In late June 1969, the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, Ohio caught fire — a river long polluted with oily wastes, chemicals, and debris. In fact, it was at least the 13th time the Cuyahoga River had caught fire since the 1860s. The 1969 fire, however, coming at a time of emerging national concern over pollution, made big news and became something of a famous disaster. The incident helped give momentum to a newly emerging national environmental movement. Only months before, on the beaches of Santa Barbara, California, an oil spill from a Unocal Oil Company offshore rig in January 1969, had soiled some 30 miles of California coastline, killing sea birds and other wildlife. Oil industry pollution and oily wastes were part of the Cuyahoga River concoction as well, described by an August 1969 Time magazine story as being “chocolate-brown, oily, [and] bubbling with subsurface gases.”

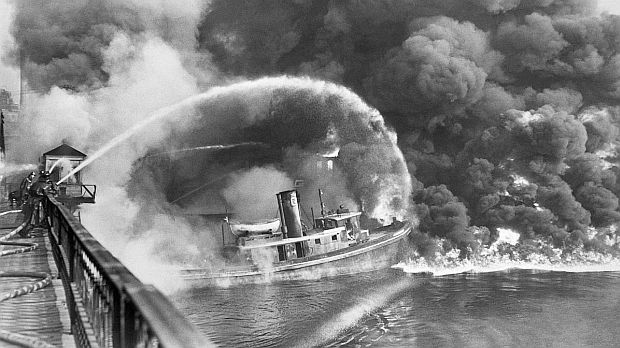

Nov. 3rd, 1952. Fireman on railroad bridge apply water to tug boat ‘Arizona’ amidst flames from the burning Cuyahoga River. Original United Press photo caption reported that “fire started in an oil slick on the river, swept docks at the Great Lakes Towing Co., destroying three tugs, three buildings and the ship repair yards.” (photo mistakenly used by Time magazine as 1969 fire).

In fact, it was the August 1969 Time magazine story that helped bring national attention to the Cuyahoga River and nearby Lake Erie into which it flowed, both of which became poster images for the severe water pollution of those times. (Time magazine wasn’t alone, however. A New York Times story of June 28, 1969 bore the headline: “Cleveland River So Dirty It Burns.”).

U.S. Senator Gaylord Nelson (D-WI), a promoter of the first Earth Day in 1970, would later invoke the Cuyahoga-in-flames as an example of the nation’s most severe environmental disasters. Carol Browner, head of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in the 1990s, would also recall in speeches the impression that images of the burning Cuyahoga had made on her. But the Cuyahoga River fire of June 1969 wasn’t the worst the river had experienced. A 1952 fire – shown in the two photos here – was much worse. Time magazine in its August 1969 story, had used one of those photos, incorrectly attributing it as the 1969 fire.

Another photo of the burning Cuyahoga River from the November 1952 fire, showing a broader expanse of the river area and nearby storage tanks on the far edge of photo.

Turns out, there is a long history of Cuyahoga River fires – at least a dozen or more dating from the 1860s – several of which resulted in more damage than the 1969 incident. More on those in a moment. Still, when the June 1969 Cuyahoga River fire occurred, many people found it surprising that pollution could be so bad that a river would burn. That wasn’t supposed to happen. “[A] river lighting on fire was almost biblical,” said Sierra Club President Adam Werbach referring to the Cuyahoga fire during a CNN interview some years later. “And it energized American action because people understood that that should not be happening.”

|

“Burn On” There’s a red moon rising There’s a red moon rising There’s an oil barge winding There’s an oil barge winding Cleveland, city of light, city of magic Burn on, big river, burn on Now the Lord can make you tumble Burn on, big river, burn on |

The Cuyahoga’s plight – and particularly its association with oil pollution – caught the attention of singer/ songwriter Randy Newman, who penned a famous song about the river’s tendency to catch fire. “Burn On” was the name of the song, which Newman released with his 1972 hit album, Sail Away, an album brimming full of musical satire. Newman’s river song, however, was quite on the mark, conveying at least some of the history and causes of the Cuyahoga River’s pollution problem.

Music Player

“Burn On”-Randy Newman

Newman would explain that he was spurred to write the song after seeing news reports about the 1969 fire. To be fair, by the early 1970s, there were no more fires on the Cuyahoga, though it remained severely polluted for at least another decade. The cleanup of the river had begun by the time of Newman’s song – though ever so slowly, and slogged on for many years thereafter. Still, Newman’s song captured the historical demise of the river and one of its primary culprits, oil. His lyrics at the end of the song also captured the “unnatural” act of a river burning:

Now the Lord can make you tumble

Lord can make you turn

The Lord can make you overflow

But the Lord can’t make you burn

In later years, other musicians would also write music referencing the river, including REM’s. “Cuyahoga” of 1986 and Adam Again’s “River on Fire” of 1992. More on these songs a bit later.

The Cuyahoga River watershed is located in Northeastern Ohio. The river travels about 100 miles from its headwaters in rural Geauga County where it begins as two bubbling springs, then winding its way to Cleveland where it drains into Lake Erie. Named “the crooked river” by native Americans, “Cuyahoga” is an Iroquoian word, befitting the river’s turns and changing course.

Map of the Cuyahoga River watershed, showing the river's many tributaries and its "U" shaped course on its way to Cleveland and Lake Erie.

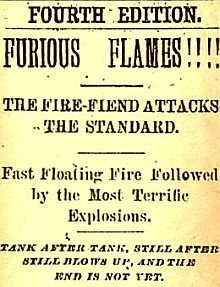

Cleveland Press headlines, circa 1883.

Prior to the fire, on Friday, February 2, 1893, Cleveland had a combination of rising temperature and torrential rains that melted existing snow, producing some of the worst floods in the city’s history. Much of the Flats area and the Cuyahoga River valley were in flood stage. But then came the fire. It began at the Shurmer & Teagle Refinery. However waste oil from a Standard Oil source upstream on Kingsbury Run had been leaking for hours. As reported in Cleveland’s Greatest Disasters: “One by one, nine enormous Standard Oil storage tanks, each containing from five to 16,000 barrels of oil, kerosene, or gasoline blew up over the next 12 hours, adding thousands of additional, lethal gallons to the inflammable torrent rushing toward downtown Cleveland. At one point, no fewer than seven oil tanks were burning at once.” The blaze went on for three days, and Cleveland was nearly a goner, saved by the blocking action of a jammed-up culvert and heroic firemen battling the inferno. By Monday, February 5th, firemen were still pouring water on the various fires. In the end, the damage included nine large storage tanks, 30 stills, and other Standard Oil property. Standard alone had between $350,00 and $300,000 in losses, with all other businesses suffering losses of about $500,000.

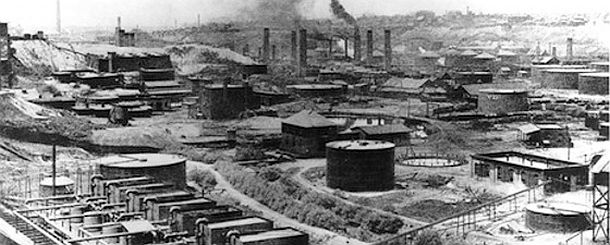

A portion of the Standard Oil refining complex in Cleveland, Ohio, as photographed in 1899.

Still more oil and waste fires occurred on the Cuyahoga River in later years. Four years after the 1883 blaze there was another of lesser note, and perhaps others unrecorded. In 1912, a spark from a tugboat on the Cuyahoga ignited oil leaking from the Standard Oil cargo slip, triggering several explosions and a raging inferno. That fire killed five men and destroyed several boats. In 1914 a river fire reportedly threatened downtown Cleveland until a change in the wind altered its course. A fire in 1922 ignited in the same area as the 1912 Standard Oil dock fire. And in 1936 the river ignited and burned for five days. An ore carrier was damaged by a 1941 river fire. Other fires occurred in 1930, 1948, 1949, 1951. Then came the big one – the 1952 fire – which Jonathan Adler, environmental historian at Case Western Reserve University, describes in a 2003 Fordham Environmental Law Journal article on the history of Cuyahoga River pollution. Adler also describes the events leading up to the fire:

Nov. 2, 1952: Headlines in a Sunday edition of the Cleveland Plain Dealer tell of an oil-slick fire on the Cuyahoga River.

…In 1952, leaking oil from the Standard Oil Company facility was accused of creating, “the greatest fire hazard in Cleveland,” a two-inch thick oil slick on the river. In spots, the slick spanned the width of the river. Although many companies had taken action to limit oil seepage on the river, others failed to cooperate with fire officials. It was only a matter of time before disaster struck. On the afternoon of November 1, 1952, the Cuyahoga ignited… near the Great Lakes Towing Company’s shipyard, resulting in a five-alarm fire. The next morning’s Cleveland Plain Dealer led with a banner headline, “Oil Slick Fire Ruins Flats Shipyard.”[ shown at right]. Photos taken at the scene are incredible; the river was engulfed in smoke and flame. Losses were substantial, estimated between $500,000 and $1.5 million, including the Jefferson Avenue bridge. The only reason no one died was that it started on a Saturday afternoon, when few shipyard employees were on duty.

1951: Oil Burning in the Cuyahoga River, located in the downtown Cleveland Flats area. |

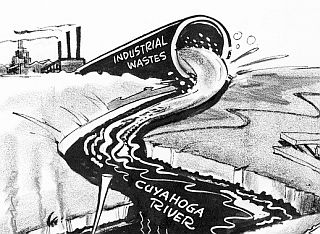

July 1964: Portion of a Bill Roberts’ Cleveland Press cartoon depicting industrial pollution on the Cuyahoga River. |

Circa 1960s. Cleveland reporter, Richard Ellers, dipping his hand in the Cuyahoga’s oily soup, was surprised by its thickness. |

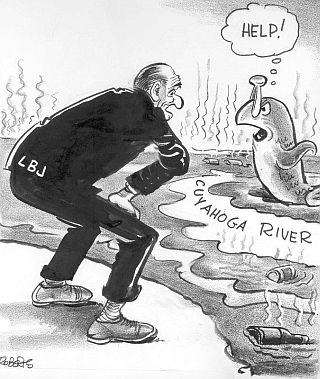

1960s: A Cleveland Press cartoon from Bill Roberts has a distressed fish from the polluted Cuyahoga River seeking help from President Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ). |

September 1964: Councilmen Edward F. Katalinas (left), Henry Sinkiewicz, and John Pilch examine oil-soaked white cloth dipped in the Cuyahoga. Photo, Cleveland Press. |

June 23, 1969: Photo of fire boat attending to hot spots and bridge timbers following Cuyahoga River fire the day before. |

June 23, 1969: Cleveland Mayor Carl Stokes, center, and Ben Stefanski, city utilities director, right, during press conference near site of previous day’s Cuyahoga River fire. |

The Cleveland Plain Dealer, reporting on the 1952 fire, quoted Cleveland Fire Prevention Chief Bernard W. Mulcahy on the front page saying: “We have photographs that show nearly six inches of oil on the river. Our reports show the oil there comes from three sources: Oil brought down Kingsbury Run, from Standard Oil Co., and from Great Lakes Towing itself.”

The fire of 1952 wasn’t the last time the Cuyahoga or its environs would catch fire. Another smaller blaze had occurred a year earlier in the Cleveland Flats area, shown in the photo at left. But the big 1952 fire may have been a turning point, as some environmental historians see it – the point at which local citizen ire is aroused about the problem, with efforts aimed at bringing about change. Still, it would be years before the local recognition and the local resolve would generate the political will at the state and federal levels to write the laws and commit the funding needed to impose standards and clean things up. One preventive measure that was sometimes used along the river in the 1950s and 1960s was the use of a patrolling fireboat to check for oil slick build-ups, especially near bridges, and try to clear those away with high-pressure water hoses.

During the mid-1960s, the Cuyahoga’s pollution drew the attention of Cleveland Press cartoonist Bill Roberts, who did several cartoons on the river and nearby Lake Erie. A few journalists were active as well. Cleveland Plain Dealer reporter Richard Ellers was shown in one 1960s news photo dipping his hand in the Cuyahoga’s goop. And by 1964, a trio of Cleveland city councilmen was photographed retrieving an oil-soaked white cloth they had just dipped in the polluted river.

Cartoonist Bill Roberts also did a mid-1960s Cleveland Press cartoon showing President Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ) listening to the plea of a Cuyahoga River fish amid pollution and the river’s stench, suggestion being that federal help was needed. But despite the fact that federal laws such as the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899 and the 1965 Federal Water Pollution Control Act were on the books, there was little use or effective enforcement of those laws. Yet, federal reports, such as one issued in October 1968, identified the Cuyahoga as one of the most heavily polluted rivers in the nation.

By November 1968 there were plans drawn up in Cleveland to upgrade the city’s sewer systems, as an impressive $100 million bond issue for that purpose had been approved by voters. But then came the fire of 1969.

Fire of 1969

On Sunday, June 22nd, the Cuyahoga caught fire for what was believed to be the 13th time in its history, depending on how many fires were actually counted and/or reported. A slick of oily debris caught fire that day near the Republic Steel operations after a spark from an overhead rail car ignited it. As the burning slick floated down the Cuyahoga, it made its way under the wooden bridges of two key railroad trestles and set them on fire. At times during the blaze, flames climbed as high as five stories, according to Battalion 7 Fire chief Bernard E. Campbell, cited in the Cleveland Plain Dealer the next day. A fireboat battled the flames on the water while fire trucks and firemen from three battalions fought the fire on the trestles, where they soon brought the fire under control. At the time, Campbell reported that a bridge belonging to Norfolk and Western Railway Co. sustained $45,000 damage, closing both of its tracks. The other, a one-track trestle, remained opened. The fire did $5,000 damage to the timbers of this bridge, a Newburgh & South Shore Railroad Co. crossing.

On the day following the fire, June 23, 1969, the Cleveland Plain Dealer ran a photo that showed a fire boat crew hosing down hot spots and smoldering timbers at one of the railroad bridges. Cleveland Mayor Carl Stokes also held a press conference that day using the charred railroad bridge as part of his backdrop. Along with Ben Stefanski, city utilities director, Stokes promised to fight for a cleaner river. He also announced that he was filing a formal complaint with the state, claiming that a clean river was beyond the city’s control. “We have no jurisdiction over what’s dumped in there,” he told The Plain Dealer that day.

In point of fact, the state of Ohio, like other states, did issue pollution discharge permits to industry, permits which purported to set discharge limits, but these were essentially “permits to pollute” and were rarely enforced. The federal government was no better. Even though federal pollution control laws had been enacted in 1949 and 1965, these were very weak laws, with little money attached, and little real help to the states. Another older federal law – the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899, also known as the “Refuse Act ” – had viable provisions of enforcement, and was even upheld in one 1966 Supreme Court case for oily wastes, but it too was rarely invoked. At his press conference, Cleveland Mayor Carl Stokes had criticized the federal government, noting their jurisdiction over the river for interstate commerce.

Meanwhile, the notoriety of the Cuyahoga’s June 1969 fire soon traveled around the country, primarily due to the August 1969 Time magazine story. Time ran a brief story describing the polluted river as “chocolate-brown, oily, [and] bubbling with subsurface gases.” The Cuyahoga, said Time, “oozes rather than flows.” But Time also incorrectly used a dramatic Cleveland Plain Dealer photo from the earlier 1952 fire showing firemen on a railroad bridge battling a blazing tugboat on the river (photo used at the top of this story). Time’s mis-casting of the photo as the 1969 fire appears to have helped spread that impression of the blaze to other news organizations and the general public, furthering “the legend” of the 1969 fire. Still, the river had burned in any case, and that’s what helped ignite calls for action on water pollution nationwide.

Earth Day 1970

The first Earth Day of April 22, 1970, which launched the modern environmental movement, brought demonstrations by some 20 million Americans in towns and cities across the country. The event in New York City brought out thousands who thronged 5th Avenue as far as the eye could see. The demonstration made the front page of the New York Times the next day with headline, “Millions Join Earth Day Observances Across the Nation” (photo below).

A throng of thousands along New York City’s 5th Ave., as far as the eye could see, came out for the Earth Day demonstration of April 22nd, 1970, resulting in front-page coverage the next day. Source: New York Times.

In Cleveland, a march to the Cuyahoga River by Cleveland State University students protesting the river’s pollution was also one of the demonstrations that day. And the Cuyahoga River fire of June 1969 would also be invoked in more than few Earth Day speeches and news accounts that day. Later in 1970, the Cuyahoga received more attention when National Geographic included the river as part of its December 1970 issue and cover story devoted to “Our Ecological Crisis.” The magazine ran a short story and graphic of a six-mile segment of the Cuyahoga showing how it received polluted wastes from steel mills, chemical plants, and other industries along its banks. Meanwhile, the outlook for the river’s health was not good. One report from the Federal Water Pollution Control Administration at the time of the 1969 fire offered this assessment: “The lower Cuyahoga has no visible signs of life, not even low forms such as leeches and sludge worms that usually thrive on wastes.” But change was on the way.

Dec. 4, 1970: At White House ceremony in Wash., D.C., William Ruckelshaus is sworn in as head of EPA as President Richard Nixon looks on. Photo, Charles Tasnadi/AP.

The U.S. Congress, meanwhile, was churning out tougher environmental laws – one of which was the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, also known as the Clean Water Act. This law – first passed by Congress in October 1972, was vetoed by President Nixon,The Clean Water Act of 1972 sought to make all U.S. waterways “fishable and swimmable” by 1985. but finally became law after the House and Senate successfully over-rode the President’s veto on October 18, 1972. The Clean Water Act — aimed at making all U.S. waterways “fishable and swimmable” by 1985 — totally revised water pollution law and regulation, shifting the control mechanism to “effluent limitations” with a long-range goal of “zero discharge.” More pollution control money eventually came to states and cities. In Ohio, meanwhile, the Ohio EPA was created on October 23, 1972, combining environmental programs that were previously scattered throughout several state departments. And in Cleveland, the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District took over sewer operations for the city in the early 1970s and the long, hard fight to cleanup the Cuyahoga began. Progress, however, would not come overnight.

|

“Cuyahoga in Song” In addition to Randy Newman’s “Burn On, Big River” of 1972, included earlier, other musicians have also used the Cuyahoga in song. In 1986, the group R.E.M. released a song titled “Cuyahoga,” which offers a kind of lamentation for a lost river, noting at one point, “we burned the river down.” Music Player But the R.E.M. song is also about the river as a nostalgic place; a place where “we swam;” a place where photographs were taken and memories made — a place sadly, now gone; a place degraded. Among those lyrics are, for example: This is where we walked, In 1992, the river’s burning was still present enough in cultural memory for Adam Again, an alternative rock band, to use the river in a metaphorical way, so stated in their song, “River on Fire.” This song appears to offer a parallel between a possible disaster in a personal relationship to the actual disaster that was the Cuyahoga burning. Some of the ending lyrics in that song are as follows: …I could be happy, I know a lot about the history And apart from music, there is also at least one beer named after the Cuyahoga’s infamous history – “Burning River Pale Ale” (see below). |

As the Federal Clean Water Act first came into effect, EPA became the primary enforcer, sharing that role with state and cities in later years — in Cleveland’s case, the regional sewer district. Along the Cuyahoga, stiff fines were levied for violators and some polluters were put out of business. Local and state citizen and environmental groups helped as well, dating to the Kent Environmental Council in 1970 which held one of the Cuyahoga River clean-ups. Dozens of other groups would form in later years, including Friends of The Crooked River, and others.

Long Fight

Still, by 1984, when biologists for the Ohio EPA began counting fish in the middle-to-lower section of the Cuyahoga River — the worst polluted section from Akron to Cleveland — they found very few. In fact, they found less than a dozen fish in total, and even some of those were pollution-tolerant species such as gizzard shad, while others had deformities. But gradually, things began to turn for the better.

In 1988, as the U.S. and Canada began working jointly on cleaning up the Great Lakes, and identifying contributing problem areas, various local organizations were created to help with the effort, focusing on those rivers contributing most to the problem. Among the organizations created was the Cuyahoga River Community Planning group of Cleveland, known today as Cuyahoga River Restoration, which continues to work to bring the Akron-to-Cleveland segment of the Cuyahoga up to Great Lakes Water Quality Act goals and standards.

At first, improvements came mostly in the upper reaches of the river in its more rural counties. By the summer of 2008, unofficial surveys from Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District were finding high levels of aquatic life in the river. EPA, then following up with its own survey, reported 40 different fish species in the river, including steelhead trout, northern pike, and other clean-water fish.

Since the 1969 Cuyahoga River fire, the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District has invested more than $3.5 billion in new sewer systems to help clean up the river. Over the next thirty years or so, it is projected that Cleveland will spend another $5 billion or more to insure the upkeep of its wastewater system. The river is now home to about sixty different species of fish, and there has not been another river fire since 1969.

In 1998, EPA designated the Cuyahoga as one of 14 American Heritage Rivers, those which have played a key role in shaping the nation’s environmental, economic and cultural landscape.

In 2000, some 51 square miles of river valley between Akron and Cleveland was established as the Cuyahoga Valley National Park. This section of river valley was previously designated a national recreation area in 1974. Today the park includes forests, wetlands, canals, a waterfalls, and more than 125 miles of hiking trails, including the Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail, which follows the route of the former canal. In some sections of the park, bald eagles and otters have returned to the river.

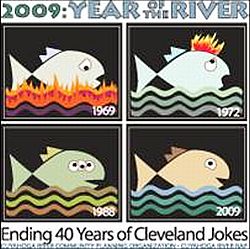

Cuyahoga River graphic depicting four decades of progress and calling for an end to all those bad Cleveland jokes. (Cuyahoga River Restoration).

EPA officials, however, denied the request, though commending the community on progress made, but saying there was still some distance to go. One graphic at that time also called for an end to all the bad jokes about Cleveland centered around the Cuyahoga’s past history.

Meanwhile, in the Cleveland Flats area of the river, business investors found the area attractive enough to begin converting parts of the abandoned industrial landscape into more appealing urban uses. And along the Cuyahoga, things improved as well.

As Jane Goodman, executive director of Cuyahoga River Restoration, reported in August 2018: “…[N]ow we’re on to providing habitat for the several dozen pollution-sensitive fish species that now live in and migrate through the industrial channel. And the Flats is teeming with upscale housing, dining, and entertainment venues, parks and trails, and people kayaking, rowing, paddleboarding, fishing, and watching the gigantic ships taking ore to the steel mill and gravel to the materials sites.” And among visitors, tourists, and Cleveland enthusiasts patronizing the various pubs and restaurants in the Flats district today, there may well be a few venturesome souls imbibing in a local beer named “Burning River Pale Ale.”

More Than a Beer…

Great Lakes Brewing Co.'s "Burning River Pale Ale," seems to have helped elevate the Cuyahoga River to iconic status on behalf of environmental good.

“The year 2019 will be the 50th anniversary of the Cuyahoga River catching on fire,” Pat Conway has stated. “The publicity from that incident spurred all of the environmental legislation that followed. I would love to see this Burning River Fest become the largest environmental celebration in the country by that time.” Other Cleveland and Cuyahoga organizations are also planning special events. Cuyahoga River Restoration, for example, is using the tagline: “50 years of Cuyahoga River recovery. No fires. Just fish, freight, and fun” for its year-long celebration, and will also publish a book of local perspective and remembrance.

The burning Cuyahoga, then, has become something of a cultural icon and continuing spur to civic and environmental improvement — an image of infamy now turned to good advantage. So yes, in the words of Randy Newman’s famous song – but for an altogether different, good, and honorable purpose – “burn on big river, burn on.”

Additional environmental stories at this website can be found at “Environmental History,” a topics page with links to stories on pesticides, air pollution, toxic chemicals, coal mining, oil refining, and other issues. See also at this website the “Politics & Society” page or the “Annals of Music” page for stories in those categories. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what your find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 12 May 2014

Last Update: 18 June 2019

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Burn On, Big River…,” Cuyahoga River Fires,

PopHistoryDig.com, May 12, 2014.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

1960s: Citizens of Cleveland, Ohio protest over the pollution of Lake Erie. Source: Cleveland Foundation. |

December 1937: Aerial view of meandering Cuyahoga River in winter snow wending its way toward Lake Erie at Cleveland, Ohio. photo, National Archives. |

1961: Fireboat on the Cuyahoga River using high-pressure water hoses to clear fire-prone oily build-ups. |

1964: U.S. Congressmen visit pollution problem on the Cuyahoga River; L-to-R: John Blatnik, Charles Vanik & Mike Feighan. Cleveland Press photo. |

River bank warning sign of the Cuyahoga River’s flammability, circa 1950s-1960s period. |

Cuyahoga River on fire, possibly 1952 fire. |

Logo/poster for the Burning River Fest, held every summer at Whiskey Island on the Cuyahoga River at Cleveland, Ohio, the proceeds from which help benefit environmental work. |

Robert H. Clifford, “City’s Lake and River Fronts in Constant Peril of Conflagration Without the Protection of Fire Tugs,” Cleveland Press, April 25, 1936, p.1.

Dan Williams, “Rivermen Cite Fire Peril, Ask City for Protection,” Cleveland Press, March 11, 1941, p. 1.

WKYC-TV (NBC Cleveland, OH), The Crooked River Dies, A 1967 public affairs film in the Montage series, at YouTube.com (4:45 clip).

“Oil Slick Fire Damages 2 River Spans,” The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), June 23, 1969, p. 11-C.

“Cleveland River So Dirty It Burns,” New York Times, June 28, 1969.

“America’s Sewage System and the Price of Optimism,” Time, Friday, August 1, 1969.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Cuyahoga River,” EPA.gov.

John Stark Bellamy, II, Cleveland’s Greatest Disasters!: 16 Tragic True Tales of Death and Destruction, Gray & Company, 2009.

Michael D. Roberts, “Rockefeller and His Oil Empire Issue,” IBmag.com, July/August 2012.

Jonathan H. Adler, “Fables of the Cuyahoga: Reconstructing a History of Environmental Protection,” Fordham Environmental Law Journal, 2003.

Jonathan Adler, “Smoking Out the Cuyahoga Fire Fable,” National Review, June 22, 2004.

“Cuyahoga River Put Among the Most Rank,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 3, 1968.

Jack A. Seamonds, “In Cleveland, Clean Waters Give New Breath of Life,” U.S. News & World Report, June 18, 1984, p. 68.

“Sad, Soiled Waters: The Cuyahoga River and Lake Erie,” National Geographic, December 1970.

John Kuehner, “30 Years Ago, Polluted Cuyahoga Had No Fish; Now They’re Thriving,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 18, 2002, p. B-2.

“The Cuyahoga River Fire of 1969,” Pratie .BlogSpot.com, March 16, 2005.

PBS film, The Return of the Cuyahoga, April 2008.

David and Richard Stradling, “Perceptions of a Burning River: Deindustrialization and Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River,” Environmental History, July 2008, pp. 515-35.

Michael Scott, “After the Flames: The Story Behind the 1969 Cuyahoga River Fire and its Recovery,” The Plain Dealer(Cleveland, Ohio), January 4, 2009.

Michael Scott, “Cuyahoga River Fire Galvanized Clean Water and the Environment as a Public Issue,” The Plain Dealer, April 12, 2009.

Michael Scott, “Cuyahoga River Fire Story Comes out a Little Crooked on Way to Getting Tale Straight,” The Plain Dealer, April 12, 2009.

Michael Scott, “Scientists Monitor Cuyahoga River Quality to Adhere to Clean Water Act,” The Plain Dealer, April 12, 2009.

“Year of the River,” Brown Flynn, May 1, 2009.

Joe Koncelik, “Ending 40 Years Of Cleveland Jokes: A River’s Recovery,” Ohio Environ-mental Law Blog, June 14, 2009.

Michael Scott, “U.S. EPA Commends Cuyahoga Cleanup — But Won’t Take River off List of Polluted Waters,” The Plain Dealer, June 22, 2009.

“Fire on the River: Forty Years Later, a Much-Improved Cuyahoga, and Much Work Still to do,” Akron Beacon Journal, Friday, June 26, 2009.

Sharon Broussard (Northeast Ohio Media Group), “EPA Should Take Parts of the Cuyahoga River off the ‘Polluted’ List,” Cleveland.com, July 3, 2009.

Michael Scott, Healthy Fish, Insects Show Cuyahoga River Also Much Healthier,” The Plain Dealer, March 2, 2009 / Updated, January 14, 2010.

Special Series, “Year of the River: A Look at the Cuyahoga River 40 Years After it Caught Fire,” The Plain Dealer, 2011.

Michael Scott, “Cuyahoga River Fire 40 Years Ago Ignited an Ongoing Cleanup Campaign,” The Plain Dealer, March 7, 2011.

James F. McCarty, “Cuyahoga River Sediment Is Getting Less Toxic, Possibly Saving the Region Millions of Dollars,” The Plain Dealer, March 17, 2011.

“Cuyahoga River Pollution Photos,” Cleveland Memory Project, Cleveland State University Libraries, Cleveland, Ohio.

Michael Rotman, “Cuyahoga River Fire,” Cleveland Historical.org, Accessed May 2, 2014.

“Cuyahoga River Restoration,” YouTube .com, Posted by WFN: World Fishing Network (discusses the last 40 years of clean-up, returning fish populations, lower river development, and the Cuyahoga’s designation as one of 14 Heritage Rivers).

“What Would Gaylord Do? An Essay on the Environmental Movement and the Deepwater Horizon Disaster,” The Seventh Fold, May 3, 2010.

Michael Heaton, “Burning River Fest Parties in the Name of the Environment,” The Plain Dealer, July 19, 2012.

Burning River Foundation, Cleveland, Ohio.

Michael Rotman, “Cuyahoga River Fire,” PureWaterGazette.net, July 8, 2013.

Adam Again, “River on Fire,” YouTube.com, posted by Zarbod, uploaded November 2, 2007.

“Cuyahoga River,” Wikipedia.org.

Kevin Courrier, Randy Newman’s American Dreams, ECW Press, 2005.

“R.E.M. – Cuyahoga,” YouTube.com, Posted by Micheleland.

Cuyahoga River Restoration Website (formerly, Cuyahoga River Community Planning), Cleveland, Ohio.

Share The River Website, “Cleveland is a Waterfront City, and We’re Sharing All the Things That Make it a Vibrant and Engaging Space for Residents and Visitors.”

“Cuyahoga (scene),” re: ‘Fire On The Water’ play opening at Cleveland Public Theatre, Cleveland Centennial.blogspot.com, January 30, 2015

“Where The River Burned” (book excerpt), Belt Magazine, April 22, 2016.

________________________