The battle began when Shell sought to dispose of a gigantic, decommissioned North Sea oil storage rig named the Brent Spar. Shell proposed to dump the rig into the North Atlantic Ocean.

Greenpeace by the mid-1990s was a well-known environmental group globally – known especially for their often heroic direct-action protests at sea. In 1985, their Rainbow Warrior boat, scheduled to protest nuclear weapons testing in the Pacific Ocean, was blown up at a dock in New Zealand by French agents, killing one activist. That incident galvanized public support for the group, and their membership climbed for a time, only to ebb away a bit in the early 1990s. The Brent Spar battle, however, would spark renewed interest in the group and their environmental campaigns.

The book cover at right depicts a scene from the North Sea in June 1995 as Greenpeace activists in a motorized rubber raft were attempting to board the Brent Spar facility amid water-cannon fire from nearby Shell vessels attempting to discourage the activists from approaching and boarding the Spar.

What follows below is a re-telling of the Greenpeace/Brent Spar battle and the role the activists and their organization played in that intervention – not only at sea, but also in negotiations and other activity throughout Europe at the time. Included, as well, is some review of related offshore oil/ environment issues in the North Sea and other regions as of October 2019.

* * * * * *

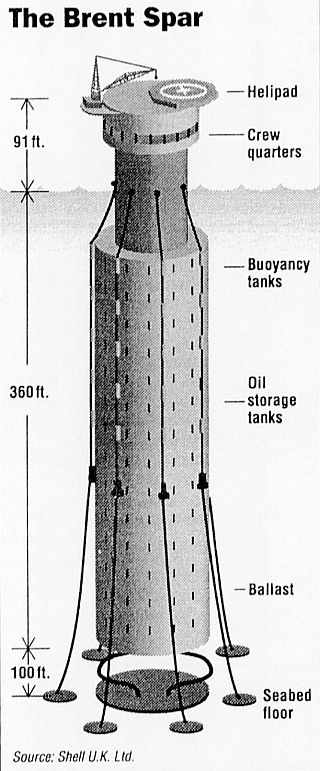

Graphic describing the Brent Spar oil storage structure.

North Sea Oil

In the early 1970s, Royal Dutch Shell, and its then project partner, Esso, a predecessor of ExxonMobil, were faced with an oil storage problem for their North Sea oil operations – the North Sea then, and still, a major realm of offshore oil production.

The oil companies needed a facility on the water into which they could pump and store their Brent Field crude oil while awaiting collection.

At the time, there were essentially two storage options: using a permanently-moored oil tanker, or building a new kind of huge, cylindrically-shaped, floating oil storage unit called a “spar.”

The name is taken from the old “spar buoy” used in navigation, traditionally a long piece of colorfully-painted timber anchored at one end to sit upright in the water. However, in this case the spar would be an industrial behemoth – a gigantic, floating oil tank, which stood on its end, would be equivalent to a 40-story structure, tethered with massive chains to six 1,000-ton concrete blocks — a structure of more than 460 feet in total length, with about 100 feet of that visible above the water’s surface (see graphic at left).

The storage tank section would have a capacity of 300,000 barrels of crude oil. The Brent Spar, it turns out, would be the first of other kinds of spars used in the industry, and particularly, production spars, which have become most prevalent in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico. Spars are also found in offshore Malaysia and Norway.

Back at Shell headquarters in the early 1990s, internal analysis showed the moored tanker option to be cheaper than the floating “spar.” Esso, in fact, favored the tanker option. But Shell as operator had the final say, and it wanted to use the spar – Brent Spar, as it would be called. Shell also stated that it favored the spar option, in part, because the risk of polluting the sea with the tanker option would be “significantly higher.”

The very top of the Brent Spar oil storage unit during its operation, showing helipad and operating level, with more than 450 feet of its below-sea storage tanks not shown.

The Brent Spar continued to operate for nearly 15 years, until September 1991. During that time a number of large tanker ships – such as the Esso Warwickshire, shown in the photo below — would come to load North Sea oil from the facility.

In the intervening years, however, a pipeline was built, relieving Shell and Esso of the need for the Brent Spar storage unit. So, by the early 1990s, Shell was faced with a decision about what to do with the Spar, as it had outlived its usefulness but could not remain in place since it would pose a danger to shipping and over time would also break apart.

Photo showing large oil tanker, the “Esso Warwickshire," taking on oil from the Brent Spar storage unit during its working years, likely sometime in the late 1970s or early 1980s.

Dump or Dismantle?

Although a study of 13 different options for the Spar’s disposal ensued over a 30-month period, there were essentially two choices: dumping the rig at sea or dismantling it on land. The studies that Shell commissioned showed that sea dumping was the cheapest route, while dismantling the rig on shore would be more expensive. One estimate found that sinking the Spar would cost $19 million, while dismantling it on land would cost $70 million. The dismantling-on-land option had potential environmental and worker exposure costs. The ocean dumping option would mean that the Brent Spar would be towed more than 100 miles out into the North Atlantic Ocean and sunk in a very deep trench there where the environmental effects were projected to be minor. Shell acknowledged there were toxic and radioactive materials aboard the vessel — a small amount of radioactive waste, small quantities of cadmium and mercury, and 53 tons of oil and oily wax. The scientists and studies commissioned by Shell found that these materials would create no major environmental or health problems. Britain’s National Environment Research Council also found the sea disposal acceptable, noting that “the direct impact on the environment would be small, since at these depths animal life is sparse and only loosely connected to the food chain.” Still, it would be the first time that an offshore oil facility of this size and kind would be disposed of at sea.

Map shows the approximate locations of the Brent Spar, and its proposed 1995 dumping location, in the North Feni Ridge region, out in the north Atlantic Ocean, off the northwest coast of Scotland.

By February 1995, the disposal had the approval of Shell’s board and the UK government, which said at the time the disposal was fully in line with the 1991 Oslo and Paris Convention (OSPAR) of internationally-agreed guidelines for the disposal of offshore installations at sea. So the dumping was set: the rig would be towed out into the Atlantic Ocean, 150 miles off the northwest coast of Scotland. There it would be sunk in more than 6,000 feet of water.

Greenpeace Action

But two months later, in April 1995, the Brent Spar was about to have some unwelcome visitors. On the evening of April 29th, 1995, just before sunset, a group of Greenpeace activists, in an old fishing vessel named the Moby Dick, set sail from the Shetland Islands. Their destination was the Brent Spar, 118 miles and fifteen hours away. And their objective was to board and occupy the Spar in protest of its proposed dumping at sea.

1995. Greenpeace activists approaching the base of the Brent Spar, would scale the structure to the helicopter pad where they would begin their occupation and protest.

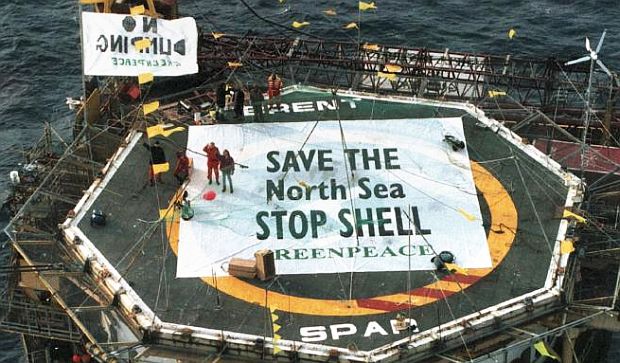

Arriving near the Brent Spar by mid-day on April 30th, the Moby Dick rendezvoused with another contingent of German Greenpeace activists who had come by chartered vessel. Rubber rafts were shortly put into the water. Minutes later, four of the activists had reached the giant Brent Spar structure, scaling its tower and unfurling a banner at the top of the Spar on its flat helicopter-pad. The banner – clearly legible from fly-overs above – read: “Save the North Sea. Stop Shell.” The activists, meanwhile, had come to stay, bringing initial quantities of food and setting up shop in the Spar’s living quarters and galley, also establishing a communications capability.

The Greenpeace action at the Brent Spar was no spur-of-the-moment crusade. In fact, Greenpeace had heard about Shell’s plan to scuttle the rig more than a year earlier, and in the summer of 1994 had set out their own study to look into the decommissioning options, finding that the dump at sea would be about four times cheaper for Shell than to dismantle it on land. They soon decided to take on the fight – and planning to get media attention in the battle was at the top of their list. In fact, they made sure to acquire satellite communications and video equipment in advance so their people would be able to transmit televised pictures during the protest. So once the Greenpeace activists had boarded the Brent Spar on April 30, 1995, the Greenpeace media plan would begin.

Greenpeace activists atop the Brent Spar rig in the North Sea, April 1995, with protest banners – one reading “Save The North Sea: Stop Shell’ – opposing Shell’s proposed dumping & disposal of the rig in the north Atlantic Ocean.

On the Moby Dick, meanwhile, which also carried some news reporters, Greenpeace organizer, Tim Birch, announced that “Greenpeace will remain on the Brent Spar until the UK government or Shell come to their senses and revoke the decision to dump it.” Back in London, Greenpeace released a report to the media entitled, No Ground for Dumping: The Decommissioning and Abandonment of Offshore Oil and Gas Platforms. Greenpeace was using the Brent Spar disposal to raise larger issues for the region: the North Sea ministers would soon meet in Denmark to discuss solutions to toxic environmental problems affecting the North Sea. Britain had been a laggard in this effort, due in part to its highly lucrative North Sea oil revenues.

During early and mid-May 1995, the activist numbers on the rig grew to 14 along with about 9 journalists. The Brent Spar occupation and protest during this time was also filmed by Greenpeace and journalists aboard the Greenpeace supply vessel. Meanwhile, on May 15, 1995 at the G7 summit being held in Halifax, Nova Scotia, German chancellor Helmut Kohl publicly protested the Brent Spar dumping plan to British Prime Minister John Major.

Shell offshore vessel using water canons aimed at Brent Spar to discourage/dislodge Greenpeace activists on the structure. This is a later, mid-June 1995 photo, after two Greenpeace activists had re-boarded the Brent Spar via helicopter. AP photo.

Shell, meanwhile, had refused to meet with Greenpeace. At sea, Shell had begun using water cannons from it own vessels to bombard the Brent Spar activists and their rubber rafts. In court, Shell’s lawyers went after Greenpeace for trespassing. But on May 22nd, Greenpeace received a letter from some of Shell’s worker representatives in Germany expressing their “concern and outrage” over the rig dumping plan – which was quite embarrassing for Shell UK. The next day, May 23rd, Shell workers with police boarded the Brent Spar to remove the activists and journalists from the structure. The activists were jailed briefly in Aberdeen, Scotland. But by then, the televised media coverage had been running for days and a “David-vs.-Goliath” storyline had been cast over the offshore battle. The TV broadcasts had captured some of the water cannon bombardment attempting to dislodge the activists, which garnered sympathy for the activists throughout Europe. “… Joe Six-Pack won’t understand your technical details [about the dump-ing]. All he knows is that if he dumps his car into a lake, he gets fined….”

– Jochen Lorfelder, Greenpeace

Although the activists were removed from Spar by May 23, 1995, Greenpeace then called for a boycott of Shell service stations in continental Europe.

On June 1st in Hamburg, Germany, executives from Shell’s subsidiary met with Greenpeace, arguing that the dumping of the rig at sea was the best option scientifically. One of the Greenpeace reps at that meeting, Jochen Lorfelder, offered a public perception perspective: “…But Joe Six-Pack won’t understand your technical details [of the dumping]. All he knows is that if he dumps his car into a lake, he gets fined. So he can’t understand how Shell can do this.” Lorfelder also had some other more alarming information for Shell at the meeting, pointing to an independent survey showing that 85 percent of German motorists would support a Shell gasoline boycott. Lorfelder explained that in the four weeks it would take to tow the Brent Spar to its dump site in the North Atlantic Ocean – moving at a pace of about 1 mile per hour – a gasoline boycott could really have a considerable impact on Shell’s German gasoline revenues.

By June 10th, Greenpeace executive director Steve D’Esposito sent a 22-page report to the Shell board in London and released it to the public about a week later. The report charged that sinking the Brent Spar would release radioactive waste, heavy metals, and 5,500 tons of oil sludge into the ocean with unpredictable consequences. Greenpeace also charged that the released waste from dumping the Brent Spar would damage the food chain for fish in the area, reducing the fishing stocks. Greenpeace’s estimates of the oil and toxic materials on the Spar were over a hundred times those offered by Shell, and were later found to be quite overstated.

Another photo of a vessel using its water canons in an attempt to foil the Greenpeace activists at the Brent Spar.

Shell UK, meanwhile, on June 11, 1995, went ahead with their dumping plan, cutting the anchor chains of the Brent Spar to begin its towing out to sea. The gasoline boycott on the continent then began in earnest. In Germany, some politicians, trade unions, and the Protestant church supported the boycott of Shell’s 1,700 gas stations there. “We couldn’t believe the response,” said Jochen Vorfelder of Greenpeace Germany, referring to the boycott. “These ordinary people said they wanted to do something.” In Berlin, Shell Service stations reported a 30 percent drop in sales in the first two weeks of June 1995.

However, at some locations in Germany, the protest turned violent. On June 16th, 1995, a Shell gas station in Hamburg was firebombed in the middle of the night, and for a period of six days thereafter one report had it that about 50 Shell stations were damaged, two firebombed, and another shot at. The boycott soon spread to Denmark, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the UK. Government leaders in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and Denmark also called for a halt to the sinking.

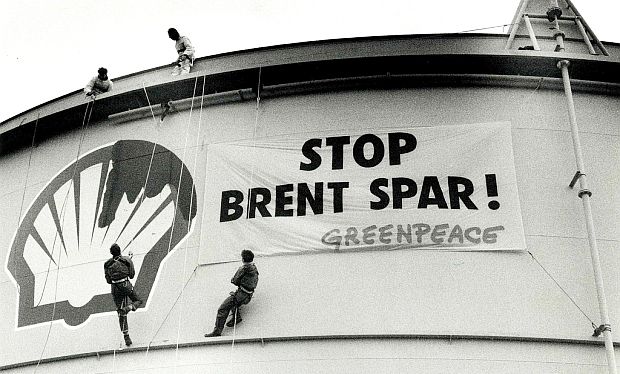

June 1995. Other Greenpeace demonstrations protesting the Brent Spar dumping occurred elsewhere in Europe, such as this “Stop Brent Spar!” banner being installed by activists on a large Shell Oil storage tank in Luxembourg.

UK Environment Minister Tim Eggar accused Greenpeace of “grossly exaggerating” the disposal problem, arguing that disposal on land would cause “very significant environmental damage.” Prime Minister John Major, holding forth in the British House of Commons, said Shell had his full support. Major even leveled some remarks at German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who had been critical of the Shell dumping plan earlier that week at a G-7 Summit held in Halifax, Nova Scotia in mid-June 1995.

Out in the North Sea, meanwhile, Greenpeace activists had tried boarding the Brent Spar a second time in May, but were unsuccessful. Then they tried again in mid-June 1995. This time, two Greenpeace activists re-boarded the Brent Spar by way of a dramatic helicopter drop at noon, with the activists later re-laying their protest banners on the helipad deck. Shell officials on nearby tug boats again used water cannons to try to stop the activists, nearly knocking the helicopter down at one point, according to Greenpeace.

Photo showing Greenpeace activists in motorized rubber raft trying to approach Brent Spar structure amid water cannons being fired from nearby vessels. This action occurred on June 16, 1995 after an earlier occupation of structure in May.

TV images of Shell security and British police spraying the protesters with the water-cannons were broadcast by the media worldwide, and especially in Europe, where they helped fuel demonstrations. There had also been continuing coverage in major European newspapers. Three London newspapers, for example – The Daily Telegraph, The Daily Mail, and The Daily Mirror – more or less had continuous coverage of the controversy, though with somewhat differing sympathies for the protest.

By June 19th, 1995, a Greenpeace advertisement appearing in national newspaper editions demanded that Shell accept its corporate responsibility. “The day Shell sinks the Brent Spar,” said the ad, “Shell’s reputation sinks with it.” Greenpeace had spent heavily on promoting its campaign to stop the dumping. Shell, by comparison, was outflanked – at least in the media.

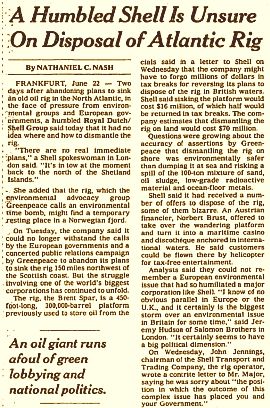

June 23, 1995. New York Times reporting on Shell’s troubles with its Brent Spar plans.

On June 20th, 1995 Shell’s directors at the Hague were deep into a three-hour session on the fate of their plan, after which they agreed to abandon the dumping. With that, Shell UK chairman Chris Fay met with UK Environment Minister Tim Eggar to inform him that a press release on the abandonment would be sent out within a few hours. Shell’s Fay admitted his company was in an “untenable position” because it had failed to convince other North Sea governments that dumping the rig was the best option. According to the company’s statement: “Shell UK has decided to abandon deepwater disposal and seek from the UK authorities a license for onshore disposal… Shell UK Ltd still believes that deep water disposal of the Brent Spar is the best practicable environmental option, which was supported by independent studies.”

Shell’s decision was not cheered by the UK government, with some officials openly critical of the company’s backing down. Prime minister John Major, for one, was quite angry and reportedly called the company’s board “wimps” for caving in to the pressure brought by Greenpeace, the European boycott, and national leaders such as Germany’s Helmut Kohl. Major had put his own prestige on the line supporting Shell’s claims that sinking the “Brent Spar” rig would do the least damage to the environment, saying at one point, it was the “right way” to get rid of it.

Out at sea, meanwhile, Greenpeace activists aboard the Brent Spar, noticed the structure was moving in a different direction. They soon received word that Shell’s disposal plan for the rig had been stopped, and the structure was now heading temporarily back toward Scotland, while Shell sought plans to moor the rig in Norway. The protestors on board the Brent Spar celebrated on the news, some lighting flares on the upper deck, as shown in the photo below (top deck, at left).

Four Greenpeace occupiers aboard the Brent Spar, upper left, celebrate on helicopter pad waving lit flares at the news that the Brent Spar was heading a new direction toward shore, and would not be dumped at sea.

Some at Greenpeace, however, were not gloating over Shell’s reversal. “It’s not a victory against Shell or the British government,” said Ulrich Jurgens, campaign director for Greenpeace International. “It’s a victory for the sea.”

The Brent Spar was finally towed and “parked” to a corner of the deep Norwegian sea near Stravanger. A week after Shell abandoned its plan, OSPAR voted 11-2 for a moratorium on disposal of decommissioned offshore installations in the North Atlantic, including the North Sea. However, Britain and Norway, the largest beneficiaries of North Sea oil and gas revenues, voted against the ban. Under the OSPAR convention, the suspension vote was not legally binding on dissenting countries. (The real success came three years later (1998), when the OSPAR conference (at a meeting of the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic) passed a general ban against sinking oil platforms.

Post-Mortem

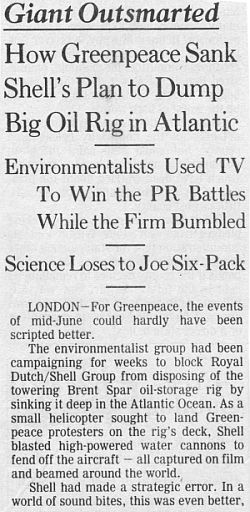

July 7, 1995. Headlines from front-page Wall Street Journal story on the Brent Spar battle.

“For Greenpeace, the Brent Spar shows that high-profile cases, properly framed and easily explained, can ignite widespread public interest, especially if the news media get plenty of good photo opportunities. It also shows that economic warfare may be the best way to wage eco-warfare. The attention grabbing tactics helped spark a boycott against Shell that cut sharply into gasoline sales and pushed the company to reverse course.”

A New York Times report about the same time found that Greenpeace’s appeal to the public was likewise boosted by the Brent Spar events, as the organization would gain in membership and funding.

Greenpeace, however, did not emerge unscathed, as the group was challenged on some of its arguments and also called out for its estimates of oil waste on board the Brent Spar. In late June 1995, an article surfaced from the British magazine Nature critical of Greenpeace’s scientific arguments opposing the dumping. Its authors argued that the metallic elements found in the structure, compared to those already found on the ocean floor and in undersea venting at the planned site, would make the damage from the Brent Spar “minimal” by comparison. In early September 1995, Greenpeace itself acknowledged in an apology to Shell, that it had overstated its case with incorrect data about toxic quantities due to inaccurate sampling measurements. It was later shown there were 150 tons of oil waste aboard the Brent Spar, not 5,000 tons, as Greenpeace had claimed. Still, Greenpeace maintained that the larger issue was dumping the structure at sea. Each retired rig jettisoned to the sea bottom would commit, on average, about 4,000 tons of “oil junk” to the ocean floor.

In the end, Shell did dismantle the Brent Spar on shore, using it to help build a pier in Norway. However, it is still unclear what the future holds for the numerous rigs, pipelines, and other oil junk now found in offshore regions all over the world.

A Daily Mail (London) newspaper photo from January 2016 showing a “graveyard”-like image of retired oil rigs parked off the coast of Scotland, hauled to their harbor moorings during a drop in oil prices as companies were then cancelling off-shore explorations.

Indeed, at the time of the Greenpeace action, the Brent Spar was only one of 6,500 offshore rigs worldwide and one of 416 oil platforms in the North Sea. In the British sector of the North Sea alone there were then 219 offshore installations, 53 of which were deep-water oil platforms then scheduled to be decommissioned over the next decade or so. Should deep-sea dumping of these structures become the standard disposal practice, what then will be the long-term impact of such practices for both ocean ecosystems and shipping safety?

October 2019

Battle Flares Anew

More than 20 years after the Brent Spar controversy, in October 2019, Greenpeace activists again boarded Shell offshore oil structures in the North Sea – this time, two Brent Alpha and Brent Bravo structures, unfurling a banner on one that read: “Clean Up Your Mess, Shell!” The Greenpeace activists were protesting plans by the company to leave parts of several of its old, decommissioned North Sea structures in place rather than entirely removing them.

October 2019. Greenpeace activists from the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark boarded two oil platforms in Shell's Brent field in protest against plans by the company to leave parts of old oil structures with 11,000 tons of oil in the North Sea. Climbers, supported by the Greenpeace ship Rainbow Warrior, scaled Brent Alpha and Bravo and hung banners saying, `Shell, clean up your mess!' and `Stop Ocean Pollution'. Source: Greenpeace

As of late 2019, Shell’s refusal to fully remove four old Shell oil platforms from the North Sea prompted complaint, not only from Greenpeace, but also European Union member nations Germany, Sweden, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. While Shell has removed the large topside parts of some rigs, at issue in this instance was an estimated 11,000 tons of raw oil and toxins still remaining in the base structures of three rigs – Bravo, Charlie and Delta – located in the East Shetland basin.

Environmentalists believe that such proposals are but the opening salvo of a much larger plan of “leave-them-in-place” rig abandonments, with oil firms intending to leave hundreds of offshore North Sea structures behind. Stay tuned. The battles over how to deal with the world’s offshore oil junk – including that in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico – will undoubtedly continue for many years ahead.

For additional stories on the environment and the fossil fuel industry at this website see the “Environmental History” topics page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing and continued publication of this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 15 April 2020

Last Update: 15 April 2020

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “The Brent Spar Fight, Greenpeace:

1995,” PopHistoryDig.com, April 15, 2020.

____________________________________

Books at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“Brent Spar,” Wikipedia.org.

Simon Reddy, No Grounds for Dumping: The Decommissioning and Abandonment of Offshore Oil and Gas Platforms, Greenpeace, 1995.

Auke Visser´s Esso UK Tanker’s Site, www. aukevisser.nl/uk.

“Murder At Sea: Scandal of Dumped Rigs That May Wipe Out Marine Life: Greenpeace Seize Oil Rig To Highlight Danger of Leaving Deserted Rigs To Rot At Sea,” Daily Mirror (London), May 1, 1995.

“Science: Dump The Rig – And Be Damned,” Daily Telegraph (London), May 31, 1995.

Richard L. Hudson, “Global Outcry Greets Shell’s Dumping Plan,” Wall Street Journal, 1995.

“Major And Shell Defy Efforts to Stop Brent Spar Sinking,” The Guardian ( London), June 17, 1995.

Nathaniel C. Nash, “Oil Companies Face Boycott Over Sinking of Rig,” New York Times, June 17, 1995.

“Seabed Must Not Become Rubbish Tip,” Daily Telegraph, June 20, 1995.

“Experts Warned Ministers of Oil Rig Disaster Two Year Ago,” Daily Mirror, June 20, 1995.

“Greed That’s Poisoning Our Seas: Shell Sinking of the Brent Spar Oil Rig,” Daily Mirror, June 20, 1995

“We Shell Not Be Moved: Dumping of Brent Spar Could Be The First of Many – There are 350 Rigs in the North Sea,” Daily Mirror, June 20, 1995.

“Mr. Green Targets Britain: As Britain is Tagged The Dirty Man of Europe, Green Heroes Talk of North Sea Ordeal: European Greens Target Britain;’s Polluting Companies,” Daily Mirror, June 20, 1995.

“30 Studies in Favour of Dumping,” Daily Telegraph, June 20, 1995.

Associated Press (London), “Greenpeace Tackles Shell; Offshore Platform Opposed,” Delaware County Daily Times (Swarthmore, PA), June 20, 1995, p. 21.

“Shocked Shell” Editorial, Wall Street Journal, June 20, 1995.

“Green For Danger,” Daily Telegraph, June 21, 1995.

Associated Press, “Shell Abandons Plans To Sink Oil Platform Off Scottish Coast,” New York Times, June 21, 1995, p. A-9.

Cacilie Rohwedder and Peter Gumbel, “Shell Bows to German Greens’ Muscle; Reversal of Plan to Sink Rig Shows Growing Clout of Environmentalists,” Wall Street Journal, June 21, 1995, p. A-15.

Shawn Pogatchnik, Associated Press, “Shell Bows to Environmentalists, Says it Won’t Sink Old Rig At Sea,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 21, 1995.

William Tuohy (London), “Shell Backs Down, Won’t Sink Oil Rig in Atlantic,” Los Angeles Times, June 21, 1995.

Bill Glauber (London), “Brent Spar’s Burial at Sea Canceled,” Baltimore Sun, June 21, 1995.

Associated Press (London), “Shell Backs Down; Oil Platform Won’t Be Sunk,” Delaware County Daily Times (Swarthmore, PA), June 21, 1995.

Financial Times, June 20 and 21, 1995.

Sue Leeman, Associated Press (London), “Shell Apologizes to Government After Backing Off Plan to Sink Oil Rig,” APnews .com, June 21, 1995.

Colin Brown, Nicholas Schoon & Peter Rodgers. “Shell `Wimps’ Apologise to Major,” Independent.co.uk, June 22, 1995.

Kyle Pope and Allanna Sullivan, “Shell’s Course Change Invites Questions; Bringing Oil Rig Ashore May Hold Its Own Hazards,” Wall Street Journal, June 22, 1995, p. A-12.

“A Triumph For The Forces of Ignorance: In The Wake of the Brent Spar Fiasco, One of Britain’s Most Distinguished Noble Prize-Winning Scientists Savages Greenpeace,” Daily Mail, June 22, 1995.

Kyle Pope, “Rig Incident Shows Britain Is Paler Shade of Green Than Rest of Europe,” Wall Street Journal, June 22, 1995, p. A-12.

Nathaniel C. Nash, International Business, “A Humbled Shell Is Unsure On Disposal of Atlantic Rig,” New York Times, June 23, 1995, p. D-2.

“Heroes Did Great Job: Fishermen Pay Tribute of Greenpeace Over Brent Spar,” Daily Mirror, June 23, 1995.

“Oil Rig Hero Gets Sell Discount Card,” Daily Mirror, June 24, 1995.

“Demo Man Wants Hug From Love: Brent Spar Hero Al Baker Arrive Back in Shetlands,” Daily Mirror, June 24, 1995.

“Dumping Rigs ‘Is Good For Sea Life’,” Daily Mail, June 30, 1995.

Bhushan Bahree, Kyle Pope, and Allanna Sullivan, “Giant Outsmarted: How Greenpeace Sank Shell’s Plan to Dump Big Oil Rig in Atlantic; Environmentalists Used TV To Win the PR battles while the Firm Bumbled; Science Loses to Joe Six-Pack,” Wall Street Journal, July 7, 1995, p. 1.

Marlise Simons, “For Greenpeace Guerrillas, Environmentalism Is Again a Growth Industry,” New York Times, July 8, 1995, p. 3.

Clifton Curtis, Biodiversiety/Oceans Political Advisor, Greenpeace International (Wash., D.C.), Letter-to-the-Editor, “You Can’t Hide, Even in The Sea,” Wall Street Journal, July 7, 1995, p. A-11.

Edward A. Ross, Jr., Response to Clifton Curtis Letter-to- the-Editor, “Frightening Seepage: Toxic Propaganda,” Wall Street Journal, July 21, 1995, p. A-11,

“Greenpeace Brent Victory ‘A Sad Day’,” Daily Mail, July 8, 1995.

“Oil Rig Sinking Blocked in Europe, Accepted in U.S. Gulf Coast,” Environmental Science & Technology, September 1, 1995, Vol. 29, No. 9, 406A.

“Deep Waters,” Daily Mail, September 6, 1995.

Reuters, “Greenpeace Apologizes To Shell Oil Company,” World News Briefs, New York Times, September 6, 1995, p. A-11.

“Greenpeace Fiasco,” Daily Telegraph, Sep-tember 7, 1995.

“Brent Spar Plan ‘Was Right’,” Daily Tele-graph, September 12, 1995.

Nature, September 29, 1995, vol. 375, p. 715.

“The Brent Spar Saga,” Environmental Health Perspectives / NIH.gov, September 1995, Vol 103, No 9, pp. 786-787.

“Brent Spar Was No Pollution Threat, Say Experts,” Daily Telegraph, October 19, 1995.

BBC, On This Day, June 20, 1995, “1995: Shell Makes Dramatic U-Turn,” News.BBC.co.uk.

Julian Oliver, “Learning The Lessons of Brent Spar Saga,” European Voice / Politico.EU, November 1, 1995.

Samuel Passow and Michael D. Watkins, “Sunk Costs: The Plan to Dump the Brent Spar,” Case Program, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 1997, CR1-97-1369.0, 19 pp.

Chris Rose, The Turning of the ’Spar, (Greenpeace: London), June 1998, 221 pp.

Paula Owen and Tony Rice, Decommissioning the Brent Spar, CRC Press, May 14, 1999, 192pp.

Rémi Parmentier, “Greenpeace and the Dumping of Wastes at Sea: A Case of Non-State Actors´ Intervention In International Affairs,” International Negotiation, Vol. 4, No. 3., 1999, Kluwer Law International (The Hague).

S. M. Livesey, “Eco-Identity as Discursive Struggle: Royal Dutch/Shell, Brent Spar, and Nigeria,” Journal of Business Communi-cation, 2001., Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 58-91.

Jack Doyle, “Shell At Sea” chapter in, Riding The Dragon: Royal Dutch Shell & the Fossil Fire, Boston: The Environmental Health Fund, 2002, pp. 141-145.

Thomas Mösch (jen) “Brent Spar Revisited, 10 Years On,” DW.com, June 20, 2005.

Shell International, Ltd., “Brent Spar Dossier,” May 2008.

Anders Hansen, “Claims-Making in the Brent Spar Controversy,” in Barbara Adam, Stuart Allan, Cynthia Carter (eds), Environmental Risks and The Media, Routledge, 2013, pp 57-71.

Nicholas A Jackson, Ronin Institute, “Shell Responds to the 1995 Ogoni and Brent Spar Crises: Industry-level Risk Management Through Corporate-Level Perception Man-agement,” ResearchGate.net, January 2013.

Brian G. Williams, “The Brent Spar: Coverage Analysis,” briangwilliams.us, Last Updated, 14 June 14, 2016.

Euan McLelland, “Is This the Graveyard of the World’s Economy? As Shares Crash Along with Price of Crude Oil, the Ranks of Massive Drilling Rigs Rusting in the Scottish Estuary Where They’ve Been Dumped since Demand Tumbled,” DailyMail.com (London), January 21, 2016.

Adam Vaughan, “Leave Oil Rigs in the North Sea, Say Conservationists,” TheGuardian.com, May 29, 2017.

Tom Lamont, “Where Oil Rigs Go to Die. When a Drilling Platform Is Scheduled for Destruction, it Must Go on a Thousand-Mile Final Journey to the Breaker’s Yard. As One Rig Proved When it Crashed on to the Rocks of a Remote Scottish Island, This Is Always a Risky Business,” TheGuardian.com, May 2, 2017.

Rex Weyler, “A Tribute to Jon Castle,” Greenpeace.org, January 25, 2018.

ipj/sms (AP, AFP, Reuters), “Berlin to Shell: Remove Old Oil Platforms in North Sea,” DW.com, October 17, 2018.

Philip Oltermann and Jillian Ambrose, “UK Facing EU Outrage Over ‘Timebomb’ of North Sea Oil Rigs; Germany Leads Complaint Against Plan to Leave Polluted Remains of Shell Rigs in Place,” TheGuardian.com, September 5, 2019.

Greenpeace International, “Greenpeace Acti-vists Board Shell Oil Rigs in Protest Against Plans to Leave Behind Oil in the North Sea,” Greenpeace.org, October 15, 2019.

__________________________________________________________