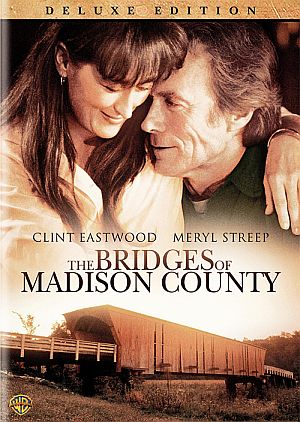

Cover of deluxe edition DVD of the 1995 film issued by Warner Home Video in June 2008. Click for video or DVD.

The two strangers from different worlds — Robert Kincaid, the free-roaming, globe-trotting photographer, and Francesca Johnson, the Iowa-bound farm wife — strike up an intense, short-lived love affair. However, reality and responsibility soon intrude and the affair ends. The two lovers, torn by separation, return to their previous lives with thoughts of what might have been.

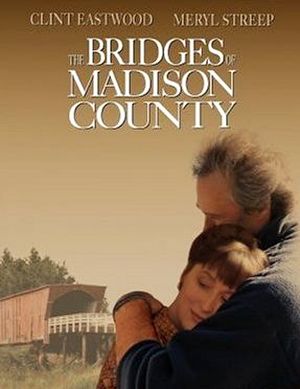

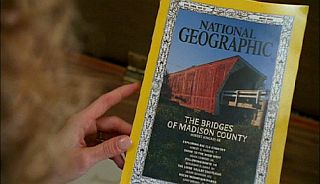

The Bridges of Madison County, set in mid-1960s Iowa with its rustic covered bridges, tells their story. The book became a word-of-mouth sensation and dominated bestseller lists all across America. It was followed in 1995 by a well-received Hollywood film with Meryl Streep and Clint Eastwood in the lead roles.

Throughout the early- and mid-1990s, there was notable TV and radio coverage of the story, the book, and the film, as well as marketing of related books, music, photography, and Iowa tourism. How this story swept over America is quite a tale in its own right. First, a look at the book’s author and then its storyline, told below with screen shots from the 1995 film.

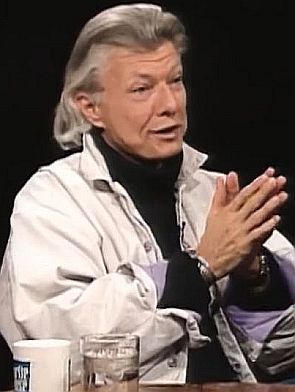

Robert James Waller on The Charlie Rose Show, February 1993, after his book was No. 1 on the NY Times bestseller list. |

The Author

The Bridges of Madison County came from a somewhat unexpected and unknown author — a Midwest born and bred economics professor named Robert James Waller.

Born in 1939, Waller grew up in Rockford, Iowa. He received both his BA (1962) and MA (1964) from the University of Northern Iowa (UNI), where he also met his wife.

By 1968 he added a Ph.D in business from Indiana University. Later that year, returning to UNI, he became a professor of economics and business management, rising to dean of the College of Business there in 1980.

Although active in his academic field, Waller also had interests in music and writing. In 1988, he published a collection of essays with Iowa State University Press, followed later by three more collections. He was also something of a photographer, and one day he was out taking pictures of covered bridges in Madison County, Iowa. That’s when he first got the idea for his book.

“The actual book was written after I’d been down photographing the bridges…,” Waller explained during a 1993 interview on The Charlie Rose Show.

“Did it come to you in a moment?,” asked Rose.

“Absolutely,” answered Waller. “It struck me; it came to me in a three-hour drive across the flatlands of Iowa in my truck” (on his way home). Also figuring into Waller’s inspiration was a line from a song he had written, which he describes as, “I know you have your own dreams too, Francesca.” The name Robert Kincaid also came to him as he drove home.

When Waller arrived home he fired up his computer and began writing in a non-stop mode, he explained, “for two weeks, sleeping two or three hours a night….”

Rose interjects, “and it flowed?”

“Oh, it was given to me,” said Waller. “I never knew where the next line was coming from, but when I got to it, it was there. And I know that’s hard, I’m sure, for people to believe. [But] it’s true…”

What Waller had created was the story of an Italian WWII bride named Francesca brought back to middle America to live the life of an Iowa farm wife; a woman committed to her marriage and family until one day when a stranger happens into her life.

The Story

Robert Kincaid is 52 years old when he arrives in Iowa on a professional photographic assignment. It is August 1965. He has come to Iowa from his walk-up apartment in Bellingham, Washington to take pictures of historic covered bridges for National Geographic. There are seven bridges he will photograph, all in Madison County, Iowa.

Kincaid is an independent sort who has been around. He has served in the military, and was once married for five years to an aspiring folk singer. However, his time on the road put a strain on that marriage. Still, at middle age, while he has not given up on the prospect of a longer-term relationship, he has not gone out of his way to look for one.

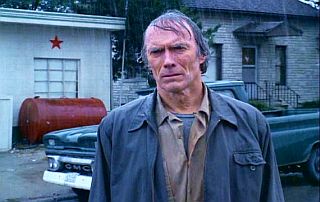

Kincaid has a weathered, handsome look physically. He features himself as something of a contrarian, and is not always comfortable with the ways of the modern world. He also has another side; a bit softer, more creative, quoting famous poets now and then.

Francesca Johnson is a 45 year-old farm wife, married to Richard Johnson, a good but unromantic Iowa farm man who she met in her native Italy during World War II. Johnson made Francesca his war bride and she consented because of his kindness and the promise of America.

Francesca is filling the traditional role of mother and homemaker, focused on husband and family. Yet she is also educated, has a degree in comparative literature, and has done some teaching at the local high school. By 1965, Francesca and Richard have two teenage kids. She dearly loves her family, but is often isolated in her simple, mundane life, lacking intellectual engagement.

So, in August 1965, with her family away at the Illinois State Fair for several days, her life suddenly takes a new turn when Robert Kincaid pulls his pickup truck into her farm driveway. He has stopped to ask for directions to the Roseman covered bridge .

To The Bridge

Since the rural roads to the Roseman Bridge are not clearly marked, and Francesca has difficulty explaining how to get there, she offers to show him the way, riding along in his pick-up truck. When they arrive at Roseman bridge, she watches him work as he shoots the bridge. Kincaid takes various shots of the bridge, some at a distance. However, he is losing the light he needs for certain shots and will return the next day to shoot more.

When they arrive back at Francesca’s homeplace, she asks him in for a glass of iced tea, and after a bit of conversation, invites him to stay for dinner. In her farm kitchen, he helps her prepare vegetables for the meal, they share a few beers from his cooler, and exchange their life stories. After dinner they take a short walk in the pasture, followed by coffee and brandy back in the kitchen.

The evening ends as Kincaid takes his leave, needing to rise early for the next day’s shoot. But something in Francesca has been stirred.

Francesca’s Note

Knowing that Kincaid will return to the bridge the next day, she drives there later that night and tacks up a note where she knows Kincaid will find it. It is an invitation to dinner the following evening.

At dinner the next evening at her home, Robert and Francesca realize they have fallen in love, as their affair begins. During their four days together, they have much intimacy and tender conversation. He asks her to come away with him, but she cannot because of her sense of responsibility to her husband and family. Robert still wants her to leave with him and she actually packs her bags to go with him at one point. But in the end, she cannot abandon her husband and her two children. She explains that she could never bring such pain and humiliation to her family. She knows they would not survive the gossip and censure that would certainly follow such an event in the conservative farming community.

Kincaid reluctantly leaves to continue his life of travel and photography, but Francesca is always on his mind and he on hers. They have only a couple of written contacts over the years, but never meet again, each holding fast to memories of their affair. During their four days together, Francesca gave Robert an ornate, hand-wrought medallion with her name etched on the back.

Years Later

After Kincaid has died, a package reaches Francesca that contains his cameras, the medallion she had given him, the old note she had tacked to the bridge, and other items. There is also an explanatory letter that informs Francesca that Kincaid has passed away. She also learns that his cremated remains were scattered at the Roseman Bridge.

Francesca’s own husband by this time, Richard — whom she tended in late-life illness — has passed away, and she lives out her days alone remembering her time with Robert. One day, a neighbor finds Francesca dead, slumped over her kitchen table. She was 69. Francesca, however, has left instructions requesting that she be cremated and her ashes scattered at Roseman Bridge. This is something of a puzzle to her two grown and married children, since the family plan had been to bury her alongside their father.

In the book, the story is set up with an opening preface and frame of reference set in 1989, shortly after Francesca’s death. Her passing has brought her two grown children back to the Iowa farm who later discover the details of their mother’s affair. For Francesca has left them an explanatory letter, along with her journals and a box full of Robert Kincaid mementos. In the book’s preface, the two grown children have contacted the story’s narrator, a writer, asking him to tell their mother’s special love story, which then becomes the novel.

Waller’s Book

Back in the real Iowa, meanwhile, before the story ever became a film or a book, author Robert Waller was left in July-August 1990 with a completed manuscript and not much more. In fact, he would later say he was not overly enamored with the idea of publishing it as a book, even though several of his local trusted readers had really liked the story and encouraged him to publish. During a later interview on The Charlie Rose Show, Waller said he was content to have written it just for himself and a few friends as something he felt he had to do. He also noted that at the time he was fairly content as a full professor, was completing a book on economic philosophy, and was not particularly thrilled by the prospect of the New York publishing scene and book marketing. However, a friend at Iowa State University press who had published some of his collected essays helped Waller move toward publication. And gradually the right connections and referrals were made and a literary agent in New York was engaged.

After a couple of rejections in New York, Warner Books, part of the Time-Warner Corporation, offered to publish Waller’s book. It was September 1990. As later recounted in David Comfort’s book, An Insider’s Guide to Publishing, Warner offered a $32,000 advance. Later that year, Waller received some additional good news: that Steven Spielberg was interested in buying the book’s movie rights for his film unit, Amblin Entertainment. This was long before before the book’s publication. Still, a film on the book was no sure thing.Steven Spielberg optioned the movie rights 8 months before the book’s publi- cation. Hundreds of books are acquired every year for films, but very few ever make it to the big screen. Word was, however, that some of Spielberg’s people — namely Kathleen Kennedy, then president at Amblin — liked the storyline involving an older couple.

Kennedy had read the book when it was in galley form before its publication. “I loved it,” she would say in one interview, “and I thought that Waller had tapped into something universal.” According to Newsweek, Spielberg told Kennedy, “If you love it, buy it.” So Kennedy optioned the rights for $25,000 eight months before the book was published and later paid 10 times that amount for the film rights. “This was like catching a tidal wave that nobody saw coming,” Lucy Fisher, a Warner Brothers v.p. told Newsweek.

Meanwhile, in April 1992, the first hardback copies of The Bridges of Madison County went to market. The initial print run by Warner was a generous 29,000 copies for a first-time novel. However, the book’s initial reception was not great. Some early reviews in 1992 were not very good. Kirkus Reviews noted in January 1992: “Here’s a Hallmark card for all those who have loved and lost: a mushy memorial to a brief encounter in the Midwest.” The Kirkus reviewer also commented, somewhat skeptically, on the book’s sales prospects: “For as fake and pretentious as it is, this first novel is based on hard-nosed commercial calculations. The publisher, promising a big push, clearly expects its silly goose to lay a golden egg, and, who knows, maybe it will.” Library Journal in March 1992 charged the book had a “contrived, unrealistic dialog,” while the The Washington Post in early April called the storyline “trite.” But other reviewers were kinder. Publishers Weekly in April 1992 called the book “quietly powerful and thoroughly credible,” adding that “scenes between the lovers are movingly evoked…” Entertainment Weekly in June 1992 noted the story “seems likely to melt all but the most determined cynics…”

|

“He Noticed All He could have walked out on this earlier, could still walk. Rationality shrieked at him. “Let it go, Kincaid, get back on the road. Shoot the bridges, go to India. Stop in Bangkok on the way and look up the silk merchant’s daughter who knows every ecstatic secret the old ways can teach. Swim naked with her at dawn in jungle pools and listen to her scream as you turn her inside out at twilight. Let go of this”- the voice was hissing now – “it’s outrunning you.” But the slow street tango had begun. Somewhere it played; he could hear it, an old accordion. It was far back, or far ahead, he couldn’t be sure. Yet it moved toward him steadily. And the sound of it blurred his criteria and funneled his own alternatives toward unity. Inexorably it did that, until there was nowhere left to go, except toward Francesca Johnson. |

Then in mid-summer of 1992, something else started to happen. People who had read the book began returning to stores to buy multiple copies. The book was being given out as a gift and as a pass-along to friends and family. By July 1992, the trade press was reporting that independent book stores were selling the book at quite high numbers — partly the result of a campaign by Warner Books for booksellers to personally sell the book directly to their customers. Stores in several states began reporting higher than normal sales.

More favorable reviews were also appearing around the country. Through the summer and fall of 1992, favorable-to-glowing reviews and/or comment appeared in various newspapers and magazines. The Bridges of Madison County was also beginning to show up on the book industry’s bestseller lists.

Not long thereafter, on August 16, 1992, it made its first appearance on the New York Times bestseller list at No.12 — directly behind Danielle Steel’s Jewels at No. 11. Among the Times‘ top-selling titles that week were: No. 1, Gerald’s Game by Stephen King; No. 2. Waiting to Exhale by Terry McMillan; and No. 3, The Pelican Brief by John Grisham.

After hitting the Times list, Bridges and Waller began to receive a bit more media attention, including some national radio and TV-talk shows in early 1993. But reader pass-along was still at work as well.

Among the reviews of Bridges noted at the University of Virginia’s archive of 20th Century American Bestsellers, is one by Charles Champlin, writing in the January 17, 1993 edition of the Los Angeles Times Book Review. Champlin described the book as a “sleeper…a nice little book that takes off slowly without benefit of splashy advertising, book-club promotion, or a flood of rave reviews, but that ends up on the best-seller list the old fashioned way — because readers fall in love with it and tell their friends.” And that’s exactly what had happened with Bridges.

Word-of-mouth sales and sales by independent book stores were believed to have propelled the book to best-seller status. By month’s end January 1993, Bridges rose to No.1 on the New York Times list for the first time.By month’s end, January 1993, The Bridges of Madi-son County was No. 1 on the New York Times best sellers list.

“This was a book that we independent bookstores sold,” later explained Dee Peeler, head buyer for the book department at Greetings & Readings in Towson, Maryland, speaking to a Baltimore Sun reporter in August 1993.

She estimated her store by then had sold about 1,000 copies of Bridges: “We read it, we loved it, and we pushed it to our readers. Then they loved it and told their friends. … “It’s just a beautiful little book, and it’s very, very moving — unusual in this day of so much cynicism … In 15 years at this store, I’ve never seen a book quite like it. There have been a lot of best-selling books that have done extremely well, but this is one of a kind.” Still, there was a lot more upside ahead for The Bridges of Madison County. The best-selling reign of this book was just beginning.

The Oprah Effect

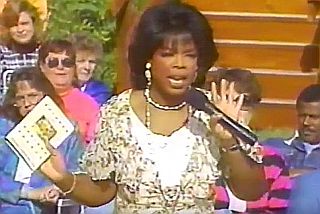

May 21, 1993. Oprah Winfrey touting "Bridges" book on special broadcast of her popular TV talk show in Winterset, Iowa.

The Oprah TV episode from Iowa (found today on YouTube.com and other video postings) was entitled “Bridge of Love,” and it featured the book, its author, and other guests. At the outset, with an audience of a few hundred around her in the outdoor setting, Winfrey called Bridges her “favorite book of the year… one of the most romantic, stirring tales of true love I’ve ever read.” Oprah admitted to crying when she read the book, said she had recommended it to many people, including her best friend, Gayle King, who appeared later in a separate studio segment, also admitting that she cried while reading the book.

Most of Oprah’s show was taken up with engaging her guests, mostly couples, in conversations about their “real-life love affairs.” During some of these segments, she referenced passages from Bridges. Waller and his wife, Georgia Ann, also appeared, but late in the show, and only briefly. On the Iowa TV special, Oprah called The Bridges of Madison County her “favorite book of the year.” Oprah interviewed Waller about the book, and also heard from Georgia Ann, who was among the first to read it, saying she knew the story was special. At the end of Waller’s interview with Oprah, he sang a portion of one or his ballads from a forthcoming album of songs, The Ballads of Madison County, later issued on Atlantic Records. On the show, Winfrey thanked Waller for writing the book, calling it “a gift to the country,” and said the reason they were doing the show in Iowa was to share the story with the nation. At this point in Oprah’s career, she had yet to form her Oprah Book Club, which would in later years have an important impact on particular titles she mentioned or endorsed. Still, club or not, Oprah’s blessing for Bridges was a huge boost — an additional 250,000 copies by some counts — even though the book was already a solid bestseller and had been at No. 1 or No. 2 on the New York Times bestsellers list for over five months.

May 21, 1993. Oprah Winfrey, in Iowa, interviewing Robert Waller, author of best-selling book, "The Bridges of Madison County".

Riki Altman of Books of Wellington, in Port Arthur, Texas told the Associated Press in August 1993 that most buyers of Bridges there came by way of the Oprah show. “We’ve sold tons…They love the book… They’re buying it for friends.” Likewise, Penny Kudyba of Brentano’s in The Gardens Mall, also in Texas, attributed many of her sales to Oprah as well.

Oprah’s show helped propel the book even more into popular discourse, adding to its luster. Indeed, following Oprah, more publicity and marketing came for the book as well. National TV networks featured the rise of the book or came to Iowa to shoot the bridges and/or the burgeoning tourist scene there.

And while Oprah was indeed a major help in mid-1993 to the book’s continued success, according to David Comfort, author of An Insider’s Guide to Publishing, the star behind the scenes in the marketing of Bridges, and a key defender of the book, was Warner Books editor, Maureen Egen:

…When chain [book stores] showed no interest in stocking the novel, Ms. Egen sent out 4,000 advance copies to independent sellers, along with a personal letter urging each to “hand sell” the title, and offering “co-opt money” to those who did so. Due to her tireless marketing, Barnes & Noble and Waldenbooks offered Valentine’s specials for the romance, and sales went stratospheric after Oprah called “Bridges her ‘favorite book of the year,’ ‘a gift to the country,’ and confessed that it made her cry. When Bridges won the 1993 American Booksellers Book of the Year Award as well as the New York Library’s Literary Lion Award, a lively debate arose as to whether it was “literature,” as Egen insisted, or “an insipid, fatuous, mealy-mouthed third-rate soap opera,” as the Chicago Tribune’s reviewer Jon Margolis asserted. But to the industry bookies the argument was moot since the dark horse romance went on to sell 50 million copies…

Critique & Backlash

July 26, 1993. New York Times Magazine full-page critique of "Bridges" from The Times' drama critic, Frank Rich.

Despite the huge popularity of The Bridges of Madison County, the book had its share of critics. A literary backlash had begun among some, debating whether the book should be called literature or pulp romance. One review in the Los Angeles Times would charge that Waller wrote “at times, like a Harlequineer.”

But two reviews that appeared in the New York Times, coming after the book had risen to No. 1 on the bestseller list, hit especially hard. The first, in March 1993, appeared in The New York York Times Book Review by Eils Lotozo, who wrote, for example:

“…Waller depicts their mating dance in plodding detail, but he fails to develop them as believable characters. Instead, we get a lot of quasi-mystical business about the shaman-like photographer who overwhelms the shy, bookish Francesca with his sheer emotional and physical power.”

Then came a second New York Times review, this one in the Sunday New York Times Magazine on July 26, 1993 by drama critic Frank Rich. This review appeared in a full page “End Paper” section of the magazine and was titled “One Week Stand”(shown above left). Rich first had some fun with Waller’s sometimes over-the-top macho descriptions of Kincaid, noting: “Waller devotes separate, scattered passages to his hero’s shoulder muscles, chest muscles, forearm muscles and thigh muscles…” But this was just prelude to Rich’s more central point as he ventured into more weighty social-cultural territory — that Bridges was contributing to the subjugation of women. “In Bridges,” observed Rich, “romance is a one-week stand, unconnected to any relationship or responsibilities. After it’s over, sexy cowboys can move on but women must return to the servitude of dreary domesticity.” And not surprisingly, Rich also took issue with Oprah Winfrey’s contention two months earlier that the book was a “gift to the country.” Although Bridges came under withering attack in some corners, the criti- cism had little apparent effect on the book’s con- tinuing popularity.

Rich wasn’t the only one who called the book out for its portrayal of women. Pauli Carnes, a female reviewer writing freelance for the Los Angeles Times in April 1993, called Waller’s book “porn for yuppie women.” The book, to her, was an insult to women and also demeaned normal marriages. “The Bridges of Madison County,” she wrote at the end of her review, “is not beautiful and touching. It is the story of life wasted.”

But it wasn’t just reviewers who found the stuck-at-home, vulnerable framing of Francesca offensive. “I thought it was one of the worst-written books I ever read,” said Christy Macy in August 1993, then a speech writer for Baltimore Mayor Kurt Schmoke. She was being interviewed on the book by the Baltimore Sun. “Not only did it have paragraphs of whole conversation in ways that people don’t talk, but it’s a terribly sexist book. “Kincaid at least had a life, and was a romantic character. She [Franceca] had no life. That really offended me.”

Little of this critique, however, either from reviewers or unhappy readers, appeared to have much effect on the book’s mid-1990s popularity or sales. The Bridges of Madison County continued to ride high on bestsellers lists.

With Waller’s book nearing its one-year occupation of the New York Times list, for example, another reporter for the Times, Sarah Lyall, noted of Bridges as of July 28, 1993: “It is currently standing firm at No. 1, staring down at books by John le Carre, Robert Ludlum, Scott Turow and John Grisham.” Lyall wondered how a book that was so dismissed and derided by respected reviewers could be doing so well. The answer, according to “armies of Bridges zealots,” she explained, was that “New York is filled with cultural snobs who just don’t understand the appeal of a book about an extramarital affair that doesn’t break up a marriage.” Lyall also noted that Warner Books was then reporting the book was selling 150,000 copies a week at book stores. By late August 1993, Bridges had sold 3 million copies.

|

More Waller

Once Bridges began scaling bestseller lists, Robert James Waller became something of a hot property. By mid-1992, in fact, he had already signed another deal with Warner to produce more books, which he then began writing. There were also two audio books issued for Bridges in 1993, one in Waller’s voice and a second using various celebrity voices.

Atlantic Records, meanwhile, a Warner subsidiary, released an album of original and cover songs by Waller, as he had noted during The Oprah Winfrey Show. Titled The Ballads of Madison County, the CD included cover art similar to the book’s, a lyric booklet, and liner notes by Waller. The CD, however, did not do well, and that cooled Atlantic’s interest in further Waller music.

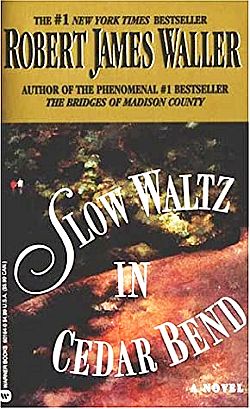

However, Waller’s second book for Warner – Slow Waltz in Cedar Bend (with an initial print run of 1.5 million copies according to the Los Angeles Times) – did quite well. The featured player in Slow Waltz is Michael Tillman, a tenured economics professor, free spirit, and academic maverick who strikes up an affair with Jellie Braden, the wife of another faculty member. Within a year, their love intensifies, but Jellie has a deep secret, runs off to India, and Tillman follows… Completed in August 1993, Slow Waltz debuted at No.2 on the New York Times list in November 1993, right behind Bridges. In fact the two books would stay at No.1 and No.2 for nearly three months.

By mid-April 1994, a third Waller book, Old Songs in a New Café, a collection of essays, was also published by Warner. This one also appeared on the Times bestseller list, but in the nonfiction category. So, by May 1st, 1994, Waller had three books appearing on New York Times bestseller lists. Another Waller book in 1994 — a tear-out book of photo postcards, titled Images: Photographs by the Author of The Bridges of Madison County. Through all of this, however, Bridges was still the main attraction, and still selling briskly through 1994. Yet more action for Bridges was on the way, now shifting to the cinema.

The next day on the bridge, after Francesca has invited Kincaid for a second dinner, he turns his camera on her. |

Back at the farmhouse, before dinner that evening, Francesca is thinking about Kincaid as she takes a bath. |

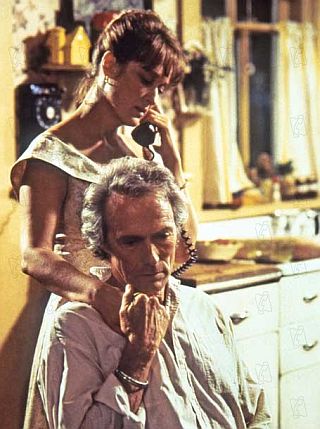

In their "first touch” scene, with Francesca in her new dress, she places her hand on Kincaid’s shoulder as she takes a phone call. |

As the kitchen radio plays a sultry jazz tune, Francesca & Robert share a long, slow dance as they move to consummate their passion. |

Later in the film, Robert and Francesca share a bath. |

In a park away from the farming community, Robert and Francesca anguish over their future. |

Hollywood Film

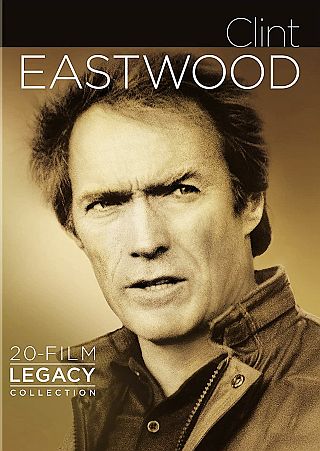

The film version of The Bridges of Madison County, based on the novel by Waller, became a joint project of Amblin Entertainment, Malpaso Productions (Clint Eastwood’s company), and Warner Brothers. The film — though it had some production snags and a few tries at the film script — was produced and directed by Clint Eastwood with Kathleen Kennedy as co-producer. It was filmed in Winterset, Iowa in late summer 1994, cost about $22 million to make, and was released to movie theaters in mid-June 1995. On its opening weekend, it was No. 2 at the box office. It would go on to gross some $182 million worldwide.

The film added some elements that weren’t in the book, such as bringing Francesca’s two adult children into the film more. The movie opens, in fact, with her grown children returning to the farm after she dies to deal with her estate and the discovery of her journals, as the story is told in flashback (see related photos below in Sources). The film also includes a new character, a woman in town; an outcast for having had an affair whom Francesca befriends. The movie version also shifts the story more to Francesca while toning down some of the book’s more macho Kincaid moments. Also added is the “angry breakfast scene” between Francesca and Kincaid as Francesca begins to feel the tug of her responsibilities to family while resenting Kincaid’s freedom.

In the casting for Francesca, according to Entertainment Weekly and other sources, a number of actresses were said to be in the running, among them: Isabella Rossellini, Cher, Anjelica Huston, Jessica Lange, Mary McDonnell, and others. But Eastwood had advocated Meryl Streep from the beginning. For the Kincaid role, Robert Redford had been considered before Eastwood got the role. Meryl Streep, meanwhile, would be nominated for, but did not win, an Academy Award for her role as Francesca. Streep was also a runner-up for best actress of 1995 in voting by the National Society of Film Critics.

The reviews for the film were quite favorable, often more laudatory than those for the book. Variety called the film “…A handsomely crafted, beautifully acted adult love story,” adding, “[Streep] has never been so warm, earthy and spontaneous…” The Chicago Sun-Times review of June 2, 1995 found the film “…Deeply moving.” USA Today gave it 3.5 of 4 stars. Entertainment Weekly of June 9, 1995, wrote: “…Touching in a delicate, almost lyrical way. It’s a wonderful surprise — an honest weeper for adults… Rating: A.”

In his June 1995 film review, Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times noted somewhat diplomatically of the book, though focusing on its central worth: “Its prose is not distinguished, but its story is compelling.” Indeed, in some ways, the film redeems the book, and helps make its central idea and storyline more viable and durable. This is a point other critics made in one form or another.

Janet Maslin of The New York Times praised the script writing and Eastwood’s directing, especially for moving the film away from some of the book’s excesses. “The movie has leanness and surprising decency…,” she wrote.

Chauncey Mabe of the Sun-Sentinel in south Florida, noted in his June 1995 review, that the film was more taut and realistic than the book. He also praised screenwriter Richard LaGravenese, “who has taken Waller’s original idea, filled it with intelligence and genuine romance, deflated its ‘last cowboy’ macho bombast, and lent it a brilliant structure that brings out strengths hidden in the book.” He also added that moving the central focus in the film from Kincaid to Francesca was “one of the smartest things Eastwood and LaGravenese” did with the film.

Not least, however was the acting of Streep and Eastwood. Robert Ebert said that Eastwood and Streep had made the book “into a wonderful movie love story.” Jonathan Rosenbaum, in his June 13, 1995 review for The Chicago Reader noted: “…As long as these two are on-screen one can forget the treacle that brought them there…”

Film editor, Joe Cox, in a later documentary on the film said: “I think the film was so successful because of the chemistry between Meryl and Clint. On camera there was just this, ‘Wow!’ I mean you could feel these two strangers coming together for that moment…” Amblin producer Kathleen Kennedy agreed: “It was instant. Clint and Meryl were what you always look for in a romance. They had that chemistry on film. You just instantly believe that these two people were deeply in love with one another.”

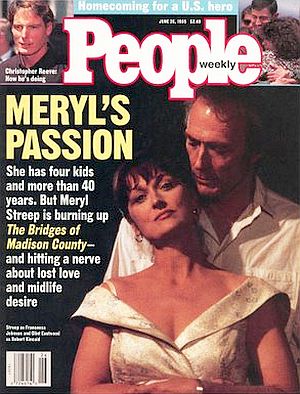

June 1995: "People" magazine cover story on Meryl Streep & "Bridges of Madison County" film.

…The tale that inspires either swooning or lampooning has obviously touched a neglected nerve. It taps into the yearnings of over-40 Americans–a group that now makes up 36 percent of all movie-ticket buyers. Aging boomers are wondering if life could have offered more than the everyday details of kids, a job, iced tea on a hot day. And yet maybe most appealing is the saintlike renunciation of wild passion when it does come along. …Francesca decides she cannot leave her family to ride off with Kincaid. It’s great lovemaking without consequences–no double suicide, no jealous husband blasting into the bedroom, no disruptions of the routine.

Francesca…chooses to go on with her conventional life. She experienced the love of her life. Now she has a brown-sugar meat loaf to make. In fact, the message is, it’s OK to make meat loaf–it’s even the noble choice. ‘That she can feel such passion and then opt for an empty-shell marriage is really reassuring to many people,’ says Harriet Lerner, a psychologist at the Menninger Clinic. ‘She’s a hero for choosing the conventional path.’

Film critic Robert Ebert would also offer in his review, that for him, the emotional peak of the film is “the renunciation, when Francesca does not open the door of her husband’s truck and run to Robert” (more on this later). This moment, says Ebert, and not when the characters first kiss or make love, “is the film’s passionate climax.”

People magazine at the time of the film’s release did a cover story on Meryl Streep featuring a screenshot from the film with her in the embrace of Clint Eastwood. “Meryl’s Passion,” was the headline for the magazine’s June 26th, 1995 edition, which added: “She has four kids and more than 40 years. But Meryl Streep is burning up The Bridges of Madison County – and hitting a nerve about lost love and midlife desire.”

Meanwhile, book sales in early Summer 1995 surged in response to the film, pushing the Waller book back up to No. 1 on the New York Times bestsellers list, June 25th, 1995. Bridges by then had been on that list for nearly three years. The book by late August 1995, still in hardback edition, had sold over six million copies in America and over ten million worldwide.

Also away from the farming community, Robert and Francesca visit a blues bar where jazz music played and they dance to a Johnny Hartman tune. |

At their final dinner together, Kincaid tries to persuade Francesca: “I’ll only say this once. I’ve never said it before. This kind of certainty only comes but once in a lifetime.” |

Unhappy Francesca facing the future without Robert Kincaid. |

After Francesca’s family returns, and during a trip to town with her husband on a rainy afternoon, she sees Kincaid in the middle of the street, drenched by the rain. |

Kincaid has remained in town solely on the chance that Francesca might reconsider. |

Her hand on the truck’s door handle, she considers bolting from her husband to join Kincaid, but cannot do it... This moment, for film critic Robert Ebert, “is the film’s passionate climax.” (more screen shots continue below in Sources). |

Farmhouse Jazz

Among some of Eastwood’s more interesting and subtle touches in the film are the scenes using and incorporating jazz music tracts. A jazz fan himself and pianist, Eastwood helped compose the film’s love theme, “Doe Eyes,” and he uses a number of jazz pieces throughout the film. Among these are songs by Johnny Hartman, Irene Kral, Dinah Washington, and Barbara Lewis. These music moments in the film have been noted by Janice Gomes in her essay, “Jazz in the Movies,” the source used, in part, for the summary that follows below.

In one of Eastwood’s earlier directing roles, Play Misty for Me, he built much of the film’s storyline around an Errol Garner love song of that same name. In Bridges, Eastwood’s use of the music is never dominant, but typically in the background.

The jazz tunes in Bridges are played on the kitchen radio in the Johnson farmhouse, heard on Kincaid’s pick-up truck radio, and played by a roadhouse band when Francesca and Robert visit an out-of-the-way dance bar.

Earlier, in the film, after Robert and Francesca have taken their first trip to the Roseman Bridge, and Kincaid has come inside her home for iced tea, he fiddles with the kitchen radio, finding Dinah Washington singing “Blue Gardenia,” befitting the blue wildflowers he picked for Francesca at the bridge, now on the kitchen table.

As they exchange stories in the kitchen, jazz and blues tunes continue to play on the radio. Among the songs is “When You’re in Love” by Johnny Hartman.

Francesca by this time has asked Robert to stay for dinner. As they both prepare the food for their meal, Dinah Washington is heard singing “I’ll Close My Eyes.”

After their dinner, “Easy Living” by Johnny Hartman is heard. Francesca that evening has left her note on the bridge inviting Robert to dinner the following day.

On Francesca’s drive into town the next day to buy groceries, Dinah Washington’s “Soft Winds” plays on her pickup truck radio. While in town, she decides to buy a new dress.

Later that night, at their second dinner, meeting in the kitchen, Robert is again tuning the radio, then turns to see Francesca in her new dress as the Johnny Hartman tune “I See Your Face Before Me” plays in the background.

A phone call briefly interrupts their evening, but they soon have their first moments of touching — she smoothing his collar while on the phone, leaving her hand resting on his shoulder.

As she ends the phone call, Robert takes her hand, leading to a slow dance around the kitchen as Johnny Hartman sings his tune. The love making is not far behind.

Later, as the two share a steamy bath, Irene Kral sings “This Is Always.” Also heard on the soundtrack is the Barbara Lewis hit from 1965, “Baby I’m Yours.”

Near the end of their four days together, they visit a roadhouse with jazz band and dance to Johnny Hartman’s “For All We Know,” as its lyrics, “we may never meet again,” presages their unhappy end.

Back at the farmstead on their final night together, Francesca has packed to leave with Robert. But as they share dinner, Johnny Hartman’s “It Was Almost Like A Song” plays in the background as Francesca realizes she cannot leave her family. “They would not survive the talk,” she says of the small-town censure and gossip mill.

After she and Kincaid have parted from their four-day affair, and when Francesca comes to town a few days later with her husband on errands, there is the scene in the pickup truck with her husband when she sees Robert standing in the middle of the the road in the rain. As the family pickup pulls away, Francesca has her hand poised by the door handle, but she does not bolt from the truck. She returns home and is shown in a later scene leaning against the kitchen wall sobbing as Irene Kral’s “It’s A Wonderful World” plays. Francesca will never see Robert Kincaid again.

Cottage Industry

On June 19, 1995 The New York Times ran a business-section story headlined, “The Revenue Streams That Flow From The Bridges of Madison County,” noting that “the book and the film version have generated a not-so-small cottage industry of their own.”

The Times story included a graphic which showed the book spawning the film version, and the film, in turn, spawning two related books, a music CD from the film (there were actually two CDs), and various ancillary products linked to the Bridges story – tote bags, polo shirts, a cookbook, picture frames with the Bridges imprint, and even a perfume.

Clint Eastwood’s recording label, Malpaso Records, a division of Warner Brother’s Records, released two CDs: the original soundtrack, Music from The Bridges of Madison County, and Remembering Madison County, a companion disc of more jazz tunes. Both rose to No. 1 on the Billboard jazz chart in June 1995, each with respectable sales that year as well.

Warner Books would publish the two-tie in book volumes from the film. The first, The Bridges of Madison County: The Film, a coffee table book of film-related photos. That book was priced at $22.95 and Warner, according to the Times, had 80,000 printed.

The second film-related book, The Bridges of Madison County Memory Book, meant to be a journal, had mostly blank pages but also included some text along with photos shot by Clint Eastwood as he was acting in his role as Robert Kincaid shooting the bridges and Francesca. That volume was priced at $11.95 with Warner printing 70,000 copies.

The original book itself was not published in paperback until 1997, and then with a print run of 1.5 million copies. And there would also be other Waller books to come (see below), several published by Warner (more on this below).

The film’s main CD soundtrack, mentioned earlier, the jazz soundtrack, which the Times said was priced at $15.05, had already sold 250,000 copies. That was mid-June 1995. A DVD version of the film was also released for sale not long after the film had its first run in 1995. A “deluxe edition” DVD of the film (first photo at the top of this story) was released by Warner Home Video in June 2008, and it included a number of extra features.

In 2014 a stage musical was made of Bridges which ran on Broadway at the Gerald Schoenfeld Theater for 137 performances. The production won several awards during its run in 2014. A national tour followed, which began in the Fall of 2015.

So, yes; cottage industry indeed. In fact, when all the Bridges-related business, entertainment, and economic activity is added up (from 1991 on) – including Iowa-based tourism, which became considerable over several years – it would not be surprising to find something north of $1-to-$2 billion in total economic activity generated by the Bridges phenomenon, and perhaps more.

More Waller

As for author Robert James Waller, he went on to write several other novels. In addition to Slow Waltz at Cedar Bend (1993) already mentioned above, he also published Border Music (1995), Puerto Vallarta Squeeze (1995), A Thousand Country Roads (2002), High Plains Tango (2005), and The Long Night of Winchell Dear (2006).

Of these, A Thousand Country Roads was published as “an epilogue” to Bridges, and it follows an older Robert Kincaid on a journey to Iowa in hopes of seeing Francesca again. However, the two do not reunite. Although this book did make the New York Times bestsellers list for a time, it was not another Bridges. Yet it did allow a few reviewers to revise earlier assessments of Waller and reflect more favorably on Bridges and why so many readers loved it.

In his personal life, meanwhile, Waller had become a multi-millionaire – estimated by one source to be in excess of $15 million with earnings from movie rights, publishers’ advances, and his share of U.S. book sales. Another report from Newsweek in June 1995 estimated Waller had made $26 million from The Bridges of Madison County.

In 1994, Waller moved to Texas and bought a ranch, and later, several thousand acres of land. His first marriage ended in 1997 amid an affair he was having with a younger ranch hand. He later remarried. In 2000, Waller named his graduate school alma mater, Indiana University, to an estate gift estimated to be “well into seven figures.” In 2012, Waller also made a multi-million dollar gift to the University of Northern Iowa, where some of his papers are also housed. Waller died on March 10, 2017, at his home in Fredericksburg, Texas. He was 77 and had been battling multiple myeloma.

One Story’s Legacy

When it was all said and done, The Bridges of Madison County, in its time, had one hell of a run. To date the book has reportedly sold 60 million copies worldwide and has been printed in some 23 languages. It spent 164 weeks on the New York Times bestsellers list, clearly helped by the film in its later run. In its prime-time occupation of that list during 1992-1995, Bridges out-performed and eclipsed other best-selling authors such as John Grisham, Danielle Steel, Stephen King, Tom Clancy, Anne Rice and others. The book holds one of the highest single-year sales records, with more than 4 million copies sold in 1993. In its day, it even surpassed Gone With the Wind as the best-selling hardcover fiction book of all time. It also garnered the 1993 American Booksellers “Book of the Year” Award as well as the 1993 Literary Lion Award from the New York Public Library. Yet in subsequent years, all of Bridges’ sales and publishing records would be broken by other best sellers.

Francesca on Roseman Bridge looking down on Robert Kincaid taking his photographs of the bridge shortly after they met. |

Robert Kincaid taking a few shots of his new friend. |

At Roseman Bridge, Robert had picked a bouquet of wildflowers for Francesca. |

Back at the farmstead, Francesca invites Robert in for iced tea. |

The Bridges film, meanwhile, was nominated for 15 awards overall, including the Golden Globe and Screen Actors Guild Awards, and won six. On one list, that for the French film magazine, Cahiers du cinéma, it was rated among the top three films of the 1990s. The film is also included on the American Film Institute’s “100 Years… 100 Passions” list of the 100 greatest love stories of all time.

While the book was pilloried for its sometimes flowery prose, lampooned for its macho descriptions, and called on the carpet for its depiction of women, Bridges still held its own with millions of readers. Among reviewers, there was also some grudging praise for Waller. Chauncey Mabe of The Sun Sentinel in Florida, for example, tipped his hat to the author. “Like Love Story before it,” wrote Mabe, “The Bridges of Madison County will survive the most scathing critical condemnation. Even those who like the book least… have to admit that it is skillfully put together.”

The Bridges of Madison County, however, is a two-part phenomenon, and its legacy should be that of book and film taken together as cultural package: the book for the central idea, and the film for the imagery of the idea, this alluded to, more or less, by several reviewers. The film, in toning down some of the literary excesses of the book, had the effect of redeeming and elevating the story. Waller provided the idea, the place, and circumstance; Streep and Eastwood, the characters and their love story visually embedded in memory.

Joan Ellis, writing in 1995 after the film had come out, noted: “…Robert James Waller’s style is irrelevant; what he did, it seems, is create a blank page for the collective fantasy. Bridges is an invitation to consider what might have been, permission to think about what was missed or what was lost. As Robert Kincaid and Francesca Johnson, Clint Eastwood and Meryl Streep become the vessels for the inner lives of their audience.”

Still, Bridges the book remains controversial to this day with its fans and foes, while others question its literary value. Some regard it as romance, others accept it as literature, and still others call it an adult fairy tale. Regardless of what it’s called, the story holds a fascination for people because of the important themes it explores: love, passion, chance, consequence, loyalty, and responsibility.

Periodically, it seems, popular love stories come along unpredictably — as they have through time. They appear to be welcomed in whatever form, and continue to capture the public’s imagination and support — whether Romeo or Juliet, its musical successor West Side Story, Casablanca, An Affair To Remember, Love Story, Dr. Zhivago, and countless others. The literary rank or comparative greatness of the stories does not always appear to enter the equation. If the story succeeds in moving its audience, causing them to think and feel along with the trials, challenges, and choices of the principal characters, that appears to be quite enough. The Bridges of Madison County — in print and on the big screen — surely did that.

See also at this website: “The Love Story Saga, 1970-1977,” on the book and film of that era that also became a publishing and box office hit; “Linda & Jerry, 1971-1983,” on the respective careers of and relationship between California Governor Jerry Brown and rock star Linda Ronstadt; and “Noteworthy Ladies,” a topics page with 40 story choices featuring famous women. See also the “Film & Hollywood” or “Print & Publishing” pages for additional stories in those categories. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing, and continued publication of this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

________________________________

Original Posting: 25 June 2008

Revision: August-September 2020

Last Update: 8 August 2022

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/PopHistoryDig

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Of Bridges & Lovers, 1992-1995,”

PopHistoryDig.com, June 25, 2008.

________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Robert James Waller, The Bridges of Madison County, Warner Books, New York, NY, 1st printing, April 1992, 171 pp.

“The Bridges of Madison County (book),” Wikipedia.org.

Carey Karpick, “Waller, James Robert: The Bridges of Madison County,” 20th-Century American Bestsellers, Depart-ment of English, University of Virginia, accessed August 2020.

“Robert James Waller,” Wikipedia.org.

“Robert James Waller Interview on The Bridges of Madison County,” The Charlie Rose Show, February 12, 1993, posted on YouTube.com, August 15, 2016.

“Books by Robert James Waller and Complete Book Reviews,” Author Page, PublishersWeekly.com.

Trisha Ping, Interview, “Robert James Waller: Home on the Range,” BookPage .com, July 2005.

Gilbert Cruz, “The Backstory Behind Best-Sellers,” Entertainment Weekly, December 27, 2006.

“Meryl Streep: Making of ‘The Bridges of Madison County’,” YouTube.com (with transcript), posted by The Meryl Streep Forum, June 4, 2010.

David Comfort, An Insider’s Guide to Publishing, 2013, Penguin, 304 pp.

Associated Press, “’Bridges of Madison County’ Author Robert James Waller Dies at 77,” Hollywood Reporter.com, March 10, 2017.

William Grimes, “Robert James Waller, Author of ‘The Bridges of Madison County,’ Dies at 77,” New York Times, March 10, 2017.

Matt Schudel, “Robert James Waller, Author of Best-Selling ‘Bridges of Madison County,’ Dies at 77,” Wash-ingtonPost.com, March 10, 2017.

Patricia Bauer, “Robert James Waller, American Author,” Britannica.com, Last Updated, July 28, 2020.

Noel Murray, “The Bridges Of Madison County” (film review), TheDissolve .com, May 5, 2014.

Hilary Radner, The New Woman’s Film: Femme-Centric Movies for Smart Chicks, 2017, Routledge, 224 pp. (Chapter 3: “Anticipating the Twenty-First Century: ‘Dirty Harry Bathed in a Romantic Glow?’ and The Bridges of Madison County”).

“The Bridges of Madison County” (film), Wikipedia.org.

“The Bridges of Madison County (1995),” AFI.com, American Film Institute.

“The Bridges of Madison County,” Film Trailer, IMDB.com (International Movie Data Base).

Ken Regan and Robert James Waller, Bridges of Madison County: The Film, 1995, Warner Books/Grand Central Pub-lishing, 128pp.

“The Bridges of Madison County,” Kirkus Reviews, January 15,1992.

“The Bridges of Madison County,” Pub-lishers Weekly, April 1992.

L. S. Klepp, “The Bridges of Madison County,” Entertainment Weekly, June 12, 1992.

“Best Sellers, August 16, 1992,” New York Times Book Review/NYTimes.com.

“Booksellers’ Art of Persuasion,” News-week, September 7, 1992.

Charles Champlin, “Sleepers,” Los Ange-les Times Book Review, January 17, 1993.

William Souder, “He Wrote the Book on Love” (re: Robert James Waller), Wash-ington Post, February 9, 1993.

Elaine Jarvik, “Love, Longing & `The Bridges of Madison County’,” Deseret News (Salt Lake city, UT), February 14, 1993.

Pauli Carnes, “Waller Book: Porn for Yuppie Women?,” Los Angeles Times Book Review, April 18, 1993.

“Oprah Winfrey Show (May 21, 1993),” YouTube.com (with transcript), posted, April 29, 2020.

Harpo Productions, “The Oprah Winfrey Show (May 21, 1993),” Archive.org, The Internet Archive.

Nancy Pate, Book Critic, “Waller’s ‘Bridges’ Is Still Connecting,” Orlando Sentinel (Orlando, FL), May 30, 1993.

Dan Thomas, Wartburg College and Larry R. Baas, Valparaiso University, “Reading the Romance, Building the Bestseller: A Q-Methodological Study of Reader Response to Robert James Waller’s The Bridges of Madison County,” Prepared for the Ninth Annual Meeting of the International Society for the Scientific Study of Subjectivity, Stephenson Research Center, School of Journalism, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri, October 7-9, 1993.

Charles Champlin, “Bridges of Madison County, Take Two: Slow Waltz in Cedar Bend,” Los Angeles Times, October 24, 1993.

Jocelyn McClurg, Book Editor, Connec-ticut News, “Waller, As The `Last Cowboy,’ Riding High in the Saddle,” Hartford Courant/Courant.com (Hart-ford, CT), November 12, 1993.

Jon Margolis, “What’s Pop Culture? Politics, Show Biz and Total Inanity,” Chicago Tribune, June 29, 1993.

“Rush Is on For Female Lead in ‘Madison County’,” The Courier-Journal (Louis-ville, KY), July 21, 1993.

Frank Rich, End Paper/Public Stages, “One-Week Stand,” The New York Times Magazine/NYTimes.com, July 25, 1993, Section 6, p. 54.

Sarah Lyall, Book Notes, “A Big Year for ‘Bridges’,” New York Times/NYTimes .com, July 28, 1993.

Lynn Van Matre, “The Marketing of Madison County,” Chicago Tribune, August 5, 1993.

Tim Warren, “Building Bridges; Senti-mental Novel Keeps Novice Writer on Top,” The Baltimore Sun, August 6, 1993.

Associated Press, “Bridges’ Carries Readers From Cover to Cover,” Port Arthur News (Port Arthur, TX), August 6, 1993.

Malcolm Jones, Jr., “Lists You Should Check Twice,” Newsweek, August 9, 1993.

John Leo, “‘Covered Bridges’: Written Proof of People’s Private Desperation,” U.S. News and World Report, August 9, 1993.

Chauncey Mabe, “’Bridges’ Album Starts Badly, Gets Worse,” Sun-Sentinel (So. Florida), September 8, 1993.

Malcolm Jones, Jr., “A Slow Waltz to the Bank.” Newsweek, November 1, 1993.

“Best Sellers, November 7, 1993,” New York Times Book Review/NYTimes.com.

Jane Applegate, “’Bridges’ Leads to Madison County Boomlet,” The Orlando Sentinel, November 29, 1993.

“Publishers Weekly List of Bestselling Novels in the United States in the 1990s,” Wikipedia.org.

“Slow Waltz in Cedar Bend,” Wikipedia .org.

First Draft, “The Bridges of Madison County,” Screenplay Adaption by Richard LaGravenese, March 24, 1994.

“Best Sellers, May 1, 1994,” New York Times Book Review/NYTimes.com.

Anne Thompson, “The Bridges of Madison County’s Tough Road; After Changes in Director’s and Leading Stars, The Best-Selling Novel Will Go to Film,” Entertainment Weekly, May 13, 1994.

Dana Kennedy, “Robert James Waller, A Real American Cowboy,” EW.com, De-cember 16, 1994.

“The Bridges of Madison County,” Vari-ety, May 22, 1995.

Jim Bessman, “Malpaso Debuts With ‘Bridges’ Soundtrack; Eastwood War-ner Label Specializes in Jazz” Billboard, May 27, 1995.

Mick LaSalle, “The Bridges of Madison County,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 1, 1995.

Amy Longsdorf, “Crossing the Bridge: The Long Road to the Filming Of’ Madison County’,” The Morning Call (Allentown, PA), June 2, 1995.

Janet Maslin, Review, “Love Comes Driving Up the Road, and in Middle Age, Too,” New York Times/NYTimes.com, June 2, 1995.

“The Bridges of Madison County,” USA Today, June 2, 1995.

Chauncey Mabe, Book Editor, “Script, Streep’s Acting Redeem ‘Bridges’,” Sun-Sentinel.com (South Florida), June 2, 1995.

Roger Ebert, Film Critic, “The Bridges Of Madison County,” Chicago Sun-Times /RobertEbert .com, June 2, 1995.

“Steven Schiff, Movie Critic, Reviews ‘Bridges of Madison County,’ Starring Clint Eastwood and Meryl Streep,” Fresh Air / NPR.org, June 2, 1995.

Desson Howe, “’Bridge’ Work Pays Off,” Washington Post, June 2, 1995.

R. Kempley, “’Bridges’: Iowa Corn,” Wa-shington Post, June 2, 1995.

“The Bridges of Madison County,” Warner Bros. Pictures | Release Date: June 2, 1995, Metacritic.com (Meta-score 66, i.e., “generally favorable reviews based on 22 critic reviews” ).

Barbara Shulgasser, Examiner Movie Critic, “The Weeper of Madison County,” San Francisco Examiner /SFGate.com, June 2, 1995.

Richard Corliss, “When Erotic Heat Turns Into Love Light,” Time, June 5, 1995.

Bernard Weinraub, “Rebuilding ‘Bridges’ Without Leaving The Novel Behind,” New York Times/NYTimes.com, June 6, 1995.

“Is ‘Madison County’ Novel Bridge to Hell?,” Louisville Courier-Journal (Lou-isville, KY), June 7, 1995.

“The Bridges of Madison County,” Enter-tainment Weekly, June 9, 1995.

Anne Thompson, “The Making of ‘The Bridges of Madison County’,” EW.com, June 16, 1995.

Jocelyn McClurg, Book Editor, “`Bridges’ Fans Far From Burnt Out,” Hartford Courant / Courant.com (Hartford, CT), June 21, 1995.

Thomas K. Lindsay, “New-Old Lessons on Love and Family,” The Baltimore Sun, July 12, 1995.

Jonathan Rosenbaum, “The Bridges of Madison County,” ChicagoReader .com, June 13, 1995.

“The Bridges of Madison County,” Roll-ing Stone, June 15, 1995.

Newsweek Staff, “A Place In The Heart,” Newsweek, June 18, 1995.

Ty Ahmad-Taylor, “The Revenue Streams That Flow From The Bridges of Madison County,” New York Times/NYTimes.com, June 19, 1995.

“Richard LaGravenese Interview on ‘The Bridges of Madison County’,” YouTube .com, posted, August 13, 2016 (excerpted from The Charlie Rose Show, June 20, 1995).

“Best Sellers, June 25, 1995,” New York Times Book Review/NYTimes.com.

Mark Harris, “‘The Bridges of Madison County’ Tie-Ins; Three Additional Books — A Diary, Postcards, and About the Film — Can Now Be Found in Stores,” Enter-tainment Weekly, July 21, 1995.

Cheryl Lavin, “A ‘Bridges of Madison County’ Reality Check,” Chicago Tribune, August 30, 1995.

“Best Sellers, October 8, 1995,” New York Times Book Review / NYTimes.com.

Ruth Picardie, “Making Megabucks From a Mid-Life Crisis,” The Independent (London), October 14, 1993.

Christine Tatum, “Romance Novel Hits Home With Local Fans `The Bridges of Madison County’,” News & Record (Greensboro, NC ), October 18, 1993.

Frank J. Prial, “Son of Madison County,” New York Times/NYTimes.com, October 31, 1993.

Joan Ellis, “That Bad Book Has Come a Long Way; The Bridges of Madison County,” Joan Ellis.com, 1995.

Bonnie Brennan, Marquette University, “Bridging the Backlash: A Cultural Materialist Reading of The Bridges of Madison County,” Studies in Popular Culture, October 1, 1996.

“The Bridges of Madison County,” in Tom Pendergast and Sara Pendergast (eds.), The St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, Gale Group, 2000.

Leslie Kaufman, “Novel’s Sequel: Bridges Are Burned; ‘Madison County’ Author Returns to His Best-Selling Characters,” New York Times/NYTimes.com, April 4, 2002.

Michael Pakenham, “Here Comes R. J. Waller Again, and Still Oblivious to Intimacy,” The Baltimore Sun, April 14, 2002.

Janis Gomes, “Jazz in the Movies,” TotalSwing.com, January 14, 2005.

“Robert J. Waller Papers, c. 1963-2002,” Special Collections & University Archives, University of Northern Iowa, UNI.edu, Cedar Falls, Iowa.

“Bridges of Madison County (Lennie Niehaus),” YouTube.com, Posted April 17, 2016.

“Bridges of Madison Magic (Lennie Niehaus – Main Theme; Irene Kral – This Is Always),” YouTube.com, posted by Madis Kaaret, January 17, 2017.

“The Bridges of Madison County – Awards,” IMDB.com.

Kyle Munson, “’Bridges of Madison County’ Made Robert James Waller Famous, But Didn’t Define Him,” Des MoinesRegister.com, March 13, 2017.

Philip Potempa, “Marriott’s ‘Bridges of Madison County’ Beautifully Brings the Page to Stage,” Post-Tribune/Marriott Theatre.com, July 3, 2017.

“An Old Fashioned Love Story: Making The Bridges of Madison County; Meryl Streep Clip,” YouTube.com, June 22, 2018.

“Streep in The 1990s: The Bridges of Madison County (1995),” SimplyStreep.com, May 2, 2020.

Aron Medeiros, “The Bridges Of Madison County – 25th Anniversary,” MauiWatch .com, June 4, 2020.

________________________________________