A portion of the DVD cover for the 2011 PBS / American Experience film, “Freedom Riders,” by Stanley Nelson. Click for DVD.

Before it was all over more than 60 “Freedom Rides” would criss-cross the South between May and November of 1961. At least 436 individuals would ride buses and trains to make their point. However, a number of the “freedom riders” were physically assaulted, chased, and/or threatened by white mobs, some beaten with pipes, chains and baseball bats. Many of the riders were also arrested and jailed, especially in Mississippi. Yet these arrests became part of the protest – and in this case, a badge of honor.

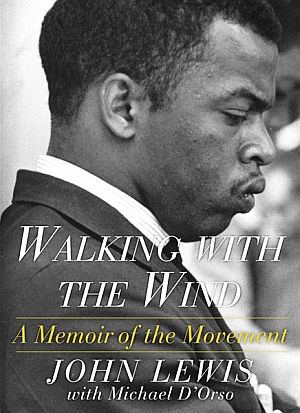

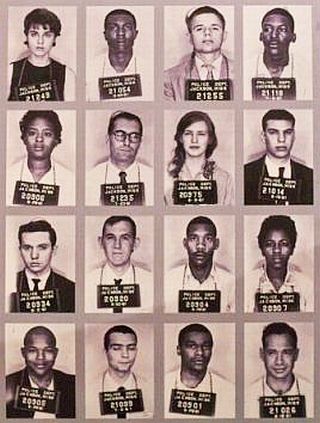

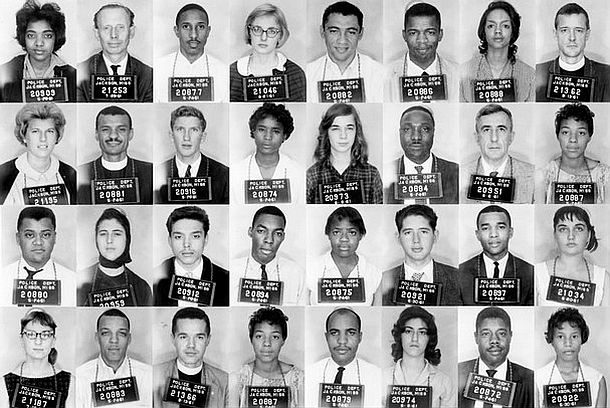

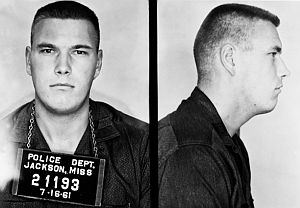

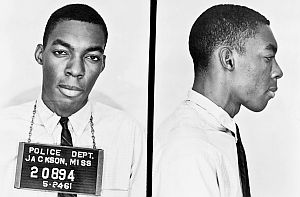

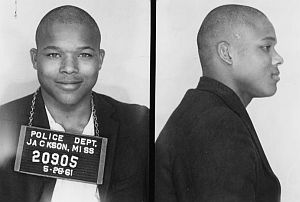

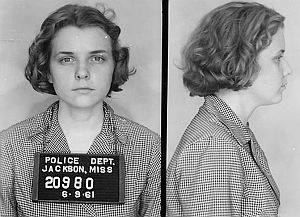

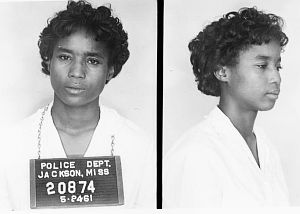

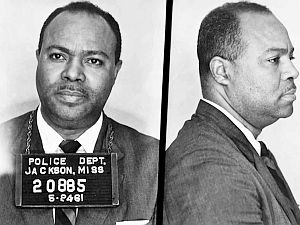

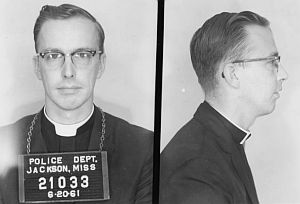

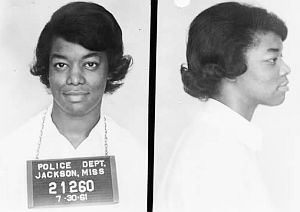

Mug shots of some of the more than 300 “freedom riders” who were arrested in Mississippi during the summer of 1961. More on this part of the story follows later.

The freedom rides of 1961, mostly bus rides, had a legal as well as a moral objective. They were testing two U.S. Supreme Court rulings – Morgan v. Virginia (1946) and Boynton v. Virginia (1960) – rulings that found that segregated public buses and related facilities on interstate transportation routes were unconstitutional and illegal. That meant trains, buses, planes, ferries, and related terminals and waiting rooms. The first case dates to July 1944, when Irene Morgan was arrested in Virginia after refusing to give up her seat on a Greyhound bus while traveling home from Baltimore, Maryland.

Freedom Ride button issued by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE).

In 1961, segregated waiting rooms, fountains & restrooms were common in Southern bus & train terminals, despite Supreme Court rulings striking them down.

Farmer and CORE were also testing the newly-elected Kennedy Administration in Washington – President John F. Kennedy and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy – to see if they would enforce laws banning segregation.

The plan for the first ride was to send volunteers on two buses – one group on a Trailways bus and another on a Greyhound bus – both departing from Washington, D.C. bound for New Orleans, Louisiana. Along the route, there would be stops at bus terminals throughout the south, with the passengers selectively testing the “white only” or designated “negro waiting” areas.

May 4, 1961

First Departure

May 5, 1961: Washington Post story (p. B-4) covers the Freedom Riders’ plan and departure for the first 13 riders.

The Washington Post ran a story on the group’s intentions the following day, May 5th, 1961 on p. B-4 by reporter Elsie Carper. The story, headlined “Pilgrimage Off on Racial Test,” described the group’s trip along with an Associated Press photo of five of the participants looking over a map of their planned route of travel over the next two weeks.

Shown in the photo, from left, were: Edward Blankenheim from Tucson, Arizona; James Farmer, of New York city and director of CORE; Genevieve Hughes of Chevy Chase, Maryland; Rev. Benjamin Elton Cox of High Point, North Carolina; and Henry Thomas of St. Augustine, Florida.

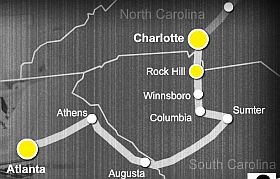

The first leg of the Freedom Ride from Washington made stops in Virginia and North Carolina. Source: PBS / American Experience.

The first leg of their trip included stops at Richmond, Petersburg, Farmville, Lynchburg and Danville in Virginia. Stops in North Carolina included Greensboro, High Point, Salisbury and Charlotte. There were no confrontations with riders at most of these stops. Should trouble occur, however, the Freedom Riders were trained in non-violent tactics and would not fight back. In Charlotte, North Carolina, there was an arrest.

Genevieve Hughes and John Lewis, Rock Hill, S.C.

The second leg of the trip through South Carolina and Georgia included dinner with Martin Luther King in Atlanta. Source: PBS/American Experience.

May 14, 1961

Anniston

In Anniston, at the Greyhound station, a white mob had gathered waiting for the first bus with its Freedom Riders. As it arrived, the mob attacked the bus with iron pipes and baseball bats, breaking some windows and slashing its tires. By the time Anniston police arrived, the bus had taken a fair beating, but no arrests were made. The passengers had remained inside the bus. The Anniston police car escorted the bus out of the station to just beyond the Anniston city limit on a rural stretch of road. There, because of the punctured tires, the bus was forced to pull off the road near the Forsyth & Son grocery store. This was about five miles west of Anniston.

Mothers’ Day, May 14, 1961, as Greyhound bus carrying Freedom Riders and other passengers burns after being fire-bombed by white mob that attacked the bus and some riders near Anniston, Alabama.

The fire-bombed bus at Anniston, Alabama produced thick smoke that filled the cabin, choking escaping riders. |

The fire on the mob-burned bus at Anniston, Alabama was eventually put out, but the bus was totally destroyed. |

Freedom Riders Jimmy McDonald, center, Hank Thomas, foreground, and regular passenger Roberta Holmes, right, behind Thomas, after bus burning melee, May 14, 1961. |

Fireman going through remains of bus, following fire. |

Map showing route of two Freedom Ride buses traveling from Atlanta, GA to Anniston and Birmingham, Alabama. |

The white mob, meanwhile, had pursued the bus, with a line of some thirty cars and pickup trucks following behind – with at least one car later weaving back-and-forth in front of the bus to slow it down. After the one local police car disappeared, the mob resumed its assault on the bus and its occupants. One attacker hurled a firebomb into the bus. Some reports indicated that the bus door was held shut from the outside preventing riders from exiting, as some of the mob yelled, “burn them alive!” A few of the riders exited through windows.

The bus door was later forced opened, but only after one of the bus fuel tanks exploded, sending some of the mob into retreat. Riders exited gasping for their lives, choking on the thick smoke that had filled the bus.

Riders Beaten

Still, upon exiting the smoke-filled bus, some of the choking Freedom Riders were set upon and beaten by members of the mob. Rider Hank Thomas was one of those beaten with a baseball bat. Some of the mob remained, but a later-arriving state patrolman fired two warning shots into the air, and the mob gradually dispersed.

The Greyhound bus, meanwhile, became completely engulfed in flames and was totally destroyed. The riders on the second bus, the Trailways bus, were still on their way, unaware of what had happened in Anniston.

At the scene in Anniston, importantly was one lone photographer, Joe Postiglione of the Anniston Star, who had been tipped off by KKK members. Postiglione’s photos of the Anniston bus bombing – shown above and at left – were the only still photographs of the incident, and they soon made it over the newswires to newspapers all across the country – some running the photo on the front pages, thereby drawing the first national attention to the Freedom Rides.

Also in Anniston that day was a 12 year-old white girl, Janie Miller, who lived nearby, and after the violence subsided, defied the Klansmen and brought water to the bleeding and choking riders.

“It was the worst suffering I’d ever heard,” Miller would recall in the PBS / American Experience film, Freedom Riders. “I walked right out into the middle of that crowd. I picked me out one person. I washed her face. I held her, I gave her water to drink, and soon as I thought she was gonna be okay, I got up and picked out somebody else.” For daring to help the injured riders, she and her family were later ostracized by the community and could no longer live in the county.

A number of Freedom Riders that day were taken, eventually, to the Anniston Memorial Hospital where one attempt was made, unsuccessfully, by a group of Klansman trying to block the entrance to the emergency room.

KKK on 2nd Bus

Meanwhile, the second bus with Freedom Riders – the Trailways bus – made a brief stop in Anniston at another bus station. At that stop, the bus was infiltrated by some ticketed KKK members who proceeded to restore the “blacks-in-the-back” seating order on the bus by way of brutally beating up two of the Freedom Riders and installing them in the rear seats. These infiltrators stayed on the bus until it arrived in Birmingham, Alabama, slinging verbal abuse at the Freedom Riders en route and promising them a “special reception” in Birmingham.

May 14, 1961

Birmingham

Part of the attacking mob with KKK members at Birmingham, AL, as black bystander George Webb is beaten by several men in the foreground. Photo, Tommy Langston.

The Trailways station had filled with Klansmen and some reporters. When the Freedom Riders exited the bus, they were beaten by the mob, some wielding baseball bats, iron pipes and bicycle chains. White Freedom Riders in the group were especially singled out by the mob, receiving ferocious beatings.

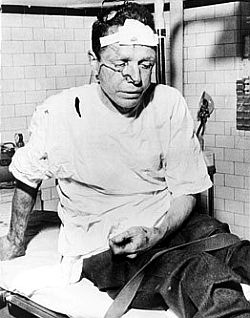

Jim Peck, a 46-year-old white CORE member from New York, and black Freedom Rider Charles Person, a student from Atlanta, both headed for the “whites only” lunch counter, according to plan, as they came off the bus. However, they never made it there.

Jim Peck in hospital after treatment for injuries sustained during mob beating at the Birmingham bus terminal.

Freedom Riders were not the only ones attacked in Birmingham. Innocent bystanders were beaten too, and so were members of the press. As soon as the flashbulb went off for the photo shown above right, the mob took after the photographer, Tommy Langston of the Birmingham Post-Herald. He was caught in the bus station parking lot and beaten and kicked and threatened with pipes. His camera was also smashed to the ground. He later staggered down the street to the Post-Herald building and was later treated at the hospital.

Headline from 'The Montgomery Advertiser' news-paper (Montgomery, AL) tells of Anniston bus burning & mob attacks in Birmingham.

A few of Langston’s colleagues at the Post-Herald returned to the bus station to retrieve his smashed camera to find, amazingly, that the film was still intact. The photo of the melee, shown above, ran the next day on the front page of the Birmingham Post-Herald, one of the few pieces of evidence documenting the mob attack and its participants.

Meanwhile, back in Anniston, hospitalized Freedom Riders were told to leave the hospital as the staff there became afraid of a growing mob. A group of churchmen and others led by Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth headed off around 2 a.m. that night to rescue the hospitalized Freedom Riders in Anniston.

Media Reports

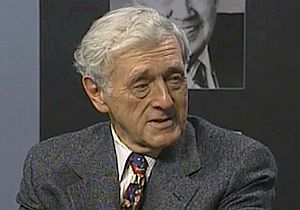

In addition to news reports about the Anniston bus bombing and mob attacks in Birmingham, Howard K. Smith, a national CBS News correspondent, was already in Birmingham at the time of the attacks. He was working on a television documentary investigating allegations of lawlessness and racial intimidation in the Southern city. Smith, a Southerner himself from Louisiana, was trying to determine if the claims he and his network were hearing about were exaggerated or true.

May 1961: CBS newsman, Howard K. Smith, reported on the mob attacks on Freedom Riders that occurred in Birmingham, Alabama.

Smith did deliver news accounts of the bus station melee over the CBS radio network that went out nationally. He would make a series of live radio updates from his hotel room that day. “The riots have not been spontaneous outbursts of anger,” he reported in one broadcast, “but carefully planned and susceptible to having been easily prevented or stopped had there been a wish to do so.” In another he explained: “One passenger was knocked down at my feet by 12 of the hoodlums, and his face was beaten and kicked until it was a bloody pulp.”[i.e., the Jim Peck beating].The “rule of barbarism in Alabama,” said Smith in his commentary, must bow to the “rule of law and order – and justice – in America.” Smith reported the facts of the incident for CBS. “When the bus arrived,” he explained in one report, “the toughs grabbed the passengers into alleys and corridors, pounding them with pipes, with key rings, and with fists,” But he was outraged by what he had witnessed, and stated at one point that the “laws of the land and purposes of the nation badly need a basic restatement.” Smith at the time also did a Sunday radio commentary, during which he was more direct, “The script almost wrote itself,” he would later recall. “I had the strange, disembodied sense of being forced by conscience to write what I knew would be unacceptable.” In his commentary, Smith laid the blame squarely on Police Chief Eugene “Bull” Connor, whose officers had looked the other way during the attack. During that commentary Smith also stated that the “rule of barbarism in Alabama” must bow to the “rule of law and order – and Justice – in America.”

According to historian Raymond Arsenault, author of the 2006 book, Freedom Riders, “Smith’s remarkable broadcast opened the floodgates of public reaction. By early Sunday evening, hundreds of thousands, perhaps even millions, of Americans were aware of the violence that had descended upon Alabama only a few hours before.” At that point, few people had heard of CORE, and fewer still knew what the term ‘Freedom Rider’ meant. But with reports like the one Smith made, more and more of the general population would soon understand what was taking place in the southern part of their country.

By Monday, May 15th, photographs of the burning “Freedom Bus” in Anniston and Birmingham mob scene were reprinted in newspapers across the country. In Washington, D.C., meanwhile, on May 16th an editorial titled “Darkest Alabama” ran in the Washington Post newspaper.A Washington Post edito- rial of May 16, 1961 used the tagline, “Darkest Ala- bama.” The editors, noting the traditions of the old South such as chivalry, hospitality, and kindness, found them notably absent in Birmingham and Anniston, where the busses and Freedom Riders had been attacked. The Post also noted that “Alabama has a Governor who encourages contempt for the Constitution of the United States and who preaches incendiary racist nonsense.” The Post concluded that Americans traveling in Alabama could not be assured of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. “They are quite justified, therefore, in looking to the United States Department of Justice for the protection of their rights as American citizens.” That message was likely read at the U.S. Justice Department and in the White House.

|

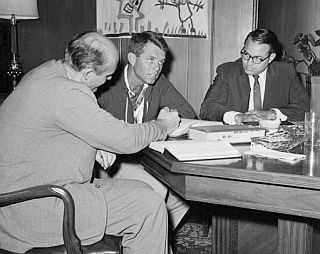

“The Kennedys”  During the violence and unrest of the Freedom Rides in 1961, President Kennedy and Attorney General Robert Kennedy met frequently to deal with the crisis. Although John F. Kennedy (JFK) won the 1960 presidential election by a slender margin, with the black vote playing a key role, he had not been quick to move on civil rights issues in the early months of his administration. Kennedy had been cautious on civil rights as he feared taking action would antagonize southern Democrats – “the Dixiecrats” – a group he needed for both his near-term legislative agenda in Congress, and looking ahead to 1964, for his re-election. (In time, the “Dixiecrat defection” JFK feared would occur, helping elect Richard Nixon in 1968). So the Freedom Rides were among the last thing that he and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy(RFK), wanted to see in 1961. Just a month earlier, Kennedy had gone though the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba. And in May, he was in the midst of preparing for a scheduled June 3, 1961 Vienna Summit with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, the first such summit of his presidential term. So Kennedy’s focus was not on domestic issues, and civil rights, least among these. Journalist Evan Thomas explains in the PBS film Freedom Riders: “The Kennedys, when they came into office, were not worried about civil rights. They were worried about the Soviet Union. They were worried about the Cold War. They were worried about the nuclear threat. When civil rights did pop up, they regarded it as a bit of a nuisance, as something that was getting in the way of their agenda.”  Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, center, conferring with Justice Department assistants, Nicholas B. Katzenbach, left, and Herbert J. Miller, during the May 1961 Freedom Rides. As President Kennedy first learned of the escalating tension around the Freedom Rides, he was not pleased. When reports of the bus burning and beatings in Birmingham reached Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy (RFK), he urged restraint on the part of Freedom Riders. The Kennedys, in fact, had condemned the Freedom Rides as unpatriotic because they embarrassed the nation on the world stage at the height of the Cold War. At one point later that summer, Robert Kennedy had called on the Freedom Riders for a “cooling off period.” James Farmer, head of CORE, responded saying, “We have been cooling off for 350 years, and if we cooled off any more, we’d be in a deep freeze.” Although the Kennedys were initially angered by the Freedom Riders, and thought the bus rides should end, they soon became quite concerned with the incidents and the safety of the riders. Throughout the summer, Robert Kennedy especially, would become heavily involved in federal-state negotiations to protect the Riders – amid repeated attempts to dissuade them from continuing. However, the Administration was in a bit of quandary on just how much the federal government should get involved and what level of force might be needed. JFK, meanwhile, had some political alliances that would prove awkward.  JFK and Alabama Governor, Democrat John Patterson, during a 1960 Kennedy-Johnson campaign rally. During his 1960 presidential bid, JFK had made some political alliances that would come back to haunt him. Alabama’s governor, Democrat John Patterson, was one of these. Patterson had been one of the few southern politicians to endorse JFK for president, doing so early in 1959. Yet, when it came to the Freedom Riders, Patterson was squarely on the side of the segregationists and “states rights,” and he and the Kennedys would spar on the matter through May of 1961. Given the Anniston and Birmingham incidents, the Kennedys worried that there might be more violence in Alabama, and they wanted protection for the Freedom Riders. Governor Patterson had refused to guarantee the Freedom Riders safety. JFK thought at one point he would be able to persuade his old political ally to come around on the matter, diffuse the tensions at the state level, and keep Washington out of the picture. Kennedy had White House telephone operators place a call to Governor Patterson. The governor’s secretary responded that the governor was fishing in the Gulf of Mexico and could not be reached. It was then that Kennedy realized what he was up against, and gave the go-ahead to begin preparing for the possible use of federal marshals.  Alabama Gov. John Patterson, left, confers with Robert Kennedy and two unidentified aides. Photo undated. Robert Kennedy, meanwhile, at the Justice Department, had conferred with a number of assistants on the matter, including Nicholas B. Katzenbach and Herbert J. Miller, shown in the photo above. Kennedy urged all citizens and travelers in Alabama to refrain from actions “which will cause increased tension or provoke violence” in troubled Montgomery. RFK had also sent his longtime friend, Justice Department representative John Seigenthaler, to mediate between the Freedom Riders and southern politicians. A native of Nashville, Tennessee, Seigenthaler had local southern roots that Robert Kennedy hoped would help ease tensions with southern politicians. Seigenthaler went to Birmingham to monitor the situation and ensure that the Freedom Riders would get off safely to their next destination. Other RFK aides and DOJ officials, including John Doar and Deputy Attorney General Byron White, later a Supreme Court justice, would also become involved with the Freedom Rides. |

May 15, 1961: Freedom Rider James Peck, talks with a Dept of Justice official and Ben Cox on plane to New Orleans. Photo, T. Gaffney.

April 1960: Diane Nash, as Fisk University junior with the Rev. Kelly Smith, president of the Nashville Christian Leadership Council. Photo: Gerald Holly, Nashville Tennessean.

Meanwhile, other civil rights activists, realizing the importance of the Freedom Ride, and also seeing the national attention the Anniston and Birmingham incidents had brought to the civil rights movement, began planning to continue the bus rides. The Nashville Student Movement, lead by Diane Nash, decided to send “fresh troops” to Birmingham – replacement riders – to continue what CORE had started. Nash and other civil rights activists began to see that what CORE had put in motion could not be allowed to fail, and should not stop because of violence.

Raised in middle-class Catholic family in Chicago, Nash attended Howard University in Washington, D.C, before transferring to Nashville’s Fisk University in the fall of 1959. Shocked by the extent of segregation she encountered in Tennessee, she became a founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in April 1960. In February 1961 she served jail time in solidarity with the “Rock Hill Nine” — nine students imprisoned after a lunch counter sit-in.

Nash felt that if violence was allowed to halt the Freedom Rides, the movement would be set back years. She pushed to resume the ride and began calling black colleges in nearby states to find replacements for the injured Freedom Riders. On May 17, 1961, a group of eight blacks and two whites – students from Fisk University, Tennessee State University and the American Baptist Theological Seminary – traveled by bus from Nashville to Birmingham, where they would then resume the Freedom Ride from there to Montgomery, Alabama, and then on to Mississippi and Louisiana. However, upon their arrival in Birmingham, they were immediately arrested – “protective custody,” according to police. Later that night, in the early a.m. hours, this group was transported by Birmingham police chief Eugene “Bull” Connor to Ardmore, Alabama near the Tennessee line, and dropped off in a rural area – an area reportedly known for Klan activity. They were told to take a train back to Nashville. After finding refuge with a local black family, they reached Diane Nash who sent a car for them, returning them to Birmingham, where they intended to resume the Freedom Ride.

|

“John Meets Diane”  John Seigenthaler, in later years, would recall his activities during the 1961 Freedom Rides in the 2011 PBS documentary, “Freedom Riders.” John Seigenthaler, a former reporter for The Nashville Tennessean newspaper, had worked with Robert Kennedy in Congress. In 1961, then 32, Seigenthaler became a special assistant in Robert Kennedy’s Justice Department. Dispatched by Kennedy to the south to help diffuse the Freedom Rider tensions, his first task in that crisis was to get the CORE Riders safely on airplanes to New Orleans. When the Riders – after some harassment and verbal abuse along the way – arrived safely in New Orleans, Seigenthaler thought both the Freedom Rides and the crisis were over. Instead, he learned that someone named Diane Nash and others from the Nashville Student Movement planned on continuing what the CORE Riders had started. In the PBS film Freedom Riders, Seigenthaler appears on camera offering his remembrance of that pivotal moment: . . . I went to a motel to spend the night. And you know, I thought, “What a great hero I am. . . . How easy this was. . . I just took care of everything the president and the attorney general wanted done. Mission accomplished.” My phone in the hotel room rings and it’s the attorney general.“Sir, you should know, we all signed our last wills and testaments last night before they left…” Her response was, “They’re not gonna turn back. They’re on their way to Birmingham and they’ll be there shortly.” You know that spiritual [song]—“Like a tree standing by the water, I will not be moved”? She would not be moved. And . . . I felt my voice go up another decibel and another and soon I was shouting, “Young woman, do you understand what you’re doing? You’re gonna get somebody . . . Do you understand you’re gonna get somebody killed?”  Diane Nash, of Fisk University, let John Seigenthaler know there was no turning back. And there’s a pause, and she said, “Sir, you should know, we all signed our last wills and testaments last night before they left. We know someone will be killed. But we cannot let violence overcome nonviolence.” That’s virtually a direct quote of the words that came out of that child’s mouth. Here I am, an official of the United States government, representing the president and the attorney general, talking to a student at Fisk University. And she, in a very quiet but strong way, gave me a lecture. |

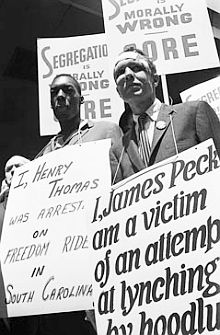

James Peck (right) and Hank Thomas march in a picket line outside the Port Authority Terminal in New York City.

Civil rights leaders at the national level, meanwhile, were spreading word of what had happened to the Freedom Riders in the south. In several U.S. cities, CORE chapters used the May 17th anniversary date of the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision to protest the violence in Alabama. They set up picket lines in front of bus terminals in cities such as Boston, Los Angeles, and New York. More than two thousand people came out for the New York City demonstration, with hundreds picketing the Port Authority terminals of the Greyhound and Trailways bus lines in protest over the segregated bus stations in the South. Some marchers carried signs that read, “segregation is morally wrong.” At least two of the Freedom Riders – Hank Thomas, who had been attacked in Anniston, and James Peck, who was beaten in Birmingham and was still bandaged – joined the demonstration in New York City. Peck carried a large placard that identified him as “a victim of an attempt at lynching by hoodlums,” and Thomas a sign that indicated he was arrested on a Freedom Ride in South Carolina. Following the New York demonstration, Peck and Thomas also answered questions and at a press conference held at the offices of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. Lillian Smith, a well-known author and southern liberal unafraid to criticize segregation and who worked to dismantle the Jim Crow laws, was also at the press conference. Other national figures began voicing their opinions as well. On Thursday morning, May 18th, the New York Times and other newspapers reported a story citing the Southern Baptist evangelist, Rev. Dr. Billy Graham, who said that the Southerners who had attacked and beaten the “Freedom Riders” should be prosecuted for their actions.

Rev. Shuttlesworth during “CBS Reports” TV show.

May 18,1961: Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, left, talks with several Freedom Riders waiting in the Birmingham bus station to go to Montgomery. AP photo.

May 20, 1961

Beatings in Montgomery

May 20, 1961: Jim Zwerg, one of the Freedom Riders beaten at Montgomery, Alabama bus terminal.

One of those on the arriving bus was Jim Zwerg, a 21-year-old white college from Beloit College in Wisconsin who became an exchange student at Fisk University an was also active in the Nashville sit-in movement. Zwerg was one of those selected for the “new troops” initiative for replacement Riders begun by Diane Nash and others. He was one of the group that left Birmingham earlier that day on May 20th. As Zwerg, stepped off the bus in Montgomery, someone shouted, “kill the nigger-loving son of a bitch!” With clubs and fists they attacked Zwerg brutally, beating him several times. He lost teeth in the beatings and was eventually hospitalized.

The mob also brutally attacked John Lewis, Bernard Lafayette, and William Barbee. Barbee was beaten unconscious and left on the sidewalk, suffering injuries that would later shorten his life. Three others escaped the violence by jumping over the retaining wall and running to the adjacent post office. Five black female Freedom Riders escaped in a cab driven by a black cab driver. Two white women were pulled from another cab and beaten by the mob.

May 20, 1961: Montgomery, AL mob member, later identified as a Klan leader, attacking news photographer.

Also on the scene that day in Montgomery to observe was Justice Department emissary John Seigenthaler, who was beaten as well. Seigenthaler, who saw the unfolding melee at the bus terminal from a distance, tried at one point from his car to help one of the female Freedom Riders being pursued in the street. But Seigenthaler was pulled from his car, beaten with a tire iron, his head fractured and left unconscious in the street.

In the aftermath, ambulances, manned by white attendants, refused to take the wounded to the hospital. Local blacks finally rescued the wounded, with some of the Freedom Riders eventually hospitalized.

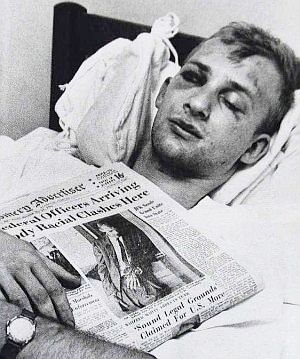

Freedom Rider Jim Swerg in his hospital bed after beating with a copy of the “Montgomery Advertiser” newspaper, with his bloody photo on its front page.

The Montgomery melee was front-page news the next day all across the country. The Montgomery Advertiser, for its part, ran a large photo of a beaten and bloody Jim Swerg on its front page (see photo at right).

In Washington, D.C., the melee was front-page news as well. Along with the bloody Zwerg photo, The Washington Post headlines that day also announced the actions of the federal government in response to the violence: “Kennedy Orders Marshals to Alabama After New Freedom-Rider Mobbing.”

Attorney General Robert Kennedy had been on the phone with Justice Department lawyer John Doar who was relaying a nearly blow-by-blow account to Kennedy of the mob violence as the fists and clubs began flying that day.

May 21, 1961: Washington Post runs “marshals-to-Alabama” front-page story on violence in Montgomery, along with photo of bloodied Freedom Rider, Jim Swerg

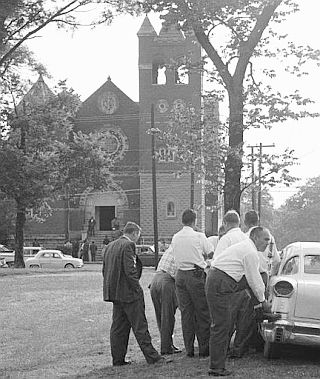

May 21, 1961: A contingent of Federal marshals gather to watch over civil rights activists and Freedom Riders coming to rally at the First Baptist Church in Montgomery. AP photo. |

Part of the 1,500 supporters who came out to learn about the Freedom Rides and hear from civil rights leaders – on what became a long night. Joseph Scherschel /Time Life |

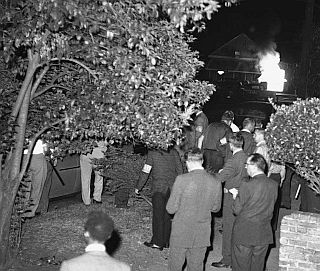

May 21, 1961: U.S. Marshals stand guard in front of Baptist Church as an automobile burns in the distance after being overturned by the mob. Photo, AP/Horace Cort |

May 21-22,1961: Rev. Ralph Abernathy & Rev. Martin Luther King during stand-off with white mob outside Abernathy’s Baptist Church in Montgomery, AL. King had been on the phone with Attorney General Robert Kennedy seeking help. Photo, Paul Schutzer/ Time Life. |

May 21-22, 1961: Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy on the phone at his Justice Dept office during the night of the church attack in Birmingham, Alabama. Bob Schutz/AP. |

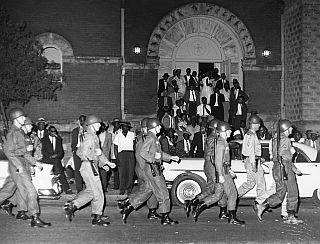

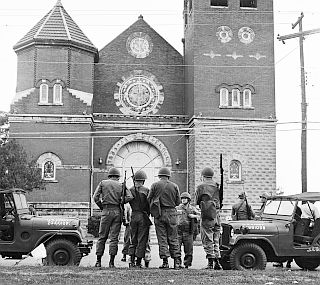

A detachment of National Guardsmen at the First Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama after martial law was declared. AP photo/Horace Cort. |

May 22, 1961: National Guard troops in front of the First Baptist Church, Montgomery, AL. AP/Horace Cort. |

May 21, 1961

Church Mob

In response to the violence, civil rights leaders called for a gathering of supporters in Montgomery for Sunday evening, May 21, 1961. They convened at Rev. Ralph Abernathy’s First Baptist Church and organized a program of hymns and speakers. About 1,500 community members attended along with civil rights leaders, including, Martin Luther King, Jim Farmer, Joseph Lowery, and Rev. Shuttlesworth.

The purpose of the gathering was to show support for the Freedom Rivers – of which more than a dozen attended. Diane Nash was also listed on the program, possibly to introduce the Freedom Riders. The First Baptist Church was located just a few blocks from the state capitol. Federal marshals, now on the scene in Montgomery, stood watch from a park near the church as evening services began on May 21st.

As those inside the church that night listened to testimonials about courage and commitment and sang hymns and freedom songs, a white mob began gathering outside. By nightfall the mob had grown larger, and had begun yelling racial epithets and hurling rocks at the church windows.

Inside, Martin Luther King Jr., told the crowd that Gov. Patterson was responsible for allowing the violence to happen. King also called for legislation to end desegregation and stop the violence. “We hear the familiar cry that morals cannot be legislated. This may be true, but behavior can be regulated,” King said. “The law may not be able make a man love me, but it can keep him from lynching me.”

During the evening, the mob grew, overturned a U.S. marshal’s car, and set a couple of small fires. The mob threatened to overwhelm the federal marshals who feared the church would be set on fire. According to one account of that evening by a U.S. Marshals historian, “a fiery projectile nearly burned the roof of the church.” At one point during the evening, some 75 marshals charged the angry mob and were pelted with rocks. The marshals were later bolstered by local and state police. Still, the mob persisted.

From inside the church that night, at around 3 a.m., King called Attorney General Robert Kennedy at the Justice Department for help. Kennedy then called Governor Patterson and also had his Deputy Attorney General, Byron White, later a Supreme Court Justice, meet with Patterson and his staff.

Back at the mob scene, meanwhile, it became obvious that the civilian federal marshals were overmatched by the mob’s larger numbers. It was at that point that Patterson, under federal pressure, declared martial law and authorized a National Guard battalion to disperse the crowd. The Alabama National Guard took control of the scene and the U.S. marshals were placed under Guard command.

One wire story of the church attack by United Press International that appeared in newspapers on Monday, May 22nd, reported: “Tear gas and fire hoses were needed to beat off the angry mob of about 200 whites who converged on the church [other accounts had that number much larger]. It took 100 U.S. Marshals and more than that number of city police and a National Guard contingent to hold back the rock-hurling, club-swinging mob.”

But it was early morning before the surrounding streets were secure enough for the Freedom Riders and their supporters to leave the church. Before dawn on May 22, 1961, the Guard moved the congregation out, using military trucks to transport some of the church attendees back to their communities,

Back in Washington, there had been early a.m. meetings at the Justice Department on the crisis, and Robert Kennedy, up all night, called President Kennedy at 7 a.m. to update him on what had happened.

On May 23, 1961, martial law was in place in Montgomery, Alabama, and national guard soldiers were present in front of the First Baptist Church and elsewhere in the city, including the Montgomery bus terminal.

Still, Patterson called the Freedom Riders “agitators” and said, “they were to blame for the race rioting because of their insistence on testing bus station racial barriers.”

The church attack and martial law were front-page news across the country. In Rome, Georgia, the News-Tribune story covering the church attack included reaction from state and local politicians, including some who blamed the Kennedys for encouraging “these people to come into the South to change traditions and the way of life.”

That story also quoted the Alabama Ku Klux Klan “grand wizard,” Robert Shelton, who said the klans of the nation would amalgamate in an effort to prevent further integration attempts in the South. He also added: “It is regrettable that the President of the United States would used the power of his office to condone the unlawful activities of these integrationist groups by attempting to enjoin the Alabama klans from aiding in the preservation of our laws and customs.” Shelton said that while the klan did not condone violence, it would “take all measures necessary” to preserve Alabama customs.

Back in Montgomery, on May 23, 1961, civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., Rev. Ralph Abernathy and James Farmer, and student leader John Lewis, held a news conference announcing that the Freedom Rides would continue.

The National Guard remained a presence in Montgomery following the mob activity at the First Baptist Church. Soldiers also lined the streets near the Montgomery bus terminals.

May 22, 1961: Alabama National Guardsman are also stationed at Montgomery bus station. AP photo. |

May 23, 1961: Civil rights leaders John Lewis, Martin Luther King Jr., Rev. Ralph Abernathy and James Farmer announcing that Freedom Rides would continue. |

May 24, 1961: National Guard troops line sidewalk at at bus station in Montgomery, AL as Freedom Riders plan to resume bus trips. Photo, AP / Horace Cort. |

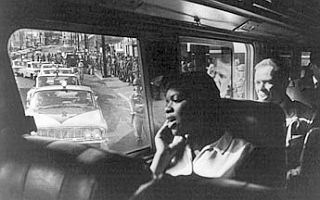

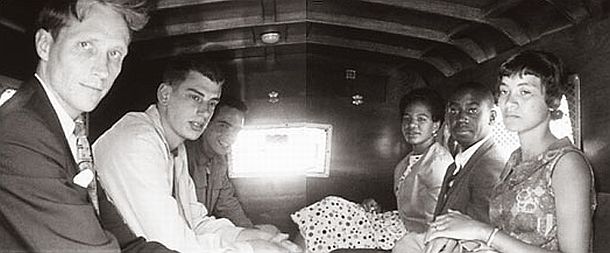

May 1961: Photo from inside bus departing from Mont-gomery for Jackson with police & Nat’l Guard escort. |

May 24, 1961: Wm.Sloan Coffin (glasses) and Yale group of Riders arriving in Montgomery, AL. Perry Aycock/AP |

May 24, 1961: Alabama National Guard protecting Freedom Ride bus at stop near Mississippi handover, at state border. |

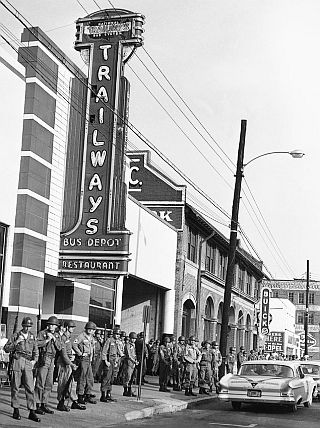

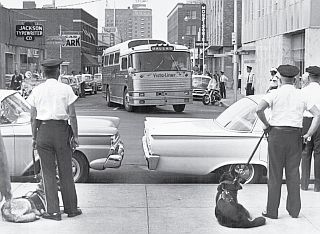

Jackson, Mississippi police line city streets near the bus station as Freedom Riders arrive there in May 1961. |

More Riders

On the morning of May 24, 1961, the Freedom Riders in Montgomery resumed their travels with two buses departing at different times for Jackson, Mississippi. The two buses carried 27 Freedom Riders between them and also some 20 members of the press. The buses were escorted by 16 highway patrol cars, each carrying three National Guardsmen and two highway patrolmen. A few national guardsmen were also on the buses. The ride from Montgomery to Jackson, a distance of about 140 miles, would take about six hours.

More Freedom Riders were also converging on Montgomery to fill more buses for additional trips into Mississippi. On the same day as the first buses departed for Jackson, for example, two white college students, David Fankhauser and David Myers, students at Central State College in Ohio, arrived in Montgomery. They were among those responding to the earlier call of Diane Nash seeking new recruits. On their arrival, these prospective riders and others would stay at local homes for a few days awaiting additional Freedom Riders sufficient to fill more buses.

Another bus arriving in Montgomery that afternoon from Atlanta brought a group of Riders from Connecticut, including four white college professors and three black students. Leading this group was white clergyman Rev. William S. Coffin, Chaplin at Yale University. Coffin, 35, and a WWII veteran, was also a member of President Kennedy’s Peace Corps Advisory Council. A day or so earlier on the Yale University campus, at a pre-Freedom Ride ally, Coffin had criticized southern ministers for not supporting the Rides. And in a Life magazine article a week or so later, Coffin also stated: “Many people in the South have criticized the Freedom Riders as ‘outsiders’ who want to stir up trouble. But if you’re an American and a Christian you can’t be an outsider on racial discrimination, whether practiced in the North or the South…”

Rev. Coffin also explained that by joining the Freedom Rides with his group “we hoped to dramatize the fact that this is not just a student movement. We felt that our being university educators might help encourage the sea of silent moderates in the South to raise their voices…”

Arriving at the Montgomery bus terminal on May 24th with Coffin that day were Dr. David E. Swift, Dr. John D. Maguire, and a contingent of Yale divinity students. The terminal was then patrolled by the National Guard. Still, a throng of angry whites had gathered there, but Sloan and others were able to make it to cars that carried them to meet with civil rights leaders at a local home. The next day, Coffin and his group were slated to board a bus for Jackson. However, while at the bus terminal that morning before departure, Coffin and others joined Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, and others at a terminal lunch counter, testing a “whites only” restriction. Most of this group, including Coffin, were arrested in the Montgomery terminal for “breach of peace and unlawful assembly,” and did not make the trip to Jackson. They were later released after posting $1,000 bond.

“Fill The Jails”

As Freedom Riders and civil rights leaders gathered at Ralph Abernathy’s home in Montgomery, including Martin Luther King, Fred Shuttlesworth, and student leaders, a new strategy was devised for the Freedom Rides heading into Mississippi. They decided that as more and more riders came to participate – then converging on Jackson, Mississippi where all incoming riders would likely be arrested – they would seek to “fill the jails” in Mississippi as part of the protest.

Back in Washington, meanwhile, the Kennedy Administration, was suffering some bad press overseas as new reports of the Freedom Ride violence spread around the globe. As one attempted counter to those reports, Robert F. Kennedy, on May 25, 1961, delivered a radio broadcast over Voice of America, defending America’s record on race relations, and adding, “there is no reason that in the near or the foreseeable future, a Negro could [not] become President of the United States.”

Back in Alabama, the two buses that had left Montgomery on May 24 were traveling on the road to Jackson with their convoy of police cars, National Guardsmen, and overhead helicopter. They were only making limited stops en route, during which National Guardsmen would array themselves around the bus in a protective manner. As they approached the Mississippi border, there would be a changing of the guard as the Mississippi Guard would take over from the Alabama Guard, and that transfer went smoothly. However, there had been one report of a phoned-in dynamite threat in Mississippi, so the Guardsmen at the state-line border exchange were especially attentive to their surroundings.

In Washington, Robert Kennedy had been negotiating with Mississippi officials over the safety of the Freedom Riders who were heading to Jackson. He struck a deal with Mississippi’s Democratic Senator, James O. Eastland, allowing the Riders to be jailed in exchange for their safety. Kennedy would not interfere in Mississippi’s affairs by sending in federal marshals as long as Eastland would guarantee there would be no mob violence. Kennedy explained that the Federal Government’s “primary interest was that they [Freedom Riders] weren’t beaten up.”

There were no incidents en route to Jackson, with the exception of some hecklers and a thrown bottle or two. The first two buses of Freedom Riders arrived in Jackson safely on May 24th, with no rabid white mobs awaiting them. As the Riders exited the buses and tested the whites-only or colored waiting areas, they were immediately ushered by police into a waiting paddy wagon which drove them to jail. The riders were typically charged with “breach of peace,” rather than breaking segregation laws. Freedom Riders responded with a “jail, no bail” strategy —part of the effort to fill the jails. Back in Montgomery, more Riders were preparing for the trip to Jackson. On May 28th, and in the days thereafter, additional buses with more Freedom Riders made the trip to Jackson.

Among those departing from Montgomery on May 28th for Jackson was Pauline Knight, a 20-year-old Tennessee State student, who would be arrested in Jackson and would later lead a brief hunger strike among female Rider-inmates. Describing the motivation that led Knight to participate in the Freedom Rides, she said: “It was like a wave or a wind, and you didn’t know where it was coming from but you knew you were supposed to be there. Nobody asked me, nobody told me.”

June 1961: A police paddy wagon in Jackson, Mississippi with arrested Freedom Riders aboard. Photo from “Breach of Peace” book, Eric Etheridge.

In fact, like Pauline Knight, the same kind of motivation was true for many who came to the Freedom Rides that summer – they just came, in the hundreds, unselfishly, out of personal conviction, finding it was the right thing to do. It was a spontaneous movement of individuals, each coming from separate locations, but each making a similar decision to become personally involved. It was a simple but powerful statement of democratic action – one that augured well for America’s future, and a proud moment for all of its citizens.

Back in Washington, meanwhile, on May 29th, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy formally petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission to adopt “stringent regulations” prohibiting segregation in interstate bus travel. The proposed order would not be issued for several months, but the process was set in motion. Kennedy was also trying to dissuade the Freedom Riders from continuing their protest, asking for “cooling off” period that went nowhere. In fact, if anything, the movement only grew larger in the months ahead as individuals all around the country responded.

|

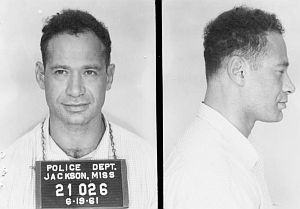

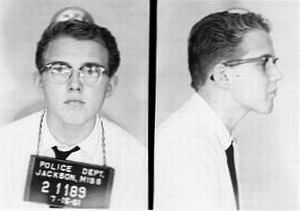

Ray Cooper  Mug shot of Ray Cooper, 19, arrested in Jackson, MS. …Gathering in New Orleans, we were getting to know one another, bonding to find the courage to act together. There was a wave of volunteers and we had the moral advantage. I could not have continued past New Orleans if there had been a meager turn out. Strength in numbers. Was I frightened? Yes. But like the others I was calm and focused. I was nineteen and was about to do something meaningful for the first time in my life. I had resolved not to participate with the U.S. military adventure in Vietnam. The battle at home was my choice. I was testing myself, challenging my country to actually “free the slaves” not just talk about it… I had read about Gandhi in high school.“I had read about Gandhi in high school. He stood against the British Empire. People listened to him and won. I admired that. . . .” He stood against the British Empire. People listened to him and won. I admired that. Martin Luther King Jr. quoted him. I respected that. I believed that nonviolent resistance would also work in America where people professed belief in democracy. It was a gamble but was a rather “strong hand”… [Ray Cooper later boarded his Greyhound Bus in New Orleans, headed for Jackson, Mississippi]. …We arrived in Jackson in [July]. Police and their vans surrounded the terminal. They watched passively as we walked into the whites only waiting room. Once inside we sat on available benches together with arms locked. The police ordered us out. We declined. Threatened with arrest we went limp and were dragged from the Greyhound station by our feet and were loaded into paddy wagons. . . . Arrested and booked for unlawful assembly, we entered the jails of Jackson City and County. We were, of course, segregated by race and sex. Our fear was not of police mistreatment, but of the uncertainty of being housed with criminal prisoners. At no point during the summer did this occur. The standard length of incarceration was forty-five days, first in Jackson and ultimately at Parchman . . . All summer long the buses kept arriving with more Freedom Riders… _____________________________ |

Headline from ‘The Morning Herald’ newspaper of Hagerstown, MD, May 25, 1961 announcing jailing of Freedom Riders in Mississippi with photo of Riders being loaded into paddy wagon.

Mississippi’s governor, meanwhile, Ross Barnett, had the Freedom Riders in his sights, and set out “to teach ‘em a lesson” and “break the back” of their movement. By doing “real time in a real prison” like Parchman, Barnett believed his Mississippi jailers would give the Riders an education they would remember, helping to end the Freedom Rides. But Barnett’s jailers would underestimate the resolve and ingenuity of their charges. Among other measures to maintain their spirits while jailed, the Riders sang freedom and folk songs – among them, “Buses Are A’Comin, Oh Yeah,” which surely made their jailers boil. When the Riders refused to stop singing, prison officials took away their mattresses and toothbrushes. But the Riders kept singing, and also devised other strategies to survive their jail time. Most would endure a sentence of about 45 days.

PBS “Freedom Riders” map showing routes traveled as of July 1961, when some 367 Riders had participated.

Freedom Riders would also test train and plane routes and their related facilities — waiting areas, restrooms, and restaurants — at train stations and airports. Riders also went to Arkansas, Florida and Texas; some came from New York and Los Angeles. In fact, they came from all regions of the U.S., and some from Canada as well. (see PBS Freedom Riders website for full list of rides, riders, and routes traveled).

Media Coverage

Newsweek’s June 5, 1961 featured three of the contending major players in the Freedom Rider controversy that continued throughout the summer. |

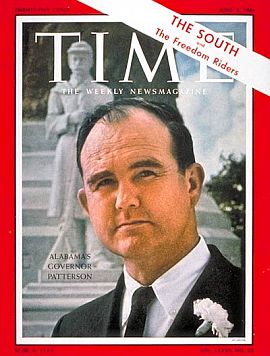

By early June, the Freedom Riders story was front-page national news almost everywhere. Magazines such as Time and Newsweek had cover stories devoted to the latest developments. Life magazine in early June also chose the Freedom Riders and the unrest in Montgomery as its “story of the week.”

Time magazine featured the Freedom Riders as its cover story, using a cover photo of 39 year-old Governor John Patterson and focusing on the governor’s segregationist career, the incidents that had occurred in his state, and the fight between he and Robert Kennedy over enforcing the law.

Newsweek also had a photo of Patterson on its cover that week, along with those of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy – featuring the three contending players in that week’s news with quotes from each displayed with their photos. “We stand for human Liberty,” ran beside RFK’s photo. “We must be prepared to suffer…even die,” was attributed to Rev. King. And in the third frame, Gov. Patterson was quoted saying: “The Federal government encourages these agitators.”

Life magazine ran several pages of photos and narrative for its story of the week – “The Ride for Rights: Negroes Go by Bus Though the South Asking for Trouble and Getting It. Among Life’s photos in that issue was a sequence from the siege of the First Baptist Church in Montgomery.

More news reporters and photographers were drawn to the story by this time as well. A number of the media had already witnessed the early mob violence visited on the Freedom Riders in Montgomery. More reporters joined on the bus rides in late May 1961 during the National Guard escort from Alabama to Mississippi and others came to Jackson, Mississippi as the “breach of peace” arrests were made throughout that summer. As a result, Freedom Rider stories continued to appear in the news media through the summer and fall of 1961. The media coverage of the Rides kept the issue on the nation’s front burner. Yet it was the rising up of individuals all across the country that kept the Rides going – much to the dismay of the Kennedy Administration which tried to dissuade the Riders from continuing.

By November 1, 1961, the ICC rule that Robert Kennedy had initiated began to be enforced. With the new rule, passengers were permitted to sit wherever they pleased on interstate buses and trains and related facilities. All the “white” and “colored” signs came down at all terminals. There would be no more segregated drinking fountains, toilets, or waiting rooms. Lunch counters would serve all customers, regardless of race. However, there were still pockets of resistance in some locations. Black riders encountered stiff resistance in December 1961 when they attempted to desegregate a white waiting room in Albany, Georgia. Other locations also offered resistance. But eventually, the rule took hold everywhere, and segregated interstate travel and accommodation ended.

The Legacy

The Freedom Rides and Freedom Riders of 1961 provided an important boost to the civil rights movement. The Rides brought new momentum, new energy, and a broadening constituency to the movement. The grass roots nature of its participants also empowered the cause in a new way, directly influencing, and helping inspire, other activities that followed – from the March on Washington in August 1963 and the Freedom Summer movement in Mississippi in 1964, to landmark federal legislation culminating in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the voting Rights Act of 1965.

May 1961: Scene from Montgomery, Alabama after National Guard arrived to protect Freedom Riders from local mobs. / Bruce Davidson

And for the nation as a whole – the nation watching the horrors on television and reading the news accounts of what was happening, and seeing more and more people step forward willing to risk bodily harm and/or imprisonment – the Freedom Riders helped change minds and stiffen the national backbone for confronting Jim Crow. As the PBS Freedom Riders website has put it: “The courage and stoicism of the Freedom Riders, in the face of the most vicious hatred and racism and physical beatings, left a deep impression on the nation and the world.”

The Freedom Rides also became established in popular literature and American history practically from the beginning. In 1962, James Peck, a veteran CORE member and Freedom Rider who was badly beaten in Anniston and Birmingham, published his account of the Rides in a book first published by Simon and Schuster, titled Freedom Ride. Later editions of Peck’s book included a forward by African American author James Baldwin. Other books on the Freedom Rides followed in the 1980s and 1990s, some of which are listed in “Sources” below, as well as more comprehensive books on the overall civil rights movement, which typically incorporate special sections on the Freedom Rides.

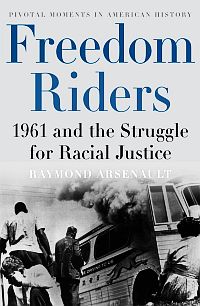

In recent years, the Freedom Rides have received more in-depth treatment in volumes such as the January 2006 book by Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders: 1961 and The Struggle for Racial Justice, published by Oxford University Press. This volume, at 704 pages, is regarded by many as the definitive treatment of the 1961 Freedom Rides and their impact. One review of the book appearing in the New York Times Book Review by Eric Foner notes, for example:

“Drawing on personal papers, F.B.I. files, and interviews with more than 200 participants in the rides, Arsenault brings vividly to life a defining moment in modern American history…. Rescues from obscurity the men and women who, at great personal risk, rode public buses into the South in order to challenge segregation in interstate travel…. Relates the story of the first Freedom Ride and the more than 60 that followed in dramatic, often moving detail.”

Aresnault’s book became a primary source for a the PBS/American Experience documentary, Freedom Riders – an excellent two-hour show that first aired in mid-May 2011 and has since won numerous awards. 2011 was also the 50th anniversary year of the Freedom Rides, during which a number of other books, short films, museum specials, and other commemorations were produced – including a special May 2011 edition of The Oprah Winfrey Show. A number of these are also referenced in “Sources” below, many with links. However, one volume that came out in 2008 deserves special mention for the imagery and personal stories it brought forth, providing a whole new perspective on the Freedom Rides.

Eric Etheridge discovered the archive of Freedom Rider mug shots in 2003.

In 2003, Eric Etheridge, a native of Carthage, Mississippi, had lived and worked in New York City. He had done some work for Rolling Stone and Harper’s, but was then looking for a new photography project.

During a visit to Jackson, Mississippi in 2003 to see his parents, he was reminded that a lawsuit had forced the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission – an agency created in 1956 to resist desegregation – to open its archives. The agency files, put online in 2002, included more than 320 police mug shots of Freedom Riders arrested for “breach of peace” in Jackson, Mississippi. The photos cover those incarcerated from late May to mid-September 1961.

The trove of photos, Eteridge concluded, was a pot of gold, and important history that should have wider circulation. “The police camera caught something special,” Etheridge would later say. The segregationist Sovereignty Commission had unintentionally created and preserved an important visual record of the Freedom Rides and civil rights history.

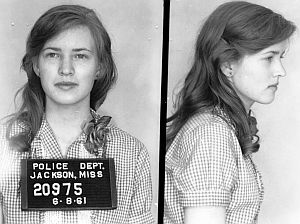

Eric Etheridge’s 2008 book, using Freedom Rider mug shots for “then- and-now” profiles of 80 Riders. Click for book.

The result of Eteridge’s sleuthing was the book, Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders, published in May 2008. It features 80 of the Freedom Riders, each shown in their 1961 mug shots alongside a more current photo that Etheridge took, plus interviews he did with the activists reflecting on their Freedom Ride experiences. More than two dozen of the riders Etheridge interviewed went on to become teachers or professors. There are also eight ministers as well as lawyers, Peace Corps workers, journalists and politicians.

Of the 320 or so Freedom Riders arrested in Mississippi, nearly 75 percent were between 18 and 30 years old. About half were black; a quarter, women. And as many who have examined these photos have concluded, the mug-shot expressions displayed by the riders in that famous summer of 1961 not only offer a look at the collective face of democracy in action, but also a measure of each Rider’s composure and determination at the time – and in some cases, their defiance, pride, vulnerability and/or fear as well. Yet above all, at least in the collective, there is an overwhelming optimism that seems to come through – and for the observer, faith in one’s “fellow man.”

A small cross-section of the 328 Freedom Riders who were arrested in Mississippi during the summer of 1961 – most of whom were processed in Jackson, MS and likely served time in Parchman State Prison for their “crime.”

The Mississippi Freedom Rider mug shots helped bring a new dimension to the Freedom Rider story, and many are now circulating on the web with personal histories attached, including “where-are-they-now” details. This visual record also helped enliven the 2011 PBS documentary mentioned earlier, and in some cases the photos have also been used on more recent book covers, magazine specials, websites, and DVDs exploring Freedom Rider history. They have also been used in special exhibits and in displays at some museums. A dozen or so are also offered below in “Sources,” only as a sampling, with very brief sketches.

For additional civil rights history at this website please visit “Civil Rights Stories,” a topics page, which includes thumbnail sketches and links to 14 additional story choices. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 24 June 2014

Last Update: 18 July 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Buses Are A’Comin’- Freedom Riders: 1961,”

PopHistoryDig.com, June 24, 2014.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders: 1961 and The Struggle for Racial Justice, New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

WGBH, “Freedom Riders,” PBS/American Experience, Film & Website, PBS.org.

“Democracy in Action: A Study Guide to Accompany the Film, Freedom Riders,” American Experience/PBS/WGBH, PBS.org, 2011.

Terry Gross, “Get On the Bus: The Freedom Riders of 1961,” Fresh Air, WHYY/NPR, January 12, 2006.

“Freedom Rides,” Encyclopedia of Alabama.

“1961: Freedom Rides (May-Nov),” Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement, crmvet.org.

“Freedom Riders,” Wikipedia.org.

Elsie Carper, “Pilgrimage Off on Racial Test,” Washington Post, May 5, 1961, p. B-4.

United Press International ( Rock Hill, S.C., May 10), “Biracial Unit Tells of Beating in South,” New York Times, May 11, 1961.

“Newsfilm Clip of a Burned out Greyhound Bus and Injured Freedom Riders in the Hospital in Anniston, Alabama,” WSB-TV (Atlanta, GA), May 14, 1961, Civil Rights Digital Library.

Associated Press (Anniston, Ala., May 15), “Bi-Racial Buses Attacked, Riders Beaten in Alabama; Alabama Whites Fire Bi-Racial Bus, New York Times, May 15, 1961, p. 1.

“Darkest Alabama,” Editorial, Washington Post, May 16, 1961.

United Press International (UPI), “Bi-Racial Group Cancels Bus Trip; Alabama Rejects Appeal by Robert Kennedy for Guard; Bus Drivers Balk at Bi-racial Trip; State Inspector Aids Passengers in Bus Burning,” New York Times, May 16, 1961.

“Pickets March Here,” New York Times, May 18, 1961.

Jack Gould, “TV: ‘C.B.S. Reports’ Turns Camera on Birmingham; Negroes and Whites State Their Views; Program Sheds Light on Conflicting Forces,” New York Times, May 19, 1961, Business, p. 63.

Associated Press, “Judge Issues Writ; Alabama Judge Bars Attempts At ‘Freedom Rides’ in the State,” New York Times, May 20, 1961, p. 1.

Associated Press (Birmingham, Ala., May 19), “Crowd at Bus Station,” New York Times, May 20, 1961.

“SNCC Wires President Kennedy,” The Student Voice (The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC), Atlanta, Georgia, April-May1961, p. 1.

“Freedom Rides,1961,” The Student Voice (The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC), Atlanta, Georgia, April-May1961, p. 3.

Associated Press (Montgomery, Ala, May 20), “Freedom Riders Attacked by Whites in Montgomery; President’s Aide Hurt by Rioters; Battle Rages for 2 Hours as Mobs Chase and Beat Anti-Segregation Group,” New York Times, May 21, 1961, p.1.

“Negroes, Whites Try to Renew Freedom Ride,” Los Angeles Times, May 20, 1961, p. 3.

U.S. Sends 400 Officers to Alabama After Riot,” Los Angeles Times, May 21, 1961, p. F1-F2

Montgomery Baptist Church Program, “The Montgomery Improvement Association Salutes The Freedom Riders,” May 21, 1961, Montgomery, Alabama.

Anthony Lewis, “400 U.S. Marshals Sent to Alabama as Montgomery Bus Riots Hurt 20; President Bids State Keep Order; Force Due Today Agents to Bear Arms — Injunction Sought Against the Klan,” New York Times, Sunday, May 21, 1961, p. 1.

“Kennedy Orders Marshals to Alabama After New Freedom-Rider Mobbing,” Washington Post, May 21, 1961, p. 1.

“Russians Scornful; Refer to Alabama Violence as ‘Bestial’ U.S. Custom,” New York Times, May 22, 1961.

“Martial Law Declared in Alabama’s Capital; National Guard Troops Put Down New Riot; Wild Mob Trying to Overthrow U.S. Marshals; Scattered Troops Quell New Riots in Alabama’s Capital,” Los Angeles Times, May 22, 1961, pp. 1-3.

Susan Herrmann, “Southland Coed Caught in Rioting; Coed’s Story,” Los Angeles Times, May 22, 1961, p. 1

UPI, “Patterson Declares Martial Law As Alabama Negro Church is Attacked; New Violence Explodes in Montgomery Sunday,” Rome News-Journal (Rome, Georgia), May 22, 1961, pp. 1-2.

Dave Turk, “An Emergency Call to Montgomery,” U.S. Marshals Service.

Alison Shay, “On This Day: First Baptist Church Under Siege,” This Day in Civil Rights History, May 21, 2012.

“27 on Freedom Busses Arrested in Mississippi,” Los Angeles Times, May 25, 1961, p. 1-3.

“Days of Violence in the South,” Newsweek, May 29, 1961, p. 22.

“‘Freedom Riders’ – and Mob Violence,” U.S. News & World Report, May 29, 1961, p. 6.

“The South: Crisis in Civil Rights,” Time, Friday, June 2, 1961, pp. 14-15.

“The Ride for Rights: Negroes Go by Bus Though the South, Asking for Trouble and Getting It,” Life, June 2, 1961, pp. 46-53

William Sloan Coffin (as told to Life correspondent Ronald Baily) “Why Yale Chaplin Rode: Christians Can’t Be Outside,” Life, June 2, 1961, pp. 54-55.

“Freedom Riders Force a Test… State Laws or U.S. Law in Segregated South?,” Newsweek, June 5, 1961, pp. 18-20.

“A New Breed – The Militant Negro in the South,” Newsweek, June 5, 1961, p. 21.

“How the World Press Viewed the Days of Tension,” Newsweek, June 5, 1961, p.22.

“Is the South Headed for A Race War?,” U.S. News & World Report, June 5, 1961, p. 43.

“Ten Riders Hit City; 8 Jailed,” State Times (Jackson, MS), July 30, 1961.

James Clayton, “ICC Forbids Bus Station Segregation,” Washington Post, September 23, 1961, p. A-1.

Val Adams, “Howard K. Smith and CBS End Tie,” New York Times, October 31, 1961.

James Kates, “Kicking Nixon: Howard K. Smith and the Commentator’s Imperative,” ARNet, March 6, 2014.

Sid Moody, Associated Press, “Freedom Rides Brought More than Violence,” February 8, 1962.

James Peck, Freedom Ride, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1962.

Taylor Branch, Parting The Waters: America In The King Years 1954-1963, New York, Simon & Schuster; 1988.

Glenn T. Eskew, But for Birmingham: The Local and the National Movements in the Civil Rights Struggle, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

David Halberstam, The Children, New York: Random House, March 1998, 783 pp.

John Lewis, Walking With the Wind, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998.

Richard Lentz, Symbols, The News Magazines, and Martin Luther King, LSU Press, March 1, 1999, 392 pp.

Jon Wiener, “Southern Explosure,” The Nation, June 11, 2001.

David J. Mussatt, “Journey for Justice: A Religious Analysis of the Ethics of the 1961 Albany Freedom Ride,” Ph.D. Thesis, Temple University, 2001

David Niven, The Politics of Injustice: The Kennedys, The Freedom Rides, and The Electoral Consequences of a Moral Compromise, Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2003.

PBS-WGBH, “1961: The Freedom Rides,” Eyes on The Prize/American Experience, 2005 (page created, August 23, 2006).

Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff, The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation, New York: First Vintage Books, 2006.

Joan Mulholland, “Why We Became Freedom Riders,” Washington Post, May 17, 2007.

Dale Anderson, Freedom Rides: Campaign for Equality, Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2007.

“More Freedom,” PictureYear.Blogspot.com, Thursday, May 8, 2008.

Jennifer Balderama, Arts Beat, “Disturbing the Peace,” New York Times, July 3, 2008.

Bob Minzesheimer, Books, “Freedom Riders Again Ride in ‘Breach of Peace;’ They Put Up a Segregation Fight in 1961,” USA Today, Tuesday, July 15, 2008, p. 3-D.

Eric Etheridge, Breach of Peace (website), 2008-2010.

Mississippi Department of Archives & History, Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, Files, 1956–1973.

“Tennessee A & I Freedom Riders 14,” Tenn-essee State University, 2008.

Thomas Forrest, “Freedom Riders / Free At Last: 47 Years Later It’s A Different Story,” Jackson Free Press (Jackson,MS), July 30, 2008.

Marian Smith Holmes, “The Freedom Riders, Then and Now,” Smithsonian Magazine, February 2009.

“The Freedom Riders: New Documentary Recounts Historic 1961 Effort to Challenge Segregated Bus System in the Deep South,” Democracy Now, February 1, 2010.

Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, Oxford University Press, 1st abridged edition, March 2010 (and companion book to the 2011 PBS documentary).

“Memories of a Freedom Rider, by Ray Cooper,” SeattleInBlackandWhite.org.

“Freedom Rides: Recollections by David Fankhauser,” U.C. Clermont College, Batavia, Ohio.

David Fankhauser, “I Was a Teenage Freedom Rider: Ride for Freedom; Ride for Justice 50 Years Later,” Lecture & Slide Show, Presented to UC Blue Ash College, October 24, 2013.

Dr. Fankhauser is Professor of Biology and Chemistry, UC Clermont College, YouTube. com.

Michael T. Martin, “‘Buses Are a Comin’. Oh Yeah!’: Stanley Nelson on Freedom Riders,”

Black Camera, Volume 3, Number 1, Winter 2011, pp. 96-122.

Jess Bidgood, “From Lowell to Jackson, One Freedom Rider’s Story,” WGBH.org, April 27, 2011.

“50 Years Ago Today Freedom Rides Began,” Birmingham Public Library, Wednesday, May 4, 2011.

“Oprah Honors Freedom Riders,” Oprah .com, May 4, 2011.

Colleen O’Connor, “50 Years Ago, Freedom Riders Blazed a Trail for Civil Rights,” The Denver Post, May 6, 2011.

Freedom Riders Photo Gallery, Commercial Appeal.com, May 20, 2011.

“May 20, 1961: Riders in the Storm,” YouTube.com, Posted by RFK Center for Justice and Human Rights, Uploaded, May 24, 2011,

“May 1961: Freedom Rides,” The ’60s at 50, May 24, 2011.

“Photos: The 50th Anniversary of the Freedom Riders,” DenverPost.com, Posted May 31, 2011.

Amy Lifson, “Freedom Riders,” Humanities, May/June 2011, Vol. 32, No. 3.

Photo Gallery, “50 years After the Freedom Riders,” WashingtonPost.com, 2011.

“Mug Shot: A Freedom Rider’s Arrest Photo,” Yale Alumni Magazine, Nov/Dec 2011.

EJ Dickson, “Memories of a Movement: Oberlin Alumni Reflect on Their Time in the Civil Rights Movement of the Early 1960s,” Oberlin Alumni Magazine, Summer 2012, Vol. 107, No. 3.

“The Road to Civil Rights: Freedom Riders,” Federal Highway Administration, Updated, October 17, 2013.

“Martin Luther King Jr. and the Freedom Riders: Rare and Classic Photos,” Life.Time .com.

Freedom Rides of 1961, from “History & Timeline of the Southern Freedom Movement, 1951-1968,” Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement.

Taylor Street Films, An Ordinary Hero: The True Story of Joan Trumpauer Mulholland, (documentary film; 91 minutes), February 2013.

“Civil Rights in America: Connections to A Movement,” USA Today.

Civil Rights Series, “A Movement Emerges in Nashville,” The Tennessean.

“Freedom Riders(film),” Wikipedia.org.

Olga Hajishengallis, “Portraits of Civil Rights Pioneers,” USA Today, February 6, 2014.

“Singleton Freedom Riders,” Website of Helen & Bob Singleton (with video), 2014.

“Freedom Riders,” PBS Film, Online Viewing, PBS.org.

Appendix: “Roster of Freedom Riders”.

Rhonda Colvin, “‘We Were Soldiers’: The Flesh and Blood Behind the New Civil Rights Monument,” WashingtonPost.com, January 15, 2017.

Civil Rights History

Thomas Rose, Black Leaders, Then and Now: A Personal History of Students Who Led the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960’s – And What Happened to Them (Julian Bond, Senator, Atlanta, Georgia; Marion Barry, Mayor, Washington, DC; Charlayne Hunter-Gault, Television Correspondent, MacNeil-Lehrer News Hour), Youth Project, Garrett Park, MD: Distributed by Garrett Park Press, 1984.

David J. Garrow, Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, New York: W. Morrow, 1986.

Gary A. Donaldson, The Second Recon-struction: A History of the Modern Civil Rights Movement, Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing, 2000.

Bobby M. Wilson, Race and Place in Birm-ingham: The Civil Rights and Neighborhood Movements, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2000.

S. Jonathan Bass, Blessed are the Peace-makers: Martin Luther King, Jr., Eight White Religious Leaders, and the “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001.

John Blake, Children of the Movement: The Sons and Daughters of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Elijah Muhammad, George Wallace, Andrew Young, Julian Bond, Stokely Carmichael, Bob Moses, James Chaney, Elaine Brown, and Others Reveal How the Civil Rights Movement Tested and Transformed Their Families, Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2004.

Frederic O. Sargent, The Civil Rights Revolution: Events and Leaders, 1955-1968, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2004.

Juan Williams, My Soul Looks Back in Wonder: Voices of the Civil Rights Experience, New York: AARP/Sterling, 2004.

Gilbert Jonas, Freedom’s Sword: The NAACP and the Struggle Against Racism in America, 1909-1969, New York: Routledge, 2005.

Vanessa Murphree, The Selling of Civil Rights: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Use of Public Relations, New York: Routledge, 2006.

Linda Barrett Osborne, Women of the Civil Rights Movement, San Francisco: Pome-granate; Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 2006.

Renee C. Romano, ed., The Civil Rights Movement in American Memory, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2006.

___________________________________

![Ellen Lee Ziskind was volunteering at the CORE offices in NY City the summer before her last year at Columbia University. She heard first-hand accounts from Freedom Riders who’d been beaten and jailed. “I think they kind of took my breath away,” she would later recall. “...[I]t was kind of like a story from another country. And I was so... struck by, swept away by their working to have a democracy.” She later volunteered, rode a bus to Jackson and served six weeks in Parchman.](/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/mugs-ellen-lee-ziskind-300.jpg)