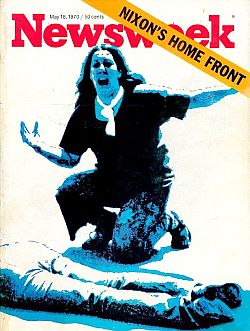

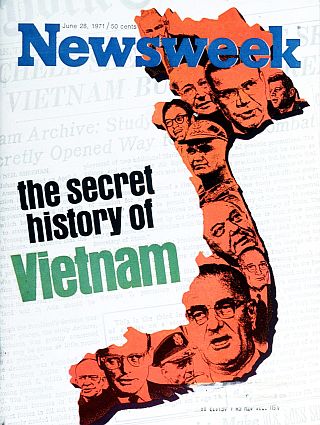

After the first newspaper stories broke on the Pentagon Papers, Newsweek and Time magazines each followed with June 28,1971 cover stories – Newsweek’s shown here with a “map”of Vietnam peopled by those making secret decisions.

Lyndon B. Johnson was then President of the United States, in his first full term following his assumption of the Presidency after JFK’s November 1963 assassination. Johnson had won the 1964 election in a landslide victory over Republican candidate, Senator Barry Goldwater.

Then U.S. Secretary of Defense, Robert S. McNamara, a JFK appointee continuing to serve in Johnson’s cabinet, and known for his statistical acumen and penchant for data-driven objectives, commissioned a top-secret study that year on the history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, going back to World War II.

McNamara – one of JFK’s brightest cabinet members and a chief architect of American strategy in Vietnam since 1961 – was having private doubts about American involvement there and wanted an “encyclopedic history of the Vietnam War” that would comprise a written record for historians and military planners in the future.

That study — though top-secret and never intended to see the light of day as a contemporary document — would prove to be explosive if revealed. It included some 46 volumes and thousands of pages of secret history – sensitive diplomatic cables, presidential decision documents, military analyses, political manipulations, and more that told the true story of what had really gone on in American-Vietnam relations over some 22 years. When it was later leaked to the press in 1971 — and after an historic First Amendment legal battle and Supreme Court ruling — this study would reveal that the American public was misled, deceived, and lied to about the real nature of U.S. involvement in Vietnam for more than two decades.

Secret Study

The top-secret study would come to be known as the “Pentagon Papers,” named for the sprawling, five-sided U.S. Defense Department headquarters just across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. in Arlington, Virginia. McNamara commissioned the study in mid-June 1967, but neither then President Lyndon Johnson nor Secretary of State Dean Rusk, knew about it.

During 1967-68 a team of some 36 researchers worked on the study coordinated at a Pentagon office adjacent to McNamara’s. Of those who worked on the study, half were high-level Pentagon staff, half security-cleared contract analysts. One of the analysts was Daniel Ellsberg, a Harvard-educated economist and one-time hawk on the war, who would later leak the study to the New York Times, Washington Post, and other newspapers. That top secret Pentagon document, and Ellsberg’s action, touched off one of the country’s fiercest battles over freedom of the press vs. government secrecy; a battle recently given dramatic form in the 2017 Steven Spielberg Hollywood film, “The Post,” starring Meryl Streep, Tom Hanks, and others. Here’s one of the trailers for that film:

Stephen Speilberg’s 2017 film, of course, focuses on the inside story at the Washington Post as it struggled with the publication decision, court battles and the Nixon Administration. Yet, the story – both before and after it got to the Washington Post and the U.S. Supreme Court – has a number of heroes and heroines, not least of whom is Daniel Ellsberg, the guy who followed his conscience and got the ball rolling. What follows below is a recounting of some of the Pentagon Papers history and why it remains important today – including a narrative chronology of events, sample newspaper headlines, legal battle, photos of some of the principals, as well as various books, television productions, and Hollywood films that came in the wake of that controversy through the present day.

Daniel Ellsberg, circa 1970s.

“Most Dangerous Man”?

In 1971, President Richard Nixon’s national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, would call him “the most dangerous man in America.” Yet, many today regard Daniel Ellsberg as a true patriot for leaking the Pentagon Papers to the press.

Ellsberg, a summa cum laude graduate of Harvard in economics in 1952, was also Woodrow Wilson Fellow at Cambridge for a year following graduation. He returned to Harvard for graduate study for a time, then joined the U.S. Marine Corps in 1954 where he served as a platoon leader and company commander, completing his service in 1957 as a first lieutenant. He later resumed graduate work at Harvard, then worked as a strategic analyst at the RAND Corporation, focusing on nuclear weapons strategy. He completed a PhD in Economics at Harvard in 1962, with an emphasis on decision theory, later becoming known for something in that field called “the Ellsberg paradox.”

By August 1964, Ellsberg was working in the Pentagon under Defense Secretary McNamara as special assistant. When Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs John McNaughton, an expert on nuclear test bans, needed an assistant, Ellsberg got the job. He then volunteered for duty in South Vietnam for two years, working for General Edward Lansdale as a member of the State Department. By 1967, he was back in the States, later that year working on the secret Pentagon study that would become the Pentagon Papers.

Vietnam, 1967: Daniel Ellsberg, right, shown with Associated Press photographer Horst Faas.

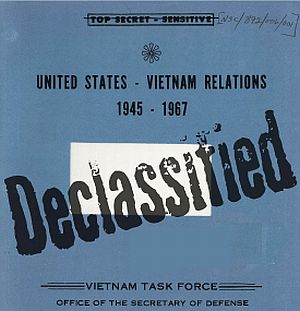

The McNamara-ordered history was completed on January 15, 1969 – just five days before the inauguration of the Nixon Administration. Officially titled: United States – Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense, it was a massive and sweeping document: 47-volumes in all, consisting of 4,000 pages of documents, 3,000 pages of analysis, and 2.5 million words — all classified as secret, top secret, or top secret-sensitive.

Among those called in to help with the project for a time was then Harvard University professor Henry Kissinger. The report offered a detailed self-examination of U.S.-Vietnamese relations and the Vietnam War. Only 15 copies were initially authorized and held in secret, made available to selected officials — two at the State Department; two for the National Archives; two copies held by the RAND Corporation (one at its D.C. office, and another at a California office); one for incoming Defense Secretary, Clark Clifford; and seven to remain at the Department of Defense.

Robert McNamara, appointed Secretary of Defense by JFK, and served LBJ until differences over the war emerged, had initiated the secret US-Vietnam history in mid-June 1967.

In November 1967, McNamara had written a memorandum to President Johnson in which he recommended that the President freeze troop levels, stop bombing North Vietnam, and turn over ground fighting to South Vietnam. McNamara by then believed the U.S. could not win the war in Vietnam. His advice to Johnson at that time was not well received and ignored.

Within a few months of his memo to LBJ — by the end of February 1968 — Robert McNamara was persona non grata in the Johnson Administration. He would resign as Secretary of Defense and move on to head up the World Bank.

Tumultuous Times

The social and political milieu in the U.S. as the secret Vietnam study was being compiled was anything but calm. During 1968 in particular, an election year, there came a series of especially volatile events that sent successive shock waves through the nation. “All hell broke loose” is how some described what would become one of the most tumultuous periods of American history – between January 1968 and November 1968.First came the Tet Offensive in Vietnam in late January 1968 (“Tet” marking the lunar new year holiday), when North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces launched a coordinated attack in South Vietnam that undermined what President Johnson and the U.S. military were saying about the war. At home, Johnson’s well-intentioned Great Society domestic agenda for helping the poor was being circumscribed by the war. Then on February 27th, respected CBS-TV newsman, Walter Cronkite, who had gone to Vietnam after the Tet Offensive, offered an on-air commentary during the regular CBS Evening News program watched by millions, concluding that the Vietnam War was “mired in stalemate.” That broadcast is regarded as seminal in raising doubts among mainstream Americans about U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Johnson, meanwhile, was being challenged for his party’s presidential nomination. On March 12, 1968, anti-war candidate, Senator Eugene McCarthy staged a surprised challenge to Johnson in the New Hampshire primary. Four days later, Senator Robert F. Kennedy announced he would also seek the Democratic Presidential nomination.

Walter Cronkite's February 1968 "stalemate-in-Vietnam" TV commentary was devastating to LBJ.

Nixon-Agnew button.

Early 1970s: Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo, who made late night copies of the Pentagon Papers while at RAND.

Ellsberg’s Move

Meanwhile, by January 1968, Daniel Ellsberg had spent about 8 months working on the McNamara-ordered Vietnam history, and he regarded the Tet Offensive a troubling development, among others. Still, he continued to work as a government contractor, Vietnam trouble-shooter, and policy advisor, meeting with government officials, presidential candidates – and even in early 1969 — meeting with Henry Kissinger, President Richard Nixon’s national security advisor. Kissinger asked Ellsberg to prepare a list of policy options for the new Nixon administration, which Kissinger did not include in those submitted to Nixon.

Some months later, however, by October 1, 1969, Ellsberg began to cross the line from government contractor and Vietnam analyst to anti-war activist and government whistleblower. As a RAND analyst, he had access to an authorized copy of the 47 volume Pentagon Papers – and he had also read the entire study. Over a three-month period beginning that October, Ellsberg and a RAND colleague named Anthony Russo, began photo-copying the study bit by bit late at night, returning it to the RAND safe each morning. But once copied, Ellsberg would not immediately distribute the sensitive materials to the press.

Ellsberg also tried other avenues to advance his concerns about the Vietnam War. On October 12, 1969, he and several RAND colleagues wrote a letter to the Washington Post opposing the Nixon Administration’s Vietnam policies and statements. As for the secret document he was copying, his first thought was to distribute a few copies to selected U.S. Senators. Members of the U.S. Senate (or the U.S. House of Representatives) could release sensitive papers on the Senate or House floor and face no repercussions, as they could not be prosecuted for anything they said in official proceedings.

Among those receiving early copies of the Pentagon Papers from Ellsberg was Sen. J. William Fulbright (D-AR) a critic of the Vietnam War and a careful foreign policy thinker.

In 1966, he held some of the first public hearings on the Vietnam War and would publish The Arrogance of Power that year as well, a book sharply critical of the war, in which he attacked its justification and Congress’s failure to set limits on it. As for the Pentagon, in 1970 he would publish The Pentagon Propaganda Machine, a short book focusing on the military’s public relations campaigns.

Fulbright, however, would not release the secret Pentagon study Daniel Ellsberg brought to him. Instead, he decided to request a copy of the full secret Vietnam history from Secretary of Defense, Melvin Laird. On December 20, 1969, Laird replied but refused to release the Pentagon study to Fulbright.

War Protests

Protest over the Vietnam War, meanwhile, had grown. Two large marches on Washington – with hundreds of thousands of protesters — occurred in October and November of 1969. In early November 1969, Nixon made his “silent majority” speech, claiming that most Americans supported his policies to end the war.

Then on April 30th, 1970 it was revealed that the U.S. had invaded Cambodia in an effort to stop North Vietnamese using that neighboring country to raid South Vietnam. The Nixon Cambodia incursion is seen as a broadening of the war, and it sets off student demonstrations around the U.S., including one at Kent State University in Ohio on May 4th, where national guard troops are called out to quell the protests. Four Kent Sate students are killed by guardsman on the campus during the demonstrations, setting off further protests across the nation.Ellsberg, meanwhile, has left RAND and becomes a senior research associate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for International Studies, where he meets others, including William Bundy, a former Vietnam war architect, and two professors, Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn, with whom he shares the Pentagon Papers. Back in Washington, Ellsberg continued to distribute portions of the Papers to selected Senators and Congressmen, including Sen. George McGovern (D-SD), a leading opponent of the war, and Republican Rep. Pete McCloskey (R-CA). But both choose not to act on the secret document.

On May 13, 1970, Ellsberg testifies before Senator Fullbright’s Senate Foreign Relations Committee, but does not disclose the secret Pentagon study he holds. Several months later, in September that year, Ellsberg publishes an essay, “Escalating in a Quagmire,” presented at a conference of the Political Science Association. He also meets with Secretary Kissinger around this time to discuss his concerns. Kissinger offers him a position as an advisor, which Ellsberg declines. Ellsberg would later confront Kissinger again, publicly, over Vietnam casualty reports, at a January 1971 MIT conference.

Going To The Press

In early March 1971, Ellsberg meets with New York Times reporter, Neil Sheehan. Sheehan had covered the Pentagon and White House for the Times since the mid- and late- 1960s, writing on political, diplomatic and military issues. He was also a former UPI correspondent whom Ellsberg had met in Vietnam. By 1971 Sheehan worked in the Washington bureau of the Times. At his first meeting with Sheehan, Ellsberg only describes the document he has, and wants to be sure that the Times will publish it. He and Sheehan would meet again later.

Tom Oliphant of the Boston Globe

The Boston Globe story is the first public reporting that a secret U.S./Vietnam history even exists (except for a brief mention in the Oct 25, 1970, issue of Parade magazine). Although Oliphant and the Globe are the first to write publicly about the Papers, no other media picked up on it. Oliphant had interviewed Ellsberg earlier, when Ellsberg acknowledged the study existed. Still, the Globe at this point did not have access to the secret study’s content. Ellsberg and his wife, meanwhile, feared the government might come knocking on their door, so they begin salting away additional copies of the study with friends.

Neil Sheehan of the New York Times had covered the Pentagon and the White House in his reporting.

By April 5, 1971 Sheehan and New York Times editor Gerald Gold have set up shop in DC’s Jefferson Hilton hotel to begin reviewing the documents. The Times’ winnowing operation on the papers – called Project X – is later moved to a hotel near Times Square. (The Times’ editors and writers had holed up in hotels away from their D.C. and New York offices for fear of FBI raids).

By this time, Sheehan is joined by a broader team of reporters and editors from the Times – Hedrick Smith, Ned Kenworthy, Fox Butterfield and others. During a three-month period, up through early June 1971, while the Times prepared and selected stories to publish from the secret Pentagon study, there was much internal debate over whether and how to publish, with outside counsel recommending not publishing. Among those arguing strongly to run the secret material was senior Times editor, James Reston, who would write an early column titled, “The McNamara Papers.” Finally, on June 11th, 1971, after having the documents for nearly three months, New York Times publisher, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger gave to final approval to publish the secret material.

June 13, 1971: The New York Times publishes its first Pentagon Papers stories (shared with coverage of Tricia Nixon’s White House wedding) – “Vietnam Archive...” by Neil Sheehan , and “Vast Review of War Took A Year,” by Hedrick Smith. A box in the first story directed readers to further pages of “documentary material from the Pentagon study.”

In its Sunday edition of June 13th, 1971 (above), the New York Times published its first Pentagon Papers story on the front page in a story by Neil Sheehan headlined as the “Vietnam Archive.” That headline introduced the secret Pentagon study to Times readers, noting it covered “3 Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement” in Vietnam. There was also coverage of the August 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident, which proved to be a fictitious provocation (of a U.S. vessel fired upon at sea) that the U.S. would use to justify greater U.S. participation in the war via the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution passed by the House and Senate, and used by LBJ as a broad executive power to prosecute a major war. The first New York Times stories, their headlines, and others later, were purposely drawn to be as bland as possible, and not sensationalized, so as to show intent of publisher responsibility, as the Times was then anticipating legal challenges ahead. Still, there was much more in the Times that first day than just these two stories. In fact, that Sunday edition came in at a whopping 486 pages – much of it in supporting verbatim materials from the secret Pentagon study.

On June 14th, 1971, the Times published its second story (below) on the Pentagon Papers – it focused on the February 1965 decision to bomb North Vietnam. This story revealed that President Johnson was planning the bombing on the day he was elected to his second term, despite campaign promises he would not escalate military action. The article also described the decision process that led to the bombing campaign.

June 14, 1971. Cropped front page of the New York times featuring the second in a series of stories on the Pentagon’s secret Vietnam history. This story revealed that planning was underway to bomb North Vietnam before the U.S. 1964 Presidential election, when as a candidate, President Johnson had said he would not escalate the war.

With the Times’ second story on the sensitive Vietnam history, the Nixon Administration becomes involved in an effort to stop further publication. However, President Nixon had not known of the secret Pentagon study before the Times had run its first stories. Kissinger knew of it, but hadn’t read it. And the secret Vietnam history only covered events up to 1967, and nothing during the Nixon years — with the previous Democratic Administrations of Johnson and Kennedy being skewered initially.

On June 13th, 1971, when the first of the New York Times stories appeared, Nixon did not, at first, want to go after the Times for publishing the material. In fact, he hadn’t read the stories that morning – the day after his daughter had been married at the White House. When he did read them, and after he heard early reaction from his staff and some Cabinet members, Nixon became more concerned with going after who ever leaked the material than he was with the Times’ publication.

President Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger, early 1970s.

But Henry Kissinger and others soon convinced Nixon there was plenty to worry about. For if documents as sensitive as these could be photocopied and handed out to the press at will, how could their own Administration carry on the business of national security? They had already had some leaks of their own sensitive material, and the move to publish these Pentagon documents could only embolden others. Indeed, Nixon’s team had their own secrets about how they were conducting the war in Vietnam, Cambodia and elsewhere. There was also the anti-war movement at home that was growing beyond the campuses. In Congress, there were a dozen or so bills calling for an end to the war. Nor did Nixon care much for the press, referring to the Times and other press as “enemies.” So the Nixon Administration — driven by Nixon’s own paranoia about conspiracy efforts out to get him — soon became preoccupied with stopping publication and prosecuting those who leaked sensitive material.

Nixon’s Attorney General, John Mitchell, sent a telegram to New York Times publisher Sulzberger threatening Espionage Act prosecution if the Times does not stop publication. Mitchell cited “irreparable injury to the United States.” Violating the Espionage Act meant prison time for those convicted. The Times girded for a legal fight. They added Yale Law Professor Alex Bickel and First Amendment litigator Floyd Abrams to their legal team. Still, they continued publication.

June 15, 1971: New York Times third installment of its series on the secret Vietnam study runs with a front page story on how the Johnson Administration began U.S. ground combat operations in Vietnam. There is also the featured top headline story on the Nixon Administration’s efforts to shut down the Times’ publication of the study.

On June 15th, 1971, the third installment of the series on the secret Pentagon study is published by the New York Times – this time with a double headline. The first told of the current fight with the Nixon Administration over publication: “Mitchell Seeks to Halt Series on Vietnam But Times Refuses.” On the Vietnam history story, the headline read: “Vietnam Archive: Study Tells How Johnson Secretly Opened Way To Ground Combat.” That story described the decision to commit U.S. ground troops to Vietnam, which was first made on April 1, 1965, beginning with 3,500 Marines, then 18,000-20,000 ground troops, and escalating to 200,000 more requested by General Westmoreland in June of that year (over Ambassador Maxwell Taylor’s objections) which LBJ approved on July 17, 1965.

In this same June 15th edition, the Times wrote that court action over the Vietnam series was likely. In fact, an injunction came later that day, with Nixon’s team filing its action in federal district court in Manhattan. The presiding judge was Nixon appointee, Murray Gurfein, then hearing his first case. Judge Gurfein issued a temporary restraining order barring the Times’ further publication. Back in Washington, the Department of Justice announced that it was considering criminal penalties for the leak and publication. Also at that time, Secretary of State William Rogers, in a press conference, singled out the disclosure of the secret study for harming U.S. relations with its allies.

June 16, 1971. The New York Times reports on the Nixon Administration’s action to halt the Times’ publication on the secret Pentagon study, while also reporting another story from that study and another on related issues.

On the following day, June 16, 1971, the Times runs the dominant front-page headline announcing the government’s action against the paper: “Judge, at Request of U.S., Halts Times Vietnam Series Four Days Pending Injunction.” But the paper also runs another piece from the secret Vietnam archive, as well as a related story on Secretary of State Rogers’ concerns, and another on Senator Mike Mansfield’s (D-MT) call for Senate hearings into the history of the Vietnam War. With the Times being shut down on the story, Daniel Ellsberg then offers the Pentagon Papers to the three television networks (in those days there were only three). But each of the TV networks declines, citing FCC license vulnerability. By this time, Ellsberg and his wife Patricia go underground after Ellsberg is identified as the probable source for leaking the secret Pentagon study.

Post Joins Fray

With the New York Times now legally sidelined, the Washington Post, which had only published wire stories and summations of what the Times had been reporting about the secret study, then began its own effort to pursue the story. Ben Bagdikian, an assistant managing editor at the Post, knew Ellsberg from a time when both had been together at RAND. He had also pieced together that Ellsberg was the likely leaker, and contacted him on behalf of the Post to arrange for a copy of the study. Bagdikian flew to Boston on June 17th, 1971, met with Ellsberg to get the Papers, then flew home to D.C. in an airplane scene now made famous by the 2017 film, “The Post,” with Bagdikian and his big box of papers “belted in” on an adjacent airplane seat (photo below). He was actually carrying two copies, one for a member of Congress (Senator Mike Gravel), later to be incorporated into a formal committee record (see sidebar later below).

Scene from 2017-18 film, “The Post,” showing Ben Bagdikian of The Washington Post (played by Bob Odenkirk ), flying back to Washington after obtaining copies of the 7,000-page “Pentagon Papers” from Daniel Ellsberg in Boston. “Must be precious cargo,” observes flight attendant of his seat companion; “only government secrets” he assures her. Click for 'The Post' DVD.

When Bagdikian arrived in Washington that evening, on June 17th, 1971, he went straight to the home of Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee, where a gathered team of reporters and editors were awaiting the secret study to write stories for the following day’s edition. They soon dug into the work as the Post’s lawyers and editors debated the risks of publishing. The Post’s owner and publisher, Katharine Graham, would later approve the publication of the secret material over the telephone during a party being held at her home. Graham’s approval came despite strong objections by the Post’s legal counsel and her own worry about risking the family business. Back in New York, the Times, complying with a court order, released a list of the secret documents it held to the government, but not the documents themselves. The court rejected the government’s request for the copies. Meanwhile, the next day, the Washington Post published its first stories on the secret Pentagon study.

June 18, 1971. The Washington Post runs its first front-page stories on the secret Pentagon study: one from the study during the Eisenhower era in 1954 when the U.S. figured into a delay in South Vietnamese elections; another on how members of Congress were then mostly supporting the earlier New York Times’ publication of the secret study; a third on the Times’ actions regarding the government’s legal requests for documents; and a fourth, in the lower right hand corner, about the government’s pursuit of then suspected leaker, Daniel Ellsberg.

In its debut on the secret Pentagon study (above), the Post featured four related stories on its front page: one from the study during the Eisenhower era in 1954 when the U.S. figured into a delay of South Vietnamese elections; another on how members of Congress were then mostly supporting the New York Times’ publication of the secret study; a third on the Times’ actions regarding the government’s legal requests for the Pentagon documents; and a fourth about the government’s pursuit of then suspected leaker, Daniel Ellsberg. Upon publication, the Nixon Administration immediately goes after the Washington Post.

Assistant U.S. Attorney General, William Rehnquist, calls Post editor Ben Bradlee to inform him that further publication will be a violation of espionage laws. He also requests the Post turn over its documents. Bradlee refuses on both counts.

Some hours later – now June 19th, 1971 at 1:20 a.m – the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals temporarily enjoins the Post from further publication. Two days later, on June 21, 1971, in Federal District court in Washington, Judge Gesell denies the government’s request for a preliminary injunction against the Post, but the government immediately appeals to the D.C. Circuit.

June 21, 1971. Katharine Graham and Ben Bradlee of the Washington Post,, emerging from Federal District Court in Washington, DC after court temporarily ruled in their favor.

By this time, more than 10 other newspapers across the country had received the sensitive Pentagon study and begin publishing their own articles.

At stake in the case as it came before the Supreme Court – New York Times v. United States – is the question of whether the First Amendment allows “prior restraint” (in the form of a legal injunction/prohibition) on the publication of the Pentagon Papers (and by extension, all other information of this kind going forward) by the Times and Post, and generally, the press. It is a fundamental First Amendment challenge.

Meanwhile, as the legal questions were being sorted out in this epic case, Ellsberg was moving from motel to motel to avoid capture by the FBI, still distributing the secret Pentagon study selectively to other newspapers. On June 22nd, 1971, for example, after being contacted earlier by Boston Globe reporter Thomas Oliphant, and with the Globe agreeing to publish the secret material, Ellsberg supplies portions of the study and the Globe runs three related front-page stories; two reporting, respectively, on the JFK and LBJ roles in the secret Vietnam history, and a third reporting that Ellsberg would soon be making a statement on his role. The Justice Department then stopped the Globe from further publication with an injunction and also ordered the Globe’s documents to be impounded. Instead, the Globe’s editor, Thomas Winship, moved the documents off premises to a locker at Boston’s Logan Airport.

June 22, 1971: Boston Globe reports on JFK and LBJ roles in secret Vietnam history – and also Ellsberg. |

June 24,1971: San Francisco Chronicle reports on secret Pentagon Vietnam history, Ellsberg, & newspaper bans. |

Ellsberg would continue distributing portions of the secret Pentagon study to other newspapers, a few of which the government also tried to enjoin. The St Louis Post-Dispatch, Christian Science Monitor, San Francisco Chronicle, and Chicago Tribune were among newspapers that published material from the secret Pentagon report. By June 23rd, 1971, Ellsberg himself was interviewed on Walter Cronkite’s CBS-TV news show, when he told the anchorman that Americans were to blame for the war and “now bear the major responsibility, as I read this history, for every death in combat in Indochina in the last 25 years.”

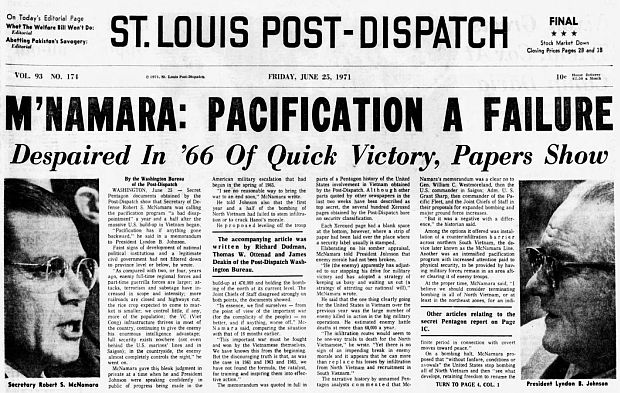

June 25, 1971: St. Louis Post-Dispatch publishes revealing front-page story from the secret Pentagon Vietnam history, running the headlines: ‘M’Namara: Pacification A Failure; Despaired In ‘66 Of Quick Victory, Papers Show,” with front-page photos of Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and President Lyndon Johnson.

On June 25th, 1971, the St. Louis Post Dispatch published a front-page story (above) on the secret Pentagon study that headlined the fact that U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara had declared the “pacification” effort in Vietnam a failure, and in 1966 he warned President Johnson there would be no quick victory. This story was a clear indication that more than just the New York Times and Washington Post were involved, as nearly an additional dozen or so newspapers – some in the heartland of the country such as the St Louis Post-Dispatch – were also publishing revealing accounts from the secret Pentagon Vietnam history.

In Los Angeles, meanwhile, a federal grand jury was convened to hear charges on the criminal aspect of the Pentagon study leak. On June 26th, 1971, a warrant was issued for the arrest of Daniel Ellsberg; his attorneys announced he would surrender the following Monday. Also on June 26th, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch came under a restraining order for its publication.

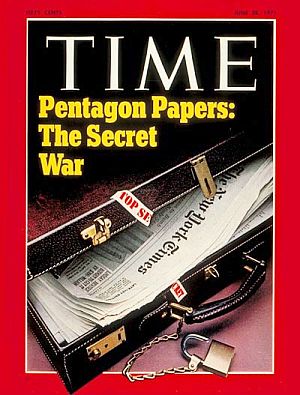

June 28, 1971: Time cover, “Pentagon Papers: The Secret War.”

…Each step seems to have been taken almost in desperation because the preceding step had failed to check the crumbling of the South Vietnamese government and its troops—and despite frequently expressed doubts that the next move would be much more effective. Yet the bureaucracy, the Pentagon papers indicate, always demanded new options; each option was to apply more force. Each tightening of the screw created a position that must be defended; once committed, the military pressure must be maintained. A pause, it was argued, would reveal lack of resolve, embolden the Communists and further demoralize the South Vietnamese. Almost no one said: “Wait—where are we going? Should we turn back?”

Also on June 28th, 1971, Daniel Ellsberg surrendered to the U.S. Attorney in Boston. There he was charged under the Espionage Act with theft and unauthorized possession of classified documents and released on $500,000 bail. Ellsberg faced a maximum sentence of 20 years in prison. Meanwhile, the New York Times/Washington Post case over the right to publish was still pending before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Late June 1971: Daniel Ellsberg appears before microphones, surrounded by reporters at the Federal Building in Boston, where he would surrender to Federal authorities after admitting he supplied the New York Times with the secret Pentagon papers.

On the following day, June 29, 1971, U.S. Senator Mike Gravel (D-AK) then attempted to read the Pentagon Papers into the Senate record as part of his filibuster on the military draft, but he was stopped by a parliamentary maneuver. He then convened a hearing of his Senate Public Buildings and Grounds Subcommittee in the middle of the night and began reading the Pentagon Papers into the hearing record, continuing to do so for three hours, and later submitting the unread remainder into the formal hearing record. (more on Gravel and these papers in later sidebar).

Then on June 30, 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court announced its decision in New York Times v. United States, with the nine justices voting 6-3, upholding the Times’ and Post’s right to publish, and declaring that all news organizations could publish any excerpt of the report they deemed newsworthy. The landmark decision made front-page news all across the country, and no more happily than at the New York Times and Washington Post – with each of those newspapers, and others, resuming their reporting on the once secret U.S.-Vietnam history.

July 1, 1971: In addition to its front page coverage of the Supreme Court’s decision, the Times continued its series on the Pentagon Papers with two of the stories appearing on the front page – one on JFK decisions – “...Made ‘Gamble’ Into a ‘Broad Commitment’,” – and another on the overthrow of South Vietnam’s President Diem.

July 1, 1971. Washington Post front page following U.S. Supreme Court decision upholding the right of the press to publish secret Pentagon Papers. Photo shows Post owner Katharine Graham, editor, Ben Bradlee, and Post reporters in Post’s newsroom receiving and celebrating the court’s decision.

The case marked the first time in modern American history that the U.S. government had actually restrained the press from publication in the name of national security, as the New York Times had been restrained for 14 days from publishing. But the Supreme Court’s decision re-affirmed the right and duty of the press to keep a watchful eye on government. Justice Hugo Black wrote, for example: “In the First Amendment the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy. The press was to serve the governed, not the governors.” Justice Black and Justice William O. Douglas added that no restraints of any sort are permissible under the First Amendment. (For a legal analysis of the importance of New York Times v. the United States, see C-SPAN’s “Landmark Cases” series on this case).

However, the controversy over the publication of the Pentagon Papers did not end with the Supreme Court’s decision upholding the right to publish. The story continued with the arrests and trial of Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo. In fact, on the day of the Supreme Court’s decision in the Pentagon Papers case, June 30, 1971 the U.S. Attorney in Los Angeles indicted Ellsberg on two counts of theft and espionage. And in some ways, this is where “the plot thickens,” as they say, for the Nixon Administration, as would be later revealed, was hot on the trail of Daniel Ellsberg.

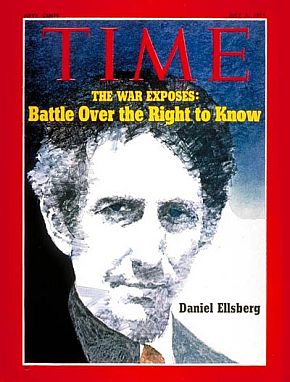

July 5, 1971: Time puts Daniel Ellsberg on it cover with story on the “Battle Over the Right to Know.” |

July 12, 1971: “Victory for The Press,” Newsweek cover story on Supreme Court ruling. |

The Ellsberg/Russo prosecution and trial would run nearly two years, from June 1971 through May 1973, and would take several twists and turns. In August 1971, Anthony Russo was called to testify before the grand jury in Los Angeles, but refused, citing his Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination. And after he was offered immunity from prosecution, he still refused to testify and was cited for contempt and put in jail. In late December 1971, a second indictment was brought against Ellsberg and Russo that superseded the original, this one containing fifteen counts. By July 29, 1972, with the trial underway, it was learned the government had wiretapped a conversation between one of the defendants and his lawyer or consultants. However, the judge in the trial, Judge Matthew Byrne, refused to stop the trial because of the wiretap. But Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas ordered a stay since an appeal has been filed at the Supreme Court. But the Supreme Court, on November 13, 1972, refuses to hear defense arguments arising from the government’s wiretap. Then on December 12, 1972, Judge Byrne, declares a mistrial in the Ellsberg-Russo case and calls for a new jury to be empaneled. On January 17, 1973, opening statements are delivered in the new Ellsberg/Russo trial. But not long thereafter, some other revelations come to light.

Charles Colson, Nixon aide. |

John Erlichman, Nixon aide. |

Howard Hunt, "plumber". |

Gordon Liddy, "plumber". |

Nixon’s Plumbers

Two years earlier in the White House, during the New York Times’ publication of the Pentagon Papers, concern about leaks and conspiracies had escalated, as Nixon and his aides fumed over the Pentagon Papers disclosures and Daniel Ellsberg.

During June and July 1971 several of Nixon’s top aides and chief advisors — through a series of memos, telephone calls, and meetings — were involved in a continuing harangue about the leaks, Ellsberg, and what they were going to do about it. All of this led to an internal, self-reinforcing revving up of the group, including Nixon, to stop leaks and take revenge, initially on Ellsberg, the first among a variety of “enemies.”

Henry Kissinger, for example, Nixon’s National Security Advisor – who had once praised Ellsberg and sought his expertise – painted a very dark and damaging portrait of Ellsberg on the evening of June 17, 1971 in the Oval Office with Nixon, John Ehrlichman, and Bob Haldeman present.

Another top Nixon aide, Charles Colson, in a July 1st, 1971 telephone call with retired CIA agent named E. Howard Hunt, helped inspire and recruit Hunt to see what he could come up with on Ellsberg and other projects, suggesting, among other things, that Ellsberg might be “tried in the newspapers.” By July 6, 1971 Hunt was hired as White House consultant.

Meanwhile, the FBI and CIA by this time had been looking into Ellsberg’s past at the request of the White House with some urgency. But this was apparently not sufficient, as a special and covert White House Special Investigations Unit – later to be known as the “plumbers” – had been created on July 24, 1971 to help stop the leaking of classified information. Two junior aides were appointed to administer the unit – Egil “Bud” Krogh, Jr., and Kissinger aide David Young, Jr. This unit would come under the supervision of Nixon’s Domestic Advisor, John Ehrlichman.

On July 28, 1971, Howard Hunt sent a memo to Colson entitled “Neutralization of Ellsberg” with an outline of several proposed actions. “Building up a file on Ellsberg,” Hunt wrote, was “essential in determining how to destroy his public image and credibility.” One of the proposals from Hunt was to burglarize the offices of Ellsberg’s one-time psychiatrist in Los Angeles,…Hunt’s plan to burglarize the office of psychiatrist Dr. Lewis Fielding sought a “mother lode” of infor-mation about Ellsberg’s mental state in order to discredit him. Dr. Lewis Fielding, to obtain a “mother lode” of information about Ellsberg’s mental state in order to discredit him. In August 1971, that plan is fleshed out in more detail at the Old Executive Office Building near the White House and is later approved by Ehrlichman under the condition that it “is not traceable.” On September 3, 1971, the burglary of Fielding’s Beverly Hills Los Angeles office was carried out by “plumbers” Hunt, Liddy, Eugenio Martínez, Felipe de Diego, and Bernard Barker (the latter three, former CIA). In Fielding’s burgled office and crow-barred filing cabinet, Nixon’s plumbers found Ellsberg’s file, but it apparently did not contain the embarrassing information they had hoped for and left it discarded on the floor. Hunt and Liddy then planned to break into Fielding’s home, but Ehrlichman did not approve the second burglary. (This plumbers unit, meanwhile, would be the one and the same group made famous in the 1972 burglary of Democratic Campaign headquarters at the Watergate office complex in Washington DC — the break in and subsequent cover-up that would lead to the Watergate scandal and the resignation of President Richard Nixon).

Back at The Trial…

Back at the Ellsberg/Russo trial on April 26, 1973, a memo to Judge Bryne revealed the White House “plumbers” break-in of Dr. Fielding’s office seeking Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatric records. And there was more. On May 9th, further evidence of illegal wiretapping of Ellsberg was revealed, as the FBI had recorded numerous conversations between he and Morton Halperin without a court order. In addition, it was also revealed that during the trial, Judge Byrne – the residing judge in the trial – had personally met with Richard Nixon’s domestic advisor, John Ehrlichman, who had offered Byrne a position at the FBI. Given the gross governmental misconduct and illegal evidence gathering, Judge Byrne dismissed all charges against Ellsberg and Russo on May 11, 1973. The dismissal was front-page news.

May 12, 1973. New York Times headlines proclaiming government charges against Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo in their Pentagon Papers trial are dismissed and the are free, with the judge noting “improper government conduct” in that trial.

At the White House, however, President Nixon was not happy with the outcome of the Ellsberg trial, nor with the fact that earlier, on May 2, 1972, the New York Times had been awarded a Pulitzer Prize for “meritorious public service in journalism” for its reporting on the Pentagon Papers. While speaking to Alexander Haig and Bob Haldeman at the White House on the day the mistrial is declared, Nixon says: “…Son-of-a-bitchin’ thief is made a national hero and is gonna get off on a mistrial. The New York Times gets a Pulitzer Prize for stealing documents. They’re trying to get at us with thieves. What in the name of God have we come to?”

Fifteen months later, on August 8th, 1974, Richard M. Nixon announced in a televised address that he would resign as President of the United States the following day to escape what would have been most certain impeachment by the House and removal by the Senate for the crimes of the Watergate Scandal, which began, in part, with the White House paranoia over the publication of the secret Pentagon Papers (see also at this website “The Frost-Nixon Biz,” which covers the 1977 David Frost TV interviews with Richard Nixon about the “plumbers” and Watergate, and the books, stage play, and film that followed).

Books & Film

Popular History

In the years following the publication of the Pentagon Papers and the Daniel Ellsberg disclosures, there came a number of books and films on the controversy, its various characters, and related Vietnam War histories and politics. Among the first of these was a July 1971 Bantam Books paperback of some 677 pages that compiled what the New York Times had published in its newspaper series. The cover of that book appears below left, which also provided attribution on the cover for the various Times reporters involved, adding — “with key documents and 64 pages of photographs.”

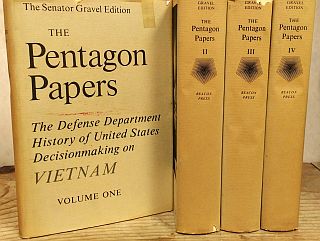

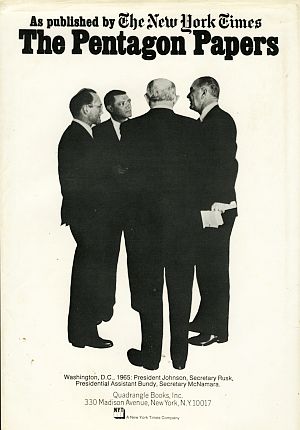

Also in 1971, the New York Times-owned company, Quadrangle Books, published a hardback volume of some 810 pages (above right) billed at the “definitive edition” of the Pentagon Papers as published by the Times, plus supplementary materials. It was offered as a comprehensive volume for libraries, universities, and private citizens. It included the ten chapters covered by the Times in its June and July 1971 stories, plus the full texts of the government documents that appeared in those stories; the court proceedings in the case of The New York Times Company vs. The United States; pictorial documentation of the Pentagon study in 60 pages of photographs; a glossary of names, code words, abbreviations and technical terms used in the Pentagon study; expanded and illustrated biographies of American and Vietnamese officials prominent in the study; and a 32-page index. Then there was also “the Gravel edition” of the Pentagon Papers, with a little history of its own.

|

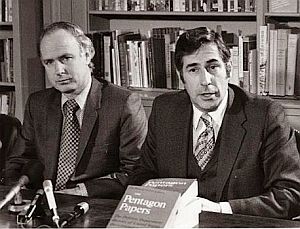

“The Gravel Edition”  Senator Mike Gravel, early 1970s. On the evening of June 29, 1971, after being thwarted in his attempt to read the secret study on the floor of the U.S. Senate, Gravel resorted to using his Buildings and Grounds Subcommittee as a way to enter the Pentagon Papers into the formal Congressional record. As he began reading from the papers with the press in attendance, Gravel noted: “It is my constitutional obligation to protect the security of the people by fostering the free flow of information absolutely essential to their democratic decision-making.” He read until 1 a.m., though finally inserting some 4,100 pages of the Papers into the record of his subcommittee. The following day, the Supreme Court, in New York Times Co. v. United States, ruled in favor of the newspapers’ right to publish the Pentagon Papers, which then continued at the Times, Post, and other newspapers. In addition, by July 1971, Bantam Books published an inexpensive paperback edition of the papers containing the material the New York Times had published.  "The Senator Gravel Edition" of the Pentagon Papers, published by Beacon Press, October 1971. Not shown, Chomsky/Zinn Vol. 5.  UUA President Bob West and Senator Mike Gravel respond to the FBI’s attempt to seize UUA bank records in 1971. Senator Gravel’s involvement with the Pentagon Papers, meanwhile, had made him into something of a national political figure at that time. He became a sought-after speaker on the college lecture circuit and was also sought out for political fundraisers. The Democratic candidates for the 1972 presidential election sought his endorsement, and he later backed Maine Senator Ed Muskie. Gravel continued fighting the Nixon Administration on Vietnam. In April 1972, he appeared on all three nightly TV newscasts criticizing Nixon’s “Vietnamization” plan for the South Vietnamese to shoulder the war fighting, while also making other secret government war documents public. |

Sanford J. Ungar first published this book with E.P, Dutton; shown here in Columbia Univ. Press edition. Click for copy.

Ungar had also written on the Pentagon Papers and Ellsberg in 1971-72 for the Washington Post, publishing one story there titled, “Daniel Ellsberg: The Difficulties of Disclosure,” in a Sunday edition, April 30,1972, tracking the difficulties Ellsberg encountered trying to put the secret Pentagon materials on the public record.

Ellsberg himself published his own quick book on the Pentagon Papers in July 1972 titled simply, Papers On The War (Simon & Schuster, 309pp). In 2002, Ellsberg would publish a second account on the Pentagon Papers case, Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers, which reached bestseller lists across the nation and won several awards, including the American Book Award.

One book profiling Ellsberg’s history with the Pentagon Papers is Steve Sheinkin’s Most Dangerous: Daniel Ellsberg and the Secret History of the Vietnam War, published by Roaring Brook Press in 2015 and was a National Book Award finalist.

Other popular and academic volumes on the Pentagon Papers, some from the perspective of journalism, and others probing the trail of litigation or parsing the Supreme Court’s decision, would also come into print over the next 40 years – not to mention numerous periodical and law review articles (click on any book cover below to go to Amazon page for that book).

Among books exploring the publishing and/or legal aspects of the Pentagon Papers, for example, is David Rudenstine’s 1996 work, The Day the Presses Stopped: A History of the Pentagon Papers Case (University of California Press).

In 2013, James Goodale, the former general counsel and vice chairman of the New York Times, published Fighting for the Press: The Inside Story of the Pentagon Papers and Other Battles, which includes his account representing the Times before the Supreme Court in the Pentagon Papers case.

There are also two books from the Washington Post’s Ben Bradlee and Katharine Graham, which include sections on the Pentagon Papers: Graham’s Personal History of 1997, published by Alfred A. Knopf, and Bradlee’s A Good Life: Newspapering and Other Adventures, published by Simon & Schuster in 1995. Presidential biographies – especially those on Johnson and Nixon – also have history related to the Pentagon Papers and Vietnam era decision making.

Complimenting the early books on the Pentagon Papers is David Halberstam’s well-received 1972 best seller on Vietnam, The Best and The Brightest. Halberstam’s book offers details on how the decisions were made in the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations that led to the war, focusing on a period from 1960 to 1965, but also covers earlier and later years up to the book’s publication.

One of the “best and brightest” featured in Halberstam’s book, former U.S. Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, penned his own book on Vietnam in 1995, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam (Crown Books). McNamara’s best-selling book generated considerable controversy with lots of media time for the former Defense Secretary.

Beyond the literature that covers the Pentagon Papers per se or the decision making at that time, there is of course, a vast array of works on the history of the Vietnam War from multiple perspectives. Among these, for example, are: Frances FitzGerald’s 1975 book, Fire in the Lake: The Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam, and Stanley Karnow’s 1984 book, Vietnam: A History (Viking), billed at the time as “the first complete account of Vietnam at war” (This book was also used as a basis for the long form PBS TV series of the same title).

Among books taking a critical look at Vietnam policy making and military strategy is H.R. McMaster’s 1998 book, Dereliction of Duty: Johnson, McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam – one of many probing the whys and wherefores of U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

Neil Sheehan, the former New York Times reporter that broke the early Pentagon Papers stories, also wrote an award-winning 1988 book on the war, A Bright Shining Lie:John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam (Random House), which probes the Vietnam War through the experiences of John Paul Vann, a U.S. military advisor there in the early 1960s who became increasingly critical of U.S. military command and tactics used in the war.

Another Vietnam book by Mark Bowden published in 2017 focuses on one of war’s seminal military engagements during the Tet Offensive: Hue 1968: A Turning Point of the American War in Vietnam (Atlantic Monthly Press). The titles presented here and above are only samples; not by any means an exhaustive listing of the much larger universe of U.S./Vietnam analysis and the politics of that period.

TV & Hollywood. In September 2003, a television film, The Pentagon Papers, was the first in that arena to explore the Pentagon Papers episode. It aired on the FX cable TV channel. The film is about Daniel Ellsberg and the events leading up to the publication of the Pentagon Papers. It documents Ellsberg’s life starting with his work at the RAND Corporation, and ends with the mistrial in the Ellsberg-Russo espionage case. The film stars James Spader as Ellsberg and cast that also includes Claire Forlani, Alan Arkin, and Paul Giamatti (Rod Holcomb director,Joshua D. Maurer executive producer).

In 2009, a documentary film directed and produced by Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith, titled, The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers. The film had a four-month theatrical run and in 2010 it was shown on the PBS series POV, for which it won a Peabody Award. It was also nominated for an Oscar in the documentary film category and won more than a dozen other film festival and other awards. It features Ellsberg and explores the events leading up to the publication of the Pentagon Papers. One Washington Post reviewer of the film called it: “Compelling… (a) gripping mix of politics, history and the derring-do of one of the era’s most audacious capers…deservedly Oscar nominated.” Here’s the trailer for that documentary:

An earlier documentary on the Vietnam war – Hearts and Minds of 1974 (which won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature that year) – is also relevant to this period and its history, and includes interviews with Ellsberg and other major figures involved in U.S./Vietnam policy making and military operations. And most recently, of course, the 2017, Oscar-nominated Steven Spielberg Hollywood film, The Post, covers the Washington Post portion of the Pentagon Papers episode (trailer available at the top of this story).

The Post

The 2017 Spielberg film – with Meryl Streep portraying the country’s first female newspaper publisher, Katharine “Kay” Graham of The Washington Post, and Tom Hanks playing hard-driving newsroom editor, Ben Bradlee – was released in America at a propitious time; a time when the sitting president, Donald Trump, much like the historic figure, Richard Nixon during the Pentagon Papers controversy, was at war with many news organizations. In addition, by depicting the struggles of a female executive in a powerful business, the Spielberg film also struck a positive chord with women in a time of renewed calls for female equity and empowerment. But perhaps most of all, the film helped drive home the importance of a vibrant and unfettered press, rising to its “fourth estate” responsibilities.

Scene from Steven Spielberg's 2017-18 film, ‘The Post’, showing, at left, Ben Bradlee (Hanks, w/cup), Kay Graham (Streep) next to him, and Meg Greenfield, seated (Carrie Coon), watching news on table-top TV set in the Washington Post newsroom during the tense days of June 1971 as Pentagon Papers publication was being challenged by the Nixon Administration. Click for film DVD.

Spielberg read the screenplay in early 2017 and decided to direct the film as soon as possible. “When I read the first draft of the script,” he told USA Today in November 2017, “this wasn’t something that could wait three years or two years — this was a story I felt we needed to tell today.” Spielberg also explained that it was “a patriotic film” and that he decided to take it on basically because he believes in journalism. Spielberg’s film helped trumpet the importance of a free and feisty press. “It is an antidote to ‘fake news,’ he said of the film. “Those journalists in the movie are true heroes.”

The film began airing in the U.S. in late December 2017, with full release in January 2018. It was chosen by the National Board of Review as the best film of 2017 and was named as one of the top 10 films of the year by Time magazine and the American Film Institute. It also received six Golden Globe nominations (Best Motion Picture – Drama, Best Director, Best Actress – Drama [Streep], Best Actor – Drama [Hanks], Best Screenplay and Best Original Score), and two Academy Award nominations (Best Picture and Best Actress). And while there were some gripes about not giving the New York Times its due in the film, and that “nice guy” Tom Hanks lacked a certain edge to fully portray the Ben Bradlee character, the film nonetheless achieved an important public education role by underscoring the importance of a free and feisty press.

As for the real Pentagon Papers crisis and confrontations of June 1971, it is at least somewhat heartening to know that good people came forward to expose and publish the truth, and that key institutions generally worked as the Founders intended: to help free up vital information for all citizens to access so that democracy can work to keep power in check.

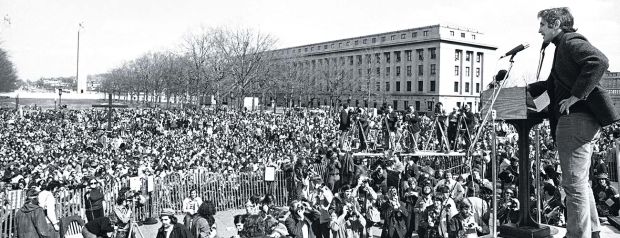

April 1, 1972. Daniel Ellsberg, addressing a crowd at the State Capitol in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania following an anti-war march that ended at the Capitol. (AP photo/Rusty Kennedy)

Still, in the world of government secrecy since 1971, the news is not so good, as Dana Priest, Pulitzer Prize-winning intelligence and Pentagon reporter for the Washington Post has written in a 2016 Columbia Journalism Review article titled, “Did The Pentagon Papers Matter?” Citing a number of cases of “government at work” since the days of the Pentagon Papers, she concludes that “secrecy in government…has continued unabated….” All the more reason for the first-amendment protected press to keep digging and afflicting, and for the rest of us to ensure that they do.

_____________________________

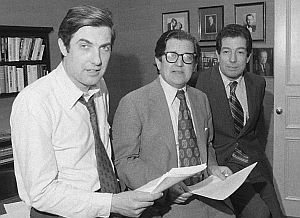

New York Times team that won 1972 Pulitzer Prize for public service for publication of the Pentagon Papers; from left, reporter Neil Sheehan, managing editor A.M. Rosenthal, foreign news editor James L. Greenfield & others. AP photo

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 5 February 2018

Last Update: 22 January 2022

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “The Pentagon Papers: 1967-2018,”

PopHistoryDig.com, February 5, 2018.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Cover used on one version of Quadrangle Books edition of “Pentagon Papers as published by the NY Times,” showing LBJ with Robert McNamara, Dean Rusk, and McGeorge Bundy. |

Originally titled, “United States-Vietnam Relations, 1945-1967,” the Pentagon Papers were designated “Top Secret-Sensitive,” and despite their 1971 disclosure to the press, were not officially “declassified” by the government until June 2011. |

David Rudenstine, Chapter One: “McNamara’s Study,” WashingtonPost.com, from: The Day the Presses Stopped: A History of the Pentagon Papers Case, 1996.

Tim Weiner, “Robert S. McNamara, Architect of a Futile War, Dies at 93,” New York Times, July 6, 2009.

Daniel Ellsberg, Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers, Penguin, 2003.

John Prados and Margaret Pratt Porter (eds), Inside the Pentagon Papers, University of Kansas Press, 2004.

“Pentagon Papers,” History.com.

“Pentagon Papers,” Wikipedia.org.

C-SPAN, “Landmark Cases,” New York Times v. The United States.

George Herring (ed), The Pentagon Papers, McGraw-Hill, 1993.

Tom Olipant, “Only 3 Have Read Secret Indochina Report; All Urge Pullout,” Boston Globe, March 7, 1971, p. 1.

Neil Sheehan, “Vietnam Archive: Study Tells How Johnson Secretly Opened Way to Ground Combat,” New York Times, June 15, 1971, p. 1.

Neil Sheehan, A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam, Random House, 1988.

Hedrick Smith, “Vast Review of War, Set Up by McNamara, Took a Year But Leaves Gaps,” New York Times, June 13, 1971, p.1.

Fred P. Graham, “Argument Friday; Court Here Refuses to Order Return of Documents Now; Judge Halts Times Series on Vietnam for 4 Days,” New York Times, June 16, 1971.

Editorial, “Vietnam: The Public’s Need to Know…” Washington Post, June 17, 1971.

Michael Getler, “Pentagon Reclaims Rand Copies of Viet Study,” Washington Post, June 22, 1971, p. A-10.

“Courts Continue Post, Times Ban; Globe Restrained,” Washington Post, June 23, 1971, p. A-1.

Robert M. Smith, “F.B.I. Men Visit Congressman on Papers He Holds,” New York Times, June 23, 1971, p. 22.

“Post’s Brief Against Enjoining Series on Vietnam,” Washington Post, June 23, 1971, p. A-14.

Michael Getler, “Secrecy Rule Review Was Sought by Nixon,” Washington Post, June 23, 1971, p. A-1.

Linda Charlton, “Ellsberg, On TV, Blames U.S. for 25 Years of War,” New York Times, June 24, 1971, p.1.

Max Frankel, “Impact in Washington: Pentagon Papers a Major Fact of Life For All Three Branches of Government,” New York Times, June 25, 1971, p. 12.

Noam Chomsky, Op-Ed, “The Crisis Managers /The War: The Record and the U.S.,” New York Times, June 25, 1971.

Paul L. Montgomery, “Ellsberg: From Hawk to Dove,” New York Times, June 27, 1971, p. 27.

“Hill Gets Secret Files on War,” Washington Post, June 29, 1971, p. A-12.

“Gravel Calls Night ‘Hearing,’ Reads Pentagon Documents,” Washington Post, June 30, 1971, p. A-1.

Hedrick Smith, “Pentagon Papers: Study Reports Kennedy Made ‘Gamble’ Into a ‘Broad Commitment’,” New York Times, July 1, 1971, p. 1.

Sanford J. Ungar and George Lardner, Jr., “War File Articles Resumed,” Washington Post, July 1, 1971, p. A-1.

Fox Butterfield, “Pentagon Papers: Vietnam Study Links ’65 -’66 G. I. Build-Up to Faulty Planning,” New York Times, July 2, 1971, p. 1.

Don Oberdorfer, “Changing Viet Regimes Baffled U.S.,” Washington Post, July 2, 1971, p. A-1.

“The Government vs. The Press,” Newsweek, July 5, 1971, pp. 18, 32.

“Setting a Date,” Newsweek, July 5, 1971, p. 25.

Fox Butterfield, “Vietnam Papers: Doubt Cast on View That the North Imposed War on the South,” New York Times, July 5, 1971, p. 12.

“Round Three: More Pentagon Disclosures,” Time, July 12, 1971, pp. 12-13.

Ken W. Clawson, “Grand Jury Probes Times, Post, Globe,” Washington Post, July 13, 1971, p. A-1.

“Again the Pentagon Papers,” Time, July 19, 1971, pp. 30-31.

“Report from Vietnam (1968) Walter Cronkite,” YouTube.com.

“Vietnam War U.S. Military Fatal Casualty Statistics,” National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Sanford J. Unger, “Daniel Ellsberg: The Difficulties of Disclosure,” Washington Post, Sunday, April 30,1972, pp. D-1,D-4.

Pentagon Papers Stories at The New York Times.

“Top Secret: The Battle for the Pentagon Papers,” TopSecretPlay.org.

“Daniel Ellsberg and the Vietnam War; Timeline,” PBS.org, “The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers,” October. 5, 2010.

“Pentagon Papers: The Secret War,” Time, Monday, June 28, 1971.

Walter Cronkite, “Interview with Daniel Ellsberg,” The CBS Evening News, June 23, 1971.

“Man With the Monkey Wrench,” Time, Monday, June 28, 1971.

John P. MacKenzie, “Court Rules for Newspapers, 6-3; Decision Allows Printing of Stories on Vietnam Study,” Washington Post, July 1, 1971, p. 1.

“New York Times Co. v. United States,” Wikipedia.org.

“Ellsberg: The Battle Over the Right to Know,” Time, Monday, July 5, 1971.

Sanford J. Ungar, “Expurgated Pentagon Papers Go on Sale to Public Monday; 12-Volume U.S. Edition Of War Study Readied,” Washington Post, September 22, 1971, p. A-1.

Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, “Break-In Memo Sent to Ehrlichman,” Washington Post, June 13, 1973, p. A-1.

Joseph Kraft, “The Plumber’s Assignment: Destruction of Ed and Ted in `72,” New York Magazine, May 13, 1974.

“Text of Ruling by Judge in Ellsberg Case” (re: “plumbers” break-in case of Ellsberg’s former psychiatrist), New York Times, May 25, 1974, p. 13.

Egil Krogh, Op-Ed, “The Break-In That History Forgot,” New York Times, June 30, 2007.

Transcript, “The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons From the Life of Robert S. McNamara” (documentary film, 2004), ErrolMorris.com.

Seymour M. Hersh, “Kissinger and Nixon in the White House,” The Atlantic, May 1982.

Jordan Moran, “Nixon and the Pentagon Papers: Why President Richard Nixon Was Deeply Concerned—Perhaps Even Obsessed—With Leaks Related to Johnson Administration Policies,” The Miller Center, University of Virginia, 2017.

Matthew V. Storin, “A Victory for the Globe and the Press,” Boston Globe, June 22, 2008.

“Daniel Ellsberg,” Wikipedia.org.

Benjamin C. Bradlee, “Big Ben: The Pentagon Papers,” Washington Post, September 17, 1995.

Tim O’Rourke, “Chronicle Covers: When the Pentagon Papers Changed the Nation,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 24, 2016 Updated: September 2, 2016

Warren R. Ross, “A Courageous Press Confronts a Deceptive Government: Beacon Press and the Pentagon Papers,” UUWorld.org (Unitarian Universalist Association), September 3, 2001.

Mike Gravel, A Political Odyssey: The Rise of American Militarism and One Man’s Fight to Stop It, Forward by Daniel Ellsberg, New York: Seven Stories Press, January 4, 2011.

Michael Mello, “Nixon Library to Make Pentagon Papers Public,” Orange County Register, May 28, 2011.

T.J. Ortenzi, “The Pentagon Papers Are Released in Full to the Public,” Washington Post, June 13, 2011.

John Prados (ed.), “The Pentagon Papers: White House Telephone Conversations,” National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 348, National Security Archive (non-governmental, George Washington University, Washington, DC), Posted, June 10, 2011; Updated, June 13, 2011.

Press Kit, “The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers,” A film by Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith, MostDangerousMan.org, 2009.

“The Purloined Pentagon Papers and Prior Restraint: The Press Prevailed!,” St. John’s Law Review, Vol.46: Issue 1, Article 6, 2012.

Jake Kobrick, Research Historian, “The Pentagon Papers in the Federal Courts,” Edited by the Federal Judicial Center for Federal Trials and Great Debates in United States History, Federal Judicial History Office, Federal Judicial Center, Washington, DC, 2014.

James C. Goodale, “Tricky Dick vs. the New York Times: How Nixon Declared War on Journalism,” Salon.com, February 23, 2014.

Dana Priest (Washington Post reporter), “Did the Pentagon Papers Matter?,” Columbia Journalism Review, Spring 2016.

Sanford J. Ungar, “45 Years After the Pentagon Papers, a New Challenge to Government Secrecy,” Washington Post, June 12, 2016.

“Pentagon Papers: Secret Decisions That Altered the Vietnam War,” U.S News & World Report, June 13, 2016.

“The Post (film),” Wikipedia.org.

Rick Goldsmith, “The Pentagon Papers Revisited,” Documentary.org, December 20, 2017.

Christopher Orr, “The Post Is Well-Crafted but Utterly Conventional,” The Atlantic, December 22, 2017.

Ed Rampell, “Raiders of the First Amendment: Spielberg’s “The Post” is Masterful Storytelling Starring Free Speech—and a Woman Leader,” The Progressive, December 23, 2017.

Michael S. Rosenwald, “Fact Checking ‘The Post’: The Incredible Pentagon Papers Drama Spielberg Left Out,” Washington Post, December 23, 2017.

Anna Diamond, “What The Post Gets Right (and Wrong) About Katharine Graham and the Pentagon Papers,” Smithsonian.com, December 29, 2017.

“Spielberg’s ‘The Post’: How 1970s Politics Resonate with Today’s Era of ‘Fake News’,” DW.com, January 11, 2018.

_________________________________