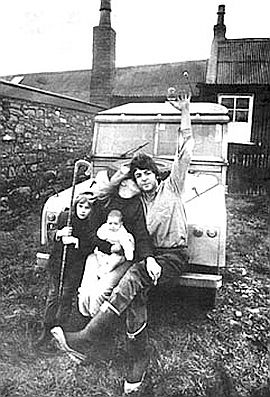

Paul McCartney, shown with Linda & family in a November 1969 Life magazine cover photo taken in Scotland to dispel popular rumors that Paul was dead.

But amidst all of this came a “pop rumor” that Beatle Paul McCartney was dead; a rumor that ran wild for time all around the world.

As the story went, McCartney was supposedly killed in a 1966 car crash and had been quietly replaced by a look-alike to spare Beatles’ fans the grief and keep the group on track. It all proved to be a giant hoax, of course – a big false story – as the November 7, 1969 Life magazine cover story at right indicates.

The Life story was one of the more mainstream reactions that emerged during that time to help investigate the rumor, and finally dispel it as a hoax. Yet the tale about Paul’s demise, still to this day, survives in some corners as urban legend.

But as the story unfolded at the time, the whole affair helped raise the Beatles’ “mystical” appeal and also, no doubt, to sell a lot more of their music – not that they were having a hard time doing that.

What follows below is a recounting of the “Paul-is-dead” story. But first some Beatles’ context at that time — which is probably the more interesting story – occurring roughly during calender year 1969 and into early 1970, leading up to the “Paul-is-dead” rumor, including some of the group’s final recording sessions, and in 1970, the break-up of the Beatles.

In January 1969, there was plenty of Beatles’ music in the air, and plenty of Beatles’ recording activity going on in various London studios. This, despite the fact that the group was having serious internal difficulties. The strains had begun upon their return from India in 1968 (see “Dear Prudence” story), and continued through their 1968 recording sessions for the “White Album.” By1969, despite the output of what would prove to be quite incredible music, the band was barely operating as a group. After arguments and frustrations, there had been walkouts by Ringo at one point in 1968, and George in 1969 — although both returned. At other times, each member did parts of songs or played instruments separately that were later combined in the studio. For the adoring public, however, the Beatles’ discord was largely out of sight, and for the most part, unknown. Beatles’ music, meanwhile, was all over the airwaves then and frequently riding high on the pop charts.

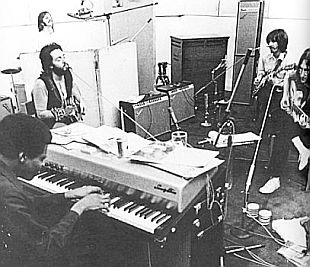

The Beatles at January 1969 London rooftop jam session (Ringo obscured; Billy Preston not shown). Click for book.

Also that month, much of the music that would be used for the Let It Be album was being recorded by the Beatles, though the album itself would not appear for another year or so, as it would be shelved and reworked. Other studio recording was also occurring.

In late January 1969, the Beatles were filmed in a rooftop jam session – in what would prove to be their last public “concert” together – performing several songs on the roof at Apple’s building on 3 Savile Row, London. The 42-minute session of songs was filmed for the Beatles’ movie, Let It Be

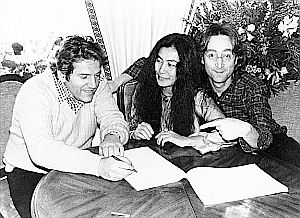

Business agent Allen Klein shown with Yoko Ono and Beatle, John Lennon. Klein became a source of some internal Beatles’ discord in 1969 and a later lawsuit. Click for his book.

A stock struggle also ensued about this time over the Beatle’s Northern Songs music catalog, as their music publisher, Dick James, had sold his shares of Northern Songs in March 1969 to Associated Television (ATV). This would become the much-publicized “Beatles music catalog” that Michael Jackson would later acquire. But that’s another story (see “Michael & McCartney“).

The Beatles at work in London studio in 1969 with keyboard player Billy Preston, lower left. Click for related sessions book.

In April, the Beatles’ single “Get Back” with “Don’t Let Me Down”on the B side, was released and rose to No. 1 in several countries.

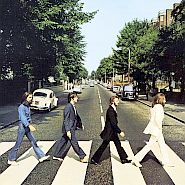

Meanwhile, through much of that year, the Beatles continued to work in the recording studio on music and lyrics for their Abbey Road album. This work generally ran between February and August 1969 at three London studios, with keyboardist Billy Preston brought in to help out on electric piano and organ for some of the sessions.

Also during this time, in the middle of the Abbey Road work, around July 4th, 1969, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, released a solo recording, “Give Peace A Chance” in the U.K and the U.S. This song, credited to the Plastic Ono Band, became the first solo single by a member of the Beatles, and a clear signal of where things were headed.

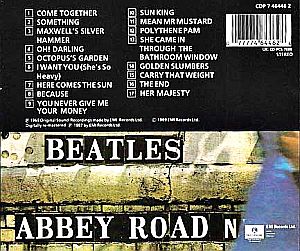

The back cover of the Beatles’ 1969 album, “Abbey Road,” listing 17 tracks. Click for 3-CD 50th anniversary set.

The Rumor

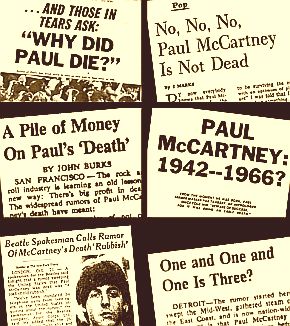

A collage of news stories on the "Paul-is-dead" rumor, 1969.

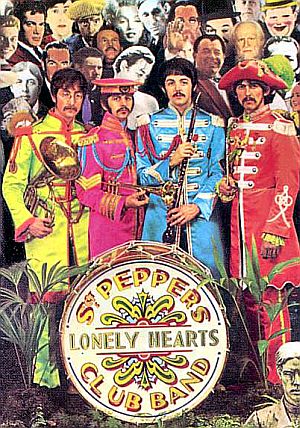

“…This album also started the hints that all was not right with the Beatles, especially Paul. On the front cover a mysterious hand is raised over his head, a sign many believe is an ancient death symbol of either the Greeks or American Indiana. Also, a left-handed guitar (Paul was the only lefty of the four) lies on the grave at the group’s feet…

“…On the back of the same album…George is pointing toward a phrase from the song “A Day in the Life” pertaining to a certain Wednesday morning at five a.m. when some famous but unnamed person “blew his mind out in a car.”…

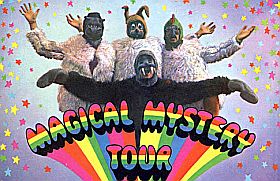

And on it went, citing other Beatles albums, such as Magical Mystery Tour, clues in its songs, and even a revelation about a phone number when the album cover was held up to a mirror.

Clue hunters in 1969 thought the hand over McCartney’s head on “Sgt. Peppers” was an Eastern symbol of death.

The Detroit radio DJ, Russ Gibb, did the reverse playing, reporting on the airwaves that he thought he heard phrases to the effect of, “turn me on, dead man.” Soon, Gibb was telling his listeners what he had found and was also adding to the list of clues.

Meanwhile, on October 14, 1969, college students at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor published a satirical review of The Beatles’ Abbey Road album in The Michigan Daily. This story stoked the “McCartney-is-dead” claim with “new evidence,” offering various “clues,” some supposedly found in any number of Beatles’ songs and/or album covers. This story, in turn, was picked up by various newspapers across the U.S. and escalated nationally.

On October 21, 1969, helping to spread the rumor nationally, a radio disc jockey at New York radio station WABC, discussed the “Paul-is-dead” rumor at length for over an hour. This occurred during the very early morning hours of WABC’s broadcasting reach, when the station’s signal could be heard in 38 states and beyond. At this point, the “Paul-is-dead” rumor was spreading like wildfire. Fans at Hofstra University even formed a special group named: “Is Paul McCartney Dead Society.”

Beatles’ "Magical Mystery Tour” album (1967) became part of the hunt for clues in ‘Paul-is-dead’ rumor. Black walrus was Paul, a bad omen? Click for CD.

John Lennon, in the final section of the song “Strawberry Fields Forever,” was supposedly heard saying in the background something like, “I buried Paul,” when actually the suspect phrase was either “I’m very bored” or “cranberry sauce,” according to various reports.

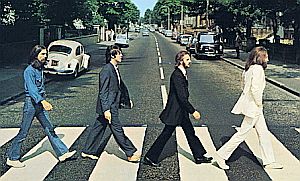

More “Paul-is-dead” imagery from Beatles’ “Abbey Road” album, from left: George as gravedigger, Paul the corpse, Ringo mourner, and John the preacher. Click for wall art.

Paul McCartney getting a kiss from wife Linda as they sit on bumper of Range Rover with baby Mary and Linda’s daughter Heather at their farm in Scotland. Photo, Life, 1969. Click for Paul & Linda's 'Ram' album.

In 1969, of course, there was no “always-on-media” — no internet, no People magazine, or TV-equivalent Access Hollywood or Entertainment Tonight. Under such media-deprived circumstances, more traditional journalistic sleuthing techniques were used to investigate the rumor.

Life magazine, the popular photo-journalist -styled news and culture weekly, dispatched a team from London, including reporter Dorothy Bacon, to track down McCartney in Scotland (see sidebar story below).

It was this London team, with photographer Robert Graham, that found McCartney at his farm, photographing him with his family for the Life magazine cover story of November 7, 1969 (shown at top of this article).

When McCartney was contacted by Life’s reporter, he speculated that the rumor might have started because he, McCartney, had been out of contact for a time and hadn’t been in the press much, which he didn’t regret.

“I have done enough press for a lifetime,” he told the Life reporter, “and I don’t have anything to say these days. I am happy to be with my family…”

He also added that he was essentially chilling out, taking some serious down time: “I was switched on for ten years and I never switched off. Now I am switching off whenever I can. I would rather be a little less famous these days.”

NY TV guide listing the F. Lee Bailey TV special on the ‘Paul-is-dead’ hoax story.

|

Life Finds McCartney Life magazine sent a team of London correspondents and a photographer to the remote reaches of Scotland on an un- announced visit to Paul McCartney’s farm. Hoping to avoid detection, the Life team hiked four and a half miles across cold moors and muddy fields until they approached the farmhouse of the missing Beatle. However, McCartney’s sheepdog, “Martha,” soon began barking at the interlopers. Paul then ran outside and began yelling at the reporters, charging them with trespassing. The photo- grapher in the group, Robert Graham, began snapping pictures of an enraged McCartney, and for his efforts, Graham was drenched with a bucket of water. The Life team then retreat- ed down the road. McCartney meanwhile, back in his kitchen, reviewing what had just happened, realized he had been perhaps a bit too harsh. He then jumped into his Land Rover, caught up with the group, and invited them back to his house for a cup of tea. After some discussion, a bargain was struck. Paul agreed to give the Life correspondents an exclusive interview. In return, Robert Graham agreed to give Paul the film in his camera. And Paul, in remarks to journalist Dorothy Bacon, said in part, “…Can you spread it around that I’m just an ordinary person who wants to live in peace?…” |

The “Paul-is-dead” hoax lasted for about two months in its most heated form — from about September through December 1969. If nothing else, the rumor probably helped fuel the sales of Beatles’ albums, including those with supposed “Paul-is-dead” imagery or symbolism. The episode proved a big enough event that it became the subject of several books, articles, lectures and academic papers. Among the books, for example, are American journalist Andru J. Reeve’s 1994 book Turn Me On, Dead Man, and another in 1997 by English author Benjamin Fitzpatrick, Rumours From John, George, Ringo and Me.

By mid-January 1970, in any case, it was the Beatles’ group that was dead – not Paul McCartney. At that point, each of the four Beatles separately began planning or beginning their solo careers. John and Yoko had already been recording. On April 10, 1970, Paul McCartney released his first solo album, McCartney. A few days later, Paul publicly announced the end of the Beatles. At about the same time, the Beatles’ previously-produced and recorded Let It Be album was released, followed by Let It Be the movie. That album became the Beatles’ 14th No. 1 album. Two singles from Let It Be — “The Long and Winding Road” and “Let It Be” — also became No. 1 hits.

Documents filed on December 31, 1970 officially ended the legal entity known as The Beatles. Three years later, John, George and Ringo split with Allen Klein and sued him. Still, during this tumultuous year of 1969 – marking their final disintegration as a group – the Beatles still managed, with help from their producer, George Martin, to turn out some of their most enduring and most loved music.

For a closely related story see, “McCartney: Amazed – The Paul & Linda Story,” which covers roughly the same time period around the Beatles’ break up, as well as Paul & Linda McCartney in Scotland during and after that time, their marriage and family, Paul’s first solo album, the emergence of Wings, and more. Additional stories on the Beatles can be found at the “Beatles History” topics page. Other story choices can be selected at the Home Page, the “Annals of Music” page, or the Archive.

Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing and continued publication of this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

_________________________________

Date Posted: 7 March 2011

Last Update: 6 February 2024

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “The Paul-Is-Dead Saga, …And Beatles’ Demise:

1969-1970,” PopHistoryDig.com, March 7, 2011.

___________________________________________

Beatles Music at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Tim Harper, “Is Beatle Paul McCartney Dead,” The Drake Times-Delphic (Drake University, Iowa), September 17, 1969.

Fred LaBour, “McCartney Dead; New Evidence Brought to Light” The Michigan Daily (Ann Arbor, MI), October 14, 1969, p. 2.

Brian D. Boyer, “Paul McCartney Dead? Campuses Swept by Beatle Rumor,” Chicago Sun-Times, October 21, 1969, p. 1.

B.J. Phillips, “McCartney ‘Death’ Rumors,” Washington Post, October 22, 1969, p. B-1.

“Beatle Spokesman Calls Rumor of McCartney’s Death ‘Rubbish’,” New York Times, October 22, 1969, p. 8.

John Neary, “The Magical McCartney Mystery,” Life, November 7, 1969, pp. 103-105; and Dorothy Bacon, ” ‘I Want To Live In Peace’,” Life, November 7, 1969, p. 105.

John Burks, “A Pile of Money On Paul’s ‘Death’,” Rolling Stone, November 29, 1969, p. 54.

“The Beatles,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, Rolling Stone Press, New York, 3rd Edition, 2001, pp. 56-59.

“Paul Is Dead,” Wikipedia.org.

Andru J. Reeve, Turn Me On, Dead Man: The Beatles and the ‘Paul Is Dead’ Hoax, Popular Culture Ink., 1994

Benjamin Fitzpatrick, Rumours From John, George, Ringo and Me, 1997.

Brian Moriarty, “Who Buried Paul?,” Illustrated Transcript of a Lecture at the Game Developers Conference, San Jose Convention Center, March 17, 1999 on St. Patrick’s Day 1999, as a featured lecture, Ludix.com, detailed accounting of “Paul-is-dead” hoax.

Gary R. Patterson, The Walrus Was Paul: The Great Beatle Death Clues, Prentice Hall, 1998.

Mark Lewisohn, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, London: Pyramid Books, 1992.

“The Get Back Rehearsals,” Four Parts: The Twickenham Sessions; The Apple Sessions; The Rooftop Concert; and, The Apple Studio Performance.

Peter Doggett, You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After The Breakup, Harper, 2010.

Kenneth Womack, Solid State: The Story of Abbey Road and the End of The Beatles, Cornell University Press, 2019.

Geoff Emerick with Howard Massey, Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of the Beatles, Gotham, 2006.

____________________________

Books at Amazon.com…