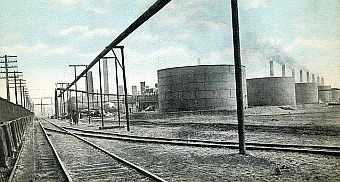

Circa 1910: Postcard rendition of oil storage tanks at southern tip of Lake Michigan where the sprawling Standard Oil refinery at Whiting, Indiana would become one the world’s largest. |

Late 1930s billboard, along a row of storage tanks (behind sign), touting the Whiting refinery as “the world’s largest.” |

Aerial view of refinery grounds, processing equipment and storage tanks covering some 1,600 acres at Whiting, Indiana. |

In 1955, the Standard Oil refinery at Whiting, Indiana was one of the largest oil processing centers in the world. The refinery became a centerpiece of John D. Rockefeller’s Midwest oil empire in 1889, part of his larger Standard Oil Trust that came to dominate the oil industry through the early 1900s.

Initially, the Whiting oil refinery processed high-sulfur, “sour crude” from the oilfields of Lima, Ohio, imported via Rockefeller-controlled railroads. The principal product was then kerosene for lamp lighting. But by the 1910s, with the rise of the automobile, gasoline became the primary product. In fact, at Whiting, some of Rockefeller’s scientists helped develop a refining process that would produce more gasoline from a barrel of oil.

Rockefeller’s company, Standard of Indiana, later became “Amoco” after Standard absorbed the American Oil Company in the 1920s. Amoco and the Whiting refinery, were later acquired by British Petroleum in 1998, the current owner.

But at the beginning, in 1889, the Whiting oil refinery rose in what was then a mostly rural area on the southern shores of Lake Michigan – a time when sand dunes were the most prominent feature in the area.

The town of Whiting – born of a railroad stop named “Pop Whiting’s Siding” after a rail engineer — grew with the refinery. Located about 16 miles from downtown Chicago, by the mid-1930s about 7,000 people were employed at the Whiting plant and the company’s Chicago offices.

By the early 1950s, Standard of Indiana ranked as the second-largest American oil company with annual gross sales of $1.5 billion. The refinery by this time had grown to encompass more than 1,600 acres, with many acres of storage tanks, refining towers, and processing equipment.

Standard of Indiana, like all oil companies of that era, had its growing pains and also had its share of spills, fires, and explosions. But on Saturday morning, August 27, 1955, an incident of historic proportion erupted there.

“Like The Sun Exploded”

It was early dawn that Saturday morning. A brand new hydroformer at the Whiting refinery was cranking up. It was also known by some as a “cat cracker,” as catalysts were used with naphtha and hydrogen under high pressure and heat to make higher-octane fuel. The hydroformer stood 260 feet high, or more than twenty-five stories tall. It was a giant piece of equipment, made of steel plate and concrete, designed to withstand the rigors of heavy operating pressures. In it’s production of high octane fuel, it would process 30,000 gallons of highly flammable naphtha every day. This hydroformer was one of the heaviest vessels ever made for oil refining at that time, then believed to be state of the art. But something went terribly wrong that Saturday morning.

Aerial photograph of the spreading August 1955 oil refinery fire at Standard Oil’s Whiting, Indiana complex. The 8-day fire, set by a processing tower explosion, would consume at least 45 acres of storage tanks and damage nearby homes and businesses. Two people were killed, another 40 injured, and 1,500 evacuated.

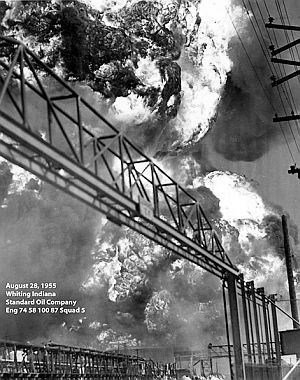

Without warning, at about 6:15 a.m., several explosions occurred at the giant hydroformer, and shortly thereafter – as some who were at the refinery that day would later recount – “all hell broke loose.” The initial blast tore apart the huge processing unit, hurling 30-foot long chunks of two-inch steel and countless smaller shards in all directions. “I thought the sun had exploded and that this was the end of the world,” said one woman, quoted in The Times newspaper of northwest Indiana. “There was a terrible noise and a big red flash.” The force of the initial blast broke almost every window in a three-mile radius. Smoke could be seen in Chicago and from 30 miles away.

Aug 28, 1955: In the town of Whiting, Indiana, looking south along Indianapolis Blvd, the Standard Oil refinery grounds to the left is where the initial explosion occurred, as the rising fireball shows. But there were also acres of storage tanks and more refinery stretching away from this area with additional storage tanks and refinery on the other side of this road.

Fiery debris from the exploding cat cracker rained down on the refinery grounds and nearby residential areas. Within the refinery, some of the flying metal and concrete landed on and punctured other oil storage tanks, igniting them in the process, touching off subsequent explosions. The Times and Chicago Tribune newspapers, among others, reported on the scene at the time, described “a flood of burning oil and naphtha” that washed over the refinery grounds and into Whiting streets and sewers. Residents were later warned about the risks of smoking and other open flames from home appliances that might ignite fumes backing up from the sewers. Some utility poles in the area also caught fire. (A short British Pathé newsreel film from 1955, shown below left, complete with dramatic music, captured some of the blaze that swept through the refinery and the Whiting community).

In residential areas near the refinery, flying projectiles damaged several homes, terrifying residents. A 3-year-old boy in one nearby home was killed in his sleep as a 10-foot steel pipe torpedoed through the roof of his bedroom.

In another instance, a 180-ton chunk of steel “as big as a five bedroom house,” according to The Times was hurled two blocks. That huge projectile, leveled a home and a grocery store on 129th Street, where the homeowner had left only minutes before the blast. Businesses, homes, garages and automobiles within a three mile radius of the refinery sustained substantial damage. Six miles from the explosion, some residents reported being knocked from their beds.

One family that barely escaped was that of Harvey Hunter and his wife Beverly and their two young children, Bonnie and Dennis. Harvey, a crane operator at Inland Steel in his day job, recounted the family’s horror to a Chicago Tribune reporter after he and his family had reached the Whiting Community Center for shelter:

August 1955: Onlookers watching the refinery blaze from a distance were surprised by a subsequent explosion and ran for their cars. Life magazine, Sept 5, 1955, Wallace Kirkland.

“We were thrown out of bed by the explosion. Chunks of steel pipe came thru the building, the windows and screens blew inwards, and the plaster fell from the ceiling.

“I picked myself off the floor and started looking for the children. Dennis’ bed was upside down and he was under it – covered with broken glass and plaster. Something had hit me on the head…

“I found my wife and daughter and the four of us got out of there in a hurry. We got into our station wagon and started down the alley but the way was blocked by a metal casting – it must have weighed 100 tons – that had been hurled there from the refinery. We turned back and got out at the other end of the alley and got here [community center shelter]…”

In addition to the boy killed in his home, one Standard Oil workman died of a heart attack, and more than 40 others were injured and sent to hospitals.

About 1,500 residents from some 600 homes were evacuated from the area to avoid further casualties as armed National Guard units patrolled the streets helping local police maintain order. Following the initial explosions, fire began consuming other parts of the refinery. By night fall on the first day, 60 million barrels of oil in storage tanks had gone up in flames.

For the next two days, the fire continued to spread, marching through the refinery’s tank farm acre-by-acre touching off further explosions, more refinery spillage, and additional fire. Spreading flames sometimes rose to heights of 300-to-400 feet.

Aug 28, 1955 Chicago Tribune headlines on the Standard Oil refinery fire indicate huge losses and “oil blaze out of control.” |

Aug 29, 1955 Chicago Tribune headlines indicate Standard Oil fire in check, but still burning, with residents kept from their homes. |

In the end, at least 67 storage tanks over some 45 acres had been completely destroyed. Oil and naphtha from ruptured tanks had also flowed into the Indiana Harbor Ship Canal.

Newspaper photos from inside the refinery told a story of the fire’s awesome heat and destructive power — railroad rails that “resembled strands of spaghetti, bent by the extreme heat and force of the explosion,” according to one report. Some freight and tank cars were melted by the intense heat generated.

In battling the inferno, numerous Standard Oil workers were enlisted to fight the blaze and fire departments from Hammond, East Chicago, Gary, Calumet City, Dolton and Chicago rushed to help – more than 6,000 in all joined the fight.

As the days went by, the firefighters realized their task was to contain rather than extinguish the blaze. They began building large sand barricades at the perimeter of the fire in an attempt to keep burning oil from spreading to other areas of the refinery. At times, however, there was fear the blaze would spread to the nearby Sinclair Oil refinery, creating an even greater catastrophe. But on the second day of the blaze, the fire was said to be “under control,” although sill burning.

A YouTube viewer commenting on one of the Whiting fire films found on the web, offered an eye-witness account of the 1955 blaze with the following: “I lived two streets in front of this [fire] on White Oak Ave. When the explosion happened we thought it was the Atom Bomb. Everyone ran from their homes, some people were moving their furniture out. By the time we got to the corner of Indianapolis Blvd., the entire block at Standard was on fire and oil tanks were exploding. I was 11 years old. We left for East Chicago and spent a week at my grandmother’s home. Sand trucks were brought in from the Dunes to help contain [the refinery fire]. The tanks were exploding and we could feel the heat by just standing in the front yard of my grandmother’s home miles and miles away. We left everything, including the dog and our bird…”.

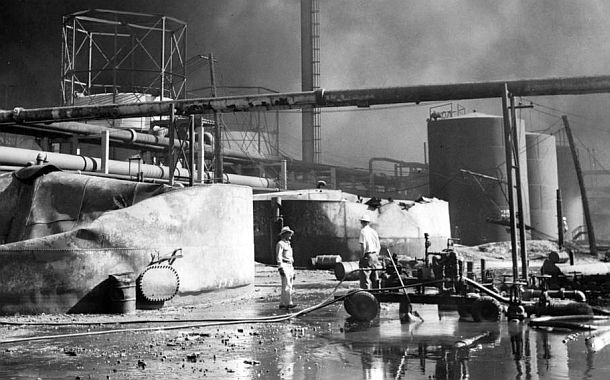

Aug 1955: Life magazine photo of Standard Oil workers at Whiting trying to contain burning oil and sequential tank explosions by building sand barricades to keep the oil & fire from spreading to other parts of the 1,660-acre refinery.

When the last of the fires were finally put out on September 4, 1955, the area was declared a National Disaster. The company’s own internal publication, The Standard Torch of October 1955, offered an initial accounting: “Eight days and five hours later, the last flame was extinguished. By then, 45 acres of the refinery lay in ruins. Seventy tanks were crumbled and burned out. Three process units were destroyed. Twisted, fire-blackened steel lay about as grim reminders.. .. Damage was estimated to be in excess of $10 million dollars, all but one million of which was insured.” Other estimates put the figure at $30 million (or roughly between $87 million and $273 million in 2015 dollars).

Two men at center survey the damage in a portion of the burnt-out Standard Oil refinery, then still smoldering, with the remains of two crumpled and distorted giant storage tanks to the left. Whiting oil refinery, Aug 1955, Chicago Tribune photo.

A year after the fire, Standard Oil was back to business as usual, having rebuilt the damaged parts of the refinery and soon operating at 100 percent capacity again. But the terror the incident created among workers and in the community was very real. One resident, Gayle Kosalko, would later note, “that explosion caused Whiting’s population to go from 10,000 people to 5,000.” And indeed, after the incident, Amoco/Standard took the opportunity to buy up land near the refinery, and many homes and businesses that were destroyed or damaged by that fire or abandoned were leveled and never rebuilt.

Boiling fire on top of large tank at left, with twisted metal thrown from explosion in the foreground. Whiting refinery fire, Aug 1955. |

Photo of some of the large debris thrown by the explosion into residential areas. Whiting refinery fire, Aug 1955. |

In August 2005, at the 50th anniversary year of the big blaze at the Whiting refinery, a couple of survivors from the incident spoke with reporter Oliva Clarke of The Times, recalling its effects. Norb Dudzik, 62, of Whiting noted: “You could just feel the heat off of it. …[W]e drove through some of the neighborhoods. It was almost like you’d seen a tornado with cars flipped upside down and houses — some destroyed and some moved off their foundation.”

George Orr, 89, of Hessville, Indiana and an instrument technician supervisor at the time of the blaze who was also recruited to fight the fire for several days, explained:

“The flames were as high as telephone poles on both sides of us and the heat was unbearable…I wore ordinary work clothes, and of course we had to wear hard hats and hard-toed shoes. …If you refused to fight the fire, you didn’t have a job at Standard Oil in the morning.”

At the fire’s 60th anniversary, in August 2015, the Historical Society of Whiting/Robertsdale sponsored a screening of a new documentary on the fire titled, “One Minute After Sunrise.” The half hour film was the result of a year’s worth of research and personal interviews aimed at preserving and documenting this episode of Whiting and Standard Oil history. (See also John Hmurovic’s book, One Minute After Sunrise: The Story of the Standard Oil Refinery Fire of 1955.)

Other Incidents. The 1955 fire and explosion at the Whiting refinery was not the first such incident there, nor would it be the last. On July 4, 1921, eight workers were killed and more than 40 others injured when a series of gasoline pressure sills exploded and burned at the refinery. In September 1941, a nine hour conflagration at the refinery killed one man and injured 20 others. That blaze also destroyed more than 30 oil storage tanks and half a dozen buildings with a loss estimated at $100,000 (1941 dollars). Another fire and explosion in July 1946 ripped through the refinery, this time with only one worker injured. In the years following the 1955 inferno, there continued to be more incidents at the Whiting refinery of one kind or another – fires, leaks, spills, explosions, and or pollution. These occurred more or less on a regular basis, both large and small, some years worse than others, but continuing to the present day under the auspices of BP, the refinery owner since 1998-99.

|

Whiting Refinery Incidents Over the years, the Whiting oil refinery has had its share of incidents, large and small, including numerous fires and explosions, many of the smaller variety, some not always reported. Included below is a sampling of some of the documented incidents occurring at the Whiting oil refinery under Standard/Amoco management in the 1957-1991 period: 23 Nov 19572 workers killed in refinery fire. Sources: Don Jordan, “Amoco Shutdown is Part of Firm’s History,” The Times (of Northwest Indiana), April 13, 1990; Rebecca Vick, “Amoco Toxic Gas Leak Is Second This Week,” The Times, December 29, 1990, p. B-1; Susan Erler and Phil Wieland, “OSHA Orders Shutdown of Reactor,” The Times, April 12, 1990; Rebecca Vick, “Leak Forces Amoco Employees to Move,” The Times, September 25, 1991, p. B-1. |

1988-1990

By the late 1980s, incidents at the Whiting refinery had the attention of state and federal safety officials. On October 30, 1988, an explosion and fire killed three workers and injured another. The explosion occurred in the oxidizer unit, a vessel 70 foot high with a 32-foot diameter. When the explosion occurred, the entire unit rose 40 to 50 feet off the ground.By 1988-1990, Indiana officials were calling the Whiting refinery the most dangerous workplace in the state. It also coated workers with 500-degree asphalt. The unit had begun to malfunction several days earlier, but the company kept it running in order to maintain production. Two previous explosions in the same unit in 1988 had injured 18 workers. The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) cited Amoco for a wide variety of violations and fined the company $300,000 for the infractions. In fact, for the 1988-1990 period, Indiana officials were calling the Whiting facility the most dangerous workplace in the state. “No one else has that kind of safety record,” said Kenneth Zeller, Indiana Commissioner of Labor at the time. In April 1990, the Indiana Occupational Safety and Health Administration — citing “imminent danger” and “a strong possibility of catastrophe” — ordered Amoco to shut down a chemical reactor in one of the refinery’s key Ultraformer processing units. Officials ordered the shut down after inspecting the unit following an anonymous complaint from a worker at the plant who reported “hot spots” in the reactor. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, at least two more people were killed at the Whiting refinery and several others injured in at least five other incidents.

Artist’s rendering of oil storage tanks at Whiting, circa 1940s or so.

Leaking Oil

In January 1991, after conducting a two-year, in-house investigation, Amoco officials revealed a 16.8 million-gallon leaked underground plume of petroleum products beneath the Whiting refinery. The company reported that 150 ground-water monitoring wells defined a plume of lubricating oils and gasoline components, including benzene, of between four and 18 inches floating on groundwater beneath much of the plant. Amoco sent 500 information packets to residents in a 12-block area in Whiting and the Robertsdale section of Hammond notifying them of the findings and offering free testing for benzene and combustible vapors. At the time, Amoco officials said the situation did not present an immediate safety or health hazard” for people living near the plant. The plume, they said, was formed over the plant’s 102 years of operation, a time when wooden and metal storage tanks leaked oil products into the ground. At least two class action suits were brought against Amoco in the 1990s claiming the company was negligent for allowing oil to leak into city sewers and beneath the community.

BP Acquires Amoco

One artist’s rendering of the “merging” of Amoco & BP.

Over the years since, BP has had a mixed record at the Whiting refinery. For example, in May 2009, EPA issued a notice of violation to BP for toxic air pollution at the refinery.

According to EPA, for nearly six years, under BP’s watch, the refinery emitted cancer-causing benzene at its wastewater treatment plant without proper air pollution control equipment.

BP stated at the time there was no evidence that humans or the environment were harmed. The violations occurred between 2003 and 2008. In 2008, the BP plant totaled just over 100 tons of benzene waste – nearly 16 times the amount allowed, according to the EPA. Similar violations for benzene waste also occurred between 2003 and 2008.

By 2013, BP stated that it had invested $3.8 billion to modernize the Whiting refinery, primarily to make it capable of processing of heavier crudes – i.e. tar sands from Canada and other crude. BP stated that its “modernization” was essential to the long-term viability of the refinery, and included $1.4 billion for “environmental enhancements” such as wastewater improvements, emissions reductions, and systems to remove sulfur from gasoline and diesel.

Yet today, one of BP’s by-products in refining the sludgy tar sands crude is an unwelcome substance called petroleum coke, or “pet coke.” Refining heavy crudes produces significantly more pet coke than conventional crude oil. And BP’s refinery at Whiting has tripled its yield of pet coke since expanding the refinery to process more of the unconventional tar sands oil. Whiting now yields about 6,000 tons of pet coke every day, or about 2.2 million tons annually.

|

“The Daily Damage” This article is one in an occasional series of stories at this website that feature the ongoing environmental and societal impacts of industrial spills & explosions, fires & toxic releases, air & water pollution, and other such occurrences. These stories will cover both recent incidents and those from history that have left a mark either nationally or locally; have generated controversy in some way; have brought about governmental inquiries or political activity; and generally have taken a toll on the environment, worker health and safety, and/or local communities. My purpose for including such stories at this website is simply to drive home the continuing and chronic nature of these occurrences through history, and hopefully contribute to public education about them so that improvements in law, regulation, and industry practice will be made, yielding safer alternatives in the future. |

While petroleum coke can be used as a heating fuel in some instances, or as a raw material in manufacturing, piles of the stuff from the Whiting plant and other U.S. refineries have produced swirling dust storms in areas where it’s stockpiled, raising public health concerns and angering nearby communities.

EPA has noted that significant quantities of fugitive dust from pet coke storage and handling can present a health risk. Particles that are 10 micrometers in diameter or smaller are of special concern to EPA, as these particles can pass through the throat and nose and enter the lungs, and once inhaled, can affect the heart and lungs and cause serious health effects.

Residents and community activists in the Whiting area have also raised concerns about the health effects of increased air pollution that comes with the use of flaring at the refinery – stack “flares” being a kind of safety valve feature found in all refineries, yet still a process that can sometimes be abused or used to compensate for more serious systemic shortcomings within the refinery. Others have also expressed worries about tar sands-induced pipeline leaks near the refinery, given that tar sands have a more corrosive effect on pipelines.

Additional stories at this website on oil and the environment include, for example: “Burning Philadelphia,” a story about the 1975 Gulf Oil Co. refinery fire in that city; “Texas City Disaster,” about BP’s negligence in the March 2005 Texas City, TX oil refinery explosion & fire that killed 15 workers and injured another 180, including 60 Minutes TV coverage and details on related litigation; and “Burn On, Big River…,” about the historic pollution and river fires on the Cuyahoga River in Ohio. Additional environmental stories can be found at the “Environmental History” topics page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please consider making a donation to help support this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

_________________________________

Date Posted: 21 August 2015

Last Update: 18 May 2022

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Inferno at Whiting – Standard Oil: 1955,”

PopHistoryDig.com, August 21, 2015.

_________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Aug 27, 1955: Explosion at the Whiting refinery as seen looking north on Berry Ave. from 129th St. Original Chicago Tribune caption noted: “A dark mushroom cloud, 8,000 feet high and visible for 30 miles, obscured the sun, effectively turning day into night.” Photo, John Austad |

Part of the destruction from the 1955 Whiting oil refinery explosion & fire. Investigative worker in foreground is inside large piece of structural metal thrown there from explosion. |

Another aerial photo of the August 1955 Standard Oil refinery fire at Whiting, Indiana taken from a different perspective. |

August 1955: Photo of Whiting fire taken from inside the refinery, it appears, by a firefighting unit, according to photo's notation. |

“Standard Oil,” Whiting Public Library, Whit-ing, Indiana.

“Standard Indiana,” ChicagoHistory.org.

“Whiting, Indiana,” ChicagoHistory.org.

“Fire Loss Tops 10 Millions; Whiting Oil Blaze Out of Control,” Chicago Sunday Tribune, August 28, 1955, p. 1.

“Food and Clothing Rushed to Aid Homeless Families,” Chicago Sunday Tribune, August 28, 1955, p. 1.

“List of Dead and Wounded in Whiting Refinery Fire,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 28, 1955; pg. 2;

“Refinery Giant Among Giants; Sprawls Across 1,660 Acres,” Chicago Sunday Tribune, August 28, 1955, p. 3.

“Big Mushroom Cloud Visible 30 Miles Away,” Chicago Sunday Tribune, August 28, 1955, p. 4.

“Standard Head Pledges Quick Aid to Victims,” Chicago Sunday Tribune, August 28, 1955, p. 4.

“Oil Fire in Whiting Checked,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 29, 1955, p. 1.

“Many Return to Homes; Oil Fire Abating,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 30, 1955, p. 1.

“The Whiting Fire,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 30, 1955, p. 20.

“Standard Oil Seeks to Buy Whiting Land,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 2, 1955, p. B-2.

“Standard Oil Bids for Homes in Blast Area,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 3, 1955, p. 8.

“Fire in Whiting Oil Refinery Finally Out,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 5, 1955, p. B-4.

“At An Exploding Indiana Refinery, Frus- trated Firefighters and Fleeing Onlookers” (photos, Wallace Kirkland), Life, September 5, 1955, pp. 22-23.

“Hint Whiting Fire Source of Lake Oil Slick,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 19, 1956, p. B-8.

“Oil Refinery Fire in Whiting Is Nearly Out,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 31, 1957, p. 7.

“Two Workmen Killed in Oil Refinery Fire,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 23, 1957, p. 4.

William Gaines, “Huge Whiting Oil Fire Was 10 Years Ago, But Memories Still Burn; Industry Improves Safety Measures Thru Probes,” Chicago Tribune, August 29, 1965, p. A-6.

“Refinery Blast Recalls Whiting’s 1955 Standard Oil Explosion,” NWItimes.com, March 28, 2005.

Olivia Clarke, “Memories of Disaster,” NWItimes.com, Saturday, August 27, 2005.

“Whiting, Indiana – August 27, 1955,” Industrial Fire World, Volume 16, No. 2.

Robert Kostanczuk, “1955 Whiting Refinery Fire Ranks as Catastrophic Industrial Accident,” HubPages.com.

“Early Whiting History,” Whiting Public Library, Whiting, Indiana.

British Pathé (Newsreel), “Ten Million Dollar Oil Blaze (1955),” YouTube.com.

Associated Press, “1,500 Flee As Blasts, Fire Hit Oil Refinery,” Toledo Blade (Toledo, OH), February 12, 1979, p. 1.

UPI, “Refinery Blaze Put Out; 400 Return To Homes,” Bangor Daily News, February 13, 1979.

“$100,000 Damage Caused by 9 Hour Fire at Refinery; 1 Killed, 20 Others Hurt in Whiting Blaze,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 25, 1941, p. 14.

Oil, Chemical & Atomic Workers (OCAW), “Fatal Oil Accidents Involving OCAW Members, 1984-1989,” January 1990.

Chris Isidore, “Memorial Due; Probes Lagging,” Post-Tribune, Sunday, April 22, 1990, p. F-1

Susan Erler and Phil Wieland, “OSHA Orders Shutdown of Reactor,” The Times, April 12, 1990.

Chris Isidore, “Tips Spurred Amoco Probe,” Post-Tribune, April 14, 1990, p. A-1.

Caleb Solomon, “Rash of Fires at Oil And Chemical Plants Sparks Growing Alarm,” Wall Street Journal, November 7, 1989, p. 1.

Laurie Goering, “Amoco Finds 16.8 Million-Gallon Leak,” Chicago Tribune, January 25, 1991.

“Area Cities Sit Atop Massive Sea of Oil,” The Times (Northwest Indiana), January 27, 1991.

Rebecca Vick, “500 Added To Lawsuit Against Amoco,” The Times, February 1, 1992, p. B-1.

Andrea Holecek, “Amoco: Most Of Leak Stayed At Refinery,” The Times, June 5, 1992, p. A-1.

Associated Press, “Oil Company Earmarks Billions To Meet Regulations,” New York Times, May 15, 1992.

Jack Doyle, Crude Awakening: The Oil Mess in America, Friends of the Earth, Washington, DC, October 1993, 350pp.

Sallie L. Gaines, “Huge Deal Remakes Amoco Into A Global Powerhouse; Giant To Combine With BP In Merger Worth $53 Billion,” Chicago Tribune, August 12, 1998.

Kari Lydersen, “Pollution Fight Pits Illinois vs. BP, Indiana; Upgrade of Oil Refinery Would Discharge More Pollutants Into Lake Michigan,” Washington Post, August 23, 2007.

Kari Lydersen, “Community Is Torn Over Expansion of Oil Refinery,” New York Times, September 15, 2011.

Anna Simonton, “Subsidy Spotlight: Paying the Price of Tar Sands Expansion,” Oil Change International, October 16, 2014.

“Standard Oil Refinery Fire of 1955,” Photo gallery (11 photos), Chicago Tribune, August 2015.

John Hmurovic, “Whiting’s 4th of July Disaster” [1921], The Whiting – Robertsdale Historical Society / wrhistoricalsociety.com, May 2021.

_____________________________________________