June 1938 cover of Fortune magazine featuring a rendering titled “Highways” by illustrator, Hans Barschel. Click for magazine.

Indeed, for a car manufacturer, a nation of highways was certainly the preferred vision of the future. And, as it turns out, 100 years later, Durant wasn’t far off the mark.

However, what follows here is not a celebration of 100 years of highway building – although, to be sure, highways in America have contributed mightily to economic growth. Rather, after a bit of highway history, this story will focus on the citizen rebellion to highways that occurred throughout mid-20th century America – when major highways were pushed into developed urban and metropolitan areas without much care for resident displacement, social costs, and/or environmental impact.

But yes, in America today, highways are indeed everywhere. However, it didn’t start out that way. In fact, for many decades America was a nation of muddy, rutted and ill-maintained dirt, gravel, cobblestone roads.

The first crossing of the continent by car in 1903 required 44 days of sometimes perilous driving. By train, however, it took just 4 days. A “highway census” performed by the federal government in 1904 found just 141 miles of paved roads outside cities. By the time Henry Ford began mass-producing his Model-T automobiles in 1913, much of America, even as industrialization was underway, was still rural and agricultural with dirt roads across most of the country.

In July thru September 1919, a 28 year-old U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel named Dwight D. Eisenhower – later the U.S. President who would champion the 1950s Interstate Highway Act – was part of U.S. Army Motor Transport Corps convoy seeking to report on the nation’s road system. Their months-long journey took them 3,200 miles across country, from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco, discovering, for example, that practically all roadways of that day from Illinois through Nevada were unpaved, many with wooden bridges of dubious integrity, especially in the west.

Any nation with hopes of economic growth would need good roads, certainly. And it wasn’t long before various booster, civic, business groups, and government agencies arose to take up that cause, later evolving into a major power center in America’s economy and it politics. More on that later.

Entrance to GM’s Futurama pavilion at the 1939 Worlds Fair where thousands lined up daily to view the “1960 City of Tomorrow” exhibit with its superhighways & high-rise modernity. |

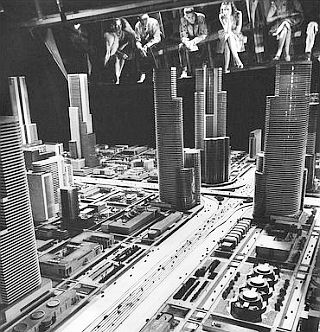

Inside, revolving theater seats circled above a fantastic layout of the modern city titled, “Highways and Horizons.” |

1939. View of seated patrons (at top) peering into GM’s “Highways & Horizons” layout in the Futurama theater. |

Meanwhile, early visions of super-highways came from architects and city beautiful dreamers such as French architect Le Corbusier, a leader of the modernist design movement who drew grade-separated urban highways amid high-rise buildings in his “City of Tomorrow” plan for Paris in 1925.

Then there was the General Motors “Futurama” pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York which included various futurist exhibits, one of which was “Highways and Horizons” a theater-like experience with seating that revolved around a detailed city scape model below. It was described as follows:

Futurama is a large-scale model representing almost every type of terrain in America and illustrating how a motorway system may be laid down over the entire country—across mountains, over rivers and lakes, through cities and past towns—never deviating from a direct course and always adhering to the four basic principles of highway design: safety, comfort, speed, and economy.

The GM exhibit was designed by Norman Bel Geddes, who had built an earlier, smaller “city of tomorrow” model for a Shell Oil advertising campaign in 1937. But the GM undertaking was much grander and became a hit at the Worlds Fair, as Geddes would later recount:

“Five million people saw the Futurama of the General Motors Highways and Horizons Exhibit … during the summer of 1939. In long queues that often stretched more than a mile, from 5,000 to 15,000 men, women and children at a time, stood, all day long every day, waiting more than an hour for their turn to get a sixteen-minute glimpse at the motorways of the world of tomorrow.”

Geddes explained the reason visitors came to the exhibit was that many were frustrated motorists “harassed by the daily task of getting from one place to another, by the nuisances of intersectional jams, narrow, congested bottlenecks, dangerous night driving, annoying police-men’s whistles, honking horns, blinking traffic lights…,” etc, etc, The solution, Geddes suggested, was on display in the Futurama exhibit. Geddes would also follow up on Futurama the next year with a detailed book titled, Magic Motorways.

Given the Geddes-GM introduction of the wonders of freeways yet to come, America was primed for a new world of unimpeded, care-free auto travel, even through cities. The GM exhibit, one scholar suggested, “stimulated public thinking in favor of massive urban freeway building.”

Paved highways by this time already existed, with a few parkways and private highways dating to the early 1900s. Parkways in the New York city and Long Island area came on in the 1930s. In terms of highways between states, the famous “Lincoln Highway,” U.S. Route 30, the nation’s first transcontinental highway, a two-lane roadway, was completed in 1935.

U.S. Route 66, another of the original U.S. highways, would run more than 2,400 miles from Chicago, IL to Santa Monica, CA. That road was first initiated in 1927 but was not completely paved until 1938.

In Pennsylvania, the 164-mile Pennsylvania Turnpike, opened in 1940, was the first four-lane, limited access highway in the U.S. It was the first to feature no cross streets, no railroad crossings, and no traffic lights. It included a 10-foot median strip and a 200-foot total right-of-way. Each lane was 12 feet wide. Its design and engineering became an important model for the Interstates and freeways that followed.

In 1944, funds were designated for primary, secondary, and urban roads for the first time, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt then supported a 40,000 mile interregional system of interstate highways with the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944, but no funding was then secured for that system.

After Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected president in November 1952, support for a nationwide system of interstate highways grew. Eisenhower’s previous trek across America as a young army officer in 1919 had left an impression, as did his experience in Europe during WWII as the Allies supreme military commander, witnessing how easy it was to move military vehicles on the German autobahn, the world’s first “superhighway.” Eisenhower backed the completion of a 41,000 mile network of high-speed interstate highways across the nation – in part as a national defense measure during the Cold War. By 1955, the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads (then in the Department of Commerce) released the “Yellow Book”—a national blueprint to build out the 41,000-mile Interstate Highway System. The series of maps laid out the proposed routes for the massive project.

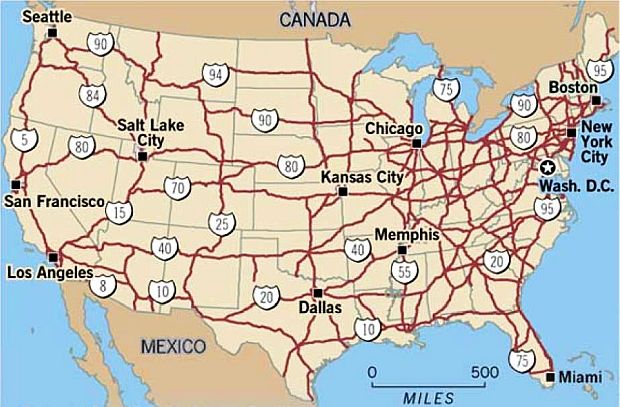

Map showing the Interstate Highway system as of 2006, fifty years after its authorizing legislation – at 46, 837 miles. This map gives a broad overview of the system, and does not provide detail on segments running through or around metro areas, or segments that were blocked, abandoned, or otherwise not completed.

On June 29,1956, Eisenhower signed into law, the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 which set in motion the massive interstate highway road-building program for the 41,000-mile network. The limited-access highways would link 90 percent of all cities with populations of more than 50,000. The Federal Government would shoulder 90 percent of costs and would distribute tens of billions in road funds among the states over the next few decades. A key breakthrough in paying for the system – and an emerging power base for highway builders – came with the creation of The Highway Trust Fund, an exclusive financing source dedicated only to interstate highways and financed initially from a 3-cents-per-gallon gasoline tax.

The I-10 Interstate Highway in Houston, TX illustrates the extreme, but not atypical urban interstate highway in later years built to accommodate heavy commuter use in metro areas. Houston’s Katy Freeway, as shown here, was widened in 2008 to as many as 26 total lanes, counting six lanes of access or frontage roads –.the world’s widest freeway.

Both praised and lambasted, the Interstate Highway build-out would become one of the world’s largest public works projects ever, making road builders, concrete and asphalt providers, heavy equipment manufacturers, and others jubilant in their windfall. Also happy were those profiting from the auto-industrial growth it stimulated – from cars and trucks, to tires, gasoline, motels, hamburger stands, service stations, trucking, real estate, and more.

On the downside, meanwhile, were the social and environmental costs – not least being a major transformation of the urban and suburban landscapes, smog and automobile pollution, eroding tax base in cities, and displacement of those in the path of freeway construction, quite often African Americans and other communities of color.

In some urban areas, city managers and transportation planners discovered that the generous 90 percent federal funding found in the interstate highway program could be used as a kind of urban renewal program, targeting “blighted areas” for “slum clearance.” Using the highway funds to pay for some of the urban demolition thus became a kind of two-for-one deal.

In fact, for a time, three federal laws – the Federal Housing Acts of 1949 and 1954 and the Federal Highway Act of 1956 – worked in a kind of synchrony reshaping urban areas, and in the process, dislodging thousands of residents and small businesses. More on this later.

Other targets of highway builders in metro areas would be parks or other open spaces, as well as land along rivers or bay areas; corridors that offered lower construction costs, minimal demolition, and seemingly less vocal resistance — but still considerable swaths of urban space.

“What Freeways Mean To You,” a 1950s pro-freeway publication by the Automotive Safety Foundation, formerly the safety division of the Automobile Manufacturing Association.

A major and continuing criticism of the interstate program is that more commuter freeways simply generated more traffic, which in turn generates a demand for more and/or expanded freeway construction. This typically becomes apparent some time after a freeway segment is completed, only to be jammed with traffic congestion a few years later.

But in the mid-to-late-1950s, as the Interstate Highway System was initially rolled out, things went smoothly enough. Highway engineers encountered little opposition from communities in rural areas, and large segments of the system were completed quickly. But when the highway builders tried to expand the network into major cities, that’s when the age of the freeway revolts began.

What follows below is a look at a few of the urban areas where highway battles ensued in the 1950s-1970s time frame, as well as some of the books and other literature that appeared during and after the highway controversies, and which today comprise an important part of that story.

San Francisco

San Francisco was one of the first locations where citizen opposition to urban highway segments began, taking form in the mid-1950s. A road plan for San Francisco developed in the late 1940s by the company of Charles K. DeLeuw, a Chicago engineer, included a series of elevated and subterranean freeways. By 1948, a San Francisco Planning Department map, adopted in 1951, showed plans to build 10 freeways crisscrossing the city. The Bay Bridge was to be connected to the Golden Gate Bridge via the Embarcadero Freeway. As early as 1949, a park commissioner had objected to one proposed freeway encroaching on public park land. And by 1955, residents in the path of the Western Freeway organized in opposition to fight that route, and citizen groups elsewhere in the city were also raising concerns about other segments.

By 1959, the anti-freeway movement in San Francisco came to be known as “The Freeway Revolt.” Neighborhood groups at that time presented the Board of Supervisors with a petition signed by 30,000 people asking to cancel seven of the 10 planned freeways, including the Embarcadero Freeway, 1.2 miles of which had been built with work halted. In 1959, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors voted to cancel seven of ten planned freeways, including an extension of the Central Freeway. Other freeway segments in the city went forward, despite protests, as in the case of Potrero Hill freeway segment.

Picketers at San Francisco City Hall, April 18, 1961 protesting against the Potrero Hill freeway segment (a segment also known as “P-11," the Southern Freeway, and I-280) connecting to the Embarcadero Freeway. San Francisco Public Library.

By 1962, opposition to other California highway projects beyond San Francisco had resulted in formation of a statewide anti-freeway organization called the California Citizens Freeway Association. Claiming 250,000 members, the association sought and won a “cooling-off period” from state leaders who promised that no further steps toward construction of four disputed freeways would be taken until they were discussed at a conference. Among those highways at the time were: one in Chico running through a memorial park; one in Oakland intruding on a college campus; a third in Monterey that threatened scenic values, and the last in San Francisco, the Embarcadero Freeway, then in use, but criticized for cutting off access to San Francisco Bay. The group said it would support legislation for tearing down that freeway.

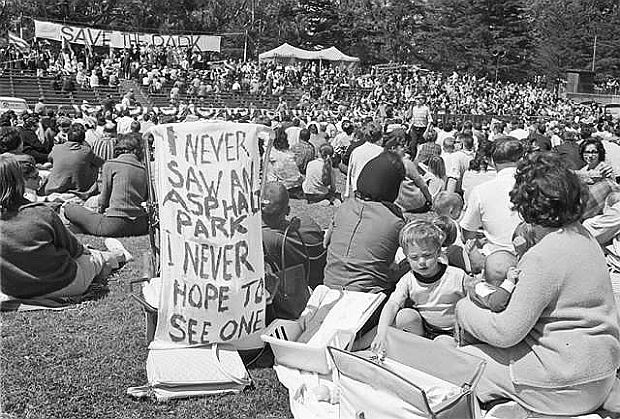

May 17, 1964. Photo of crowd at rally in Golden Gate park to fight the freeways. Folk singer, Malvina Reynolds, famous for her 1962 song, “Little Boxes,” recorded by Pete Seeger and others, wrote and sang an anti-freeway song for the rally titled, “The Cement Octopus.”

Back in San Francisco, meanwhile, 1964 protests against a freeway through the Panhandle and Golden Gate Park led to its cancellation, and in 1966 the Board of Supervisors rejected an extension of the Embarcadero Freeway to the Golden Gate Bridge, and it remained an unfinished and disputed roadway for many more years.

Opposition to the Embarcadero Freeway continued, and in 1985, the Board of Supervisors voted to demolish it. It was closed after sustaining heavy damage in 1989’s Loma Prieta earthquake and torn down shortly thereafter. The entire portion of the Central Freeway north of Market Street was demolished over the next decade: the top deck in 1996, and the lower deck in 2003. Other short freeway segments were demolished in the same time period: the Terminal Separator Structure near Rincon Hill and the Embarcadero Freeway, and the stub end of Interstate 280 near Mission Bay.

New York City

In New York City during the 1950s and 1960s, one of the most powerful public officials was Robert Moses, famous builder of highways, bridges, parks, and other public works throughout the New York metro region.

Moses’ career, which ran from the mid-1920s through the early 1970s, has been written about extensively in Robert Caro’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1974 book, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, and also in the best-selling 2014 artist/ comic-book-style biography, Robert Moses: The Master Builder of New York City, by Pierre Christin and Olivier Balez.

Anthony Flint’s 2009 book, “Wrestling With Moses: How Jane Jacobs Took On New York’s Master Builder and Transformed the American City.” Click for copy.

Earlier, Jacobs had also authored a piece for Fortune magazine in 1958, “Downtown Is for People,” which marked her first public criticism of Robert Moses. But in her later book, The Death and Life of…, she made plain her feeling about the automobile: “Not TV or illegal drugs but the automobile has been the chief destroyer of American communities.”

As a resident of New York’s Greenwich Village, Jacobs had participated in grassroots opposition to Robert Moses’ “urban renewal” and “slum clearance” projects, as well as efforts to protect Washington Square Park from roadway intrusion.

But in the 1960s, Jacobs chaired the Joint Committee to Stop The Lower Manhattan Expressway, a Robert Moses-backed 10-lane expressway planned to carry Interstate 78 from the end of the Holland Tunnel through Lower Manhattan to the Williamsburg Bridge with a connection to the Manhattan Bridge.

The expressway would have been built directly through such neighborhoods as Greenwich Village, SoHo, and the Lower East Side, much of which was characterized as old and “run down” in the mid-20th century. Jacobs continued to fight the expressway as plans continue to resurface in 1962, 1965, and 1968, and she became a local hero for her opposition to the project.

After a long battle, the expressway was canceled in the 1970s by then New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller due to fears of increased pollution and negative effects on such cultural neighborhoods as Little Italy and Chinatown.More detail in the Jacobs-Moses fight is found in Anthony Flint’s 2009 book, Wrestling With Moses: How Jane Jacobs Took on New York’s Master Builder and Transformed The American City.

Dozens of other freeways and/or freeway extensions throughout the New York metro region were also challenged or stopped over the years, a number of which are listed at Wikipedia’s page on “Highway Revolts in the United States.”

Another famous long-running freeway battle in New York was that of the Westway Highway, a fight which included some determined litigation and tireless citizen opponents, among them, public interest advocate, Marcy Benstock.

For more detail on that battle, see William Buzbee’s 2014 book, Fighting Westway: Environmental Law, Citizen Activism and The Regulatory War That Transformed New York City.

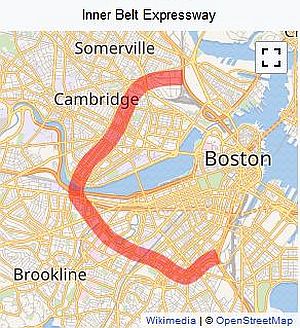

A Wikipedia map of the proposed Inner Belt Expressway of Boston, MA in the 1960s, which would have been designated Interstate 695 had it been built.

In 1948, inspired by changes to federal law, Massachusetts government officials started hatching plans to build multiple highways circling and cutting through a number of Boston communities. The plans made steady progress through the 1950s.

Part of the plans included The Inner Belt, which would have been designated as part of the Interstate System as I-695. It would have circled through Boston and adjacent areas, passing through communities including Roxbury, Cambridge, and Somerville, eventually connecting to I-93.

But when officials began to hold public hearings in 1960, and it became clear what this plan would entail, including a disproportionate impact on poor communities, the people pushed back. Activists, many with experience in the civil rights and antiwar protests, began to organize.

Meanwhile, swathes of Roxbury had been cleared out to make way for the highway, displacing residents, as protesters organized and started posting signs around town that read, “Stop the Belt”.

On January 25, 1969 — just days after Governor Francis W. Sargent’s inauguration — some 2,000 people gathered on the State House steps to protest the highway. In December 1970, Sargent declared a moratorium on the highway project, and by 1972, the plan for the Inner Belt system had been shut down entirely. The federal funding originally intended for it was instead directed to expansions of public transit through new provisions of law in subsequent highway acts.

Governor Francis W. Sargent spoke to the gathering of Inner Belt dissenters during a January 25, 1969 protest outside the State House. Photo, Associated Press.

As the Boston Globe would later report, quoting Sargent in a 1972 televised speech: “We will not build the expressways… In the end. . . we will have created a real and workable alternative to the increasingly damaging use of the automobile.”

There are at least two books, and a number of newspaper stories, on the history of the Boston battle over the Inner Belt. Three authors – Alan Lupo, Frank Colcord, and Edmund Fowler – combined efforts to produce the 1971 book, Rites of Way: The Politics of Transportation in Boston and the U.S. City (Little Brown). This book covers the Boston fight and also other highway issues in its review of U.S. urban transportation planning and decision making.

Karilyn Crockett in her 2018 book, People Before Highways, offers her take on the social, political, and environmental significance of the Boston anti-highway protest and its national implications. Amazon describes her book as: “…The story of how an unlikely multiracial coalition of urban and suburban residents, planners, and activists emerged to stop an interstate highway is one full of suspenseful twists and surprises…. And yet, the victory and its aftermath are undeniable: federally funded mass transit expansion, a linear central city park, and a highway-less urban corridor that serves as a daily reminder of the power and efficacy of citizen-led city making.”

Writers & Critics

Also contributing to the public critique of the Interstate Highway program during the 1950s-1970s were a number of academic historians, professional architects, and journalists.One prominent early critic in this group was historian and urbanologist Lewis Mumford who would take up his pen against the urban intrusion of highways in books and essays. One of the latter, “The Highway and The City,” was a critical broadside he wrote in April 1958 that first appeared in Architectural Record. In later years, some books by Mumford using this title were also issued, as shown at right. Meanwhile, his 1962 book, The City in History, won the 1962 U.S. National Book Award for nonfiction.

Mumford also appears to have played a role in organizing one of the first anti-highway conferences among academics critical of the new Interstate Highway program. In September 1957, a conference titled “The New Highways: Challenge to the Metropolitan Region,” was sponsored by the Connecticut General Life Insurance Company and held in Hartford, CT. It was among the first formal confrontations between academic critics and the highway builders, receiving favorable press coverage at the time. Mumford, for his part, said that the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 “was jammed through Congress so blithely and lightly… because we Americans have an almost automatic inclination to favor anything that seems to give added attraction to the second mistress that exists in every household…: the motor car.”

Other writers and academics also added new perspectives that were critical of, or otherwise illustrated new thinking about, locating and building highways and/or transportation planning in metropolitan areas. Among these was Daniel P. Moynihan, a professor at Harvard University who wrote an April 1960 article in The Reporter titled, “New Roads and Urban Chaos.” Moynihan, who would later become a special advisor or urban affairs to President Richard Nixon in the early 1970s, and later, a U.S. Senator, was no fan of metropolitan freeways. Historian Raymond Mohl has noted that Moynihan:

“…had written critically about the interstate system and about the lack of metropolitan transportation planning, especially for mass transit, calling it ‘lunatic’ to ‘undertake a vast program of urban highway construction with no thought for other forms of transportation’. Moynihan also disparaged the prevailing automobile culture: “More than any other single factor, it is the automobile that has wrecked the Twentieth-Century American city, of use, dissipating its strength, destroying its form, fragmenting its life.”

Helen Leavitt’s 1970 book, “Superhighway-Superhoax,” became an important source book on the politics of highway building & the Highway Trust Fund. Click for copy.

Academics and other writers added related books and articles, including: William H. Whyte, who wrote the 1968 book, The Last Landscape; Ian McHarg, whose 1969 book, Design With Nature, pioneered the concept of ecological planning, also wrote, “Where Should Highways Go?” earlier in an April 1967 Landscape Architecture piece; and Herbert Gans, a sociologist who would write a number of books, including one in 1968 titled, People & Plans: Essays on Urban Problems & Solutions.

However, one of the first hard-hitting popular critiques of urban freeways came from a Washington, D.C. journalist named Helen Leavitt. Her book, Superhighway– Super-hoax, published by Doubleday in 1970, would have a galvanizing effect on activists, and also, grudgingly, on some policymakers as well.

Leavitt, who had written for several major newspaper and magazines in her career, was moved to write the book when her Washington D.C. home was targeted for an urban freeway route. In that process, she had also been a party to a 1968 lawsuit opposing D.C. freeway construction.

But her 1970 book – with a cover tagline that described the nation’s highway system as “a concrete straightjacket that pollutes the environment and makes driving a nightmare” – became one of the first critical investigations of the Interstate Highway Program, its deep-pocketed lobby, “the road gang,” and its gold-mine funding system, the Highway Trust Fund.

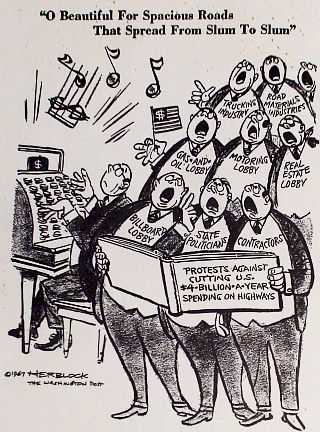

1967 cartoon by the Washington Post’s “Herblock,” took aim at the high-powered “road gang” singing in chorus to protect cuts to their highway-building funding largesse.

Leavitt revealed, for example, that one of these special interest groups at the time, the American Road Builders Association, boasted 5,300 members and was made up of highway contractors, construction firms, engineering colleges and even some members of Congress. She also salted her narrative with lots of traffic and highway-building statistics as well as detail on the machinations of the road gang in Congress.

Leavitt opposed the Highway Trust Fund; believed that trust funds were generally bad public policy, and urged that it be abolished. All auto-tax revenues, in her view, should be put into the general treasury and that highway needs should have to compete fairly with all other national needs.

Leavitt would testify before Congressional committees to share her views on how highway and transportation policy should change, and her book became something of a guiding source to citizens and activists battling highways in their own communities.

In 1996, the New York Public Library included Leavitt’s book among the best books of the 20th century, noting: “The book’s argument and central paradox, that most superhighways bring increased traffic congestion rather than less, has never been effectively countered.” The citation also singled out some of her criticisms, “most notably, she demonstrates environmental degradation, strangled cities, and ruined public transportation systems.”

1972, “Highyways to Nowhere”. |

|

There were also several other books that came out in the 1969-early-1970s period, each offering critiques of the nation’s highway program or “car culture” in one form or another:

A. Q. Mowbray’s Road to Ruin: A Critical View of the Federal Highway Program, was published in 1969 (Lippincott);

The Pavers and the Paved: The Real Cost of America’s Highway Program (D.W. Brown), by Ben Kelley came out in 1971;

The Great American Motion Sickness (Little Brown, 408pp), appeared in 1971 and was written by John Burby, a former newspaper reporter who had worked as a special assistant to Transportation Secretary Alan Boyd;

Autokind vs. Mankind, by Kenneth R. Schneider, was also published in 1971 (Norton, 268pp,); and,

Highways to Nowhere: The Politics of City Transportation, by Richard Hébert (Bobbs-Merrill), was published in December 1972.

In that book, Hébert examines highway controversies in five cities – Flint, Michigan; Dayton, Ohio; Indianapolis, Indiana; Atlanta, Georgia; and Washington, D.C.

Changing Law

After ten years of the interstate highway program, by 1966, more than 15,000 miles of highway had been built across the U.S. But there had also been some changes in transportation law and highway planning by way of subsequent federal highway acts that made the highway siting and planning process a bit more sensitive to the public interest. By 1965, metro areas had been required to have comprehensive transportation plans. And after 1966, parks, recreation areas, and historic sites could not be taken for a highways if feasible alternative routing existed – a provision of law that would later be upheld in litigation (more on this later). The urban and metropolitan segments of the interstate system, meanwhile, remained the toughest and most contentions for highway builders.One survey conducted by the U.S. DOT between 1967 and 1968 recorded 123 separate highway revolts and road-related protests across the country. One survey conducted by the U.S. Department of Transportation between 1967 and 1968 recorded 123 separate highway revolts and road-related protests across the country.

There were also some new leaders coming into the federal highway program who brought a change in outlook. Alan Boyd became the first U.S. Secretary of Transportation in November 1966. According to historian Raymond Mohl, Boyd brought a new perspective in part: “Speaking in California in 1967, Boyd must haves shocked his audience of transportation experts by stating, ‘I think the so-called freeway revolts around the country have been a good thing.’ He elaborated by urging more citizen involvement in highway decision making and advocating a balanced transportation system. In another speech in 1968, Boyd asserted that expressways must be ‘an integral part of the community, not a cement barrier or concrete river which threatens to inundate an urban area’.” Many state highway administrators, however, were still old school in their outlook and very powerful in terms of the financial leverage and patronage they held through the interstate program.

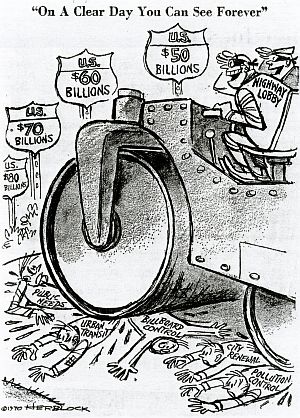

1970 Herblock cartoon shows highway lobby, then at tens of billions in funding, “steamrolling” other interests – urban transit, city renewal, and pollution control among them. But changes were on the way to stop destructive urban freeways and help fund mass transit.

But one big change in the 1970s that was about to come down on the highway builders was the emerging national concern over pollution and environmental protection.

In early 1969, an offshore oil spill off Santa Barbara, California and the pollution-fueled burning of the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, Ohio helped spur a new environmental fervor across the country. A year later, in January 1970, President Richard M. Nixon signed The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) into law.

Sometimes called the Magna Carta of the nation’s environmental laws, NEPA required federal agencies to consider environmental impacts before taking action on federal programs, in some cases, preparing detailed environmental impact statements on the proposed action, and including possible alternative options.

So by the 1970s, a whole new ball game was ahead for federally-funded public works projects, highways among them.

Earth Day 1970

Green Power

The environmental movement in America had been building in strength and influence since the 1950s. With Earth Day on April 22, 1970, the movement reached a critical mass of popular support and burst onto the national scene. On that day, twenty million people across the country participated in peaceful demonstrations and teach-ins. Earth Day organizer, U.S. Senator Gaylord Nelson, called it a “truly astonishing grass-roots explosion.” Among concerns of some environmentalists was automobile pollution and the explosion of highway projects, a sentiment expressed, in part, by folk singer Joni Mitchell and her 1970 hit, song, “Big Yellow Taxi,” with the line: “…They paved paradise and put up a parking lot.”

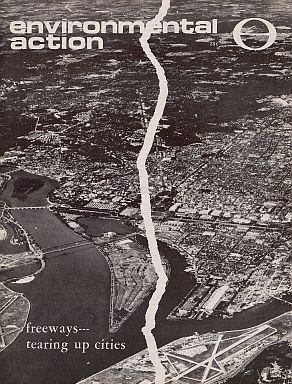

October 17, 1970 edition, with cover story in this issue focusing on “Freeways - Tearing Up Cities.” |

May 29, 1971 Environmental Action magazine with cover story featuring “ Freeway Folly”. |

One public interest group founded in April 1970 by Earth Day activists to focus on environmental issues and national politics in Washington, D.C. was a group named Environmental Action. An important arm of the group was its lean, no-frills magazine, Environmental Action, reporting on the issues and politics of the day from Washington – including highway battles of that era. And in later years, the Environmental Action Foundation would contribute to publications such as, The End of The Road: A Citizen’s Guide to Transportation Problem-Solving.

In 1971, Environmental Action and several other organizations launched the Highway Action Coalition (HAC) with the purpose of reforming the federal Highway Trust Fund so that federal funds could be used for mass transit and other non-highway transportation projects.

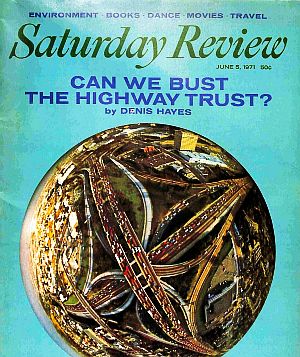

June 1970. Earth Day co-founder, Denis Hayes, wrote the cover story, "Can We Bust The Highway Trust?", appearing in "Saturday Review" magazine.

One of the Earth Day organizers and leading environmentalists at that time, Denis Hayes, would also write a June 1971 cover story for Saturday Review magazine titled, “Can We Bust the Highway Trust Fund?”

Environmental Action and the Highway Action Coalition lobbied Congress for changes in the Highway Trust Fund, and there was also movement elsewhere expressing support for change in how the Trust Fund could be used.

In March 1972, no less a voice that than of Secretary of Transportation John A. Volpe asked Congress to let cities and states spend several billion Trust Fund dollars over a period of years for urban mass transit projects. Earlier, in the fall of 1971, the Gulf Oil Corporation endorsed a proposal for using Massachusetts highway funds for mass transit. And in January 1972, Henry Ford II, of the Ford Motor Co. announced that he favored using some Federal highway money for public transportation.

Oct 1970 ad by Ford and ATA urging the completion of "gaps" in the Interstate Highway System.

On the Trust Fund, meanwhile, by August 1973, after arduous battles in Congress, President Richard M. Nixon signed into law the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1973 that gave local officials the option of using some Highway Trust Fund revenue for rail transit.

The highway wars, however, were not over by any means. Dozens of battles across the country were ongoing through the 1960s and 1970s. Among them was the one in metropolitan Washington, D.C. region, which because of its unique political, geographic and oversight situation, involved the states of Virginia and Maryland and the U.S. Congress, as the latter controlled District of Columbia funds through Congressional appropriations.

The D.C. Fight

In the 1950s-1970s period, there was a plan to build a complete freeway system within the District of Columbia, with urban segments connecting to the national interstate highway system. The plan underwent several revisions, but by the mid-1960s and early 1970s it began to come up against a determined base of citizen and community resistance. This citizen revolt was unique in a number of ways, not least of which was the breadth of the DC-wide citizen coalition that emerged – rich and poor, black and white, young and old – but also for the political gauntlet it ran, facing members of Congress and the White House at times, as well as litigation reviewed by the U.S. Supreme Court.

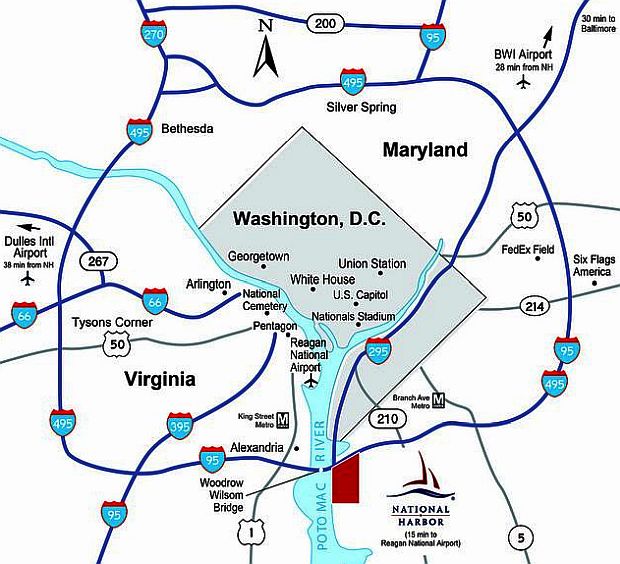

General reference map of major highways that now exist in the Washington, DC metro area, with the state of VA to the left of the Potomac River, and the state of MD to the right. Some of the major interstates in the region, such as I-95 from the Maryland side, and I-66 from the VA side, were once planned to enter D.C.

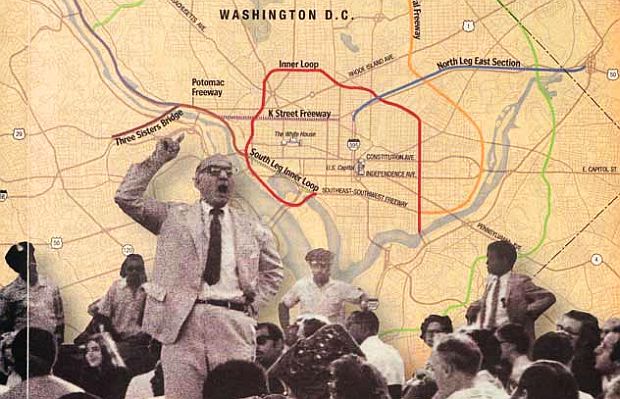

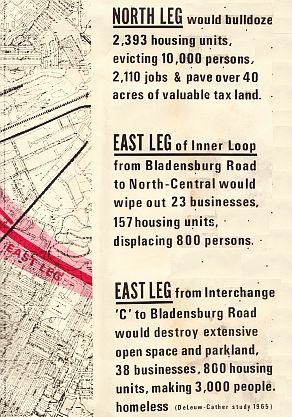

Various Interstate Highways – among them, I-95 from Maryland and I-66 from Virginia – were proposed to enter D.C., some given local names inside the District, along with freeway spurs and various “legs.” There was also a major Potomac River bridge crossing proposed that would bring commuter traffic into the District from Arlington, VA – the Three Sisters Bridge (I-266). All of these elements, with variations and “inner loop” style highways, amounted to some 30-to-40 miles of proposed freeways converging on a relatively small geographic area with established neighborhoods. Other difficulties for prospective freeway construction in the District would involve potential impacts on the national monuments and review by the National Capital Planning Commission.

December 1968. Sammie Abbott in action. |

1972. Angela Rooney, a Brookland DC resident. |

1970. Reginald Booker before DC City Council. |

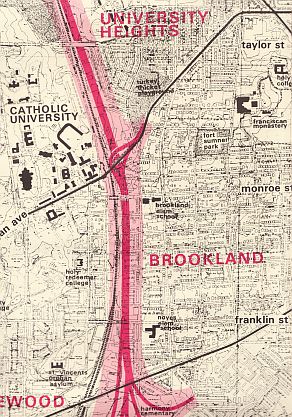

Highway plans for the District of Columbia dating from 1959 had indicated a series of freeways traversing a number of established neighborhoods. In 1965, a Takoma Park, MD resident named Sammie Abbott discovered that his house was in the path of one of the proposed freeways– at least one of which had been shifted from the white Northwest quadrant of DC to the predominantly black Northeast quadrant. (Takoma Park is on the D.C. border, on the Maryland side of Northeast Washington, DC.)

Abbott, then in his 50s, and having been a union organizer and civil rights activist, was not a man accustomed to sitting still for any outside infringement on his life or community. It was about then that he and others would form a small core group that would later found a broader, city-wide umbrella group of citizen activists to fight DC freeways — the Emergency Committee on the Transportation Crisis (ECTC).

Among the early joiners and founders of ECTC were Tom and Angela Rooney of the Brookland Neighborhood Association, also in the path of a proposed Northeast freeway. The Rooneys lived in Brookland not far from Catholic University where Tom was a faculty member.

Abbott later added others in the path of the Northeast freeways, including Simon Cain of Lamont-Riggs Citizens’ Association. Cain was an African-American lawyer who graduated from Howard University. He would serve as ECTC’s first Chairman and Angela Rooney its secretary. As noted in the dissertation of Gregory Borchardt (see Sources), Tom Rooney, at one public meeting on the freeways in 1967, explained ECTC’s position: “We will not accept freeways. They are being used as instruments of racial injustice.” ECTC called for a complete moratorium on freeway building until studies on their full impact were completed. They wanted all highway construction postponed until the planned mass transit subway system was built.

In 1960 the federal government created the National Capital Transportation Agency to begin planning a rapid rail system for the DC metro area and nearby suburbs – a planning power later transferred to the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA). Activists like Abbott and others in ECTC, as well as some local politicians, viewed the transit system proposal as a way to block freeways and divert the highway money to subway construction.

Abbott would also recruit Reginald Booker, an African America resident, civil rights and anti-Vietnam War activist, then living near Howard University, an area of DC also affected by the proposed freeways. Booker, who had also served in the U.S. Army, was then a clerk for the federal government at the General Service Administration. He later became ECTC’s chairman, with Abbott serving primarily as the group’s strategist and often its passionate spokesman. Booker and Abbott, over the years, would be arrested multiple times during the DC freeway fight.

In February 1968 after Booker was elected chairman of ECTC he began recruiting other black leaders into the group, including Charles Cassel of Black United Front and Marion Barry of Pride, Inc. Barry would later become DC Mayor. By late 1968, ECTC meetings routinely began to attract turnouts of 200 or more citizens. From 1968 to 1972, ECTC conducted more than 75 street protests. A number of neighborhoods throughout Northeast DC would be impacted by planned highway segments such as the North Central and Northeast freeways.

February 1965. Sammie Abbott (at far right near policeman), with contingent of citizens demonstrating against freeways, but supporting rapid transit for DC Metro region. Photo by Walter Oates / DC Public Library, Star Collection, Washington Post.

Sammie Abbott, as ECTC’s chief strategist, typically organized pickets before local meetings, as shown above. But Abbott could also be quite theatrical in his appearances at public meetings, whether before local government or Congressional committee. At local meetings, he often climbed up and stood on a chair in the audience so he couldn’t be missed, booming out his critique in a loud voice.

At one DC meeting in December 1967 in the Brookland neighborhood, as noted by Gregory Borchardt, Abbott jumped on stage and pointed a finger at the DC mayor, accusing him of failing to use his political clout to save neighborhood homes confiscated for a freeway right-of-way. At the same meeting a group of ECTC members began a recitation of their version of “America the Beautiful” (no doubt a Sammie Abbott-encouraged tactic, if not his verse as well):

O Beautiful for Spacious Roads that Spread from Slum to Slum,

The smog is gray, the homes decay, but see the profits come.

Suburbia, Suburbia, there’s profit there to glean.

Pollute the air, but they don’t care, they’re selling gasoline.

Oh beautiful for Interstate, For glorious 90-10.

Don’t heed the people’s picket signs, but just cement them in.

America, America, Ford shed his grace on thee.

Black and white, unite and fight, to defeat High-way Lobby.

Portion of illustration with highway map background used in Nov. 2000 Washington Post magazine story on DC freeway history by Bob & Jane Levey, showing DC meeting with Sammie Abbott (standing at left) and others.

ECTC, meanwhile, did its homework on the proposed freeway routes, and often prepared detailed information for citizens and the media. One large poster prepared for city-wide distribution used the title, “Freeway Cancer Hits DC,” with a smaller headline that read, “Unite to Defend Your Homes, Community, City, Parkland And The Air You Breathe.” This poster offered neighborhood-by-neighborhood snapshots along the various proposed freeway routes listing the impacts in terms of homes and business losses (segments shown below are separate samples, not shown in sequence).

1970: Portion of “Freeway Cancer Hits DC” poster showing highway segment & neighborhood detail. |

1970. Another portion of ECTC poster, provid-ing data on some resident & business impacts. |

Much of this portion of the DC highway fight was on the Maryland side of the District and in the Northeast quadrant of D.C., with predominantly African American communities. The highway route that had first incensed Abbott and threatened his home – the North Central Freeway – had been shifted from the predominantly white Northwest DC quadrant, west of Rock Creek Park, to the predominantly black Northeast quadrant of DC. In 1966, after the National Capital Planning Commission voted to approve the North Central Freeway, Abbott, as Gregory Borchardt has noted, told the DC media that he planned to mobilize black power along with white power to battle the freeways. By 1967 he had indicated a plan to work with, among others, nationally-known black activists, like Stokely Carmichael, on parallel actions “to stop the institutional racism of the highway and urban renewal planners.”

[Note: “DC Fight” story continues below sidebar].

|

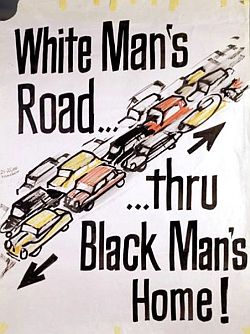

Highways & Race  Poster of phrase adopted from 1967 testimony of Sammie Abbott in Washington, DC during freeway protests. In January 1967 testimony before the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) on the North Central Freeway, Sammie Abbott used the phrase, “a white man’s road…through black men’s homes.” His partner at ECTC, Reginald Booker, picked up on Abbot’s remark, turning it into a slogan for ECTC to use to galvanize black opposition to the freeways. Abbott, who was also a graphics artist, produced dozens of posters and flyers that featured the phrase. Generally, however, the label of “White Men’s Roads Through Black Men’s Homes,” was appropriate for dozens of other cities where freeways during the 1950-1970s era were also routed through African American and other minority communities. As urban historian Raymond Mohl has noted: ….Massive amounts of urban housing were destroyed in the process of building the urban sections of the interstate system. By the 1960s, federal highway construction was demolishing 37,000 urban housing units each year; urban renewal and redevelopment programs were destroying an equal number of mostly-low-income housing units annually. The amount of disruption, a report of the U.S. House Committee on Public Works conceded in 1965, was astoundingly large. As planning scholar Alan A. Altshuler has noted, by the mid-1960s, when interstate construction was well underway, it was generally believed that the new highway system would “displace a million people from their homes before it [was] completed.” A large proportion of those dislocated were African Americans, and in most cities the expressways were routinely routed through black neighborhoods. The two photos below show a predominantly African American neighborhood in Detroit, Michigan — the first photo, from the 1950s, shows the scene “before” the freeway arrived, and the second, about 1962, “after” the freeway arrived.  Mid-1950 photo showing the Hastings Street area of Detroit, MI, (looking north and east ) which was then an active small business strip that catered almost exclusively to the African American community, also a center for Detroit blues and R&B (photo, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University).  Photo taken around 1962 with somewhat broader view of approximately the same Hastings Street area (use black-topped steeple at center as rough marker), as the Interstate highway segment I-75 / I-375 is constructed through the area. (photo, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University). Below is a listing of some examples of cities where minority communities were sliced through, bisected, or completely destroyed by urban freeways. These examples, mostly from the 1950s-1970s period, are culled from the published works of Raymond Mohl, Olivia Paschal, Dan Albert, Nithin Vejendla, and others as indicated parenthetically here and attributed with full citations at the end of this story in “Sources”: **In Miami, Florida I-95 was routed through the Overtown neighborhood. One massive expres-sway interchange there took up forty square blocks and demolished the black business district and the homes of some 10,000 people. By the end of the 1960s, Overtown had become an urban expressway wasteland. Little remained of the neighborhood, known as the Harlem of the South.” [Mohl] **In New York City, the Cross-Bronx Expressway gouged a seven-mile trench through a primarily lower- middle-class Jewish community, ripping through a line of apartment houses and dislocating thousands of families and small businesses. [Mohl] **In Cleveland, a network of expressways displaced some 19,000 people by the early 1970s. [Mohl] **In Pittsburgh, PA, a three-and-a-half-mile inner-city expressway forced 5,800 people from their homes. [Mohl]. **A Kansas City, Missouri, midtown freeway was routed through a Model City area and nearby neighborhoods, ultimately destroying 1,800 buildings and displacing several thousand residents. [Mohl]. **In Baltimore, Milwaukee, Indianapolis, and St. Paul, expressways plowed through black communities, reducing thousands of low-income housing units to rubble. [Mohl] **In Camden, New Jersey, Interstate 95 cut through the mostly black city, displacing nearly 1,300 families. [Albert ] **In New Orleans, highway builders leveled a wide swath along North Claiborne Avenue, at the center of an old and stable black Creole community, which included a long stretch of old oak trees. North Claiborne Avenue served a variety of community functions, festivals, and parades. By the 1970s, I-10’s massive elevated highway had been built through the devastated Treme community. [Mohl] **In Durham, North Carolina, construction of state Highway 147 in the late 1960s cut through the historically black community of Hayti, displacing more than 500 black families. [Paschal] **In Little Rock, Arkansas, city planners bulldozed the black business district on 9th Street to construct Interstate 630, demolishing businesses and uprooting at least 695 black families in the High Street neighborhood. [Paschal] **In Detroit, the Chrysler Freeway was routed through Paradise Valley and Black Bottom, destroying a vibrant black business and entertainment district that contained some of the African-American community’s most important institutions. The Lodge Expressway (M-10) cut through the increasingly black neighborhoods around 12th Street and west of Highland Park, and the Edsel Ford Freeway (I-94) managed to cut through both the black west side and the northern extension of Paradise Valley.. The Ford Freeway displaced 2,800 buildings by the 1950s in the??. Black Bottom, which had become home to 300 Black-owned businesses by the 1930s, was completely gutted. [Vejendla] **In Winston-Salem, North Carolina, U.S. Route 52 sliced through East Winston, where 100 percent of the 1,594 families known to have been displaced by construction were black. [Paschal] **In Houston, Interstate 288 was built straight through the Third Ward, an historically black neighborhood. [Paschal] **The Richmond, Virginia neighborhood of Jackson Ward, which also claimed a “Harlem of the South” attribution, was bisected and destroyed by I-95. [ Albert ] **Highways also cut through black communities in Birmingham and Montgomery, Alabama, and Columbia, South Carolina. [ Albert ] **In Cincinnati, Ohio, I-75 razed the mostly black West End. [ Albert ] **In Nashville, Tennessee, after Interstate 40 was routed through a black community there, residents sued, claiming racial discrimination and won a temporary restraining order, but ultimately lost and the highway was built. [ Albert ] **In Los Angeles, the community of Beverly Hills defeated a highway project in 1975 that would have run through its center. However, the heavily Hispanic area of Boyle Heights had six freeways slice through the neighborhood over the years, including two massive interchanges less than two miles apart. [ Eric Jaffe ] **And writing in the New York Times Sunday Magazine in August 2019, Kevin Kruze has observed: “While Interstates were regularly used to destroy black neighborhoods, they were also used to keep black and white neighborhoods apart. Today, major roads and highways serve as stark dividing lines between black and white sections in cities like Buffalo, Hartford, Kansas City, Milwaukee, Pittsburgh and St. Louis. In Atlanta, the intent to segregate was crystal clear. Interstate 20, the east-west corridor that connects with I-75 and I-85 in Atlanta’s center, was deliberately plotted along a winding route in the late 1950s to serve, in the words of Mayor Bill Hartsfield, as ‘the boundary between the white and Negro communities’ on the west side of town. Black neighborhoods, he hoped, would be hemmed in on one side of the new expressway, while white neighborhoods on the other side of it would be protected…” |

Back in Washington, D.C., meanwhile, the freeway protest continued in the late 1960s, now with a broadening base of citizen opposition – a function of where other freeway segments were then being planned.

A key driver of the freeway plans for the District of Columbia was coming from the west; from the Virginia side of the metro area, primarily by way of the proposed Three Sisters Bridge crossing of the Potomac River from Arlington, Virginia. Named after the Three Sisters Islands in the middle of the Potomac River — three small, boulder-type islands — the bridge would carry Interstate I-66 commuter traffic from the Virginia suburbs into DC, landing north of Georgetown. The bridge proposal, in various forms, had been around since the late 1940s, but by the mid-1960s with the Interstate Program, it was now a six-lane crossing, designated as I-266, with affiliated freeway attachments, upgrades, and interchanges on the DC side of the Potomac, feeding into yet other freeways cutting across town as well as down-river, near the Lincoln Memorial and beyond, with possible linkage to DC’s Southwest Freeway.

Three Sisters Bridge proposal, crossing the Potomac River from Arlington, VA, looking east into Washington, D.C., landing on river banks there (not far from Georgetown University, upper right), where it was proposed to connect with other freeway upgrades and interchanges, essentially carrying Virginia commuters into DC.

Residents on the receiving side of this proposal, principally those in upscale Georgetown, Foxhall, and the Northwest quadrant of the District, were discovering these and other freeways in their neighborhoods. Among these residents was Peter Craig, an attorney, chairman of a local group, the Northwest Committee for Transportation Planning, later connected to other groups, such as the Committee of 100 on the Federal City, which consisted of elite and influential players throughout the city. These groups favored mass transit and opposed the Three Sisters bridge, and used their influence to slow or redirect some of the DC freeway proposals — including the North-Central Freeway, a route first planned to run from the Georgetown waterfront up through Glover-Archbold Park in Northwest DC and out Wisconsin Avenue to Bethesda, Maryland, where it would join what is now Interstate 270. In the early 1960s, Craig and friends had won a five-year ban on freeways west of Rock Creek and north of M Street. That resulted, in part, in shifting routes like the North-Central Freeway to Sammie Abbott’s neighborhood and predominantly black communities in Northeast DC. Abbott knew Peter Craig and had earlier done some work for him. By the late 1960s, however, Abbott let Craig know he was angry about freeways being shifted to black Northeast communities, and urged Craig to take a broader city-wide stance on the freeway fight. Craig agreed, becoming a key ally in the ECTC fight, especially on the legal front.

Graphic art depicting Three Sisters I-66 traffic from Virginia "polluting" Washington, DC. ( art by Sammie Abbott ). |

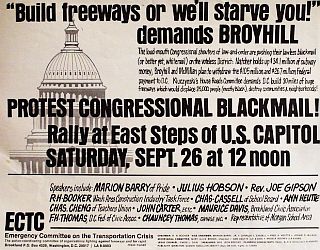

1969. Sample protest flyer and “call-to-Capitol-rally” offered by black activist members of ECTC protesting the “build-freeways-Congressional-blackmail” move by Rep. Natcher and others. |

Still, DC freeway opponents, be they rich or poor, black or white, had another problem: the U.S. Congress. The District of Columbia was not its own political actor. By 1967 it had limited home rule with an appointed mayor and city council. Yet the city was still under the thumb of Congress for its funding, subject to the Congressional Appropriations process.

The congressional D.C. Subcommittee on Appropriations was run in those days by U.S. Rep. Bill Natcher (KY). Natcher, it turned out, was on the side of the DC highway plan, and he wanted all of it – all 38 miles of freeways and especially the Three Sisters Bridge from Virginia.

As Harry Jaffe would put it in his 2015 Washingtonian magazine story:

“Natcher pinned his hopes on the Three Sisters Bridge. He figured that, once built, it would break open the gate for the rest of the [DC] highways. And he had a card to play: The newly formed Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority had recently approved plans for a 97-mile regional Metrorail system. It was up to Natcher’s committee to appropriate funds. Natcher put down his marker. No Three Sisters Bridge, no Metro funds.”

In 1968, Natcher refused to release funds for Washington’s share of Metro unless construction began on the freeways and the Three Sisters Bridge. DC’s black activists, including Marion Barry Jr., then a member of ECTC and later DC mayor, denounced Natcher as a “racist congressman” who was trying “to blackmail the city.” ECTC activists, including Barry, Julius Hobson, ECTC’s Reginald Booker and others, helped organize rallies at the Capitol protesting Natcher’s move and other Virginia and Maryland members of Congress who were supporting the Three Sisters Bridge and the DC freeway plan.

In August 1969, however, the DC Council, which had been leaning toward blocking the bridge, voted to comply with the Federal Highway Act of 1968, succumbing to Natcher’s threat, thereby approving the Three Sisters Bridge, the North Central Freeway, and several other freeways. In return, the city’s subway money would no longer be blocked. The DC freeway activists were incensed, and the DC Council meeting devolved into a fracas. Sammie Abbott and Reginald Booker were among 14 arrested at that meeting.

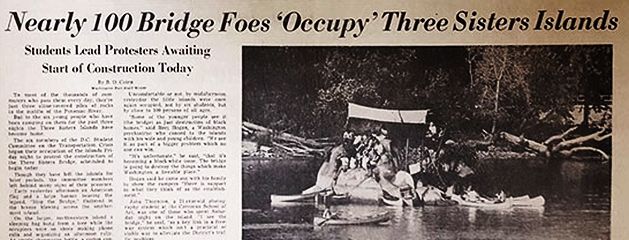

October 13, 1969 story from The Washington Post, front page of the "City Life" section, reporting on college students' Three Sisters Bridge protest, with an occupation of one or more of the Three Sisters Islands in the middle of the Potomac River.

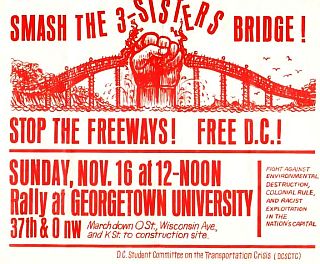

Following the Three Sisters Bridge approval, some construction began on river footings for the bridge in September 1969. But that’s when another contingent of opponents emerged: college students from Georgetown and George Washington universities. A white student organizer — Matt Andrea, who had been on the Georgetown crew team and was familiar with Potomac River and Three Sisters islands — had contacted Sammie Abbott about coordinating efforts, and soon the students joined the fight.

1969 poster announcing Three Sisters Bridge protest rally.

Meanwhile, Peter Craig had gained some legal traction in the courts. In February 1968, when U.S. Court of Appeals ruled the DC highway plans illegal because of a failure to comply with planning procedures. A further lawsuit on behalf of the DC Federation of Civic Associations against U.S. Transportation Secretary John Volpe, alleged that politics had prompted decisions on the Three Sisters Bridge, not the legally-required needs assessment and consideration of alternatives. In late August 1970 the U.S. District Court agreed and ordered a halt to construction. Congress meanwhile, in December 1971, voted to release DC subway funds in a final rebuke to Natcher. On Three Sisters, Richard Nixon ordered the Justice Department in 1972 to appeal the earlier District Court case to the U.S. Supreme Court seeking to overturn that ruling, but the Supreme Court allowed the District Court ruling to stand. Over the next few years there would be a bit more maneuvering and politics involved, but the DC freeway plan and Three Sisters project were essentially finished by then.

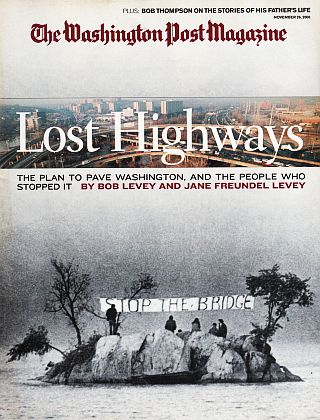

November 2000. Washington Post magazine featuring history of DC’s freeway battles & Three Sisters Bridge protests.

ECTC, meanwhile, in addition to being the prime mover citizen force to stave off the DC freeway carnage, also helped spawn three National Conferences on the Transportation Crisis, with citizens from 54 cities attending. These groups, in turn, helped push legislation that allowed States to turn over Federal highway funds for mass transit projects. As for Washington, DC proper, one summary of what the citizen and political opposition had accomplished there is offered by Washington Post reporters Bob and Jane Levy, who wrote in their retrospective November 2000 piece:

…Today, Washington has fewer miles of freeways within its borders than any other major city on the East Coast. More than 200,000 housing units were saved from destruction. So were more than 100 square miles of parkland around the metropolitan area. The city was spared from freeways bored under the Mall, freeways punched through stable middle-class black neighborhoods, freeways tunneled under K Street, freeways that would have obliterated the Georgetown waterfront and the Maryland bank of the Potomac.

The DC freeway fighters, however, had something of a magical coalition, populated by black and white activist citizen groups, but also various lawyers, power brokers and other influentials, plus media attention, all of which helped the community-based activists prevail in the freeway battle. Throughout the U.S., however, there were dozens of citizen uprisings over freeway projects that lacked such power, resulting in completed freeways through many of those communities. One freeway fight in Tennessee, however, resulted in a victory for saving parkland that affirmed such protections at the U.S. Supreme Court level.

Brooks Lamb’s “Overton Park: A People’s History,” Univ of Tennessee Press, includes the I-40 fight that went to U.S. Supreme Court. Click for copy.

Overton Park

Late in the 1960s and throughout the 1970s, a portion of the proposed route for Interstate Highway 1-40 threatened Overton Park, a popular 342-acre public park in Memphis, Tennessee. Founded in 1901, Overton Park includes a portion of an old-growth forest, and also a number of popular Memphis cultural and outdoor attractions, among them the Memphis zoo, the Memphis College of Art, an amphitheater, and the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, among other amenities. Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash performed there, while locals long enjoyed its playgrounds and jogging trails.

In the proposed routing of I-40, some 26 acres of the park were slated to be demolished to build freeway through the park to make it easier for suburban commuters to get to downtown. A small number of residents of midtown Memphis formed “Citizens to Preserve Overton Park,” and challenged the plan in court. Federal law by this time included specific provisions for protecting parkland and other areas, as indicated under section 4(f) of the Department of Transportation Act of 1966 and the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1968. Such lands could not be taken for a highway if other alternative routes were available. Ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the citizens favor in the landmark 1971 case, Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, upholding section 4(f) protections. However, that wasn’t the end of it. The City of Memphis and Tennessee Department of Transportation continued to propose a number of alternative Interstate 40 routes through Overton Park, including running the highway through a tunnel or in a deep trench. In 1978, Citizens to Preserve Overton Park successfully nominated the park to the National Register of Historic Places, thus guaranteeing that without approval from the U.S. Department of the Interior, Federal funding could not be used for projects that damaged the park’s historic integrity. The Memphis Commercial Appeal newspaper concluded the National Registration was the “final nail in the coffin” for efforts to route I-40 through Overton Park. Other Tennessee cities, however, were not as fortunate with their freeways, as noted earlier above, as another section of I-40 was built through a predominantly black section of Nashville, in central Tennessee.

Jason Henderson’s 2013 book offers some San Francisco freeway history, but also how the city might serve as an example of the sustainable transportation fight going forward. Click for copy.

The freeway battles of the 1950s-1970s period mark an important time in America when local citizen groups and various national activists confronted powerful highway interests – including the larger auto-industrial culture – and came away with some major victories and important changes in public policy. Their efforts helped make the transportation planning process more sensitive to social and environmental concerns. But that battle is far from over.

Today, freeways in America continue to draw public attention, whether in new proposals, upgrades and expansions, and new metropolitan beltway proposals. But there are also various efforts to dismantle and remove existing freeways and freeway stubs, especially in urban areas. And transportation activists across America continue to push for more mass transit and other alternatives, including better and more integration of bikeways and walkways into urban design and transportation plans. Yet the continuing rise in highway traffic and motor vehicle numbers inevitably means there will be more highway building ahead – and likely, more highway battles as well.

Readers of this story may also find the “Environmental History” topics page of interest, or General Motors-related stories, including: “G.M. & Ralph Nader,” “The DeLorean Saga,” and “Dinah Shore & Chevrolet.” Or visit the Home Page for additional story choices. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing and continued publication of this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 25 October 2020

Last Update: 6 December 2020

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Highway Wars – 1950s-1970s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, October 25, 2020.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“Highways,” Fortune, June 1938, Cover illustration by Hans Barschel (this edition also includes a story on Robert Moses).

Norman Bel Geddes, Magic Motorways, Random House, 1940. (Click for copy)

B. Alexandra Szerlip, The Man Who Designed the Future: Norman Bel Geddes and the Invention of Twentieth-Century America, Melville House, 2017.

“Highways Timeline,” GreatAchievements .org, National Academy of Sciences / National Academy of Engineering.

“Timeline: 1890-2010s,” Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Trans-portation.

Richard F. Weingroff, “Milestones for U.S. Highway Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration, 1892-1959,” DOT .gov.

“Interstate Highway System,” Wikipedia.org.

“The Evolution of the Interstate” Geotab.com (interactive map of year-by-year progress).

Lee Lacy, “Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Birth of the Interstate Highway System,” Army.mil, February 20, 2018.

John D. Morris, “Eisenhower Signs Road Bill; Weeks Allocates $1.1 Billion,” New York Times, June 1956.

“Interstate 10 in Texas,” Wikipedia.org.

Lewis Mumford, “The Highway and the City,” Architectural Record, April 1958.

Daniel P. Moynihan, “New Roads and Urban Chaos,” The Reporter, April 14, 1960.

Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Random House, 1961.

Lewis Mumford, The Highway and the City, Harcourt, Brace & World, 1963.

“Highwaymen Come to Morristown,” Satur-day Evening Post, April 9, 1966,

“War Over Urban Expressways,” Business Week, March 11, 1967.

“Hard-Nosed Highwaymen Ride Again,” Life, April 14, 1967.

“U.S. Road Plans Periled by Rising Urban Hostility,” New York Times, November 1967.

“Rising Furor Over Super Highways,” U.S. News & World Report, November 27,1967.

“Freeway Versus the City,” Architectural Forum, January 1968.

“Fighting the Freeway,” Newsweek, March 25, 1968,

Lyn Shepard, “Freeway Revolt, Christian Science Monitor, (ten-part series of newspaper stories on urban freeways in U.S. cities), June & July 1968.

“Let’s Put The Brakes on the Highway Lobby!,” Readers Digest, 1969.

Ruth Wolf, “Block That Freeway,” Seattle Magazine, February 1969.

Alfred C. Aman, Indiana University Maurer School of Law, “Urban Highways: The Problems of Route Location and a Proposed Solution,” 1970.

Helen Leavitt, Superhighway–Superhoax, Doubleday, January 1970.

“Highway Revolts in The United States,” Wikipedia.org.

Nicholas LePan, “Visualizing the Footprint of Highways in American Cities” [before-and-after maps of 6 American cities impacted by urban highways], VisualCapitalist.com, April 4, 2020.

Ben Kelley, The Pavers and The Paved: The Real Cost of America’s Highway Program, D.W.Brown, 1971.

John Robinson, Highways and Our Environ-ment, McGraw-Hill, 1971.

Ronald A. Buel, Dead End: The Automobile in Mass Transportation, Prentice-Hall, 1972.

Emma Rothschild, Paradise Lost: The Decline of the Auto-Industrial Age, Random House, 1973.

Marshall Goodwin, Jr., “Right-of-Way Controversies in Recent California Highway-Freeway Construction,” Southern California Quarterly, April 1974.

Jan Schaeffer, “Trust Fund Renewal to Slip By,” Environmental Action, October 17, 1970.

“Highway Battle Pits People Against Power,” Environmental Action, October 17, 1970.

“Washington: Freeway Blackmail,” Environ-mental Action, October 17, 1970.

“Ending the Map Gap…,” Environmental Action (advertisement calling for completion of Interstate Highway segments in urban areas), October 17, 1970.

Linda Katz, “In The 1970s, ‘Trust-Busting’ Means Halting Highways,” Environmental Action, May 29, 1971.

“Highway Action Coalition,” Wikipedia.org.

Dennis Hayes, “Can We Bust the Highway Trust?,” Saturday Review, June 5, 1971.

David E. Rosenbaum, “For the Highway Lobby, a Rocky Road Ahead,” New York Times, April 2, 1972.

Peter Harnik, “Highways and The House: Keep on Truckin’,” Environmental Action, October 14, 1972.

Richard F. Weingroff, “Busting the Trust: Unraveling the Highway Trust Fund, 1968-1978,” Federal Highway Administration, FHWA.DOT.gov, June 2013.

Tom Wicker, “In The Nation: Busting the Highway Trust,” New York Times, December 5, 1972.

“Old Highways Never Die,” Environmental Action, December 6, 1975.

James Howard Kunstler, The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America’s Man-Made Landscape, Simon & Schuster, 1993.

Mark Soloff, “History of Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs),” NJtpa.org, January 1998.

James J. Casey, Jr., The Politics of Congestion: The Continuing Legacy of the Milwaukee Freeway Revolt, Northwestern University, January 2000.

“Freeway Removal,” Wikipedia.org.

Joseph F.C. DiMento and Cliff Ellis, Changing Lanes: Visions and Histories of Urban Freeways, MIT Press, 2012.

San Francisco

“Four Freeways Added to 1945 Master Plan,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 18, 1951.

Charles Thieriot, “Where to Build SF Freeways?” San Francisco Chronicle, June 24, 1956.

“Board Kills Plans for 6 SF Freeways,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 27, 1959.

“Freeway Revolt No Passing Thing,” San Francisco Examiner, February 2, 1959.

“Freeway Fighters,” New York Times, April 29, 1962.

“Anti-Freeway Rally in Panhandle,” San Francisco Chronicle, April 4, 1964

“Both Freeway Plans Rejected,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 22, 1966.

Dinyar Patel, “Saving America’s ‘Last Lovely City’: The San Francisco Freeway Revolt,” SURJ/ Stanford.edu, Spring 2004.

“California State Route 480″ [Embarcadero], Wikipedia.org.

Katherine M. Johnson, “Captain Blake Versus the Highwaymen: Or, How San Francisco Won the Freeway Revolt,” Journal of Planning History, October 30, 2008.

Chris Carlsson, “The Freeway Revolt: Historical Essay,” FoundSF.org (San Francisco digital archive).

William Issel, “Land Values, Human Values, and the Preservation of the City’s Treasured Appearance: Environmentalism, Politics, and the San Francisco Freeway Revolt,” Pacific Historical Review, November1, 1999.

Katrina Schwartz, “What Would San Francisco Have Looked Like Without the ‘Freeway Revolt’?,” em>KQED.org, August 2, 2013.

“The History of San Francisco Bay Area Freeway Development (Part 1—The City of San Francisco),” California Highways, CaHighways.org.

“San Francisco Freeway Revolt” [w/map by Steve Boland], CalUrbanist.com, 2005.

Gary Kamiya, “A Freeway Through the Sunset District? Roots of a San Francisco Revolt,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 20, 2019.

Gary Kamiya, “Powerful Forces Wanted Freeways All Over SF. Here’s How They Were Stopped,” SFchronicle.com, October 4, 2019.

Griffin Estes, “The Panhandle Freeway And The Revolt That Saved The Park,” HoodLine.com, March 29, 2015.

The Congress for the New Urbanism, “A Freeway-Free San Francisco,” CNU.org.

Justin Matthew Germain, “Housewives Save the City From The ‘Cement Octopus’! Women’s Activism in the San Francisco Freeway Revolts, 1955 -1967,” A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Bachelor of Arts Requirements in History, University of California, Berkeley, December 2, 2016.

Boston

“Interstate 695 (Massachusetts),” Wikipedia .org [Re: Inner Belt].

Cambridge Historical Society, “The Inner Belt,” CambridgeHistory.org [w/timeline].

Alan Lupo, Frank Colcord & Edmund P. Fowler, Rites of Way; the Politics of Transportation in Boston and the U.S. City, Little, Brown, 1971,

Max Reyes, “50 Years after Inner Belt Protest, Activists Gather Again,” Boston Globe, January 25, 2019.

New York City

Pierre Christin (Author), Olivier Balez (illustrator), Robert Moses: The Master Builder of New York City, Nobrow, December 2014.

Michael Caratzas, “Past Meets Futurism Along the Cross-Bronx: Preserving a Significant Urban Expressway,” Journal of Historic Preservation, Spring 2004, pp. 25-35.

Kyle Barr, “‘The Land of Moses: Robert Moses and Modern Long Island’ Opens at The Long Island Museum,” tbrNewsMedia.com, July 10, 2018.

Linda Poon, “Mapping the Effects of the Great 1960s ‘Freeway Revolts’: Urbanites Who Battled the Construction of the Interstate Highway System in the 1960s Saved Some Neighborhoods — But Many Highways Did Transform Cities,” Bloomberg.com, July 23, 2019.

Highways & Race

B. Drummond Ayres, Jr., “’White Roads Through Black Bedrooms’,” New York Times, December 31, 1967.

Raymond A. Mohl, Department of History, University of Alabama at Birmingham, “The Interstates and the Cities: Highways, Housing, and the Freeway Revolt,” PRRAC.org (Poverty & Race Research Action Council), 2002.

Raymond A. Mohl, University of Alabama at Birmingham, “Stop the Road: Freeway Revolts in American Cities,” Journal of Urban History, July 2004.

Raymond A. Mohl, “The Interstates and the Cities: The U.S. Department of Transportation and the Freeway Revolt, 1966–1973,” The Journal of Policy History (The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA), Vol. 20, No. 2, 2008.

Raymond A. Mohl, “Citizen Activism and Freeway Revolts in Memphis and Nashville: The Road to Litigation,” Journal of Urban History, May 2014.

Eric Avila, The Folklore of the Freeway: Race and Revolt in the Modernist City, Quadrant paperback, 2014.

Eric Jaffe, “The Forgotten History of L.A.’s Failed Freeway Revolt: The Story of Boyle Heights Reminds Us That Urban Highway Teardowns Don’t Always End in Victory,” Bloomberg.com, July 23, 2014.

Dan Albert, “The Highway and the City and The Making of Modern America,” TheTowner .com, October 21, 2016.

Tom Lewis, Divided Highways: Building the Interstate Highways, Transforming Ameri-can Life, Viking, 1997.

Olivia Paschal, “The Bitter History Behind the Highways Occupied by Protesters,” Facing South.org, June 5, 2020.

Nithin Vejendla, Opinion, “Freeways are Detroit’s Most Enduring Monuments to Racism. Let’s Excise Them,” Detroit Free Press, July 20, 2020.

Kevin M. Kruse, “What Does A Traffic Jam in Atlanta Have To Do With Segregation? Quite A Lot,” New York Times Magazine, August 14, 2019.

Alana Semuels, “The Role of Highways in American Poverty; They Seemed Like Such a Good Idea in the 1950s,” TheAtlantic.com, March 18, 2016.

David Karas, University of Delaware, “Highway to Inequity: The Disparate Impact of the Interstate Highway System on Poor and Minority Communities in American Cities,” New Visions for Public Affairs, Vol. 7, April 2015.

William Fox, “Segregation Along Highway Lines: How the Kensington Expressway Reshaped Buffalo, New York,” A Thesis Submitted for the History Department & Honor’s College, The State University of New York at Buffalo, May 2017.

Problogic, “Interstate Injustice: Plowing Highways Through Minority Neighborhoods,” Panethos. WordPress.com, Updated, April 7, 2018.

Washington, D.C.

“Inner Loop (Washington, D.C.),” Wikipedia .org.

“North Central Freeway (Washington, D.C.),” Wikipedia.org.

Richard F. Weingroff, “The D.C. Freeway Revolt and the Coming of Metro,” Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, FHWA.DOT.gov.

“Sammie Abbott,” Wikipedia.org.

Craig G. Simpson, “The D.C. Black Liberation Movement Seen Through the Life of Reginald H. Booker,” WashingtonAreaSpark.com, Jan-uary 28, 2020.

Willard Clopton, “Controversial Road Projects To Be Delayed: NCTA Plan Studied. NCTA Tactics Protested; Key District Road Jobs Are Delayed,” Washington Post, January 19, 1963, p. C-1.

Willard Clopton, “Rail Transit Plan Sent To Congress: President Asks Prompt, Favorable Action on Project,” Washington Post, May 28, 1963, p. A-1.

Peter Milius, “Freeway Foes Carry Protest to District Building,” Washington Post, January 18, 1967, p. C-1.

“Case of Three Sisters,” St. Louis Post-Dis-patch, January 5, 1968.

“Statement of Sammie A. Abbott, Publicity Director, Emergency Committee on the Transportation Crisis,” Hearings before the Subcommittee on Roads of the Committee on Public Works, U.S. House of Representatives, April 2-4, 1968.

Jack Eisen, “D.C. Freeway Foes Grow More Disruptive, Washington Post, November 9, 1968, p. B-1.

Jack Eisen and Irna Moore, “Bridge Vote Tied To Metro Funds: Metro Fate Tied to Bridge,” Washington Post, July 23, 1969.

Jack Eisen and Ina Moore, “Fists Fly at Voting on Roads: Bridge Foes Erupt as City Bows to Hill,” Washington Post, August 10, 1969, p. 1.

B. D. Colen, “Nearly 100 Bridge Foes ‘Occupy’ Three Sisters Islands: Students Lead Protesters Awaiting Start of Construction Today,” Washington Post, October 13, 1969, p. D-1.

Martio Weil, “Bridge Work Starts: Protestors Cause Brief Delay on 3 Sisters,” Washington Post, October 14, 1969, p. C-1.

Ivan C. Brandon, “141 Protestors Arrested at Three Sisters Site,” Washington Post, October 16, 1969, p. B-1.

“Ban the Bridge?,” Newsweek, November 3, 1969.

“Washington: Freeway Blackmail,” Environ-mental Action, October 17, 1970.

Angela Rooney, “Freeways: Urban Invaders,” The Environmental Journal, October 1971.

Jack Eisen, “House Releases District Subway Funds: Leadership Rebuffed, 195 to 174,” Washington Post, December 3, 1971, p. 1.

Rice Odell, “To Stop Highways Some Neighbors Take to The Streets,” Smithsonian Magazine, March 1972.

Jack Eisen, “Md. Vetoes I-95 Extension Into District,” Washington Post, July 13, 1973.