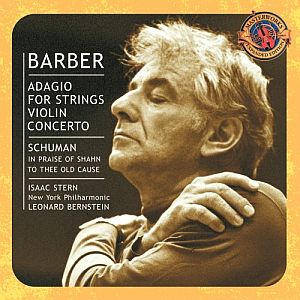

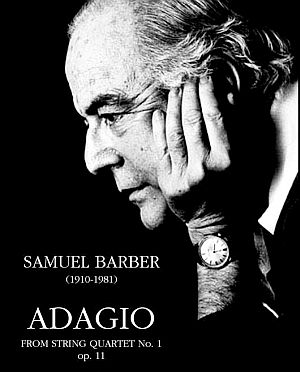

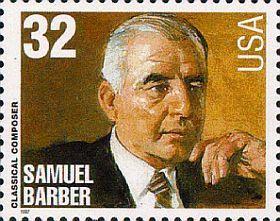

Samuel Barber, in later years, in sheet music cover photo for his Adagio from String Quartet No. 1. Click for digital.

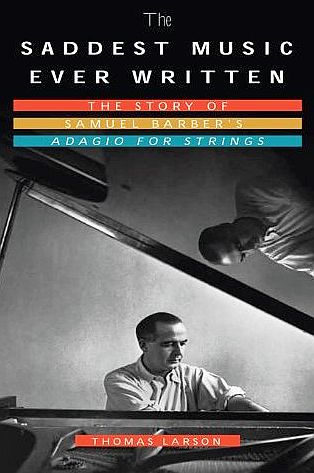

The music sample below – “Adagio for Strings” by Samuel Barber from 1936 – might also be called “Adagio for Tears” since it is known for evoking very powerful emotion and sadness among its listeners. In fact, a 2010 book by Thomas Larson on this classical piece is titled, The Saddest Music Ever Written. More on the book and its claim a bit later.

Music Player

“Adagio for Strings” – Samuel Barber

“Adagio for Strings” was reportedly one of President John F. Kennedy’s favorite pieces of music. In November 1963, on the Monday following JFK’s assassination, Jackie Kennedy had the National Symphony Orchestra perform the piece in his honor in a nationally-broadcast radio concert.

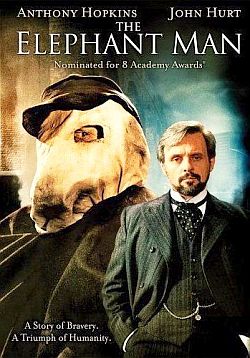

In recent years, “Adagio” has received more popular notice as many film goers have been moved to tears by the piece, used as powerful soundtrack music in productions such as: David Lynch’s Elephant Man of 1980, Gregory Nava’s El Norte of 1983, Oliver Stone’s Platoon of 1986, and George Miller’s Lorenzo’s Oil of 1992.

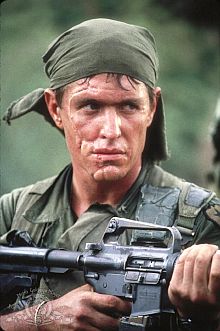

Poster for 1986 Oliver Stone film, “Platoon,” showing Sgt. Elias Vietnam death scene. Click for film.

In 2004, “Adagio for Strings” was voted the world’s “saddest piece of music” in one survey of listeners by BBC radio. The piece was also widely played in connection with events following the terrorist attacks of 9/11. In earlier decades, at the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in April 1945, the song was played extensively. In the current digital era, “Adagio for Stings” is among the most downloaded pieces of classical music. In 2006 a recorded performance of “Adagio” by the London Symphony Orchestra was the highest selling piece of classical music on iTunes. There have even been some disco, re-mix, electronic dance, and synthesizer versions of “Adagio” – which perhaps were not what Samuel Barber had in mind in 1936, but have nonetheless helped broaden the audience for this music. More on these later.

One of the most powerful and memorable uses of “Adagio for Strings” in a contemporary film score, comes in a scene from Oliver Stone’s Academy Award winning 1986 Vietnam War film, Platoon – a film sequence that seems to have had a particularly strong effect on a number of viewers. That scene is set in the jungles of Vietnam, as U.S. Army Sergeant Elias, played by Willem Dafoe, who is wounded and running to catch a departing helicopter during a firefight with the enemy. In this case, however, Elias – the “good U.S. soldier in Vietnam”– has been betrayed by his arch nemesis, Sergeant Bob Barnes, played by Tom Berenger – the “bad guy U.S. soldier in Vietnam.”

Elias and Barnes have been feuding throughout the story, and now in this jungle fire fight, Barnes shoots Elias believing he has killed him. But Elias is only wounded. Meanwhile, Barnes tells the others that Elias was killed in the NVA fire fight.

“Adagio for Strings” plays during the ensuing scene as the wounded Elias emerges from the jungle. He is literally running for his life from the pursuing NVA, trying to reach the helicopter. But he is too late, as the helicopter has already lifted off. As “Adagio” swells, the scene is viewed from both ground level and from above in the departing helicopter, as Elias’ platoon mates look down on the horrific scene. There alone, is Elias in a clearing, being pursued by a dozen or more NVA, then shot repeatedly, falling to his knees in a brutal death. “Adagio” continues playing throughout the ensuing slaughter and as the helicopter rises farther and farther away from the scene.

Actor Willem Dafoe plays U.S. Army Sgt. Elias in 1986 Vietnam War film, “Platoon.” |

Actor Tom Berenger plays “bad guy” Army Sergeant Bob Barnes in “Platoon.” |

One comment in an online forum at the website Oscar.net by film viewer Tim Anderson, describes his reaction to hearing “Adagio” in Platoon. He explains first that Stone had used the music earlier in the film – less noticeably and unnecessarily in Anderson’s view. But it is the Elias death scene with “Adagio” that really moves Anderson:

…When I first saw Platoon, I thought the use of Barber’s melancholic ode a bit overdone at the beginning. Indeed, I really don’t think it is necessary as an accompaniment to the new recruits getting off the airplane and entering “The Nam.” Perhaps Stone was attempting to depict the Vietnam conflict as a tragedy from the outset of the film. However, the use of the heavy strings of Barber, for me, overdid [it] …almost to the point of sentimentalizing the harsh reality of the war.

This changed later on, however. I am referring to the scene of Elias’ death. As he charges out of the jungle with virtually the entire NVA behind him, once again, the Barber Adagio is heard, swelling, till it is all we hear. No gunshots, screams, or helicopter blades; just the mounting intensity of this extremely spiritual work. The effect, to me, is completely unforgettable. Barber’s opus is already a completely emotional work, but to combine its sound with the image of goodness, of sanity in “The Nam” [i.e. Elias] being helplessly gunned down, is…well, indescribable. All I can say is, one must have no sensitivity at all not to find themselves emotionally weak during this sequence.

To be honest, I was never a huge fan of the Barber Adagio before seeing Platoon. That has changed; for me, the work is a virtual soundtrack to the tragedy of war…Vietnam, or any other. It has such a gripping, intense, spiritual feel to it…which is what makes it work so well for the moment of Elias’ death. To me, this scene is one of the most powerful sequences in any film I’ve ever seen. Mr. Stone deserves to be acknowledged for this brilliant teaming of sight and sound, one of the greatest in cinema history.

True, the Platoon sequence has especially powerful imagery, along with a compelling back story attached to specific characters, all of which make the music during the scene even more powerful. Yet even without the benefit of Hollywood imagery and story line, Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” historically, has had “stand alone” emotive impact on listeners from its earliest airings. So, how did this music come about?

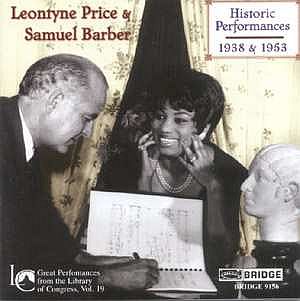

Samuel Barber in 1938. Photo, Library of Congress.

Samuel Barber was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania in 1910. At the age of seven he reportedly wrote his first music. As a 9-year-old he wrote a letter to his mother informing her that he did not want to play football or be an athlete, predicting that he “was meant to be a composer” — and adding that he was sure he would become one. When he was 10, Barber attempted to write his first opera, “The Rose Tree.”

At age 14, Barber entered the Curtis Institute of Philadelphia where he studied composition, voice, and piano, excelling in all three. Barber was one of the first students at Curtis in 1924, and it was there that he met his life-long friend, partner, and collaborator, Gian Carlo Menotti. The two friends became partners, bought a house together in New York state where they lived and worked for 40 years, although years later, they split apart. At 18, Barber won the Joseph H. Bearns Prize from Columbia University for his violin sonata, “Fortune’s Favorite Child,” since believed to have been lost or destroyed by Barber. In 1931, he wrote his first orchestral work, an overture to The School for Scandal, which premiered successfully in 1933 with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Alexander Smallens. A number of other commissioned compositions followed. In 1935, at the age of 25, he received a Pulitzer traveling scholarship which allowed him to study abroad.

Gian Carlo Menotti and Samuel Barber, circa 1930s.

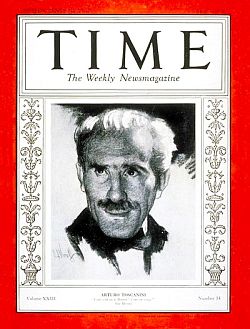

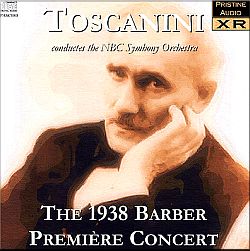

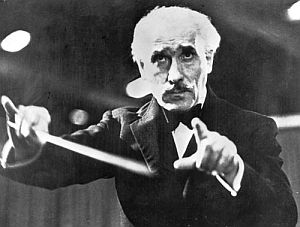

Toscannini

In those years, one of the most popular showcases for classical music was the weekly NBC classical music radio show from New York featuring the NBC Symphony Orchestra. The conductor for those performances dating from about 1937 was the famous Italian conductor, Arturo Toscanini, who had recently fled Mussolini’s fascism during World War II. Barber submitted his orchestral version of “Adagio for Strings” to Toscanini in January of 1938.

But when Toscanini returned the score to Barber without comment, Barber was annoyed and avoided the conductor, believing his work had been snubbed. But Toscanini sent word through a friend that he was planning to perform the piece and had only returned the score because he had already memorized it.

Toscanini, in fact, was impressed with Barber’s piece. “Simplice e bella”—simple and beautiful—were the words Toscanini used upon hearing his orchestra’s first rehearsal of Barber’s composition. This was high praise from a man who had become the single most important figure in classical music in America, but who rarely performed works by American composers. In fact, Barber’s “Adagio” would be the first American piece he performed on the NBC radio show.

Arturo Toscanini, the famous Italian conductor, at work.

“[O]n the one hand [Toscanini] is often considered the most dynamic, the most intense, the most powerful, overwhelmingly arresting conductor of his time. And overlooked in all of these reasonably accurate assertions is the fact that for all of the drama, for all of the power, for all of the intensity, he was also capable of wonderful delicacy and tenderness and gentleness. And he knew how to deal with a piece like this, which essentially is a very lyrical, gentle piece in so many ways, and present it directly and without – and this is the most important quality – without sentimentality, without excess, without making it sound overly sweet and cloying.” Toscanini also chose Barber’s “Adagio” for his first recording of American music.

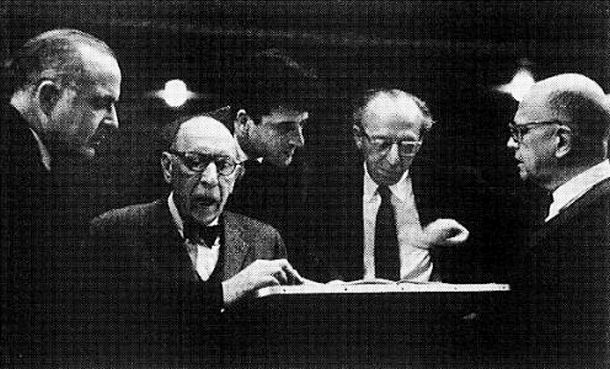

Samuel Barber, center, with Aaron Copland, left, and Gian Carlo Menotti, right.

Still, Barber’s “Adagio” went on to other performances, including a series of public performances, also on the radio, from Carnegie Hall in April 1942 by the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy. Both the Toscanini premiere performance of “Adagio for Strings,” and the Ormandy performance were captured on RCA Victor phonograph recordings.

Through the years, Barber’s “Adagio” has received the admiration and sometimes wonderment of other notable composers. Steve Schwartz, writing on Barber’s “Adagio” for Classical.net, has noted:

Composers like Aaron Copland, William Schuman, Roy Harris, and Ned Rorem – not all of them sympathetic to Barber’s music in general – look at this work and shake their heads, wondering how he pulled it off. They fall back on phrases like “finely felt,” “poetic,” “nothing phoney,” “a love affair.” There’s no real complication to the Adagio, no technique or unusual turn of harmony that holds the secret of its success. One cannot even pick one passage over another, any more than you can say one point makes the beauty of an arch. This is a masterpiece.

Mourning Music

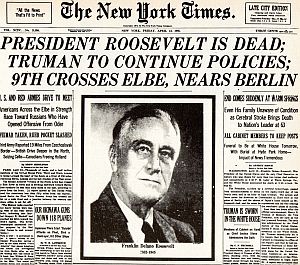

April 13, 1945: New York Times front page at the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

According to author Thomas Larson, radio producers began playing Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” over and over again, catapulting Barber to fame at a time when few knew him by name. “They knew Beethoven and Brahms but not Barber,” notes Larson.

Still, the playing of Barber’s “Adagio’ during the Roosevelt mourning period, says Larson, “began the piece’s long trek…[to]…cultural appropriation.”

In fact, “Adagio for Strings” would become something approaching official mourning music for fallen national leaders and other notable public figures – or as one account put it, a kind of “icon of the national soul.”

1945: Funeral cortege of President Franklin. D. Roosevelt in Washington, D.C.

“Adagio for Strings” was also played at the April 1955 funeral of Albert Einstein, and at Grace Kelly’s funeral in September 1982. Einstein, the brilliant theoretical physicist, was also a lover of classical music, and Kelly, an American Hollywood actress before becoming Princess of Monaco, had a tragic death in an automobile accident at age 52. Her televised funeral was attended by Hollywood stars and royalty from around the world. “Adagio for Strings” was also played several times over BBC radio in 1997 at the death of Princess Diana.

Mary Travers, of the 1960s’ folk group, Peter, Paul and Mary, had requested that “Adagio” be played at her memorial service. She died in September 2009 of leukemia. “Adagio” appears on the group’s final album, Peter Paul and Mary, With Symphony Orchestra. Alex Ross, music critic for The New Yorker, explaining in his 2007 book, The Rest is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century, that classical music in America “has not lost its binding power,” adding: “Whenever the American dream suffers a catastrophic setback, Barber’s Adagio plays on the radio.”

Agnus Dei

1941 photograph of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London during WWII blitz bombing; an image used with You Tube videos airing Samuel Barber’s “Agnus Dei.” Click for digital music.

Music Player

“Agnus Dei” – Samuel Barber

Among those recording the choral version have been, for example: The Corydon Singers in 1986; The New College Choir of Oxford, in 1997; the choir of Ormond College in 2000; the Robert Shaw Festival Singers in 2003, and others. The version in the Music Player below is by The Dale Warland Singers from their 1995 album Cathedral Classics.

Over the years, “Adagio for Strings” has become a fairly well-known piece, especially by those who follow classical music. And its trademark, even for the casual listener, is its emotional power. “You have to be a rock in the middle of nowhere not to have your gut wrenched out by this music,” said Ida Kavafian, a violinist and a Curtis Institute faculty member to New York Times reporter Johanna Keller in a March 2010 story on Samuel Barber’s centenary. Keller herself added: “…If any music can come close to conveying the effect of a sigh, or courage in the face of tragedy, or hope, or abiding love, it is this.”

Alexander Morin, author of Classical Music: Third Ear: The Essential Listening Companion, has noted that Adagio for Strings is “full of pathos and cathartic passion” and that it “rarely leaves a dry eye.” Others find the piece to be reflective, soothing, introspective and/or meditative. A few even find it celebratory at its climax. Tom Moon, writing in his book, 1,000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die, finds “Adagio for Strings” to be “a singularly moving eight minute journey suited to any introspective occasion.” Moon also observes that Barber’s Adagio is “alternately stormy and tranquil, with brooding counterlines that rise from the cellos and bases answered by hovering sustained notes from the violins…” Barber’s piece, he says, “creates its own atmosphere.” And one YouTube visitor, Gui Porto in 2015, among hundreds of those offering reaction to the various video postings of “Adagio for Strings,” noted: “There’s something about this piece that’s very hard to describe. It’s not just sad, nor melancholic, nor tearful. It sounds heavy and bleak, yet somehow enlightening, glorious… It almost needs a whole new adjective?”

|

“Elephant Man Scene” Film director David Lynch used “Adagio for Strings” in the final scene of his 1980 film, The Elephant Man. In comments to New York Times reporter Johanna Keller, Lynch described the music as “pure magic,” calling it “deeply spiritual and simply beautiful.” In The Elephant Man film, the story focuses on the life and struggles of John Merrick, who is so deformed he wears a hood in public to hide his face. Merrick, played by John Hurt, is exhibited as an “elephant man” circus curiosity, beaten by hooligans, and otherwise abused by society and assumed to be stupid and ignorant. A London Hospital surgeon, Frederick Treves, played by Anthony Hopkins, finds Merrick in the freak show where he is brutishly managed. Treves is curious about Merrick’s medical condition, and eventually pays off the freak show manager for Merrick, and brings him to his hospital for research purposes. Still assumed to be ignorant, and viewed as repulsive by hospital staff, Merrick at one point astonishes Treves and the hospital administrator by reciting the 23rd Psalm from memory. Turns out that Merrick is quite articulate and intelligent. Although bound mostly to his hospital room, Merrick occasionally dines with Treves and his family and later receives high society guests, including the famed actress Madge Kendal, played by Anne Bancroft. At one point, Merrick is kidnapped by his former side show manager and put back in the freak show business in Europe, before he is rescued by Dr. Treves and returned to his hospital room. There he mostly reads and works on building a scale-model of a cathedral he can see from his hospital window.  “Elephant Man” John Merrick at right receiving audience ovation during night at the theater before his final “sleep” scene when Barber’s “Adagio” is movingly used. Near the end of the film Mrs. Kendal has arranged a special evening for Merrick – an evening at the musical theater, attending in white tie and seated in the Royal Box. At the conclusion of the production that evening, Mrs. Kendal takes to the stage after the final curtain and announces to the entire audience that she and the musical company have dedicated the evening to a lover of the theater, Mr. John Merrick, motioning to him in the Royal Box. And with that, the entire house breaks into applause. As Merrick stands to acknowledge the recognition, the house audience then rises in a standing ovation for Merrick. Later that night, back at his room, Merrick thanks Dr. Treves for all he has done, and then prepares to retire. Merrick then puts the final touches on his exquisitely done cathedral scale model, signing his name to the model’s base. He then begins to prepare himself for bed, though this time, removing the pillows that have allowed him to sleep in an upright position so he will not die from the weight of his head. He lies down on his bed, knowing he will die, consoled by a nearby photograph of his mother, recalling her quoting Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem, “Nothing Will Die.” Barber’s “Adagio” plays quietly in the background during the final bedroom scenes as Merrick prepares to lay down to die. |

Saddest Ever?

Cover of Thomas Larson’s 2010 book, “The Saddest Music Ever Written: The Story of Samuel Barber's ‘Adagio for Strings’,” showing Barber at a piano in the 1930s. Click for book.

The Adagio is a sound shrine to music’s power to evoke emotion. Its elegiac descent is among the most moving expressions of grief in any art. The snail-like tempo, the constrained melodic line, its rise and fall, the periodic rests, the harmonic repetition, the harmonic color, the uphill slog, the climactic moment of its peaked eruption – all are crafted together into one magnificent effect: listeners, weeping in anguish, bear the glory and gravity of their grief. No sadder music has ever been written.

In an interview with New York radio station WQRX after his book came out, Larson explained: “…To me, Barber did something as a composer in the composition of sorrow that really tops the list… I myself don’t hear anything but the purifying of this emotion in this piece of music. There’s no other thing to call this piece but sad. It’s a lament and an elegy.”

In addition to Larson’s book, others have written extensively about Barber and his work, and a number of academic analysts have also dissected Barber’s “Adagio” from one perspective or another, several probing the music’s uses and reception in popular culture. Among books on Barber’s music and his life are: Samuel Barber: The Composer and His Music by Barbara B. Heyman (1993); Benjamin Britten & Samuel Barber: Their Lives and Their Music by Daniel Felsenfeld (2005); Samuel Barber Remembered: A Centenary Tribute, by Peter Dickinson (2010); and, Samuel Barber: A Research and Information Guide, by Wayne Wentzel(2010). See also “Sources” below for additional works and references.

BBC Listeners

Samuel Barber at ease, in a relaxed moment, undated.

Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” (52.1%)

Henry Purcell’s “Dido’s Lament” (20.6%)

Gustav Mahler’s Adagietto, from 5th Symphony (12.3%)

Billie Holiday’s “Gloomy Sunday,” by Rezsô Seress (9.8 %)

Richard Strauss’s “Metamorphosen” (5.1 %)

In addition to the“saddest music” candidates above, others also mentioned elsewhere include: Chopin’s Funeral March, Maurice Ravel’s Pavane for a Dead Princess, Rachmaninoff C#-minor Prelude, Albinoni’s “Adagio,” Arvo Pärt’s “A Far Cry,” Benjamin Britten’s “Cantus in Memoriam,” Vaughan Williams’ “Variations on a Theme by Thomas Tallis,” and the slow movement in F-minor of Mozart’s F-major piano sonata, K.280. Still, “Adagio for Strings” – at least by popular count and sentiment in the 2004 BBC radio survey – appears to be the “winner” in the saddest music category.

Samuel Barber U.S. postage stamp issued in 1997.

Barber died of cancer at the age of 71 in 1981 in New York and is buried in West Chester, Pennsylvania next to his parents and sister. Additional stories at this website on the use of poignant and moving music in film and television productions include, for example: Bruce Springsteen and Neil Young songs in the film, Philadelphia; Carly Simon’s “Let The River Run,” used in Working Girl; Bill Conti’s song, “Philadelphia Morning” and others used in the first Rocky film; and the 2006 song, “Life is Beautiful,” by Vega 4, used in Grey’s Anatomy and other TV and film scores. For additional stories at this website on the history of music and its impact on culture, see the “Annals of Music” category page, or visit the Home page for other choices.

Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 12 December 2013

Last Update: 23 January 2022

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “The Saddest Song: 1936-2103,”

PopHistoryDig.com, December 12, 2013.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Samuel Barber at age 28 in 1938, the year “Adagio for Strings” was featured by Toscanini on NBC Radio. |

“U. S. Composer Gets Toscanini’s Approval,” New York Times, October 27, 1938.

“This Day in History – November 5, 1938: Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings Receives its World Premiere on NBC Radio,” History.com, 2012.

Olin Downes, “Toscanini Plays Two New Works; Two by Barber, American Composer, ‘Adagio for Strings’ and ‘Essay for Orchestra’ Third by Paul Graener Dvorak’s ‘New World’ Symphony, and Debussy’s ‘Iberia’…,” New York Times, November 6, 1938, p. 48.

Nathan Broder, “The Music of Samuel Barber,” The Musical Quarterly (Oxford University Press), Vol. 34, No. 3, July 1948, pp. 325-335.

Nathan Broder, Samuel Barber, New York: G. Schirmer, Publisher, 1954, 111pp.

Barbara B. Heyman, Samuel Barber: The Composer and His Music, Oxford University Press, 1st Edition, 1992, 608 pp.

Steve Schwartz, “Samuel Barber: Adagio for Strings, Op. 11,” Classical.net, 1995.

“Vote for the World’s Saddest Music,” BBC Radio 4, last update, May 2004.

“Samuel Barber,” Wikipedia.org.

“Adagio for Strings,” Wikpedia.org.

Luke Howard, “The Pop Culture Repercussions of of Samuel Barber’s Adagio For Strings,” First International Samuel Barber Symposium, Richmond, Virginia, March 23, 2001.

Daniel Felsenfeld, Benjamin Britten & Samuel Barber: Their Lives and Their Music, Amadeus Press, 2005, 180 pp.

“The Impact of Barber’s ‘Adagio for Strings’,” National Public Radio, November 4, 2006.

Luke Howard, “The Popular Reception of Samuel Barber’s Adagio For Strings,” American Music, Spring 2007. pp. 50-80.

Alex Ross, The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century, Macmillan, October 2007, 624 pp.

Julie McQuinn, “Listening Again to Barber’s Adagio for Strings as Film Music,” American Music, Volume 27, Number 4, Winter 2009, pp. 461-499.

Christopher Kilian, “Happy Belated Birthday, Samuel Barber,” Examiner.com, March 12, 2009.

Johanna Keller, “An Adagio For Strings, And For The Ages,” New York Times, March 7, 2010.

“Agnus Dei (Barber),” Wikipedia.org.

Brian Wise, “ Barber’s Adagio: The Saddest Piece Ever?,” WQXR.org (New York Public Radio), Wednesday, September 8, 2010.

WQXR Features, “9/11: Music of Reflection and Resilience,” WQXR.org (New York Public Radio), Wednesday, September 8, 2010.

Peter Dickinson, Samuel Barber Remem- bered: A Centenary Tribute, Univer- sity of Rochester Press, 2010, 214 pp.

Wayne Wentzel, Samuel Barber: A Research and Information Guide, Routledge Music Bibliographies, 2010, 448 pp.

Thomas Larson, “The Saddest Music Ever Written: The Story of Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings’,” ThomasLarson.com, 2012.

Noah Adams, “The NPR 100: ‘Adagio for Strings’,” National Public Radio, February 23, 2012 / March 13, 2000.

“Oliver Stone: Interactive,” OscarWord.net, December 2012.

David Lynch’s The Elephant Man ’80 ~ “Nothing Will Die” (Finale), YouTube.com (11:16).

Melinda Bargreen, “’The Saddest Music Ever Written’: Samuel Barber’s ‘Adagio for Strings,’ Deconstructed” (Book Review), Seattle Times, Thursday, December 2, 2010.

“American Composer Samuel Barber,” Gay Influence, Thursday, July 21, 2011.

“Samuel Barber – Agnus Dei [HD],” YouTube.com, Uploaded by The Jazz Room, June 1, 2011.

“Samuel Barber: Agnus Dei (Adagio for Strings),” YouTube.com, Uploaded by lee32 uk, The Choir of Trinity College, Cam- bridge, UK.

“Samuel Barber, Composer,” Singers.com.

“The Elephant Man”(film), Wikipedia.org.

Jack Fishman/San Antonio Symphony, “Barber Sneaks Up on You,” MySanAntonio .com, November 12, 2010.

Composers' Row: From left, Samuel Barber, Igor Stravinsky, Lukas Foss, Aaron Copland and Roger Sessions – all assembled, it is believed, in honor of Stravinsky at New York City’s Town Hall on December 20, 1959.