Note to Readers: Recent historical research has cast doubt on where, when, and whether the 1947 “arms-around-the-shoulders” moment between Pee Wee Reese and Jackie Robinson, as described below and in many other accounts, actually occurred. Ken Burns in his April 2016 PBS Jackie Robinson film, and others, have challenged the accuracy of the story. — j.d., 3/20/16

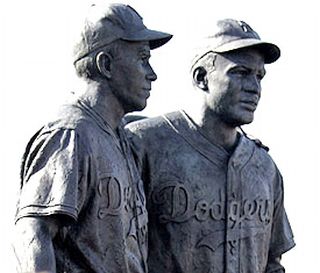

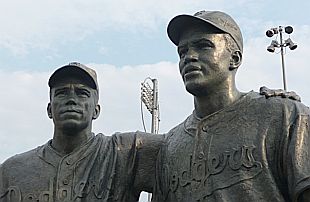

Brooklyn, NY sculpture of Pee Wee Reese left and Jackie Robinson, commemorating Reese’s May 1947 "arm-around-the-shoulders" support of Robinson during racial heckling by fans at a Cincinnati Reds game. Photo: MLB.com.

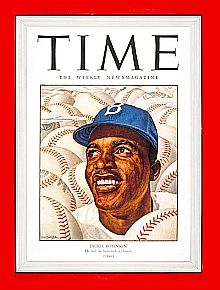

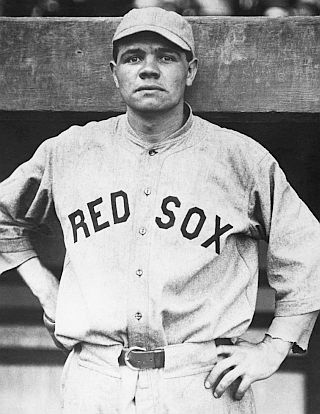

Robinson, however, wasn’t just any player. He was the first African American to play on a professional baseball team. Baseball then was still an all-white affair, as black ballplayers played in the “separate and apart” Negro League, as it was called. Robinson, however, was chosen by Brooklyn Dodgers general manager, Branch Rickey, to be the first black player to play for a professional team in Major League baseball.

Robinson had been signed by the Dodgers in 1945 and had played for the Dodger’s minor league team a year earlier in Montreal, Canada. He had made his major league debut with the Dodgers at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field on April 15th, 1947. So this game in Cincinnati was among the earliest of the Dodgers’ road games that year, with Robinson being introduced for the first time to fans beyond Brooklyn. In Cincinnati that day, however, they were not particularly welcoming of Robinson.

The Pee Wee Reese-Jackie Robinson monument is a work by sculptor William Behrends. Photo, Ted Levin.

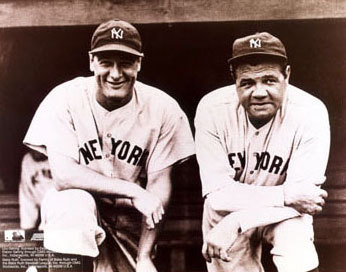

Also taking infield practice that day was Dodger shortstop, Harold “Pee Wee” Reese, a veteran player and team captain. But Reese on this day walked diagonally across the field to join Robinson, where he began a conversation with the rookie and put his arm around Robinson’s shoulders as he spoke with him.

Reese then, according to sportswriter Roger Kahn, “looked into the Cincinnati dugout and the grandstands beyond,” as the slurs and heckling were coming from both Cincinnati ballplayers and fans. Some were shouting out terms like “shoeshine boy” and “snowflake” and worse. Reese, however, did not call out at the taunters or the Cincinnati dugout. But he kept his arm around Robinson’s shoulder while talking to him, which soon helped quiet the crowd and defuse the hostility. It was a moment for many who saw it say they will never forget, as a hush fell over the field and stadium. For Robinson and Reese, the moment became an important bonding experience that helped forge a long friendship. Years later Robinson would tell Roger Kahn: “After Pee Wee came over like that, I never felt alone on a baseball field again.”

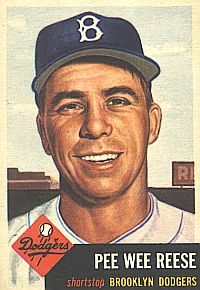

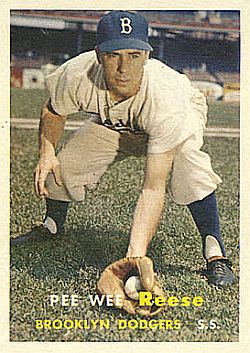

Pee Wee Reese, Brooklyn Dodgers, on a 1953 Topps baseball card.

Reese was still finishing up his World War II military tour in the U.S. Navy in 1946 when Jackie Robinson was signed to the Dodgers’ baseball organization. Robinson would begin his play that year with the Dodgers’ minor league team in Montreal, Canada. But in 1947, when Robinson reported to the main Brooklyn Dodger’s spring training camp, Reese was the first Dodger to walk across the field and shake his hand. “It was the first time I’d ever shaken the hand of a black man,” Reese would later say. “But I was the captain of the team. It was my job, I believed, to greet the new players.”

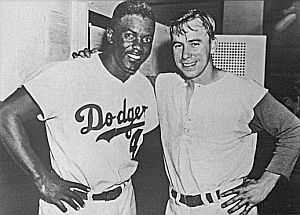

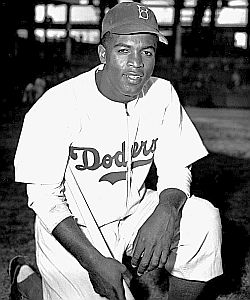

Jackie Robinson, Brooklyn Dodgers.

Jackie Robinson & Brooklyn Dodger’s general manager, Branch Rickey, shown in a 1948 photograph. Click for collector plaque.

Rickey wanted a candidate who had the guts not to strike back. He asked Robinson to promise he would not fight back for his first three seasons – even though he would surely hear every imaginable kind of slur and insult. However, Robinson’s first test at the major league level – he already had a season’s worth of taunts at the minor league level in 1946 – came not from fans, but from his own Brooklyn Dodger teammates.

Jackie Robinson & Pee Wee Reese, circa 1950s.

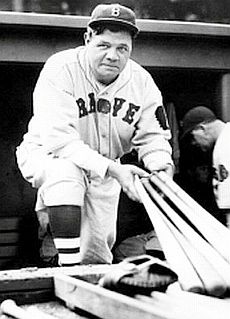

But Pee Wee Reese became one of the most popular players of his day, known among fans and teammates as the “Little Colonel.” Not only was he the Dodgers’ captain in those years, he almost appeared to be their manager on occasion, bringing out the line-up card to the umpires at the start of games, a practice usually reserved for managers.

Brooklyn Dodgers players on opening day, April 15, 1947, from left: John Jorgensen, Pee Wee Reese, Ed Stanky and Jackie Robinson.

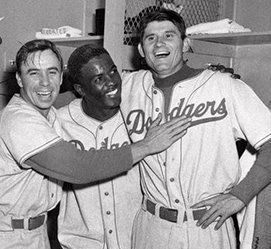

Pee Wee Reese, Jackie Robinson, and pitcher “Preacher” Roe celebrating after beating the New York Yankees in game 3 of the 1952 World Series.

That first year for Robinson, his teammates, and the Dodger organization was a rough time. Reese, who was also Robinson’s roommate when they traveled, did what he could to help buoy Robinson through the worst of insults and hard times. But in the end, it was Robinson’s play that won the day and would gradually win fan support. Still, under great pressure in that first year, Robinson’s play was outstanding, and he won the Rookie of the Year award.

“Thinking about the things that happened,” Reese would later say of Robinson’s ordeal, “I don’t know any other ballplayer who could have done what he did. To be able to hit with everybody yelling at him. He had to block all that out, block out everything but this ball that is coming in at a hundred miles an hour. To do what he did has got to be the most tremendous thing I’ve ever seen in sports.”

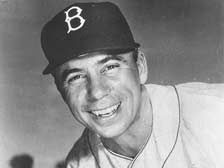

“Pee Wee” Reese

Pee Wee Reese of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

By 1942, Reese made National League All-Star team at age 24. Then with World War II, he went off to serve in the U.S. Navy for two years. Back with the Dodgers in 1946, Reese was named to the National League All-Star team again, a distinction he would win in eight more consecutive seasons.

Pee Wee Reese of the Brooklyn Dodgers, shown on 1957 Topps baseball card.

In 1953 Reese again was an important player in the Dodgers’ National League pennant run, compiling a .271 batting average and scoring 108 runs. The Dodgers went 105–49 that year but again lost the world Series to the Yankees. In 1954, now 36 years old, Reese compiled a .309 batting average. The following year he scored 99 runs as the Dodgers won their first World Series with Reese garnering two RBIs in Game 2 while also making some outstanding defensive plays. By 1957, Reese was playing less as starter, and after moving with the Dodgers to Los Angeles in 1958 as a backup infielder, he retired. In 1959, he coached with the Dodgers, a year they won the World Series. After that, Reese enjoyed a broadcasting career for a time, working with CBS, NBC, and the Cincinnati Reds. He later became director of the college and professional baseball staff at Hillerich & Bradsby, maker of Louisville Slugger bats. Reese was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1984. Reese passed away in 1999. At Reese’s funeral, Joe Black, another African American ballplayer who helped integrate baseball, spoke of how he and others had been moved by Reese’s support for Robinson when the insults were flying:

“…When Pee Wee reached out to Jackie, all of us in the Negro League smiled and said it was the first time that a white guy had accepted us. When I finally got up to Brooklyn, I went to Pee Wee and said, ‘Black people love you. When you touched Jackie, you touched all of us.’ With Pee Wee, it was No. 1 on his uniform and No. 1 in our hearts.”

Jackie Robinson

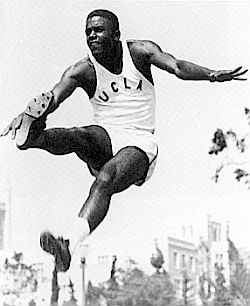

Among other things, Jackie Robinson had been a track star at UCLA in 1940.

Following high school, Robinson attended Pasadena Junior College, where he continued his athletic career excelling in basketball, football, baseball, and track. After junior college, he transferred to UCLA, where he became the school’s first athlete to win varsity letters in four sports: baseball, basketball, football, and track.

In 1939, he was one of four black players on the UCLA football team, a time when mainstream college football had only a few blacks in the game. In 1940, Robinson won the NCAA Outdoor Track & Field Championship long jump event, baseball then being his “worst sport.”

Jackie Robinson in his U.S. Army officer’s uniform, was acquitted in a court martial for a “back-of-the-bus” incident & false charges. Click for photo.

Meanwhile, Branch Rickey of the Brooklyn Dodgers had been searching for a prospective black ball player to help break the color barrier in professional baseball, and in August after meeting with several prospects, he began meeting with Robinson. Satisfied that Robinson would commit to not fighting back, Rickey signed him to a contract of roughly the equivalent of $7,300 a month in today’s money. The deal was formally announced in late October 1945 that Robinson would be playing for the Dodgers’ Montreal Royals minor league team for the 1946 season.

Jackie Robinson at his first minor league game, Jersey City, N.J., April 18, 1946.

In March 1946 the Triple-A Royals were scheduled to play an exhibition against their parent club, the Dodgers. However, both Florida towns of Jacksonville and Sanford refused to allow the game to be played in their parks, citing segregation laws. Daytona Beach, however, agreed, and the game was played on March 17, 1946.

The Dodgers, however, didn’t forget the incident, as the following year they shifted their spring training from Jacksonville, their previous spring training home, to Daytona.

Jackie Robinson at his Major League debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, April 15,1947.

Next came the big leagues. But some of the Dodgers’ players weren’t happy to be playing with a black man, as some had signed a petition saying they would not play. Rickey delegated team manager Leo Durocher to address the problem head on, which he did in a locker room speech.

“I do not care if the guy is yellow or black, or if he has stripes like a … zebra,” he told his players. “I’m the manager of this team, and I say he plays. What’s more, I say he can make us all rich. And if any of you cannot use the money, I will see that you are all traded.”

Example of hate mail Jackie Robinson received, May 20, 1950, Cincinnati, Ohio. Photo: National Baseball Library.

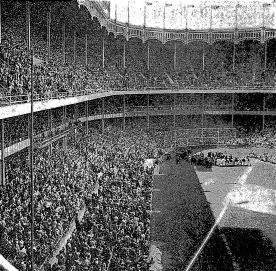

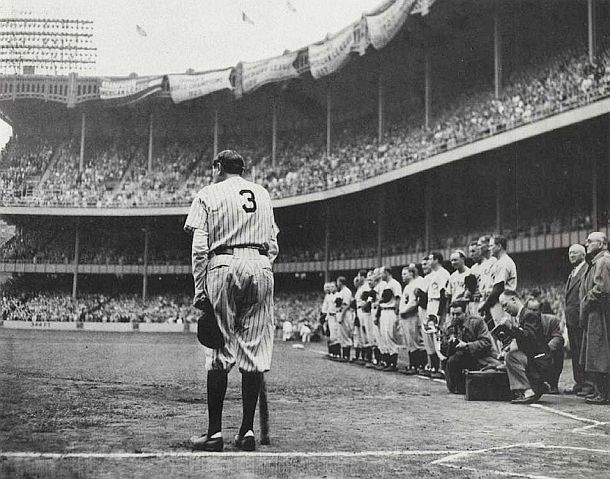

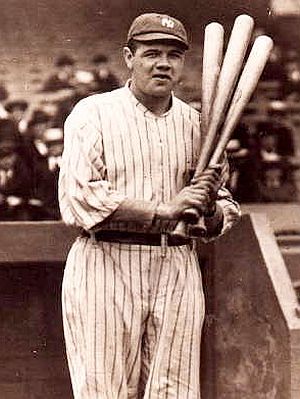

There were also lots of incidents on the road, like that at Crosley Field where Pee Wee Reese interceded. In August 1947 in St. Louis, Cardinals player Enos Slaugher purposely slid high into Robinson at first base, spikes first, slicing open Robinson’s thigh. Still, even with this onslaught of taunts, rough play, and death threats, Robinson finished the 1947 season with a .297 batting average, 125 runs scored, 12 home runs, and a league-leading 29 stolen bases. His performance earned him the inaugural Rookie of the Year Award, then a single award covering both leagues. Robinson’s play that year also helped the Dodgers win the National League Pennant, then meeting the New York Yankees in the 1947 World Series, though losing to the Yankees in seven games. The taunts and threats for Robinson, however, would continue for years.

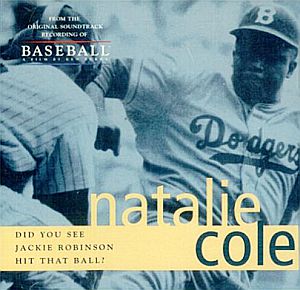

In 1948, Robinson played second base with a .980 fielding average. He hit .296 that year with 22 stolen bases. In one game against the St. Louis Cardinals in late August 1948, Robinson “hit for the cycle,” a rare batting feat of a home run, a triple, a double, and a single in the same game. The Dodgers finished third in the league that year. By this time, other black players had joined professional baseball, including Larry Doby who joined the Cleveland Indians in the American League in July 1947 and Satchel Paige, who also played for Cleveland. The Dodgers, too, had added three additional black players.In 1949, after working with retired Hall-of-Famer and experienced batsman George Sisler, Robinson improved his batting average to.342. He also had 124 runs batted in (RBIs) that year, 122 runs scored, 37 stolen bases, and was second in the league for doubles and triples. Robinson became first black player voted into the All-Star Game that year, and also the first black player to receive the league’s Most Valuable Player (MVP) award. A popular song was also made in Robinson’s honor that year – a song by Buddy Johnson that was also recorded by Count Basie and others – “Did You See Jackie Robinson Hit That Ball?” The song became a pop hit, with the Buddy Johnson version reaching No. 13 on the music charts in August 1949. The Dodgers, meanwhile, won the pennant again, but also lost again to the Yankees in the World Series.

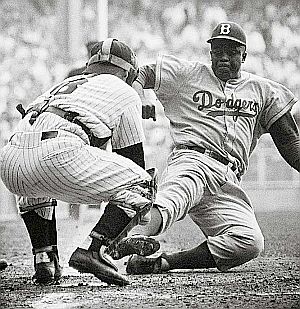

Jackie Robinson, once on base, was always a stealing threat, having very quick feet, a good sense of timing, and smart base running.

Branch Rickey, then with an expired contract and no chance of replacing Walter O’ Malley as Dodger president, cashed out his one-quarter ownership interest in the team and became general manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates.

In 1951, Robinson had another good year, finishing with a .335 batting average, 106 runs scored, and 25 stolen bases. He also again led the National League in double plays made by a second baseman with 137. Robinson kept the Dodgers in contention for the 1951 pennant with a clutch hitting performance in two at bats in an extra inning game that forced a playoff against the New York Giants – that later game ending badly for the Dodgers with the famous Bobby Thomson home run giving the Giant’s the pennant.

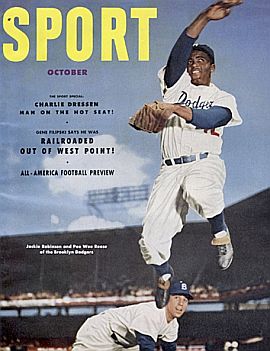

Pee Wee Reese & Jackie Robinson featured on the October 1952 cover of “Sport” magazine turning a defensive “double play” .

By 1953 Robinson began playing other positions, as Jim Gilliam, another black player, took over at second base. Robinson’s hitting, however, was a good as ever, compiling a .329 batting average, scoring 109 runs, and 17 steals. The Dodgers again took the pennant and again lost the World Series to the Yankees, this time in six games.

During the 1953 season, a series of death threats were made on Robinson’s life. Still, on the road, he would speak out and criticize segregated hotels and restaurants that poorly served the Dodger organization, including the five-star Chase Park Hotel in St. Louis, which later changed its practices.

In 1954, Robinson had a .311 batting average, scored 62 runs, and had 7 steals. His best day at the plate that year came on June 17th when he hit two home runs and two doubles.

Jackie Robinson’s steal of home in Game 1 of the 1955 World Series still angers Yogi Berra who claims Robinson was out. Photo: Mark Kauffman/SI. Click for related photo.

Over ten seasons, Jackie Robinson had helped the Dodgers win six National League pennants, taking them to the World Series in each of those years, winning the Series in 1955. He was selected for six consecutive All-Star games from 1949 to 1954, received the inaugural MLB Rookie of the Year award in 1947, and won the National League Most Valuable Player award in 1949. But Jackie Robinson’s career, of course, was marked by much more than his outstanding play; as he became a powerful impetus for, and one of the most important figures in, the American civil rights movement that grew through the 1950s and 1960s.

Pee Wee Reese-Jackie Robinson statue at the entrance of KeySpan Park, Coney Island, Brooklyn, NY. Photo: Ted Levin.

Since then, Jackie Robinson’s life and legacy have since been commemorated on postage stamps and presidential citations; special anniversary commemorations and also having his playing numeral, 42, retired by all Major League baseball teams.

In 1973, his wife Rachel created the Jackie Robinson Foundation, which has since awarded higher education scholarships to more than 1,200 minority students and is also involved in other baseball history and leadership development programs.

In 1999, Time magazine named Robinson among the world’s 100 most influential people of the 20th century, while Sporting News placed him on its list of Baseball’s 100 Greatest Players. He was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal. Yet among all the Jackie Robinson commemorations and honors — and there are many others enumerated elsewhere — the 2005 Reese-Robinson sculpture in Brooklyn commemorating that moment in May 1947 when the two ballplayers made a powerful social statement by simply standing together, remains one of the more interesting and instructive honors, capturing a moment that stands out in baseball as well as the nation’s social history.

The Statues

Reese-Robinson sculpture in Brooklyn sits atop a pedestal with descriptive engraving about the 1947 incident in Cincinnati. Photo Ted Levin.

The genesis of the project came about shortly after Pee Wee Reese’s death in August 1999, with some fans looking for a way to commemorate Reese’s playing career. Stan Isaacs, a columnist with Newsday, suggested that instead of naming a parkway or highway after Reese, that a statue in Brooklyn honoring the famous Reese-Robinson moment in 1947 would be a fitting tribute to Reese. Isaacs’ suggestion was subsequently mentioned during a TV broadcast of a Mets baseball game. Then New York Post writer, Jack Newfield, picked up the idea, writing about it in several columns. By December 1999, then Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani embraced the proposal and a committee was formed study the project. Giuliani became one of the lead donors for the project, making a $10,000 gift after he left office. The project then lapsed for a time following September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center.

Close-up of Pee Wee Reese-Jackie Robinson sculpture. Photo: “Mets Guy in Michigan” website.

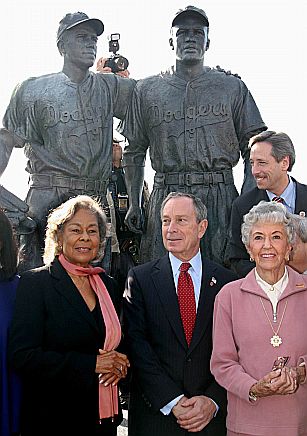

At the dedication ceremony for the Reese-Robinson sculpture in 2005 are, from left: Rachel Robinson, NY Mayor Michael Bloomberg, Dorothy Reese, and NY city councilman, Mike Nelson . Photo: Ted Levin.

“This monument honors Jackie Robinson and Pee Wee Reese: teammates, friends, and men of courage and conviction. Robinson broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball, Reese supported him, and together they made history. In May 1947, on Cincinnati’s Crosley Field, Robinson endured racist taunts, jeers, and death threats that would have broken the spirit of a lesser man. Reese, captain of the Brooklyn Dodgers, walked over to his teammate Robinson and stood by his side, silencing the taunts of the crowd. This simple gesture challenged prejudice and created a powerful and enduring friendship.”

At the dedication ceremony in November 2005, there were a number of speeches given by Mayor Michael Bloomberg, various baseball dignitaries, local officials, and Reese-Robinson family members. They all had good things to say.

“The Reese family is extremely proud to be able to share in the unveiling of this very special statue with the Robinson family,” said Reese’s wife, Dorothy.

“Pee Wee didn’t see Jackie Robinson as a symbol, and, after a while, he didn’t see color. He merely saw Jackie as a human being, a wonderful individual who happened to be a great ball player. My husband had many wonderful moments in his life, but if he were alive today, I know he’d say this honor was among the greatest in his life. I share in that sentiment.”

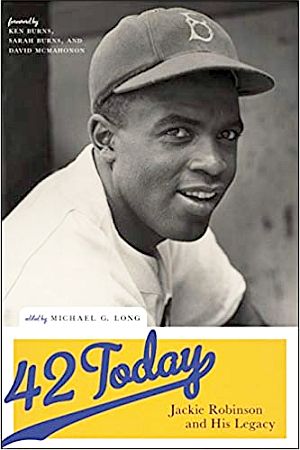

Michael Long’s 2021 book, “42 Today: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy,” includes 13 essays from sportswriters, cultural critics, and scholars on Robinson’s legacies on civil rights, sports, nonviolence and more. 256 pp, NYU Press. Click for copy.

“When Pee Wee Reese threw his arm around Jackie Robinson’s shoulder in this legendary gesture of support and friendship,” said Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz, “they showed America and the world that racial discrimination is unacceptable. Pee Wee and Jackie showed the courage to stand up for equality in the face of adversity, which we call the Brooklyn attitude. It is a moment in sports, and history that deserves to be preserved forever here in Brooklyn, proud home to everyone from everywhere.”

Jackie Robinson’s wife, Rachel, also spoke at the ceremony. “The Robinson Family is very proud to have the historic relationship between Jackie Robinson and Pee Wee Reese memorialized in the statue being dedicated at KeySpan Park,” she said. “We hope that it will become a source of inspiration for all who view it, and a powerful reminder that teamwork underlies all social progress.”

See also at this website, “A Season of Hurt: Aaron Chasing Ruth,” about the career of Milwaukee /Atlanta Braves star, Henry “Hank” Aaron, including the racial torment he endured during 1972-74 as he pursued and surpassed, Babe Ruth’s career home run mark.

Additional baseball history at this website can be found at “Baseball Stories, 1900s-2000s,” a topics page with links to 14 baseball-related stories. For sports generally, see the “Annals of Sport” category page.

Other “statue-related” stories at this website include, for example: “RFK in Brooklyn,” “The Rocky Statue” (at the Philadelphia Art Museum), and “The Jackson Statues” (Michael Jackson). Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle.

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 29 June 2011

Last Update: 21 March 2021

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Reese & Robbie, 1945-2005,”

PopHistoryDig.com, June 29, 2011.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

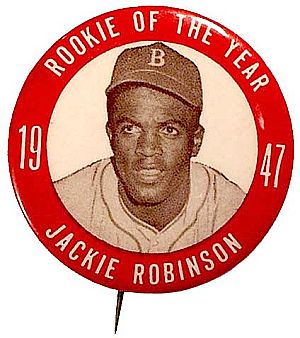

The late 1940s-early 1950s were the heyday of "stadium pins” or “pinbacks,” produced for sale at stadium concession stands to depict and support favorite players; collectables today. Jackie Robinson is shown in this 1947 Rookie-of-the-Year pin. According to one source, no player aside from Babe Ruth has been the subject of more pins than Jackie Robinson. |

Newspaper coverage of Jackie Robinson’s major league debut by the black-owned “Pittsburgh Courier” (Wash., D.C. edition), Saturday, April 19, 1947. |

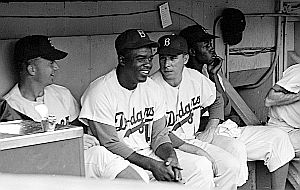

Sept 1953: Jackie Robinson & Pee Wee Reese, center, in the Brooklyn Dodgers dugout. Look Collection, U.S. Library of Congress. |

Pee Wee Reese & Jackie Robinson turning a double play during March 1950 spring training in Vero Beach, FL. Photo Phil Sandlin, AP. |

Tim Cohane, “A Branch Grows in Brooklyn,” Look, March 19, 1946, p. 70.

“Sport: Rookie of the Year,” Time (cover story) Monday, September 22, 1947.

“Jackie Robinson’s First Year As a Dodger,” Look, January 6, 1948.

Jackie Robinson, “My Future,” Look, January 22, 1957.

Red Barber, 1947, When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball, Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1982.

Roger Kahn, The Boys of Summer, New York: Perennial Library, 1987.

Maury Allen, Jackie Robinson: A Life Remembered, New York: F. Watts, 1987.

Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns, Baseball: An Illustrated History, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994, pp. 285-300.

Ben Couch, “Robinson, Reese Now Together Forever; Statue of Former Brooklyn Dodgers Teammates is Unveiled,” MLB.com, November 1, 2005.

Rachel Robinson and Lee Daniels, Jackie Robinson: An Intimate Portrait, New York: Abrams, 1996.

Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy, New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson,” New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997, 448pp.

“Pee Wee Reese,” Wikipedia.org.

“Baseball, the Color Line, and Jackie Robinson, “Online Exhibit, Library of Congress.

“Jackie Robinson Timeline,”MLB.com.

Ira Berkow, Sports of the Times, “Standing Beside Jackie Robinson, Reese Helped Change Baseball,” New York Times, March 31, 1997

“Rachel Robinson Recalls How the Late Pee Wee Reese Helped Jackie Robinson Integrate Baseball,” Jet Magazine, September 13, 1999.

Press Release, “Mayor Bloomberg and Brooklyn Borough President Markowitz Unveil Jackie Robinson and Pee Wee Reese Monument,” Office of the Mayor, New York, NY, November 1, 2005.

Ted Levin Photos, “A Monument for Tolerance: Jackie Robinson and Pee Wee Reese,” pBase.com, November 2005.

“Keyspan Park,” Mets Guy In Michigan, website.

Scott Simon, Jackie Robinson and the Integration of Baseball,

Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2007, 176pp.

“Jackie Robinson,” Wikipedia.org.

“Jackie Robinson and Dr. Martin Luther King: They Changed America,” Padre steve’s World, January 18, 2010

“The Glory Days: New York Baseball, 1947-1957,”Exhibit, Museum of the City of New York.

“Remembering Jackie Robinson, 1946,” MiLB.com, 2006.

Roger Kahn, Letter to the Editor, “The Day Jackie Robinson Was Embraced,” New York Times, April 21, 2007.

Jonathan Eig, Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007, 336 pp.

Barry M. Bloom, “Jackie Robinson: Gone But Not Forgotten; Dodgers Legend Continued to Be a Force after His Playing Days,” MLB.com, June 4, 2007.

“Jackie Robinson: An American Icon,” DefinitiveTouch.com, October 31, 2009.

Re: Reese-Robinson “arms-around-the-shoulders” moment:

“Robinson Movie and Incident at Crosley Field,” From The Reds Hall (The Official Blog of the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame and Museum), April 12, 2013.

Joe Posnanski, “The Embrace,” NBCsports .com.

Brian Cronin, “Did Reese Really Embrace Robinson in ’47?,” ESPN.com, April 15, 2013.