A John Hancock Life Insurance Co. ad on the art of Frederic Remington appeared in “Life” magazine Sept. 21, 1959.

The Hancock company ran scores of such ads, sometimes venerating notable scientists, inventors, politicians, business leaders, military men, or historic events. In other similar ads, the company paid homage to unsung heros, or those who did the daily labors or provided key services, such as the Maine lobster men, an un- known “back bench” Congressman, or the family doctor. To be sure, the Hancock Co. was basking in a positive light for telling these tales, especially those of the more popular figures. Still, all in all, these were classy pieces of advertising; often done with a handsome original color illustration using known and unknown artists. They appeared only once or a few times at most in the magazines of the day. Consequently, original copies of these ads today are regarded as collector’s items, often showing up at auction houses or on E-bay.

The John Hancock ad above, for example, tells the story of Frederic Remington, the famous artist of the American West. This ad appeared, for example, in the September 21, 1959 issue of Life magazine, the cover from that issue shown below. The sidebar that follows next includes the full text of the John Hancock Remington ad. Following that is a little more history on Frederic Remington, a short profile of the John Hancock company, and some reaction to the company’s “historical figures” advertising campaign.

|

“He gave us the wild Old West for Keeps…”

“There are plenty of people who’ll tell you the Old West is deader than a wooden Indian. But they’re forgetting about a red-faced rock of a man named Frederic Remington. Fred showed up in the West one day looking for fame and fortune. And wherever he looked, the West spread riches before his eyes. Her untamed land. Her rowdy people. Her dust and gunsmoke and sweat. Fred liked what he saw…. …Looked like pretty soon, there wouldn’t be any West. Fred figured he’d better do something quick. So he started right there… Then he happened to look over his shoulder. Thunderation! There was the railroad coming after him. And there were men, in mail-order clothes, putting up fences, so they wouldn’t need cowboys anymore. Looked like pretty soon, there wouldn’t be any West.  Life, Sept 21, 1959. He’d spread a pack of Comanches across a canvass, so mean-looking and so real you’d want to turn and run for it. Then he’d take a horse and transfer him to paper, still bucking and kicking fit to kill. Fred didn’t miss an inch. Through states that hadn’t even been named yet he went, getting it all down, before it was too late. The pictures hang in museums now, but the story they tell about the wide open, rip-roaring man’s kind of place belongs to all of us. That’s the way Fred wanted it.” John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance [across bottom of the ad page, in lower point italic, ran the Hancock pitch] Ask Your John Hancock Agent about our Signature Series – the most advanced life insurance contracts for every need. |

Frederic Remington

Frederic Remington’s “The Great Beast Came Crashing to The Ground,” shows hunter shooting a buffalo. Click for wall art.

Frederic Remington’s 1892 watercolor shows buffalo hunter spitting shot balls into a rifle rather than dismounting to use a ramrod. Click for wall art.

During his travels Remington worked as cowboy, ranch hand, lumberjack, hunted grizzly bears in New Mexico, and became a gold miner in Apache country in Arizona. He also tried other ventures, including sheep ranching in Kansas and as part-owner of a Kansas City saloon. Other government and business ventures lasted only a few months in some cases. But along with his travels and experiences, he continued to draw. He sent illustrations back East to newspapers and magazines, among them, Outing Magazine, Harper’s Weekly and Scribners. Reming- ton’s work hit the market at a good time, as tales of the West were very popular in Eastern cities. Publishers used everything he sent.

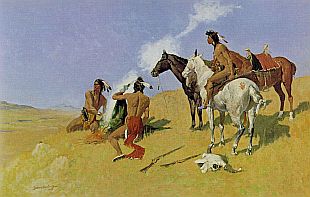

Frederic Remington’s “The Smoke Signal,” 1905, oil on canvas. Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, TX. Click for art print.

In 1895, he became enamored of sculpting, and without formal training immersed himself in the process. Remington had been fascinated by the motion of horses and used one of the early roll-film box cameras to take numerous photos of horses, among other subjects, to study them. He painted and sculpted the animals often, some at full gallop, usually placing them with human figures. In his sculpting, he produced a clay piece he called “the broncho buster,” with rider holding on to the wild horse as it reared up on its hind legs — not an easy subject for a beginning sculptor, in any case. Within several months of this undertaking, he had a plaster cast made, then bronze copies, which were later sold at Tiffany’s, earning him a decent return. However, some critics disparaged his work, calling it “illustrated sculpture.” History was kinder, as Remington’s “Bronco Buster” would become a famous piece of Western “cowboy” sculpture.

A Frederic Remington cover for the Saturday Evening Post, 1901.

Remington also made other travels abroad to North Africa, Mexico, Russia, Germany and England.

By 1901, Collier’s magazine was buying Remington’s illustrations on a steady basis and his work also appeared in other magazines, such as the Saturday Evening Post, a sample of which appears at right. He also published a couple of novels in the early 1900s and had one made into a stage play.

Around 1904, Remington decided he would quit writing and illustration to focus on sculpture and painting. In 1905, he received a commission for “The Cowboy” sculpture from the Fairmont Park Art Association, in Philadelphia. That work still stands today in East Fairmont Park, as shown below.

Frederic Remington’s “The Cowboy,” a large 1908 statue that stands today in Philadelphia, PA’s Fairmont Park. Click for sculpture.

The financial panic of 1907 caused a slow down in the sales of Remington’s works, and he and his wife later moved to Ridgefield, Connecticut, where he died suddenly in December 1909 from a ruptured appendix. He was only 48 years-old at the time and still in the prime of his career.

During Remington’s short lifetime, he produced some 3,000 paintings, not all of which survived, as he burned some when vowing to quit illustration. He also created about 25 bronze sculptures, the most famous being “The Bronco Buster,” and the largest, “The Cowboy” in Philadelphia. Today, Remington stands out as one of the most successful Western illustrators from the “Golden Age” of illustration in the late 1880s-early 1900s period. He is also often cited at the inventor of “cowboy” sculpture.

John Hancock, Inc.

The John Hancock company logo as seen in 2010.

John Hancock’s advertising and image-making, meanwhile, has its own interesting history. In the 1860s, an early president of the company installed 1,000 tin signs at railroad depots and grocery stores touting the company’s business. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, John Hancock agents went door-to-door throughout America retailing their policies, collecting premiums and passing out booklets on American history. And during 1940s-through-1950s period, its advertising “stories” — such as the one on Frederic Remington — could be found in mainstream magazines of those years.

Hancock’s Ad Series

Baseball great Babe Ruth was another of the famous figures featured in the John Hancock ad series.

“Next time somebody asks you, “Does fine art have a place in advertising?” — show them the John Hancock Life Insurance campaign. Rarely in the history of advertising has a campaign more consistently held to the fine arts level. Rarely has one achieved more favorable recognition for the advertiser. These messages have been hung in schoolrooms, factories, and offices. Reprint requests have run into hundreds of thousands. Statesmen have commended them; citizens have been stirred by them. They have won awards. And they purchased readership at well below average cost for the insurance field. We see a moral in all this. It proves, we think, that everything which has the power to move people has a place in advertising’s kit of tools. The art of the cartoon belongs; so does the art of the museum; and so does every form of artistic expression in between. The craft of the art director lies in being able to pick, from his broad workbench of persuasion, the right tool for the job every time.”

See also at this website, “Christy Mathewson, Hancock Ad: 1958,” another from the John Hancock advertising series. See also the “Print & Publishing” category page for other story choices on the history of magazine publishing, magazine cover art, and politics and publishing. Additional story selections can be found at the Home Page or the Archive. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

______________________________

Date Posted: 23 November 2010

Last Update: 15 February 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Remington’s West, Hancock Ad:1959,”

PopHistoryDig.com, November 23, 2010.

________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance Co. Advertisement, “He gave us the wild Old West for Keeps…,” Life magazine, p.15.

“What is ‘Illustration’ and Why Does It Irritate the Intelligentsia So?,” AmArtArchives.com.

Ben Stahl and the art directors of McCann-Erickson, Inc., “Does it Belong?,” 1949 magazine advertisement.

“Biography for Frederic Remington,” Ask Art.com.

“Fredric Remington,” RemingtonArt.com.

“Frederic Remington,” Wikipedia.org.

Frederic Remington Art Samples, at: AskArt.com.

In 1991 the PBS series American Masters filmed a documentary of Remington’s life called Frederic Remington: The Truth of Other Days produced and directed by Tom Neff.

Peggy Samuels & Harold Samuels, Frederic Remington: A Biography, Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co.,

Frederic Remington, Buffalo Hunter Spitting a Bullet into a Gun, 1892, FredericRemington.org.

Frederic Remington (writer & illustrator), “A Scout with the Buffalo Soldiers,” (slightly abridged version) The Century, Vol. 37, No. 6, April 1889.

Brian Dippie, “Remington’s Kodak Moments,” TrueWestMagazine.com, September 1, 2007.

“John Hancock Insurance,” Wikipedia.org.

John Hancock Financial website.

“Western Images by Frederic Remington,” PhilaPrintShop.com.

______________________