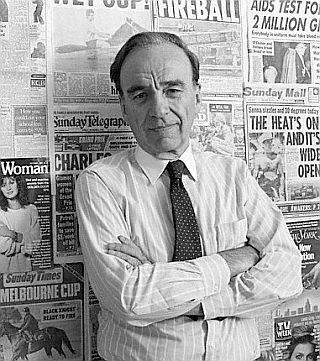

Jan 17, 1977: Rupert Murdoch depicted on Time magazine cover as the invading King Kong of New York publishing world, with Time’s editors offering a Murdoch-esque news banner. Click for copy.

By late January 1977, Murdoch would own two premier New York media companies: the New York Post newspaper and New York Magazine Co., which then published three magazines: New York, The Village Voice, and New West.

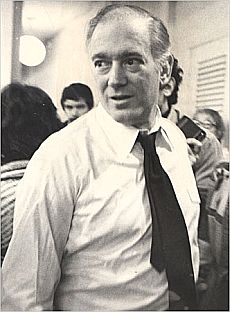

Rupert Murdoch in the 1970s was just getting started on his global media empire, and by today’s standards, his 1976-77 New York acquisitions seem tame. Yet these deals, and the changes Murdoch undertook with them at the time, shook things up in the media print world and hinted at his grander plans ahead.

In later years, Murdoch would create the Fox television network and acquire the Wall Street Journal, among other properties. His 1976-77 deals, though, were the first signs that Murdoch would be a determined player in the U.S. market.

These New York deals, however, were not the first Murdoch had made in America.

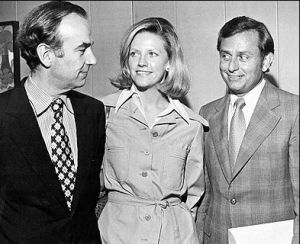

Murdoch and wife Anna in Texas, 1973.

By 1976, however, Murdoch had set his sights on the bigger eastern cities. He had looked at the possibility of acquiring some major women’s magazines, such as Redbook and Ladies’ Home Journal. But he was also considering starting a daily paper in either New York City or Boston, and that’s when the New York Post became available.

The New York Post had roots that dated to 1801, and one of its founders was Alexander Hamilton. For years it was known as the New York Evening Post, and described itself as the nation’s oldest, continuously-published daily newspaper.

The New York Post

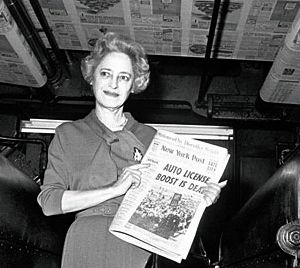

Dorothy Schiff, the publisher of The New York Post, with the presses running overhead in 1963.

When Murdoch remarked to Schiff at one meeting that he was thinking about launching a new paper in Boston or New York, Schiff, then 73, told him she was thinking of selling the Post. According to one account of the deal that followed, “Murdoch pounced, wrapping up the $30 million sale in three weeks of secret negotiations.” He acquired the paper by late November 1976.

Dec 20, 1971. |

Apr 22, 1974. |

Mar 17, 1975. |

Aug 23, 1976. |

New York Magazine Co.

After Murdoch made the Post deal, he moved next on the New York Magazine Co. This company was run by Clay Felker, an innovative editor and writer who had worked at various newspapers and magazines including Life, Sports Illustrated, Time, Esquire, and The New York Herald Tribune.

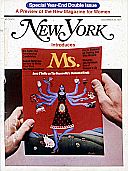

The flagship publication of the New York Magazine Co. was New York magazine, a weekly focused on culture, politics, and New York City style. New York magazine was begun in 1964 by Felker as a Sunday supplement enclosed with The New York Herald Tribune. After the Tribune folded in 1968, Felker and graphic designer Milton Glaser (who later invented the “I Love NY” logo) reintroduced New York as a glossy, stand-alone magazine.

New York initially was intended to compete with The New Yorker — and an earlier, scathing piece about the New Yorker’s “mumified” reporting in April 1965 when New York was still a Tribune supplement, had already set off a war between the two.

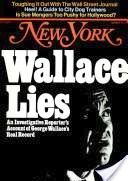

But New York magazine also became known for its own unique enterprise: helping launch and define what would be called the “new journalism” — a departure from the more objective norm of journalism to a form of narrative and point-of-view journalism relying on characters, dialogue, participant authors, and/or fictional devices.

Clay Felker in 1976 at ‘The Village Voice.’

“Felker had observed something new happening in the city, and he’d brought his own outsider’s sense of romance and a fascination with power and status. The magazine he made had a new palette of interests, with no brow distinctions. Restaurants were as important as business, or politics. Everything that went on in a city dweller’s mind was something to be curious about.”

The magazine, with Milt Glaser’s help, also did clever things with design, text, and illustration, also departing from the norm. New York magazine would become a model for many city and other magazines that would follow it in years to come.

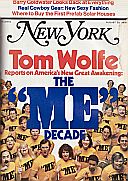

New York’s writers, editors, and contributors were some of the most talented to come out of the late 1960s and 1970s, including: Tom Wolfe, Jimmy Breslin, Nora Ephron, Kurt Andersen, Gloria Steinem, Gail Sheey, John Heilemann, Nick Cohn, Ken Auletta, Richard Reeves, Aaron Latham, Dick Schaap, Michael Kramer, John Simon, Pete Hamill, Gael Greene, Walter Bernard, Bill Flanagan, Anna Wintour, James Brady, Lally Weymouth, Andy Tobias, Judy Daniels, Laurie Jones, Nancy Newhouse, Nick Pileggi, Mark Jacobson, Robert Benton, Byron Dobell, Mimi Sheraton, Gael Greene, Dorothy Seiberling, Amanda Urban, Walter Bernard, and others.

But Clay Felker was the visionary leader and editorial maestro. As Tom Wolfe would put it, “he created the hottest magazine in America in the second half of the twentieth century: New York.”

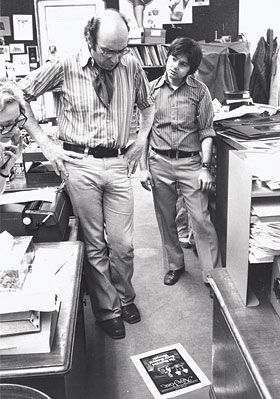

Milt Glaser & Walter Bernard at New York magazine offices pondering a cover design, 1974. (Photo: Cosmos Sarchiapone).

Tom Wolfe, wrote one of the magazine’s early features on 1960s’ psychedelic cultural renegade Ken Kesey and his band of pranksters, a story that later became the Wolfe novel, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

Gloria Steinem wrote about women’s issues for New York. She also wrote on the 1968 presidential election. Felker helped her launch her own publication in 1971, MS magazine, using New York to launch a sample insert issue (see cover above).

New York also covered New York sports stars, the arts, and national politics. In 1969, it did a story on Joe Namath, flamboyant quarterback of the New York Jets. In the 1970s, Richard Nixon and the Watergate scandal were covered closely.

In 1976, Nick Cohn wrote a New York story titled, “Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night,” an account of a young working-class Brooklyn guy who spent his evenings at a local disco club — a story that became a sensation and helped spawn the film Saturday Night Fever.

The New York Magazine Co. also owned two other publications — The Village Voice and New West. The Village Voice, originally established by writer Norman Mailer and others in October 1955, was merged with Felker’s company in 1974, continuing as The Village Voice. The newest member of the New York Magazine group by 1977 was New West, which Felker had launched in Los Angeles, California in 1976, modeled after New York. The circulation of each of the magazines at the time of Murdoch’s takeover in 1977 was as follows: New York, 375,000; the Village Voice, 162,000; and New West, 290,000. So, how did Rupert Murdoch come to own this company?

Murdoch vs. Felker

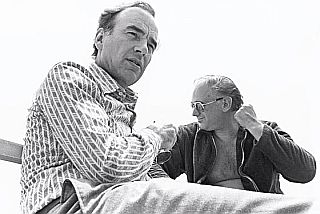

Rupert Murdoch & Clay Felker in East Hampton, NY in the 1970s, when the two newspapermen were “pals.”

Milton Glaser, Lally Weymouth, Clay Felker, and Katharine Graham in 1976. (Photo: Jill Krementz)

Murdoch saw another publishing asset to add to his New York base and began negotiating directly with the top shareholders at the New York Magazine Co. He wanted the whole company. Felker then sought allies in defense of Murdoch’s moves, eventually enlisting Katharine Graham of the Washington Post, who agreed to match Murdoch bid for bid — starting at $7 a share, then $7.50, then $8.25, matching his offers. But Murdoch by January 1, 1977 made a direct deal with Carter Burden, who then held the largest chunk of the company. Murdoch also lined up more than a dozen other shareholders in the New York Magazine Co. and soon held over 50 percent of the company. In the end, Murdock paid something on the order of $7.6 million for the New York Magazine Company.

Clay Felker addressing the troops at the Village Voice amidst Rupert Murdoch takeover in 1977. (Photo: James Hamilton).

“New West” magazine, had a look & tone much like “New York,” but it also helped to put the company in jeopardy.

“…He [Felker] always wanted to be respected as a businessman. Then he wanted to start New West. We didn’t have the money to do it. Clay was determined to do it. We reluctantly supported him. Clay spent freely, and he really wanted to create this footprint on both sides of the country. I remember going to Clay in ’76 saying, “Clay, we’re going to have to find some way of resolving this” — but he didn’t do much about it. Then Rupert Murdoch came along and was prepared to pay a premium on the price at the time. He knew that he was going to be buying something where Clay was not happy about it, and it wasn’t until the very last second, when the board had gone very far with Rupert, very far, at the midnight hour, that Clay produced Katharine Graham, but it was too late by then. He had plenty of time, but he didn’t want to face up to it. I have to tell you, it was one of the most reluctant sales I ever made…”

“…It was a time that we all thought the power was really with the writers, with the creative people, and in a way we learned what they learned in Hollywood: That’s not the way it is. The power is with the money…”

– Richard Reeves In the end, Murdoch won. Felker was not happy with the loss of his dream enterprise. At the first directors’ meeting following the deal, Murdoch demanded two seats on the New York Magazine Co. board — and got them. He also said to Felker at the time that he thought Felker was “an editorial genius” and wanted him to stay and run the magazine. Felker refused. In his departure from the company, Felker was paid $1.5 million for his shares plus his $120,000 salary for three years. The managing editors of New York, the Voice and New West, as well as the ten most senior New York writers, were all given two-year contracts by Murdoch. Clay Felker, meanwhile, went on to other magazines and editorial projects, briefly tried Hollywood, and later took a faculty position at the University of California at Berkeley. In 1995 he was honored with the creation of the Felker Magazine Center at Berkeley. After battling throat cancer for some years, he passed away in July 2008 at age 82 and was eulogized and fondly remembered by many of his former New York staff.

Richard Reeves, one of the early writers at New York, offered this observation on Felker, Murdoch, and the magazine changing hands in1977:

“…The story was Clay was a great editor and a bad businessman, and Murdoch sensed that. He was like a wolf or a shark. He could sense there was blood in the water, and he made his move. It was a time that we all thought the power was really with the writers, with the creative people, and in a way we learned what they learned in Hollywood: That’s not the way it is. The power is with the money. While we wrote about that all the time, and while Clay understood that intellectually, as a businessman I don’t think that he did.”

Measuring Murdoch

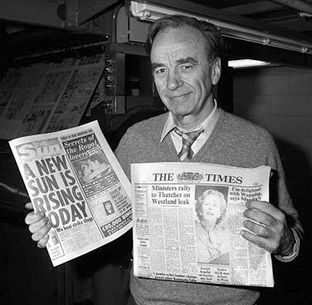

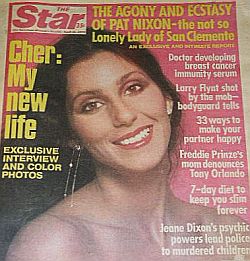

Now that Murdoch owned New York, The Village Voice, and the New York Post, the city’s publishing establishment began to size up their new neighbor and the kind of journalism he might be bringing their way. They looked at his record in Australia and the U.K, and what he had done in San Antonio and with his new national U.S. tabloid, The Star. What they found was not encouraging.

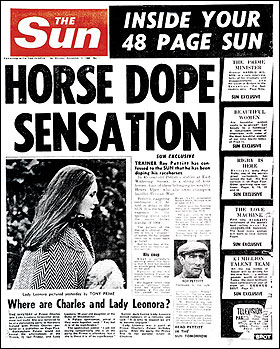

Rupert Murdoch shown with copies of his London newspapers “The Sun” and “The Times,” the latter of which he would acquire in 1981.

By 1968 Murdoch’s holdings included newspapers, magazines and broadcasting stations worth an estimated $50 million. He then turned to the U.K., making a bid in 1969 for the largest-selling British Sunday newspaper, The News of the World. With $20 million he outbid British book publisher Robert Maxwell and won controlling interest of the “Sunday scandal sheet,” as some called it. News of the World then had a circulation of about 6 million. A year later, also in London, he acquired The Sun, a daily broadsheet newspaper associated with Labor politics; a paper then in poor condition with a circulation of about 950,000. The Sun had begun in 1964 with noble aspirations, designed to tap into the lifestyle changes of the 1960s and the rise of the young, upwardly-mobile professionals, including career-oriented women. Murdock and his editors turned it into a tabloid, shifted the emphasis away from Labor politics, and moved to more titillating topics using a formula of “sex, sport and sensation.”

First edition of The Sun (U.K.) under Rupert Murdoch, Monday, Nov 17, 1969.

“Page Three Girls”

In November 1970 — about a year after The Sun’s first edition — a nude photo of German model Stephanie Rahn appeared on page three of The Sun. It was the first nude photo, shot from the side with breast area exposed, that a major circulation U.K. newspaper had run. Murdoch, out of the country when the photo ran, was reportedly upset over the move at first, but after the circulation numbers rose, accepted it. Page Three girls boosted circulation — from about 1 million in 1969 to 3.8 million in 1977 by one count — and made The Sun one of the most popular newspapers in the U.K.Thereafter, “the Page Three girl” became a regular feature. A year earlier, Murdoch’s first edition of The Sun had included a “glamour page” using clothed models, some with unbuttoned shirts or in otherwise provocative poses, but none that were nude or topless. With the Stephanie Rahn photo of November 1970, however, a new era had begun, as the Page Three girls were gradually shown in more overtly topless and/or suggestive poses. Over the next four years The Sun published photos of topless Page Three girls intermittently, going daily with the feature in 1975. Although controversy ensued, the Page Three girls boosted circulation — from about 1 million in 1969 to 3.8 million in 1977 by one count — and made The Sun one of the most popular newspapers in the U.K. Competing U.K. tabloids the Daily Mirror and Daily Star, instituted similar features in their papers. Today, “Page Three” and “Page 3” are registered trademarks of News International Ltd, the parent company of The Sun. In 1999, The Sun also launched a Page Three website, Page3.com, complete with online archive.

The Sun newspaper in the 1970s also ran feature stories with headlines such as, “Do Men Still Want To Marry A Virgin?” and “The Way into a Woman’s Bed.” The Sun would also run serializations of best-selling erotic books. Portions of The Sensuous Woman by “J” (Joan Garrity), first published in 1969, were run in Murdoch’s Sun at a time when copies of the book were being seized by British customs, causing a stir in London, but providing some free publicity for Murdoch’s newspaper.The Sun also ran excerpts from Jacqueline Suzann’s 1969 novel, The Love Machine. Through the 1970s, The Sun would overtake the Daily Mirror to become the UK’s biggest selling daily. Back in Australia, meanwhile, Murdoch in 1972 acquired another Sydney newspaper, The Daily Telegraph, a morning tabloid. But he also began looking elsewhere around the world.

Murdoch in Texas

By 1973, Murdoch had turned his attention to America, buying up his first two newspapers in San Antonio, Texas — the San Antonio Express and San Antonio Evening News from the Harte-Hanks news group. Reportedly, Murdoch flew into town and made the deal in a single day, signing the papers at the airport, but leaving instructions on his way out to turn one of the papers “into a screamer.”

Rupert Murdoch with wife Anna and Robert G. Marbut, of Harte-Hanks Newspapers in San Antonio, 1973 (photo: San Antonio Express-News).

An example of San Antonio News “rack-card” advertising, 1970s.

“…Readers of the News are learning things that five years ago they never dreamed they might be privileged to know: ‘Nude Principal Dead in Motel,’ for example, or ‘Armies of Insects Marching on S.A.’. The front pages regularly impart disconcerting information: ‘Handless Body Found.’ Or, ‘Screaming Mom Slain.’ Or, ‘Uncle Tortures Tots with Hot Fork.’ …The columns of the paper are populated by an unforgettable (and recyclable) cast of characters: tots, oldsters, thugs, nudies, grannies, moms.”

Time magazine, in one January 1977 review of Murdoch’s San Antonio paper, observed that “the front page of the News is virtually devoid of substantial news.” Only “the diligent reader,” concluded Time, would discover any meaningful reporting on politics or national policy issues.

The Star

An April 1978 edition of “The Star” then featuring Cher and assorted other stories.

But in 1977, what Murdoch’s New York city neighbors in the publishing biz wanted to know was: would his tabloid publishing style from the U.K., San Antonio, and The Star now carry over into the New York Post, New York magazine, and the Village Voice?

Murdoch in New York

Some of the fears about what Rupert Murdoch would do with his New York acquisitions were realized, but some weren’t. The New York Post turned for the worst, according to some, but New York and The Village Voice, by most accounts, did not seem to change substantially.

April 23, 1979. |

March 16, 1981. |

Jan 31, 1983. |

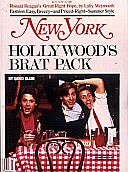

June 1985. |

At New York, Murdoch initially had a succession of editors in the 1970s, followed by Edward Kosner, of Newsweek, who Murdoch hired in 1980. Murdoch also acquired another magazine, Cue, a listings magazine that had covered the city for more than 50 years. Murdoch folded Cue into New York, which added value to New York with a going-out guide, while eliminating a competitor. New York’s content, meanwhile, tended toward a mix of news- magazine-style, trendy pieces, articles on shopping and consumer topics, and close coverage of the glitzy 1980s New York scene epitomized by financiers Donald Trump and Saul Steinberg. Other stories focused on national and New York political figures or the major issues of the day. The magazine was profitable for most of the 1980s and its stories sometimes permeated popular culture, as in mid-1985 when the term “Brat Pack”was coined by New York — used in a cover story to describe a group of young Hollywood film stars that variously included: Emilio Estevez, Anthony Michael Hall, Rob Lowe, Andrew McCarthy, Demi Moore, Judd Nelson, Molly Ringwald, Ally Sheedy, Tom Cruise, C. Thomas Howell, Matt Dillon, Ralph Macchio, Charlie Sheen, and James Spader. Meanwhile, given New York’s survival and good standing through the 1980s, the earlier worries of Murdoch trashing the magazine seemed over done. Even his critics would later concede that he did not fundamentally change New York magazine.

Village Voice, March 1981.

Over at The Village Voice, meanwhile, many employees there also feared for the paper’s quality under Murdoch, at least initially. And Murdoch did make a number of personnel changes at the Voice, but largely allowed the paper run itself. Some found in subsequent years that the Voice had actually become closer to its original form, hitting a steady circulation of about150,000, where it remained for several years. In 1981, The Voice received a Pulitzer Prize for the feature writing of Teresa Carpenter.

The biggest changes that Murdoch brought to his acquired New York publications, however, were those that came at the New York Post.

Murdoch’s Post

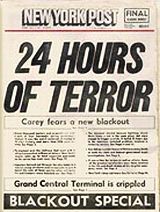

New York Post's "blackout special" edition, July 14, 1977.

First, it was the summer of the great New York city blackout of July 13-14, 1977 that created near panic in the city for about two days, during which the city suffered heavy looting and civil unrest. Over 3,000 people were arrested. “They [The New York Post] handled the blackout stories by exaggeration and by scare headlines over their stories and on their front pages,” recalled Thomas Kiernan on a PBS Frontline TV documentary. “The impression was created that there was an impending threat of a kind of race war in New York.” The Post published a “Blackout Special” on the first day following the blackout with the giant front-page headline: “24 Hours of Terror,” also noting in smaller headlines that New York Governor Carey “fears a new blackout” and that Grand Central Station was “crippled.” Inside the paper was a special pullout section headlined, “A City Ravaged.” New York City’s deputy mayor, Osborn Elliott, sent a letter to Murdoch during the crisis suggesting his paper had made the situation worse. Mayor Abe Beame was more direct, calling Murdoch an “Australian carpetbagger” who “came here to line his pockets by peddling fiction in the guise of news.” Across town, at the rival Daily News, Pete Hamill wrote: “Something vaguely sickening is happening to that newspaper, and it is spreading through the city’s psychic life like a stain.”

NY Post “Son-of-Sam” story, August 10, 1977.

August 18, 1977 NY Post Elvis Presley story & drug revelations from Steve Dunleavy book.

In addition to the 1977 front-page stories covering Elvis, the blackout, and Son-of-Sam, Murdoch also put his Post squarely in the middle of the New York city politics — and particularly so in the promotion of Ed Koch for mayor. Koch, then a U.S. Congressman, later recalled in a PBS Frontline documentary, a phone call he received one day in 1977 from Murdoch:

…When the phone rang, the voice on the other end said something like, “Congressman Koch, please.” I said, “Speaking.” He said, “Congressman, this is Rupert,” and I guess I was still a little sleepy maybe. I said to myself, “Rupert? Rupert? Rupert’s not a Jewish name. Who could be calling me at 7:00 o’clock in the morning named Rupert?” And then suddenly, because he was speaking, I realized it was Rupert, the Australian. I mean, the voice came through. And I said, “Yes, Rupert?” He said, “Congressman, we’re going to endorse you today on the front page of the New York Post and I hope it helps.” I said, “Rupert, you’ve elected me.”

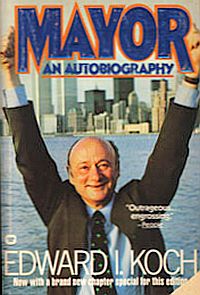

Ed Koch: Former U.S. Congressman who Rupert Murdoch’s NY Post helped elect mayor in 1977. Click for book.

In 1977, Koch ran in the Democratic primary against incumbent mayor Abe Beame. Also in the primary were candidates Bella Abzug, Mario Cuomo, and others. Koch ran to the right of the other candidates, on a “law and order” platform, using the blackout and crime as major issues, promising to restore public safety. Still, Rupert Murdoch’s decision to have the Post endorse Koch in both the primary and the general election was key.

According to one poll, only 4% of voters even knew who Koch was before Murdoch’s Post endorsed him. Koch proceeded to win the initial vote in the Democratic primary as well as a runoff between he and Cuomo. In the general election, too, Koch prevailed, not only crushing Roy M. Goodman, the Republican candidate, but also beating Cuomo for a third time, as Cuomo ran on the Liberal Party ticket. Journalist Jonathan Mahler, who would write the 2005 book The Bronx is Burning, later observed: “Murdoch had wagered that Koch represented his best shot at becoming a kingmaker in his new town.”

Murdoch’s Post, meanwhile, would continue to collect criticism for its political coverage, both during the 1977 mayoral race as well as subsequent gubernatorial and presidential elections. During the month before the 1977 mayoral primary, the Post’s early editions ran nothing unfavorable about Ed Koch, but there were unflattering stories about Koch’s opponents, including Mario Cuomo. One of the latter used the headline, “The Blond Millionairess Whose Big Bucks Back Cuomo.” Koch also received more favorable front-page headlines and more front-page ink in the Post than all of the other candidates, including the incumbent, Mayor Abraham Beame, who had already lashed out at Murdoch, calling him an “Australian carpetbagger.”Ken Auletta, later writing for the New Yorker, would also observe: “When Murdoch endorsed Edward I. Koch for mayor…, his support spilled over onto the news pages of the Post, with the paper regularly publishing glowing stories about Koch and sometimes savage accounts of his four primary opponents.” But after the election, adds Auletta, “fifty of the sixty reporters on the paper signed a petition of protest to Murdoch.” Murdoch reportedly invited them to quit, and twelve did.

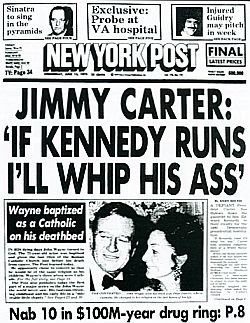

The New York Post was one of a few newspapers to run Jimmy Carter’s June 1979 quote about Ted Kennedy on its front page.

Later in the 1980 presidential race between Carter and Ronald Reagan, Murdoch’s Post supported Reagan. And some of the Post‘s news columns during the campaign used headlines that tilted to Reagan such as: “Reagan: I’ll Save the Middle Class” — a headline which ran in red ink on the front page. Other Post stories featured celebrities for Reagan but not Carter, with headlines such as, “Stars Want Ron to Get the Part.” The Post also ran a headline the day before the Reagan-Carter election that said, “Kohmeni Pulls Strings,”a slam on Carter’s then difficult going with a hostage situation, then a hot-button election issue.

Rupert Murdoch in the New York Post press room with a copy of a Ronald-Reagan era edition of the paper, 1980s.

In any case, within five years of making his New York acquisitions, Rupert Murdoch had become something of a political broker and kingmaker, both locally and nationally, by virtue of his media holdings. And there was much more to come. “Murdoch says he loves newspapers because they give him the power to help shape the public mind and, as always, he loves to win,” observed Ken Auletta in the 1995 Frontline documentary. Robert Spitzler, who had been managing editor at the New York Post, added in that same documentary:

“Rupert is a power junkie, in the sense that he enjoys the company of people with power. He also holds them in a certain degree of contempt…

When Rupert first came to New York, he was an Australian of no particular reputation. He bought the New York Post, suddenly he becomes an intimate, so to speak, with mayors, with governors and the president. You can’t ignore a guy who runs a New York newspaper….”

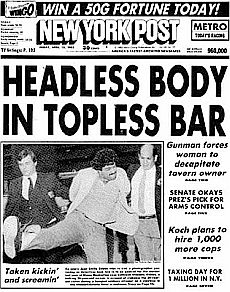

Meanwhile, out on the newsstands, Murdoch’s New York Post continued to shock with the best of them, using sensational and gritty headlines to sell its papers. One of the all-time classics in the outrageous headline department is the New York Post’s April 1983 classic, “Headless Body in Topless Bar,” shown at left, which described a robbery at a Brooklyn strip club in which the gunman herded all the customers into one room, shooting and decapitating the tavern owner.Other front page headlines at the Post could play to the popular hero of the moment, such as New York city subway rider Bernie Goetz who turned to vigilantism in December 1984 when he shot four would-be muggers on the New York subway. The incident made headlines for months at the Post and elsewhere. In 1985, when Goetz turned himself in, the Post ran the front-page headline, “I Am Death Wish Vigilante.” Other classic front-page headlines in the Post during the first Murdoch era ran the gamut of stories — crime, politics, sex, sports and scandal. The Post in recent years apparently became quite happy with the notice its front-page headlines received, as it compiled a collection of them in a 2008 book using the title, Headless Body in Topless Bar: The Best Headlines from America’s Favorite Newspaper.

Change & Sell Off

Rupert Murdoch’s media reach in the 1980s and 1990s was extending more into broadcast and satellite television, although print and publishing would remain important to Murdoch. Still, his 1976-77 New York publishing acquisitions — the New York Post, New York magazine, The Village Voice — as well as his San Antonio newspapers and supermarket tabloid, The Star, were all sold off during the late 1980s and early 1990s for various reasons. Among these sell-offs, however, the New York Post would be re-acquired by Murdoch later. More on that in a moment.

Rupert Murdoch, against a wall of his various publications at his New York Post office, 1985.

In 1985 he put the Village Voice up for sale when the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) blocked his purchase of a New York radio station unless he sold off one of his New York papers. So at that point, he sold the Voice to Leonard Stern, heir to the Hartz Mountain pet food company, for $55 million. But Murdoch was also confronting cross-ownership media rules in other parts of his burgeoning U.S. empire — and in the process, coming up against some unfriendly politicians. Among the latter was U.S. Senator Ted Kennedy, who Murdoch’s papers and TV stations had covered in some unflattering ways, including dredging up and re-broadcasting some old news about Kennedy’s 1969 Chappaquiddick, Massachusetts automobile accident, in which a Senate aide named Mary Jo Kopechne had been killed.

Murdoch, however, had enjoyed a “temporary” waiver under FCC rules enabling him to own both a newspaper and a broadcast station in the same city. Murdoch profited from that waiver in New York, Boston, and other markets where he owned newspapers and broadcast stations. However, by the late 1980s,One headline in the Herald read: “Kennedy’s Vendetta,” calling the Sen- ator “fat boy” in a front- page editorial. Ted Kennedy and Senator Fritz Hollings backed a rider to a budget bill that ordered the FCC to strictly enforce the media ownership rules, eliminating waivers such as that held by Murdoch. So Murdoch went to war. He turned his Boston Herald and New York Post headline writers loose on Kennedy. One headline in the Herald read: “Kennedy’s Vendetta” and included some prose in a front-page editorial calling Kennedy “fat boy.” The New York Post ran one headline during the controversy that announced, “It’s War on Post Busters.” In addition, Murdoch went on CNN’s “Crossfire” TV show to publicly plead his case. “We’re keeping the Boston Herald in spite of Senator Kennedy,” he said. Murdoch explained he would sell his small Boston TV station if necessary, but keep the newspaper. However, in the end, Murdoch was forced to sell off the Boston Herald. In New York, he would also sell off the New York Post for $37.6 million, as he could not give up his New York TV station since it was the flagship for his new Fox television network. But Murdoch wasn’t finished with the New York Post in 1988; he would return. In the meantime, however, he went shopping elsewhere, acquiring TV Guide and others at Triangle Publications for $3 billion.

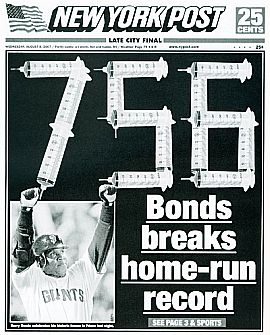

After Rupert Murdoch re-acquired the New York Post in 1993, creative headlines continued to appear, as in the Barry Bonds “hypodermic needle” home run record story.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, Murdoch was buying and selling media properties as the situation and his expansion plans required. In 1993, the New York Post came on the block again, as it was in poor shape financially and nearly bankrupt. But in order for Murdoch’s News Corp. to acquire the Post, a waiver from the same FCC rules that required him to shed the paper five years earlier was required. This time, a number of politicians, including Democratic New York governor Mario Cuomo, came to Murdoch’s support and persuaded the FCC to grant him a permanent waiver from the cross-ownership rules. Without that ruling, the New York Post would have shut down, but instead, under Murdoch’s renewed direction, the Post more or less picked up where it left off when Murdoch first owned it. In recent years, criticism of the paper’s style and sensationalism has appeared in selected articles and at various websites, including one list of documented 1997-2009 items at Wikipedia.org.

Rupert Murdoch on the July 2006 cover of Wired magazine: “Rupert Murdoch, Teen Idol! – News Corp & The Future of My Space”(later sold for big loss; “huge mistake,” Murdoch would later say).

Rupert Murdoch, meanwhile, continued to build his media empire through the 2000s, acquiring most notably in recent years, MySpace.com in 2005 for $580 million, and the Wall Street Journal in July 2007 for $5 billion. The MySpace deal, however, proved to be a bad bet for Murdoch, and by June 2011 that company was sold for a gigantic loss, fetching only a reported $35 million sales price. Some compared it to another bad deal of the new internet age – the Time-Warner purchase of AOL, covered in the Ted Turner story at this website.

For additional stories at this website on newspaper and magazine history, see for example:

“Empire Newhouse, 1920s-2012” (the rise of Sam Newhouse and family as newspaper/ magazine/ publishing powers and “culture makers,” with magazines such as Vanity Fair and The New Yorker, among others);

“Newsweek Sold!, 1961″ (history of the Washington Post’s acquisition of Newsweek, Ben Bradlee/Phil Graham role, and more recent history through Newsweek’s demise and the Jeff Bezos acquisition of the Washington Post);

“FDR & Vanity Fair, 1930s” (politics & publishing during the New Deal era);

“Ted Turner & CNN, 1980s-1990s” (rise of Turner’s all-news cable TV channel, CNN, and his impact on the media industry); and

“Rockwell & Race, 1963-1968,” (Norman Rockwell’s art on this topic at The Saturday Evening Post and Look magazine).

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________

Date Posted: 25 September 2010

Last Update: 25 July 2021

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Murdoch’s NY Deals, 1976-1977,”

PopHistoryDig.com, September 25, 2010.

____________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“The Battle of New York,” Time, Monday, January 17, 1977.

David Gelman, “Press Lord Captures Gotham,” Newsweek, January 17, 1977.

“The Press: Krusty Kay Tightens Her Grip,” Time, Monday, February 7, 1977.

“The Press: California’s Magazine War” (re: New West magazine), Time, Monday, August 29, 1977.

David Gunzerath, “Rupert K. Murdoch, U.S./ Australian Media Executive,” The Museum of Broadcast Communications.

“New York Post,” Wikipedia.org.

Bill Abrams, “Murdoch Will Sell the Village Voice to Stern of Hartz – Controversial Chief of Firm That Produces Pet Food to Pay $55 Million,” Wall Street Journal, June 21, 1985.

Jennifer Senior, “Tabloid Queen” (Book Review of, The Lady Upstairs: Dorothy Schiff and The New York Post, by Marilyn Nissenson, St. Martin’s Press), New York Times, April 22, 2007

James Brady, “On Media: Feats Of Clay,” Forbes, October 5, 2006.

Kurt Andersen, ‘Clay Felker, 1925-2008,” New York, July 1, 2008.

Joe Garofoli, “Media Maestro Clay Felker Dies At 82,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 2, 2008.

Tom Wolfe, “A City Built of Clay,” New York, July 6, 2008

Sarah Bernard & Aaron Latham, “My God, What Trouble You Could Cause!” (re: Clay Felker), New York, July 6, 2008.

“A Look Back at Memorable Covers From Felker’s Career,” New York, July 6, 2008.

Robert J. Bliwise, “The Master of New York: Clay Felker,” Duke Magazine, Duke Universtiy, date

Robert Struckman, “Clay Felker, Master of the Magazine,” NewWest.net, July 1, 2008.

Stacy Perman, “The Heart [symbol] and Mind of Milton Glaser,” Business Week, January 4, 2006, and Slide Show.

Michael Wolff, “’35 Years’ The Story of New York,” New York, March 31, 2003.

Editors, New York Magazine, Highbrow, Lowbrow, Brilliant, Despicable: Fifty Years of New York Magazine, 2017 edition, Simon & Schuster; illustrated, 432 pp. Click for copy.

“Who’s Afraid of Rupert Murdoch?,” Frontline, PBS, WGBH Educational Foundation, 1995.

“Village Voice Media, Inc.,” International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 38. St. James Press, 2001.

James Fallows, “The Age of Murdoch,” Atlantic Monthly, September 2003, pp. 81-98.

Robert Kolarik, “San Antonio Express-News History, Part 3: Wild In The Streets,” San Antonio Express-News, July 10, 2008.

“The Sun (United Kingdom),” Wikipedia.org.

“Page Three,” Wikipedia.org (for more on topless photos used by The Sun)

Deirdre Carmody, “Clay Felker, Magazine Pioneer, Dies at 82,” New York Times, July 1, 2008.

“Founding Father of New Journalism,” Duke University, 2008.

Deirdre Carmody, (1995-04-09). “Conversations / Clay Felker; He Created Magazines by Marrying New Journalism to Consumerism,” New York Times, April 9, 1995.

“Clay Felker,”Duke University (use Search option there).

Dennis Mclellan, “Clay Felker, 82; Editor of New York Magazine Led New Journalism Charge,” Los Angeles Times, July 2, 2008.

Marc Weingarten, The Gang That Wouldn’t Write Straight, 2006.

Laurence Zuckerman, Ted Gup, and Lawrence Malkin, “Fat Boy vs. the Dirty Digger,” Time, Monday, January 18, 1988.

John Cassidy, “Murdoch’s Game,” The New Yorker, October 16, 2006.

Ken Auletta, “Promises, Promises,” The New Yorker, July 2, 2007.

Martin Phillips, “We Are 40 Tomorrow,” The Sun, November 16, 2009.

Mary Braid, “Page Three Girls – The Naked Truth,” BBC News Online, Tuesday, September 14, 2004.

Torin Douglas, “Forty Years of The Sun,” BBC News Online, Tuesday, September 14, 2004.

David Blum, “Hollywood’s Brat Pack,” New York, June 10, 1985, pp. 40-47.

Jonathan Mahler, Ladies and Gentlemen, The Bronx Is Burning: 1977, Baseball, Politics, and the Battle for the Soul of a City, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, March 2005, 368 pp.

Mitchell Stephens, “His News Is Bad News,” Newsday, April 2, 1993.

“A Fun Bookstore Find: Collected NY Post headlines,” VisualEditors.com, Tuesday, January 19, 2010.

Jonathan Mahler, “What Rupert Wrought,” New York, May 21, 2005

“50 Years/50 Covers,” VillageVoice.com.

“Press: Whip His What?,” Time, Monday, Jun. 25, 1979

Steve Stecklow, Aaron O. Patrick, Martin Peers & Andrew Higgins, “Calling the Shots: In Murdoch’s Career, a Hand on The News; His Aggressive Style Can Blur Boundaries; ‘Buck Stops With Me’,” Wall Street Journal, June 5, 2007.

Allan R. Gold, “Kennedy and Paper Battle in Boston,” New York Times, January 7, 1988.

Allan R. Gold, “Kennedy vs. Murdoch: Test of Motives,” New York Times, January 11, 1988.

New York Post Staff, Headless Body in Topless Bar: The Best Headlines from America’s Favorite Newspaper, March 25, 2008, 208 pp.

Steven Cuozzo, It’s Alive! How America’s Oldest Newspaper Cheated Death and Why it Matters, New York: Times Books, 1996, 342 pp. Click for copy.

Paul Farhi, “Murdoch, All Business: The Media Mogul Keeps Making Bets Amid Strains in His Global Empire.” Washington Post, February 12, 1995.

David M. Alpern, “What Makes Rupert Run?” Newsweek, March 12, 1984.

Thomas Kiernan, Citizen Murdoch: The Unexpurgated Story of Rupert Murdoch–The World’s Most Powerful and Controversial Media Lord, 1986, Dodd Mead, 337 pp. Click for copy.

Thomas Moore and Marta F. Dorion, “Citizen Murdoch Presses for More.” Fortune, July 6, 1987.

William H. Meyers, “Murdoch’s Global Power Play,” New York Times, June 12, 1988.

Roger Cohen, “Rupert Murdoch’s Biggest Gamble.” New York Times, October 21, 1990.

Richard Brooks, “Murdoch: A Press Baron Re-Born.” Toronto Star, September 12, 1993.

Elizabeth Jensen and Daniel Pearl, “One Dogged Lawyer Shakes Murdoch Empire.” Wall Street Journal, April 6, 1995.

Nick Davies, Hack Attack: The Inside Story of How the Truth Caught Up with Rupert Murdoch, 2014, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 448 pp. Click for copy.

Christopher Williams, The Battle for Sky: The Murdochs, Disney, Comcast and the Future of Entertainment, 2019, Bloomsbury Business, 272 pp. Click for copy.

____________________________