In late October 2019, the mayor of Pittsburgh, PA, Democrat Bill Peduto, shook up the nation’s energy and petrochemical establishment, and sent local Chamber of Commerce types into a bit of frenzy, when he made some controversial remarks about the kind of industrial development taking place in Western Pennsylvania. Peduto, a leader among city mayors on green energy, spoke out against a future of fracking-fueled petrochemical and plastics industrialization, the outlines of which were already apparent on the landscape north of Pittsburgh where a $6 billion plastic-producing ethane cracker complex, owned by Shell Oil, was then under construction (photo below).

Construction cranes dominate the scene in Beaver County, PA where Shell Oil is building a $6 billion ethane cracker complex to make plastic pellets. Plant will be fed by fracking wells and pipeline networks throughout the region.

Peduto, in fact, was quite blunt about his position: “Let me be the first politician to say publicly, I oppose any additional petrochemical companies coming to Western Pennsylvania. …We don’t have to become the petrochemical/plastics center of the United States.” Peduto wasn’t out to stop the Shell cracker plant shown above. No, he acknowledged the plant was out of his jurisdiction and it would be foolish to take that stand since the project was nearing completion, slated to open in 2021. But Peduto was concerned about what might be coming next, as ExxonMobil was then looking around the region for a second possible cracker site, and some rumors had cited a third for the area.

October 31, 2019. Pittsburgh mayor, Bill Peduto, making his remarks at the Climate Change Summit.

(About a week after the controversy had formed, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette veteran reporter, Don Hopey, did a piece on the various parties reacting to Peduto’s remarks. See, “To Crack or Not To Crack: Peduto Fires Salvo in Regional Climate Change Battle.”).

Yet Peduto’s speech was both courageous politically and raised legitimate and important concerns, not only for the Pittsburgh region, but for the future of the nation and planet.

Peduto has worked to make Pittsburgh a leader in high-tech, green energy development and environmental cleanup. Fracking and plastics, meanwhile, are at the center of the fossil-fuels model that will only feed climate change and worsen the plastics mess.

“I ask you,” said Peduto at one point, “how can we get our community to work together as one, to be able to end the nonsense of debating whether or not climate change is real and whether man is responsible; to end the nonsense of being able to say that our economy of the future is based on fracking and petrochemicals…?”

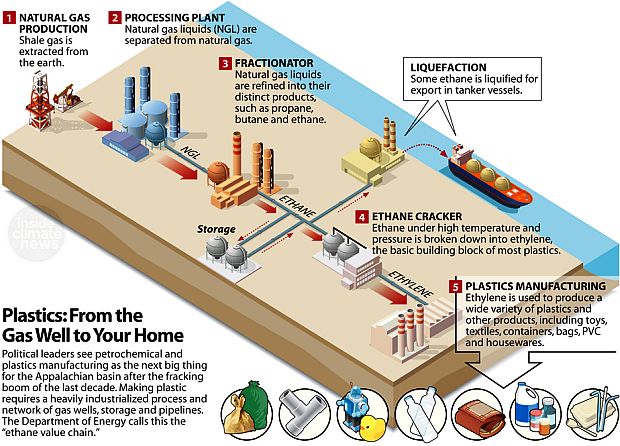

Just north of Pittsburgh, in Beaver County, where Shell’s ethane cracker is being built, the fossil fuels model is taking form big time, as a network of wells, pipelines, and processing facilities has begun to unfold in what might be called a “plastics industrialization.” Shell’s cracker will be supplied by fracking wells – i.e., wells that use high-pressure hydraulic fracturing of underground geology to extract oil and gas – drawing from the gigantic Marcellus-Utica Shale deposit that underlies more than 60 counties in the tri-state Pennsylvania/West Virginia/Ohio region (some studies rank that deposit as the world’s second largest natural gas field). The Shell plant will crack ethane molecules from incoming natural gas liquids to make polyethylene pellets – raw plastic – which is then shipped to manufacturers to create an array of plastic products.

Graphic shows tri-state PA-OH-WV region with underlying Marcellus-Utica shale formations and locations of three ethane crackers. Sources: U.S. Energy Information Agency and Paul Horn / Inside Climate News.

But the Shell plant is only the opening salvo. Some say the region can support up to five or more ethane crackers, given the Marcellus-Utica bounty. In addition to the reports of ExxonMobil’s scouting in the Pittsburgh region, and rumors of others, two additional cracker units have been planned nearby in Ohio and West Virginia, as seen on the above map. And each cracker complex brings a corollary network of supply wells, pipelines, fractionaters, etc.

Royal Dutch Shell artist’s rendition of completed ethane cracker petrochemical processing complex now being built in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, northwest of Pittsburgh, PA.

Mayor Peduto, meanwhile, is not happy with what he sees coming, fearing his “clean industry” build for Pittsburgh and the region’s future may be in jeopardy. “When you go and you talk to Duolingo [software] and Google and Microsoft and Facebook and Argo AI and Uber, the companies that are employing thousands [in Pittsburgh]— companies like Philips bringing 1,100 jobs into the city, and SAP 700 — have they said they want to live in a city with seven petrochemical plants around it?”Should we as a nation be building more industrial infrastructure that simply embeds the petrochemical -plastics-fossil-fuels model deeper into the national economy? The Pittsburgh region, which in recent decades has just climbed out of the “dirty skies coal-and-steel era,” may well be heading for a new era of petrochemical peril while stoking the greenhouse.

In taking his stand on petrochemicals regionally, Peduto is also bringing the issue to the top of the national agenda: Should we as a nation be building more industrial infrastructure that simply embeds the petrochemical-plastics-fossil-fuels model deeper into the national economy? Should we be building $6 billion chemical plants, in essence, to make more environmentally-problematic plastic while adding to the planet’s CO-2 load? Is that really an economically sound and environmentally smart investment strategy for the future? These cracker-complexes, and their supporting infrastructure, are not temporary investments that can be easily undone. Rather, they are huge 25-to-30 year commitments of sunk capital goods that then “have to be used” once they are built – a reality the fossil fuels industry is counting on.

This generalized graphic from “Inside Climate News” and U.S. Department of Energy, shows the natural gas-to-plastics process and all the various capital goods required in that kind of fossil-fuel-based industrialization.

True, the plastic-petrochemicals-fossil fuels model has been among the world’s most important economic and wealth-producing engines, providing jobs, innovation, and array of useful products. Yet much of the petrochemical success story has come with a high price tag and is fraught with “genie-out-of-the bottle” consequences.Too many “wonder chemi-cals”–plastics among them –were released without full toxicological profiles, little regulation, and no end plan. Too many “wonder chemicals” – plastics among them – were released without full toxicological profiles, little regulation, and no end plan, resulting in toxic pollution, worker cancers, and public health risks and exposures that continue to this day.

The polyethylene output of the Shell complex in Beaver County, and others like it, will add to the plastic peril the world is already facing – from Texas-size swirls of plastic junk now circulating in the Pacific Ocean (and in micro form, now infiltrating food chains), to the mountains of discarded plastic heading to landfills, incinerators, and export to who knows where. Added to this, of course, is the petrochemical component of climate change. The Shell cracker will release some 2.25 million tons of greenhouse-stoking carbon dioxide annually, equivalent to the yearly output of about 430,000 automobiles. In the region’s well fields, meanwhile, methane emissions will be considerable, as the 1,000-to-1,300 fracking wells needed to supply the cracker are notorious methane emitters, as are typically leaky gathering lines that collect gas from those wells (The FracTracker Alliance has cited a Nature Conservancy study calculating that each 19-acre well pad requires, on average, about 3.1 miles of gathering lines). Methane, though shorter-lived in the atmosphere than CO-2, is a more potent global warming gas. Then there are the “garden variety” operational impacts — emissions, plant fires, pipeline leaks, etc. More of this kind of industrialization is surely perilous, as numerous scientists, academics, and environmental leaders have projected.

Bad Air

When it comes on line, the Shell cracker north of Pittsburgh will become the leading polluter in Western Pennsylvania and the third largest in the state. While local citizens and environmental groups have been successful in securing fence-line monitoring at the Shell site for detecting leaks and excess pollution, the permitted pollution load coming from the plant, and affiliated supply, manufacturing and transportation activities, will impose a burden on the Pittsburgh region, effectively undoing clean air progress made since the late 1990s. Pittsburgh in recent years has not reached clean air goals, but has been moving in the right direction. Air quality throughout the seven–county metro area has not met the annual federal limits for ground-level ozone, a pollutant that raises asthma and lung risks for children, and is also problematic for the elderly, and generally at higher levels.

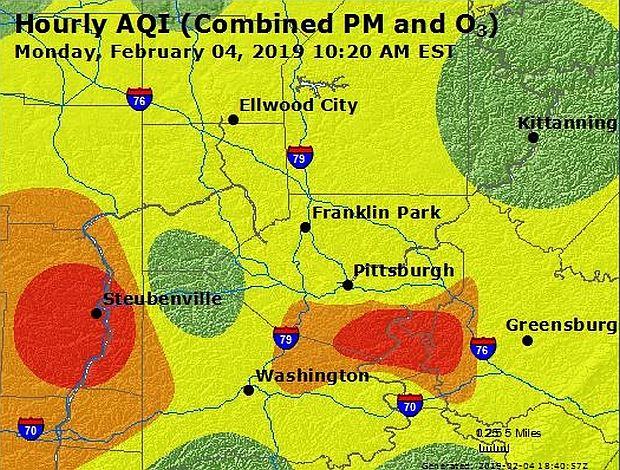

Map sample shows hourly air quality index (AQI ) in the Pittsburgh-Eastern Ohio area on February 4, 2019 at 10:20 a.m for a combined reading of particulate matter (pm 2.5) and ground-level ozone (O-3). Green is good, yellow moderate, orange unhealthy for sensitive groups, and red unhealthy generally. On this particular day there was an atmospheric inversion, which tends to have a “lid” or trapping effect on regional pollution.

“If you are using ethane to drive a petrochemical industry,” explained James Fabisiak, University of Pittsburgh toxicologist in a 2017 Pittsburgh Quarterly interview, “that creates a new pathway for volatile organic compounds and hazardous air pollutants being released. We know volatile organic compounds can contribute to ozone formation. This industry brings an unprecedented amount of volatile organic compounds to the area.” Among the Shell cracker’s permitted pollutant levels will be some 484 tons annually of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), like ground-level ozone. More than 30 tons of hazardous air pollutants will be released by the cracker each year – including benzene and toluene, which have been linked to various cancers and/or other health impacts on the brain, liver, and kidney, as well as birth defects. Also permitted will be 159 tons annually of particulate air pollution – called “particulate matter 2.5,” or PM 2.5, referring to the tiny size of particles that pass through the lung and into the bloodstream where they can contribute to cardiovascular and respiratory disease, as well as lung and bladder cancer. In addition, treated wastewater released to the Ohio River from the Shell cracker will contain some quantities of potentially hazardous chemicals and known human carcinogens such as benzene, benzo[a]pyrene, and vinyl chloride.

Pipelines

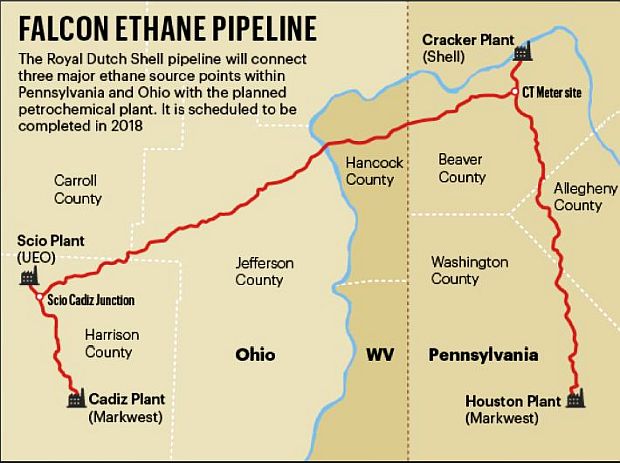

Part of the related infrastructure that comes with the fracking-plastics model of industrialization are pipelines – not just one or two, but over time, a welter of such lines, extensions, and upgrades, not only to supply ethane crackers, but also to move fracked gas out of the region for export. Among lines now being built for the Shell cracker is the company’s Falcon Pipeline project – a two-leg, 97-mile system that will carry ethane from fracking field wells and processing units in Ohio and southwestern Pennsylvania to the cracker in Beaver County.

Shell’s Falcon Pipeline will collect raw natural gas feedstock from fracking-well supplied processing points, and then to the Shell ethane cracker in Beaver County, northwest of Pittsburgh.

Along the two legs, Shell has had to negotiate its right-of-ways with local property owners and has agreements with about 300 landowners. As with most modern pipelines, the Shell lines will be monitored by computer for operation and safety, and control valves installed at various intervals can shut off the lines remotely should problems arise. Still, accidents happen, and Shell for one has had its share of incidents nationwide and around the world. (See for example, “Shell Plant Explodes, Belpre, OH, 1994″). And beyond the Falcon lines, there are a number of other pipelines already operating in the region, others under construction, and still others being planned for moving shale-derived liquids and gases (for an overview of Pennsylvania pipelines, and an interactive map, see “Pennsylvania Pipelines and Pollution Events” by the FrackTracker Alliance).

Pipeline leaks, explosions and fires have occurred in the region, some quite recently. In February 2015, an ethane pipeline in Brooke County, WV operated by Appalachia-Texas Express (ATEX) ruptured and exploded, burning more than 23,000 barrels of ethane, with flames sent hundreds of feet into the air and burning five acres of land. Closer to Pittsburgh, in September 2018, the natural gas Revolution Pipeline in Beaver County – built as part of Energy Transfer’s (Sunoco Logistics) 100-mile Revolution Pipeline system to gather dry and wet gas from local wells and deliver it to a separating plant in Washington County, PA – leaked and exploded. That incident occurred around 5 a.m., turning night into day, as flames shot 150 feet into the air. The blast and fire destroyed one house, a barn, two garages, several vehicles, and some high tension electric lines. The incident forced the temporary evacuation of nearly 50 residents from 30 homes, shut down a section of a highway, and left 1,500 people without electric power due to the toppled transmission lines.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette photo of charred acreage following the September 2018 explosion and fire from the Revolution Pipeline in Center Township, Beaver County, Pennsylvania. Darrell Sapp/Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Closer in shot of damage following Revolution Pipeline explosion and fire of September 2018 in Center Township, Beaver County, PA. Darrell Sapp/Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Pipeline incidents are not rare occurrences. According to data from the U.S. Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, between 2010 and 2018, over 280 pipeline incidents were reported in Ohio, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania. Some 70 of those incidents were fires and/or explosions. Of 108 pipeline incidents occurring in Pennsylvania between January 2010 and mid-July 2018, there were 8 fatalities, 15 injuries, more than $66 million in property damage, and some 1,100 people forced to evacuate their homes.

Well Explosions

Pipelines aren’t the only volatile part of the fossil fuels/plastics industrialization model. Fracking wells, for one, have also had their explosive and leaky moments. In February 2014, a Chevron-owned shale well about 70 miles south of Pittsburgh in Green County, PA exploded, killing one worker and burning for several days before being contained. The explosion happened as workers were preparing the Lanco 7H well for production. But the force of the explosion from that well also ignited another well, the Lanco 6H, on the same well pad. In a March 2014 notice of violation letter from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), Chevron was cited for “hazardous venting of gas,” “open burning,” and “discharge of production fluids onto the ground.” But according to DEP, Chevron’s most serious violation was an equipment failure at the wellhead believed to have caused the explosion that took the life of 27-year-old worker at the site. DEP later fined Chevron $940,000 for the explosion, noting: “The penalty points to Chevron’s failure to construct and operate the well site to ensure that health, safety and environment were protected…” The company also paid a $5 million settlement in a wrongful death lawsuit for the worker who was killed in the incident.

February 2014 fire at a Chevron-owned shale gas well operation in Greene County, PA, following explosion, 70 miles south of Pittsburgh. Photo, KDKA-CBS TV News.

In February 2019, another major shale gas well explosion and fire occurred about 80 miles southwest of Pittsburgh in the Ohio Valley at Powhatan Point, Ohio. This well – operated by XTO Energy, a subsidiary of ExxonMobil – burned and leaked gas for several weeks before it was contained. Following the initial blowout residents from some 30 homes within one mile of the well were evacuated and kept away for a few days before returning. An unknown quantity of brine and produced water from the site was also released into streams that flow into the Ohio River during this event, estimated by EPA to be more than 5,000 gallons. But a major discovery at this well event was its gigantic hemorrhage of methane emissions. In fact, satellite monitoring of this one well explosion found that in the 20 days it took to stop the uncontrolled release of natural gas, about 20 tons of methane was released per hour.Methane emissions from the XTO Energy (Exxon Mobil) well blow-out over 20 days were estimated to be about 60,000 tons. That’s more methane than European countries like France, Spain and Norway release in one year. Assuming that to be an average release rate for the 20-day period, methane emissions from that one well blow-out would total about 60,000 tons. That’s more methane than entire European countries like France, Spain and Norway release in one year.

Granted, this was an exceptional event. Still, thousands of fracking wells now operating in the Western Pennsylvania/Ohio Valley region routinely release methane to the atmosphere. Recent studies on the rise of fracking generally in the last decade have found a corresponding spike in atmospheric methane emissions solely attributed to fracking – wells which routinely release 2-to-6 percent of the gas they produce.

In addition to well fires and explosions, intermediate gas processing plants – those used for storage and chemical separation in the fracking-to-cracker process – also have leaks, fires and explosions. In mid-December 2018, a fire at the MarkWest (Marathon Petroleum) Houston, PA processing plant in Washington County, southwest of Pittsburgh, occurred there after a condensate tank exploded, burning four workers. The MarkWest facility, and other Ohio and Pennsylvania gas processing operations owned by MPLX/Marathon, have also been cited for alleged violations in recent years for failure to monitor and report leaks of gas and underreporting of gas leak rates, as well as VOC emissions at truck loading and gas compressor stations in Pennsylvania and Ohio.

Exploiting the Region

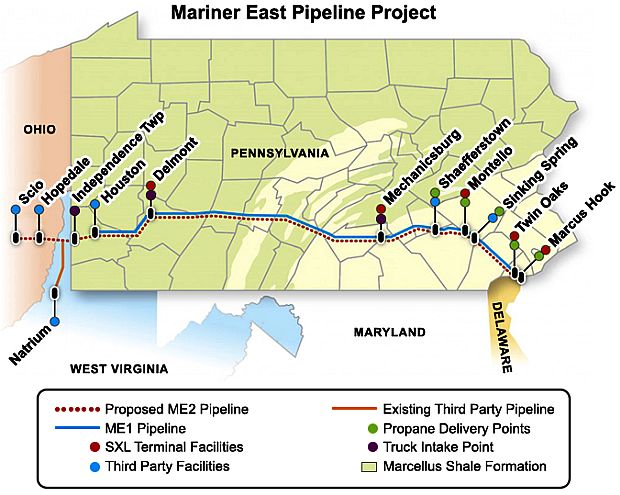

Meanwhile, looking at the larger regional context across Pennsylvania and beyond, additional infrastructure for the increased exploitation of the Utica-Marcellus shale resource base has already arrived. Pipeline systems in the tri-state OH-PA-WV shale region point up the push for continued fracking-style industrialization – including that for overseas export from the east coast. Take, for example, the Mariner East pipelines – a series of three west-to-east lines for moving natural gas liquids from the fracking fields across Pennsylvania. The lines are owned by Energy Transfer/Sunoco Logistics and run roughly along a 350-mile route across some 17 counties in southern Pennsylvania (see map below). The Mariner East pipelines extend from the Utica-Marcellus Shale region in Western Pennsylvania and Eastern Ohio, to a former Sun Oil refinery location at the extreme eastern end of the state at Marcus Hook, PA, on the Delaware River.

Map of route that 3 Mariner East pipelines follow from the Utica-Marcellus shale fracking fields in Western PA-Eastern Ohio-West Virginia, transporting natural gas liquids to Marcus Hook, PA for processing & export.

The primary purpose of these lines is to transport the Utica-Marcellus natural gas liquids (ethane, butane, pentane, and propane) to Marcus Hook for storage, processing, and overseas export for plastics production. The three lines run generally in the same corridor: Mariner East 1 is an old east-to-west gasoline line from the 1930s updated in 2015 to handle west-to-east natural gas liquids (NGLs); Mariner East 2, a second new line begun in February 2017 at a projected cost of $2.5 billion, also to carry NGLs; and the Mariner East 2X, a third NGLs line begun in 2018. These pipelines represent the largest investment of private money in Pennsylvania history, something in the neighborhood of $3 billion. The three lines, when fully operational, will have an estimated shipping capacity of more than 700,000 barrels of NGLs per day. However, the Mariner lines have been controversial in their various updates and expansions, meeting citizen resistance, at least one lawsuit, and collecting dozens of PA Department of Environmental Protection fines and enforcement actions for construction damages and pollution. Still, the three lines – built by Sunoco Logistics and partners – are further evidence of the enormous capital infrastructure expansion growing out of the Utica-Marcellus shale region. And beyond the Mariner lines themselves, at the Marcus Hook end of the lines, more fossil-NGL infrastructure is being added there to accommodate overseas exports, East coast markets, and possible on-site manufacturing.

Marcus Hook, PA, where a World War II Sun Oil Co. refinery once stood, a new “natural gas liquids/energy” hub is emerging, fed by pipelines supplying Marcellus-Utica fracked natural gas liquids from Western PA and Eastern OH, for export to European petrochem companies, possible on-site manufacturing, and regional customers.

Marcus Hook is being hyped to become an energy/NGLs hub to rival those on the Gulf Coast, with the old refinery complex receiving a $200 million update. Most of the NGLs that is now delivered to Marcus Hook is loaded on ships bound for European petrochemical manufacturers. Energy Transfer/Sunoco Logisitics is also exploring opportunities to build manufacturing facilities at Marcus Hook that would use the gas liquids as a raw material. The former Sun Oil refinery at this location was idled in 2011 and was acquired in 2012 by Sunoco Logistics, then eyeing its value anew in the shale gas era. By 2017, Sunoco Logistics merged with Energy Transfer Partners and the site is currently owned by Energy Transfer subsidiary, Sunoco Partners Marketing and Terminals. There is also a huge existing underground cavern on the Sun Oil grounds that can be used for natural gas storage. Storage caverns for NGLs are also being sought in the Pittsburgh area.

Gov't Cheerleading? 2018 'Report to Congress' from U.S. Dept. of Energy on future of fracking-fueled ethane infrastructure in the U.S. and the Marcellus-Utica Appalachian region.

Infrastructure Race

Today, there is a big-time industrial building race underway – an investment and capital goods race between a green economy infrastructure vs. a dirty economy infrastructure.

Solar, wind, IT, and energy efficiency technologies are in the former category. Old fossil fuel interests persist in the latter category with polluting technologies and manufacturing facilities now powered by the oil and natural gas fracking boom.

Fossil-fuel giants like Shell and ExxonMobil are moving quickly to build their “old economy” shale-to-cracker capital goods plants and networks – wells, pipelines, storage facilities, waste pits, etc. (much with generous taxpayer subsidies). Once these extensive networks are established they become “sunk investments”; capital goods that industry will argue “must be used” for the next 20-to-30 years. In the process, such region-wide fossil-powered infrastructure will be so large and capital-usurping that it will surely dissuade – if not eclipse and prevent – green economy investments from occurring in those same regions.

Bill Peduto said much the same thing in his October 2019 remarks at the Climate Change Summit, stating that investment in fossil fuels was coming at the expense of what he saw as trillions of dollars that could be invested in sustainable technologies. “There is a direct opportunity cost when we continue to invest in 19th century industry [ i.e., fossil-fuel styled development] that costs us the opportunity to bring 21st century industry to this region.”

Pushed Around

“…The people that live here are in the way. We’re in a gas field. They [indus-try] want every square inch of this land… We’re just in the way – for plastic…” -Steve WhiteIn the Pittsburgh region, meanwhile, losses and impacts from the Shell cracker complex now under construction are already visible. Since about 2011, Steve White, a pilot and contractor who lives with his family in Beaver County, has watched the spread of cracker-related growth in the region from the vantage point of his Csena airplane at 30,000 feet. White told Climate Change News in a February 2019 video interview how the early growth of gas wells, pipelines, processing plants, and waste pits has taken form across the Pittsburgh region. As he saw it then, it was slicing up farms; encroaching on homes, schools, and businesses.

“We are just in the way,” White said. “…The people that live here are in the way. We’re in a gas field. They [industry] want every square inch of this land… They’re not locating these sites to accommodate the residents that live here. They’re doing it strategically to get as much gas out of the land as they can. So we’re just in the way – for plastic…”

Too often in America, corporations and government agencies view the American landscape as their private chess board, where they can move their exploitive industrial pieces about at will, regardless of consequence. For average folks bullied in this process, and without the financial means of appeal, there is no fair play and no real accountability. For too long, the waves of industrialization have repeatedly ravaged communities and the environment. In western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Valley, the long history of natural resources plunder has been played out time and time again – from timber clear cuts and the early oil boom, followed by rapacious strip mining to subterranean long-walling. Repeated assaults, sometimes over the same land and in the same communities. Now comes fracking and plastics industrialization. It’s just more of the same.

The Alternative

But there is another way forward. Alternative economic investments in green energy industries and green manufacturing that move away from the fossil-fuel based petrochemical model need to move to the front of the line in Pittsburgh and all regions.

This kind of investment and industrial development is currently occurring throughout the U.S. and around the world, and is a viable, cleaner, and better alternative to what is currently occurring, generating jobs, new service and support businesses, and other local and regional economic activity.

Numerous reports, studies, and books on the success of such investments, and their projections for the near future, attest to the rising potential and viability of the green energy/green manufacturing model (click on book images for Amazon .com descriptions).

Renewable energy, in fact, is the fastest-growing energy source in the United States, increasing 67 percent from 2000 to 2016. Renewables made up nearly 15 percent of net U.S. electricity generation in 2016, with the bulk coming from hydropower (6.5 percent) and wind power (5.6 percent).

Solar generation is projected to climb from 7 percent of total U.S. renewable generation in 2015 to about 36 percent by 2050, making it the fastest-growing electricity source. Over 242,000 Americans work in solar – more than double the number in 2012 – at more than 10,000 companies in every state. In 2018, the solar industry generated a $17 billion investment in the American economy.

As of July 2018, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency listed 82 Fortune 500 companies on its Green Power Partners program – companies using green power sources to generate some or all of their electricity supply, representing a total, at that time, of nearly 24 billion kilowatt-hours of green power annually.

Some of the listed companies – including Apple, Microsoft, Intel, Cisco Systems, Starbucks, BD Health Care, Capital One, Goldman Sachs, BNY Mellon, Met Life, Netflix, Biogen, and others – are using 100 percent or more (generating a surplus) of their electric power from renewable sources. And some are also using their own on-site and/or fully-owned renewable sources.

In the years ahead, there will continue to be economic opportunities for investment in renewable energy technologies and green manufacturing. Locations with university research talent and programs, such as Pittsburgh, are ideally suited for developing and expanding renewable energy R&D programs, helping to advance those technologies and attracting new green manufacturing to their regions that will spawn new jobs and healthy and safe local economies.

So today, there is a choice in how regions invest and build their economies – and political and corporate leaders need to be leading the green challenge. Bill Peduto, for one, is doing that, and is sounding the alarm for his own region and others, stating that the old fossil-fuels-petrochem model of investment and industrialization – once all the costs are truly considered – is no longer the smartest, safest, or cleanest kind of economic development.

Plastics production, meanwhile, needs to face up to its carbon and environmental costs if it is to survive in the future. Granted, plastics have contributed to improved automotive fuel economy, critical parts in wind and solar systems, communications, medicine, and other fields. But can a future plastics industry shed its carbon costs, its toxic emissions, and its open-ended waste streams? Short of such changes, there would appear to be ongoing battles ahead with fossil-based plastics industrialization wherever it ventures.

For additional environmental stories and history on the oil and chemical industries, see the “Environmental History” topics page at this website. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing, and continued publication of this website. Thank You. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 26 November 2019

Last Update: 31 October 2022

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Petrochem Peril: Shell Cracker History,”

PopHistoryDig.com, November 26, 2019.

____________________________________

Books at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Oliver Morrison, “Peduto Speaks Out Publicly for the First Time Against a Petrochemical Expansion in Western Pennsylvania.” Public Source.org, October 30, 2019.

Don Hopey, “Peduto: Fossil Fuel Industries Will Take Toll on Pittsburgh Region,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 31, 2019.

Tracy Certo, “‘I Oppose Any Additional Petrochemical Companies…’; Here’s What Mayor Peduto Said at the Climate Action Summit,” NextPittsburgh.com, October 31, 2019.

Rick Mullin, “Pittsburgh’s Mayor Denounces Petrochemical Development in Western Pennsylvania; Industry Critics Applaud a Stand That Expands Bill Peduto’s Commitment to a Green Economy Beyond the City Limits,” Chemical & Engineering News, November 1, 2019.

Tracy Certo, “Under Fire, Peduto Says: ‘We Have to Evaluate Whether We Want to Become Chemical Valley’,” NextPittsburgh .com, November 4, 2019.

Don Hopey, “To Crack or Not to Crack: Peduto Fires Salvo in Regional Climate Change Battle,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 9, 2019, p. A-1.

Salena Zito. “Labor Sides With Big Oil in a Feud With Pittsburgh’s Mayor; The Dustup Is a Microcosm of Democrats’ Difficulty With Blue-Collar Voters, Especially in Pennsyl-vania,” Wall Street Journal, November 7, 2019.

Oliver Morrison, “Shunned and Praised: Peduto Reflects on His ‘In the Moment’ Remarks Against Petrochemical Expansion; The Mayor’s Stance Led to a Rare Public Disagreement with the County Executive and Framed Two Visions for the Region’s Future,” PublicSource.org, November 11, 2019.

Michelle Nacca-Rati-Chapkis, Executive Director,Women for a Healthy Environment East Liberty, “Region Should Promote Public Health, Clean Air,” Letter to the Editor, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 17, 2019, p. E-2.

David Templeton, “Childhood Cancer Concerns Prompt Meeting with Governor; Families, Groups Ask for Shale Gas Investigation,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Nov. 19, 2019, p. B-1.

Patrick J. Pagano, Co-Founder, Protect Franklin Park, “Citizens Concerned Over Fracking in Community.” Letter to the Editor, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 20, 2019, p. A-10.

“What’s An Ethane Cracker?,” StateImpact .NPR.org.

Teake Zuidema, “Have Environmentalists Lost Their Battle to Thwart the Petrochemical Industry in Southwest PA?,” PublicSource.org, February 25, 2019.

Michael Corkery, “A Giant Factory Rises to Make a Product Filling Up the World: Plastic,” New York Times, August 12, 2019.

Chris Potter/WESA, “At Rally-Like Visit to Monaca, Trump Takes Credit for Shell Plant, Touts Economic Record,” StateImpact.NPR .org, August 13, 2019.

Ryan Deto, “New Paper Details How Pittsburgh Is No Longer a Post-Industrial City,” pghCityPaper.com, November 14, 2019.

Nick Cunningham, “A Fracking-Driven Industrial Boom Renews Pollution Concerns in Pittsburgh,” e360.Yale.edu, March 21, 2019.

“Steve White Interview, Inside Climate News,” YouTube.com, posted, February 25, 2019.

Sharon Kelly, “Why Plans to Turn America’s Rust Belt into a New Plastics Belt Are Bad News for the Climate,” DeSmogBlog.com, October 28, 2018.

Terrie Baumgardner, “Your Health Vs. Cracker Plant Jobs; Consider the Full Impact of the Massive Shell Operation in Beaver County,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 6, 2017.

Paul J. Gough, “Falcon Pipeline Construction to Begin, End next Year,” Pittsburgh Business Times, June 19, 2018.

Kirk Jalbert, “Shell Pipeline: Not Quite the ‘Good Neighbor’,” FracTracker Alliance, April 2, 2018.

Matt Kelso, “Pennsylvania Pipelines and Pollution Events,” FracTracker Alliance, July 27, 2018.

Ryan Deto, “Natural-Gas Proponents and Renewable-Energy Advocates Disagree on Fracking’s Potential to Grow Jobs in Pittsburgh; ‘How Are We Going to Bring [Amazon] into Western Pa, Where the Trajectory Is Defined by Natural Gas? That Is Where There Is a Disconnect’,” pghCityPaper .com, April 18, 2018.

Stephen Huba, “Ohio Regulatory Approvals Bring Second ‘Cracker’ Plant in Region Closer to Reality,” TribLive.com, January 7, 2019.

J.D. Prose, “Shell Falcon Ethane Pipeline Work Moving Along,” TimesOnline.com, June 24, 2019.

FracTracker Alliance, “Falcon Pipeline Moves Forward Despite Unresolved Concerns,” FracTracker.org, December 21, 2018.

Erica Jackson, “The Falcon Public Monitoring Project,” FracTracker.org, May 8, 2019.

“Revolution Pipeline Near Pittsburgh Ex-plodes; Home & Barn Destroyed,” Marcellus Drilling.com, September 11, 2018.

Katie Colaneri, “Chevron Blocked Access to DEP After Fatal Well Fire in Southwest PA,” StateImpact.NPR.org, April 9, 2014.

Stephanie Ritenbaugh, “Chevron Fined $940,000 for Fatal Gas Well Fire in Greene County,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 1, 2015.

Reuters, “Exxon’s XTO Caps Leaking Ohio Gas Well, 20 Days After Blowout,” March 7, 2018.

Stephen Leahy, “Fracking Boom Tied to Methane Spike in Earth’s Atmosphere; the Chemical Signature of Methane Released from Fracking Is Found in the Atmosphere, Pointing to Shale Gas Operations as the Culprit,” NationalGeographic.org, August 15, 2019.

Rebecca Falconer, “Satellite Uncovers Ohio Gas Well Blowout’s Massive Methane Leak,” Axios.com, December 2019.

Multiple Authors, “Satellite Observations Reveal Extreme Methane Leakage from a Natural Gas Well Blowout,” PNAS.org, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, December 16, 2019.

Amanda Doyle, “Explosion at Natural Gas Facility Injures Four,” TheChemicalEngineer .com, December 14, 2018.

Anya Litvak, “Four Injured, One Critically, in Fire at MarkWest Processing Plant in Washington County,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 14, 2018.

Don Hopey, “Natural Gas Processor to Pay Nearly $7m to Settle Pollution Violations,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 2, 2018.

“Mariner East: A Pipeline Project Plagued by Mishaps and Delays,” StateImpact.NPR.org.

Claire Sasko, “Should We Be Afraid of the Mariner East Pipeline? The Ongoing Battle over the Project Is Taking Place in the Backyards of Chester and Delaware County Residents, Who Live in Fear of a Catastrophe,” PhillyMag.com, July 6, 2019.

Andrew Maykuth, “Mariner East Pipeline Hit with $319,000 in Fines for Pennsylvania Violations,” Philadelphia Inquirer/Inquirer .com, August 30, 2019.

Energy Transfer, “Marcus Hook Industrial Complex,” MarinerPipelineFacts.com.

Daniel Markind, “Mariner East 2’s Troubles Underscore Need For New Industry Approaches Toward Northeastern Popula-tion,” Forbes.com, October 2, 2019.

Diana Nelson Jones, “For Those Living Along Sunoco’s Mariner East 2 Pipeline, a Human Chain of Frustration,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 7, 2018.

Marc Levy, Associated Press, “FBI Eyes How Pennsylvania Approved Mariner East Pipeline Project, Sources Say,” Post-Gazette.com, November 12, 2019.

“Ethane Cracking in the Upper Ohio Valley: Potential Impacts, Regulatory Requirements, and Opportunities for Public Engagement,” Environmental Law Institute, January 2018.

Mark Fischetti, “Fracking Would Emit Large Quantities of Greenhouse Gases; ‘Fugitive Methane’ Released During Shale Gas Drilling Could Accelerate Climate Change,” Scientific American, January 20, 2012.

Reid Frazier, “Could Shell’s Ethane Cracker Erase Recent Gains in Air Quality?,” AlleghenyFront.org, September 9, 2016.

Jeffery Fraser, “Petrochemical Alley: Shale Gas Build-Out Raises Prospects for Jobs and Air Pollution,” Pittsburgh Quarterly, 2017 Fall.

Reid Frazier, “Enviro Group Names Names in New Anti-Pollution Campaign,” Allegheny Front.org, October 3, 2017.

Paul Van Osdol, “Investigation: Cracker Plant Will Bring Jobs, Pollution; Some Medical Experts Said Breathing Will Be Much Harder Once Plant Is up and Running,” WTAE.com, May 9, 2019.

Paul Van Osdol, “EPA Chief Vows Cracker Plant Will Be Clean; President Trump to Visit Shell Facility Under Construction in Beaver County,” WTAE.com, August 12, 2019.

Marlene Motyka, Andrew Slaughter, Carolyn Amon, “Global Renewable Energy Trends,” Deloitte Insights/Deloitte.com, 13 September 2018.

P. Bérest1and B. Brouard, “Safety of Salt Caverns Used for Underground Storage: Blow Out; Mechanical Instability; Seepage; Cavern Abandonment,” Oil & Gas Science and Technology – Rev. IFP, Vol. 58 (2003), No. 3, pp. 361-384.

Clay Jones, Terrel Laroche,and Cheryl Ginyard-Jones, “U.S. Ethane Crackers and Ethylene Derivative; Economics Behind Monetizing Cost-Advantaged U.S. Ethane Reserves, Part 2″, Honfleur LLC, June 2016.

U.S. Department of Energy, Report to Congress, “Ethane Storage and Distribution Hub in the United States,” November 2018.

“US DOE Details Marcellus-Utica Ethane, Petrochemical Options,” Oil & Gas Journal, March 2019, pp. 49-50.

“DEP Staffers Called to Testify Before Grand Jury; Criminal Probe Involves the Shale Gas Industry,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 22, 2019, p.A-1.

__________________________