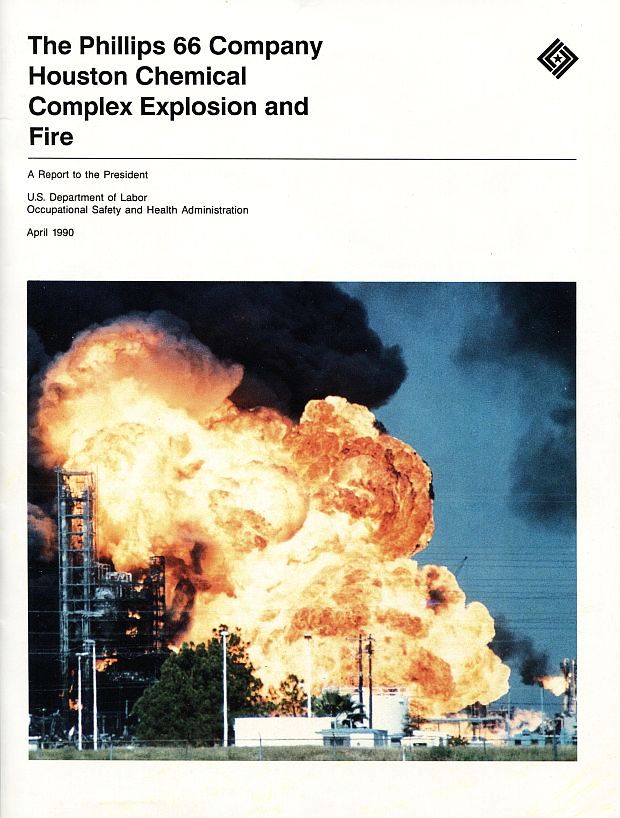

On October 23rd, 1989 an earth-shattering explosion at the Phillips Petroleum Company’s plastics plant in Pasadena, Texas, killed 23 workers, injured more than 130 others, and totally destroyed the plant, resulting in some $750 million to $1 billion in economic losses. The explosion, with the force of 2.4 tons of TNT, ripped through the plant, twisting multi-story steel structures like tinker toys, sending debris into the air for miles. Buildings shook in downtown Houston and homes were damaged eight-miles away.

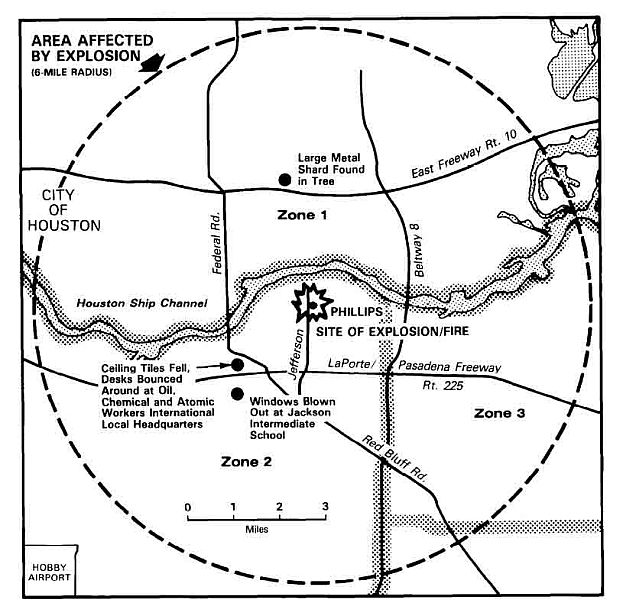

October 23, 1989. Fire and smoke at Phillips Petroleum’s Pasadena, Texas plastics plant, following explosion that would kill 23 workers and injure more than 130 others. Homes were damaged within an 8-mile radius of the blast. (AP Photo/Ed Kolenovsky)

“Everything shook with that tremendous boom, and then it began raining pieces of sheet metal a foot more more longer,” reported construction worker Mike Buchanan in comments to the New York Times. Buchanan was driving on Interstate 10 at the time of the explosion, about five miles from the plant. The smoke cloud rising from the disaster could be seen at a distance of 15 miles. Yet the seeds of this catastrophe, according to many experts in and out of the industry, were planted some years before, owing mostly to business and market machinations on Wall Street, as well as the company’s adjustments to those pressures. More on that part of the story in a moment; first some company background.

October 24, 1989. Early reporting and headline on the Phillips explosion from the New York Times before final numbers were determined on those killed and injured.

Phillips History

In the early 1900s, brothers Frank and L.E. Phillips were having success as wildcat operators and by June 1917, they formed the Phillips Petroleum Company in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. It soon became a fully integrated oil company with oil and gas production, crude oil pipelines, refineries, and gasoline marketing. After discoveries Texas and Kansas, Phillips became a leader in natural gas production, and by 1925, it was the largest U.S. producer of natural gas liquids.

The Phillips 66 logo and service station sign, having the look, in part, of the “Route 66" highway sign.

With World War II, Phillips became a producer of high-octane aviation fuel and jet fuel, and after the war, it moved into petrochemicals. Forming the Phillips Chemical subsidiary, it first entered the fertilizer business, but soon stumbled into plastics when a couple of its chemists in 1951 accidentally came up with Marlex, crystalline polypropylene chemical that could be used for a variety of plastics.

Initially, there were few uses for the substance until a company named Wham-O came along in 1958 with a plastic, waist-twirling “Hula Hoop” toy that became a pop culture sensation. Wham-O would sell hundreds of millions of Hula Hoops, many made with Phillips’ Marlex polypropylene. As the Hula-Hoop fad diminished, Wham-O continued using Phillips’ Marlex through the late 1960s and beyond to make the plastic Frisbee, a recreational throwing disc that also became popular. Phillips Chemical by then was making all kinds of plastic products.

Late 1950s. Phillips Chemical began to make its mark as a plastics producer with rise of the Hula Hoop.

“Almost anything can be made of Marlex…,” Phillips explained in a two-page magazine ad showing a happy family with all kinds of plastic products arrayed around them. “…And 1,001 things are, from colorful, stain-proof fabrics to tough-boy resistant school furniture. They’re easy to use, clean and carry. Easy to look at too. Not surprising then that Marlex is a new household word…”

Well, perhaps not a household word, but by then certainly contributing millions of dollars to Phillips’ coffers.

Back in the oil and gas business, meanwhile, Phillips had ventured internationally with exploration in Canada, Venezuela, and Colombia, and made a major North Sea gas discovery in 1969. In the 1970s, the company was rocked by political scandal for illegal campaign contributions, but by then it had become giant multinational corporation. The Phillips empire by 1979 included 8,400 miles of pipelines, nine crude oil tankers at sea, five U.S oil refineries, 14 chemical plants, and 13,600 service stations. In 1983 it acquired the General American Oil Company, “one of the largest independent oil companies in the nation, with worldwide operations and interests.” By the mid-1980s, Phillips was among the top tier of Fortune 500 companies with annual sales north of $10 billion and profits of more than $1 billion.

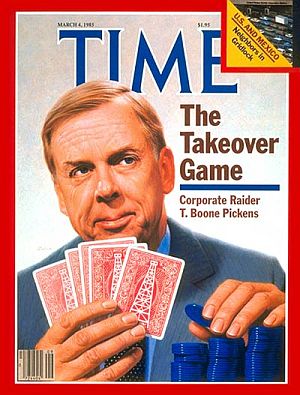

March 1985. T. Boone Pickens on the cover of Time magazine in feature story, “The Takeover Game.” Click for his book.

The Raiders

The mid-1980s, however, would not be happy times for Phillips Petroleum or Bartlesville, Oklahoma, the company’s headquarters. That’s when corporate raiders T. Boone Pickens and Carl Icahn came knocking on Phillips shareholders’ doors, attempting to buy out the company in successive takeover attempts. First, came T. Boone Pickens.

In December 1984, Pickens led an investment group named Mesa Partners in an attempt to purchase what was then the nation’s eighth-largest oil company.

Pickens, a 1951 graduate of Oklahoma State University with a degree in geology, had worked for Phillips in one of his first jobs in the oil industry. But he later became a wildcat oilman, and by 1956 founded the company that would become Mesa Petroleum.

By 1981, Mesa had grown into one of the largest independent oil companies in the world and Pickens would use its Mesa Partners investment group as the vehicle in his shareholder raids. Pickens, like other raiders of that period, saw his takeover bids as helping to sharpen the target corporations, ultimately, in his view, increasing their value and making them better companies – a view not always shared by the companies under attack.

Pickens had previously made a run at Gulf Oil. In the Phillips raid, Pickens accumulated 8.9 million shares of Phillips stock by November 1984 and was angling for another 23 million shares, which would have given him 21 percent of the company. On December 2nd, 1984, Phillips executives were told that Pickens’ Mesa group was making a tender offer at $60 a share — $12 more per share than the stock was then selling for. Pickens said the offer was the first step in a leveraged buyout of Phillips. While just a fraction the size of Phillips, Pickens and Mesa’s leveraged offer was worth $1.38 billion.

Cartoon poking fun at Pickens’ buyout bid for Phillips. Dave Simpson, Tulsa Tribune, December 1984.

But people in Bartlesville began to fear that a takeover would mean job cuts. Some pulled their savings from local banks and a few small businesses began backing out of deals. Layoffs were feared, and holiday shopping that December was subdued.

But townspeople also picketed, wrote anti-Pickens songs, sold “Boone Buster” T-shirts, and held Phillips rallies. Pickens buyout plan was for all of Phillips’s stockholders to receive the equivalent of $60 a share. On that basis, Phillips’s 154.3 million shares would be worth at least $9.3 billion. But Pickens later withdrew his bid after settling with the company. Within a month of Pickens’ December 1984 raid, Phillips` reached a compromise with him, issuing a recapitalization plan to increase the company’s stock value. Under the plan, Phillips would buy back 38 percent of the 154 million shares outstanding at $53 a share, or $3.1 billion. But that wasn’t the end of Phillips’s troubles.

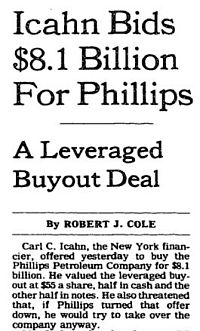

Feb 1985. New York Times headlines for story on the Icahn raid at Phillips.

He made his run at the company in February 1985, challenging some of the terms in the Pickens agreement, and putting together an $8.1 billion takeover bid. On February 12th, Icahn sought to buy up 45 percent of the company, which combined with the 5 percent he already owned, would give him a controlling stake in the company.

In early March, Phillips executives, faced with shareholders willing to sell to Icahn, came up with a plan to exchange debt securities for half of its outstanding stock, including Icahn’s 5 percent, at $62 per share – compared to the $53 per share it had paid Pickens. Icahn accepted the deal and he left a wealthier man.

In the end, Phillips had managed to outflank both Pickens and Icahn, essentially out-bidding them with sweeteners and special deals for stockholders. But the price was high. Pickens made $90 million in his deal; Icahn $50 million. And in the process, Phillips – with lots of new debt – became the banker’s new best friend. But how this maneuvering and financial debt would manifest itself on the ground, in day-to day operations at the company’s oil and chemical plants, was the more dangerous story.

Debt & Job Cuts

By year end 1985, Phillips was $8.6 billion in debt, and its stock value had fallen dramatically. In 1986, the company’s earnings plunged 45 percent. Under Wall Street’s watchful eye, the company began looking for ways to reduce debt, keep production up, and bolster returns. It soon began selling off some assets and cutting jobs. Between 1984 and 1987, it cut more than 7,000 jobs, and was still slashing in 1989.Between 1984 and 1987, Phillips cut more than 7,000 jobs, and was still slashing in 1989. But some of those job cuts might prove to be costly.

“The stock buyback scheme [ to fend off Pickens and Icahn] forced Phillips to let go 10,000 of its 25,000 employees,” wrote Joseph Kinney, executive director of the National Safe Workplace Institute in Chicago in an October 1989 Op-Ed piece. “…Among those terminated were safety engineers, industrial hygienists and maintenance engineers — technicians who are integral to plant safety.” Bob Wages of the Oil, Chemical & Atomic Workers Union (OCAW) would also note: “Many of the job cuts (at Phillips) came as a result of closures and divestitures, and others as a result of early retirement offers… Seasoned employees at all levels were let go. In fact, the ranks of hourly workers were decimated — once by early retirements and twice by substitution with contract employees….”

One of the places where strains in the Phillips’ workforce soon became apparent was at the company’s Pasadena petrochemical plant near Houston, where polyethylene plastic was produced. Built in 1956, the Houston Chemical Complex in Pasadena, Texas had undergone major expansions in the late 1970s and 1980s.Phillips froze its work force and used outside workers and mandatory overtime to run the plant. The plant produced approximately 1.5 billion pounds high-density polyethylene (HDPE) per year, a plastic material then used to make milk bottles and other containers. Some 1,500 people worked at the facility, including 905 company employees and approximately 600 daily contract employees who were engaged primarily in regular maintenance activities and new plant construction. But in the aftermath of the mid-1980s takeover raids, the company froze its work force there and used a combination of outside workers and mandatory overtime from existing workers to run the complex. Some workers on mandatory overtime, for example, were doing five-day, 12-hour-per-day shifts in 1989. At the Pasadena plant, Phillips also froze its maintenance work force at about 140-150.

Still, with production up, Phillips had ongoing maintenance responsibilities, especially in the ethylene reactors where production would be slowed by bad product blockage. These maintenance needs were met, increasingly with outside contractors through the services of Fish Engineering. By 1989, there were more than 200 such contract laborers performing maintenance tasks at the plant.

Cheaper Labor

“The company is strongly motivated to subcontract,” explained OCAW’s Robert Wages at November 1989 a Congressional hearing, “as these workers have no labor agreement and can be compensated at approximately 65 percent of that of a Phillip’s employee.” Contract laborers were cheaper in other ways too: benefits did not have to be paid, nor medical insurance or pensions. Nor did the company have to worry about payroll, accounting, hiring or firing. The subcontractor did all that.

Stock photo of construction workers. In the aftermath of the 1989 Phillips plastic plant explosion, an examination of the differences in experience and training between long-time company and union employees vs. hired-out contract workers was revealed to be an important issue, with contract workers’ inexperience implicated in the explosion.

But contract workers did not always receive the level of training that full time laborers did — particularly with regard to hazardous material and emergency procedures. In fact, a 1990 study commissioned by the U.S. Occupational, Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and conducted by the John Gray Institute of Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas would conclude: “Compared to permanent employees, contract employees receive significantly less safety and health training and are less knowledgeable about workplace hazards, hazardous materials, and emergency response in petrochemical facilities.”

And that just might have been what made the difference on October 23, 1989. That’s when explosions ripped through the plant, killing and maiming workers, and terrorizing residents for miles around the facility. One OCAW official, reacting to the explosion in November 1989 was quoted in the AFL-CIO News stating that “contracting out of maintenance work, elimination of relief crews, excessive overtime, and paring of staff to the ‘bare bones’ set the stage for an explosion that was waiting to happen.”

Cover of the April 1990 U.S. Department of Labor/OSHA report to the President showing enormous fireball at the October 1989 explosion of the Phillips 66 plastics plant in Pasadena, TX that killed 23 workers.

The primary cause of the explosion was the accidental release of a mixture of 85,000 pounds of four highly flammable process gases that created a vapor cloud which then moved rapidly from an open valve to an ignition source on the plant grounds. At the time of the accident, a Fish Engineering contracting crew was working on what is known as a settling line or dump leg, in which solidified polyethylene from processing — called “plugs” or “logs” — accumulates as blockage and must be removed in a normal maintenance procedure. “We were working on No. 1 leg…,” Phillips worker, Chuck Soules would later recall. “The crew that they had there at the time, as far as contractors, was very inexperienced. They did not know what was going on.”

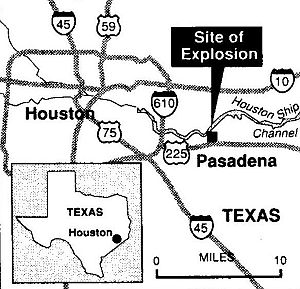

Map showing plant location.(New York Times).

…Because of the high operating pressure, the reactor dumped approximately 99 percent of its contents in a matter of seconds. A huge unconfined vapor cloud formed almost instantly and moved rapidly downwind through the plant.

…Within 2 minutes, and possibly as soon as 90 seconds, the vapor cloud came into contact with an ignition source and was ignited. Two other major explosions occurred subsequently, one about 10 to 15 minutes after the initial explosion when two 20,000 gallon isobutane storage tanks exploded, and another when another polyethylene plant reactor catastrophically failed about 25 to 45 minutes into the event…

…The large number of fatally injured personnel was due in part to the inadequate separation between buildings in the complex. The distances between process equipment were in violation of accepted engineering practices and did not allow personnel to leave the polyethylene plants safely during the initial vapor release; nor was there sufficient separation between the reactors and the control room to carry out emergency shutdown procedures. The control room, in fact, was destroyed by the initial explosion. Of the 22 victims’ bodies that were recovered…, all were located within 250 feet of the vapor release point; 15 of them were within 150 feet.”

“Area Affected By Explosion” map shows a six-mile radius area around the site of the Phillips November 1989 explosion with some examples of building damage and debris that followed.

When Secretary Dole announced the proposed fine for Phillips in April 1990, she explained: “This tragedy is magnified by clear evidence that this explosion was avoidable, had recognized safety procedures been followed. OSHA has uncovered internal Phillips documents that called for corrective action but which were largely ignored.” In fact, there were signs as early as 1987, and up until a few weeks before the explosion, operations at the Phillips plant weren’t as tight as they should have been.

U.S. Secretary of Labor, Elizabeth Dole, shown at another event, would issue OSHA’s April 1990 report to the President on the Phillips explosion.

In April 1989, an OSHA inspector had received complaints about mandatory overtime from some Phillips employees. A few months prior to the explosion, a crew of contractors working at the plant had suggested to horrified plant operators that they use reactor pressure to clean a 10-inch valve that had become plugged. And in August (1989), Fish Engineering sub-contractors opened some piping to a tank without isolating the line, resulting in a venting of flammable solvents and gas into an adjoining work area where it ignited, burning four workers and killing two others. OSHA cited Phillips for improper lock-out procedures and proposed a fine of $720, which the company contested.

But after the plastics plant calamity at Pasadena, OSHA proposed that Phillips be hit with a $5.7 million fine, accusing the company of 566 willful safety violations, defined by OSHA as “those committed with an intentional disregard of, or plain indifference to, the requirements of the Occupational Safety and Health Act.” OSHA also issued 181 willful and 12 serious violations for subcontractor Fish Engineering along with $729,600 in fines. However, in 1991, Phillips reached a settlement with OSHA removing the “willful” characterization of the violations and eventually agreed to pay $4 million to settle the charges, less than 2 percent of the company’s profits in the year of the accident.

Photo of the damaged, still smoldering Phillips plastics plant in the aftermath of the 1989 explosions and fire.

Hazardous Industry

Dangers Rising

“OSHA’s findings in the investigation of the Phillips complex disaster,” said the agency’s April 1990 Report to the President, “support the conclusion that poor risk assessment and management, lack of redundant systems and fail-safe engineering, inadequate maintenance of equipment, poorly conceived operational or maintenance procedures, and incomplete employee training are the underlying factors that contribute to or heighten the consequences of an accident.” And OSHA also warned: “Because of the trend toward larger, continuous operations, the hazards within this industry are being magnified…”

The Phillips explosion, in fact, was not an isolated case – at Phillips or elsewhere in the oil and petrochemical sectors. One history of OSHA inspections of Phillips facilities in the Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Arkansas region prior to the Houston explosion, showed 18 deaths and “multiple hospitalizations.” Beyond Phillips, a series of accidents, fires and explosions throughout the U.S. oil and petrochemical sectors had occurred during the 1980s and early 1990s. A number of American journalists at that time – at the Austin American-Statesman (Texas), National Journal (Washington., DC), New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, and others (see “Sources” below) – had all published in-depth stories probing the rash of fires, explosions, and other mishaps then occurring throughout the oil refining and petrochemical sectors. And in many of the reported mishaps, failure to stay on top of plant maintenance and capital repair with an experienced and sufficient workforce was cited as among the chief causes. ‘Skimping on safety,” in other words – whether driven by takeover-related financial pressures, or just plain corporate neglect and/or greed – had become a too common reality in the oil and petrochemical sectors, putting workers and nearby communities at risk.

|

“Most Hazardous” Between 1984 and 1991, a series of fires and explosions at U.S. oil refineries and related facilities killed more than 80 workers and injured more than 900. In California, injuries to oil refinery workers which resulted in at least one day of lost work, increased 32 percent between 1989 and 1990, rising from 214 to 284, according to statistics compiled by the state OSHA. “Within the petrochemical industry, petroleum refining has been identified as the most hazardous sector,” reported the U.S. OSHA and the Labor Department to then President George Bush in the wake of the Phillips explosion. “All of the data sources, including OSHA’s own inspection data, indicate that a fire or explosion is more likely in petroleum refining than in other petrochemical sectors.” The OSHA/Labor Department report to President Bush also pointed out some other worrisome trends in the petrochemical industry, namely, that: the Bureau of Labor Statistics had found “an increase in injury rates in the petrochemical industry since 1985;” the number of “serious” violations found by OSHA inspections of petrochemical facilities “has increased significantly;” increases in the size of industrial processing units, changes from multiple-batch operations to continuous-train operations, and reduced spacing of processing equipment have resulted in an increased risk of explosion and of injury or death to workers; and, inadequacies in engineering controls, supervision, employee training programs, improper tools and equipment, and fire and rescue equipment — all the result of inadequate management systems — contributed to accidents themselves and to severity of their impact. |

Phillips Again

1999-2000

Phillips Petroleum, meanwhile, would regain its economic footing after the 1989 explosion. It would reap multi-billion dollar annual revenues across its U.S. and global operations through the 1990s. But there would also be additional accidents. Nearly a decade after its 1989 explosion, Phillips had more explosions at its Pasedena, Texas chemical complex. In April 1999, a rail car containing polypropylene blew up. Another explosion and fire occurred on June 23 that year as two contractor workers were killed and three others injured. Phillips was fined $204,000 by OSHA for 13 alleged safety and health violations in the wake of the June 23rd explosion and fire. A third incident occurred in August 1999, when there was an explosion in the polypropylene section of the plant.

Then, on March 27, 2000, another explosion occurred at the Pasadena complex, this time at a chemical process tank. The tank had been out of service for cleaning but had no pressure or temperature gauges that would have provided warnings to workers. In this explosion, one worker was killed, while 71 others were injured (32 Phillips employees and 39 subcontractors), some taken to local hospitals for burns, smoke inhalation, and other injuries. The fire that followed produced huge plumes of black smoke (see NYT photo below) that spread over the Houston Ship Channel and neighboring residential areas. It took work crews five hours of digging through rubble to locate the body of the dead worker, Rodney Gott, a 45-year-old supervisor and long-time employee at the plant who had barely survived the 1989 explosion.

March 28, 2000. New York Times early reporting and photos of explosion and evacuated workers at Phillips Petroleum’s Houston chemical complex, where one worker was killed, and in later accounting, 71 others injured.

The March 2000 explosion involved a process in which a type of plastic is made with butadiene. OSHA’s regional administrator, John B. Miles Jr., reporting on that process in the K-resin unit, where the blast occurred, observed: “The primary violations were the failure to properly train workers in the hazards associated with the reaction of the butadiene chemical. We found 30 instances of that where they failed to train their operators and supervisors.” OSHA’s six-month investigation concluded that failure to train workers properly was a key factor in the explosion and fire, and proposed that Phillips be fined $2.5 million in penalties for 50 alleged safety violations. In the broader business arena, meanwhile, Phillips was about to experience some major change.

Conoco-Phillips

On August 30, 2002, Phillips merged with Conoco, another large oil company, forming ConocoPhillips, then the third largest integrated energy company and second-largest refining company in the United States. Ten years later, however, in 2012, the ConocoPhillips creation would reorganize and split into two separate companies. The new Phillips 66 company would keep the refinery, chemical, and pipeline assets formerly held in ConocoPhillips, as well as the brand name and trademark used by the original Phillips Petroleum. The other company, using the ConocoPhillips name, would include the upstream oil and gas exploration and production operations.

Graphic showing some of the business evolution of the Phillips and Conoco oil companies from the early 1900s through their 2002 merger and subsequent 2012 split into separate operating companies.

Of course, becoming larger by merger, or more focused as separate, specialized companies, did not necessarily translate into safer operations. Conoco and Phillips, together or separate, would continue to have safety problems through the 2000s and 2010s, regardless of their business structure. Among some their incidents during these years, for example, have been the following (not a complete list):

2001. Part of damage in the wake of explosion and fire at then Conoco-owned Humber Refinery in England, for which ConocoPhillips was fined & cited. |

2003. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) filed a report on the 2003 storage tank explosion & fire at the ConocoPhillips tank farm in Glenpool, OK. |

2009. Crumpled storage tank at ConocoPhillips’ Billings, MT refinery following fire. L. Mayer/Billings Gazette. |

A well head gas leak sparked a fire at ConocoPhillips well near Chetwynd, B.C. November 2008. |

Stock photo. Bayway oil refinery, Linden, NJ. |

Title card, backgrounder, ConocoPhillips WY gas plant. |

Explosion & fire at a Phillips 66 natural gas liquids line at Paradis, LA killed one worker and injured 3 others. |

The Phillips 66 Wood River oil refinery in Roxana, Illinois looking west towards the Mississippi River. |

March 15, 2019. Fire at Phillips’ Carson , CA refinery. |

U.K. Refinery Explosion

April 16, 2001. Conoco had a major explosion and fire at its Humber Refinery in North Lincolnshire, England on Easter Monday. With most workers away for the holiday, injuries were few and there were no fatalities. In nearby residential areas, however, windows and doors were blown in. And damage at the plant and some adjacent areas was extensive, as the refinery was shut down for several weeks. The incident was investigated by the U.K. Health and Safety Executive and ConocoPhillips was fined £895,000 and ordered to pay £218,854 costs. The Health and Safety Executive cited the company for failing to effectively monitor erosion in the refinery’s pipework. The company pleaded guilty to the charges and implemented a new inspection program.

Storage Tank Explosion

April 7, 2003. An 80,000-barrel storage tank at a ConocoPhillips tank farm in Glenpool, Oklahoma, exploded and burned as it was being filled with diesel. The resulting fire burned for about 21 hours and damaged two other storage tanks in the area. The cost of the accident was placed at more than $2.3 million but there were no injuries or fatalities. Some nearby residents were evacuated, and schools were closed for 2 days.

Refinery Explosion & Fire

July 23, 2003. A gasoline processing unit at ConocoPhillips’ refinery in Ponca City, Oklahoma exploded into flames, sending three workers to the hospital. One worker on the scene reported a fireball shooting as high as 100 feet into the air.

Alaska Oil Spill

2004-2007. Polar Tankers, a ConocoPhillips subsidiary, pleaded guilty to a criminal charge of covering up an oil spill off the coast of Alaska three years earlier. The company was ordered to pay a $500,000 criminal fine and $2 million to the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation.

Canada Well Fires

December 2007. An out of control well fire at a ConnocoPhillips natural gas well near Tumbler Ridge, British Columbia burned for several weeks before it was brought under control. A seconf gas well fire at another ConocoPhillips location near Chetwynd,m B.C. occured in November 2008.

Refinery Safety

In 2009 OSHA proposed fines of $92,000 for the ConocoPhillips Bayway Refinery in Linden, New Jersey (830 workers) for repeat violations that left workers “at risk of accidents that could result in injury or possible death.”

Refinery Tank Fire

December 24, 2009. A storage tank at the ConocoPhillips refinery in Billings, MT caught fire on Christmas Eve. The 97,000 bbl/ 4 million- gallon tank was about one-quarter fill with asphalt and pitch, accounting for thick dark smoke with soot during the blaze. There were some complaints from nearby residents about odors and soot. ConocoPhillips later reported emissions from the fire included 6.8 tons of sulfur dioxide, 10.4 tons of particulate matter, 5 tons of carbon monoxide, 1.5 tons of hydrocarbons and 400 pounds of nitrogen oxides.

Refinery Fire

April 29, 2010. Fire reported at Conoco Phillips’ 306,000 bbls-per-day Wood River refinery at Roxana, Illinois. Fire broke out at a sulfur treatment unit and according to the company was safely extinguished with no reported injuries or offsite impacts.

Gas Plant Burns Workers

August 22, 2012. A flash fire at the Conoco-Phillips Lost Cabin natural gas processing plant near Lysite, Wyoming burned four contract workers. Three of the workers were helicoptered to burn centers for medical attention and a fourth was sent by ambulance to Riverton Memorial Hospital. An earlier explosion and fire at this same plant on June 5, 2010, destroyed one of its units and also triggered automated calls to local residents warning them to evacuate. There were no injuries in that fire. The plant strips carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide from natural gas wells in the area.

Pipeline Explosion & Fire

February 9, 2017. A Phillips 66 natural gas liquids pipeline exploded into a raging inferno at Paradis, Louisiana, killing one worker and injuring three others. Local officials reported that residents of some 60 homes in the area were temporarily evacuated. The fire burned for three days before being extinguished. The line is near the Williams Discovery natural gas plant about 30 minutes west of New Orleans.

Hydrofluoric Acid Leak

February 11, 2017. Seven workers were sent to the hospital after a hydrofluoric acid leak at Phillips 66’s Ferndale Refinery, located in the Cherry Point area, west of Ferndale, WA. The leak was from the refinery’s alkylation unit where hydrofluoric acid is used to convert refining byproducts into octane-boosting components of gasoline. The Washington State Department of Labor & Industries fined Phillips $37,800 for the leak, calling the incident “serious” and charging that Phillips “did not implement safe work practices for the control of hazards for the employees” and did not inform the contract employer of the known potential hazards related to the work.

Lawsuits & Settlements

August 20, 2018: Phillips 66 agreed to settle alleged Clean Air Act and other violations at its Wood River Refinery in Illinois. Under the terms of the settlement filed in federal court, Phillips 66 agreed to pay a $475,000 fine (and make other payments) for leaking valves and pumps that caused excess emissions of dangerous chemicals, some occurring in 2009. A 2014 inspection reportedly revealed hydrocarbon emissions escaping from three vents and 17 roof seams at the refinery. Benzene was reportedly leaking from 14 locations on-site. Phillips agreed to make $10.8 million worth of changes at the refinery to comply with federal and state standards. In 2017, the Phillips refinery reached another settlement in a separate case in which 183 properties near the refinery claimed they were polluted by leaked underground toxic chemicals released from the refinery over decades that had migrated off site. In October 2016, the Phillips refinery reached a third settlement over allegations it had released mercury, ammonia, and other byproducts into the Mississippi River.

Refinery Fires

May 1, 2019. For the second time in less than two months, Los Angeles firefighters were called to put out a blaze involving the crude oil pumps at the Phillips 66 refinery in Carson, CA. A similar incident occurred on March 15, 2019 when three of the refinery’s four crude oil pumps were involved in a fire that took about three hours to put out.

For additional stories at this website on the history of oil refinery explosions and fires, see the following: “Texas City Disaster: BP Refinery, March 2005” (about BP’s negligence in the 2005 Texas City, TX oil refinery explosion & fire that killed 15 workers and injured another 180, including 60 Minutes TV coverage and details on related litigation); “Inferno at Whiting: Standard Oil, 1955” (story about the eight-day catastrophic oil refinery fire near Chicago in 1955, and later leaks, spills, and waste issues at the refinery under Amoco and BP management); and, “Burning Philadelphia”( a story about the 1975 Gulf Oil Co. refinery fire in that city). For another story on a petrochem plastics plant explosion and fire, see, “Shell Plant Explodes, 1994: Belpre, Ohio.”

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 30 July 2019

Last Update: 19 July 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “The Phillips Explosion – Pasadena, TX: 1989,”

PopHistoryDig.com, July 30, 2019.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Patrick J. Spain & James R. Talbot (eds), Hoover’s Handbook of American Companies, 1996, pp. 696-697.

Milt Moskowitz, Michael Katz and Robert Levering, “Phillips Petroleum,” Everybody’s Business, An Almanac: The Irreverent Guide to Corporate America, Harper & Row, 1980, pp. 522-525..

“Phillips Petroleum Company,” Encyclopedia .com / International Directory of Company Histories, Thomson Gale, 2006.

Jim Greer, “Phillips’ Ties to Hula Hoop Brings Rich History to Conoco Marriage,” Houston Business Journal, December 2, 2001.

“Phillips Disaster of 1989,” Wikipedia.org.

“T. Boone Pickens,” Wikipedia.org.

“Impact on Corporate America,” Boone Pickens.com.

Robert J. Cole, “Pickens in Bid for Phillips,” New York Times, December 5, 1984.

Associated Press, “Oil Takeover Bid Dropped,” Washington Post, December 24, 1984, p. A-3;

“Icahn Offers $8.5 Billion For Phillips Petroleum Co.,” Washington Post, February 6, 1985, p. D-11

Steven P. Rosenfeld, “Phillips Sues to Block Icahn Bid,” Washington Post, February 7, 1985, p. E-4.

Lee A. Daniels, “Phillips Seems To Be On Mend,” New York Times, April 6, 1987, p. D-1.

James R. Norman, “What The Raiders Did To Phillips Petroleum,” Business Week, March 17, 1986, pp. 102-103.

Michael Arndt, “Raiders Leave Mark on Phillips` Town,” Chicago Tribune, September 27, 1987.

Associated Press, “Plastics Plant Near Houston Explodes; 80 Injured,” Washington Post, October 24, 1989, p.

Roberto Suro, “Plastics Plant Explodes; Many Missing,” New York Times, October 24, 1989, p. A-18.

Joseph A. Kinney, “OSHA May Be Looking In The Wrong Places,” The Houston Post, Op-Ed, Sunday, October 29, 1989.

David Malakoff, “Texas Explosion Exposes Weak Safety Rules,” Not Man Apart, Friends of the Earth, Washington, DC, Dec.1989-Jan.1990, p. 4.

U.S. Fire Administration, Technical Report Series, “Phillips Petroleum Chemical Plant Explosion and Fire, Pasadena, Texas,” USFA-TR-035/ FEMA, October 1989.

Caleb Solomon, “Rash of Fires at Oil And Chemical Plants Sparks Growing Alarm,” Wall Street Journal, November 7, 1989, p. 1.

Bill Disessa, “Oct. 23, 1989: Terror from Phillips Blast Still Haunts,” Houston Chronicle, October 21, 1990.

Testimony of Robert E. Wages, V.P., Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers International Union, Before the Environment and Housing Subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations, U.S. House of Representatives, in Hearing record, “Adequacy Of OSHA Protection For Chemical Workers,” November 6, 1989, No. 24-782, 1990, Washington, D.C., pp. 79-121.

“OCAW Warning Ignored Before Houston Explosion,” AFL-CIO News, November 30, 1989.

OCAW, “Out of Control: OCAW Documents 5 Years of Death and Destruction in Oil Refineries,” New Release with attachments, OCAW, Denver, CO, January 19, 1990, p. 1.

John Gray Institute, “A Study Of Safety And Health Practices As They Pertain To The Reliance Upon Contractors In Selected Petrochemical Industries,” Lamar University, Beaumont, Texas, 1990, p. 21.

“Phillips Facing Fine For Texas Explosion,” Kentucky New Era, April 18, 1990.

Richard Leonard, “Contracting Out — A Threat To The Environment,” LRA’s Economic Notes, 1990, p. 5.

U.S, Department of Labor, Elizabeth Dole, Secretary; Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Gerard F. Scannell, Assistant Secretary, “Phillips 66 Company; Houston Chemical Complex Explosion and Fire; Implications for Safety and Health in the Petrochemical Industry: A Report to the President,” April 1990.

News Release, U.S. Department of Labor, “Dole Proposes More Than $6 Million In Penalties For Phillips 66 Pasadena, Texas, Fatal Fire/Explosions,” April 19, 1990, p. 1.

Michael Parrish, “Phillips Fined $5.7 Million for Blast at Refinery… OSHA Cites the Oil Company for 575 Safety Violations in Connection with the Explosion That Killed 23 and Injured More than 130,” Los Angles Times, April 20, 1990.

“OSHA Hits Phillips,” Corporate Crime Reporter, April 30, 1990.

Kirk Victor, “Explosions on The Job,” National Journal (Washington, DC), August 11, 1990.

Oil, Chemical & Atomic Workers Union, Video and Script #9 (May 1990), Out of Control: The Story of Corporate Recklessness in the Petrochemical Industry, Produced by the Organizing Media Project, Washington, D.C., 1990.

Fred Millar, “Too Close for Comfort,” Friends of the Earth Magazine, Winter 1991, p. 10.

Keith Schneider, “Petrochemical Disasters Raise Alarm in Industry,” New York Times, June 19, 1991, p. A-22.

“Phillips 66 to Pay Record $4 Million,” Washington Post, August 23, 1991.

Testimony of Robert E. Wages, OCAW, “OSHA’s Proposed Safety Standard For Highly Hazardous Chemicals,” Houston, TX, 1991, in New Solutions, Fall 1991, p. 94.

David E. Benson, “Potential Dangers of Oil Plants Stir Debate,” Austin American-Statesman, July 5, 1992, p. B-3.

Willy Morris, “Refinery Cutbacks Are Possible Culprit in Spate of Accidents,” West County Times (W. Contra Costa County, CA), August 24, 1992, p. 1-A.

“Petrochemical Accidents,” West County Times (Contra Costa County, CA) August 24, 1992.

Caleb Solomon and Allanna Sullivan, “Phillips Inquiry Disputes Claims Over Explosion; Some Workers Accuse Firm of Telling Them to Lie About 1989 Plant Blast,” Wall Street Journal, July 30, 1992, p. A-4.

Allanna Sullivan and Caleb Solomon, “U.S. Clears Phillips Petroleum of Trying to Mislead Inquiry Into Fatal Explosion,” Wall Street Journal, November 20, 1992, p. A-8.

Robert E. Wages, President, Oil, Chemical & Atomic Workers International Union, AFL-CIO, Letter to Jack Doyle, Friends of the Earth, Washington, DC, February 26, 1993.

Charlotte Anne Smith and Paul Hoversten, “‘Perils’ in Petroleum’s Shadow;” USA Today, May 17, 1993, p. 8-A.

Jack Doyle, Crude Awakening: The Oil Mess in America, Friends of the Earth (Washington, DC.) October 1993.

Jack Doyle, “Oil Slick: Profits Abroad and Poison At Home,” Washington Post, Sunday Outlook Section, A Look At Toxic America, July 31, 1994, p. C-3.

Jim Morris, “Union Leaders Express Fears For Plant Safety,” Houston Chronicle, November 20, 1994, p. 1-A.

Ray Tuttle, “Phillips Looks Back: Pickens Launched Takeover Bid 10 Years Ago,” Tulsa World, December 4, 1994.

“Phillips Plant Explodes; Search for Two Workers Continues After Chemical Fire; at Least 52 Injured,” CNN Money, March 27, 2000.

“Explosion At Texas Chemical Plant Injures 52,” New York Times, March 28, 2000, p. A-12.

“2000 Phillips Explosion,” Wikipedia.org.

Ruth Rendon, “Phillips Facing Fine for Fatal Plant Blast,” CNN.com/Houston Chronicle, September 22, 2000.

OSHA Proposes $2.5 Million Penalty Against Phillips Chemical Complex; Just Days after Announcing a New Plan to Improve Safety at its Houston Chemical Complex, Phillips Chemical Co. Has Been Fined $2.5 Million by OSHA,” EHS Today, September 24, 2000.

Alan S. Brown, “Phillips K-Resin Plant Explosion Kills One, Injures 71,” Chemical Online.com, March 30, 2000.

Robert Frank and Alexei Barrionuevo, “Phillips Petroleum, Conoco to Merge In Stock Deal Valued at $15.17 Billion,” Wall Street Journal, November 19, 2001.

“The Phillips 66 Explosion: The Rise of Process Safety Management in the Petrochemical Industry,” Root Cause Analysis, February 11, 2011.

Hugh Pickens, Ponca City Oklahoma, “Deaths and Injuries at Phillips Refineries and Chemical Plants,” ResearchIdeas.com.

“Public Report of the Fire and Explosion at the ConocoPhillips Humber Refinery on 16 April 2001,” Prepared by the Health and Safety Executive, U.K.

U.S. National Transportation Safety Board, “Pipeline Accident Report, Storage Tank Explosion and Fire in Glenpool, Oklahoma, April 7, 2003,” NTSB No. PAR-04/02.

Dawn Marks and Mac Bentley, “Refinery Blast, Fire Injures 3 in Ponca City; Gasoline Unit Explodes at ConocoPhillips Plant,” Oklahoman.com, July 22, 2003.

“ConocoPhillips Crude Unit Out,” The Oil Daily, July 23, 2003.

Reuters, “Conoco Unit Pleads Guilty to Hiding Alaska Spill,” Reuters.com, October 24, 2007.

“Burning B.C. Gas Well Could Take Weeks to Fix,” CTVbc.ca, November 12, 2008.

News Release, “U.S. Labor Department’s OSHA Cites ConocoPhillips for Repeat Workplace Safety and Health Hazards,” OSHA.gov, October 9, 2009.

Photo Gallery: ConocoPhillips Refinery Fire, Billings Gazette (Billings, MT), December 24, 2009.

United Steelworkers, “Refinery Events, January 4, 2010 – January 7, 2010.”

Clair Johnson, “ConocoPhillips Identifies Cause of Christmas Eve Fire,” Billings Gazette (Billings, MT), February 19, 2010.

United Steelworkers, “Phillips Disaster: Learning From History,” USW@Work, Winter 2010. p. 23.

Cristina Gallardo, “ConocoPhillips Wyoming Natgas Plant Blast Under Investigation,” Star Tribune (Casper, Wyoming), June 5, 2010.

“A Disastrous Century: Regulations And Worker Safety Since The Triangle Fire,” PoliticalCorrection.org, March 24, 2011.

Jeremy Fugleberg, “4 Burned in Lost Cabin Gas Plant Flash Fire,” Casper Star-Tribune (Casper, WY), August 22, 2012.

Mark Schleifstein, “Louisiana Refinery Accidents Decline, but Accident Emissions Rise, Louisiana Bucket Brigade reports,” NOLA.com / The Times-Picayune, December 4, 2012.

Carlie Kollath Wells, “Phillips 66 Pipeline Fire in Paradis Extinguished, Missing Worker Presumed Dead,” NOLA.com / The Times-Picayune, February 13, 2017.