that most of the growth in the auto business in the last 10 years [ 1963-1973] has gone to the foreign cars. [That] business is 1.5 million units, and it’s gone overseas. This is an indictment of our industry. …It was my feeling that we had a moral responsibility to build smaller cars, especially in G.M.’s case as America’s major supplier of transportation equipment.  Clip from October 28th, 1973 New York Times story & interview with John DeLorean by reporter Robert Irvin. We had a responsibility to do that — whether it was profitable or not. And what happened is that we didn’t, and we left those cars to overseas. Then we got to the point where the trade deficit on automobiles alone was $3.5-billion or $4-billion a year and that was the total amount of the nation’s trade deficit. That was the principal reason the dollar had to be devalued three or four times and we had no credibility in the financial world. These guys refused to step up to their responsibility. Some guys say you should not do anything that’s not profitable. That is a matter of opinion. …[I] wanted to bring out a sub-Vega size car long before the Vega [ was introduced in 1970]. We had worked out a line of smaller cars, that really combined the Camaro and Nova in a considerably smaller car so that today’s [i.e., 1973’s] intermediate-sized Chevelle would have been the size of the present compact Nova and the Nova would, have been somewhat smaller but with the same amount of size inside…. [ That program was cancelled ]. However, during DeLorean’s watch as head of the Chevrolet division, the Vega was launched, a small car whose first five years of production saw erratic fuel economy (23 mpg in 1971; 13 mpg in 1973), body rusting within a few months of purchase, a problem-plagued aluminum engine, and various brake, drive-train and rear-axle problems. These shortcomings and others in GM and Ford small cars [i.e., the Pinto] raised troubling questions about the U.S. auto industry’s engineering capabilities — a harbinger of things to come in later years. It also brought forward for the first time in Detroit “the quality issue.” |

Greenbrier Speech

DeLorean’s growing disaffection with GM seemed to bubble up in a speech he was preparing to give at a November 1972 gathering of GM’s top 700 managers in Greenbrier, West Virginia. GM held such meetings every few years or so to have its managers talk candidly about needed internal changes and new perspectives. DeLorean was asked to talk on Product Quality, and his earlier drafts were quite pointed and critical, but later toned down by management. None of the material, in any case, was intended for the public beyond GM. But an earlier draft of DeLorean’s speech was leaked, and made its way into the Detroit News in November 1972.

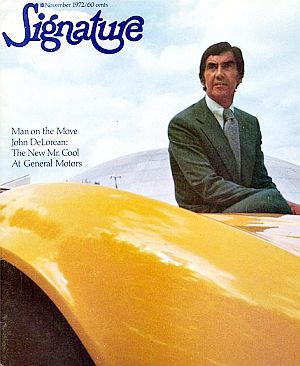

While John DeLorean was having his doubts about GM, the press was still featuring him in cover stories, here with Signature magazine in November 1972 – “Man on the Move John DeLorean: The New Mr. Cool at General Motors.”

DeLorean revealed that GM was then spending as estimated $500 million annually in warranty repairs — a huge sum in the early 1970s. “Poor quality,” DeLorean wrote for his prepared remarks, which were printed in the newspaper, “threatens to destroy us.” DeLorean also noted, “every defect, each recall, only diminishes the credibility of whatever amount of advertising we do.” Poor quality in GM’s cars, he continued, “has already resulted in seriously declining owner-loyalty… and reduced credibility of our promises to do better next time.”

After that speech, GM Vice Chairman Thomas Murphy, who generally had judged DeLorean on his ability and solid business performance, began to lose confidence in him. It was about then as well that DeLorean himself began to realize he was on his way out.

In December 1972, DeLorean wrote a 19-page single-spaced memorandum to Murphy. The memo recounted in great detail what DeLorean believed to be GM’s failings and poor record — on safety and pollution, among other concerns. One small portion of that memo, pertaining to the company’s views on emissions control, is excerpted below:

…In no instance, to my knowledge, has GM ever sold a car that was substantially more pollution free than the law demanded — even when we had the technology. As a matter of fact, because the California laws were tougher, we sold “cleaner” cars there and “dirtier” cars throughout the rest of the nation. This approach of just doing the bare bones minimum to just scrape by the pollution law when GM could do much better by spending a few dollars is not socially responsible. With our virtual monopoly position in the industry we also, in effect,DeLorean argued that GM, with its dominant market position, could lead the industry with socially-re-sponsible technology and push its competitors in that direction as well. control our competitors — who would be economically devastated if they tried to do better socially but at a greater product cost.

We of Chevrolet proposed to the EPG [Engineering Policy Group] that we make our cars cleaner than the law demanded — we were told that the other divisions did not need a $15.00 air pump to meet the law — we were to take it off our cars. Our next proposal was to have all optional engines exceed the law (do the best we knew) since the customer would pay the extra cost anyhow — once again we were not permitted to do so for fear we would lose a few sales…

…Our corporation has lost credibility with the public and the government because each new emissions standard has been greeted by our management’s immediate cries of “impossible,” “prohibitively expensive,” “not economically responsible” — usually before we even knew what it involved. The remarkable thing is that with all of our resources and the amount we tell the government we are spending on emissions research that most of the significant developments in this field have come from someone else — for example, our first answer, the “Clean Air Package,” was developed by a handful of engineers at Chrysler, the manifold reactor which meets the 1975 standard now (and should be in production) was developed by Du Pont with less than 10% of our facilities and manpower. The other 1975 answer, the catalytic converter with EGR, was developed by a small grant given by Ford, several oil companies and several Japanese manufacturers. Not a very good record for a corporation that professes to be vitally interested in emissions. When we tell government about our large expenditures for emissions controls we don’t bother to tell them that very little is being spent on R and D and that most of our money is spent on adapting hardware to our wide variety of engines.

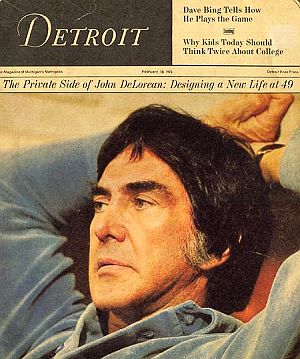

Feb 1974: John DeLorean shown in a reflective pose on the cover of Detroit magazine: “The Private Side of John DeLorean: Designing a New Life at 49.”

In January 1973, after 17 years of making his way to the top of the auto game, John DeLorean took the final plane ride from Detroit to New York to meet with three GM executives to tender his resignation. Some say DeLorean’s departure from GM was not his decision but GM’s, choosing to rid itself of a bothersome critic. Upon leaving, however, DeLorean was awarded a Cadillac dealership in Florida and was owed over $500,000 in bonus pay. And while he planned his next venture, he would also run the National Alliance for Businessmen for one year, an organization that helped find jobs for disadvantaged minorities. GM would pay him a $200,000 salary while he held this post. The resignation letter, which DeLorean signed at GM’s headquarters in New York city after meeting with GM Chairman Richard Gerstenberg and Vice Chairman Thomas Murphy, would become effective on May 31, 1973.

Meanwhile, in his personal life, DeLorean and Cristina Ferrare were married that same month, May 1973. By February 1974, in addition to his home in the Bloomfield Hills of Detroit, he had a string of real estate holdings that included a cattle ranch in Salmon Idaho, an avocado farm in southern California’s Puma Valley, and a D.C. townhouse. Later, a New Jersey estate and a New York city residence would be added.

The Bombshell

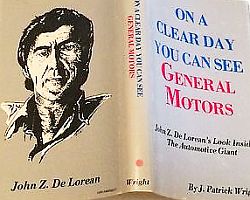

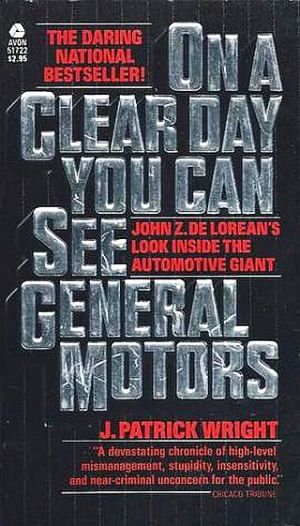

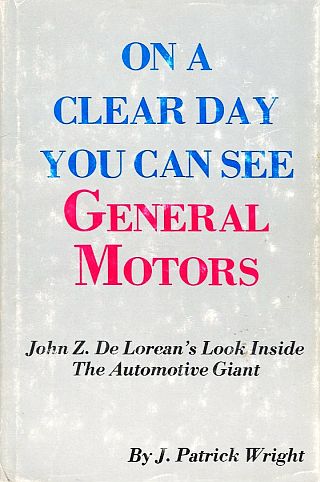

1st edition of, “On A Clear Day You Can See General Motors,” John DeLorean's GM account, as written and published by J. Patrick Wright. Click for book.

Upon leaving GM, DeLorean agreed to collaborate in writing a “tell all” book about his GM experience with J. Patrick Wright, a former Detroit Business Week bureau chief. Wright had covered the auto industry for 13 years.

As the book project got underway in the mid-1970s, and Wright proceeded with the writing, DeLorean began his quest for a new automotive business venture. He planned to build a new sports car, and would found a new auto company to do it; a company he called the DeLorean Motor Company (DMC). The car he planned to build and sell would be called the DMC-12 (more on the venture later below).

However, as DeLorean set about raising money and making connections in the auto industry for suppliers and production, he began to worry about the forthcoming book he and Wright were doing, and possible retaliation from GM on his new-car venture.

For several years, in fact, DeLorean vacillated about publication, frustrating Wright to the point of Wright mortgaging his house to stake the book’s publication. Wright persisted because he believed that what DeLorean had told him about GM, and big business generally, was important for the public to see. Finally, in November 1979, after four years of holding the book off the market, and at least one blown publishing contract with Playboy Press, the book was published — and some controversy began.

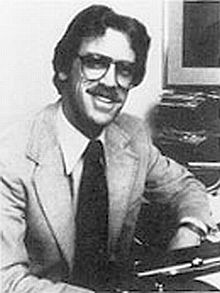

J. Patrick Wright, former Business Week Detroit Bureau Chief.

Wright, who had staked his personal reputation on the book’s publication, also added in the introduction that “much of the factual content, anecdotes, tenor and tone of the book has been confirmed in my own outside reporting.” Wholesalers sold all 20,000 copies of the first edition. Another 20,000 copies were quickly printed.

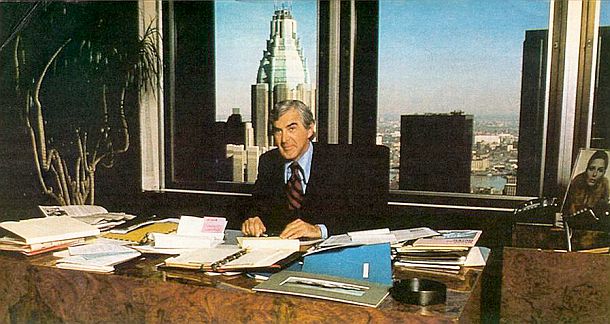

DeLorean, for his part, gave a two-hour interview on the book that November (1979) with several reporters. By then he was well along with plans for his DMC car idea and was then working out of a suite of ultra modern offices atop a Manhattan office building – which had a clear view of GM’s office tower a few blocks away.

Regarding the book, DeLorean acknowledged On A Clear Day to be a true account, and said there were no significant errors of fact and no misrepresentations of his own views about GM. In fact, DeLorean reiterated that he didn’t see a dramatic difference in the GM of that day (1979) compared to the company he had left in 1973. He also offered comment on one current hot Detroit topic: the financial troubles of the Chrysler Corporation. Chrysler at the time, prior to Lee Iaccoca, was near bankruptcy, and complained that government regulation was the cause. “That’s bullshit,” DeLorean said, pointing to stumbles by mistake-prone management, adding however, that he did support government aid to bail out Chrysler.

John DeLorean, in his Manhattan office suite during his DMC planing years in the 1970s, high above New York city.

On A Clear Day, meanwhile, exposed a whole laundry list of GM misdoings — from industrial espionage and contempt for workers, to poor quality in manufacturing and misleading advertising campaigns. The book showed GM’s fledgling attempt to produce the 1968 Vega, a car that was supposed to compete with the VW bug, but instead became an engineering disaster, and was dropped by the end of the 1977 model year.

DeLorean also revealed that the Corvair in 1959 “was unsafe as it was originally designed” and that GM knew it was unsafe and made “an immoral business decision” to produce the car. The Corvair had also been the central subject of Ralph Nader’s 1965 book, Unsafe At Any Speed, to which DeLorean’s charges helped lend further substantiation. On a Clear Day also described the efforts of the company to “squelch information which might prove the [Corvair’s] deficiencies.”In the book, DeLorean also recounts one tale in 1971 of the company’s attempt to destroy 19 boxes of microfilmed complaints from Corvair owners, only to have those boxes come back to GM by way of two Detroit junk dealers who found them, selling them back to GM for $20,000. DeLorean’s management critique of GM, including the increasing centralization of management at the expense of its individual car divisions, would prove to be prophetic as GM and all of Detroit became victimized by their own inertia and myopia during the 1980s.

A number of journalists gave the Wright /DeLorean book glowing reviews. “What we have spread on the record is a stunning account of the venality, narrow-mindedness – yes, even immorality – of one big American business,” wrote Washington Post business reporter Hobart Rowan.

Others, however, were more critical, challenging DeLorean’s motives. Detroit News columnist Robert Irvin found DeLorean’s memory a selective one, and the book “full of gossip” and detailed accounts of office politics and executive pettiness. Still, even Irvin said the book “should be read by students of the auto industry because DeLorean offers some interesting insights and opinions about GM corporate life.”The back jacket of the June 1980 Avon paperback edition leads with a series of press blurbs and offers a summary description:

“Controversial.” – The New York Times

“Damming.” – Saturday Review

“Riveting.” – Chicago Sun Times

In the spring of 1973. John Z DeLorean stunned the business world by handing in his resignation as a Vice President of General Motors. His rise had been meteoric. By his mid-forties he was their most brilliant and flamboyant young executive, earning $650,000 a year and destined to become the next president of the industrial giant. But the higher he rose, the more disillusioned he became. When he saw what really went on along Executive Row – the corruption, the mismanagement, the total irresponsibility at every level – he decided the climb to the top was no longer worth it. He got out.

This is John Z. DeLorean’s story, the unprecedented and unforgettable expose of America’s most powerful supercorporation – the book that blows the lid off the king of carmakers.

On A Clear Day You Can See General Motors sold more than 1.6 million copies, and the book is still used today in schools and colleges for reference and the study of the automobile industry. Meanwhile, Part 2 of the John DeLorean story was already in motion.

The DMC Dream

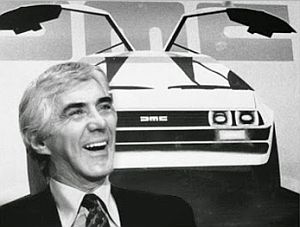

DeLorean in a happier moment, promoting his DMC.

The fact that he could raise the money alone was something of a coup. “No one had ever doubted his talent, for he was one of the most creative young men of his generation,” wrote David Halberstam in his 1986 book on the auto industry, The Reckoning. “Many thought, that his was the most plausible attempt by an American at a start-up [auto] company since that of Henry Kaiser…” Halberstam observed that DeLorean’s flamboyant style and Iacocca-like national recognition, helped him raise the money.

DeLorean needed $175 million to finance his dream. He enlisted more than one hundred investors, including Johnny Carson and Sammy Davis, Jr., who put over $12 million into a partnership for research and development while the British government produced $156 million in grants and loans in return for DeLorean locating the DMC factory in Northern Ireland. (Britain liked the idea of creating 2,000 new jobs in a region suffering a 20 percent unemployment rate.) He also had more than 250 U.S. car dealers sign up as partner/investors, with many of those filing early orders for the car. DeLorean, however, according to some accounts, risked relatively little of his own money — $700,000 by one estimate — but he seemed to be on the road to having his dream come true.

1981: John DeLorean at right showing famous late night talk show host, Johnny Carson – also a DMC investor – some of the internal controls of a DeLorean Motor Car.

And as he pursued his DMC, DeLorean lived in the style of the well-paid business executive that he had become accustomed to. Among his multiple residences in 1982 were, for example: a $7.2 million, 20-room Fifth Avenue duplex; a $3.5 million estate in New Jersey; and a $4 million California ranch. His estimated net worth at the time was $28 million. As DMC’s CEO, his salary was nearly half a million dollars a year. DMC’s New York city offices, meanwhile – in a GM- comparable skyscraper – ran a costly $25,000-a-month.

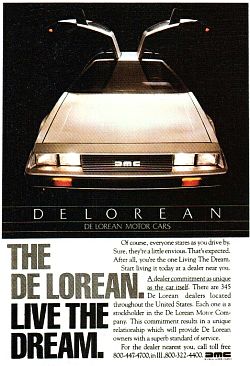

The DMC and DeLorean received quite extensive publicity both in advance of the car’s actual production and as it first became available for sale in 1981-82. The car was featured in a number of prominent auto magazines well before it became available, helping to stoke expectations. And DeLorean himself appeared on magazine covers and in numerous media stories.

Oct 1979: DeLorean w/DMC, billed by Success mag. as a “pioneer in a new era of individual opportunity.” |

John DeLorean & his DMC featured in a laudatory 1982 Cutty Sark profile. |

One 1982 Cutty Sark Scotch whisky advertisement — featuring DeLorean’s face and his DMC — offered a profile that was especially laudatory, opening with the headline: “One Out of Every 100 New Businesses Succeeds. Here’s to Those Who Take the Odds.” And the ad’s text gave DeLorean rave reviews:

John DeLorean was on the way to the presidency of General Motors when he quit to build his own car company. In his 17 years with GM he helped quadruple Pontiac sales, built Chevrolet into a 3-million seller and was awarded 44 automotive patents. While his bosses railed at him for wearing his hair too long.

Now his stainless steel DeLorean Sports Car is here. Designed to last 20 years rust free. And the first year’s production is sold out.

John DeLorean anticipates the needs and wants of car buyers. He does no less for the scotch drinkers he invites to his home. That’s why he selects and serves the impeccably smooth Cutty Sark… The Scotch with a following of leaders…

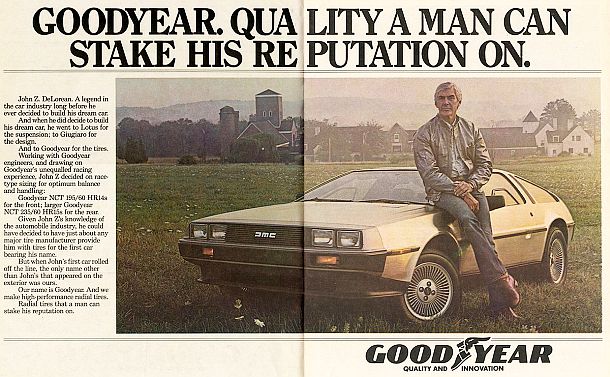

Automobile suppliers were also eager to use DeLorean and his upcoming DMC in their product advertising. Goodyear, for example, ran a double page magazine spread in about the DMC’s use of their tires on the new model, with DeLorean along for the photo shoot. “Goodyear. Quality A Man Can Stake His Reputation On,” read the ad’s headline, with DeLorean getting good press in the ad’s copy (below):

Circa 1981-82. Goodyear’s double-page magazine ad touted the man and the car -- and of course, its own tires on the car.

John Z. DeLorean. A legend in the car industry long before he ever decided to build his dream car. And when he did decide to build his dream car, he went to Lotus for the suspension; to Giugiaro for the design.

And to Goodyear for the tires.

Working with Goodyear engineers, and drawing on Goodyear’s unequalled racing experience, John Z. decided on race-type sizing for optimum balance and handling:

Goodyear NCT 195/60 HR14s for the front: larger Goodyear NCT235/60 HR15s for the rear.

Given John Z’s knowledge of the automobile industry, he could have decided to have just about any major tire manufacturer provide him with tires for the first car bearing his name.

But when John’s first car rolled off the line, the only name other than John’s that appeared on the exterior was ours.

Our name is Goodyear, And we make high-performance radial tires.

Radial tires that a man can stake his reputation on.

March 2, 1981. Automotive News reporting on the first DMCs produced in Ireland.

“Today’s transverse engine front-wheel-drive layouts,” he wrote in an April 1981 New York Times Op-Ed piece, “differ little from the British Layland mini [car] of 25 years ago…” In that same piece, he also suggested that a then-advertised GM efficiency feature was hardly cutting edge:

“I remember my first visit to the GM proving ground in October 1956. I rode in a 1956 Chevrolet with John Dolza, GM’s noted engine engineer. In this particular car, he had rigged the V-8 engine to run on all eight cylinders when maximum power was required and to cruise at highway speeds on only four cylinders to save fuel. That was 24 years ago. [emphasis added]. A Cadillac advertisement recently touted that a V-8 that accelerates on eight cylinders and cruises on four is 1981’s hottest feature…”

After a fair amount of hype and numerous false starts, the production of his $25,000 V-6-powered, stainless-steel, gull-winged DMC-12 finally began in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The snazzy car debuted in February 1981. In Los Angeles there was an unveiling of the car at the Biltmore Hotel on February 8th, 1981 with Johnny Carson, DeLorean, wife Cristina Ferrare and others.

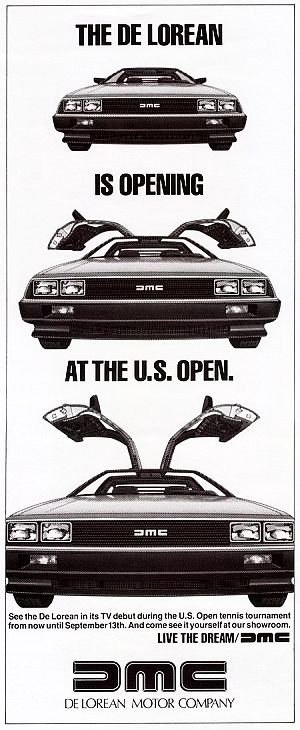

One of the print ads that ran in 1982 for the DMC, using the theme, 'The DeLorean: Live The Dream'.

But the DMC’s introduction and early sales were not without glitches. There were some quality problems with the cars, though these for the most part were quickly addressed with a series of Quality Assurance Centers set up to correct problems before the cars went to the dealers. But entering the market in 1981 there was lower priced competition in the sports car class from Datsun, Mazda, and Porsche. The DMC, at $26,000, cost $8,000 more than a Chevy Corvette. There was also a recession during 1981-82. The hoped-for sales of 12,000 DMCs a year fell short by half.

DeLorean then faced a raft of DMC-related financial difficulties – not least of which was money owed against some very weak cash flow. He had sought a second round of financial help from the British Government without success (which some believe could have helped the company survive and was shortsighted by the Thatcher government). Other sources of financial help were limited, with earlier backers tapped out. And that’s when some believe John DeLorean ventured into desperate territory.

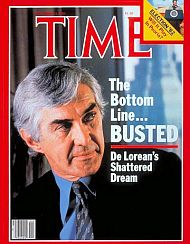

“Busted”

In the fall of 1982, DeLorean’s fortunes changed rather abruptly when he walked into the middle of an FBI drug sting in Los Angeles. There he was videotaped in an airport hotel meeting with 50 pounds of cocaine in a briefcase while saying, “it’s as good as gold,” a reference to the drug’s possible street value. This was DeLorean’s assumed move to help generate the large amounts of capital he needed to keep his car company afloat. But now he was busted; arrested and charged with conspiring to sell drugs. But the arrest was just the beginning of a very public prosecution and trial that would stretch over nearly 2 years.

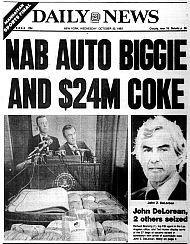

New York Daily News front page on DeLorean drug bust, Oct. 22, 1982. |

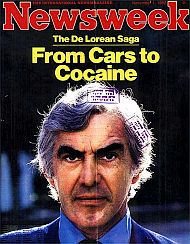

Newsweek’s Nov. 1st, 1982 story on DeLorean: “From Cars to Cocaine.” |

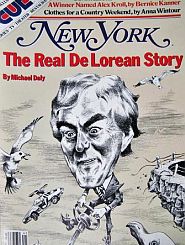

The bust was something of a media event, with Time, Newsweek and many newspapers giving the story top billing and front-page treatment. DeLorean’s trial following his arrest fueled the tabloids for months. There were stories in People magazine featuring DeLorean and wife Cristina. One unflattering profile of DeLorean appeared in a New York magazine cover story by Michael Daly titled, “The Real DeLorean Story.” Rather than the well-intentioned maverick businessman with tendencies toward ethical car production and righting callous corporate decision making, DeLorean, in this piece, was characterized as a ruthless operator and something of a con man, leaving a trail of unhappy business partners, self-interested investments, and litigation by various wronged parties. According to this piece, a range of creditors, former partners, and government agencies all had him in court for a variety of charged offenses, from breach of contract an unpaid attorney fees to racketeering and income tax evasion.

Nov. 1982. New York magazine cast DeLorean in unflattering story. |

April 1984. People magazine at trial time asks: “Will He Get Off?” |

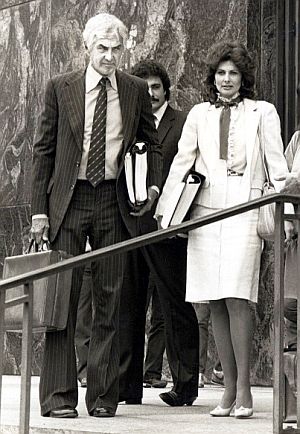

Back at the main event, however – DeLorean’s drug trial and the government’s alleged conspiracy case against him – he had pled not guilty and his attorney mounted a defense that charged the government agents (who had first posed a legitimate investors) with entrapment and luring DeLorean into the drug deal. It was a strategy that won the day. DeLorean was acquitted of all charges in 1984 – “not so much because the jury believed him,” wrote David Halberstam in his book, The Reckoning, citing those who had followed the case, “but rather because ordinary Americans did not like the idea of their government setting up its citizens…”

Detroit Free Press headlines of August 17th, 1984 on “not guilty” verdict in DeLorean’s drug case. Second headline: “Tapes Were Dramatic, But Didn’t Sway Jurors.”

“…But the most telling argument for the defense was the woman who sat at [DeLorean’s] side most days, descended like a fairy princess from the ether of her high-fashion world to give the jury a lesson in wifely devotion. Surely Cristina Ferrare DeLorean — loyal, chic, and smart – would not be the moll of a drug peddler. Nobody ever said that in so many words, but it was a question the jury had to ponder every time the faithful wife appeared in the courtroom. The government said that DeLorean acted out of greed; his lawyers said he acted out of fear, to protect his family from drug dealers. The jury, weighing the model of matrimonial devotion against the testimony of often bumbling government operatives, decided that evil was not in the mind of John DeLorean.”

By this time, the British Government had closed down DeLorean’s DMC plant in Ireland in 1983, which still had several hundred cars in stock and others on the production line. He and his company, meanwhile, would become ensnared in business-related litigation for years thereafter. In the end, fewer than 10,000 DMC cars were produced. But many of those cars have had an amazing second life, with more than 6,000 in fact still in use today, testament to their “no rust” billing. More on that in a moment.

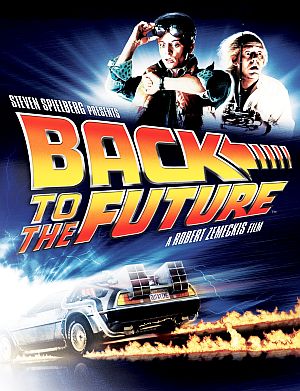

Poster for “Back to The Future,” now a three-film, $1 billion franchise with a universe of related products. Click for DVD.

Back To The Future

One happy development for DeLorean’s legal troubles and his legacy, however, came in 1985, with the Hollywood film, Back to the Future, starring Michael J. Fox as Marty McFly and Christopher Lloyd as the slightly unhinged but lovable Doc Brown. The film used the DMC-12 as one of its main characters: the time-travelling machine aiding Marty and Doc in their adventures.

In fact, there were three Back to the Future films (1985, 1989, and 1990) and the then-defunct DeLorean DMC-12 car received a huge popularity boost throughout the world. The three films have grossed nearly $1 billion to date, and DeLorean through the 1980s and 1990s collected millions in licensing fees from all three, plus a piece of the action from a related animated television series, toys, games, and other Back to the Future paraphernalia.

The income generated by the DMC’s starring role in the Back to the Future franchise helped to keep DeLorean afloat as creditors, partners, and government agencies pursued him for various damages, taxes, and fees. The DMC, meanwhile, lives on.

In 1995, Liverpool-born mechanic and business entrepreneur, Stephen Wynne, started a separate company using the “DeLorean Motor Company” name. He would also acquire the remaining parts inventory (in fact, quite substantial and enough to build a couple hundred new DMCs) and the “DMC” logo trademark. Now based in the Houston, Texas area, and known informally as “ DMC Texas”, this company has five franchised dealers in Florida, Illinois, California, Washington and the Netherlands helping to service existing DMCs, of which some 6,000 are believed to be still in operation. And as of January 2016, this company was also building new DMCs in limited numbers, some priced around $100,000. The DMC has also become something of a car-collectors favorite, with a number of clubs and/or fan websites devoted to the car and its history.

Tougher Times

John DeLorean, meanwhile, had a tougher life following his failed car effort and his battles with the government. He divorced again in 1985, married for a fourth time, and led a much quieter life through the 1990s. Still, he was seen occasionally in media photos, attending social events. However, by 1999, after fighting some 40 court cases related to his failed car company, he filed for bankruptcy. Among assets and personal property sold were his 1978 Yankees World Series ring (he held a minority stake in the team) and his 434-acre estate in Bedminster, New Jersey. The estate was purchased by Donald Trump for part of a golf course.

John DeLorean did not, however, let go of his new car ideas. In May 1999, a wire story noted he had another new car in the works – this one built with structural composite that could go zero-to-60 mph in 3.2 seconds and would cost $18,000. “Cars are in my blood,” he said at that time, “they’re really the only thing I’ve ever worked at.” But he never returned to the industry. In March 2005, John DeLorean died after a stroke. He was 80 years old. Still, to this day, DeLorean remains an intriguing figure for journalists and auto historians. At least half a dozen books have been written about him, along with several TV and film documentaries. In 2017, a new Hollywood film on DeLorean was reported to be in the works, and there is also a DeLorean Museum located in Humble, Texas.

“…Heart of a Hippie”?

Charles Madigan, writing a profile of DeLorean for the Chicago Tribune in October 1982 at the news of his drug arrest, offered the following sketch:

John Z. DeLorean was a man tailor-made for success, a bold and brilliant engineer with a plan to ride to glory in a stainless steel sports car.

He was a Henry Ford with some rock ‘n roll mixed in. He was fireworks instead of stuffiness. He built cars and talked about the ethics of industrial America. He became a media favorite.

It was almost too good to be true, a man with the brains of a capitalist and the heart of a hippie, the kind of character who would walk away from one of the most powerful positions in American industry to “do his own thing.”…

Dan Neil, writing a 2005 retrospective on the DeLorean/ GM era in the Los Angles Times, suggested that GM and DeLorean needed each other, and implied that if each side had come half way in working with each other, perhaps the historic outcome would have been different:

What if DeLorean and GM had reconciled?

It certainly seems now they needed each other. GM needed the bold strokes of an unconventional thinker such as DeLorean. He needed the coat-and-tie discipline of the 14th floor. If the collapse of the DeLorean Motor Co. proves anything, it’s that the bean-counters have their place.

With the DMC-12, DeLorean had in mind an “ethical sports car”: a car that would be fun to drive, practical, safe, offer good fuel efficiency and value… And — as the stainless steel body suggests — he wanted it to last a long time. He argued that the endless churn of automotive obsolescence was a waste of money and resources.

In this respect, DeLorean was one of the rare Detroit auto executives who — along with futurists such as Buckminster Fuller and Norman Bel Geddes — saw the automobile as part of a progressive vision of the world, where transportation was framed by social and environmental impera-tives….

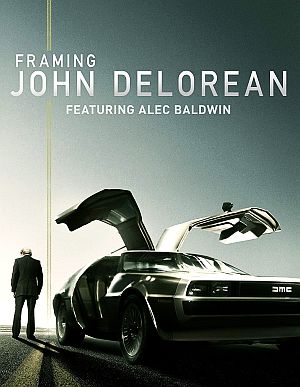

“Framing John DeLorean,” a 2019 American documentary film, stars Alec Baldwin as DeLorean. Click for film.

As for the DeLorean saga, on one level, it illustrates the difficulty in trying to make modest change in an automobile culture that – with all its moving parts, resource requirements, urban congestion, pollution, wastes, and parallel consumption – is now well into its second century of roiling the planet and most major cities.

For additional stories on General Motors at this website see, for example: “Dinah Shore & Chevrolet”, “Smog Conspiracy: DOJ vs. Detroit Automakers,” and “G.M. & Ralph Nader.” See also the “Business & Society” and “Environmental History” topics pages for stories in those categories.

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing, and continued publication of this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 15 June 2017

Last Update: 3 August 2021

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “The DeLorean Saga: Car Guy, 1960s-1980s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, June 15, 2017.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Aug 15, 1965. John DeLorean, then General Manager of GM’s Pontiac Division, posing with new 6-cylinder overhead cam engine, among America's first mass-produced overhead-cam engines, ahead of its time on several fronts. |

October 1972. Delivering the Chevy vision in the company magazine, “Friends” as top man at Chevrolet. |

March 1975: John DeLorean and Cristina Ferrare at The Balloon Ball, Hotel Pierre, New York, NY. |

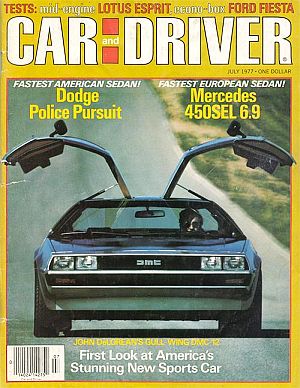

July 1977: Early media attention for DeLorean’s DMC-12 prototype helped stoke expectations for the car. |

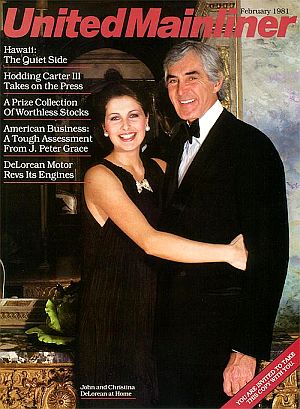

Feb 1981. John & Cristina DeLorean featured on cover of United Airlines’ “United Mainliner” in-flight magazine with tagged story, “DeLorean Motors Revs Its Engines.” |

Print ad used to pitch DMCs mid-1981 during U.S. Open tennis tournament; also mentions DMC’s debut TV ad. |

May 1984. DeLorean and Cristina during drug trial in L.A. Cristina filed for divorce in 1985. Photo, Ron Galella. |

“John DeLorean,” Wikipedia.org.

“DeLorean Motor Company,” Wikipedia.org.

“DeLorean DMC-12,” Wikipedia.org.

Tamir’s DeLorean Site (good DeLorean history source).

Howard Pennington, “Mr. GTO,” Car Craft, January 1967.

Robert Flowers, “The Women-and-Wheels Life of Johnny DeLorean,” For Men Only, June 1969.

Brock Yates, “New Kind Of Wheel At GM,” Sports Illustrated, December 15, 1969.

Al Rothenberg, “Powerhouse Behind the Vega,” Look, August 25, 1970, pp. 54-57.

“A Car Is Born,” Look, April 2, 1979.

James Mateja, “An Auto Pioneer’s Bold Venture,”Success Unlimited, October 1979, pp. 15-17.

AP, “DeLorean Hits Poor Car Quality,” Chicago Tribune, Business Section, November 18, 1972.

Karl Ludvigsen, “Man On The Move: John DeLorean – He Made The Push Come to Chevy,” Signature, November 1972.

“`Poor Quality Threatens Us,’ DeLorean Tells Colleagues,” Automotive News, November 27, 1972, p. 25.

“The Non-Organization Man,” Newsweek, April 30, 1973.

Rush Loving, Jr., “John DeLorean: The Automotive Industry Has Lost its Masculinity,” Fortune, September 1973.

Robert Irvin, “The General Motors Maverick,” New York Times, October 28, 1973, p. F-1.

Paul Hendrickson, “The Private Side of John DeLorean: Designing a New Life at 49,” Detroit Magazine (Detroit Free Press), February 10, 1974.

Julie Greenwalt, “The DeLoreans: Swinger Tycoon Gets Domesticated Model,” People, July 29, 1974.

Stephen B. Shepard and J. Patrick Wright, “The Auto Industry,” The Atlantic, December 1974, pp. 18-27.

Ralph Nader, “GM Defector’s Choice: New Sports Car or a Book,” Nader.org (archive), October 15, 1977.

William Flanagan, “The Dream Car Of John DeLorean,” Esquire, June 19, 1979.

Charles Madigan (Chicago Tribune), “Tragedy of John DeLorean,” The Day (New London, CT), October 24, 1972, p. 1.

Fred M. H. Gregory, “DeLorean — Back Again, With a New Car,” New York Times, Sunday, September 18, 1977, p. 173.

Charles Ewing, “Betting on the Luck of the Irish” DMC 12 A Gamble,” Washington Star (Washington D.C.), March 17, 1979.

“The $200 Million Car” New York Times, October 28, 1979.

Peter J. Schuyten, “A G.M. Struggle On Corvair Detailed,” New York Times, November 9, 1979, p. D-1.

Edward Lapham, “DeLorean Book Debuts Minus OK,” Automotive News, November 12, 1979, p. 3.

William H. Jones, “Views In GM Book Confirmed,” Washington Post, November 15, 1979, p. B-1.

Hobart Rowen, “A Stunning Account Of How GM Works,” Washington Post, November 18, 1979, p. G-1.

Robert W. Irwin, “DeLorean Doesn’t Tell All,” Automotive News, November 26, 1979, p. 3.

Martha Smilgis, “G.M. Renegade John DeLorean Toots His Own Horn with a New Life, New Book and a New Car,” People, January 7, 1980.

Clarence Ditlow, “Making It At GM,” Environmental Action, February 1980, pp. 28-30.

William G. Flannagan, “Personal Affairs: Belfast Buggies,” Forbes, January 5, 1981.

Associated Press (Belfast, Northern Ireland), “DeLorean’s Dream Starting To Come True; Delays, Irish Conflict Haven’t Stopped New Car,” February 21, 1981.

John Z. DeLorean, “Engineers Should Run The Auto Business,” New York Times, April 26, 1981.

Associated Press (Los Angeles, CA), “DeLorean, Co Defendants Plead Innocent,” November 9, 1982.

“DeLorean: The High Road to Ruin,” Life, December 1982, pp. 178-179.

“John DeLorean and The Icarus Factor,” Inc. (magazine), April 1983, pp. 35-42.

“DeLorean’s Decline,” Newsweek, February 22, 1982.

Judith Cummings, “DeLorean, Automobile Executive, Arrested in Drug Smuggling Case,” New York Times, October 20, 1982.

Dow Jones & Co., “Dream Of Building Car Company Is Over For DeLorean,” Edited Wall Street Journal Stories, October 22, 1982.

“A Life In the Fast Lane; Genius, Jet-Setter, Rebel; The Boy From Detroit Became A Driven Man,” Time, November 1, 1982, p. 34

Roger Rosenblatt, Essay, “The Man Who Wrecked The Car,” Time, November 1, 1982, p. 90.

“Finished: DeLorean Incorporated; The Rise and Demise of A Stainless Steel Miracle,” Time, November 1, 1982, p. 37.

“From Cars to Cocaine,” Newsweek, November 1, 1982.

Pete Axthelm, “Why It Went Wrong,” Newsweek, November 1, 1982, p. 38.

Jeff Jarvis, “Downfall Of An Auto Prince,” People, November 8, 1982.

Bernice Kanner, “When You Wish Upon A Car: DeLorean’s Difficulties,” New York Magazine, February 22, 1982, pp. 19-20.

Thomas Bevier, “DeLorean Was Reportedly Investigated While at GM,” Detroit Free Press, Sunday, January 9, 1983.

Aaron Latham, “Anatomy of a Sting: John DeLorean Tells His Story,” Rolling Stone, March 17, 1983.

Don Sharp,, “Grand Delusions: The Cosmic Career of John DeLorean,” Book Review, Dream Maker: The Rise and Fall of John Z. DeLorean, by Hillel Levin,” Commentary, January 1, 1984.

Michael Ryan, “De Lorean’s Days Of Reckoning: Wife Cristina Stands By Him, But the Drug Trial is Only The Beginning…,” People, April 16, 1984, pp. 96-106.

“DeLorean vs. Almost Everybody. Was He Entrapped, Or Just Caught in the Act of Being Himself?,” Time, April 30, 1984.

Linda Deutsch, Associated Press, “A Designer Style, A Fall From Grace, Detroit Free Press, August 17, 1984, p.15-A.

“DeLorean: Not Guilty. The Ex-Auto Executive Beats The Government’s Sting,” Newsweek, August 27, 1984.

“The DeLoreans: Why Did Cristina Split?”, People, October 8, 1984, pp.47-48.

Michael Ryan, “The DeLoreans: Most Intriguing Split,” People, December 24, 1984, pp. 134-135.

“John DeLorean Finally Gets Cross-Examined,” Playboy, October 1985.

Ivan Fallon and James Srodes, Dream Maker: The Rise and Fall of John Z. DeLorean, Putnam Publishing Group, November 1985, 455pp.

Hillel Levin, Grand Delusions:The Cosmic Career of John De Lorean,

William Haddad, Hard Driving, Random House, 1985.

John DeLorean with Ted Schwartz, DeLorean, Zondervan, 1985.

David Halberstam, The Reckoning, New York: William Morrow & Co., September 1986, 752pp.

Ralph Nader & William Taylor, The Big Boys: Power & Position In American Business, New York: Pantheon Books, 1986.

Associated Press, Detroit, “$53 Million Case Against DeLorean Stands,” Chicago Tribune, Sunday, April 2, 1989, Section 7, p. 10.

“The Man,” DeloreanMuseum.org.

George Mahlberg, “DeLorean: Stainless Style” (re: specs, collectors & investors), Bloomberg, March 1998, pp. 107-110.

Jason Manning, “10. The Rise and Fall of John DeLorean,” 2000.

Jack Doyle, Taken For A Ride: Detroit’s Big Three and The Politics of Pollution, New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, June 2000.

Dan Jedlicka, “Ambitious DeLorean Planning A Comeback,” Chicago Sun-Times, Business, Tuesday, October 3, 2000, p. 48.

Lucy Kaylin, “Wings of Desire. After a Drug Arrest and Bankruptcy, 75 Year-Old Maverick John DeLorean Wants to Build A New Car For You,” GQ (Gentleman’s Quarterly), September 2000, pp. 320-324.

“John DeLorean: This Automotive Visionary Took A Detour,” People, August 2001, p. 122.

Al Rothenberg, “Back To The Future: GM is Reviving The GTO and Architect John DeLorean Has Plenty To Say About It and The Carmaker,” Chicago Tribune, Cars Section, June 6, 2002, p. D-1.

Dan Neil, “Detroit’s “Kid Notorious’ Was Creative Force Behind The GTO; John Z. DeLorean Put the Car on the Map by Being in Touch with All Things Young,” Los Angeles Times, November 19, 2003.

“DeLorean: Winging Its Way Home, Call it Nostalgia, But Motor Buffs in The UK Are Now Buying A Car With A Bad Reputation and Fantastic Look, ” UK Metro, March 18, 2004, p. 15.

Dan Neil, “DeLorean: A Vision Clouded by Vanity. The Automaker Lived Fast and His Burnished Dream Died Young, The Icon of an Age of Excess,” Los Angeles Times, March 23, 2005.

Edward Lapham, “John DeLorean: Maverick Exec Was Talented, Devious — and Never Dull

Rising Star Ruffled Feathers at GM, Made Headlines with Failed Sports Car Venture and Scandals,” Automotive News, September 14, 2008.

Edward Lapham, “DeLorean Didn’t Fit the GM Mold; Talented, Quirky Exec Played by His Own Rules, Ruffled Corporate Feathers Along the Way,” Automotive News, October 31, 2011.

Richard Retyi, “The Stainless Steel Life of Playboy Carmaker John Z. DeLorean; Inventor of the GTO. Father of the DeLorean. Lover. Huckster. Genius,” Road & Track, March 17, 2014.

Wallace Wyss, “Unsung Heroes – The Story of John DeLorean,” CarBuilderIndex.com, June 16, 2015.

Wallace Wyss, “The Legend of Long Tall John,” CarBuilderIndex.com, October 22, 2015.

“DeLorean Books & Publications,” DeLorean Directory.com.

Glenn Patterson, “John DeLorean: A Visionary or a Charlatan? Creator of ‘Back to the Future’ Car and His Belfast Factory Were Sources of Controversy,” Irish Times, Friday, January 8, 2016.

Lily Rothman, “The Short, Chaotic History of the DeLorean, Time, January 21, 2016.

“DeLorean Literature /DeLorean Magazines,” SpecialTauto.com.

2020 documentary film, DeLorean: Living the Dream (1hr, 21 min). Click for film.

____________________________________________________